Elevated Oxygen Contributes to the Promotion of Polyphenol Biosynthesis and Antioxidant Capacity: A Case Study on Strawberries

Abstract

1. Introduction

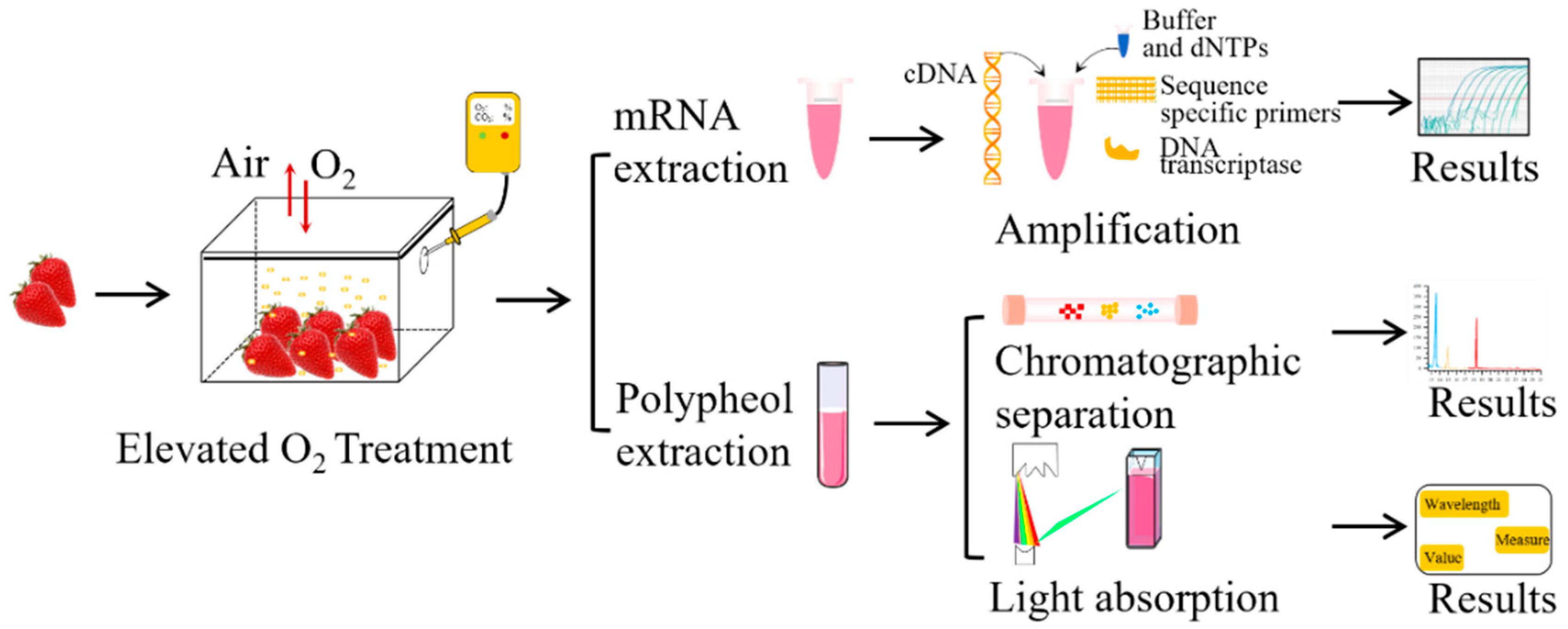

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strawberry Materials and Treatments

2.2. Determination of Polyphenols

2.2.1. Polyphenol Extraction

2.2.2. Polyphenol Concentrations

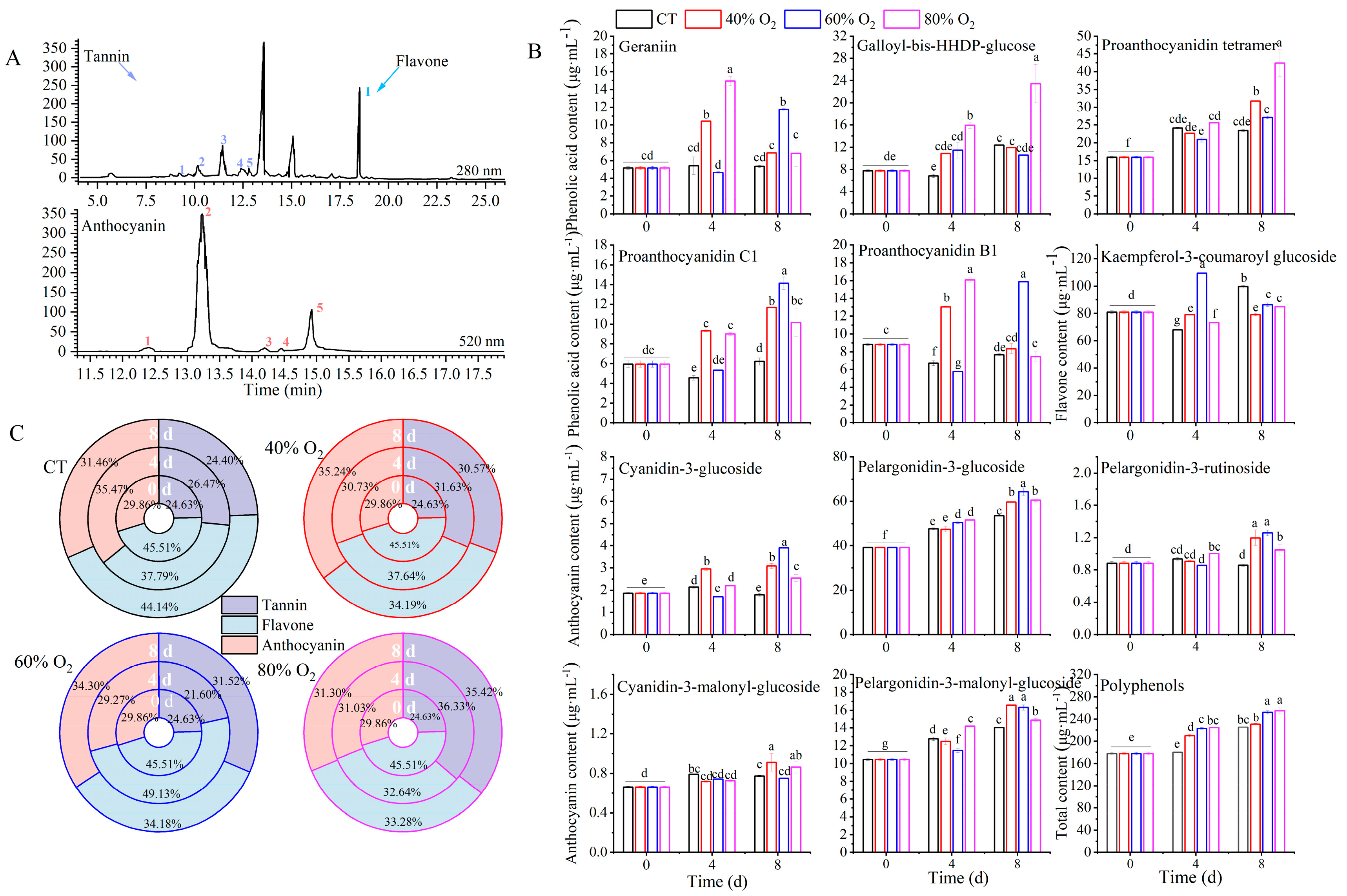

2.2.3. Identification of Individual Polyphenols

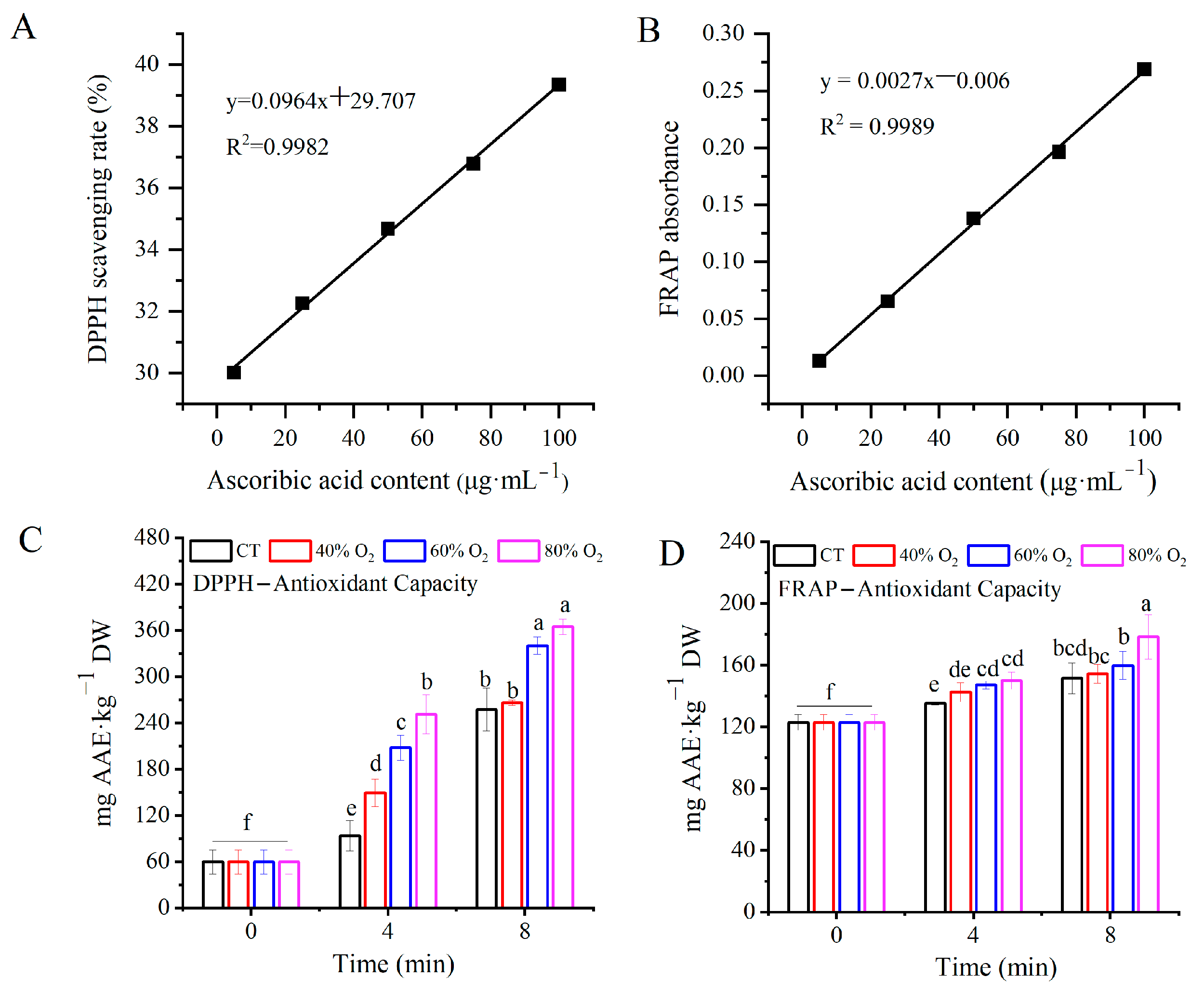

2.3. Determination of Antioxidant Capacity

2.3.1. DPPH Scavenging Capacity

2.3.2. FRAP

2.4. Real-Time Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) Assay

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

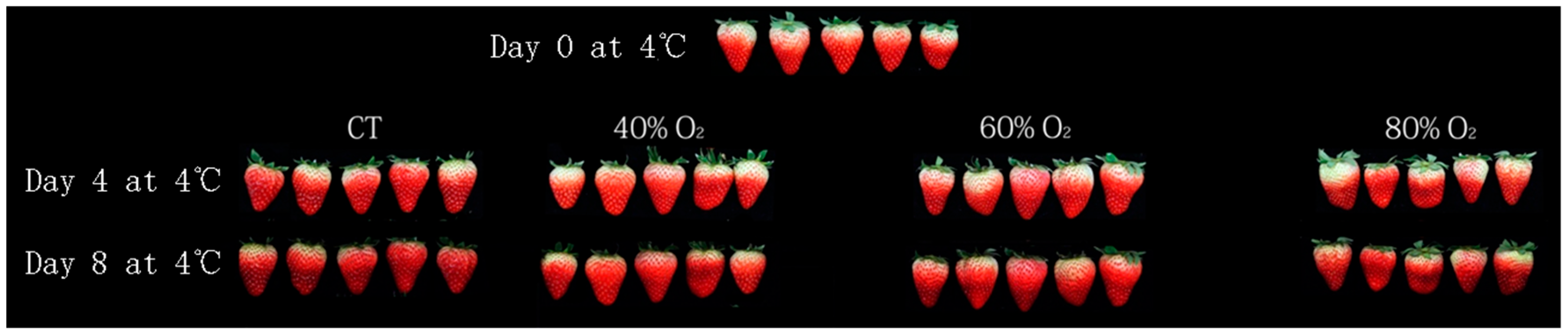

3.1. Appearance Quality

3.2. Individual Polyphenol Concentrations

3.3. Antioxidant Capacity

3.4. Gene Expression Involved in Polyphenol Pathway

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, J.X.; Mao, L.C.; Mi, H.B.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Ying, T.J.; Luo, Z.S. Detachment-accelerated ripening and senescence of strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch. cv. Akihime) fruit and the regulation role of multiple phytohormones. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2014, 36, 2441–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.M.; Joyce, D.C. ABA effects on ethylene production, PAL activity, anthocyanin and phenolic contents of strawberry fruit. Plant Growth Regul. 2003, 39, 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.; Abadias, M.; Usall, J.; Torres, R.; Teixidó, N.; Viñas, I. Application of modified atmosphere packaging as a safety approach to fresh-cut fruits and vegetables—A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 46, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Luo, Z.; Ban, Z.; Lu, H.; Li, D.; Yang, D.; Aghdam, M.S.; Li, L. The effect of the layer-by-layer (LBL) edible coating on strawberry quality and metabolites during storage. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2019, 147, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghdam, M.S.; Fard, J.R. Melatonin treatment attenuates postharvest decay and maintains nutritional quality of strawberry fruits (Fragaria × anannasa cv. Selva) by enhancing GABA shunt activity. Food Chem. 2017, 221, 1650–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, G.; Zhang, M.; Luo, G.; Peng, J.; Salokhe, V.M.; Guo, J. A Effect of modified atmosphere packaging on the preservation of strawberry and the extension of its shelf-life. Int. Agrophys. 2004, 18, 195–201. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Zhang, X.; Qu, H.; Li, L.; Mao, B.; Xu, Y.; Lin, X.; Luo, Z. Delaying the biosynthesis of aromatic secondary metabolites in postharvest strawberry fruit exposed to elevated CO2 atmosphere. Food Chem. 2020, 306, 125611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, C.; Fellman, J.K.; Rudell, D.R.; Mattheis, J. Scarlett Spur Red Delicious apple volatile production accompanying physiological disorder development during low pO2 controlled atmosphere storage. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 1741–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Mao, L.; Han, X.; Lu, W.; Xie, D.; Ren, X.; Zhao, Y. High oxygen facilitates wound induction of suberin polyphenolics in kiwifruit. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 2223–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.P.; Xu, X.Y.; Luo, Z.; Chen, Y.; Xu, Y.; Xiao, G. Effect of high O2 atmosphere packaging on postharvest quality of purple passion fruit (Passiflora edulis Sims). J. Food Process. Preserv. 2018, 42, e13749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinu, M.G.; Dore, A.; Palma, A.; D’Aquino, S.; Azara, E.; Rodov, V.; D’hallewin, G. Effect of superatmospheric oxygen storage on the content of phytonutrients in ‘Sanguinello Comune’ blood orange. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2016, 112, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Tong, W.; Liu, G.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Huang, G.; Wei, L. Effect of high oxygen treatment on the respiratory rate and preservation of mulberry. Sci. Technol. Food Ind. 2015, 36, 306–309, 314. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, H.; Wang, K.; Wang, L.; Li, D.; Yan, J.; Ban, Z.; Luo, Z.; Li, L.; Yang, D. Effect of superatmospheric oxygen exposure on strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch.) volatiles, sensory and chemical attributes. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2018, 142, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodelón, O.G.; Blanch, M.; Sanchez-Ballesta, M.T.; Escribano, M.I.; Merodio, C. The effects of high CO2 levels on anthocyanin composition, antioxidant activity and soluble sugar content of strawberries stored at low non-freezing temperature. Food Chem. 2010, 122, 673–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, R.; Jaramillo, S.; Rodriguez, G.; Espejo, J.A.; Guillen, R.; Fernandez-Bolanos, J.; Heredia, A.; Jimenez, A. Antioxidant activity of ethanolic extracts from several asparagus cultivars. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 5212–5217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benzie, I.F.F.; Strain, J.J. The Ferric Reducing Ability of Plasma (FRAP) as a Measure of “Antioxidant Power”: The FRAP Assay. Anal. Biochem. 1996, 239, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Luo, Z.; Yang, M.; Li, D.; Qi, M.; Xu, Y.; Abdelshafy, A.M.; Ban, Z.; Wang, F.; Li, L. Role of exogenous melatonin in table grapes: First evidence on contribution to the phenolics-oriented response. Food Chem. 2020, 329, 127155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, M.; Del Bo, C.; Tucci, M.; Klimis-Zacas, D.; Riso, P.; Porrini, M. Modulation of Adhesion Process, E-Selectin and VEGF Production by Anthocyanins and Their Metabolites in an in vitro Model of Atherosclerosis. Nutrients 2020, 12, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; Gao, W.; You, C.; Wang, X.; et al. Cellulose Nanofibers Extracted from Natural Wood Improve the Postharvest Appearance Quality of Apples. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 881783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, C.Y.; Wang, S.Y.; Zheng, W. Effect of high-oxygen atmospheres on blueberry phenolics, anthocyanins, and antioxidant capacity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 7162–7169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hébert, C.; Charles, M.T.; Gauthier, L.; Willemot, C.; Khanizadeh, S.; Cousineau, J. Strawberry Proanthocyanidins: Biochemical Markers for Botrytis Cinerea Resistance and Shelf-Life Predictability. Acta Hortic. 2002, 567, 659–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes-Hernandez, T.Y.; Gasparrini, M.; Afrin, S.; Bompadre, S.; Mezzetti, B.; Quiles, J.L.; Giampieri, F.; Battino, M. The Healthy Effects of Strawberry Polyphenols: Which Strategy behind Antioxidant Capacity? Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 56 (Suppl. S1), S46–S59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skrovankova, S.; Sumczynski, D.; Mlcek, J.; Jurikova, T.; Sochor, J. Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Activity in Different Types of Berries. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 24673–24706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fadda, A.; Palma, A.; D’Aquino, S.; Mulas, M. Effects of Myrtle (Myrtus communis L.) Fruit Cold Storage Under Modified Atmosphere on Liqueur Quality. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2017, 41, e12776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Ban, Z.; Luo, Z.; Li, J.; Lu, H.; Li, D.; Chen, C.; Li, L. Impact of elevated O2 and CO2 atmospheres on chemical attributes and quality of strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch.) during storage. Food Chem. 2020, 307, 125550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala-Zavala, J.F.; Wang, S.Y.; Wang, C.Y.; Gonzalez-Aguilar, G.A. High oxygen treatment increases antioxidant capacity and postharvest life of strawberry fruit. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2007, 45, 166–173. [Google Scholar]

- Odriozola-Serrano, I.; Soliva-Fortuny, R.; Martín-Belloso, O. Changes in bioactive composition of fresh-cut strawberries stored under superatmospheric oxygen, low-oxygen or passive atmospheres. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2010, 23, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocci, E.; Rocculi, P.; Romani, S.; Rosa, M.D. Changes in nutritional properties of minimally processed apples during storage. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2006, 39, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oms-Oliu, G.; Odriozola-Serrano, I.; Soliva-Fortuny, R.; Martín-Belloso, O. Antioxidant Content of Fresh-Cut Pears Stored in High-O2 Active Packages Compared with Conventional Low-O2 Active and Passive Modified Atmosphere Packaging. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 932–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchiosi, R.; Dos Santos, W.D.; Constantin, R.P.; de Lima, R.B.; Soares, A.R.; Finger-Teixeira, A.; Mota, T.R.; de Oliveira, D.M.; de Paiva Foletto-Felipe, M.; Abrahão, J.; et al. Biosynthesis and metabolic actions of simple phenolic acids in plants. Phytochem. Rev. 2020, 19, 865–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiorcea-Paquim, A.M.; Enache, T.A.; De Souza Gil, E.; Oliveira-Brett, A.M. Natural phenolic antioxidants electrochemistry: Towards a new food science methodology. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 1680–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amorati, R.; Valgimigli, L. Advantages and limitations of common testing methods for antioxidants. Free Radic. Res. 2015, 49, 633–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutteridge, J.M.; Halliwell, B. Antioxidants: Molecules, medicines, and myths. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 393, 561–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prempree, P.; Setha, S.; Pranamornkith, T. High oxygen pre-treatment affects quality and antioxidant capacity of strawberry (Fragaria x ananassa Duch.) during cold storage. Int. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2022, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, N.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, T.; Yang, H.; Peng, Q. Study on fermentation kinetics, antioxidant activity and flavor characteristics of Lactobacillus plantarum CCFM1050 fermented wolfberry pulp. Food Innov. Adv. 2024, 3, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, M.; Xiao, R.; Chen, J.-Y.; Lin, H.-T.; Duan, X.-W.; Jiang, Y.-M.; Lu, W.-J. Expression of a phenylalanine ammonia-lyase gene in relation to aril breakdown in harvested longan fruit. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2015, 84, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemzadeh, A.; Nasiri, A.; Jaafar, H.Z.; Baghdadi, A.; Ahmad, I. Changes in phytochemical synthesis, chalcone synthase activity and pharmaceutical qualities of sabah snake grass (Clinacanthus nutans L.) in relation to plant age. Molecules 2014, 19, 17632–17648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, K.M.; Schwinn, K.E.; Deroles, S.C.; Manson, D.G.; Lewis, D.H.; Bloor, S.J.; Bradley, J.M. Enhancing anthocyanin production by altering competition for substrate between flavonol synthase and dihydroflavonol 4-reductase. Euphytica 2003, 131, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metsämuuronen, S.; Sirén, H. Bioactive phenolic compounds, metabolism and properties: A review on valuable chemical compounds in Scots pine and Norway spruce. Phytochem. Rev. 2019, 18, 623–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

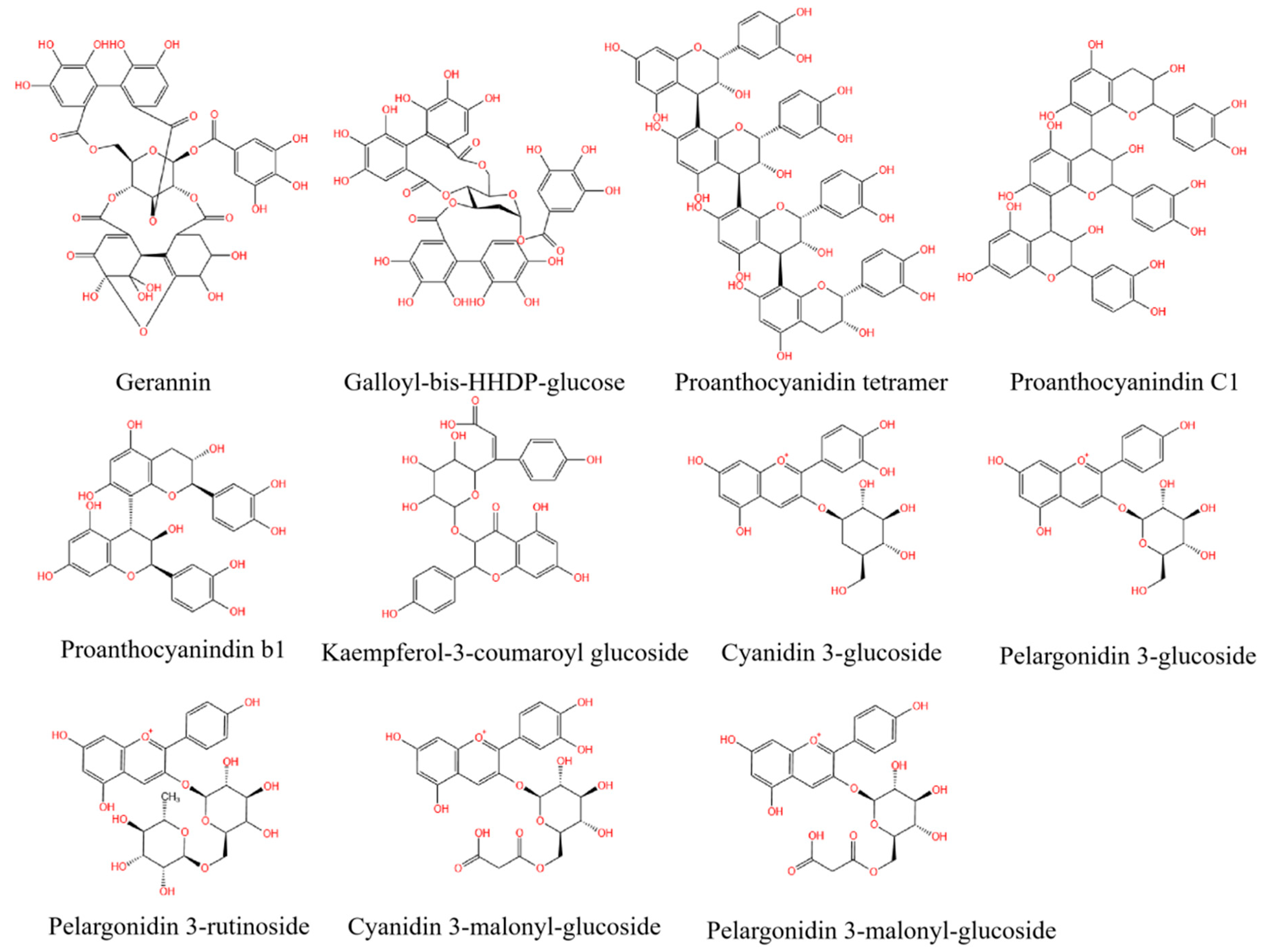

| No. | Retention Time | Molecular Ion [M+] (m/z) | Main Fragment (m/z) | Components | Classification | Wavelength |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9.877 | 951 | 907 and 783 | Geranin | Tannin | 280 nm |

| 2 | 10.231 | 938 | 783 and 509 | Galloyl-bis-HHDP-glucose | Tannin | 280 nm |

| 3 | 11.439 | 1153 | 983, 865, 577, 407, and 287 | Proanthocyanidin tetramer | Tannin | 280 nm |

| 4 | 12.383 | 865 | 740, 696, 577, 407, and 287 | Proanthocyanidin C1 | Tannin | 280 nm |

| 5 | 12.755 | 561 | 431, 407, and 269 | Proanthocyanidin B1 | Tannin | 280 nm |

| 1 | 18.437 | 593 | 447 and 285 | Kaempferol-3-coumaroyl glucoside | Flavone | 280 nm |

| 1 | 12.384 | 449 | 287 | Cyanidin 3-glucoside | Anthocyanin | 520 nm |

| 2 | 13.181 | 433 | 271 | Pelargonidin 3-glucoside | Anthocyanin | 520 nm |

| 3 | 14.162 | 579 | 271 and 433 | Pelargonidin 3-rutinoside | Anthocyanin | 520 nm |

| 4 | 14.452 | 535 | 287 | Cyanidin 3-malonyl-glucoside | Anthocyanin | 520 nm |

| 5 | 14.976 | 519 | 271 | Pelargonidin 3-malonyl-glucoside | Anthocyanin | 520 nm |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dong, Y.; Pang, L.; Mao, M.; Zhou, J.; Hu, Q.; Xiang, Y.; Li, L. Elevated Oxygen Contributes to the Promotion of Polyphenol Biosynthesis and Antioxidant Capacity: A Case Study on Strawberries. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11010107

Dong Y, Pang L, Mao M, Zhou J, Hu Q, Xiang Y, Li L. Elevated Oxygen Contributes to the Promotion of Polyphenol Biosynthesis and Antioxidant Capacity: A Case Study on Strawberries. Horticulturae. 2025; 11(1):107. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11010107

Chicago/Turabian StyleDong, Yingying, Lingling Pang, Mengfei Mao, Jingjing Zhou, Qiannan Hu, Yizhou Xiang, and Li Li. 2025. "Elevated Oxygen Contributes to the Promotion of Polyphenol Biosynthesis and Antioxidant Capacity: A Case Study on Strawberries" Horticulturae 11, no. 1: 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11010107

APA StyleDong, Y., Pang, L., Mao, M., Zhou, J., Hu, Q., Xiang, Y., & Li, L. (2025). Elevated Oxygen Contributes to the Promotion of Polyphenol Biosynthesis and Antioxidant Capacity: A Case Study on Strawberries. Horticulturae, 11(1), 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11010107