Abstract

UAV moving object detection focuses on identifying moving objects in images captured by UAVs, with broad applications in regional surveillance and event reconnaissance. Compared to general moving object detection scenarios, UAV videos exhibit unique characteristics, including foreground sparsity and varying target scales. The direct application of conventional background modeling or motion segmentation methods from general settings may yield suboptimal performance in UAV contexts. This paper introduces an unsupervised UAV moving object detection network. Domain-specific knowledge, including spatiotemporal consistency and foreground sparsity, is integrated into the loss function to mitigate false positives caused by motion parallax and platform movement. Multi-scale features are fully utilized to address the variability in target sizes. Furthermore, we have collected a UAV moving object detection dataset from various typical scenarios, providing a benchmark for this task. Extensive experiments conducted on both our dataset and existing benchmarks demonstrate the superiority of the proposed algorithm.

1. Introduction

UAV moving object detection leverages image processing techniques to identify moving objects within image sequences captured by UAVs. Here, a moving object is defined as any object that moves significantly differently from the background [1]. Moving object detection has broad application prospects in areas such as target detection, aerial surveillance, scene understanding, and event recognition [2].

Under moving observation platforms, the background of the scene continuously shifts with the movement of the platform, and the motion of the target may become confused with the motion of the background, presenting a significant challenge for moving object detection.

According to the Gestalt principle of common fate [3], elements moving in the same pattern tend to be perceived as a group. In moving object detection, the general approach is to distinguish the motion of the foreground (moving objects) from that of the background based on their motion patterns. A key challenge lies in selecting the appropriate model to represent these motion patterns and in distinguishing between the motion models of the foreground and background. Existing techniques commonly utilize constraints such as low-rank properties, subspaces, and Gaussian mixture models to differentiate foreground and background motion. The main principles employed in these typical algorithms include (1) the difference in motion patterns between the foreground and background, and (2) the temporal consistency of foreground motion.

Compared to conventional moving object detection scenarios (such as those with handheld cameras), UAV scenes present unique characteristics, including a variable field of view and relatively small target pixel sizes. These features introduce several distinct challenges for UAV moving object detection. (1) In UAV scenarios, the foreground is sparse (moving objects occupy only a small portion of the scene). (2) In UAV scenarios, the size of moving objects changes more frequently. Directly applying conventional methods from general settings may suffer from many false alarms. Fully leveraging this unique prior knowledge may lead to better results in UAV moving object detection.

However, current datasets for moving object detection in UAV scenarios remain scarce, and related research is limited. Most existing techniques rely on video object segmentation datasets such as DAVIS [4] or tracking datasets like Vivid [5], which primarily focus on observation platforms closer to the ground. These datasets typically feature a single, large target positioned at the center of the field of view. The lack of publicly accessible datasets specifically tailored for UAV-based moving object detection limits the development and evaluation of algorithms optimized for this domain. Furthermore, the integration of domain-specific prior knowledge remains largely unexplored in current detection technologies.

This paper presents a dataset named UAV moving object detection (UAVMD) specifically designed for the UAV moving object detection task. We then propose an unsupervised method based on optical flow for the task. The method leverages domain-specific prior knowledge, including foreground sparsity and the spatiotemporal consistency of foreground motion in UAV video, to guide a multi-scale segmentation network in detecting true moving objects. The algorithm operates without the need for complex annotations during training and demonstrates superior performance on UAV moving object detection, exhibiting strong generalization capabilities on unseen data.

The main contributions of this paper can be summarized as follows:

- We propose an unsupervised multi-scale UAV moving object detection network based on optical flow, which fully leverages prior knowledge in UAV scenarios. This architecture effectively separates the foreground from background by exploiting motion pattern disparities, enabling accurate detection of prominent moving objects in UAV videos.

- We incorporate prior knowledge of foreground sparsity and spatial consistency in UAV ground observation scenes using the Ising model into the loss function of the unsupervised network. This crucial step significantly mitigates false alarms arising from motion parallax and platform motion.

- We collected high-definition UAV-to-ground observation data using DJI drones, comprising 31,536 image frames at 1920 × 1080 resolution. We annotated 37 typical sequences, containing 3469 frames (spaced every 10 frames), with polygonal bounding boxes, providing a benchmark for the UAV moving object detection task.

- Our proposed method demonstrates superior performance on established benchmarks for general moving object detection and achieves outstanding results on the introduced UAV moving object detection dataset. Furthermore, it exhibits exceptional generalization capabilities across diverse scenarios.

2. Related Work

2.1. Moving Object Detection Methods Under Dynamic Observation Platforms

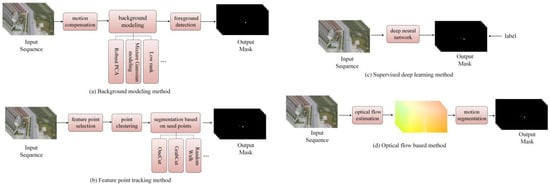

Typical moving object detection methods for dynamic observation platforms can be broadly classified into four categories based on different motion representation models, as shown in Figure 1: background modeling, feature point tracking, supervised deep learning, and optical flow-based methods.

Figure 1.

Frameworks of typical moving object detection methods under dynamic observation platforms.

- A.

- Background modeling methods

Background modeling methods create background models based on characteristics such as probability or low-rank properties in sequential images, then detect moving objects that cannot fit in the model. Several prominent approaches exist within this framework: (1) Probability distribution-based methods. Stauffer et al. [6] statistically analyze the grayscale value distribution of pixels over time, using a Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) to fit the grayscale value variations. Foreground pixels, which have a larger variance and cannot fit into the background distribution, are detected. Zivkovic [7] further utilizes an iterative equation to continuously update the GMM parameters, selecting an appropriate number of Gaussian distributions for each pixel. Lee [8] calculated an adaptive learning rate for each Gaussian model, improving the convergence efficiency of the GMM. (2) Principal Component Analysis (PCA) -based methods. The DECOLOR method [1] leverages the low-rank property of the background and uses global optimization to identify sparse foregrounds that do not fit the low-rank background matrix. To address issues such as low computational efficiency and high false alarm rates, researchers [9,10] propose improvements through subspace tracking and kinematic regularization techniques. (3) Visual background extraction methods [11]. These methods select a certain number of pixels near each site to model the background. The Euclidean distance between the pixel and the background sample values is used as a metric to classify foreground and background.

While these background modeling methods perform well under stationary camera conditions, they face challenges in dynamic camera scenarios. Motion compensation is required to eliminate the camera’s own movement. However, techniques such as homography transformations often fail to accurately compensate for complex motion, particularly in UAV views, limiting their effectiveness in these highly dynamic scenes.

- B.

- Feature point tracking methods

Feature point tracking methods first select feature points from image sequences and track their long-term motion trajectories for clustering, enabling motion segmentation of sparse feature points. Then, techniques such as Markov Random Fields are used for dense segmentation of all pixels [12,13]. The efficacy of these methods is intrinsically linked to the quality of the selected feature points. Insufficient selection can lead to missed detections, while excessive selection significantly increases computational demands, making it challenging to strike a balance between accuracy and real-time performance.

- C.

- Supervised deep learning methods

Moving object detection based on supervised deep learning leverages the powerful feature extraction capabilities of neural networks, treating the task as a classical object detection problem [14,15,16]. These networks are trained on meticulously labeled datasets of moving objects. However, analogous to appearance-based detection algorithms, this approach may not fully harness motion-specific cues. The accuracy of detection is highly susceptible to the resemblance between the test data and the training data distribution. Consequently, ensuring the network’s ability to generalize effectively across diverse and unseen scenes presents a significant challenge.

- D.

- Optical flow-based methods

Optical flow-based motion segmentation methods offer a compelling approach to identifying moving objects by leveraging the inherent motion representation embedded within video sequences. These methods initially compute optical flow fields, which quantify the motion of individual pixels across frames. Subsequently, moving objects are detected by analyzing the characteristics and patterns within these optical flow fields. Since optical flow estimation operates at the pixel level, these optical flow-based moving object detection methods can effectively exploit pixel-wise motion information, often demonstrating strong generalization capabilities. With improvements in optical flow estimation datasets and advancements in network architectures [17,18], inter-frame optical flow can now be estimated accurately in a short time. Optical flow-based motion detection has gained significant attention and holds great potential for further development.

2.2. Development of Optical Flow-Based Moving Object Detection Methods

Optical flow-based moving object detection methods can primarily be divided into two categories: sparse optical flow clustering methods and motion segmentation methods. Sparse optical flow clustering methods track selected feature points in the image using optical flow and classify them based on the distribution of feature point trajectories. In 2009, Sheikh [12] differentiated moving objects and backgrounds by utilizing 3D subspaces and the projection errors of feature point trajectories. In 2012, Kim [19] used the K-means algorithm to classify sparse optical flow points. Bugeau [20] developed a method based on feature point tracking and established a Markov random field model for dense segmentation. Sheikh [12] leveraged kernel density estimation to construct foreground and background distribution models, subsequently employing graph cuts on a MRF to achieve dense segmentation. Brox [21] introduced the Potts model, framing segmentation as a total variation problem and incorporating temporal constraints to ensure consistency across frames. Sparse optical flow clustering methods also face the challenge of initial feature point selection.

With the application of deep learning, the inference time for dense optical flow estimation has been significantly reduced, and more motion segmentation methods based on dense optical flow have been developed. Huang [22] utilized the RANSAC algorithm to estimate the homography transformation, thereby reconstructing the optical flow field. Moving objects were then differentiated by comparing this reconstructed flow field with the input optical flow. Sugimura [23] employed the Canny edge detector to identify moving object contours, selected seed points for the moving target and background inside and outside the contours, and then used the oneCut algorithm to segment moving objects in the optical flow field. In 2020, Zhang [24] proposed a method to detect moving objects that are hard to distinguish in dense optical flow by reconstructing the optical flow direction using the Poisson equation. Temporal consistency was then used to eliminate false positives. Zhang [25] then extended the robust seed point selection approach by using a random walk algorithm.

Thanks to its speed and strong feature representation capabilities, deep learning has increasingly been applied to motion segmentation tasks in recent years. For instance, ref. [26] employed convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to detect independently moving objects. This network was trained directly on annotated labels, taking optical flow maps as input. Ref. [27] introduced a novel approach utilizing slot attention to segment moving objects by analyzing the discrepancies between reconstructed and input optical flow fields. Ref. [28] explored an unsupervised learning paradigm, initializing their network with pre-trained semantic features and subsequently training it to discern motion patterns. MATNet [29] simultaneously utilizes motion and appearance features, employing an attention framework to achieve better segmentation results. FSNet [30] adopts a parallel-cross architecture, using cross-attention modules to continuously exchange useful clues between appearance and motion features. AMC-Net [31] assigns weights to appearance and motion features based on the evaluated importance. GWM [32] proposed approximating optical flow using a set of parametric models, each representing a distinct motion component. In 2022, Etienne Meunier [33] suggested that the input optical flow can be represented by a set of affine or polynomial motion models. This framework led to the development of a CNN-based segmentation network, which referred to the classic EM algorithm for unsupervised division of the input optical flow into distinct sections according to these motion models. In 2023, UST [34] argued that temporal consistency is also a crucial clue for optical flow segmentation. They designed a 3D network for motion segmentation, where the loss function combines a flow reconstruction term based on spatiotemporal motion models and a regularization term that enforces foreground mask temporal consistency. TMO [35] highlighted the issue of poor motion information quality in optical flow maps for certain scenes and proposed selectively utilizing motion clues. The framework aims to reduce reliance on motion features when the quality of the motion information is compromised.

Optical flow-based motion segmentation methods have shown significant potential for moving object detection, but we have noticed that few methods specifically incorporate domain-specific prior knowledge from the UAV scenarios.

2.3. Development of Moving Object Detection in UAV Scenarios

Murari [2] utilized a multi-level feature pyramid supervised network to detect moving objects in UAV videos. K. Berker [36] selected 14 sequences from the VIVID and UAV123 [37] tracking datasets, annotated the moving object with rectangular bounding boxes, and developed a detection algorithm based on homography compensation and differentiation for low-altitude UAV scenarios. Hazal [38] explores the use of sparse flow to enhance the real-time performance of moving object detection in low-altitude UAVs, with experiments also conducted on the VIVID and UAV123 tracking datasets. B. Kalantar [39] used trajectories of matched regional adjacency graphs for moving object detection. M. Siam [40] considered utilizing homography transformation to warp the input dense optical flow to mitigate the impact of motion parallax. J. Li [41] estimated the global background motion model using sparse optical flow, then compensated for it and performed background subtraction to detect UAVs in flight. Kimura [42] applied epipolar constraints and flow-vector bound constraints to differentiate moving objects from the background. Note that these epipolar constraints require camera intrinsic parameters, and accurate background subtraction demands prior knowledge of the target’s approximate speed. In real-world scenarios, obtaining such valuable prior knowledge can be difficult.

3. Approach

We consider using a spatiotemporal polynomial motion model [34] to classify the motion in the scene into two layers: background and true moving objects (foreground). Foreground sparsity and spatiotemporal consistency are incorporated into the loss function to constrain a 3D multi-scale U-Net network to learn and segment the true moving objects, helping to mitigate false positives caused by motion parallax and background motion.

3.1. Framework

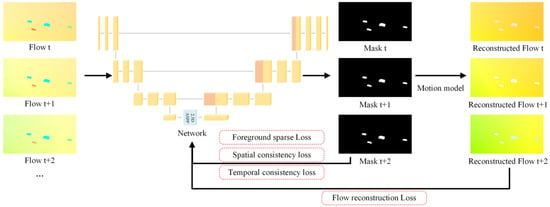

Figure 2 illustrates the framework of the proposed unsupervised UAV moving object detection algorithm. We first use a dense optical flow estimation network to compute the dense optical flow between frames in the image sequence , which is then fed into the segmentation network as input. In this paper, we use three consecutive optical flows, i.e., . The classical 3D U-Net [43] architecture is employed as the segmentation network, with a 2.5D Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling (ASPP) module added at the bottleneck to enhance the network’s ability to capture multi-scale features. The backbone is flexible and can be substituted with any other suitable segmentation network. The network partitions the input optical flow (representing the overall motion in the scene) into layers, specifically the foreground layer () and the background layer (), and outputs the probability that each site belongs to layer (foreground or background). The pseudocode is provided in Appendix A.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of the proposed method.

During the training step, after the network outputs the layer segmentation results , we aim to enforce consistency in motion patterns within each layer. To achieve this, we employ a motion model to represent the motion characteristics of each layer. This model aids in reconstructing the optical flow field, allowing for a comparison with the original input optical flow field and thus evaluating the accuracy of the layer segmentation. Following [34], we adopt a spatiotemporal parametric motion model , as shown in Equation (1), to represent the motion of each layer.

where represents the pixel motion of the pixel location at time t, with the motion parameters .

This model consists of 12 parameters, with used to constrain spatial motion variations, and to constrain temporal motion changes. We employ the L-BFGS algorithm [34,44] to compute the specific motion model parameters for both the foreground and background layers based on the network’s layer segmentation outputs. With these motion model parameters, we can reconstruct the optical flow field.

Next, by utilizing the difference between the reconstructed optical flow field and the input optical flow, along with the foreground sparsity and spatiotemporal consistency loss terms, we apply constraints to the network. This encourages the network to learn to differentiate between the foreground and background by categorizing the overall motion based on the differences in motion patterns, thereby enabling the detection of moving objects from the moving background. A detailed explanation of these loss functions will be provided in Section 3.2.

During the inference step, the layer probabilities output by the network represent the desired detection results, and no further motion model estimation phase is required.

3.2. Loss Function

The network’s loss function consists of four components: a flow reconstruction term , a spatial consistency term , a temporal consistency term , and a foreground sparsity term . The total loss is the sum of these four terms:

where , , and are the hyperparameters to balance the loss components.

3.2.1. Flow Reconstruction Loss

The flow reconstruction term is computed based on the L1 norm between the reconstructed flow field, obtained from the parameterized motion model, and the input optical flow. This term quantifies how well the motion model can represent the scene’s motion. According to reference [34], the flow reconstruction loss is given by:

where is the image grid, denotes the probability of the site at time belonging to the layer , which is the output of the motion segmentation network, is the input flow, and denotes the reconstructed flow derived from the motion model with the estimated parameter .

3.2.2. Spatial Consistency Loss

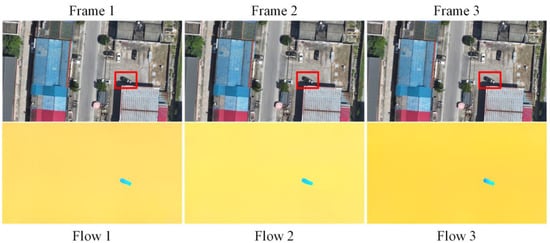

In the scenario of drone-based ground observation, the reconnaissance area in video mode is relatively small, and the target size in the image typically exceeds several tens of pixels. According to the Gestalt principle of common fate, elements of the same entity tend to exhibit similar motion patterns. The optical flow of each pixel within the same entity is spatially closely related, typically exhibiting similar motion amplitudes and directions. In the temporal dimension, with a frame rate of 24 fps, the temporal interval between frames is less than 0.05 s. The moving object’s motion is generally smooth and continuous over such a short period, without abrupt discontinuities. In the drone scenario, the moving targets can be simply modeled as rigid bodies, with no internal contraction or expansion. As shown in Figure 3, the motion of the moving target forms a cluster of prominent sites with spatiotemporal consistency in the optical flow field. That is, the mask of a moving object should exhibit strong spatiotemporal consistency.

Figure 3.

An example of UAV sequence data. The first row displays the RGB images, with moving targets highlighted by red bounding boxes, while the second row presents the corresponding visualized optical flow maps.

Additionally, the smoothness constraint of optical flow [45] implies that the optical flow between pixels in an image experiences abrupt changes only at object boundaries, which occupy a small portion of the image. Overall, the optical flow field should remain smooth. Likewise, the predicted foreground mask of the moving target should demonstrate spatial smoothness, preserving spatial consistency across neighboring pixels. Inspired by the Ising model [1,46], we introduce the following spatial consistency loss , which may help eliminate point noise and false positives.

3.2.3. Temporal Consistency Loss

As analyzed in Section 3.2.2, the motion of real moving objects is smooth, without abrupt changes in short time intervals. This implies that the segmentation results produced by the network should likewise display temporal consistency. Inspired by the work in [34], we introduce the following temporal consistency loss function:

3.2.4. Foreground Sparse Loss

In the UAV-based moving object detection scenario, target sizes are typically small, often measuring around 20 × 40 pixels or smaller. This represents a mere 1/2000th of a standard 1920 × 1080 image, resulting in a highly sparse foreground comprising only these minute targets. To effectively exploit this valuable prior knowledge, we introduce a foreground sparsity loss function. This constraint guides the network to identify genuine moving targets only when their motion demonstrably diverges from the background. By enforcing this separation of foreground and background motion models, we aim to mitigate the confounding effects of motion parallax and the UAV’s own movement. The foreground sparsity loss is defined as follows:

4. Experiments

4.1. Datasets

We utilized the DJI M3T and M3E drones to collect data for typical UAV moving objection detection scenarios. Captured scenes encompassed a variety of environments, including urban blocks, farmlands, lakesides, and country roads. The drones flew at an altitude of approximately 400 m, using focal lengths of 1X, 2X, 4X, and 7X to capture ground-based moving targets. The camera’s pitch angle included typical reconnaissance perspectives, such as 90°, 60°, and 30° downward views. Furthermore, drones operated in diverse modes, including forward reconnaissance, hovering, camera rotation, and focus tracking, to effectively capture the targets from various angles. The video image sequences were recorded at 30 fps, with a resolution of 1920 × 1080. The UAVMD dataset comprises 70 sequences totaling 31,536 images. For evaluation purposes, we annotated 37 representative short sequences, providing annotations every ten frames with polygonal bounding boxes. Figure 4 shows examples from the dataset, with annotated moving targets highlighted in red masks.

Figure 4.

Samples of our UAVMD dataset.

The UAVMD dataset encompasses a diverse range of moving object types across multiple scales, encompassing motorcycles, tricycles, passenger cars, trucks, and more. During annotation, these moving targets were labeled as foreground objects without differentiation by type. The dataset incorporates targets with varying speeds and also accounts for incomplete moving targets, such as those affected by occlusion or entering/exiting the scene. And it is publicly accessible at https://github.com/fanxuxiang/UAVMD-sets-and-related-codes (accessed on 30 December 2024).

4.2. Implementation Details

For training, we utilized 23 sequences encompassing 24,849 images from the UAVMD dataset, with sequence lengths varying from hundreds to thousands of frames. An additional 10 sequences, containing 3218 images, were reserved for validation. The input optical flow was estimated using an improved RAFT (publicly accessible at https://github.com/fanxuxiang/LKCMA (accessed on 10 February 2025)). Note that the training and validation sets are completely unannotated. Annotations are reserved exclusively for testing purposes. The balance hyperparameters for various losses were set to , , and . Data augmentation was implemented following the strategy in [34], which randomly added global motion to enhance the diversity of the dataset. The network was trained on two RTX 4090 GPUs. During training, the flows were resized to 540 × 960. The Adam optimizer [47] was used, with a learning rate set to . InstanceNorm [33] was employed to enhance stability.

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

We use both pixel-level and object-level metrics for quantitative evaluation of the UAV moving object detection task.

The pixel-level evaluation metric, Jaccard index (JI), is defined as follows:

where is the predicted foreground pixel-level mask output by the network, and is the annotated foreground mask.

The evaluation metrics at the object level are based on (Pr), (Re), and comprehensive metric F1, as shown in Equation (8). The output mask is divided into different objects based on connectivity. When the Intersection over Union (IoU) between the detected object and the ground truth annotation exceeds a threshold , it is considered a correct detection. In this paper, is set to 0.5.

where TP, FP, and FN represent the numbers of true positives, false positives, and false negatives, respectively.

4.4. Quantitative Results

To evaluate the effectiveness of the methods in UAV moving object detection, quantitative evaluations were conducted on the UAVDT test dataset. Table 1 presents a comparison between the proposed method and several classical methods, including the background modeling method DECOLOR [1], the video object segmentation method TMO [35], the unsupervised motion segmentation method EM [33], and UST [34]. The unsupervised methods were trained using the same methodology on the UAVDT data. Since only the test set is annotated, for supervised methods that require labeled data during training, we used the pre-trained weights provided in the original papers for comparison. The results demonstrate that the proposed method outperformed all other methods in terms of pixel-level JI, object-level precision, and F1 scores. Compared to the recently developed motion segmentation method UST, our method achieved a 35% improvement in JI, a 14% increase in precision, and a 9% improvement in the overall F1 score. Due to the stricter constraints imposed on foreground sparsity and spatial consistency during implementation, the recall rate of our algorithm did not show a significant improvement.

Table 1.

Quantitative evaluation results on the UAVMD dataset. Due to memory and inference time limitations, the input image sequences were downsampled by a factor of 2 for DECOLOR method. The other methods were tested at the original 1080 × 1920 resolution.

Table 2 presents the test results on the BMS [48] dataset, a general moving object detection benchmark. Compared to our UAVDT dataset, the BMS dataset features larger target sizes, with most targets located near the center of the field of view. Since the annotations in the BMS dataset are not at the object level, evaluation was performed using pixel-level F1 scores. Note that the supervised method TMO’s training data align closely with the BMS dataset, and the BMS method itself underwent fine-tuned parameter selection specifically for the BMS dataset. Furthermore, our proposed method was not trained or validated on the BMS dataset. Notwithstanding these differences, our method achieved F1 scores comparable to those of the other methods, demonstrating strong cross-dataset generalization capabilities.

Table 2.

Quantitative evaluation results on the BMS dataset.

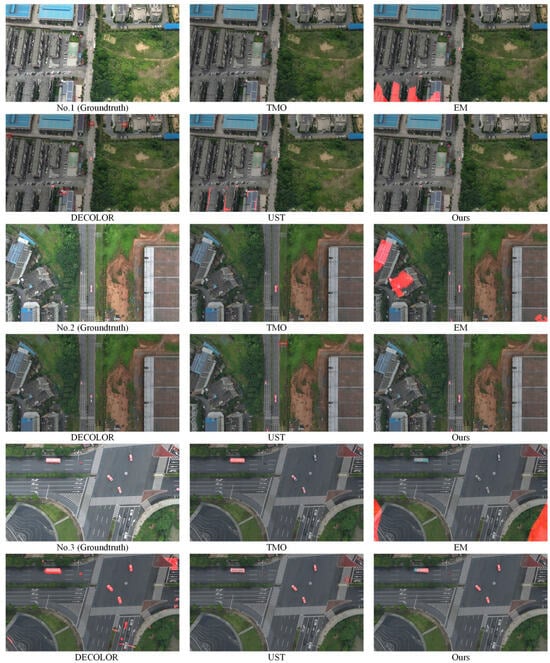

4.5. Qualitative Results

Figure 5 presents a comparison of the proposed method with several classical methods on examples from the UAVMD test set. As shown in Example No. 1 and No. 2, due to motion parallax and platform movements, the building edges and protruding poles are difficult to distinguish from genuine moving targets, leading to numerous false positives in methods such as EM, DECOLOR, and UST. In Example No. 3, homogeneous areas, such as road markings, also pose significant challenges for detecting real moving objects. The supervised VOS method TMO suffers from many missed detections when the distribution of the test data differs from its training data, resulting in inconsistent performance. By leveraging prior knowledge, including foreground sparsity and spatial consistency, the proposed method effectively mitigates these false positives. Additional qualitative results of the proposed method are provided in Appendix A.

Figure 5.

Qualitative comparison results of different methods. The method names are listed below the images, and the detection results are displayed on the original image in the form of weighted red masks. Key regions are emphasized using red bounding boxes.

4.6. Ablation Results

Table 3 presents the ablation results of the main components of the proposed method on our UAVMD dataset. The baseline [34] uses a classic 3D U-Net architecture, incorporating flow reconstruction loss and temporal consistency loss. The term ‘+sb’ denotes the addition of foreground sparse loss, ‘+sp’ represents the addition of spatial consistency loss, and ‘Ours’ refers to the final version, which includes the foreground sparse loss, spatial consistency loss, and the ASPP component. As shown, the foreground sparsity constraint yields a 28% improvement in the JI and a 9% improvement in precision compared to the baseline, significantly reducing false positives caused by motion parallax and the platform’s own motion. The addition of the spatial consistency constraint and the multi-scale ASPP module further improves the JI, Pr, and F1 scores in the drone-based scenarios.

Table 3.

Ablations of the designs.

4.7. Cross-Dataset Results

Figure 6 presents the test results of the proposed method across diverse scenarios and object sizes, noting that these data were completely unseen during training. The vehicles in the examples that were occluded were also successfully detected. The results demonstrate the strong cross-dataset generalization capability of our algorithm.

Figure 6.

Illustration results on unseen sequences. Examples 1 and 2 are collected by ourselves, while No. 3 is sourced from the VIVID dataset [5], Example 4 from the DAVIS sequence [4], Examples 5–7 from the BMS dataset [48], and Example 8 from the CDNet 2014 dataset [51]. The detected moving objects are highlighted with red masks, with the target number and optical flow magnitude displayed as text. Arrows indicate the direction of the optical flow associated with the targets.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we present a benchmark for UAV moving object detection. We introduce prior knowledge in UAV scenarios, including foreground sparsity and spatial consistency constraints, into the loss function and design a multi-scale unsupervised UAV moving object detection network based on optical flow. The network learns to detect moving objects by exploiting the differences in motion patterns under these constraints, significantly mitigating false positives caused by motion parallax and platform movement. Experimental results demonstrate the algorithm’s effectiveness and its cross-dataset generalization ability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.F. and G.W.; methodology, X.F.; software, X.F.; validation, X.F., Z.G. and J.C.; formal analysis, X.F.; data curation, H.J.; writing—original draft preparation, X.F.; writing—review and editing, Z.G., J.C. and H.J.; visualization, X.F.; project administration, G.W.; funding acquisition, G.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data sources are provided within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Pseudocode of the Proposed Method

Algorithm 1 presents the pseudocode of the proposed method. The image sequence is first processed by a pre-trained optical flow estimation network to generate dense inter-frame optical flow . During training, the computed optical flow is fed into a segmentation network to estimate the probability of each pixel belonging to the foreground or background layer . The L-BFGS algorithm then optimizes motion model parameters based on the segmentation results. These parameters are used to reconstruct the optical flow field, enabling computation of the optical flow reconstruction loss . Additionally, spatial consistency loss , temporal consistency loss and foreground sparse loss are derived from the network’s segmentation output. The total loss is minimized via backpropagation using the Adam optimizer to update the segmentation network parameters. For inference, optical flows are directly processed by the trained segmentation network to produce detection results .

| Algorithm A1 Proposed Moving Object Detection method | |

| 1: | procedure FlowPrepare) |

| 2: | |

| 3: | end procedure |

| 4: | procedure TrainingStep) |

| 5: | |

| 6: | |

| 7: | (Equation 3) |

| 8: | (Equations 4, 5 and 6) |

| 9: | |

| 10: | |

| 11: | end procedure |

| 12: | procedure InferenceStep) |

| 13: | |

| 14: | end procedure |

Appendix A.2. Example of Occlusion Scenarios

Figure A1 presents the test results of the proposed method in various occlusion scenarios. These include cases where moving objects are entering or exiting the scene, as well as instances of occlusion by trees or shadows. Since the method relies minimally on semantic cues, it effectively detects incomplete moving objects in these examples.

Figure A1.

Test results in scenes with partial occlusion. Examples from the UAVMD test set.

Appendix A.3. Example of Occlusion Scenarios

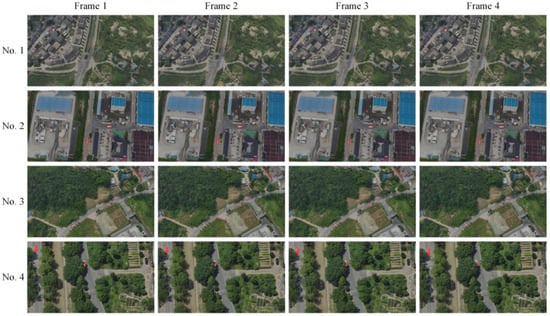

Figure A2 illustrates the continuous detection results in video sequences using the proposed method. By incorporating spatiotemporal consistency constraints, the method effectively leverages temporal cues, enabling continuous detection of moving targets across time in the example sequences. The effective detection results suggest the potential of the method for downstream applications such as target localization, velocity estimation, and tracking.

Figure A2.

Illustration of the continuous detection in time. Examples are drawn from the UAVMD test set.

References

- Zhou, X.; Yang, C.; Yu, W. Moving Object Detection by Detecting Contiguous Outliers in the Low-Rank Representation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2013, 35, 597–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, M.; Kumar, L.K.; Vipparthi, S.K. Mor-uav: A benchmark dataset and baselines for moving object recognition in uav videos. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Seattle, WA, USA, 12–16 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Koffka, K. Perception: An introduction to the Gestalt-theorie. Psychol. Bull. 1922, 19, 531–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perazzi, F.; Pont-Tuset, J.; McWilliams, B.; Van Gool, L.; Gross, M.; Sorkine-Hornung, A.; Zurich, E.T.H. Disney Research. A benchmark dataset and evaluation methodology for video object segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, R.; Zhou, X.; The, S.K. An open source tracking testbed and evaluation web site. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Workshop on Performance Evaluation of Tracking and Surveillance (PETS 2005), Breckenridge, CO, USA, 10 January 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Stauffer, C.; Grimson, W.E.L. Adaptive background mixture models for real-time tracking. In Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Fort Collins, CO, USA, 23–25 June 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Zivkovic, Z. Improved adaptive Gaussian mixture model for background subtraction. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR 2004), Cambridge, UK, 23–26 August 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D.-S. Effective Gaussian mixture learning for video background subtraction. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2005, 27, 827–832. [Google Scholar]

- Shakeri, M.; Zhang, H. COROLA: A sequential solution to moving object detection using low-rank approximation. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2016, 146, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElTantawy, A.; Shehata, M.S. KRMARO: Aerial Detection of Small-Size Ground Moving Objects Using Kinematic Regularization and Matrix Rank Optimization. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2019, 29, 1672–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marc, V.D.; Barnich, O. ViBE: A Powerful Random Technique to Estimate the Background in Video Sequences. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing, Taipei, Taiwan, 19–24 April 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh, Y.; Javed, O.; Kanade, T. Background Subtraction for Freely Moving Cameras. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Kyoto, Japan, 29 September–2 October 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, M.; Seversky, L. Subspace Tracking under Dynamic Dimensionality for Online Background Subtraction. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, Z.; Zhu, L. Foreground Detection with Deeply Learned Multi-Scale Spatial-Temporal Features. Sensors 2018, 18, 4269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, K.; Jang, W.-D.; Kim, C.-S. Background Subtraction Using Encoder-Decoder Structured Convolutional Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 14th IEEE International Conference on Advanced Video and Signal Based Surveillance (AVSS), Lecce, Italy, 29 August–1 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, L.A.; Keles, H.Y. Learning Multi-scale Features for Foreground Segmentation. Pattern Anal. Appl. 2018, 23, 1369–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teed, Z.; Deng, J. Raft: Recurrent All-Pairs Field Transforms for Optical Flow. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Shi, X.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Q.; Cheung, K.C.; Qin, H.; Dai, J.; Li, H. Flowformer: A Transformer Architecture for Optical Flow. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Zhu, C.; Kim, D. Fast Moving Object Detection with Non-Stationary Background. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2012, 67, 311–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugeau, A.; Pérez, P. Detection and segmentation of moving objects in complex scenes. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2009, 113, 459–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brox, T.; Malik, J. Object Segmentation by Long Term Analysis of Point Trajectories. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Heraklion, Crete, Greece, 5–11 September 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Zou, W.; Zhu, J.; Zhu, Z. Optical Flow Based Real-time Moving Object Detection in Unconstrained Scenes. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.04890. [Google Scholar]

- Sugimura, D.; Teshima, F.; Hamamoto, T. Online background subtraction with freely moving cameras using different motion boundaries. Image Vis. Comput. 2018, 76, 76–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Sun, X.; Yu, Q. Moving Object Detection under a Moving Camera via Background Orientation Reconstruction. Sensors 2020, 20, 3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Sun, X.; Yu, Q. Accurate moving object segmentation in unconstraint videos based on robust seed pixels selection. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2020, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokmakov, P.; Alahari, K.; Schmid, C. Learning motion patterns in videos. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Lamdouar, H.; Lu, E.; Zisserman, A.; Xie, W. Self supervised video object segmentation by motion grouping. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Lai, B.; Soatto, S. DyStaB: Unsupervised object segmentation via dynamic-static bootstrapping. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, T.; Li, J.; Wang, S.; Tao, R.; Shen, J. MATNet: Motion-Attentive Transition Network for Zero-Shot Video Object Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2020, 29, 8326–8338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, P.; Fu, K.; Wu, Z.; Fan, D.P.; Shen, J.; Shao, L. Full-Duplex Strategy for Video Object Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Qi, J.; Lu, H.; Wang, S.; Zhang, X. Learning Motion-Appearance Co-Attention for Zero-Shot Video Object Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury, S.; Karazija, L.; Laina, I.; Vedaldi, A.; Rupprecht, C. Guess What Moves: Unsupervised Video and Image Segmentation by Anticipating Motion. In Proceedings of the British Machine Vision Conference (BMVC), London, UK, 2022., 21–24 November.

- Meunier, E.; Badoual, A.; Bouthemy, P. EM-Driven Unsupervised Learning for Efficient Motion Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 4462–4473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meunier, E.; Bouthemy, P. Unsupervised Space-Time Network for Temporally-Consistent Segmentation of Multiple Motions. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Suhwan, C.; Lee, M.; Lee, S.; Park, C.; Kim, D.; Lee, S. Treating Motion as Option to Reduce Motion Dependency in Unsupervised Video Object Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 2–7 January 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Logoglu, K.B.; Lezki, H.; Yucel, M.K.; Ozturk, A.; Kucukkomurler, A.; Karagoz, B.; Erdem, E.; Erdem, A. Feature-Based Efficient Moving Object Detection for Low-Altitude Aerial Platforms. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops (ICCVW), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, M.; Smith, N.; Ghanem, B. A Benchmark and Simulator for UAV Tracking. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lezki, H.; Ozturk, I.A.; Akpinar, M.A.; Yucel, M.K.; Logoglu, K.B.; Erdem, A.; Erdem, E. Joint Exploitation of Features and Optical Flow for Real-Time Moving Object Detection on Drones. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV) Workshops, Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kalantar, B.; Mansor, S.B.; Halin, A.A.; Shafri, H.Z.M.; Zand, M. Multiple Moving Object Detection From UAV Videos Using Trajectories of Matched Regional Adjacency Graphs. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2017, 55, 5198–5213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siam, M.; Eikerdawy, S.; Gamal, M.; Abdel-Razek, M.; Jagersand, M.; Zhang, H. Real-Time Segmentation with Appearance, Motion and Geometry. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Madrid, Spain, 1–5 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Ye, D.H.; Kolsch, M.; Wachs, J.P.; Bouman, C.A. Fast and Robust UAV to UAV Detection and Tracking From Video. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. 2022, 10, 1519–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, M.; Shibasaki, R.; Shao, X.; Nagai, M. Automatic Extraction of Moving Objects from UAV-Borne Monocular Images Using Multi-View Geometric Constraints. In Proceedings of the International Micro Air Vehicle Conference and Competition (IMAV 2014), Delft, The Netherlands, 12–15 August 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Çiçek, Ö.; Abdulkadir, A.; Lienkamp, S.S.; Brox, T.; Ronneberger, O. 3D U-Net: Learning Dense Volumetric Segmentation from Sparse Annotation. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, Athens, Greece, 17–21 October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.; Nocedal, J. On the Limited Memory BFGS Method for Large Scale Optimization. Math. Program. 1989, 45, 503–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, B.; Schunck, B. Determining Optical Flow. Artif. Intell. 1981, 16, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.Z. Markov Random Field Modeling in Image Analysis; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; He, X.; Nguyen, T.Q. Moving Object Detection with a Freely Moving Camera via Background Motion Subtraction. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2017, 27, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Oreifej, O.; Shah, M. Action Recognition in Videos Acquired by a Moving Camera Using Motion Decomposition of Lagrangian Particle Trajectories. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Barcelona, Spain, 6–13 November 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hartley, R.; Zisserman, A. Multiple View Geometry in Computer Vision, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004; pp. 123–126. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Jodoin, P.M.; Porikli, F.; Konrad, J.; Benezeth, Y.; Ishwar, P. CDnet 2014: An Expanded Change Detection Benchmark Dataset. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).