Influence of the Polarizing Magnetic Field and Volume Fraction of Nanoparticles in a Ferrofluid on the Specific Absorption Rate (SAR) in the Microwave Range

Abstract

1. Introduction

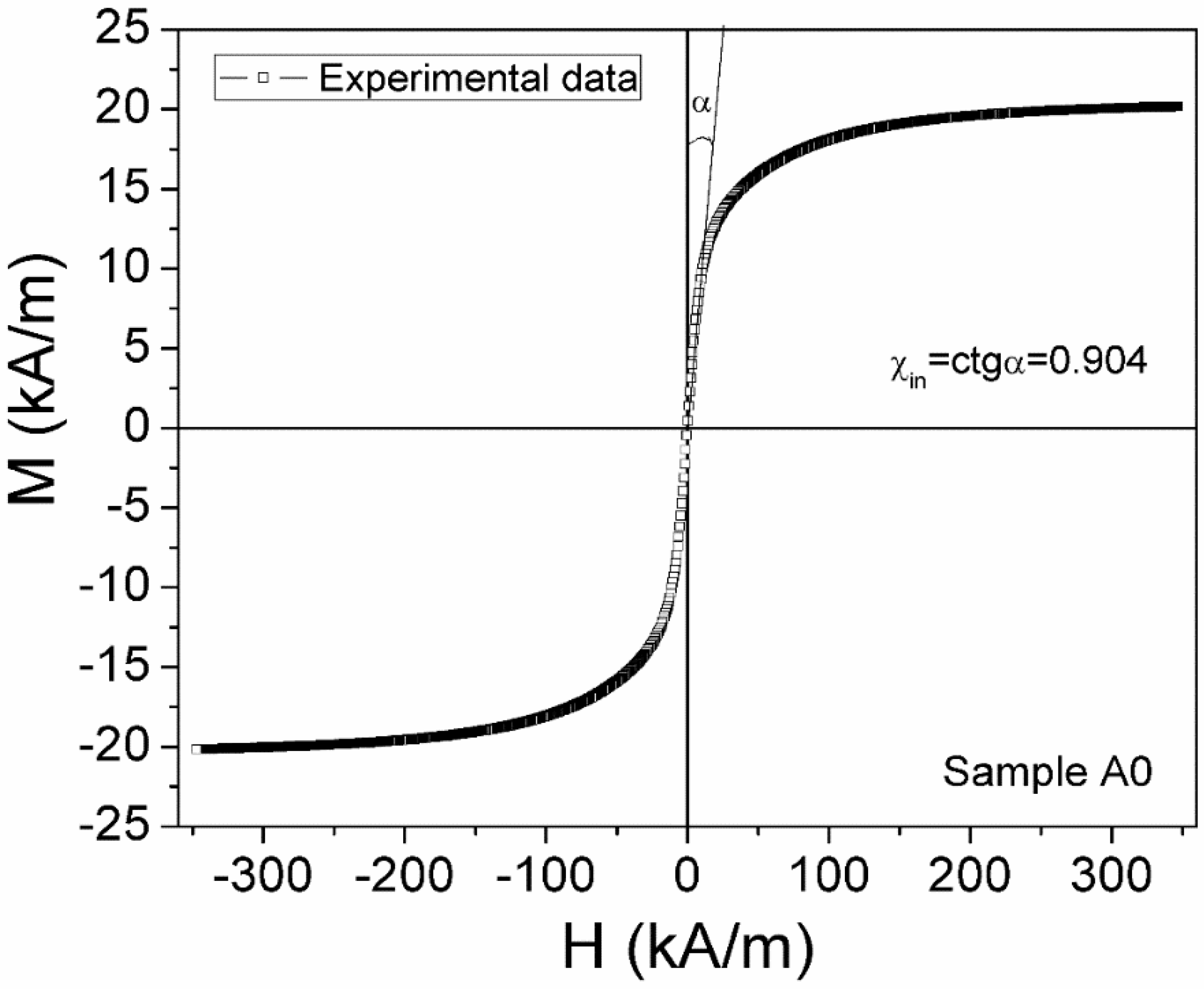

2. Samples Characterization and Experimental

3. Results and Discussions

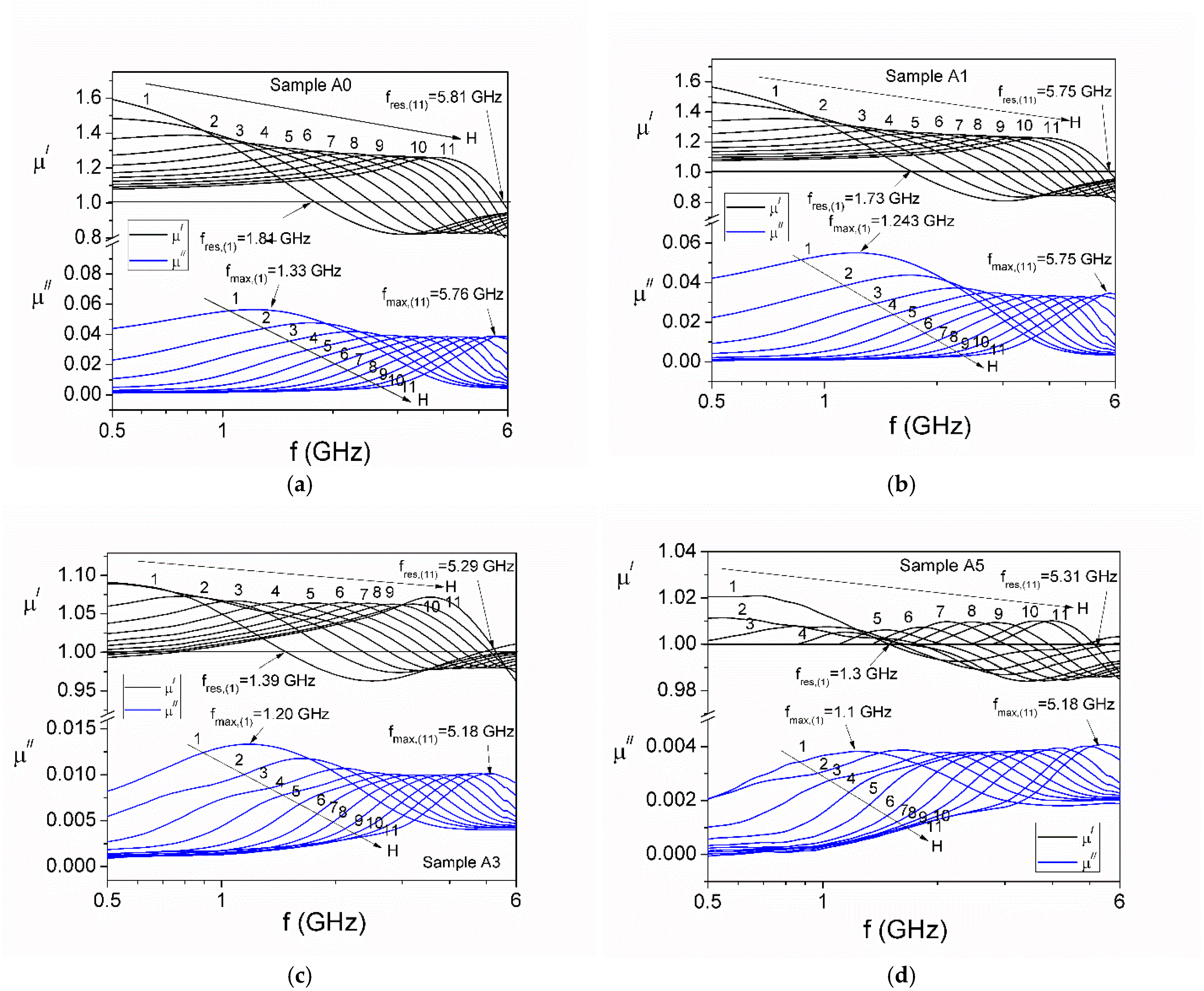

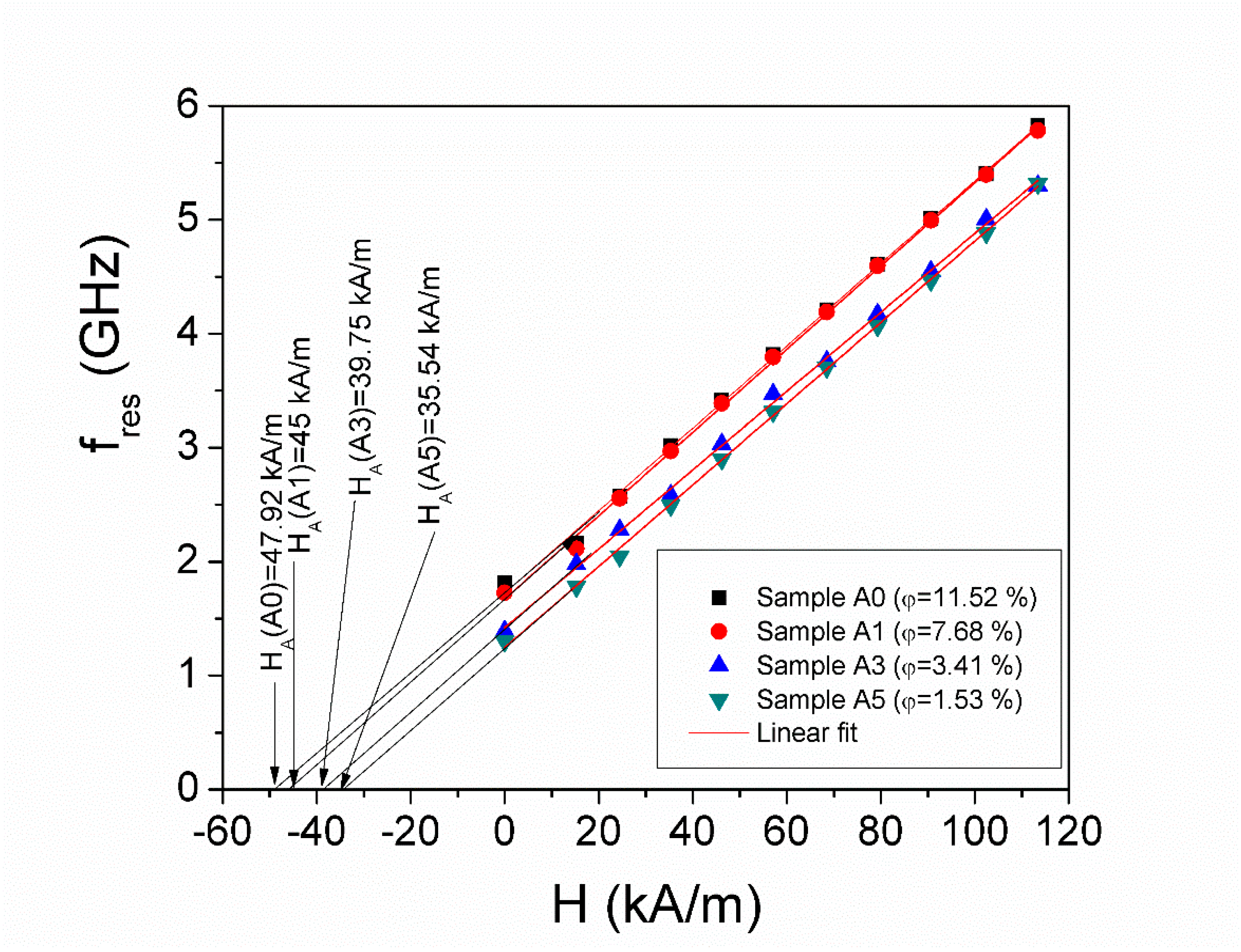

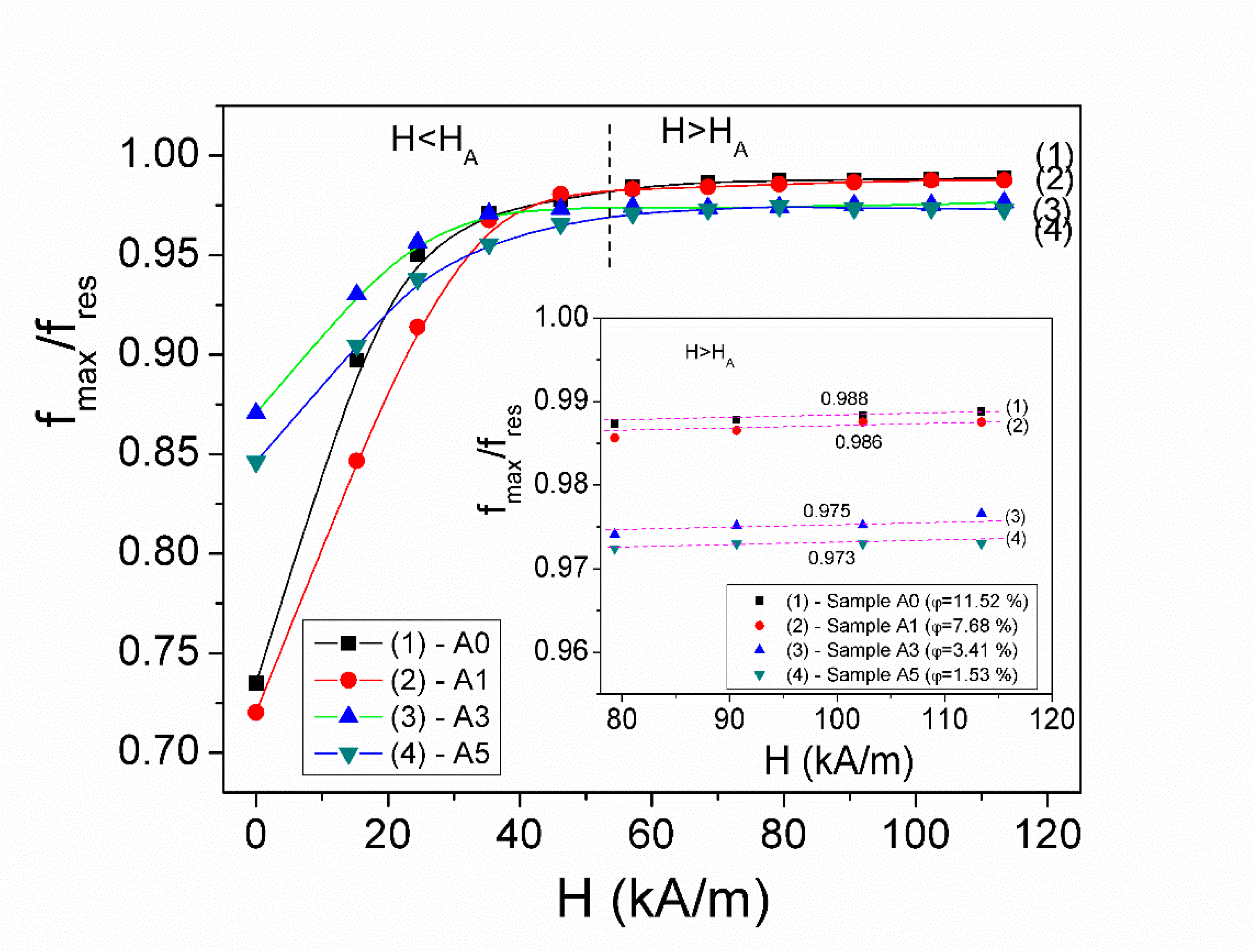

3.1. Complex Magnetic Permeability in Microwave Range

3.2. Specific Absorption Rate (SAR) in Microwave Range

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hartman, K.B.; Wilson, L.J.; Rosenblum, M.G. Detecting and treating cancer with nanotechnology. Mol. Diagn. Ther. 2008, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabir, S.; Bin Thani, A.S.; Abbas, Q. Nanotechnology in cancer treatment: Revolutionizing strategies against drug resistance. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 13, 1548588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adzavon, K.P.; Zhao, W.; He, X.; Sheng, W. Ferroptosis resistance in cancer cells: Nanoparticles for combination therapy as a solution. Front. in Pharmac. 2024, 15, 1416382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, M.; Yokoyama, Y.; Nagata, K. Effect of Particle Size and Relative Density on Powdery Fe3O4 Microwave Heating. J. Microw. Power Electromagn. Energy 2010, 44, 198–206. [Google Scholar]

- Debnath, S.K.; Srivastava, R. Drug Delivery With Carbon-Based Nanomaterials as Versatile Nanocarriers: Progress and Prospects. Front. Nanotechnol. 2021, 3, 644564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beh, C.Y.; Prajnamitra, R.P.; Chen, L.L.; Hsieh, P.C.-H. Advances in biomimetic nanoparticles for targeted cancer therapy and diagnosis. Molecules 2021, 26, 5052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, M.; Xu, M.; Lin, W.; He, H.; He, C. Graphene Oxide Research: Current Developments and Future Directions. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutz, S.; Hergt, R. Magnetic nanoparticle heating and heat transfer on a microscale: Basic principles, realities and physical limitations of hyperthermia for tumour therapy. Int. J. Hyperthermia 2013, 29, 790–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pucci, C.; Degl’Innocenti, A.; Gümüş, M.B.; Ciofani, G. Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for magnetic hyperthermia: Recent advancements, molecular effects, and future directions in the omics era. Biomater. Sci. 2022, 10, 2103–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Wei, B.; Qian, K.; Yao, Z.; Chen, P.; Tan, R.; Yi, P.; Jin, L.; Wang, M. Broadband electromagnetic wave absorption of Ni0.5Zn0.5Nd0.04Fe1.96O4 ferrites modified by nano-silver particles. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 6351–6360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, A.; Clausell, C.; Jarque, J.C.; Nuño, L. Magnetic complex permeability (imaginary part) dependence on the microstructure of a Cu-doped Ni–Zn-polycrystalline sintered ferrite. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 14558–14566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsufuji, T.; Miyake, M.; Naka, N.; Mochizuki, M.; Kogo, S.; Kajita, T.; Shimizu, Y.; Itoh, M.; Hasegawa, T.; Shimose, S.; et al. Orbital and magnetic ordering and domain-wall conduction in ferrimagnet La5Mo4O16. Phys. Rev. Res. 2021, 3, 013105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, W. Thermal Fluctuations of a Single-Domain Particle. Phys. Rev. B 1963, 130, 1677–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.R.; Shliomis, M.I. Relaxation Phenomena in Condensed Matter. Adv. Chem. Phys. 1994, 87, 595–751. [Google Scholar]

- Marin, C.N.; Malaescu, I.; Sfirloaga, P.; Teusdea, A. Electric and magnetic properties of a composite consisting of silicone rubber and ferrofluid. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2021, 101, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadtya, A.S.; Tripathy, D.; Rout, L.; Moharana, S. Graphene Oxide, It’s Surface Functionalisation, Preparation and Properties of Polymer-Based Composites: A Review. Compos. Interfaces 2024, 31, 29–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosensweig, R.E. Ferrohydrodynamics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, M.; Bhandari, A. Advancement in biomedical applications of ferrofluids. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2025, 47, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fannin, P.C. Use of Ferromagnetic Resonance Measurements in Magnetic Fluids. J. Mol. Liquids 2004, 114, 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Marin, C.N.; Malaescu, I.; Fannin, P.C. Theoretical Evaluation of the Heating Rate of Ferrofluids. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2015, 119, 1199–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunoiu, O.M.; Matu, G.; Marin, C.N.; Malaescu, I. Investigation of some thermal parameters of ferrofluids in the presence of a static magnetic field. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2020, 498, 166132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.jpcfrance.eu/technical-informations/heating-systems/table-of-liquids-specific-heat/ (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Available online: https://www.engineeringtoolbox.com/specific-heat-solids-d_154.html (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Gabor, L.; Minea, R.; Gabor, D. Magnetic Liquids Filtering Process. RO Patent 108851, 30 September 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Malaescu, I.; Gabor, L.; Claici, F.; Stefu, N. Study of some magnetic properties of ferrofluids filtered in magnetic field gradient. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2000, 222, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercuta, A. Sensitive AC hysteresigraph of extended driving field capability. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2020, 69, 1643–1651. [Google Scholar]

- Chantrell, R.W.; Popplewell, J.; Charles, S.W. Measurements of particle size distribution parameters in ferrofluids. IEEE Trans. Magn. 1978, 14, 975–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fannin, P.C.; MacOireachtaigh, C.; Couper, C. An Improved Technique for the Measurement of the Complex Susceptibility of Magnetic Colloids in the Microwave Region. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2010, 322, 2428–2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landau, L.D.; Lifshitz, E.M.; Sovjetunion, P.Z. Reprinted in Collected Works of Landau; Pergamon Press: London, UK, 1965; Volume 8, pp. 153–169. [Google Scholar]

- Shliomis, M.I.; Raikher, Y.L. Experimental Investigations of Magnetic Fluids. IEEE Trans. Magn. Magn. 1980, 16, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raikher, Y.L.; Stepanov, V.I. Intrinsic Magnetic Resonance in Nanoparticles: Landau Damping in the Collision Less Regime. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2002, 242, 1021–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dormann, J.L.; Bessais, L.; Fiorani, D. A dynamic study of small interacting particles: Superparamagnetic model and spin-glass laws. J. Phys. Chem. 1988, 21, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shtrikman, S.; Wohlfarth, E.P. The theory of the Vogel-Fulcher law of spin glasses. Phys. Lett. A 1981, 85, 467–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calero-Diaz del Castillo, V.L.; Rinaldi, C. Effect of Sample Concentration on the Determination of the Anisotropy Constant of Magnetic Nanoparticles. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2010, 46, 852–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco-Henao, J.M.; Muraca, D.; Sánchez, F.H.; Zélis, P.M. Determination of the effective anisotropy of magnetite/maghemite nanoparticles from Mössbauer effect spectra. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2022, 55, 335302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, J.M.; Lima, E., Jr.; Zysler, R.D.; Duque, J.G.S.; De Biasi, E.; Knobel, M. Effective anisotropy field variation of magnetite nanoparticles with size reduction. Eur. Phys. J. B 2008, 64, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahmann, T.; Rösch, E.L.; Enpuku, K.; Yoshida, T.; Ludwig, F. Determination of the Effective Anisotropy Constant of Magnetic Nanoparticles—Comparison between Two Approaches. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2021, 519, 167402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickford, L.R. Ferromagnetic Resonance Absorption in Magnetite Single Crystals. Phys. Rev. 1950, 78, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaescu, I.; Marin, C.N. Study of Magnetic Fluids by Means of Magnetic Spectroscopy. Physica B Condens. Matter. 2005, 365, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fannin, P.C.; Marin, C.N. Determination of the Landau-Lifshitz damping parameter by means of complex susceptibility measurements. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2006, 299, 425–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosensweig, R.E. Heating Magnetic Fluid with Alternating Magnetic Field. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2002, 252, 370–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urtizberea, A.; Natividad, E.; Arizaga, A.; Castro, M.; Mediano, A. Specific Absorption Rates and Magnetic Properties of Ferrofluids with Interaction Effects at Low Concentrations. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 4916–4922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales-Weimuller, M.; Zeisberger, M.; Krishnan, K.M. Size dependant heating rates of iron oxide nanoparticles for magnetic fluid hyperthermia. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2009, 321, 1947–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garaio, E.; Sandre, O.; Collantes, J.M.; Garcia, J.A.; Mornet, S.; Plazaola, F. Specific Absorption Rate Dependence on Temperature in Magnetic Field Hyperthermia Measured by Dynamic Hysteresis Losses (Ac Magnetometry). Nanotechnology 2015, 26, 015704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallumadil, M.; Tada, M.; Nakagawa, T.; Abe, M.; Southern, P.; Pankhurst, Q.A. Suitability of commercial colloids for magnetic hyperthermia. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2009, 321, 1509–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildeboer, R.R.; Southern, P.; Pankhurst, Q.A. On the reliable measurement of specific absorption rates and intrinsic loss parameters in magnetic hyperthermia materials. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2014, 47, 495003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardari, D.; Verg, N. Cancer treatment with hyperthermia. In Current Cancer Treatment–Novel Beyond Conventional Approaches; Ozdemir, O., Ed.; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2011; pp. 454–474. [Google Scholar]

- Gas, P. Essential facts on the history of hyperthermia and their connections with electromedicine. Prz. Elektrotechniczny 2011, 87, 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Thiesen, B.; Jordan, A. Clinical applications of magnetic nanoparticles for hyperthermia. Int. J. Hyperthermia 2008, 24, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivia, L.; Lanier, O.; Korotych, I.; Monsalve, A.G.; Wable, D.; Savliwala, S.; Grooms, N.W.F.; Nacea, C.; Tuitt, O.R.; Dobson, J. Evaluation of magnetic nanoparticles for magnetic fluid hyperthermia. Int. J. Hyperthermia 2019, 36, 686–700. [Google Scholar]

- Kozissnik, B.; Bohorquez, A.C.; Dobson, J.; Rinaldi, C. Magnetic fluid hyperthermia: Advances, challenges, and opportunity. Int. J. Hyperthermia 2013, 29, 706–714. [Google Scholar]

- Stoner, E.; Wohlfarth, E. A mechanism of magnetic hysteresis in heterogeneous alloys. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. A Mat. Phys. Sci. 1947, 240, 559–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolov, A.; Apostolova, I.; Wesselinowa, J. Specific absorption rate in Zn-doted ferrites for self-controlled magnetic hyperthermia. Eur. Phys. J. B 2019, 92, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrey, J.; Mehaoui, B.; Respaud, M. Simple models for dynamic hysteresis loop calculations of magnetic single-domain nanoparticles: Application to magnetic hyperthermia optimization. J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 109, 083921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molcan, M.; Skumiel, A.; Timko, M.; Safarik, I.; Zolochevska, K.; Kopcansky, P. Tuning of Magnetic Hyperthermia Response in the Systems Containing Magnetosomes. Molecules 2022, 27, 5605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca, A.G.; Wiese, B.; Timmis, J.; Vallejo-Fernandez, G.; O’Grady, K. Effect of Frequency and Field Amplitude in Magnetic Hyperthermia. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2012, 48, 4054–4057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apsotolov, A.T.; Apostolova, I.N.; Wesselinowa, J.M. Ferrimagnetic nanoparticles for self-controlled magnetic hyperthermia. Eur. Phys. J. B 2013, 86, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balanov, V.A.; Kiseleva, A.P.; Krivoshapkina, E.F.; Kashtanov, E.A.; Gimaev, R.R.; Zverev, V.I.; Krivoshapkin, P.V. Synthesis of (Mn(1−x)Znx)Fe2O4 nanoparticles for magnetocaloric applications. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Techn. 2020, 95, 795–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Samples | HA (kA/m) | γ (s−1A−1m) | Keff (J/m3) | g |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A0 (φ = 11.52%) | 47.92 | 2.27 × 105 | 1.44 × 104 | 2.04 |

| A1 (φ = 7.68%) | 45.00 | 2.28 × 105 | 1.35 × 104 | 2.05 |

| A3 (φ = 3.41%) | 39.75 | 2.20 × 105 | 1.19 × 104 | 2.00 |

| A5 (φ = 1.53%) | 35.54 | 2.24 × 105 | 1.07 × 104 | 2.00 |

| Samples | A0 (φ = 11.52%) | A1 (φ = 7.68%) | A3 (φ = 3.41%) | A5 (φ = 1.53%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency (GHz) | 2.5 | 3 | 4 | 2.5 | 3 | 4 | 2.5 | 3 | 4 | 2.5 | 3 | 4 |

| Hmax(SAR) (kA/m) | 23.18 | 37.45 | 67.20 | 24.14 | 37.78 | 67.50 | 32.40 | 48.20 | 83.69 | 46.21 | 62.01 | 87.33 |

| SARmax (W/kg) | 8.24 | 8.74 | 11.52 | 7.86 | 8.28 | 11.17 | 2.69 | 3.05 | 4.16 | 1.08 | 1.28 | 1.79 |

| Hmax(ILP) (kA/m) | 24.40 | 39.41 | 66.84 | 25.06 | 39.88 | 67.79 | 32.00 | 52.74 | 85.36 | 38.32 | 63.11 | 90.72 |

| ILPmax (nHm2kg−1) | 0.129 | 0.119 | 0.105 | 0.123 | 0.114 | 0.100 | 0.043 | 0.042 | 0.041 | 0.018 | 0.017 | 0.017 |

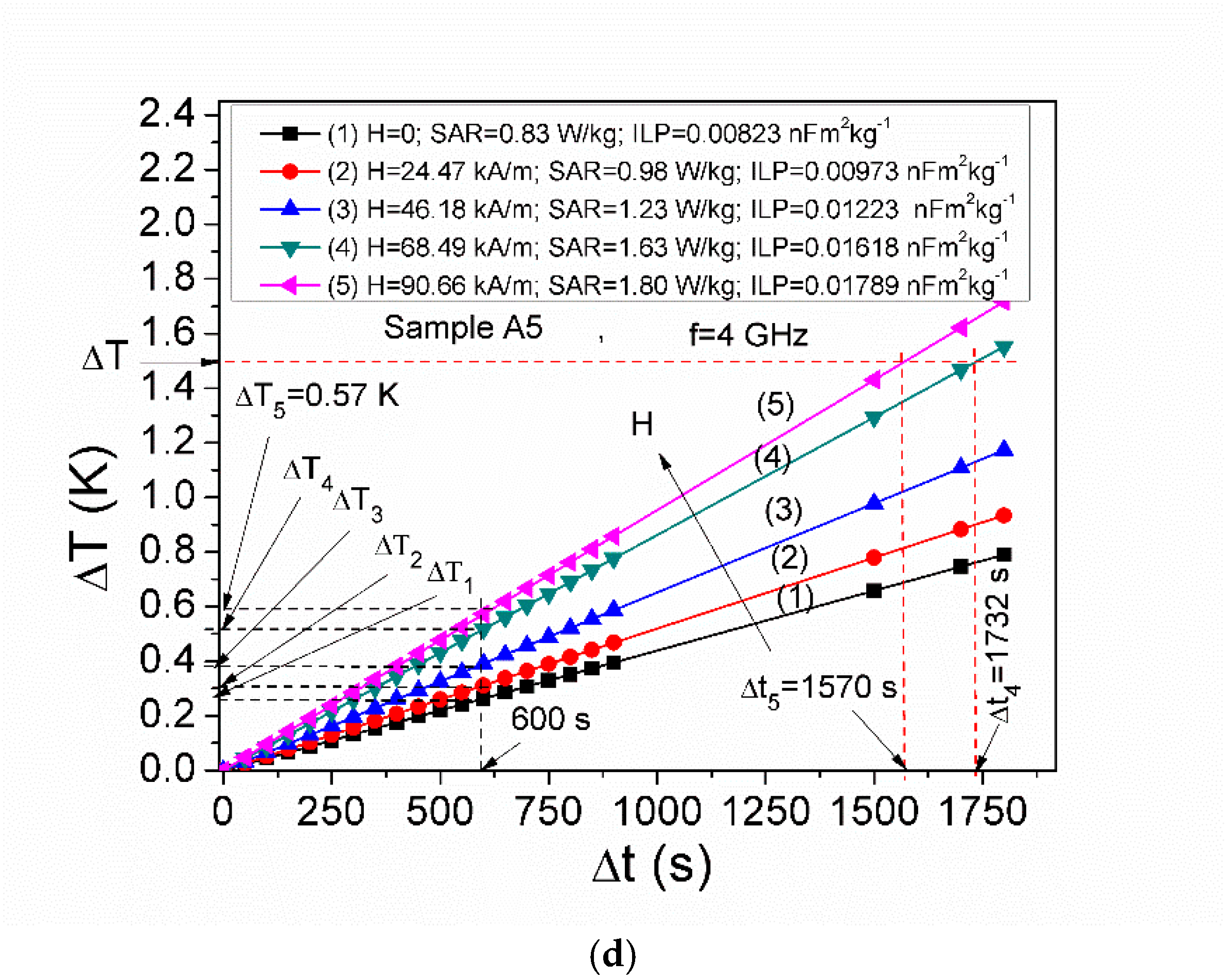

| Condition | for ΔT = 1.5 K = const. | for Δt = 600 s = const. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H (kA/m) | 0 | 24.47 | 46.18 | 68.49 | 0 | 24.47 | 46.18 | 68.49 |

| time (Δt (s)) | Δt1 | Δt2 | Δt3 | Δt4 | - | - | - | - |

| temperature (ΔT (K)) | - | - | - | - | ΔT1 | ΔT2 | ΔT3 | ΔT4 |

| A0 (φ = 11.52%) | 750 | 416 | 215 | 170 | 1.1 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 5.0 |

| A1 (φ = 7.68%) | 874 | 513 | 250 | 200 | 0.9 | 1.7 | 3.6 | 4.5 |

| A3 (φ = 3.41%) | 1509 | 1245 | 896 | 664 | 0.59 | 0.72 | 1.0 | 1.3 |

| A5 (φ = 1.53%) | ~3600 | ~3000 | ~2400 | 1732 | 0.25 | 0.31 | 0.38 | 0.51 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Malaescu, I.; Fannin, P.C.; Marin, C.N.; Bunoiu, M.O. Influence of the Polarizing Magnetic Field and Volume Fraction of Nanoparticles in a Ferrofluid on the Specific Absorption Rate (SAR) in the Microwave Range. Magnetochemistry 2026, 12, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/magnetochemistry12010005

Malaescu I, Fannin PC, Marin CN, Bunoiu MO. Influence of the Polarizing Magnetic Field and Volume Fraction of Nanoparticles in a Ferrofluid on the Specific Absorption Rate (SAR) in the Microwave Range. Magnetochemistry. 2026; 12(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/magnetochemistry12010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleMalaescu, Iosif, Paul C. Fannin, Catalin N. Marin, and Madalin O. Bunoiu. 2026. "Influence of the Polarizing Magnetic Field and Volume Fraction of Nanoparticles in a Ferrofluid on the Specific Absorption Rate (SAR) in the Microwave Range" Magnetochemistry 12, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/magnetochemistry12010005

APA StyleMalaescu, I., Fannin, P. C., Marin, C. N., & Bunoiu, M. O. (2026). Influence of the Polarizing Magnetic Field and Volume Fraction of Nanoparticles in a Ferrofluid on the Specific Absorption Rate (SAR) in the Microwave Range. Magnetochemistry, 12(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/magnetochemistry12010005