1. Introduction

Recent advances of manufacturing technologies have made metal foams commercially available [

1,

2,

3]. Naturally, they acquire high specific surface, high thermal conductivity and comparatively high permeability. Thus, metal foams are great candidates for efficient heat exchangers because they possess high interstitial heat transfer between the metal and passing fluid, while a pressure drop is only moderate due to a high permeability.

On the other hand, nanofluids, namely, fluids containing thermally conducting submicron solid particles, are known to have great potential as a high-energy carrier. Larger-sized particles cause numerous problems such as abrasion, clogging and high pressure loss, whereas these nanoparticles such as titania, alumina and copper oxide can stably be suspended within the fluids without causing settling out of suspension. A number of investigations on nanofluids were carried out for the past decade, in order to study their great potential as a high-energy carrier as well as their promising feature of high effective thermal conductivity (e.g., [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]). Thus, combination of metal foams and nanofluids, namely, nanofluid saturated metal foams may bring us to a new generation of high performance heat exchangers.

A set of volume averaged transport equations appropriate for convection in nanofluid saturated metal foams was obtained by Sakai

et al. [

11], on the assumption that local thermal equilibrium holds between fluid and metal phases, in which the volume averaged fluid temperature is assumed equal to that of metal temperature. In reality, the local thermal equilibrium assumption may fail, because the thermal conductivity of metal conducting heat from the wall is much higher than that of nanofluid.

Kuwahara

et al. [

12] carried out an elegant analysis to obtain a set of exact solutions for the case of forced convection in a channel filled with a fluid saturated metal foam. They demonstrated that forced convection in a channel subject to constant wall heat flux must be treated using a thermal non-equilibrium model, for the fluid and solid phases within the channel are never at thermal equilibrium. Yang

et al. [

13] faithfully followed their work, and compared the set of exact solutions based on local thermal equilibrium against that based on local thermal non-equilibrium models for the case of tube flows. Eventually, they concluded that substantial errors result from the assumption of local thermal equilibrium for the case of constant heat flux.

These theoretical investigations reveal that the local thermal equilibrium assumption is not valid within in a metal foam and a local thermal non-equilibrium model must be introduced with an interstitial heat transfer model between nanofluid and metal phases.

Yang and Nakayama [

14] and Yang

et al. [

15] pointed out another important feature associated with mechanical mixing within the metal foam, namely, dispersion. The mechanical mixing in heat transfer resulting from porous matrices is termed as thermal dispersion, whereas, in this study, mechanical dispersion in nanoparticles transport is referred to as “nanoparticle mechanical dispersion”,

i.e., macroscopic dispersion resulting from porous matrices (It should not be confused with “nanoparticle dispersion” meaning particles dispersed in the base fluid,

i.e., microscopic dispersion).

In what follows, an appropriate set of volume averaged transport equations for convection in nanofluid saturated metal foams is derived, exploiting a volume averaging theory [

16], and allowing that nanofluid temperature and metal temperature differ from each other,

i.e., local thermal non-equilibrium model. Microscopic transport equations, which are based on the Buongiorno model [

17] for convective heat transfer in nanofluids, are modified so as to account for the effects of nanoparticle volume fraction distributions on the conservation equations of continuity, momentum and energy. Subsequently, they are integrated within a local averaging volume, to obtain an appropriate set of governing equations in terms of volume averaged dependent variables [

18,

19,

20,

21]. The various terms associated with interfacial surface integrals [

22] and spatial correlations of spatial deviations are subsequently modeled mathematically using the volume averaged dependent variables.

A microscopic analysis (i.e., pore scale analysis) will also be conducted in order to investigate possible functional forms for describing longitudinal and transverse and thermal dispersion components in a nanofluid saturated metal foam. Furthermore, nanoparticle mechanical dispersion (i.e., macroscopic dispersion resulting from porous matrices) will be treated microscopically for the first time, and will be modeled mathematically, considering a pore scale conduit. The analysis reveals that the longitudinal particle mechanical dispersion works either to suppress or to enhance effective diffusion. It depends on the sign of the local phase temperature difference. The transverse counterpart, on the other hand, turns out to be insignificant and therefore can be neglected. Moreover, heat transfer performance evaluation under equal pumping power has been made for the case of forced convective heat transfer in a nanofluid saturated metal foam. The present study reveals that an unconventionally high level of the heat transfer rate (about 80 times more than the case of base fluid convection without a metal foam) is possible by combining metal foam with nanofluid.

2. Modified Buongiorno Equations for Nanofluids

Buongiorno [

17] carried out a magnitude analysis on the transport equations, assuming dilute mixture, incompressible flow, no chemical reactions, negligible viscous dissipation, negligible external forces, negligible radiative heat transfer, and local thermal equilibrium between nanoparticles and base fluid. Obviously, local thermal equilibrium holds between the nanoparticles and the base fluid, because the size of nanoparticles is so small that nanoparticle temperature changes in an instant to be at thermal equilibrium with that of surrounding base fluid. As demonstrated by Yang

et al. [

23], the two-component mixture model proposed by Buongiorno may be modified to account for nanofluid density variation in mass, momentum and energy conservations as

where ρ,

c, μ and

k are the density, heat capacity, viscosity and thermal conductivity of nanofluid, respectively, which depend on the nanoparticle volume fraction

φ as,

Brownian and thermophoretic diffusion coefficients are given by

and

respectively. Nanofluid thermophysical properties such as μ and

k are considered as given functions of

φ. Equation (5c,d) proposed by Maiga

et al. [

24] are believed to be the most reliable correlations, where the subscripts,

p and

bf refer to as nanoparticle and base fluid, respectively. Moreover,

kBO is the Boltzmann constant and

dp is the nanoparticle diameter.

dp can be anywhere of the order of 1 nm to 100 nm. Li and Nakayama [

25] investigated the effect of temperature-dependent thermophysical properties on convective heat transfer rates, and found that variations of base fluid properties due to temperature variation are small enough to be neglected as compared with those effects of nanoparticle volume fraction and temperature. Aladag

et al. [

26] pointed out that nanofluids with high particle volume fraction or within the range of low temperature may deviate from Newtonian characteristics. Therefore, we shall not consider the nanofluids of very high volume fraction or of very low temperature. Detailed discussions on these effects on the thermophysical properties may be found in Corcione [

27].

A number of investigators, including Bianco

et al. [

28], concluded that the two-component mixture model is quite capable of describing the nanofluid heat transfer, supporting the Buongiorno magnitudes analysis [

17]. It is interesting to note that the energy Equation (3) is identical to that of a pure fluid, except that all properties are functions of

φ. Naturally, nanoparticle conservation Equation (4) must be solved simultaneously with Equations (1) to (3) for the other dependent variables, since thermophysical properties strongly depend on spatial distribution of

φ. In some previous analyses, the spatial variations of thermophysical properties including Brownian and thermophoretic diffusion coefficients are neglected for simplicity. As discussed in Yang

et al. [

23], however, such analytical treatments result in substantial errors. Thus, in this study, all these variations will be considered.

Some investigators proposed dynamical models accounting for the effect of nanoparticle random motion on the effective thermal conductivity. However, as pointed out by Kleinstreuer and Feng [

29], such explicit modifications on the thermal conductivity are still being debated. This study is unique in the sense that the spatial distribution of the nanoparticle volume fraction is determined by solving the nanoparticle transport equation, and substituted into the empirical formulas as functions of nanoparticle volume fraction to evaluate the local values of the thermal properties.

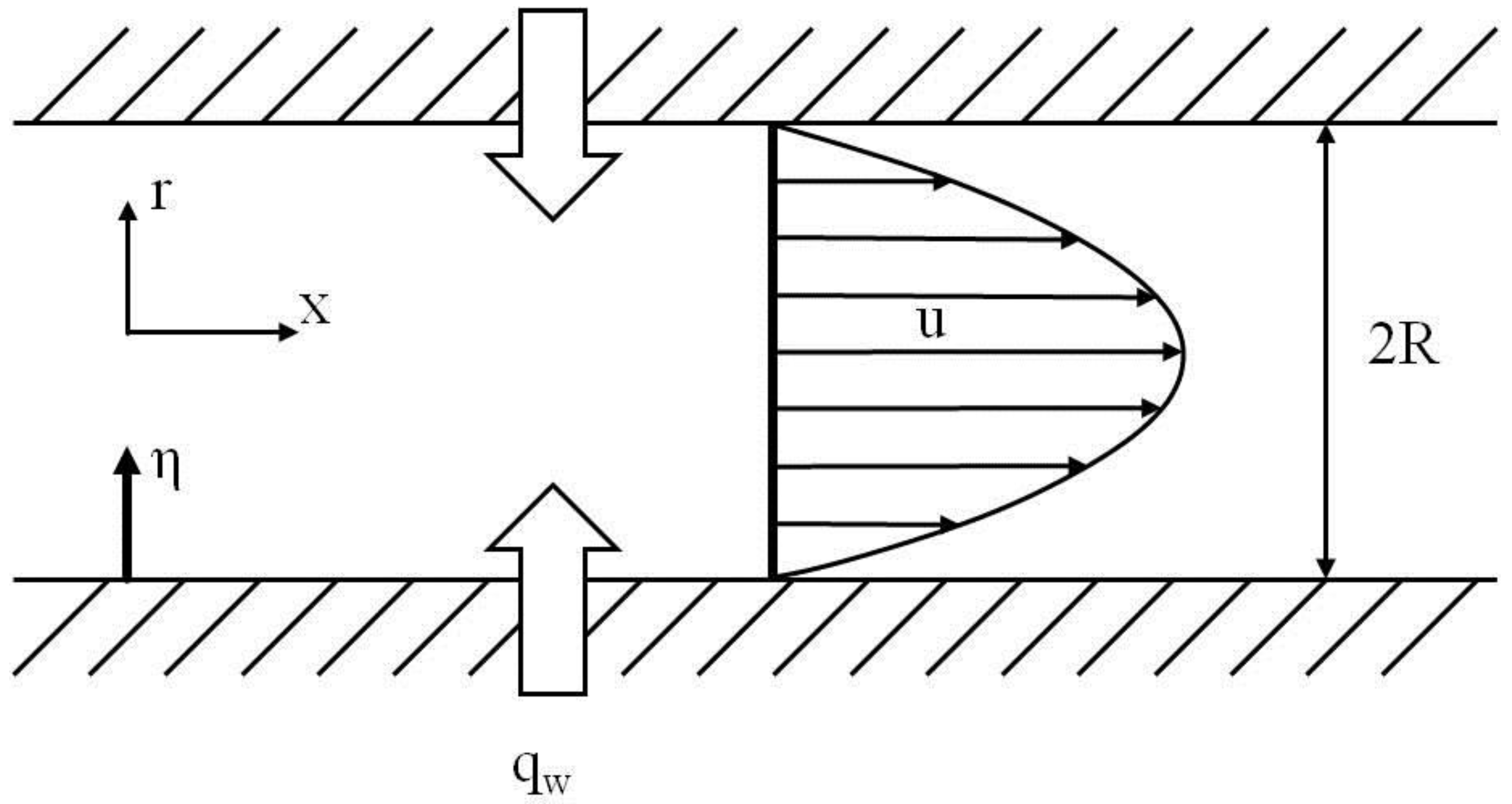

3. Clear Nanofluid Convective Flow in a Circular Tube

Before treating the cases of nanofluid saturated metal foam, we shall consider the fundamental case of clear nanofluid convective flow (

i.e., without a metal foam), namely, hydrodynamically and thermally fully developed flow in a tube subject to constant heat flux. The problem may be descried mathematically by writing the governing equations in the cylindrical coordinates (

x,

r) shown in

Figure 1 as

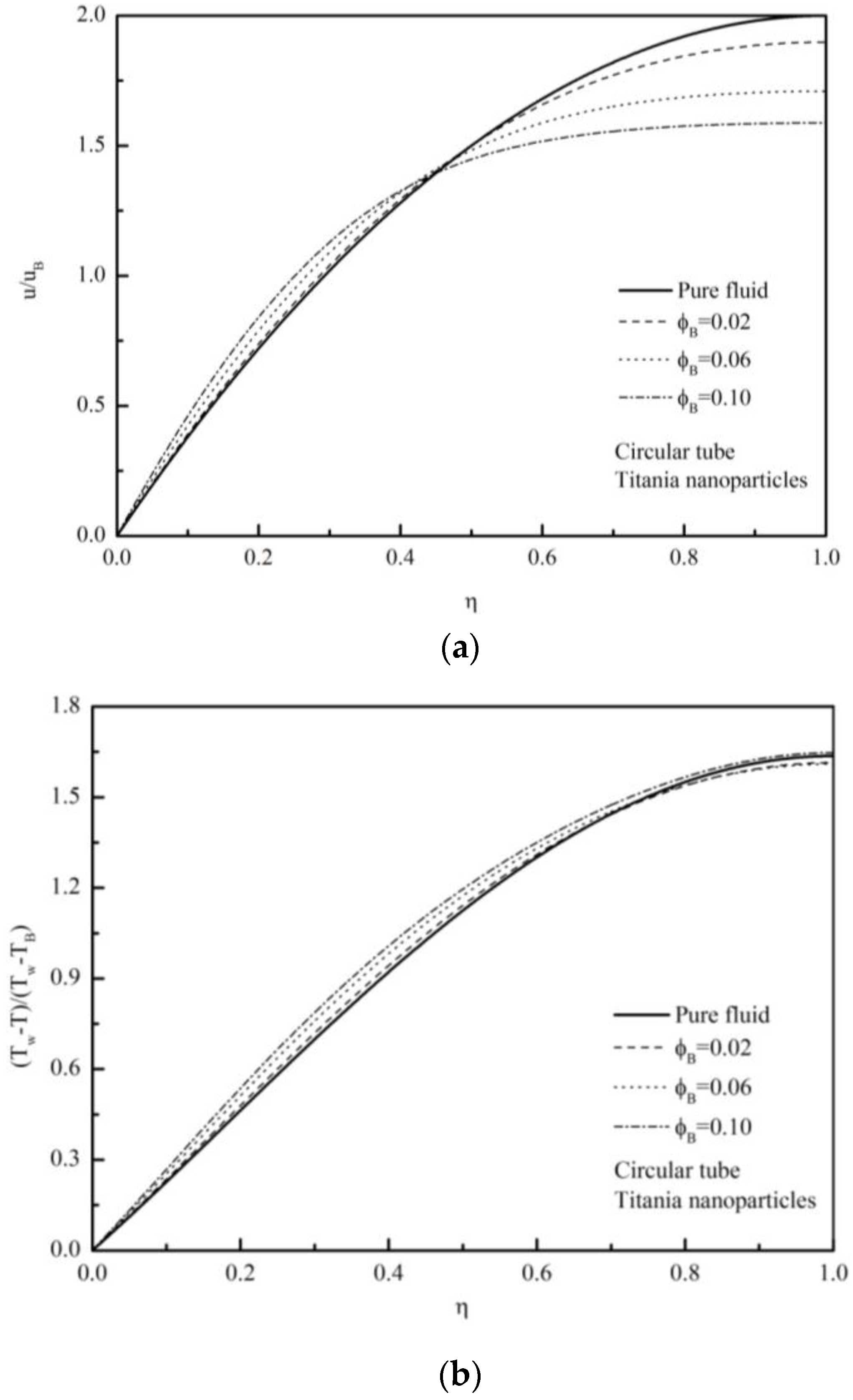

Yang

et al. [

23] transformed the preceding equations into the set of ordinary differential equations. This set of ordinary differential equations were integrated by using a versatile software SOLODE based on the Runge–Kutta–Gill method [

21]. The effects of the bulk mean particle volume fraction

on the velocity profile

are shown in

Figure 2a for the case of titania–water nanofluids in a tube with

= 0.2 and

= 0. Likewise, the temperature profiles are presented in

Figure 2b in terms of

. Furthermore, the distributions of the particle volume fraction

are shown in

Figure 2c. The figure indicates low volume fraction of particles near the wall and high volume fraction of particles in the core. This uneven distribution of the volume fraction of particles is caused by the thermopheresis, which drives the particles from the high temperature region near the wall to the low temperature region in the core. The unevenness grows further as the thermopheretic diffusion dominates over the Brownian diffusion. Due to low and high volume fractions of nanoparticles, the viscosity near the wall surface, as given by Equation (5c), is much smaller than that in the core. This results in the increase in the velocity near the wall and the decrease in the velocity in the core, as can be confirmed in

Figure 2a. This tendency is amplified as adding more particles.

Figure 2b consistently shows that the increase in the dimensionless velocity near the wall leads to a steeper dimensionless temperature gradient as compared with the one with pure fluids (

). The effects of

on these profiles are found be almost negligible, as varying

from 0 to 0.1. Therefore, all calculations have been carried out with

= 0.

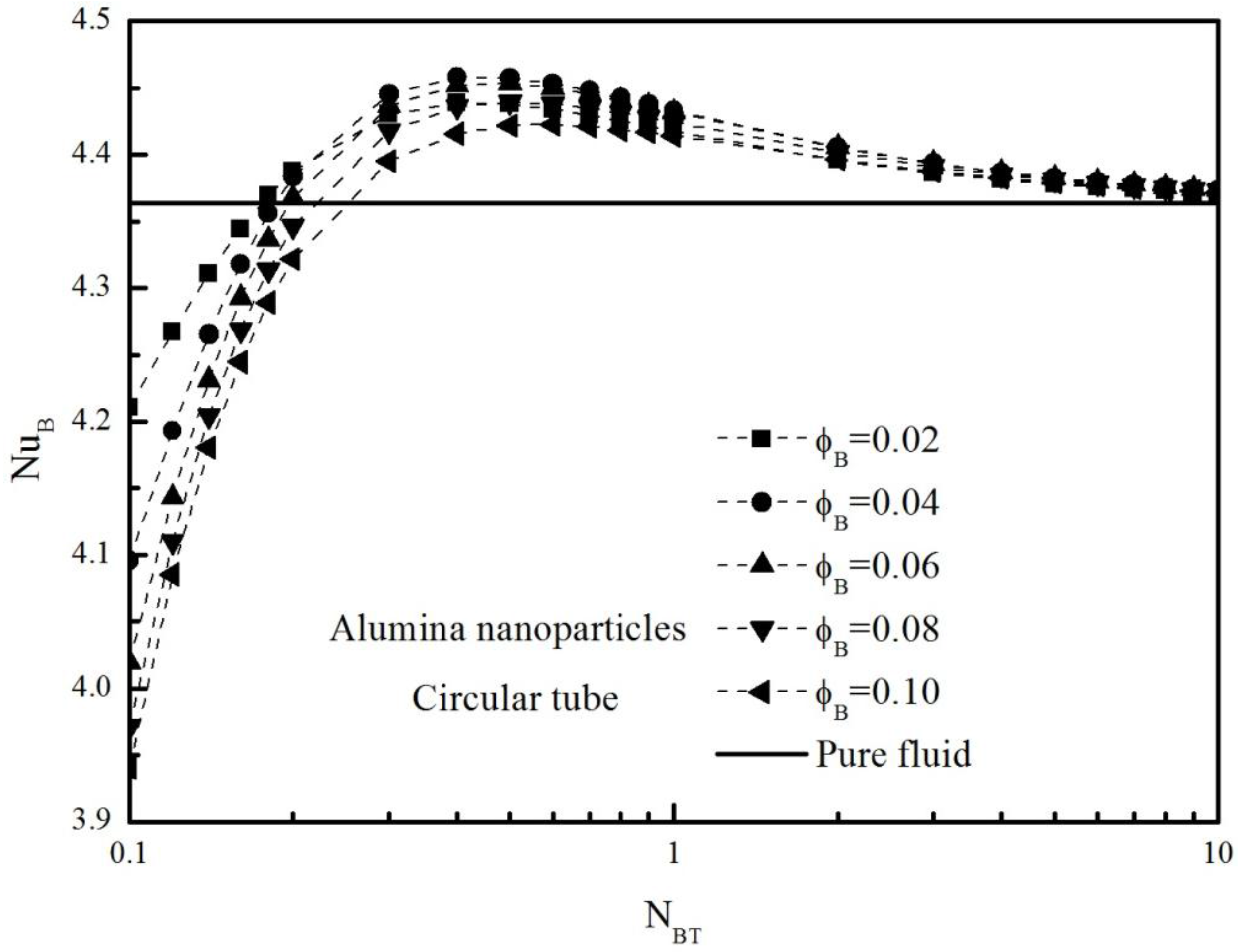

The Nusselt number based on the diameter

and the nanofluid bulk thermal conductivity

is given by

The Nusselt number is expressed in terms of the product of the Nusselt number based on the thermal conductivity at the wall and the thermal conductivity ratio . This thermal conductivity ratio is always less than 1. Hence, the anomalous heat transfer enhancement, in which the heat transfer coefficient exceeds the level expected from the increase in the effective thermal properties of nanofluids, is possible only when the Nusselt number is high enough to make its product (i.e., ) more than that of pure fluid, namely, 4.36.

for the case of alumina nanoparticles is shown in

Figure 3, which the anomalous heat transfer enhancement can be seen clearly. Such heat transfer anomaly is absent for the case of channel flow. This difference observed in the heat transfer characteristic may be attributed to the geometrical (radial) effects, namely, that events taking place near the peripheral walls, such as velocity and temperature changes, reflect on bulk quantities more in a tube than in a channel. The maximum value of

is achieved at

as shown in

Figure 3.

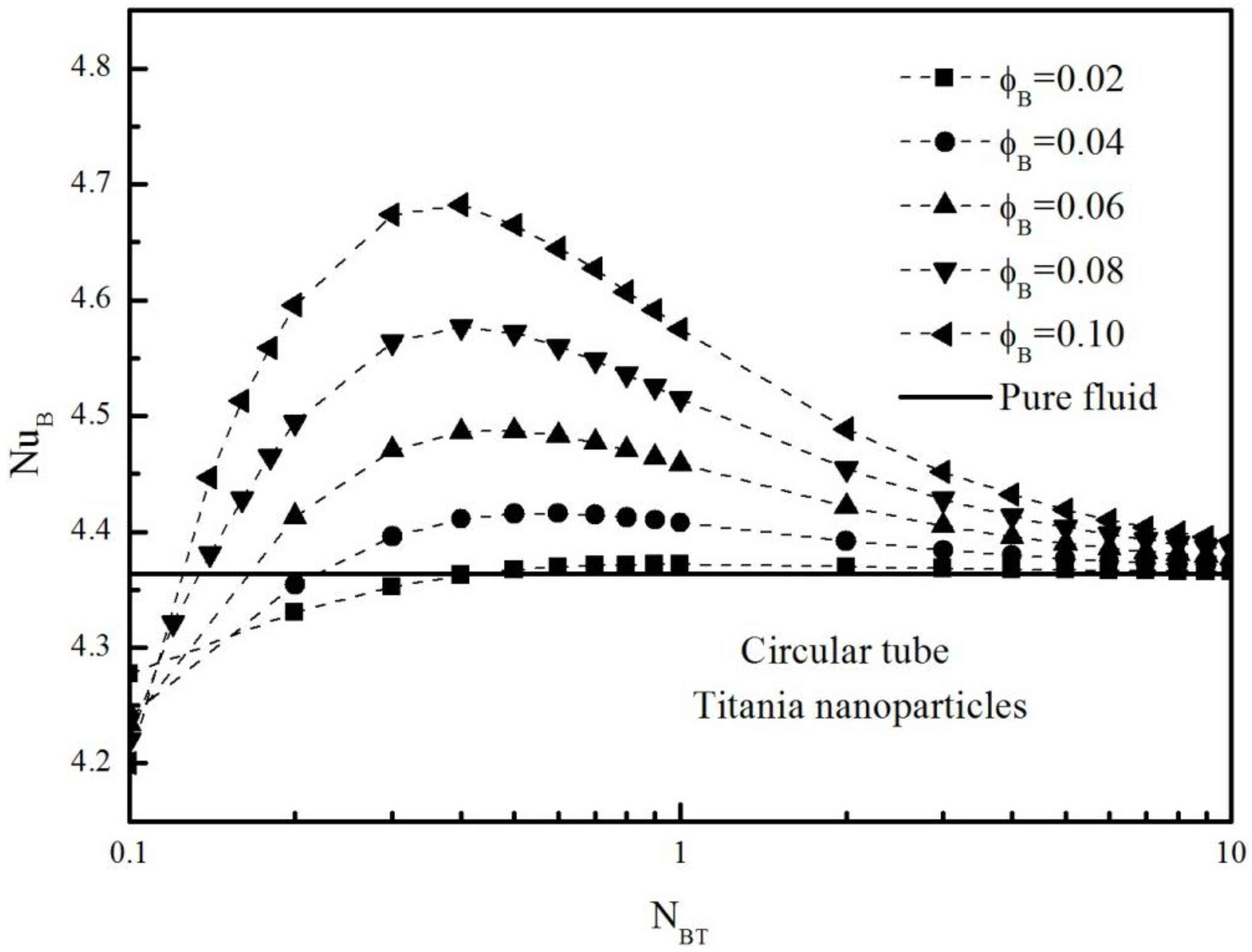

Figure 4 clearly shows that the degree of the anomalous heat transfer enhancement in titania–water nanofluids is higher than in alumina–water nanofluids. However, as in

Figure 5, the heat transfer coefficient of the alumina–water nanofluids is much higher than that of the titania–water nanofluids. This is simply due to the difference in

.

The analysis based on the Buongiorno model equations for convective heat transfer in clear nanofluid flows clearly indicates possible anomalous convective heat transfer enhancement. To be precise, the anomalous heat transfer enhancement has been captured theoretically for various cases of clear nanofluid flows, namely, the cases of titania–water nanofluids in a channel, alumina–water nanofluids in a tube and also titania–water nanofluids in a tube. Comparatively low volume fraction of particles near the wall is responsible for the anomalous heat transfer, because it yields a relatively low viscosity field there, hence, leading to high velocity and steep temperature gradient, near the wall. The maximum Nusselt number based on the bulk mean nanofluid thermal conductivity is observed around at . This finding may be utilized for designing nanoparticles in view of heat transfer enhancement. Moreover, the heat transfer coefficient for the case of alumina–water nanofluids in a tube is seen almost twice higher than that of water in a tube. This substantiates the great potential of nanofluids as a high-energy carrier.

4. Volume Averaging theory

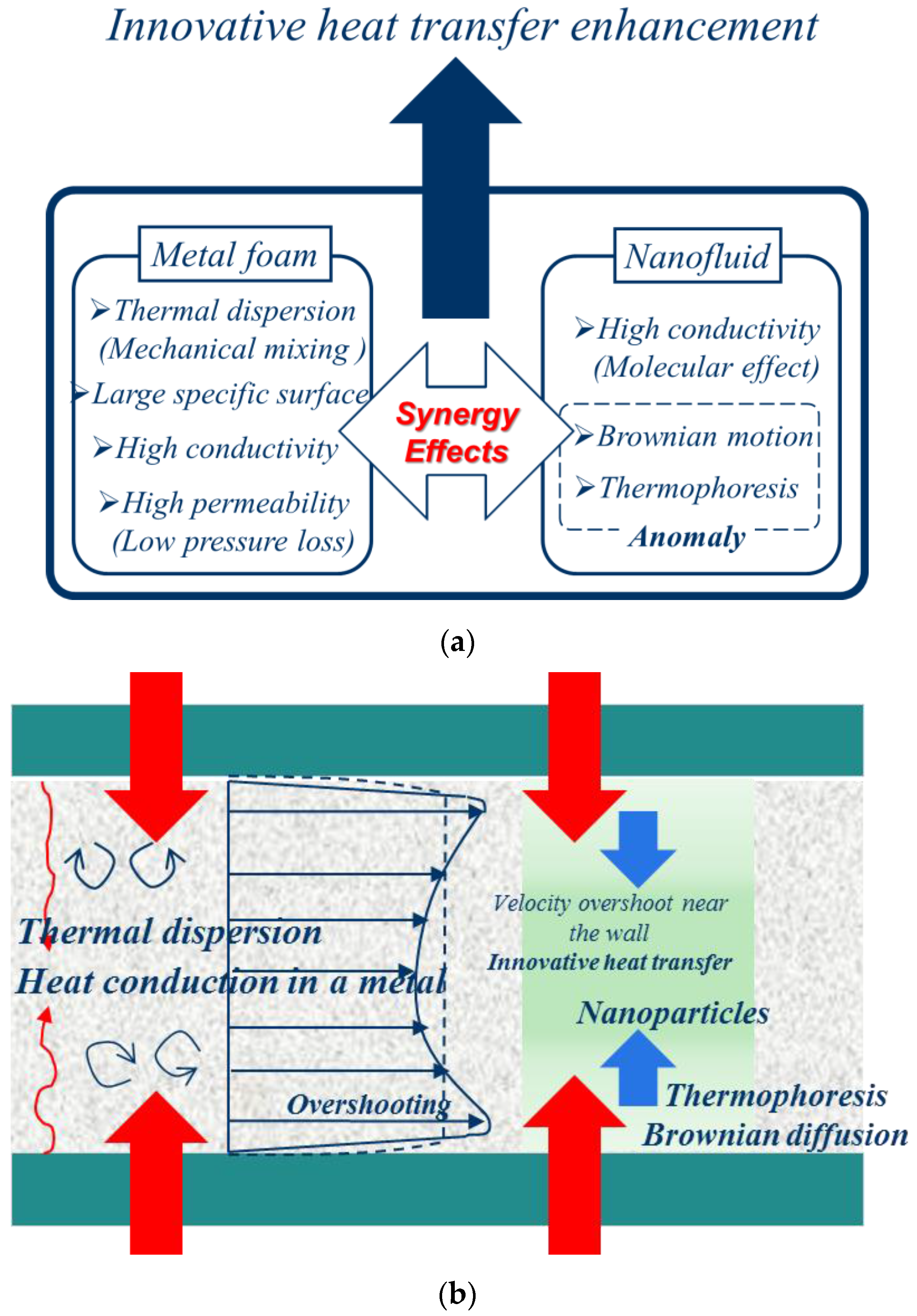

Having confirmed high heat transfer enhancement associated with nanofluids, we shall combine such nanofluids with metal foam, so as to form a passage filled with a nanofluid saturated metal foam. As illustrated in

Figure 6a, we expect heat transfer enhancement associated with nanofluids, namely, the anomalous heat transfer resulting from both Brownian diffusion and thermophoretic diffusion, while high effective thermal conductivity and thermal dispersion (

i.e., mechanical mixing) can also be expected from an embedded metal foam. These features, when combined together, may bring us the synergy effects on convective heat transfer.

Figure 6b clearly indicates that the anomalous heat transfer enhancement in nanofluids, when taking place in a passage filled with a nanofluid saturated metal foam, further leads us to an innovative heat transfer enhancement. The velocity overshooting is expected in the near wall layer, which is partially responsible for the innovative heat transfer enhancement. This interesting feature will be numerically predicted later.

In order to investigate such an innovative heat transfer enhancement, we shall introduce a volume averaging procedure and seek a complete set of the macroscopic governing equations for convection within a nanofluid saturated metal foam.

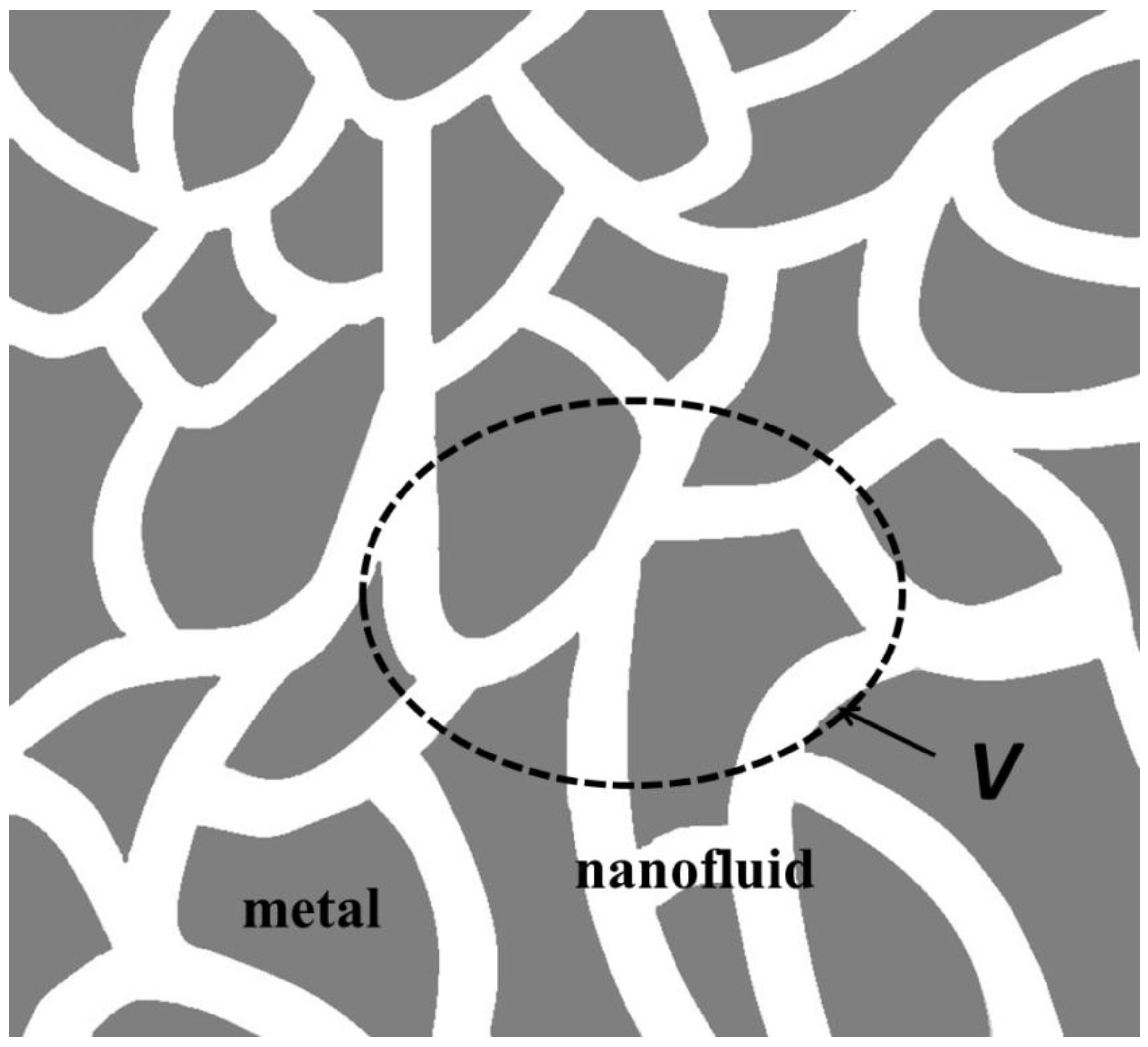

Consider a local averaging volume

in nanofluid saturated metal foam, as shown in

Figure 7. Its length scale

is much smaller than the macroscopic characteristic length, but, at the same time, much greater than the microscopic characteristic length (see, e.g., [

18,

19,

20,

21]). This condition allows us to define the volume average of a certain variable

as

Another average, namely, the intrinsic average, is given by

where

is a volume space which nanofluid occupies. Obviously, two averages are related as

, where

is the porosity, namely, local volume fraction of the nanofluid phase. Let us decompose a variable into its intrinsic average and spatial deviation from it:

All dependent variables in the microscopic governing equations for the nanofluid and metal phases are decomposed in this manner. The following spatial average relationships are used:

and

Aint represents the interfaces between fluid and solid matrix within a local averaging volume. Note

Ni is the unit vector pointing outward from nanofluid side to solid side. All dependent variables for nanofluid and metal phases are decomposed according to Equation (12). Upon exploiting the foregoing spatial average relationships, the microscopic Equations (1) to (4) are integrated over a local averaging volume. The set of macroscopic governing equations thus obtained for nanofluid and metal phases in a nanofluid saturated metal foam with uniform porosity

ε may be given as follows:

Equation (19) is obtained integrating the conduction equation in a metal phase. In the foregoing equations, many interfacial terms vanish due to no-slip and no-particle flux conditions on the nanofluid–metal interface, namely,

As these surface integral terms vanish, the equations reduce to

In the foregoing equations, the correlations associated with deviations, , and , correspond with mechanical dispersion terms, whereas the surface integral terms, , and , correspond with the tortuosity terms.

5. Mathematical Modeling

As usual, Forchheimer-extended Darcy law is introduced to describe the internal flow resistance:

while tortuosity in nanoparticle volume fraction transport is neglected since

Tortuosity terms in two energy equations may be modeled introducing the Yang–Nakayama effective porosity

([

12,

14]) as

where the effective porosity may easily be evaluated from

where

is the stagnant thermal conductivity of saturated porous medium, which can readily be measured using a standard method. However, for the cases of high conductivity porous media such as metal foams, satisfying the condition,

, there is no need to measure the stagnant thermal conductivity of saturated porous medium, since the effective porosity may well be approximated by

according to Yang and Nakayama (2010). For example, in the case of aluminum foam and water combination, we typically have

and

. Thus,

is satisfied such that

. Furthermore, Newton’s cooling law may be adopted for the interstitial heat transfer between nanofluid phase and metal foam as

where

hv is the volumetric interstitial heat transfer coefficient. Upon implementing the foregoing mathematical models, the equations reduce to

Note that Equation (29a) is exploited to express the particle tortuosity term as

In the foregoing equations, Darcian velocity vector is used in place of the intrinsic velocity vector .

6. Thermal Dispersion

Our next task in mathematical modelling is to mathematically model mechanical dispersion terms, namely, and , in terms of determinable variables. Measurement of mechanical dispersion, however, is quite formidable. Only a limited number of correlations for metal foams are available only for the case of transverse thermal dispersion. Empirical information is not available for longitudinal thermal dispersion in metal foams. As for the nanoparticle mechanical dispersion, neither theoretical nor empirical information exits so far.

Yang and Nakayama [

14] claimed that volumetric interstitial heat transfer coefficient is comparatively easy to measure, using a standard method such as the single blow method [

30]. Thus, they conducted an analytical consideration in a pore scale, and derived a theoretical relation to estimate thermal dispersion from the volumetric interstitial heat transfer coefficient, as illustrated below.

Along the macroscopic flow direction

x, the nanofluid phase energy Equation (35) at steady state may be written as

where we have dropped diffusion term, since convection term on the left hand side predominates over axial diffusion term. A magnitude analysis [

14] tells us that the diffusive term in Equation (35) is small and may well be neglected for the first approximation. This is usually true when an external scale of the flow system is much larger than a pore scale.

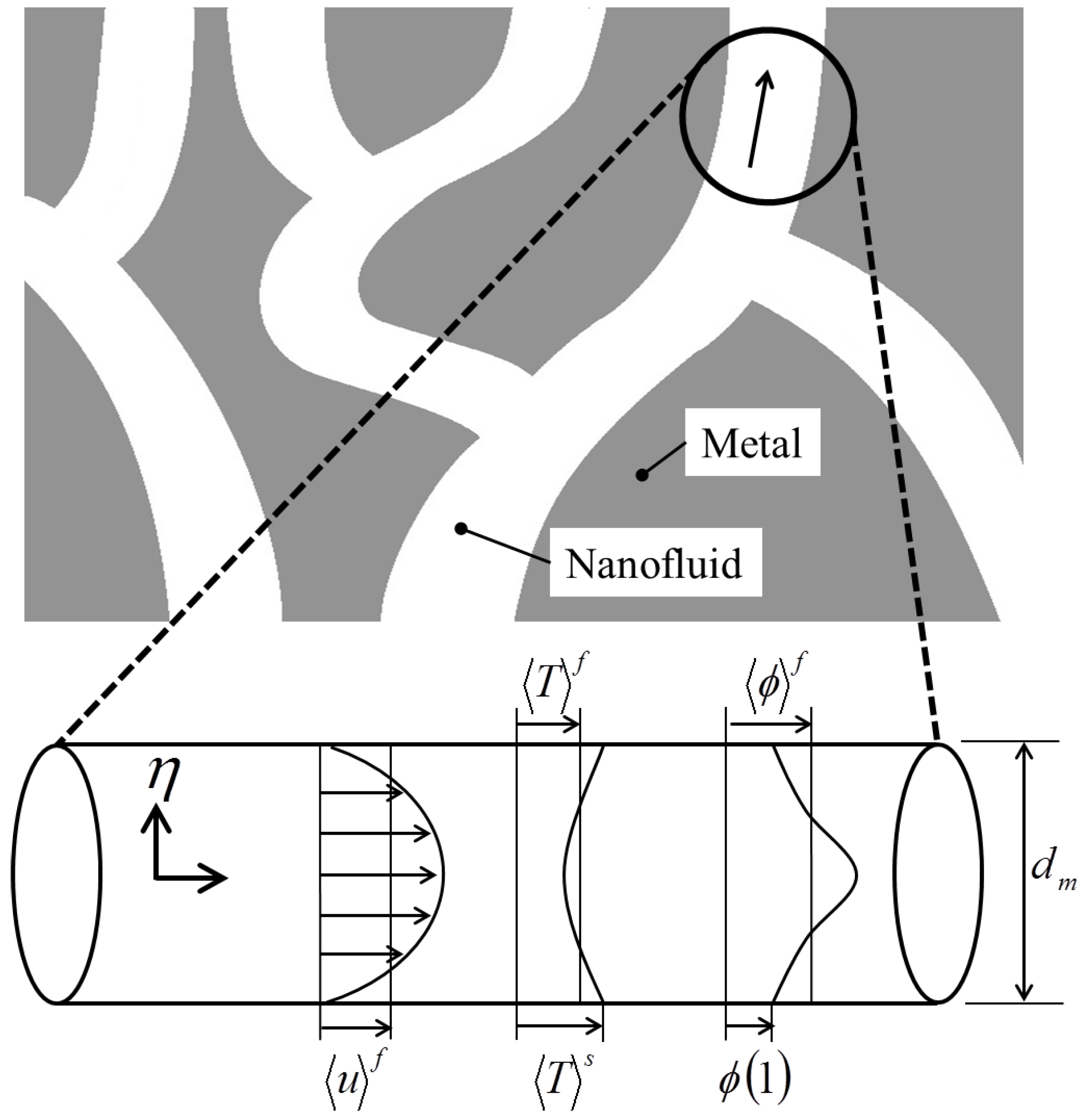

Let us consider a pore scale passage as illustrated in

Figure 8. Longitudinal thermal dispersion term may be evaluated using microscopic velocity and temperature profiles prevailing in this pore scale passage as follows:

where the volume averaged temperature difference between two phases has been replaced by the volume averaged temperature gradient, exploiting the preceding macroscopic Equation (39). Hence,

where

which is consistent with what is known as gradient diffusion hypothesis [

31]. For the volumetric interstitial heat transfer coefficient

in Equation (42), the following empirical correlation proposed by Calmidi and Mahajan [

3] may be used:

where

is the pore diameter. The correlation is based on the one developed by Zhukauskas [

32] for cylinders in laminar cross flow. Note that the functions

and

describe the velocity and temperature profiles, respectively, in a pore passage of diameter

as illustrated in

Figure 8.

and

where the dimensionless radial coordinate

normal to the pore wall is defined as

Any reasonable functions may be used for

and

in Equation (42) to estimate

such as laminar fully developed velocity and temperature profiles in a tube with its diameter

:

and

Note that

and

. Substituting the foregoing profiles into Equation (42) along with Equation. (43), we readily obtain Longitudinal (laminar):

A similar relationship can be derived for the transverse thermal dispersion. Let us consider the energy Equation (35) close enough to a heated wall surface for convection to be negligible, but at the same time, sufficiently away from the wall surface, so that the transverse thermal dispersion dominates over the stagnant thermal diffusion:

which may be integrated to yield

such that

Hence,

where

such that

. Equation (51) obtained for the transverse thermal dispersion conductivity is the same as Equation (42) obtained for the longitudinal thermal dispersion conductivity, except the difference in the multiplicative constants, namely,

and

. It is understood that

<<1. In fact, the experimental data on packed bed reported by Fried and Combarnous [

33] suggest that

is much smaller than

. In this study, we assume

, such that Transverse (laminar):

In order to estimate the longitudinal thermal dispersion for the case of fully turbulent flow, a similar procedure is used along with the wall laws as

and

where

and

are friction velocity and wall heat flux, respectively, and

is a dimensionless distance measured from the wall surface (

). Moreover,

is the von-Karman constant while both

B and

A are empirical constants. It is easy to find

and

where

Hence,

where we used Equation (39) to eliminate the wall heat flux

with specific surface

in favor of the temperature gradient. Setting

and

to 0.41 and 0.9, respectively, according to Launder and Spalding [

34], we obtain for the turbulent regime.

Longitudinal (turbulent regime):

Law of the wall was introduced by Taylor [

35] to explain high Peclet number dependence observed in dispersion of matter in a pipe flow. The same linear relationship between the thermal dispersion conductivity and Peclet number (as observed experimentally) may easily be deducted using an interstitial heat transfer coefficient correlation, which increases linearly with Peclet number. This linear relationship between the thermal dispersion coefficient and Peclet number was explained theoretically by Nakayama

et al. [

36] for high Peclet number flow through a consolidated porous medium.

As for the transverse dispersion, we again assume

, such that Transverse (turbulent regime):

As for experimental data on metal foams, only those of transverse thermal dispersion are available. The data for transverse dispersion coefficient have been correlated by Calmidi and Mahajan [

3] as follows:

Transverse (Calmidi–Mahajan):

Thus, in

Figure 9, Equation (53) for the laminar case and Equation (59) for the turbulent case are plotted together to form a solid curve for the case of

= 0.95. In the figure, the foregoing empirical correlation Equation (60) is also plotted to examine the validity of the present expressions for the transverse dispersion coefficient. The figure shows fairly good agreement between the solid line based on the present analysis and the dashed empirical line reported by Calmidi and Mahajan. It is noted that Calmidi and Mahajan’s correlation is valid only when the Peclet number

is sufficiently large. Taylor [

37] analytically proved that the dispersion coefficient is in proportion to

, that is consistent with our Equation (47) for the case of small Peclet number, in which the interstitial heat transfer coefficient stays constant. It is also interesting to note that Gelhar and Axness [

38] and Wang and Kitanidis [

39] investigated macrodispersion in heterogeneous porous media such as aquifers and geologic formations. They reported Peclet number dependence similar to what is observed in

Figure 9. Moreover, Ohsawa [

40] in his MS thesis carried out direct numerical simulations for nanofluid forced convection using a numerically generated periodic open-cell. The thermal dispersion numerically predicted by him closely follows the empirical correlation Equation (60) up to Peclet number up to 10,000, or even more. Therefore, the empirical correlation Equation (60) may well be valid in the range as indicated in

Figure 9.

7. Nanoparticle Mechanical Dispersion

For the first time, we shall introduce a mathematical model for the nanoparticle mechanical dispersion. The nanoparticle conservation Equation (37) at steady state is written along the macroscopic flow direction

x, as

As illustrated in

Figure 8, we consider nanoparticle conservation along a pore scale conduit with its diameter

. Thus, nanoparticle mechanical dispersion flux

can be expressed as

where

Function

for the nanoparticle profile may be estimated by solving Equation (4) in a pore conduit:

which can easily be solved with Equations (6a) and (6b) being substituted:

since

. Thus,

Using Equation (46a,b) for velocity and temperature profiles, respectively, we readily obtain

Thus

where

is a dimensionless function of local volume averaged temperatures, describing the ratio of Brownian and thermophoretic diffusions within a pore conduit, as introduced by Yang

et al. [

23]. Note that absolute value of

in most cases is very large, and that, under local thermal equilibrium condition, namely,

, grows infinitely. Equation (68) may be substituted into Equation (61) to yield

Hence, nanoparticle mechanical dispersion works either to suppress or to enhance effective diffusion, as can be seen from the denominator . It suppresses effective diffusion where the local temperature of metal foam phase is higher than that of nanofluid phase (i.e., > 0). On the other hand, it enhances the diffusion where the local temperature of metal foam phase is lower than that of nanofluid phase (i.e., < 0). However, this effect of nanoparticle mechanical dispersion on the effective diffusion is limited only to a moderate range of , where local thermal non-equilibrium is discernible. In the region where is very large under nearly local thermal equilibrium, the nanoparticle mechanical dispersion flux , vanishes, and only stagnant particle diffusion remains. In this way, nanoparticle mechanical dispersion flux varies across the channel, depending on the degree of local thermal non-equilibrium there.

We shall again consider the nanoparticle conservation Equation (37) close enough to the wall surface for convection to be negligible:

The nanoparticle mechanical dispersion flux

near the wall surface may be estimated as follows:

Thus, the transverse nanoparticle mechanical dispersion is so small that it can totally be neglected, irrespective of the degree of local thermal non-equilibrium. Due to no-flux condition at the wall, Equation (71) naturally reduces to

Unfortunately, no experimental data are available for either transverse or longitudinal coefficients of nanoparticle mechanical dispersion.

8. Mathematical Model for Hydro-Dynamically and Thermally Fully Developed Flows

We shall refer to

Figure 10, and consider hydrodynamically and thermally fully developed flows in both channel and tube subject to constant heat flux, filled with a nanofluid saturated metal foam. The walls are subject to axially constant heat flux and circumferentially constant wall temperature (

i.e., constant heat flux everywhere).

The macroscopic momentum Equation (34) can be numerically solved along with the macroscopic continuity Equation (33) for the case of fully developed flow in a tube. Such a volume averaged velocity profile is presented in

Figure 11, in which the velocity is seen higher close to the wall, since the viscosity there is lower. This overshooting of the velocity works to carry heat effectively away from the heated wall.

In the following analytical treatment, however, the momentum Equation (34) is simplified using Forchheimer extended Darcy law, in which Brinkman term (

i.e., macroscopic viscous diffusion term) is dropped, allowing the Darcian velocity slip on the wall. This Forchheimer extended Darcy law is valid for most of metal foams except for the case of extremely high permeability. Thus, for this case of the channel flow, the volume average Equations (33) to (37) reduce to:

Following Equations (59), transverse thermal dispersion coefficient may be evaluated from

Moreover, the interstitial volumetric coefficient is evaluated from Equation (43). Note that the continuity equation yields and .

The origin of vertical coordinate

y is set on the lower wall. The boundary conditions are given by

Kuwahara

et al. [

12] considered two extreme cases for possible wall temperature difference between solid and fluid phases, namely, locally uniform heat flux wall and locally thermal equilibrium wall, and concluded that the locally thermal equilibrium wall is much closer to the reality. Hence, we assume:

where

is the wall temperature.

increases linearly downstream under constant heat flux. Nanoparticle conservation Equation (77) indicates that diffusion mass flux of nanoparticles is constant across the channel. Since the wall is impermeable, the boundary condition Equation (80) holds such that effective Brownian diffusion flux and effective thermophoretic diffusion flux cancel out everywhere across the channel. Energy Equations (75) and (76) may be added together and integrated over the lower half channel from

y = 0 to

H with boundary conditions Equations (79) and (80) to give

where the subscript 0 refers to the wall at

, and

denotes the average value over the cross-section such that

is the bulk mean temperature. Likewise, quantities with subscript

B denote bulk quantities such as

The foregoing considerations on both nanoparticle diffusion flux and axial temperature gradient will be implemented to obtain analytical expressions in a dimensionless form. The momentum Equation (74) may be arranged in a dimensionless form as

Thus, for the case of Forchheimer extended Darcy flow (

i.e.,

), the velocity profile is described algebraically as the viscosity of nanofluid is provided as function of the nanoparticle volume fraction. The other governing equations are given in differential forms as follows:

Dimensionless coordinate, velocity and temperature are defined as

Furthermore, Darcy, Lewis, Peclet, and Hagen numbers are defined as follows:

where the properties with subscript 0 should be evaluated at the wall according to Equations (5a) to (6b), (30) and (31). For example, the stagnation thermal conductivity at wall where

may be evaluated according to Equations (5d), (30) and (31) as

The dimensionless parameter

is related to the ratio of macroscopic Brownian and thermophoretic diffusivities.

can range over a wide range from 0.1 to 10 for typical cases of alumina and copper nanoparticles with

~10 nm and the bulk mean particle volume fraction

~0.01. The ratio of wall and fluid temperature difference to absolute temperature, namely,

, is usually much smaller than unity, as estimated by Buongiorno [

17]. Similarity between “microscopic” ratio

(Equation (69)) and “macroscopic” ratio

(Equation (92a)) is worth noting, since the former describes the local ratio of microscopic Brownian and thermophoretic diffusivities in a pore scale, whereas the latter describes the ratio of macroscopic Brownian and thermophoretic diffusivities in a channel filled with a nanofluid saturated metal foam.

In reality, the bulk mean particle volume fraction is given, while that at the wall is unknown. However, for the sake of computational convenience, is prescribed and is calculated later to find out as a function of .

The energy Equations (87) and (88) can be combined to form a third order Ordinary Differential Equation (O.D.E.) with respect to

as

where

and Equation (89) can easily be integrated with

to obtain

The foregoing third order O.D.E. Equation (95) may easily be solved by using a standard integration scheme such as Runge–Kutta–Gill method (e.g., [

21]). Appropriate boundary conditions for the equation are given by

which are based on the original boundary conditions given by Equations (81b) and (82).

A similar procedure based on the cylindrical coordinate system as shown in

Figure 10b readily yields the following set of transformed equations for the case of circular tube:

where

The boundary conditions in the cylindrical coordinate are the same as those given by Equation (98a,b). Moreover, Equation (97) for the volume averaged nanoparticle volume fraction holds also for the case of cylindrical coordinate system. However, note that the average value

for the case of the tube is computed by

where

. The corresponding dimensionless quantities

to

are defined just as presented in Equations (91a) to (93d) replacing the channel half height

H by the tube radius

R.

9. Results and Discussion

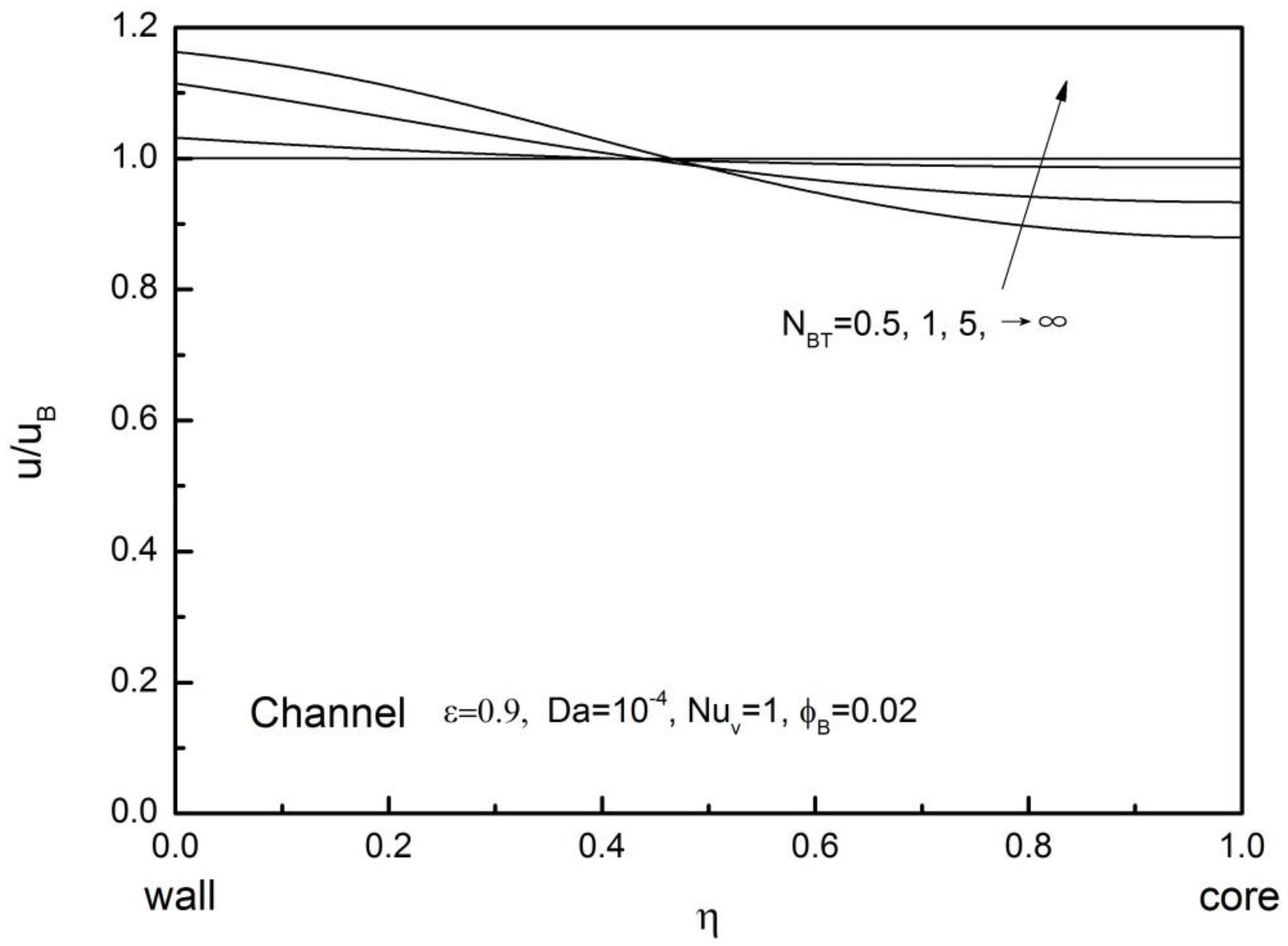

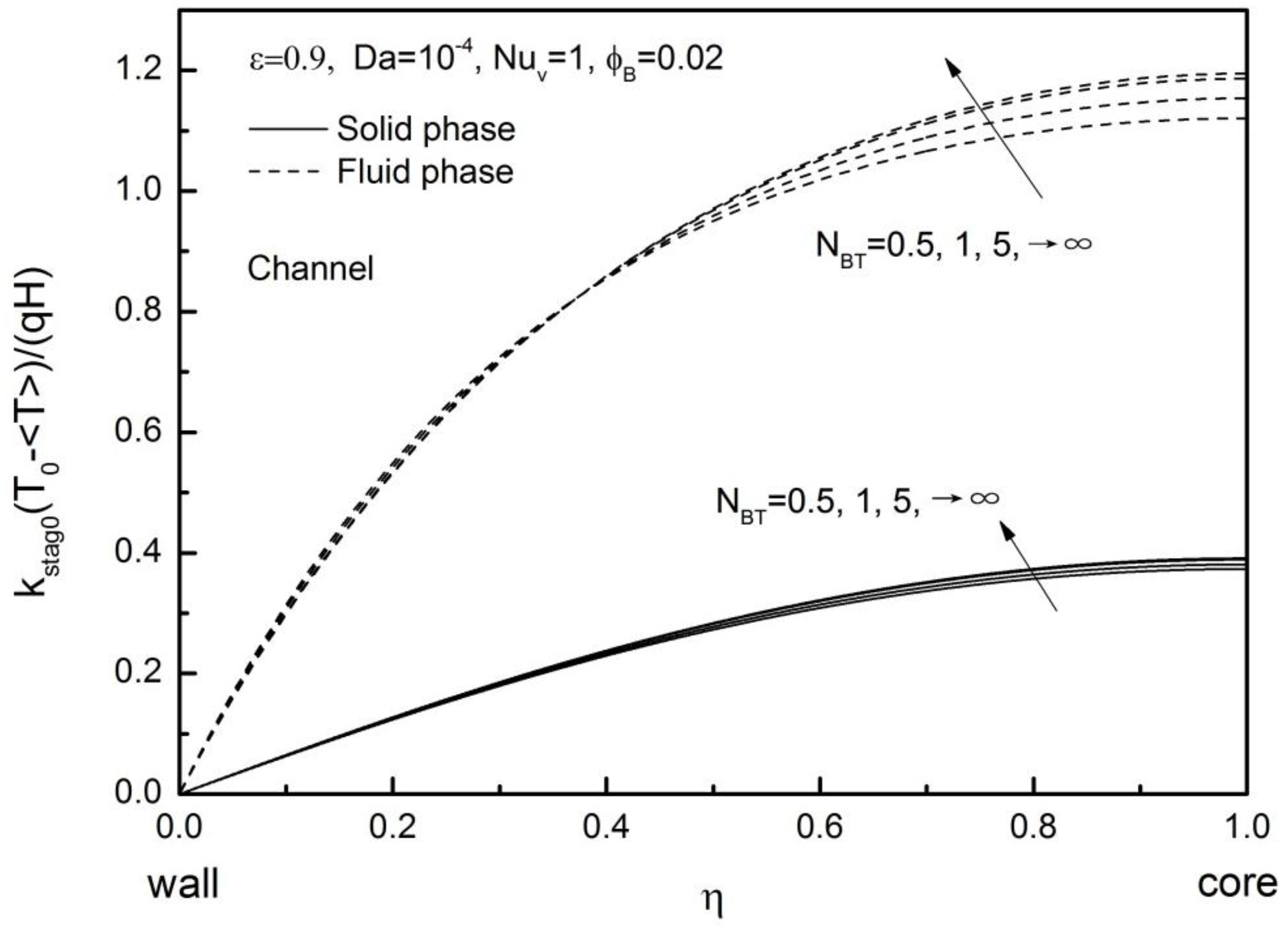

The foregoing set of equations may be integrated numerically using the Runge–Kutta–Gill method for the case of channel with

= 0.9,

= 10

−4,

= 0.5 and

= 0.02.

Figure 12 shows the effects of the interstitial Nusselt number

on fluid and solid temperature profiles.

The temperature profile of nanofluid and that of metal foam tend to get closer each other for sufficiently large , in which local thermal equilibrium holds. Usually, the solid temperature is higher than the nanofluid temperature (i.e., is smaller and flatter than ).

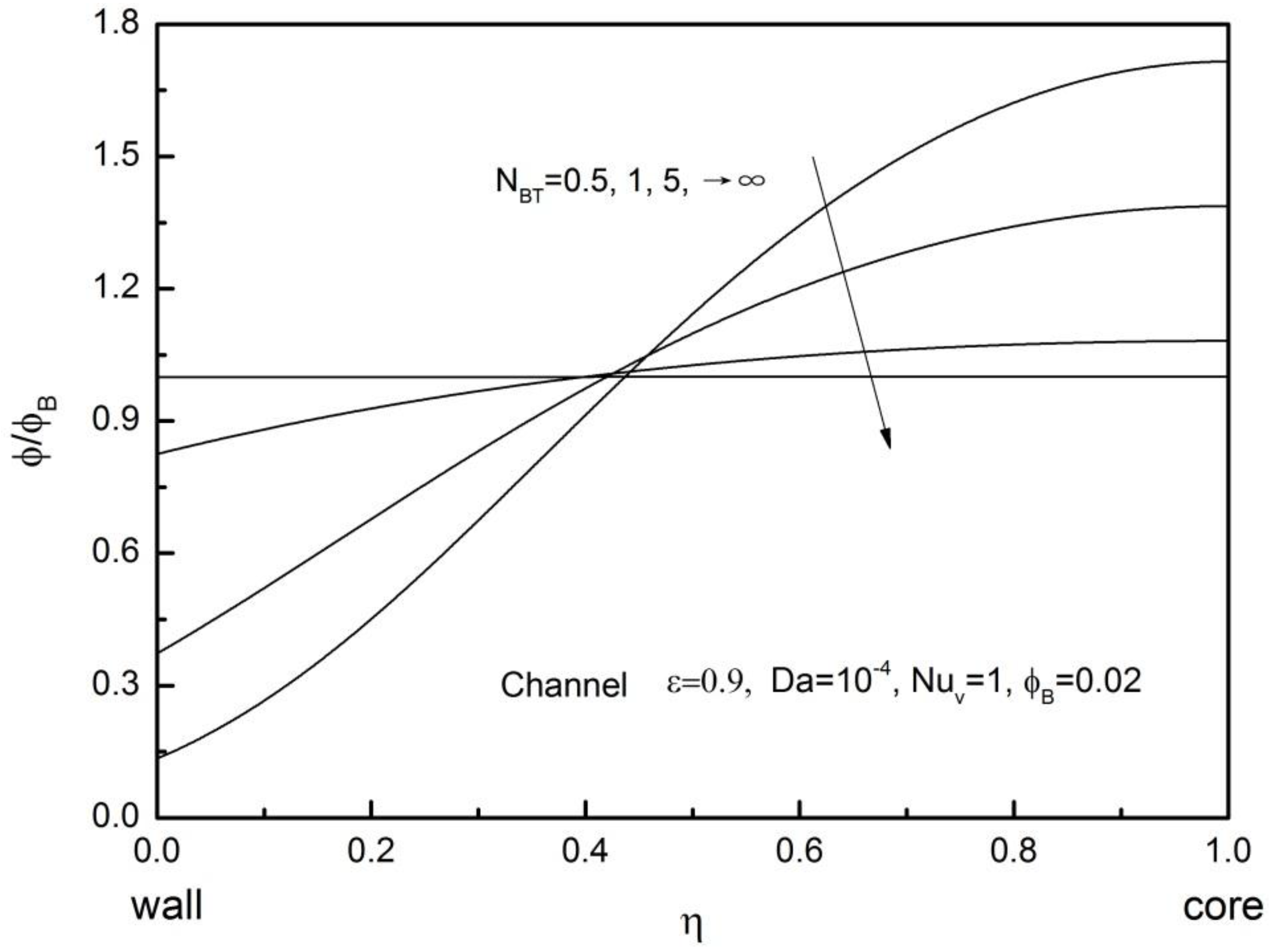

The corresponding particle volume fraction and velocity profiles in the channel are shown in

Figure 13 and

Figure 14, respectively. The nanoparticle volume fraction distribution becomes somewhat flatter as increasing

, since the nanofluid temperature tends to follow the solid temperature, as witnessed in

Figure 13. As can be seen from

Figure 13, the nanoparticle volume fraction gradually converges to a profile corresponding to the case of

.

Figure 14 clearly shows that the velocity is higher near the heated wall where viscosity is less, as thermophoretic diffusion dominates over Brownian diffusion, driving nanoparticles away from the wall.

By changing the value , another series of computations were conducted with = 0.9, = 10−4. = 1 and = 0.02, so as to investigate the effect of the ratio of macroscopic Brownian and thermophoretic diffusivities, , on nanoparticle volume fraction profile, velocity profile and both fluid and solid temperature profiles.

As shown in

Figure 15, the nanoparticle volume fraction becomes uniform for large

. Because Brownian diffusion dominates over thermophoretic diffusion, nanoparticles are dispersed evenly for large

.

Figure 16 shows that the velocity profile becomes completely flat under such a uniform nanoparticle volume fraction distribution, resulting in a plug flow.

In

Figure 17, both nanofluid temperature and metal foam temperature are plotted for a range of

.

is only at a moderate level such that a substantial difference can be observed between two temperatures. As can be confirmed from the figure, however, the effects of

on the temperature profiles are rather limited.

9.1. Asymptotic Solutions for the Case of Nearly Uniform Nanoparticle Distribution ()

Brownian diffusion overwhelms thermophoretic diffusion for the case of sufficiently small nanoparticle diameter, such that its macroscopic ratio

becomes much greater than unity. Equation (97) under such cases yields

where

. The foregoing equation indicates that the profile of volume averaged nanoparticle volume fraction

becomes similar to that of nanofluid phase temperature

. Moreover, it tends to be uniform for sufficiently large

, as consistently observed in

Figure 15. Under such uniform distribution of volume averaged nanoparticle volume fraction, all thermophysical properties become uniform across the channel.

9.1.1. Channel Flows

Thus, the third order O.D.E. Equation (91) and nanofluid temperature Equation (96) with the boundary conditions Equations (98a) and (98b) yields the following analytic solutions:

and

where

and

Nusselt number of our interest is given by

The ratio of heat transfer coefficient for convection in a nanofluid saturated metal foam to that for the case of base fluid convection without a metal foam is given by

9.1.2. Tube Flows

The corresponding set of solutions for the case of tubes may be obtained by solving Equation (99) as

where

is the modified zero order Bessel function of the first kind. The dimensionless nanofluid temperature is obtained substituting Equations (108) into (100) as

where the dimensionless bulk velocity is given by Equation (105b). The corresponding Nusselt number may be numerically evaluated as

The ratio of heat transfer coefficient for convection in a nanofluid saturated metal foam to that for the case of base fluid convection without a metal foam is given by

9.2. Asymptotic Solutions for the Case of Nearly Local Thermal Equilibrium ()

Equation (96) for the channel flow case and Equation (100) for the tube flow case clearly indicate when the interstitial volumetric coefficient is sufficiently high (i.e., ). Thus, local thermal equilibrium holds everywhere over the cross-section.

9.2.1. Channel Flows

Equation (87) readily yields analytic solutions.

This integral equation can be approximated very well by

Substitution of the foregoing temperature profile into Equation (97) readily gives the profile of volume averaged nanoparticle volume fraction. The corresponding Nusselt number is given by

The ratio of heat transfer coefficient for convection in a nanofluid saturated metal foam to that for the case of base fluid convection without a metal foam is given by

9.2.2. Tube Flows

The corresponding set of the solutions for the case of tubes may be obtained from Equation (99) as

which may well be approximated by

Thus, the profile of volume averaged temperature given by Equation (117) and that of nanoparticle volume fraction given by its substitution into Equation (97) for the tube are similar to those for the channel. Accordingly, Nusselt number for the tube is given by

The ratio of heat transfer coefficient for convection in a nanofluid saturated metal foam to that for the case of base fluid convection without a metal foam is given by

Heat transfer enhancement in a nanoparticle saturated metal foam can be partly due to an increase in its stagnant thermal conductivity, which results from both highly conductive nanoparticles and consolidated meal foam, and partly due to intensified nanofluid mixing resulting from mechanical dispersion within a foam. This enhancement can best be illustrated in the foregoing Equation (119). The first term in the right hand side gives the heat transfer rate increase due to embedding of metal foam and addition of nanoparticles, while the second term describes heat transfer enhancement due to thermal dispersion.

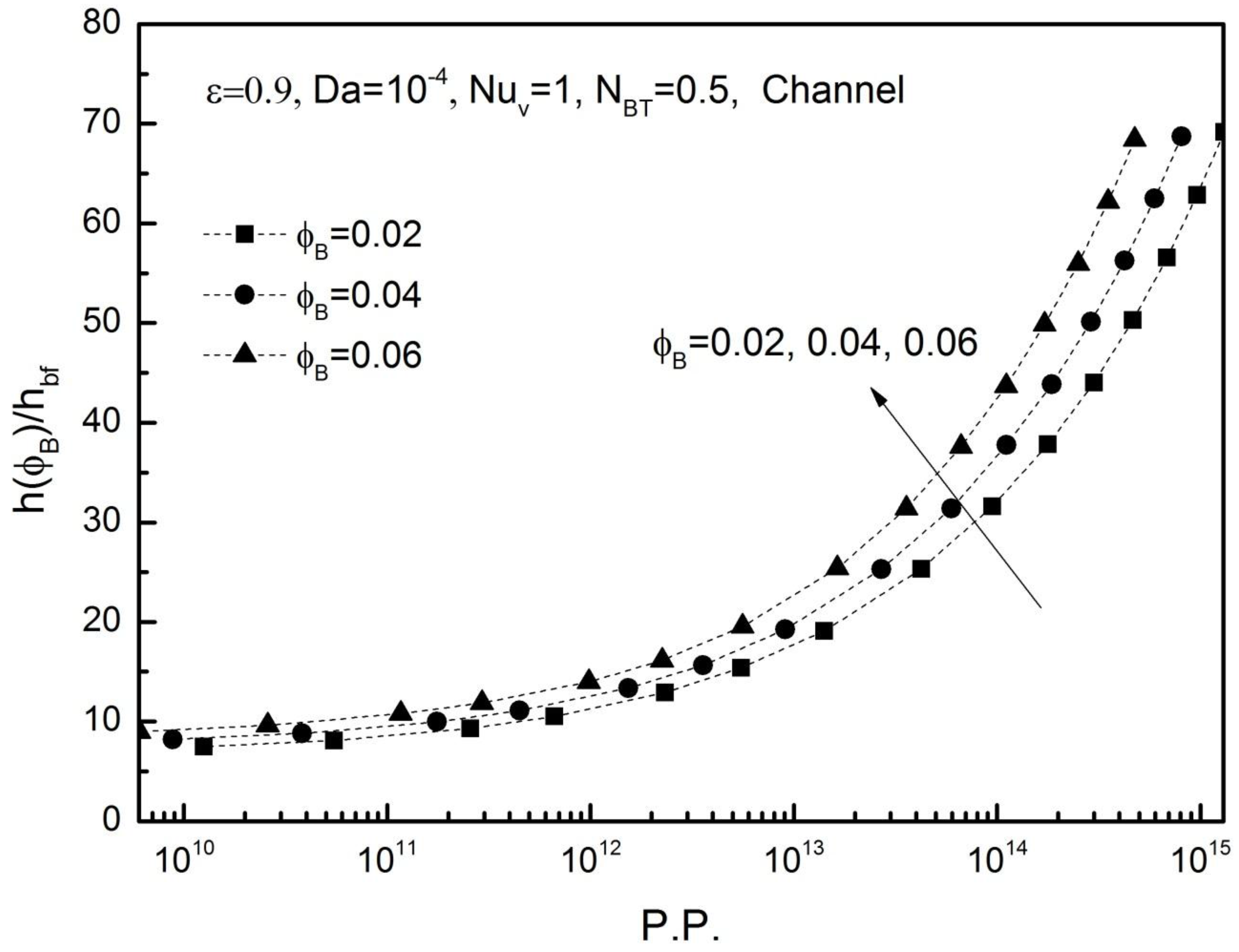

9.3. Heat Transfer Performance Evaluation

Figure 18 shows heat transfer coefficient ratios

for given

against a dimensionless pumping power:

is plotted in a possible range of P.P. = 6.0 × 109 − 1.3 × 1015 (corresponding to = 0.01 to 1 m/s, 2R = 0.02 m, = 0.001 m) for the tube. The figure clearly indicates that heat transfer coefficient for the tube filled with a nanofluid saturated metal foam is much higher than that for a tube filled with a base fluid. The ratio increases towards 80 as increasing the pumping power , in which thermal dispersion becomes significant. Naturally, higher volume fraction of nanofluid results in higher heat transfer coefficient, especially when is large such that thermal dispersion is quite significant.

Figure 19 shows the effects of

on the heat transfer ratio

. As expected from

Figure 17 showing the temperature profiles, which are fairly insensitive to

, the heat transfer ratios obtained with different values of

almost coincide one another.

Figure 20, on the other hand, shows effects of

on the heat transfer coefficient ratio

, which clearly indicates that higher interstitial heat transfer coefficient yields higher macroscopic heat transfer coefficient. Therefore, combination of metal foams and nanofluids is believed to bring unconventionally high heat transfer coefficients.

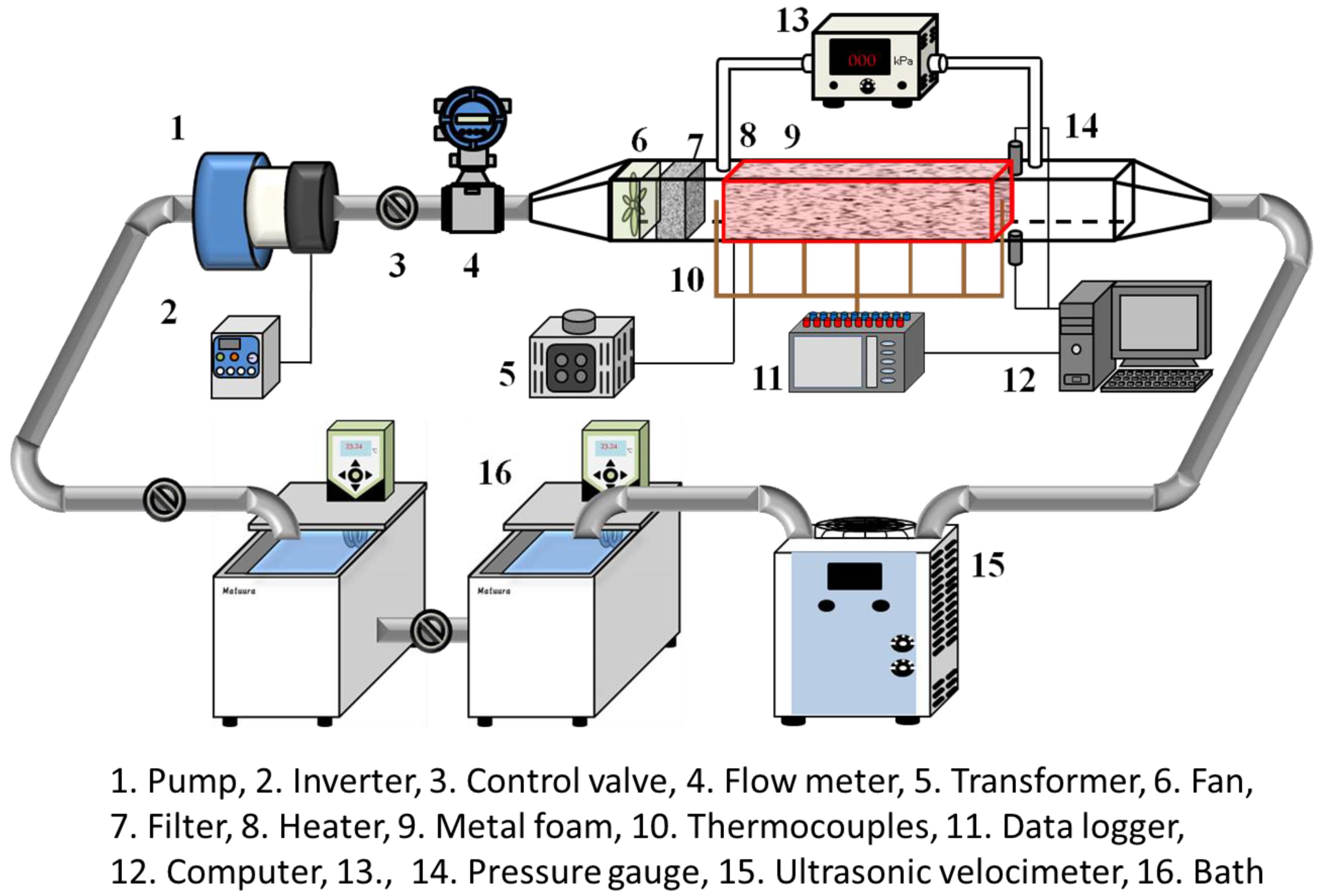

The experimental verification is underway using the experimental set-up, as shown in

Figure 21. The experimental results obtained from the program partially supported by the JSPS Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research B, will be available near future.