Hydroxypropyl-β-Cyclodextrin Improves Removal of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons by Fe3O4 Nanocomposites

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

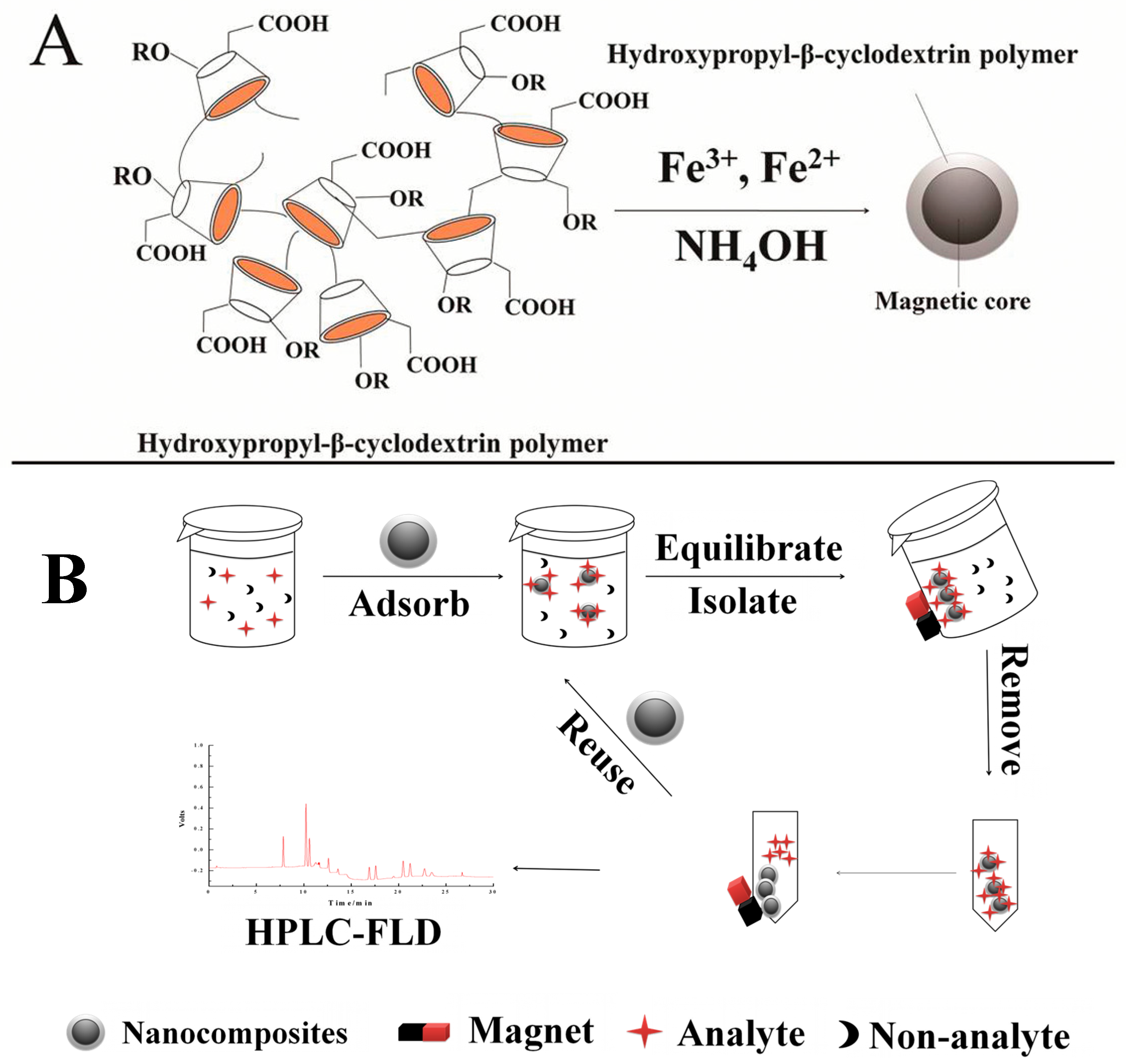

2.2. Synthesis of HP-β-CDCP/Fe3O4 Nanocomposites

2.3. Analytical Technique

2.4. Adsorption Kinetics

2.5. Adsorption Isotherms

2.6. Adsorption Thermodynamics

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of HP-β-CDCP/Fe3O4 Nanocomposites

3.2. Effects of Operation Parameters on PAH Removal

3.2.1. Effect of HP-β-CDCP

3.2.2. Effect of pH

3.2.3. Effect of Extraction Time

3.2.4. Effect of Nano-Adsorbent Dosage

3.2.5. Effect of Sample Volume

3.3. Adsorption Kinetics of HP-β-CDCP/Fe3O4 Nanocomposites

3.4. Adsorption Isotherms of HP-β-CDCP/Fe3O4 Nanocomposites

3.5. Adsorption Thermodynamics of HP-β-CDCP/Fe3O4 Nanocomposites

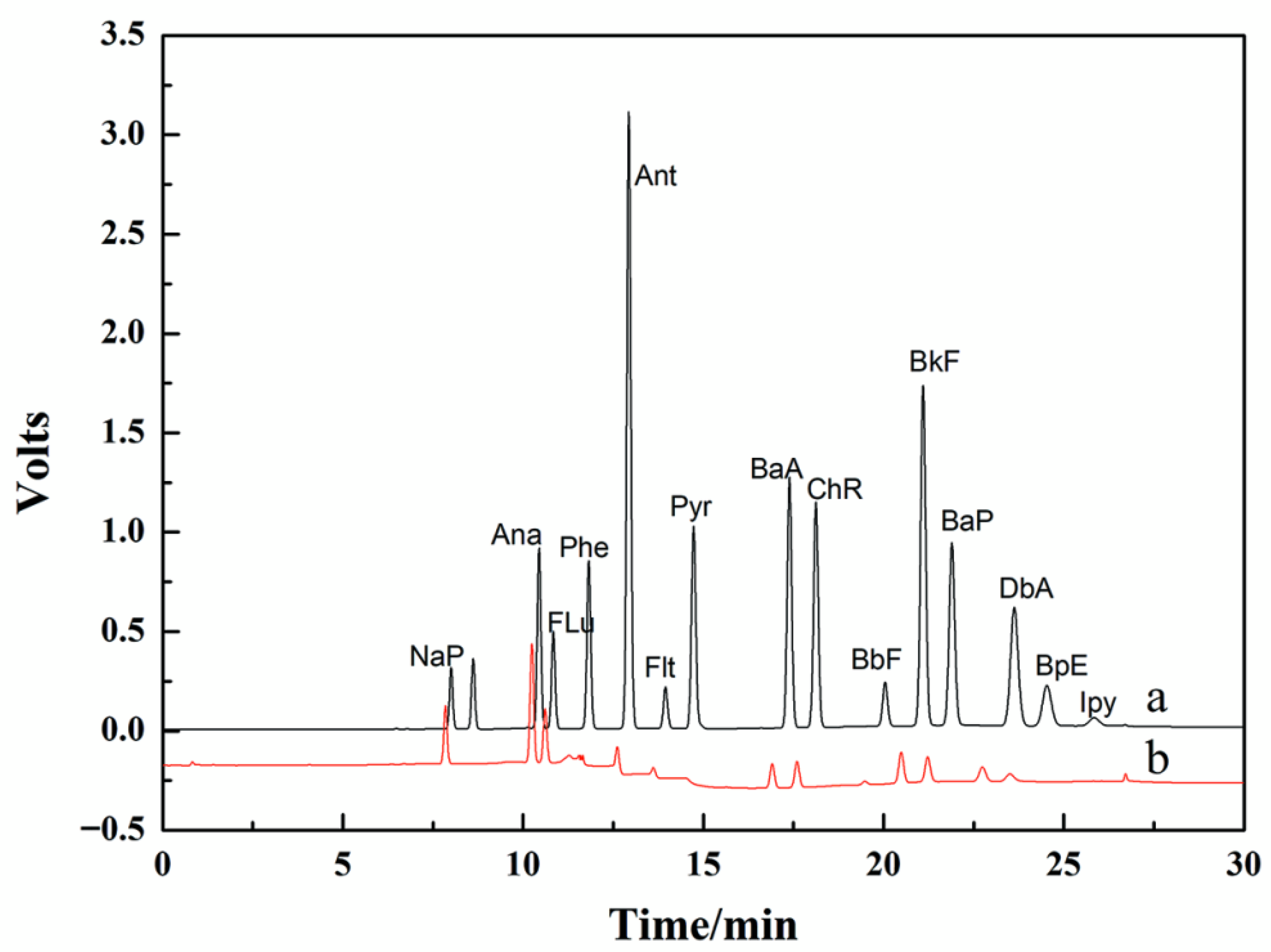

3.6. Analyses

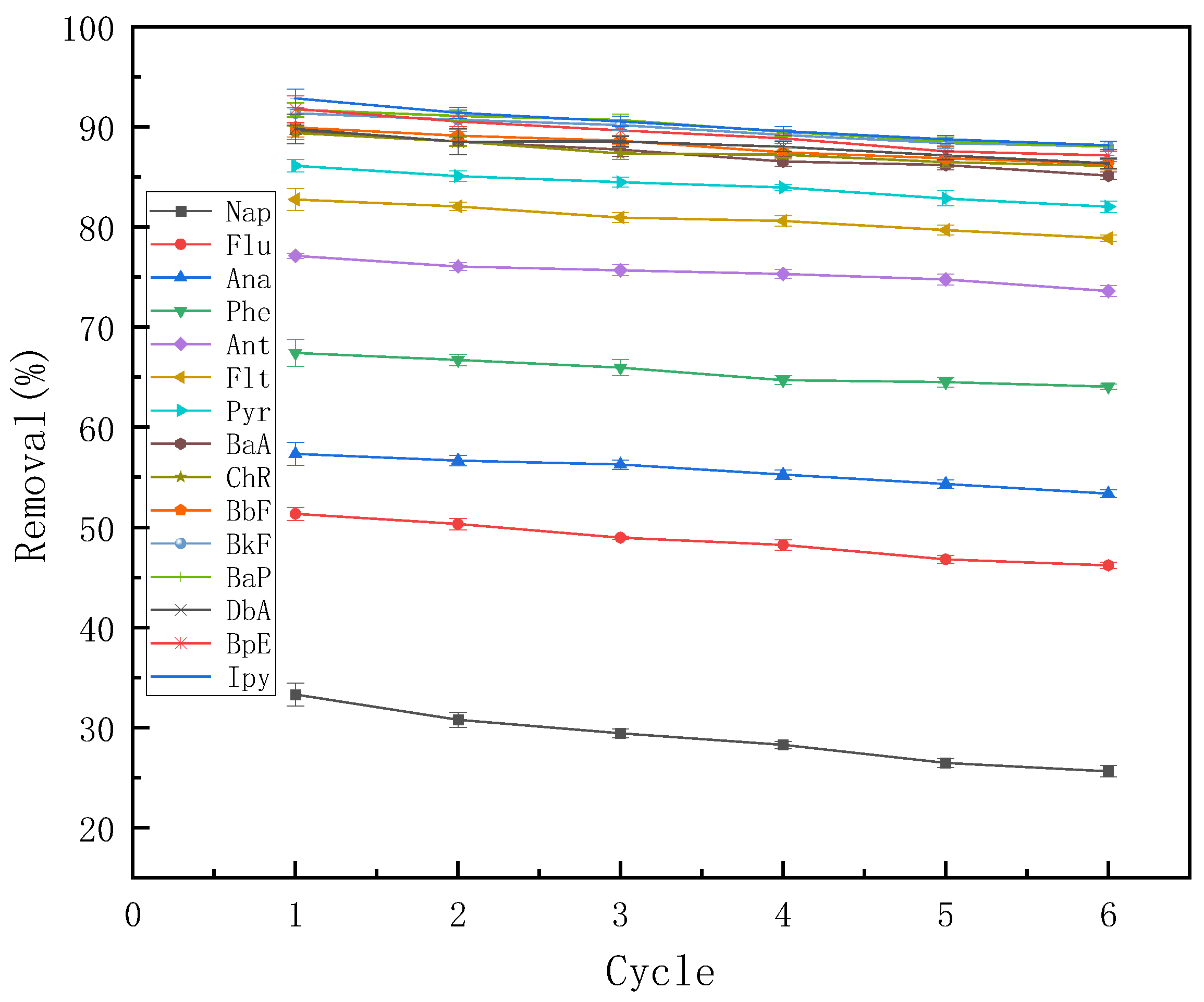

3.6.1. Regeneration and Reusability Study

3.6.2. Adsorption Capacity

3.6.3. Analysis of Simulated Wastewater

3.7. Comparative Study

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, L. Distribution Characteristics and Pollution Sources Analysis of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Phthalate Esters in the Seawater of Land-Based Outlets around Zhanjiang Bay in Spring. Water 2024, 16, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; Li, P.; Xia, S.; Huang, Q. Contamination of 16 priority polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in urban source water at the tidal reach of the Yangtze River. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 61222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Półtorak, A.; Onopiuk, A.; Kielar, J.; Chojnacki, J.; Najser, T.; Kukiełka, L.; Najser, J.; Mikeska, M.; Gaze, B.; Knutel, B.; et al. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Wheat Straw Pyrolysis Products Produced for Energy Purposes. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, Y.P. Long-term (1993–2018) particulate polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) concentration trend in the atmosphere of Seoul: Changes in major sources and health effects. Atmos. Environ. 2024, 325, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, H.A.; Alotaibi, K.D.; EL-Saeid, M.H.; Giesy, J.P. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) and Metals in Diverse Biochar Products: Effect of Feedstock Type and Pyrolysis Temperature. Toxics 2023, 11, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, M.; Tan, Z.; Zeng, X.; Liu, Z.; Liu, P.; Ali, A.; Qiu, H.; Jiang, W.; Qin, H. Contamination and Health Risk Assessment of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Seasoning Flour Products in Hunan, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, W.; Sun, J.; Wang, J.; Sun, H.Z.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, N.; Chen, Y.; Shen, G. Inhalation exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) bound to very fine particles (VFPs): A multi-provincial field investigation in China. Build. Environ. 2024, 261, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, A.A.; Oparinu, A.R.; Haleemat, A.T.; Oladapo, A.O. Sources, Toxicity, Health and Ecological Risks of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the Sediment of an Osogbo Tourist River. Soil Sediment Contam. 2022, 31, 669. [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi, M.; Aziz, R.; Rafiq, M.T. Efficient performance of InP and InP/ZnS quantum dots for photocatalytic degradation of toxic aquatic pollutants. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 19986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Dhau, J.; Kumar, R.; Badru, R.; Singh, P.; Mishra, Y.K.; Kaushik, A. Tailored carbon materials (TCM) for enhancing photocatalytic degradation of polyaromatic hydrocarbons. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2024, 144, 101289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Ru, J. Hierarchical porous MOFs@COFs-based molecular trap solid-phase microextraction for efficient capture of PAHs and adsorption mechanisms. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 328, 125041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, S.K.; Fung, Y.; Chan, H.Y.; Han, J.; Lo, C.M. A Mini-Review for an Adsorption of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) by Physical Gel. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2021, 6, 8195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, S.; Pant, K.K.; Kaushal, P. Modified Sugarcane leaf biochar for remediation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) from wastewater: Activation, optimization, mechanism. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2025, 30, 102113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Feng, S.; Zhang, J. The Adsorption and Regeneration of Magnetic Modified Bentonite Composite for Dye Wastewater. Key Eng. Mater. 2022, 905, 338. [Google Scholar]

- Tee, G.T.; Gok, X.Y.; Yong, W.F. Adsorption of pollutants in wastewater via biosorbents, nanoparticles and magnetic biosorbents: A review. Environ. Res. 2022, 212, 113248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.F.; Lu, X.; Huang, Y.; Liu, C.W.; Zhao, S.L. Fe3O4@ionic liquid@methyl orange nanoparticles as a novel nano-adsorbent for magnetic solid-phase extraction of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in environmental water samples. Talant 2014, 119, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, S.H.; Soleimani, M. Usage of magnetic activated carbon as a potential adsorbent for aniline adsorption from wastewater. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 4570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badruddoza, A.Z.M.; Shawon, Z.B.Z.; Daniel, T.W.J.; Hidajat, K.; Uddin, M.S. Fe3O4/cyclodextrin polymer nanocomposites for selective heavy metals removal from industrial wastewater. Carbohyd. Polym. 2013, 91, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.J.; Park, B.R.; Lee, B.H.; Cho, J.Y.; Park, B.S.; Kim, Y.M. A comparative study on the characteristics and properties of cyclodextrans, cyclodextrins, and their complexes with biologically active compounds. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 168, 111587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zhou, X.; Cheng, Q.; Liu, Y. Blue phosphorescent solid supramolecular assemblies between hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin and triazine derivatives for achieving multicolor delayed fluorescence. Nano Today 2025, 60, 102561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Sun, G. Hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin encapsulated stationary phase based on silica monolith particles for enantioseparation in liquid chromatography. J. Sep. Sci. 2020, 44, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, A.A.M.; Kumar, G.S.S.; Rajendiran, N.; Sathiyaseelan, K.; Balamathi, M. Interactions between Diphenylamine with 2-Hydroxypropyl β-Cyclodextrin based on Spectral, Biological and Theoretical Investigations. J. Macromol. Sci. Part B 2024, 63, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniyazagan, M.; Chakraborty, S.; Sánchez, H.P.; Stalin, T. Encapsulation of triclosan within 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin cavity and its application in the chemisorption of rhodamine B dye. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 282, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niki, J.; Watson, M.; Tubi, A.; Oli, M.; Agbaba, J. Recent trends in the application of magnetic nanocomposites for heavy metals removal from water: A review. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2024, 59, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, A.; Khan, F.S.A.; Mubarak, N.M.; Tan, Y.H.; Mazari, S.A. Magnetic nanocomposites for sustainable water purification—A comprehensive review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 19563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinu, A.; Miyahara, M.; Ariga, K. Biomaterial immobilization in nanoporous carbon molecular sieves: Influence of solution pH, pore volume, and pore diameter. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 6436–6441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.S. Preparation of Nitro/Amino-Functionalized Magnetic Covalent Organic Frame Adsorbents and Their Application in Bisphenol Analysis. Master’s Dissertation, Northwest University of China, Xi’ an, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Eeshwarasinghe, D.; Loganathan, P.; Vigneswaran, S. Simultaneous removal of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and heavy metals from water using granular activated carbon. Chemosphere 2019, 223, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, R.N.; Neves, T.D.F.; Silva, M.G.C.D.; Mastelaro, V.R.; Vieira, M.G.A.V.; Prediger, P. Comparative efficiency of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon removal by novel graphene oxide composites prepared from conventional and green synthesis. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 361, 132244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Li, J.; Ma, J.; Huang, G.X.; Yan, L.J. Adsorption performance of DNA magnetic nanoparticles to phenanthrene in Water. Chin. J. Environ. Eng. 2024, 18, 503. [Google Scholar]

- Wisniowska, E.; Wlodarczyk-Makula, M. Adsorption of selected 3- and 4-ring polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons on polyester microfibers preliminary studies. Desalin. Water Treat. 2021, 232, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topuz, F.; Uyar, T. Cyclodextrin-functionalized mesostructured silica nanoparticles for removal of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 497, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Time/Min | 0.00 | 0.66 | 20.0 | 25.0 | 27.0 | 30.0 | |

| Mobile Phase | |||||||

| Acetonitrile (%) | 40 | 40 | 100 | 100 | 40 | 40 | |

| Water (%) | 60 | 60 | 0 | 0 | 60 | 60 | |

| Time/Min | 0.0 | 11.5 | 12.5 | 13.5 | 14.5 | 19.0 | 25.2 | |

| Wavelength | ||||||||

| λex (nm) | 280 | 254 | 254 | 290 | 270 | 290 | 305 | |

| λem (nm) | 340 | 350 | 400 | 460 | 390 | 410 | 500 | |

| Model | Parameter | Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BaP | Ant | ||

| Pseudo-first order kinetic model | R2 | 0.9877 | 0.9801 |

| k1 | 0.237 | 0.195 | |

| Qe | 18.3 | 15.6 | |

| Pseudo-second order kinetic model | R2 | 0.9965 | 0.9929 |

| k2 | 0.015 | 0.070 | |

| Qe | 18.3 | 15.6 | |

| Analyst | Langmuir Model | Freundlich Model | Elovich Model | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qmax | KL | R2L | nF | KF | R2F | a | b | R2 | |

| (mg·g−1) | |||||||||

| Ant | 16.8 | 0.55 | 0.9747 | 1.17 | 12.75 | 0.9838 | 6.87 | 0.227 | 0.9564 |

| Bap | 19.2 | 0.21 | 0.9840 | 1.45 | 15.63 | 0.9903 | 10.9 | 0.208 | 0.9534 |

| Analyst | ΔHθ/ (kJ·mol−1) | ΔSθ/(J (mol·K)−1) | ΔGθ/(kJ·mol−1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 298.15 K | 308.15 K | 318.15 K | |||

| Ant | −5.76 | 1.83 | −6.29 | −6.37 | −6.32 |

| Bap | −5.35 | 4.42 | −6.67 | −6.70 | −6.76 |

| Compound | Molecular Formula | Molecular Weight | Correction Curve | R2 | Removal Efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NaP | C10H8 | 128.17 | y = 135.11x + 0.68 | 0.9999 | 33.9 |

| FLu | C13H10 | 166.22 | y = 231.56x + 0.97 | 0.9998 | 51.5 |

| Ana | C12H10 | 154.21 | y = 419.60x + 3.94 | 0.9997 | 58.5 |

| Phe | C14H10 | 178.23 | y = 411.59x + 3.36 | 0.9998 | 68.0 |

| Ant | C14H10 | 178.23 | y = 1555.9x + 12.11 | 1 | 77.3 |

| Flt | C16H10 | 202.25 | y = 115.4x + 0.40 | 1 | 83.2 |

| Pyr | C16H10 | 202.25 | y = 597.09x − 0.12 | 0.9998 | 86.3 |

| BaA | C18H12 | 228.29 | y = 737.14x − 0.10 | 0.9998 | 89.7 |

| ChR | C18H12 | 228.29 | y = 688.39x + 0.044 | 0.9998 | 89.6 |

| BbF | C22H12 | 252.31 | y = 139.27x + 0.84 | 1 | 90.1 |

| BkF | C22H12 | 252.31 | y = 1108x + 5.21 | 0.9999 | 91.8 |

| BaP | C20H12 | 252.3 | y = 1022.4x − 11.88 | 0.9998 | 91.9 |

| DbA | C22H14 | 278.35 | y = 602.19x − 1.48 | 0.9997 | 90.3 |

| BpE | C22H12 | 276.33 | y = 294.04x − 2.33 | 0.9991 | 92.1 |

| Ipy | C22H12 | 276.33 | y = 55.38x − 0.31 | 1 | 93.1 |

| Material | Pollutant | Adsorption Quantity (mg·g−1) | Removal Efficiency (%) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Granular activated carbon (GAC) | Ana, Phe | 2.63, 7.36 | - | [28] |

| G-mCS/GO | NaP, Ant, Flt | 11.9, 15.8, 15.4 | 93.6, 89.2, 62.3 | [29] |

| DNA magnetic nanoparticles | Phe | 0.220 | 88.0 | [30] |

| Polyester microfibers | 3- and 4-ring PAHs | 0.0250–1.42 | 62.0–88.0 | [31] |

| β-CD-MSNs | Pyr, Ant, Phe, Flu, Flt | 0.3–1.65 | - | [32] |

| HP-β-CDCP/Fe3O4 nanocomposites | Fifteen representative PAHs | 6.46–19.0 | 33.9–93.1 | This work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ping, W.; Yang, J.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, W.; Shi, Y.; Yang, Q. Hydroxypropyl-β-Cyclodextrin Improves Removal of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons by Fe3O4 Nanocomposites. Magnetochemistry 2026, 12, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/magnetochemistry12010004

Ping W, Yang J, Cheng X, Zhang W, Shi Y, Yang Q. Hydroxypropyl-β-Cyclodextrin Improves Removal of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons by Fe3O4 Nanocomposites. Magnetochemistry. 2026; 12(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/magnetochemistry12010004

Chicago/Turabian StylePing, Wenhui, Juan Yang, Xiaohong Cheng, Weibing Zhang, Yilan Shi, and Qinghua Yang. 2026. "Hydroxypropyl-β-Cyclodextrin Improves Removal of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons by Fe3O4 Nanocomposites" Magnetochemistry 12, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/magnetochemistry12010004

APA StylePing, W., Yang, J., Cheng, X., Zhang, W., Shi, Y., & Yang, Q. (2026). Hydroxypropyl-β-Cyclodextrin Improves Removal of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons by Fe3O4 Nanocomposites. Magnetochemistry, 12(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/magnetochemistry12010004