Cardiovascular Nursing in Rehabilitative Cardiology: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

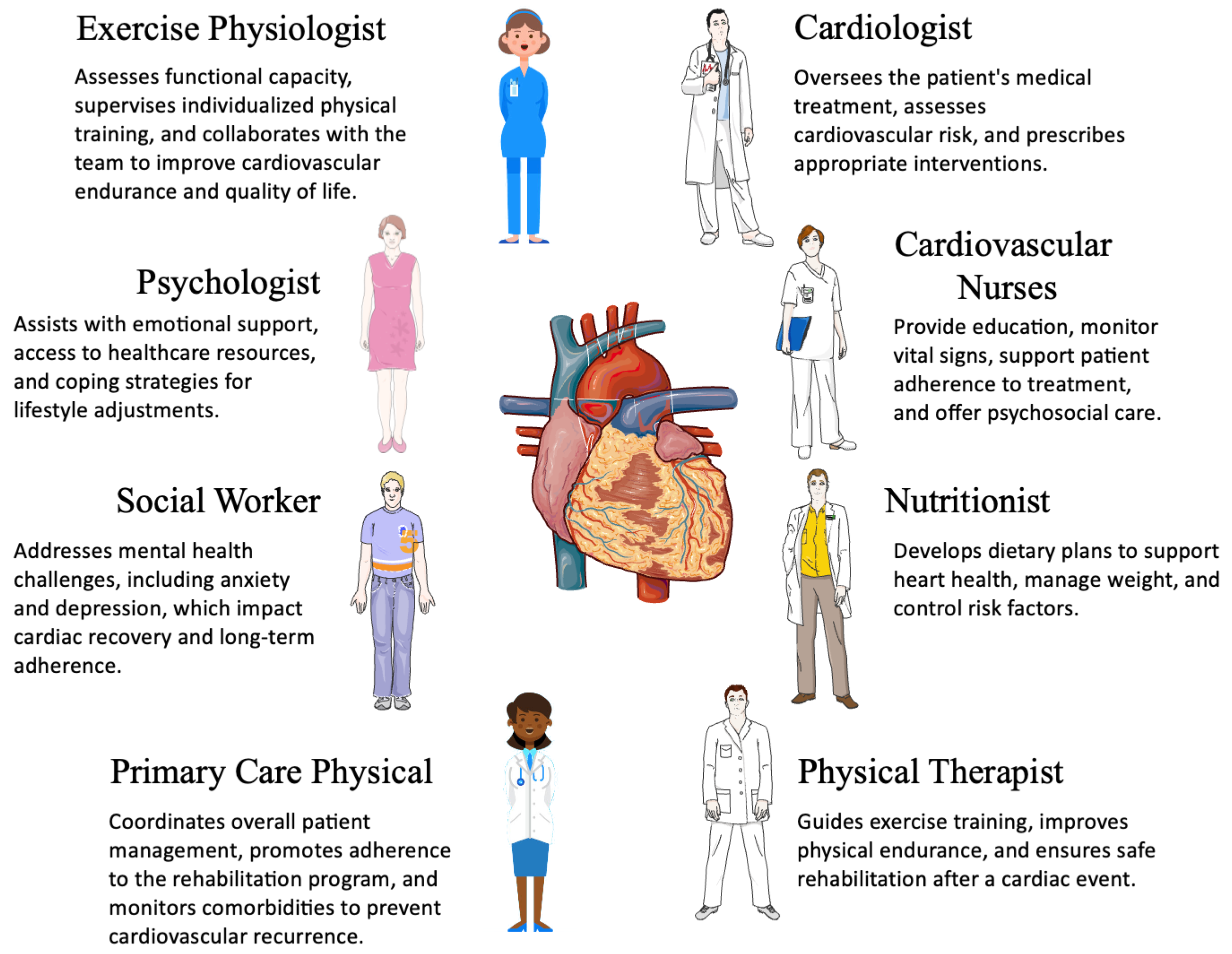

2. Rehabilitative Cardiology, Goals, Phases, and Interdisciplinary Approach

- Patients with acute coronary syndrome—including ST elevation myocardial infarction, non-ST elevation myocardial infarction, and unstable angina—and all patients undergoing reperfusion;

- Patients with newly diagnosed chronic heart failure and chronic heart failure with a step change in clinical presentation;

- Patients with a heart transplant and ventricular assist device;

- Patients who have undergone surgery for implantation of an intra-cardiac defibrillator or cardiac resynchronization therapy for reasons other than acute coronary syndrome and heart failure;

- Patients with heart valve replacements for reasons other than acute coronary syndrome and heart failure;

- Patients with a confirmed diagnosis of exertional angina.

- Phase I (acute): This phase, known as the hospital phase, begins as an inpatient setting shortly after a cardiovascular event or intervention. It typically starts with assessing the patient’s physical ability and motivation for rehabilitation. Therapists and nurses may start by guiding patients through non-fatiguing exercises in the bed or at the bedside, focusing on a range of motion and limiting hospital deconditioning. The rehabilitation team can also focus on activities of daily living (ADLs) and educate the patient to avoid over-stress. Patients are encouraged to remain relatively rested until complete stabilization.

- Phase II (subacute): This early outpatient phase begins once the patient is medically stable and discharged from the hospital. The focus shifts toward supervised exercise, lifestyle modification, and comprehensive patient education. Patients undergo individualized assessments to determine their functional capacity, and interventions are tailored accordingly. This phase typically lasts 3 to 6 weeks.

- Phase III (maintenance): This phase emphasizes sustained lifestyle changes, continued physical activity, and self-management strategies. The goal is to reinforce healthy behaviors, optimize medication adherence, and monitor long-term risk factors. Patients are encouraged to participate in structured exercise programs and maintain regular follow-ups with healthcare providers.

- Phase IV (long-term prevention): This ongoing phase supports high-risk patients in preventing disease progression. It involves continued education, remote monitoring, and the integration of digital health tools, such as telemedicine, to enhance patient engagement and adherence.

- Cardiologists are usually program coordinators (in Israel, Ireland, Russia, Portugal, Spain, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Belgium, and France).

- Rehabilitation specialists can take the lead (in Estonia, Portugal, and Bosnia and Herzegovina).

- Nurses and/or physiotherapists are in charge (in Sweden, Malta, Greece, and the United Kingdom). In Israel, Egypt, Portugal, the United Kingdom, and Greece an exercise physiologist/master’s may be included in the phase II team together with the physiotherapists. On the contrary, phase II exercise classes in Ireland, Poland, Lebanon, Spain, Malta, Italy, and Belgium are only run by physiotherapists [23].

3. Roles, Responsibilities and Clinical Impact of Cardiovascular Nurses in Rehabilitation Settings

3.1. Nursing Care in the Different Phases of Cardiac Rehabilitation

3.2. Patient Education and Health Literacy and Multidisciplinary Team Integration

4. Evidence-Based Practices in Cardiovascular Nursing

5. Challenges and Opportunities

5.1. Challenges for Cardiovascular Nurses in Rehabilitation Settings

5.2. Opportunities for Improving Cardiovascular Nursing in Rehabilitation Settings

6. Conclusions and Future Prospective

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Cardiovascular Disease. 2017. Available online: http://www.who.int/cardiovascular_diseases/en/ (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Anderson, L.; Oldridge, N.; Thompson, D.R.; Zwisler, A.D.; Rees, K.; Martin, N.; Taylor, R.S. Exercise-Based Cardiac Rehabilitation for Coronary Heart Disease: Cochrane Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 67, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piepoli, M.F.; Hoes, A.W.; Agewall, S.; Albus, C.; Brotons, C.; Catapano, A.L.; Cooney, M.T.; Corra, U.; Cosyns, B.; Deaton, C.; et al. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts) Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 2315–2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heran, B.S.; Chen, J.M.; Ebrahim, S.; Moxham, T.; Oldridge, N.; Rees, K.; Thompson, D.R.; Taylor, R.S. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011, CD001800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.C., Jr.; Benjamin, E.J.; Bonow, R.O.; Braun, L.T.; Creager, M.A.; Franklin, B.A.; Gibbons, R.J.; Grundy, S.M.; Hiratzka, L.F.; Jones, D.W.; et al. AHA/ACCF Secondary Prevention and Risk Reduction Therapy for Patients with Coronary and other Atherosclerotic Vascular Disease: 2011 update: A guideline from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation 2011, 124, 2458–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.M.; King-Shier, K.M.; Duncan, A.; Spaling, M.; Stone, J.A.; Jaglal, S.; Angus, J. Factors influencing referral to cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention programs: A systematic review. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2013, 20, 692–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naderi, S.H.; Bestwick, J.P.; Wald, D.S. Adherence to drugs that prevent cardiovascular disease: Meta-analysis on 376,162 patients. Am. J. Med. 2012, 125, 882–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ades, P.A.; Keteyian, S.J.; Wright, J.S.; Hamm, L.F.; Lui, K.; Newlin, K.; Shepard, D.S.; Thomas, R.J. Increasing Cardiac Rehabilitation Participation From 20% to 70%: A Road Map From the Million Hearts Cardiac Rehabilitation Collaborative. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2017, 92, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunlay, S.M.; Witt, B.J.; Allison, T.G.; Hayes, S.N.; Weston, S.A.; Koepsell, E.; Roger, V.L. Barriers to participation in cardiac rehabilitation. Am. Heart J. 2009, 158, 852–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, P.M. Cardiovascular Nursing: The Future is Bright. Heart Lung Circ. 2016, 25, 757–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riegel, B.; Moser, D.K.; Buck, H.G.; Dickson, V.V.; Dunbar, S.B.; Lee, C.S.; Lennie, T.A.; Lindenfeld, J.; Mitchell, J.E.; Treat-Jacobson, D.J.; et al. Self-Care for the Prevention and Management of Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke: A Scientific Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e006997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnason, S.; Zimmerman, L.; Young, L. An integrative review of interventions promoting self-care of patients with heart failure. J. Clin. Nurs. 2012, 21, 448–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichtman, J.H.; Froelicher, E.S.; Blumenthal, J.A.; Carney, R.M.; Doering, L.V.; Frasure-Smith, N.; Freedland, K.E.; Jaffe, A.S.; Leifheit-Limson, E.C.; Sheps, D.S.; et al. Depression as a risk factor for poor prognosis among patients with acute coronary syndrome: Systematic review and recommendations: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2014, 129, 1350–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doering, L.V.; Cross, R.; Vredevoe, D.; Martinez-Maza, O.; Cowan, M.J. Infection, depression, and immunity in women after coronary artery bypass: A pilot study of cognitive behavioral therapy. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2007, 13, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dracup, K.; Moser, D.K.; Pelter, M.M.; Nesbitt, T.S.; Southard, J.; Paul, S.M.; Robinson, S.; Cooper, L.S. Randomized, controlled trial to improve self-care in patients with heart failure living in rural areas. Circulation 2014, 130, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.J.; Beatty, A.L.; Beckie, T.M.; Brewer, L.C.; Brown, T.M.; Forman, D.E.; Franklin, B.A.; Keteyian, S.J.; Kitzman, D.W.; Regensteiner, J.G.; et al. Home-Based Cardiac Rehabilitation: A Scientific Statement From the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation, the American Heart Association, and the American College of Cardiology. Circulation 2019, 140, e69–e89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.H.; Neubeck, L.; Gallagher, R. Educational Preparation, Roles, and Competencies to Guide Career Development for Cardiac Rehabilitation Nurses. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2017, 32, 244–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.J.; Yu, D.S. Effects of a nurse-led eHealth cardiac rehabilitation programme on health outcomes of patients with coronary heart disease: A randomised controlled trial. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 122, 104040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehabilitation after cardiovascular diseases, with special emphasis on developing countries. In Report of a WHO Expert Committee; World Health Organization Technical Report Series; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1993; Volume 831, pp. 1–122.

- Molloy, C.; Long, L.; Mordi, I.R.; Bridges, C.; Sagar, V.A.; Davies, E.J.; Coats, A.J.; Dalal, H.; Rees, K.; Singh, S.J.; et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for adults with heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2024, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzwedel, A.; Jensen, K.; Rauch, B.; Doherty, P.; Metzendorf, M.I.; Hackbusch, M.; Voller, H.; Schmid, J.P.; Davos, C.H. Effectiveness of comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation in coronary artery disease patients treated according to contemporary evidence based medicine: Update of the Cardiac Rehabilitation Outcome Study (CROS-II). Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2020, 27, 1756–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandercock, G.; Hurtado, V.; Cardoso, F. Changes in cardiorespiratory fitness in cardiac rehabilitation patients: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 167, 894–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candelaria, D.; Randall, S.; Ladak, L.; Gallagher, R. Health-related quality of life and exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation in contemporary acute coronary syndrome patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Qual. Life Res. 2020, 29, 579–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, G.E.; Wells, A.; Doherty, P.; Heagerty, A.; Buck, D.; Davies, L.M. Cost-effectiveness of cardiac rehabilitation: A systematic review. Heart 2018, 104, 1403–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelliccia, A.; Sharma, S.; Gati, S.; Back, M.; Borjesson, M.; Caselli, S.; Collet, J.P.; Corrado, D.; Drezner, J.A.; Halle, M.; et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines on sports cardiology and exercise in patients with cardiovascular disease. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 17–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piepoli, M.F.; Hoes, A.W.; Agewall, S.; Albus, C.; Brotons, C.; Catapano, A.L.; Cooney, M.-T.; Löllgen, H.; Marques-Vidal, P.; Perk, J. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice : The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts). Int. J. Behav. Med. 2017, 24, 321–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibanez, B.; James, S.; Agewall, S.; Antunes, M.J.; Bucciarelli-Ducci, C.; Bueno, H.; Caforio, A.L.P.; Crea, F.; Goudevenos, J.A.; Halvorsen, S.; et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 119–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collet, J.P.; Thiele, H.; Barbato, E.; Barthelemy, O.; Bauersachs, J.; Bhatt, D.L.; Dendale, P.; Dorobantu, M.; Edvardsen, T.; Folliguet, T.; et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2021, 74, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowie, A.; Buckley, J.; Doherty, P.; Furze, G.; Hayward, J.; Hinton, S.; Jones, J.; Speck, L.; Dalal, H.; Mills, J.; et al. Standards and core components for cardiovascular disease prevention and rehabilitation. Heart 2019, 105, 510–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post Myocardial Infarction: Secondary Prevention in Primary and Secondary Care for Patients Following a Myocardial Infarction; National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: London, UK, 2007.

- Piepoli, M.F.; Corra, U.; Adamopoulos, S.; Benzer, W.; Bjarnason-Wehrens, B.; Cupples, M.; Dendale, P.; Doherty, P.; Gaita, D.; Hofer, S.; et al. Secondary prevention in the clinical management of patients with cardiovascular diseases. Core components, standards and outcome measures for referral and delivery: A policy statement from the cardiac rehabilitation section of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation. Endorsed by the Committee for Practice Guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2014, 21, 664–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLara, D.L.; Pollack, L.M.; Wall, H.K.; Chang, A.; Schieb, L.; Matthews, K.; Stolp, H.; Pack, Q.R.; Casper, M.; Jackson, S.L. County-Level Cardiac Rehabilitation and Broadband Availability: Opportunities for Hybrid Care in the United States. J. Cardiopulm. Rehabil. Prev. 2024, 44, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Macedo, R.M.; Faria-Neto, J.R.; Costantini, C.O.; Casali, D.; Muller, A.P.; Costantini, C.R.; de Carvalho, K.A.; Guarita-Souza, L.C. Phase I of cardiac rehabilitation: A new challenge for evidence based physiotherapy. World J. Cardiol. 2011, 3, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.S.; Fredericks, S.; Jones, I.; Neubeck, L.; Sanders, J.; De Stoutz, N.; Thompson, D.R.; Wadhwa, D.N.; Grace, S.L. Global perspectives on heart disease rehabilitation and secondary prevention: A scientific statement from the Association of Cardiovascular Nursing and Allied Professions, European Association of Preventive Cardiology, and International Council of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 2515–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, E.A.; Berman, M.A.; Conlin, L.K.; Rehm, H.L.; Francey, L.J.; Deardorff, M.A.; Holst, J.; Kaur, M.; Gallant, E.; Clark, D.M.; et al. PECONPI: A novel software for uncovering pathogenic copy number variations in non-syndromic sensorineural hearing loss and other genetically heterogeneous disorders. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2013, 161A, 2134–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pack, Q.R.; Goel, K.; Lahr, B.D.; Greason, K.L.; Squires, R.W.; Lopez-Jimenez, F.; Zhang, Z.; Thomas, R.J. Participation in cardiac rehabilitation and survival after coronary artery bypass graft surgery: A community-based study. Circulation 2013, 128, 590–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escaned, J.; Cortes, J.; Flores, A.; Goicolea, J.; Alfonso, F.; Hernandez, R.; Fernandez-Ortiz, A.; Sabate, M.; Banuelos, C.; Macaya, C. Importance of diastolic fractional flow reserve and dobutamine challenge in physiologic assessment of myocardial bridging. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2003, 42, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ski, C.F.; Thompson, D.R.; Jackson, A.C.; Pedersen, S.S. Psychological screening in cardiovascular care. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2025, 24, 647–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ski, C.F.; Taylor, R.S.; McGuigan, K.; Long, L.; Lambert, J.D.; Richards, S.H.; Thompson, D.R. Psychological interventions for depression and anxiety in patients with coronary heart disease, heart failure or atrial fibrillation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2024, 4, CD013508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balady, G.J.; Ades, P.A.; Bittner, V.A.; Franklin, B.A.; Gordon, N.F.; Thomas, R.J.; Tomaselli, G.F.; Yancy, C.W.; American Heart Association Science, A.; Coordinating, C. Referral, enrollment, and delivery of cardiac rehabilitation/secondary prevention programs at clinical centers and beyond: A presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2011, 124, 2951–2960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, C.A. Is there something special about ischemic heart disease in patients undergoing dialysis? Am. Heart J. 2004, 147, 942–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheifer, S.E.; Rathore, S.S.; Gersh, B.J.; Weinfurt, K.P.; Oetgen, W.J.; Breall, J.A.; Schulman, K.A. Time to presentation with acute myocardial infarction in the elderly: Associations with race, sex, and socioeconomic characteristics. Circulation 2000, 102, 1651–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedland, K.E.; Skala, J.A.; Carney, R.M.; Rubin, E.H.; Lustman, P.J.; Davila-Roman, V.G.; Steinmeyer, B.C.; Hogue, C.W., Jr. Treatment of depression after coronary artery bypass surgery: A randomized controlled trial. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2009, 66, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, A.; Brugnera, A.; Adorni, R.; D’Addario, M.; Fattirolli, F.; Franzelli, C.; Giannattasio, C.; Maloberti, A.; Zanatta, F.; Steca, P. Protein Intake and Physical Activity in Newly Diagnosed Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome: A 5-Year Longitudinal Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennison Himmelfarb, C.R.; Beckie, T.M.; Allen, L.A.; Commodore-Mensah, Y.; Davidson, P.M.; Lin, G.; Lutz, B.; Spatz, E.S.; American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing. Shared Decision-Making and Cardiovascular Health: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023, 148, 912–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hess, E.P.; Coylewright, M.; Frosch, D.L.; Shah, N.D. Implementation of shared decision making in cardiovascular care: Past, present, and future. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2014, 7, 797–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Hooft, S.M.; Been-Dahmen, J.M.J.; Ista, E.; van Staa, A.; Boeije, H.R. A realist review: What do nurse-led self-management interventions achieve for outpatients with a chronic condition? J. Adv. Nurs. 2017, 73, 1255–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglis, S.C.; Clark, R.A.; McAlister, F.A.; Stewart, S.; Cleland, J.G. Which components of heart failure programmes are effective? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the outcomes of structured telephone support or telemonitoring as the primary component of chronic heart failure management in 8323 patients: Abridged Cochrane Review. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2011, 13, 1028–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaarsma, T.; Stromberg, A.; Martensson, J.; Dracup, K. Development and testing of the European Heart Failure Self-Care Behaviour Scale. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2003, 5, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durante, A.; De Maria, M.; Boyne, J.; Jaarsma, T.; Juarez-Vela, R.; Stromberg, A.; Vellone, E. Development and psychometric testing of the European Heart Failure Self-Care behaviour scale caregiver version (EHFScB-C). Patient Educ. Couns. 2021, 104, 2106–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwood, A.; Blumenthal, J.A.; Hinderliter, A.L.; Koch, G.G.; Adams, K.F., Jr.; Dupree, C.S.; Bensimhon, D.R.; Johnson, K.S.; Trivedi, R.; Bowers, M.; et al. Worsening depressive symptoms are associated with adverse clinical outcomes in patients with heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011, 57, 418–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, B.; Moser, D.K.; Pelter, M.M.; Nesbitt, T.S.; Dracup, K. Changes in Depressive Symptoms and Mortality in Patients With Heart Failure: Effects of Cognitive-Affective and Somatic Symptoms. Psychosom. Med. 2015, 77, 798–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czar, M.L.; Engler, M.M. Perceived learning needs of patients with coronary artery disease using a questionnaire assessment tool. Heart Lung 1997, 26, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, S.I.; Mattera, J.A.; Curtis, J.P.; Spertus, J.A.; Herrin, J.; Lin, Z.; Phillips, C.O.; Hodshon, B.V.; Cooper, L.S.; Krumholz, H.M. Telemonitoring in patients with heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 2301–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albert, N.M. Improving medication adherence in chronic cardiovascular disease. Crit. Care Nurse 2008, 28, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visco, V.; Forte, M.; Giallauria, F.; D’Ambrosio, L.; Piccoli, M.; Schiattarella, G.G.; Mancusi, C.; Salerno, N.; Cesaro, A.; Perrone, M.A.; et al. Epigenetic mechanisms underlying the beneficial effects of cardiac rehabilitation. An overview from the working groups of “cellular and molecular biology of the heart” and “cardiac rehabilitation and cardiovascular prevention” of the Italian Society of Cardiology (SIC). Int. J. Cardiol. 2025, 429, 133166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garofano, M.; Vecchione, C.; Calabrese, M.; Rusciano, M.R.; Visco, V.; Granata, G.; Carrizzo, A.; Galasso, G.; Bramanti, P.; Corallo, F.; et al. Technological Developments, Exercise Training Programs, and Clinical Outcomes in Cardiac Telerehabilitation in the Last Ten Years: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visco, V.; Esposito, C.; Rispoli, A.; Di Pietro, P.; Izzo, C.; Loria, F.; Di Napoli, D.; Virtuoso, N.; Bramanti, A.; Manzo, M.; et al. The favourable alliance between CardioMEMS and levosimendan in patients with advanced heart failure. ESC Heart Fail. 2024, 11, 2835–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Z.; Fan, Y.; Gong, X.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Li, X.; Fan, Z.; Han, Y. Adherence to phase I cardiac rehabilitation in post-PCI patients: A latent class analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 12, 1460855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampieron, A.; Aldo, S.; Corso, M. A retrospective study of nursing diagnoses, outcomes, and interventions for patients admitted to a cardiology rehabilitation unit. Int. J. Nurs. Terminol. Classif. 2011, 22, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dibben, G.O.; Faulkner, J.; Oldridge, N.; Rees, K.; Thompson, D.R.; Zwisler, A.D.; Taylor, R.S. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease: A meta-analysis. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 452–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Musharaf, S.; Aljuraiban, G.S.; Danish Hussain, S.; Alnaami, A.M.; Saravanan, P.; Al-Daghri, N. Low Serum Vitamin B12 Levels Are Associated with Adverse Lipid Profiles in Apparently Healthy Young Saudi Women. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.Y.L.; Wong, A.K.C.; Hung, T.T.M.; Yan, J.; Yang, S. Nurse-led Telehealth Intervention for Rehabilitation (Telerehabilitation) Among Community-Dwelling Patients With Chronic Diseases: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e40364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, H.C. Education and training towards competency for cardiac rehabilitation nurses in the United Kingdom. J. Clin. Nurs. 2000, 9, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Core components of cardiac rehabilitation/secondary prevention programs: 2007 update. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2007, 22, 425–426. [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, B.A. Home cardiac rehabilitation for congestive heart failure: A nursing case management approach. Rehabil. Nurs. 1999, 24, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettinardi, O.; da Vico, L.; Pierobon, A.; Iannucci, M.; Maffezzoni, B.; Borghi, S.; Ferrari, M.; Brazzo, S.; Mazza, A.; Sommaruga, M.; et al. First definition of minimal care model: The role of nurses, physiotherapists, dietitians and psychologists in preventive and rehabilitative cardiology. Monaldi Arch. Chest Dis. 2014, 82, 122–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Iannicelli, A.M.; De Matteo, P.; Vito, D.; Pellecchia, E.; Dodaro, C.; Giallauria, F.; Vigorito, C. Use of the North American Nursing Diagnosis Association taxonomies, Nursing Intervention Classification, Nursing Outcomes Classification and NANDA-NIC-NOC linkage in cardiac rehabilitation. Monaldi Arch. Chest Dis. 2019, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, B.; Fonarow, G.C.; Goldberg, L.R.; Guglin, M.; Josephson, R.A.; Forman, D.E.; Lin, G.; Lindenfeld, J.; O’Connor, C.; Panjrath, G.; et al. Cardiac Rehabilitation for Patients With Heart Failure: JACC Expert Panel. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 77, 1454–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.S.; Sagar, V.A.; Davies, E.J.; Briscoe, S.; Coats, A.J.; Dalal, H.; Lough, F.; Rees, K.; Singh, S. Exercise-based rehabilitation for heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, L.; Mordi, I.R.; Bridges, C.; Sagar, V.A.; Davies, E.J.; Coats, A.J.; Dalal, H.; Rees, K.; Singh, S.J.; Taylor, R.S. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for adults with heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Parashar, A.; Kumbhani, D.; Agarwal, S.; Garg, J.; Kitzman, D.; Levine, B.; Drazner, M.; Berry, J. Exercise training in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: Meta-analysis of randomized control trials. Circ. Heart Fail. 2015, 8, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaf, K.; Johnell, K.; Austin, P.C.; Tyden, P.; Midlov, P.; Perez-Vicente, R.; Merlo, J. Low adherence to statin treatment during the 1st year after an acute myocardial infarction is associated with increased 2nd-year mortality risk-an inverse probability of treatment weighted study on 54 872 patients. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacother. 2021, 7, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Zhou, X.; Ma, L.L.; Sun, T.W.; Bishop, L.; Gardiner, F.W.; Wang, L. A nurse-led structured education program improves self-management skills and reduces hospital readmissions in patients with chronic heart failure: A randomized and controlled trial in China. Rural. Remote Health 2019, 19, 5270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caru, M.; Curnier, D.; Bousquet, M.; Kern, L. Evolution of depression during rehabilitation program in patients with cardiovascular diseases. Disabil. Rehabil. 2020, 42, 378–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, S.H.; Anderson, L.; Jenkinson, C.E.; Whalley, B.; Rees, K.; Davies, P.; Bennett, P.; Liu, Z.; West, R.; Thompson, D.R.; et al. Psychological interventions for coronary heart disease: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2018, 25, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwingshackl, L.; Chaimani, A.; Schwedhelm, C.; Toledo, E.; Punsch, M.; Hoffmann, G.; Boeing, H. Comparative effects of different dietary approaches on blood pressure in hypertensive and pre-hypertensive patients: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 2674–2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin-Pelaez, S.; Fito, M.; Castaner, O. Mediterranean Diet Effects on Type 2 Diabetes Prevention, Disease Progression, and Related Mechanisms. A Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Mota, A.; Flores-Jurado, Y.; Norwitz, N.G.; Feldman, D.; Pereira, M.A.; Danaei, G.; Ludwig, D.S. Increased low-density lipoprotein cholesterol on a low-carbohydrate diet in adults with normal but not high body weight: A meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 119, 740–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colbert, G.B.; Venegas-Vera, A.V.; Lerma, E.V. Utility of telemedicine in the COVID-19 era. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 21, 583–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuan, P.X.; Chan, W.K.; Fern Ying, D.K.; Rahman, M.A.A.; Peariasamy, K.M.; Lai, N.M.; Mills, N.L.; Anand, A. Efficacy of telemedicine for the management of cardiovascular disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Digit. Health 2022, 4, e676–e691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mampuya, W.M. Cardiac rehabilitation past, present and future: An overview. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2012, 2, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnani, J.W.; Mujahid, M.S.; Aronow, H.D.; Cene, C.W.; Dickson, V.V.; Havranek, E.; Morgenstern, L.B.; Paasche-Orlow, M.K.; Pollak, A.; Willey, J.Z.; et al. Health Literacy and Cardiovascular Disease: Fundamental Relevance to Primary and Secondary Prevention: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018, 138, e48–e74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahsavari, H.; Shahriari, M.; Alimohammadi, N. Motivational factors of adherence to cardiac rehabilitation. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2012, 17, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Daly, J.; Sindone, A.P.; Thompson, D.R.; Hancock, K.; Chang, E.; Davidson, P. Barriers to participation in and adherence to cardiac rehabilitation programs: A critical literature review. Prog. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2002, 17, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGrady, A.; McGinnis, R.; Badenhop, D.; Bentle, M.; Rajput, M. Effects of depression and anxiety on adherence to cardiac rehabilitation. J. Cardiopulm. Rehabil. Prev. 2009, 29, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widmer, R.J.; Collins, N.M.; Collins, C.S.; West, C.P.; Lerman, L.O.; Lerman, A. Digital health interventions for the prevention of cardiovascular disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2015, 90, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Jia, X.; Li, J.; Mei, Z.; Yang, L.; Yan, C.; Han, Y. Efficacy and Safety of Hybrid Comprehensive Telerehabilitation (HCTR) for Cardiac Rehabilitation in Patients with Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Occup. Ther. Int. 2023, 2023, 5147805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lenarda, A.; Casolo, G.; Gulizia, M.M.; Aspromonte, N.; Scalvini, S.; Mortara, A.; Alunni, G.; Ricci, R.P.; Mantovan, R.; Russo, G.; et al. ANMCO/SIC/SIT Consensus document: The future of telemedicine in heart failure. G. Ital. Cardiol. 2016, 17, 491–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ades, P.A. Cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 892–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Phase | Description | Role of Cardiovascular Nurses 3 |

|---|---|---|

| Phase I (Acute) | Begins in the hospital post-cardiac event. Focuses on early mobilization, risk assessment, and education. | Monitor vital signs, assess risk factors, educate patients on lifestyle changes, and provide emotional support. |

| Phase II (Subacute) | Early outpatient phase, involving supervised exercise and lifestyle modification. Lasts 3–6 weeks. | Guide exercise therapy, ensure medication adherence, monitor psychological well-being, and provide dietary counseling. |

| Phase IIII (Maintenance) | Long-term rehabilitation focusing on sustained lifestyle changes, physical activity, and self-management. | Encourage long-term adherence to healthy behaviors, support mental health, and facilitate community-based interventions. |

| Phase IV (Long-term Prevention) | Ongoing self-management for high-risk patients to prevent disease progression. | Advocate for continued education, remote monitoring, and integration of digital health tools like telemedicine. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Izzo, C.; Visco, V.; Loria, F.; Squillante, A.; Iannarella, C.; Guerriero, A.; Cirillo, A.; Barbato, M.G.; Ferrigno, O.; Augusto, A.; et al. Cardiovascular Nursing in Rehabilitative Cardiology: A Review. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2025, 12, 219. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd12060219

Izzo C, Visco V, Loria F, Squillante A, Iannarella C, Guerriero A, Cirillo A, Barbato MG, Ferrigno O, Augusto A, et al. Cardiovascular Nursing in Rehabilitative Cardiology: A Review. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease. 2025; 12(6):219. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd12060219

Chicago/Turabian StyleIzzo, Carmine, Valeria Visco, Francesco Loria, Antonio Squillante, Chiara Iannarella, Antonio Guerriero, Alessandra Cirillo, Maria Grazia Barbato, Ornella Ferrigno, Annamaria Augusto, and et al. 2025. "Cardiovascular Nursing in Rehabilitative Cardiology: A Review" Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease 12, no. 6: 219. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd12060219

APA StyleIzzo, C., Visco, V., Loria, F., Squillante, A., Iannarella, C., Guerriero, A., Cirillo, A., Barbato, M. G., Ferrigno, O., Augusto, A., Rusciano, M. R., Virtuoso, N., Venturini, E., Di Pietro, P., Carrizzo, A., Vecchione, C., & Ciccarelli, M. (2025). Cardiovascular Nursing in Rehabilitative Cardiology: A Review. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease, 12(6), 219. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd12060219