Abstract

This paper presents a heading alignment procedure for drone navigation employing a single hover GNSS antenna combined with low-grade MEMs-IMU sensors. The design was motivated by the need for a drone-mounted differential interferometric SAR (DinSAR) application. Still, the methodology proposed here applies to any Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) application that requires high-precision navigation data for short-flight missions utilizing cost-effective MEMs sensors. The method proposed here involves a Bayesian parameter estimation based on a simultaneous cumulative Mahalanobis metric applied to the innovation process of Kalman-like filters, which are identical except for the initial heading guess. The procedure is then generalized to multidimensional parameters, thus called parametric alignment, referring to the fact that the strategy applies to alignment problems regarding some parameters, such as the heading initial value. The motivation for the multidimensional extension in the scenario is also presented. The method is highly applicable for cases where gyro-compassing is not available. It employs the most straightforward optimization techniques that can be implemented using a real-time parallelism scheme. Experimental results obtained from a real UAV mission demonstrate that the proposed method can provide initial heading alignment when the heading is not directly observable during takeoff, while numerical simulations are used to illustrate the extension to the multidimensional case.

1. Introduction

Navigation is a core component of drone guidance, control, and navigation (GNC) systems, which themselves are essential subsystems of drones. To function effectively, orientation and navigation must adhere to specific performance standards, which are often focused on precision, accuracy, integrity, availability, and continuity. These last four parameters, the required navigation performance criteria (RNP), form the basis for navigation specifications.

Our paper’s scenario is a planned drone flight spanning some kilometers subject to eventual wind perturbations. The radar-borne terrain imagery requires the drone to carry three radars operating in P-, L-, and C-bands with cross-track (InSAR) and differential interferometry (DinSAR) for three distinct imagery reconstructions, with different penetration and detail grading; see [1]. The self-navigation system of any drone does not attain the required precision to retrieve the complete path evolution within less than mm in the absolute spatial position, in pitch and roll angles, and in the heading accuracies. Thus, it carries extra IMU and a GNSS receptor operating in the differential mode.

When using low-cost inertial sensors for navigation of UAVs, such as IMUs based on MEMs technology and single-antenna GNSS receivers, one faces a significant challenge: obtaining the vehicle’s true heading before taking off. In this context, the usual way to find heading orientation with satisfactory accuracy in aerial navigation of UAVs with a single GNSS antenna relies on gyro-compassing, e.g., see [2] for an account of existing forms of heading alignment.

In short, the measurements available come from the GNSS in the differential mode, providing a very accurate position, together with 3D translational accelerations and rotations supplied by an MEMs-IMU. The latter is a low-cost sensor, which suffers from degrading bias and relatively low accuracy compared to aerospace IMU standards. It cannot perform gyro-compassing, thus lacking precision to measure attitude angles by simply integrating the kinematic variables.

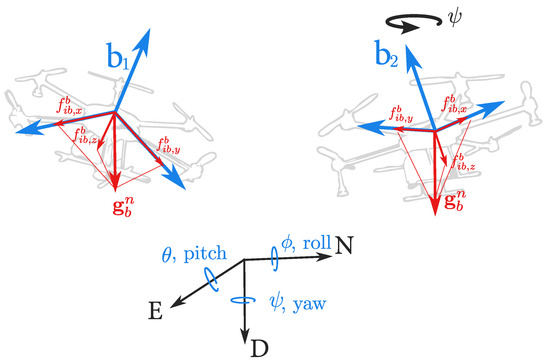

In a GNSS/INS loosely coupled integration scheme performed by a Kalman-like filtering algorithm, the pitch and roll estimates are more accurate than the heading, mainly because of their orientation relative to the gravity vector. The accelerometers in the INS module continuously measure the gravity acceleration vector, which in steady flight is orthogonal to the heading plane, providing good information on pitch and roll angles; however, it is poorly correlated with the heading angle; see Figure 1. Suppose a lever arm between the GNSS antenna and the IMU exists. In that case, it may provide some correlation information with the heading angle depending on the path profile developed by the UAV.

Figure 1.

The diagram illustrates the invariance in the projections of the gravity vector () on the body axes of a UAV after a change in the initial heading (yaw rotation). Thus, even before the flight, the readings would be the same for frames and , making it impossible to determine the initial heading of the UAV.

This paper further develops the heading determination ideas outlined in [3] that suit the post-processed flow. The expansion of this technique is two-fold. First, we adapt to the real-time scenario of navigation based on the loosely coupled GNSS/INS integration problem, and then it is adapted to the multiparameter alignment problem. The filter processing could take a parallel form in real-time, seeking the heading estimate while adopting a rougher prior heading guess until the convergence.

The heading alignment technique can be extended to multiple parameter alignment in a multivariable extension of the previous method to tackle the simultaneous adjustments, with interest to the navigation problem. For example, it applies to an accurate lever arm or body-to-IMU rotation determination in a UAV platform. Also, considering the improvement in IMU bias stability in up-to-date MEMs devices, the bias can be taken for granted as fixed during short drone flights, and the multivariable alignment technique applies to their determination as well. Although more demanding and requiring more steps, the multivariable method leads to better values than the starting values, since, under certain conditions, it produces a monotone decreasing sequence in terms of an estimation error. With that, the number of steps can be chosen as a compromise between the accuracy and effort required for the drone application in mind.

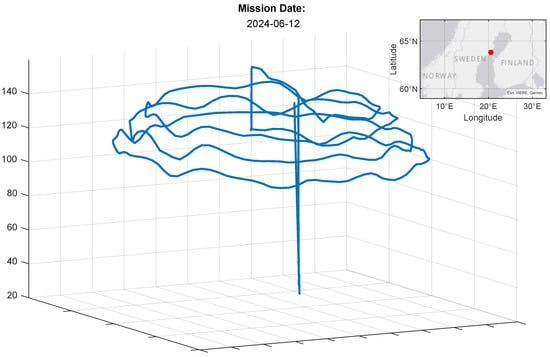

This paper reads as follows. Section 2 briefly introduces the elements of an inertial navigation system, the dynamics, and the GNSS measurement models. It details the preliminary alignment procedure for the pitch and roll angles. It presents the extended Kalman filter on Lie groups. It describes how the RMS mean value of the innovation process can qualify parameter adjustments, namely, the guesses of the initial heading. Section 2 ends with a brief presentation of the quadratic fitting optimization technique, which is our ultimate tool. Section 3 develops the heading alignment method as a Bayesian parametric estimation in post-processed and real-time tailored for UAV navigation. This section also includes results with experimental data, see Figure 2, from a study of an actual UAV platform used to evaluate the log-likelihood curve profile and the convergence process. Section 4 develops the multidimensional extension using quadratic fit optimization adapted to the multidimensional problem. It produces a monotone decreasing sequence that assures a better parameter vector adjustment. Considering the cost of multiple evaluations, some algorithm ideas are devised. Concluding remarks appear in Section 5.

Figure 2.

The flight profile of a mission conducted in June 2024 in Sweden at the indicated map location. Two ZED-F9P GNSS receivers and an ADIS 16945 inertial system were used.

3. Heading Alignment for UAVs

The heading alignment procedure applies differently depending on whether the application is in real-time or post-mission. The more straightforward case is the post-mission one, which will be studied next.

3.1. Post-Mission Heading Alignment

In the post-mission scenario, we seek a reliable initialization of the heading angle () of a UAV platform using the flight track of the drone. Moreover, we are interested in using low-cost MEMs sensors without a gyro-compass capability.

For this purpose, we adjust the Bayesian parametric estimation scheme described in ([19] [cap.16]) to the present problem. The method applies when all flight data are collected and represented generically by , and it evaluates the posterior distribution . Once the posterior distribution is obtained, the strategy is to find the most likely value for the initial heading according to , which results in the Maximum a Posteriori (MAP) estimator for the initial heading.

To start, note that from Bayes’ theorem, one has

is some prior distribution related to a (rough) heading orientation adopted before takeoff. For simplicity, consider (in degrees or radians) and as a prior for the heading initial orientation. Moreover, note that can be factorized in the form

In view of the two statistical moments furnished by the KF, we assume that the marginal measurement distribution along the path , is well approximated by a Gaussian distribution of form

where and come from the filtering solution in Equation (6) associated with some fixed value. Hence, the most likely value for the initial heading can be found by solving .

Let . Then,

with and is the filter innovation process at time k. Note that for each value of , Equation (12) provides the respective log-likelihood up to a constant such as . Thus, for a sufficient number of evaluations of different values for , one can build the distribution using the filtering solution.

Now, we assume that the noise possesses a smooth (continuous of class) unimodal distribution. The implication is that the likelihood in Equation (12) has a global minimum, say , and according to the Taylor approximation, where H is the Hessian of evaluated at the minimum . In the notation above, for a multivariable parameter , the first term in the rhs is the quadratic form .

This is a scenario where quadratic fitting can be applied [18]; when is scalar, such as the initial heading, it suffices to evaluate in three distinct points, and one can obtain the approximated log-likelihood function and estimate its minimum using the quadratic fit in Section 2.4. By applying it successively to the three best points, the optimal value can be reached.

In the multivariable case, the parameter belongs to an n-dimensional Euclidean space and this paper extends the quadratic fit to search in such a space; see Section 4.2. Of course, other optimization methods using derivatives or not could be used. The focus on the quadratic fit and its generalization regards the simplicity of the optimization procedure since each evaluation of the cost requires the observation during a period of length N of the filter result, namely the innovation process and the filter covariances for each parameter value . Computational effort and time to converge should be of regard.

Therefore, this work proposes a heading alignment scheme that is well suited for drone navigation using low-cost MEMs-IMU sensors. They consist of three independent D-LIE-EKFs, each with a different initial heading value . After running these three filters, three samples from the log-likelihood are obtained. After that, a unidimensional quadratic curve is fitted to the sample pairs , , and a minimizer point is determined; see Equation (7). Such a new value may attain precision and suffice to halt the procedure. The quadratic fit approximation improves as long as the three chosen points become nearer to the minimum; further iterations are a matter of the project’s required accuracy since the quest to attain the optimal requires producing a minimizing sequence as described in Section 2.4.

3.2. Real-Time Heading Alignment

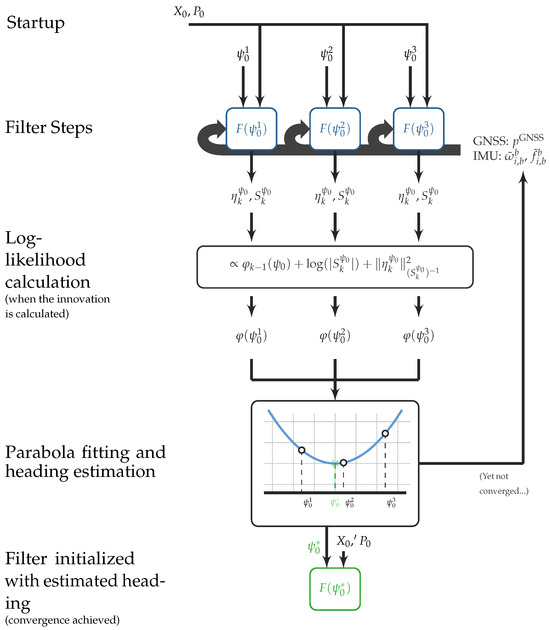

In real-time operations, we devise a procedure to provide initial heading estimates during the actual flight of the drone, allowing an initial time window for a satisfactory estimation. During the calibration window, the following steps are involved (see also Figure 3):

Figure 3.

Illustrative diagram showing the steps involved in obtaining the heading estimate via MAP of in a real-time application of a drone navigation system.

- 1.

- Initialize a set of three filters , each parameterized by an initial heading otherwise equal initial conditions. The central value of would carry a rough estimate of the initial heading;

- 2.

- Acquire streaming data from the GNSS and the IMU. Note that these are obtained at different sampling rates;

- 3.

- Feed the independent filters with the measurements, executing the prediction step, Equation (6a), at the accelerometer/gyroscope sampling rate, and the update step, Equation (6d), at the GNSS sampling rate;

- 4.

- During update step, compute for each filter the k-th term of the sum in Equation (12).

- 5.

- Using the three values of , parameterize a parabola and find its minimum, representing an estimate of the initial heading .

- 6.

- Finally, create a new filter initialized with the best initial heading estimate and fed the data collected so far.

After accumulating sufficient values, that is, N in Equation (12) is large enough, the estimate should converge to the initial heading that maximizes the posterior probability, thus, performing an MAP estimation of . A stopping criterion must be adopted to assess convergence, and due to the reduced time to converge, the initial estimation window is small and coincides with initial drone maneuvers.

During the estimation window, one of the three filters considered produces the trajectory estimation. Considering the filter processing time, the trajectory estimation provided by the correct filter should be able to catch up to the most recent data in the stream.

3.3. Heading Alignment Performance Evaluation

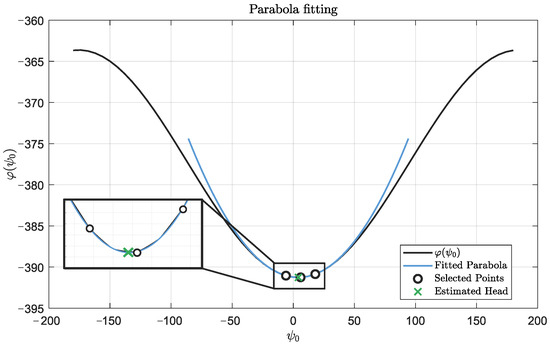

Figure 4 shows an example of a single-step filter-based heading alignment optimization proposed in this work applied to a real navigation dataset collected during an actual flight test of a UAV, specifically, the one depicted in Figure 2. It shows the results after convergence during an actual flight mission. Three choices of initial heading angles are , and guessed from a rough estimate given by a simple off-the-shelf compass.

Figure 4.

Quadratic approximation (blue curve) obtained by sampling three distinct initial heading values. The black curve is the log-likelihood function obtained for the real data flight in Figure 2. Note the remarkable precise sinusoidal profile. The minimum point of the quadratic approximation (in green) is taken as the estimate for the initial heading.

The actual log-likelihood curve for is shown from calculations on a fine angle grid, using 60 distinct initial heading values ranging from to . Near the minimum, a quadratic fit passes through points , and to estimate the precise value. The best initial heading in this example is . Note that the quadratic approximation is close to the exact curve, and both minima nearly coincide.

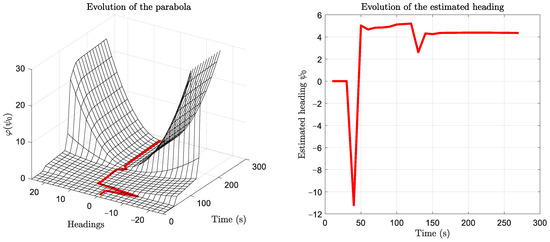

The above example corresponds to the post-mission heading alignment operation scenario. In a second experiment, we evaluate the convergence of the method using the same drone flight trajectory now devoted to real-time operation. The result is summarized in Figure 5, depicting how the initial heading value and the quadratic approximation evolve over time.

Figure 5.

Two perspectives following the evolution of heading estimation: the first is a three-dimensional mesh representation of the parabolas fitted over time; the second is a view of the vs. time plane, illustrating the evolution of the estimated heading values (the parabola’s minimum point).

In an initial stretch, the first 40 s of the trajectory, the filter has not yet performed an update step in flight (only ZVU updates), and therefore, no innovation calculation or heading estimation occurs. From the end of this interval, the in-flight update step execution begins, and the heading starts to be estimated.

The method does not provide an accurate estimate in the second time stretch, roughly between 100 and 130 s. The estimate fluctuates greatly due to the low curvature of the parabola associated with large distribution variances.

Finally, after about 130 s (90 s from the start of the flight), the initial heading estimate converges to a value of . At this point, the curvature of the parabola is significantly higher.

4. Extension to Multidimensional Alignments

Here, we discuss multidimensional alignments in analogy with the scalar case. The idea is to extend the problem studied in Section 3 where we wish to evaluate the performance of a filter regarding a multidimensional parameter .

The motivation relies on dealing with the accelerometer and gyroscope bias. Also, in some situations, the preliminary alignment of pitch and roll described in Section 2.2 cannot be applied or leads to poor results. In some cases, other parameters are necessary before taking off for a UAV platform, such as the IMU-to-Body rotation matrix or the lever arm to the GNSS antenna. Although the scalar method applied to the heading assessment in Section 3 could be applied sequentially by component, a multivariate method that can deal with all parameters simultaneously is desirable for faster determination. We propose extending the scalar method to deal with such a scenario.

4.1. Multidimensional Alignment

Suppose that we are dealing with a multidimensional alignment problem of a UAV platform where a parameter is constant but unknown during the flight. Following the same approach as described before, we define the posterior distribution of these parameters as

with prior . Moreover, note that can be factorized in the form

As before, employing the two moments estimated by the KF, we assume that the marginal measurement distribution along the path , is well approximated by a Gaussian distribution of the form

where and come from the filtering solution in Equation (6) associated with some fixed m-dimensional value. Hence, the most likely value for the parameter can be found by solving where . Then,

with and is the filter innovation process at time k. Note that for each value of , Equation (15) provides the respective log-likelihood up to a constant such as . Thus, by the account of the filtering innovation process and correlation matrices, with successive evaluations of parameter , associated with decreasing values of , one can reach the minimum of and obtain its unique minimizing argument .

4.2. Quadratic Fit: Multidimensional Extension

Many optimization methods could apply to the multidimensional MAP problem by minimizing in Equation (15). Alternatively, the equivalent MMS estimator can be evaluated by sampling the approximate conditional distribution . However, a general feature of the outlined scenarios is that the evaluation until convergence of Equation (15) (or even Equation (12)) at each (or ) is relatively expensive due to the filter parameter calculations along N stages, which can be relatively large. Furthermore, attaining the optimal will be costly and perhaps unnecessarily time-consuming, and a procedure that guarantees the monotonicity of the cost, in the sense that whenever , is highly desirable.

Considering these constraints, we propose an optimization procedure that applies to the multidimensional case, relying on the simplicity of the quadratic fitting concerning the number of evaluations and the easiness of calculus. First, we brought the linear algebra tools to bear to allow the quadratic fit method to be applied to a multidimensional function using a planar bisection passing through three points.

The problem we wish to unravel is as follows: Given and the corresponding values , find the plane in containing these points. If , and are the corresponding points in , the plane containing these points can be represented as , for some , where . Applying Givens rotations successively, one obtains a rotation matrix T such that for any ,

Applying such transformation to , and , we obtain and

and three coordinate pairs as , and . Now, by setting the correspondence and in Equation (7), a minimizing value and the corresponding quadratic value , provided that Equation (8) is satisfied. From the fact that T is a rotation matrix, thus it is a length-preserving transformation, and the final result in the original coordinate is obtained by

The first component could be the resulting quadratic value if the indicated constant is determined, but it is of no avail in the calculus here.

4.3. The Minimizing Algorithm

A strategy to apply the multidimensional quadratic fit extension in Section 4.2 must be developed. The basic assumption is that the original operating point, say , is near the minimum; therefore, the search is local. Also, finding the minimum is not necessarily the goal. One may be satisfied with improving the operating point since seeking the minimum might be time-consuming, computationally expensive, or other practical issues may prevent the quest. Whichever is the reason, the idea is to produce an algorithm to find new operating points while monotonically decreasing costs.

The first notion is to investigate two neighboring points around and find the corresponding values , apart from the present operating point ; this represents the most economic spatial covering of the neighborhood of . To choose directions and , we can borrow from curvature integration methods and use the idea of sigma points around . Given a unitary norm vector (the vector notation is used here to facilitate understanding) , create a set of sigma points centered at , such as the construction of the set of points is represented by the operator , which applied to produces a set of -valued vectors,

containing each combination of rotations component-wise over . That is, for some unitary , each has the form with , together with each of the possible distinct signal combinations from . Evaluations of the function f on such a grid centered at some are indicated by

The scalar value modulates the hypervolume of the sigma points covering. It relates to the uncertainty of the distance between and the unknown optimal value . It should be chosen in a way to satisfy preferably, where is the convex hull set. Algorithm 1 proceeds with the complete construction and evaluation of the sigma points as the departing idea just described, performing an exhaustive search using as a central point at each performed quadratic fit.

| Algorithm 1 A complete step of sigma point evaluations |

Require:

|

The proposed Algorithm 1 is conceptually interesting. Still, it is clearly inefficient since a new minimum, say is found along one direction at each three-point evaluation, and point can play the role of a new central point more efficiently than in Algorithm 1. Since the one-step fit just described produced a monotone decreasing variation, namely , a variation of Algorithm 1 can be devised to reduce the number of evaluations to attain a better operating point at each step.

Algorithm 2 presents a form that speeds up Algorithm 1 by centering the sigma points at the minimum value at each quadratic fitting step. It again involves a direction given by a unitary together with the corresponding “sigma points directions” constellation, , as follows. Given an operation point and a direction , at each new step, it employs two sigma points symmetrically displaced concerning , say , thus requiring only two new evaluations. Next, the constellation is re-centered at the newly found minimum, and a new direction is explored, distinct from any of the previously explored.

Note that the total number of sigma points directions are exhausted after iterations (i.e., in Algorithm 2), and the choice of directions should restart anew. Moreover, with an eye to parsimony, the number of sigma points can be further reduced for the purpose here. It seems enough to explore unitary vectors in n orthogonal directions in a n-dimensional parameter space, and if the whole set of directions is examined, namely in Algorithm 2. Lastly, the dispersion parameter in Algorithm 1 is substituted by a sequence , to express the decreasing distance to the optimal, if one can avail.

| Algorithm 2 A stepwise decreasing algorithm |

Require:

Ensure:

If is not an optimal parameter,

|

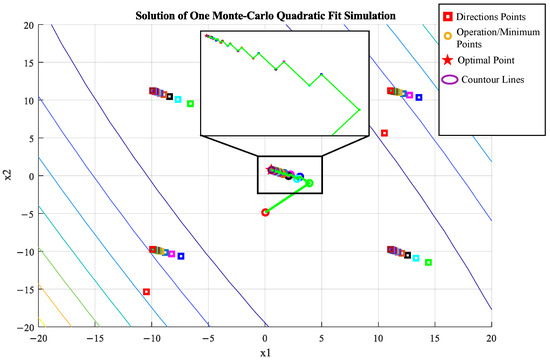

To illustrate the operation of Algorithm 2, a Monte Carlo simulation was performed, in which the following elements at each sample were randomly generated: the optimal parameter value and a positive definite matrix such that the cost is .

The matrix M is defined by a set of non-negative eigenvalues, , in which half of the eigenvalues range between and 10, and half between 10 and 160. Another support random symmetric matrix provides the orthogonal eigenvectors. The reason for generating eigenvalues with different intervals is to include scenarios where the quadratic form defining f is ill-conditioned. The initial operating point is also randomly generated.

The vector is chosen as one of the coordinate directions and . As in Algorithm 2, once a minimum is computed, the operating point is re-centered, and the next orthogonal direction is adopted to the minimizing algorithm. Table 1 shows the average relative gain from the initial cost produced by some number of iterations of Algorithm 2. Figure 6 shows convergence towards the minimum in an ill-conditioned case.

Table 1.

Average relative gain evaluation, % obtained through 500 Monte Carlo evaluations.

Figure 6.

Path convergence of Algorithm 2 in a ill-conditioned problem in two dimensions.

Table 1 shows that the minimization method for the 2D case achieves, on average, a relative gain above 99% in 50 iterations, whereas the 6D case requires twice as many iterations to reach the same percentage gain. As expected, this is mainly due to the dimensional number, as a larger number of directions must be assessed ( in 6D against 2 directions in 2D), leading to an extended convergence effort to reach the optimal.

Figure 6 depicts the convergence path in an ill-conditioned problem, exhibiting a long zigzag pattern. The minimization process is expected to converge much faster when the Hessian matrix of an actual cost f near the optimal provides a well-conditioned positive quadratic form.

5. Conclusions

This paper develops a technique to improve heading alignment applied to the GNSS/INS integration scenario tailored for drone navigation problems using low-cost MEMs-IMU sensors. It also accounts for multidimensional parameter alignment, resulting in better accuracy of the overall navigation solution for a UAV platform.

The data presented concerning heading alignment come from actual operational flights in the post-processed or in-mission flight modes. Synthetic data are used in this paper to illustrate the extension to the multivariable alignment, which is mathematically sound but still in progress.

It develops a parameter estimation scheme called parameter alignment, which differs from traditional estimation methods. The name choice is inspired by the initial concept of “heading alignment”, referred to as “parametric alignment” when generalized to any parameter. It relies at any time on three identical stochastic filters, except for some initial parameter (or parameter vector). Bayesian analysis yields the metric in Equation (12), which is a qualifying measure of each filter made up by the innovation process and the covariance matrix sequences produced by the EKF-Lie filters. The unidimensional quadratic fit applies straightforwardly to these measures, pointing out the optimal value. This work also extends to the multidimensional case, in which the different optimization methods could apply. In particular, we propose an optimization procedure based on the quadratic fit that improves the parameter alignment value at each step and is well suited to the scenario since it calculates the qualifying measure sparingly. Numeric experiments using synthetic data demonstrate the proposed method’s applicability to finding the initial heading for a drone navigation system. In addition, using the actual dataset from UAV missions, we show that better performance can be achieved in real applications of drone navigation where the IMU is incapable of gyro-compassing. The method proposed in this work is a reasonable alternative for low-cost drone navigation systems. As far as the authors know, it originates an approach to the initial heading alignment problem that is well suited for the navigation of UAV platforms.

Author Contributions

Investigation, J.F.C. and J.A.M.V.; Supervision, M.R.F. and J.B.R.d.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data are the propriety of Radaz SA, but access to them can be analyzed at request.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the Radaz Indústria e Comércio de Produtos Eletrônicos S.A. for supporting this work.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Jitesh A. M. Vassaram is employed by the company Radaz Indústria e Comércio de Produtos Eletrônicos S.A. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DinSAR | Differential Interferometry Synthetic Aperture Radar |

| MEMs | Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems |

| PVA | Position, Velocity, and Attitude |

| RTK | Real-Time Kinematic |

| KF | Kalman Filter |

| EKF | Extended KF |

| EKF-Lie | EKF on Lie groups |

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Unit |

| INS | Inertial Navigation System |

| GNSS | Global Navigation Satellite System |

| MAP | Maximum a Posteriori |

| MMS | Minimum Mean Square |

References

- Moreira, L.; Castro, F.; Góes, J.A.; Bins, L.; Teruel, B.; Fracarolli, J.; Castro, V.; Alcântara, M.; Oré, G.; Luebeck, D.; et al. A Drone-borne Multiband DInSAR: Results and Applications. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE RadarConf, Boston, MA, USA, 22–26 April 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gade, K. The Seven Ways to Find Heading. J. Navig. 2016, 69, 955–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, M.R.; Magalhães, G.M.; Zúñiga, Y.R.C.; do Val, J.B.R. GNSS/MEMS-INS Integration for Drone Navigation Using EKF on Lie Groups. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2023, 59, 7395–7408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, P.D. Principles of GNSS, Inertial, and Multisensor Integrated Navigation Systems; Artech House: Boston, MA, USA; London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Titterton, D.; Weston, J. Strapdown Inertial Navigation Technology, 2nd ed.; The Institution of Electrical Engineers: Stevenage, UK; Reston, VA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, R.M. Applied Mathematics in Integrated Navigation Systems, 2nd ed.; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Inc.: Reston, VA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Goel, A.; Aseem, S.; Islam, U.L.; Ansari, A.; Kouba, O.; Bernstein, D.S. An Introduction to Inertial Navigation From the Perspective of State Estimation. IEEE Control Syst. Mag. 2021, 45, 104–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, G.A.; Ariffin, N.H.; Ab Aziz, N.; Mukhtar, M.H.H.; Arsad, N. True north measurement: A comprehensive review of Carouseling and Maytagging methods of gyrocompassing. Measurement 2024, 226, 114121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prikhodko, I.P.; Zotov, S.A.; Trusov, A.A.; Shkel, A.M. What is MEMS gyrocompassing? Comparative analysis of maytagging and carouseling. J. Microelectromech. Syst. 2013, 22, 1257–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Shalom, Y.; Li, X.R.; Kirubarajan, T. Estimation with Applications to Tracking and Navigation; Wiley-Interscience: New York, NY, USA, 2001; p. 584. [Google Scholar]

- Blackman, S.; Popoli, R. Design and Analysis of Modern Tracking Systems; Artech House Publishers: Boston, MA, USA; London, UK, 1999; p. 1230. [Google Scholar]

- Streit, R.; Angle, R.B.; Efe, M. Analytic Combinatorics for Multiple Object Tracking; Springer International Publishing AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Blom, H.; Bar-Shalom, Y. The interacting multiple model algorithm for systems with Markovian switching coefficients. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 1988, 33, 780–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ristic, B.; Arulampalam, S.; Gordon, N. Beyond the Kalman Filter; Artech House Publishers: Boston, MA, USA; London, UK, 2004; p. 318. [Google Scholar]

- Chopin, N.; Papaspiliopoulos, O. An Introduction to Sequential Monte Carlo; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; p. 350. [Google Scholar]

- Bourmaud, G.; Mégret, R.; Giremus, A.; Berthoumieu, Y. Discrete extended Kalman filter on Lie groups. In Proceedings of the 21st European Signal Processing Conference (EUSIPCO 2013), Marrakech, Morocco, 9–13 September 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bourmaud, G.; Mégret, R.; Giremus, A.; Berthoumieu, Y. From Intrinsic Optimization to Iterated Extended Kalman Filtering on Lie Groups. J. Math. Imaging Vis. 2016, 55, 284–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luenberger, D.G. Introduction to Linear and Nonlinear Programming; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Särkkä, S. Bayesian Filtering and Smoothing, 2nd ed.; Number 17 in Institute of Mathematical Statistics Textbooks; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).