High Connectivity in the Deep-Water Pagellus bogaraveo: Phylogeographic Assessment Across Mediterranean and Atlantic Waters

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Belcaid, S.; Benchoucha, S.; Pérez Gil, J.L.; Gil Herrera, J.; González Costas, F.; García Prieto, F.; Talbaoui, E.M.; El Arraf, S.; Hamdi, H.; Abid, N.; et al. Preliminary Joint Assessment of Pagellus Bogaraveo Stock of the Strait of Gibraltar Area between Spain and Morocco (GSAs 01 and 03). Paper Presented at the Working Group on Stock Assessment of Demersal Species (SCSA-SAC, GFCM). FAO-CopeMed II Occas Pap N° 15. Cent. Ocean. Vigo Madr. Spain 2018, 15, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Mytilineou, C.; Tsagarakis, K.; Bekas, P.; Anastasopoulou, A.; Kavadas, S.; Machias, A.; Haralabous, J.; Smith, C.J.; Petrakis, G.; Dokos, J.; et al. Spatial Distribution and Life-History Aspects of Blackspot Seabream Pagellus Bogaraveo (Osteichthyes: Sparidae). J. Fish. Biol. 2013, 83, 1551–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paruğ, Ş.; Cengiz, Ö. The Maximum Length Record of the Blackspot Seabream (Pagellus Bogaraveo Brünnich, 1768) for the Entire Aegean Sea and Turkish Territorial Waters. Turk. J. Agric. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 8, 2125–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockley, B.; Menezes, G.; Pinho, M.R.; Rogers, A.D. Genetic Population Structure in the Black-Spot Sea Bream (Pagellus Bogaraveo Brunnich, 1768) from the NE Atlantic. Mar. Biol. 2005, 146, 793–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilari, A.; Petrakis, G.; Tsamis, E. Aspects of the Biology of Blackspot Seabream (Pagellus Bogaraveo) in the Ionian Sea, Greece. Fish. Res. 2006, 77, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorance, P. History and Dynamics of the Overexploitation of the Blackspot Sea Bream (Pagellus Bogaraveo) in the Bay of Biscay. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2011, 68, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinho, M.; Diogo, H.; Carvalho, J.; Pereira, J.G. Harvesting Juveniles of Blackspot Sea Bream (Pagellus Bogaraveo) in the Azores (Northeast Atlantic): Biological Implications, Management, and Life Cycle Considerations. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2014, 71, 2448–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Onghia, G.; Indennidate, A.; Giove, A.; Savini, A.; Capezzuto, F.; Sion, L.; Vertino, A.; Maiorano, P. Distribution and Behaviour of Deep-Sea Benthopelagic Fauna Observed Using Towed Cameras in the Santa Maria Di Leuca Cold-Water Coral Province. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2011, 443, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sion, L.; Calculli, C.; Capezzuto, F.; Carlucci, R.; Carluccio, A.; Cornacchia, L.; Maiorano, P.; Pollice, A.; Ricci, P.; Tursi, A.; et al. Does the Bari Canyon (Central Mediterranean) Influence the Fish Distribution and Abundance? Prog. Ocean. 2019, 170, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoukh, M.; Berday, N.; Benziane, M.; Benchoucha, S.; Chiaar, A.; Malouli Idrissi, M. Reproductive Biology of the Blackspot Seabream Pagellus Bogaraveo (Brünnich, 1768) in the Moroccan Mediterranean Side of the Strait of Gibraltar. Cah Biol. Mar. 2021, 62, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICES. Working Group on the Biology and Assessment of Deep-Sea Fisheries Resources (WGDEEP); ICES: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Report of the Twenty-Fourth Session of the Scientific Advisory Committee on Fisheries, FAO Headquarters, Rome, Italy, 20–23 June 2023; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024; Volume 1421, ISBN 978-92-5-138376-6. [Google Scholar]

- Sanz-Fernández, V.; Gutiérrez-Estrada, J.C.; Pulido-Calvo, I.; Gil-Herrera, J.; Benchoucha, S.; el Arraf, S. Environment or Catches? Assessment of the Decline in Blackspot Seabream (Pagellus Bogaraveo) Abundance in the Strait of Gibraltar. J. Mar. Syst. 2019, 190, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Scientific Advisory Committee on Fisheries (SAC); FAO: Rome, Italy, 2017; pp. 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bargelloni, L.; Alarcon, J.A.; Alvarez, M.C.; Penzo, E.; Magoulas, A.; Reis, C.; Patarnello, T. Discord in the Family Sparidae (Teleostei): Divergent Phylogeographical Patterns across the Atlantic-Mediterranean Divide. J. Evol. Biol. 2003, 16, 1149–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñera, J.A.; Blanco, G.; Vázquez, E.; Sánchez, J.A. Genetic Diversity of Blackspot Seabream (Pagellus Bogaraveo) Populations Ov Spanish Coasts: A Preliminary Study. Mar. Biol. 2007, 151, 2153–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemos, A.; Freitas, A.I.; Fernandes, A.T.; Goncalves, R.; Jesus, J.; Andrade, C.; Brehm, A. Microsatellite Variability in Natural Populations of the Blackspot Seabream Pagellus Bogaraveo (Brunnick, 1768): A Database to Access Parentage Assignment in Aquaculture. Aquac. Res. 2006, 37, 1028–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.; Spiga, M.; Rodriguez, M.D.; Fiorentino, F.; Gil-Herrera, J.; Hernandez, P.; Hidalgo, M.; Johnstone, C.; Khemiri, S.; Mokhtar-Jamaï, K.; et al. Matching an Old Marine Paradigm: Limitless Connectivity in a Deep-Water Fish over a Large Distance. Animals 2023, 13, 2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunha, R.L.; Robalo, J.I.; Francisco, S.M.; Farias, I.; Castilho, R.; Figueiredo, I. Genomics Goes Deeper in Fisheries Science: The Case of the Blackspot Seabream (Pagellus Bogaraveo) in the Northeast Atlantic. Fish. Res. 2024, 270, 106891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robalo, J.I.; Farias, I.; Francisco, S.M.; Avellaneda, K.; Castilho, R.; Figueiredo, I. Genetic Population Structure of the Blackspot Seabream (Pagellus Bogaraveo): Contribution of MtDNA Control Region to Fisheries Management. Mitochondrial DNA Part A 2021, 32, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.H.E.; Chaisiri, K.; Saralamba, S.; Morand, S.; Thaenkham, U. Assessing the Suitability of Mitochondrial and Nuclear DNA Genetic Markers for Molecular Systematics and Species Identification of Helminths. Parasites Vectors 2021, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, N.; Sukumaran, S.; Jose, A.; Nisha, K.; Roul, S.K.; Rahangdale, S.; Kizhakudan, S.J.; Gopalakrishnan, A. Population Genetic Structure of Randall’s Threadfin Bream Nemipterus Randalli in Indian Waters Based on Mitochondrial and Nuclear Gene Sequences. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robalo, J.I.; Castilho, R.; Francisco, S.M.; Almada, F.; Knutsen, H.; Jorde, P.E.; Pereira, A.M.; Almada, V.C. Northern Refugia and Recent Expansion in the North Sea: The Case of the Wrasse Symphodus Melops (Linnaeus, 1758). Ecol. Evol. 2012, 2, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidalgo, M.; Hernández, P.; Vasconcellos, M. Transboundary Population Structure of Sardine, European Hake and Blackspot Seabream in the Alboran Sea and Adjacent Waters—A Multidisciplinary Approach; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024; ISBN 978-92-5-138856-3. [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand, J.A.; Gil de Sola, L.; Papaconstantinou, C.; Relini, G.; Souplet, A. The General Specifications of the MEDITS Surveys. Sci. Mar. 2002, 66, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce, M.; Infante, C.; Jiménez-Cantizano, R.M.; Pérez, L.; Manchado, M. Complete Mitochondrial Genome of the Blackspot Seabream, Pagellus Bogaraveo (Perciformes: Sparidae), with High Levels of Length Heteroplasmy in the WANCY Region. Gene 2008, 409, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljanabi, S. Universal and Rapid Salt-Extraction of High Quality Genomic DNA for PCR-Based Techniques. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 25, 4692–4693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostellari, L.; Bargelloni, L.; Penzo, E.; Patarnello, P.; Patarnello, T. Optimization of Single-Strand Conformation Polymorphism and Sequence Analysis of the Mitochondrial Control Region in Pagellus Bogaraveo (Sparidae, Teleostei): Rationalized Tools in Fish Population Biology. Anim. Genet. 1996, 27, 423–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, J.D.; Higgins, D.G.; Gibson, T.J. CLUSTAL W: Improving the Sensitivity of Progressive Multiple Sequence Alignment through Sequence Weighting, Position-Specific Gap Penalties and Weight Matrix Choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994, 22, 4673–4680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozas, J.; Ferrer-Mata, A.; Sánchez-DelBarrio, J.C.; Guirao-Rico, S.; Librado, P.; Ramos-Onsins, S.E.; Sánchez-Gracia, A. DnaSP 6: DNA Sequence Polymorphism Analysis of Large Data Sets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017, 34, 3299–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

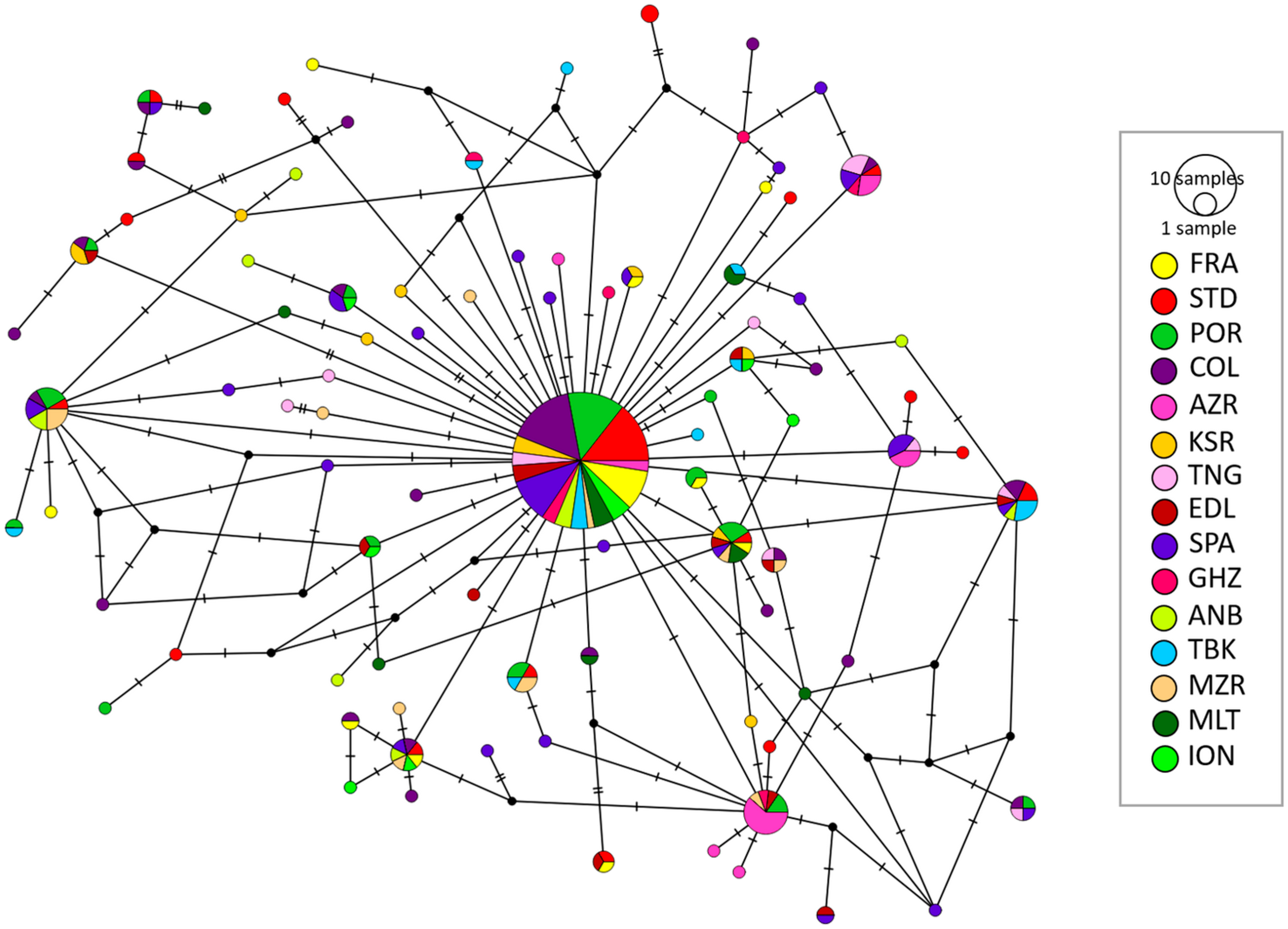

- Bandelt, H.J.; Forster, P.; Rohl, A. Median-Joining Networks for Inferring Intraspecific Phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1999, 16, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh, J.W.; Bryant, D. POPART: Full-feature Software for Haplotype Network Construction. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2015, 6, 1110–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, B.S.; Cockerham, C.C. Estimating F-Statistics for the Analysis of Population Structure. Evolution 1984, 38, 1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Excoffier, L.; Lischer, H.E.L. Arlequin Suite Ver 3.5: A New Series of Programs to Perform Population Genetics Analyses under Linux and Windows. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2010, 10, 564–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Excoffier, L.; Smouse, P.E.; Quattro, J.M. Analysis of Molecular Variance Inferred from Metric Distances among DNA Haplotypes: Application to Human Mitochondrial DNA Restriction Data. Genetics 1992, 131, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Team, R.C. R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Paradis, E.; Schliep, K. Ape 5.0: An Environment for Modern Phylogenetics and Evolutionary Analyses in R. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 526–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G.L.; Blanchet, F.G.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.R.; O’HAra, R.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.H.H.; Szoecs, E.; et al. Vegan: Community Ecology Package. Ordination Methods, Diversity Analysis and Other Functions for Community and Vegetation Ecologists; The Comprehensive R Archive Network: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- da Fonseca, R.R.; Campos, P.F.; Rey-Iglesia, A.; Barroso, G.V.; Bergeron, L.A.; Nande, M.; Tuya, F.; Abidli, S.; Pérez, M.; Riveiro, I.; et al. Population Genomics Reveals the Underlying Structure of the Small Pelagic European Sardine and Suggests Low Connectivity within Macaronesia. Genes 2024, 15, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinet, T.; Roussel, V.; Cheze, K.; Gagnaire, P.A. Spatial Gradients of Introgressed Ancestry Reveal Cryptic Connectivity Patterns in a High Gene Flow Marine Fish. Mol. Ecol. 2020, 29, 3857–3871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, M.I.; Lamb, P.D.; Coscia, I.; Murray, D.S.; Brown, M.; Cameron, T.C.; Davison, P.I.; Freeman, H.A.; Georgiou, K.; Grati, F.; et al. High-Density SNP Panel Provides Little Evidence for Population Structure in European Sea Bass (Dicentrarchus Labrax) in Waters Surrounding the UK. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2025, 82, fsaf064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintela, M.; García-Seoane, E.; Dahle, G.; Klevjer, T.A.; Melle, W.; Lille-Langøy, R.; Besnier, F.; Tsagarakis, K.; Geoffroy, M.; Rodríguez-Ezpeleta, N.; et al. Genetics in the Ocean’s Twilight Zone: Population Structure of the Glacier Lanternfish Across Its Distribution Range. Evol. Appl. 2024, 17, e70032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almada, F.; Francisco, S.M.; Lima, C.S.; Fitzgerald, R.; Mirimin, L.; Villegas-Ríos, D.; Saborido-Rey, F.; Afonso, P.; Morato, T.; Bexiga, S.; et al. Historical Gene Flow Constraints in a Northeastern Atlantic Fish: Phylogeography of the Ballan Wrasse Labrus Bergylta across Its Distribution Range. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2017, 4, 160773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, M.L.; Nelson, R.J.; Fevolden, S.-E.; Christiansen, J.S.; Præbel, K. Population Genetic Analysis of Euro-Arctic Polar Cod Boreogadus Saida Suggests Fjord and Oceanic Structuring. Polar Biol. 2016, 39, 969–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenne, R.; Bernaś, R.; Kijewska, A.; Poćwierz-Kotus, A.; Strand, J.; Petereit, C.; Plauška, K.; Sics, I.; Árnyasi, M.; Kent, M.P. SNP Genotyping Reveals Substructuring in Weakly Differentiated Populations of Atlantic Cod (Gadus Morhua) from Diverse Environments in the Baltic Sea. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 9738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.G. Animal Mitochondrial DNA as a Genetic Marker in Population and Evolutionary Biology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1989, 4, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandra, M.; Assis, J.; Martins, M.R.; Abecasis, D. Reduced Global Genetic Differentiation of Exploited Marine Fish Species. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 1402–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, P.W.; Arkhipkin, A.I.; Al-Khairulla, H. Genetic Structuring of Patagonian Toothfish Populations in the Southwest Atlantic Ocean: The Effect of the Antarctic Polar Front and Deep-Water Troughs as Barriers to Genetic Exchange. Mol. Ecol. 2004, 13, 3293–3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allio, R.; Donega, S.; Galtier, N.; Nabholz, B. Large Variation in the Ratio of Mitochondrial to Nuclear Mutation Rate across Animals: Implications for Genetic Diversity and the Use of Mitochondrial DNA as a Molecular Marker. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017, 34, 2762–2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeSalle, R.; Schierwater, B.; Hadrys, H. MtDNA: The Small Workhorse of Evolutionary Studies. Front. Biosci.—Landmark 2017, 22, 873–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyer, E.; Zietkiewicz, E.; Rochowski, A.; Yotova, V.; Puymirat, J.; Labuda, D. Phylogenetic and Familial Estimates of Mitochondrial Substitution Rates: Study of Control Region Mutations in Deep-Rooting Pedigrees. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001, 69, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taboun, Z.S.; Walter, R.P.; Ovenden, J.R.; Heath, D.D. Spatial and Temporal Genetic Variation in an Exploited Reef Fish: The Effects of Exploitation on Cohort Genetic Structure. Evol. Appl. 2021, 14, 1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florencio, M.; Patiño, J.; Nogué, S.; Traveset, A.; Borges, P.A.V.; Schaefer, H.; Amorim, I.R.; Arnedo, M.; Ávila, S.P.; Cardoso, P.; et al. Macaronesia as a Fruitful Arena for Ecology, Evolution, and Conservation Biology. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 9, 718169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, J.P.; Alves, P.C.; Amorim, I.R.; Lopes, R.J.; Moura, M.; Myers, E.; Sim-sim, M.; Sousa-Santos, C.; Alves, M.J.; Borges, P.A.V.; et al. Building a Portuguese Coalition for Biodiversity Genomics. NPJ Biodivers. 2024, 3, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, I.; Harrison, C.S.; Caldeira, R.M.A. The Role of the Azores Archipelago in Capturing and Retaining Incoming Particles. J. Mar. Syst. 2016, 154, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.S.; Hawkins, S.; Monteiro, L.R.; Alves, M.; Isidro, E.J. Marine Research, Resources and Conservation in the Azores. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 1995, 5, 311–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, L.; Curto, M.; Waeschenbach, A.; Berning, B.; Santos, A.M.; Ávila, S.P.; Meimberg, H. Population Genetic Structure and Ecological Differentiation in the Bryozoan Genus Reteporella across the Azores Archipelago (Central North Atlantic). Heliyon 2024, 10, e38765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazão, H.C.; Prien, R.D.; Schulz-Bull, D.E.; Seidov, D.; Waniek, J.J. The Forgotten Azores Current: A Long-Term Perspective. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 842251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, D.J.; Monro, K.; Bode, M.; Keough, M.J.; Swearer, S. Phenotype–Environment Mismatches Reduce Connectivity in the Sea. Ecol. Lett. 2010, 13, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadal, A.I.; Sammartino, S.; García-Lafuente, J.; Sánchez Garrido, J.C.; Gil-Herrera, J.; Hidalgo, M.; Hernández, P. Hydrodynamic Connectivity and Dispersal Patterns of a Transboundary Species (Pagellus bogaraveo) in the Strait of Gibraltar and Adjacent Basins. Fish. Ocean. 2022, 31, 384–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

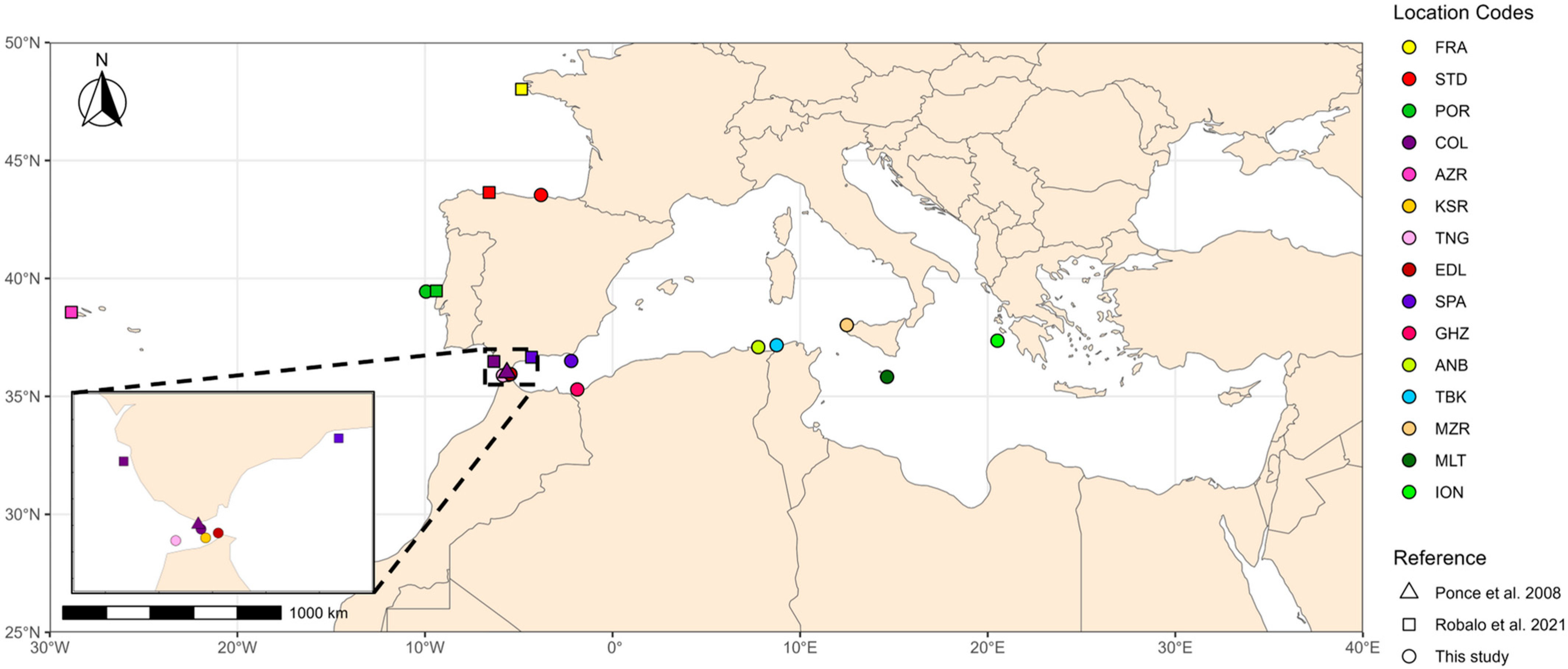

| Regional Sea/Macro Areas | Country | Location Code | This study * | Robalo et al. 2021 [20] * | Ponce et al. 2008 [26] * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atlantic Ocean | France | FRA | 21 | ||

| Spain | STD | 15 | 22 | ||

| Portugal | POR | 14 | 25 | ||

| Spain | COL | 15 | 23 | 2 | |

| Portugal | AZR | 20 | |||

| Strait of Gibraltar | Morocco | KSR | 14 | ||

| TNG | 14 | ||||

| EDL | 15 | ||||

| Alboran Sea | Spain | SPA-18 | 10 | 16 | |

| SPA-19 | 15 | ||||

| Alboran Sea/Balearic Sea | Algeria | GHZ | 9 | ||

| Balearic Sea | ANB | 13 | |||

| Balearic Sea/Tyrrhenian Sea | Tunisia | TBK | 15 | ||

| Strait of Sicily | Italy | MZR | 14 | ||

| Malta | MLT | 15 | |||

| Ionian Sea | Greece | ION | 12 | ||

| Total n° | 190 | 127 | 2 |

| Population Sample | N. | n | Hd | SD | π |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FRA | 21 | 11 | 0.781 | 0.094 | 0.00438 |

| STD | 37 | 18 | 0.767 | 0.075 | 0.00521 |

| POR | 37 | 16 | 0.808 | 0.064 | 0.00454 |

| COL | 42 | 24 | 0.839 | 0.058 | 0.00543 |

| AZR | 20 | 7 | 0.805 | 0.068 | 0.00321 |

| KSR | 14 | 10 | 0.923 | 0.06 | 0.00457 |

| TNG | 14 | 9 | 0.901 | 0.062 | 0.00514 |

| EDL | 15 | 11 | 0.905 | 0.072 | 0.00522 |

| SPA | 41 | 24 | 0.898 | 0.042 | 0.00524 |

| GHZ | 9 | 6 | 0.833 | 0.127 | 0.00263 |

| ANB | 13 | 8 | 0.859 | 0.089 | 0.00521 |

| TBK | 15 | 9 | 0.876 | 0.07 | 0.00396 |

| MZR | 14 | 10 | 0.945 | 0.045 | 0.00447 |

| MLT | 15 | 9 | 0.886 | 0.069 | 0.00544 |

| ION | 12 | 7 | 0.773 | 0.128 | 0.00379 |

| Total n° | 319 | 88 | 0.839 | 0.021 | 0.00477 |

| AMOVA Grouping | Percentage of Variation | Fixation Index | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMOVA 1, one group | |||

| Among populations | 2.04 | ||

| Within populations | 97.96 | 0.02042 | 0.00293 * |

| AMOVA 2, six groups | |||

| Among groups | −0.68 | −0.00679 | 0.61681 |

| Among populations within groups | 2.56 | 0.02546 | 0 |

| Within populations | 98.12 | 0.01885 | 0.00293 * |

| AMOVA 3, seven groups | |||

| Among groups | 2.95 | 0.02954 | 0.00489 * |

| Among populations within groups | −0.40 | −0.00167 | 0.00587 * |

| Within populations | 97.44 | 0.02558 | 0.00098 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Spiga, M.; Catalano, G.; Piattoni, F.; Ferrari, A.; Johnstone, C.; Mokhtar-Jamaï, K.; Pérez, M.; Fiorentino, F.; Hidalgo, M.; Cariani, A. High Connectivity in the Deep-Water Pagellus bogaraveo: Phylogeographic Assessment Across Mediterranean and Atlantic Waters. Fishes 2025, 10, 527. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10100527

Spiga M, Catalano G, Piattoni F, Ferrari A, Johnstone C, Mokhtar-Jamaï K, Pérez M, Fiorentino F, Hidalgo M, Cariani A. High Connectivity in the Deep-Water Pagellus bogaraveo: Phylogeographic Assessment Across Mediterranean and Atlantic Waters. Fishes. 2025; 10(10):527. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10100527

Chicago/Turabian StyleSpiga, Martina, Giusy Catalano, Federica Piattoni, Alice Ferrari, Carolina Johnstone, Kenza Mokhtar-Jamaï, Montse Pérez, Fabio Fiorentino, Manuel Hidalgo, and Alessia Cariani. 2025. "High Connectivity in the Deep-Water Pagellus bogaraveo: Phylogeographic Assessment Across Mediterranean and Atlantic Waters" Fishes 10, no. 10: 527. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10100527

APA StyleSpiga, M., Catalano, G., Piattoni, F., Ferrari, A., Johnstone, C., Mokhtar-Jamaï, K., Pérez, M., Fiorentino, F., Hidalgo, M., & Cariani, A. (2025). High Connectivity in the Deep-Water Pagellus bogaraveo: Phylogeographic Assessment Across Mediterranean and Atlantic Waters. Fishes, 10(10), 527. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10100527