Systematic Review of Methods Used for Food Pairing with Coffee, Tea, Wine, and Beer

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Aim

1.2. Limitations

2. Method

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Screening

2.4. Data Extraction

3. Results

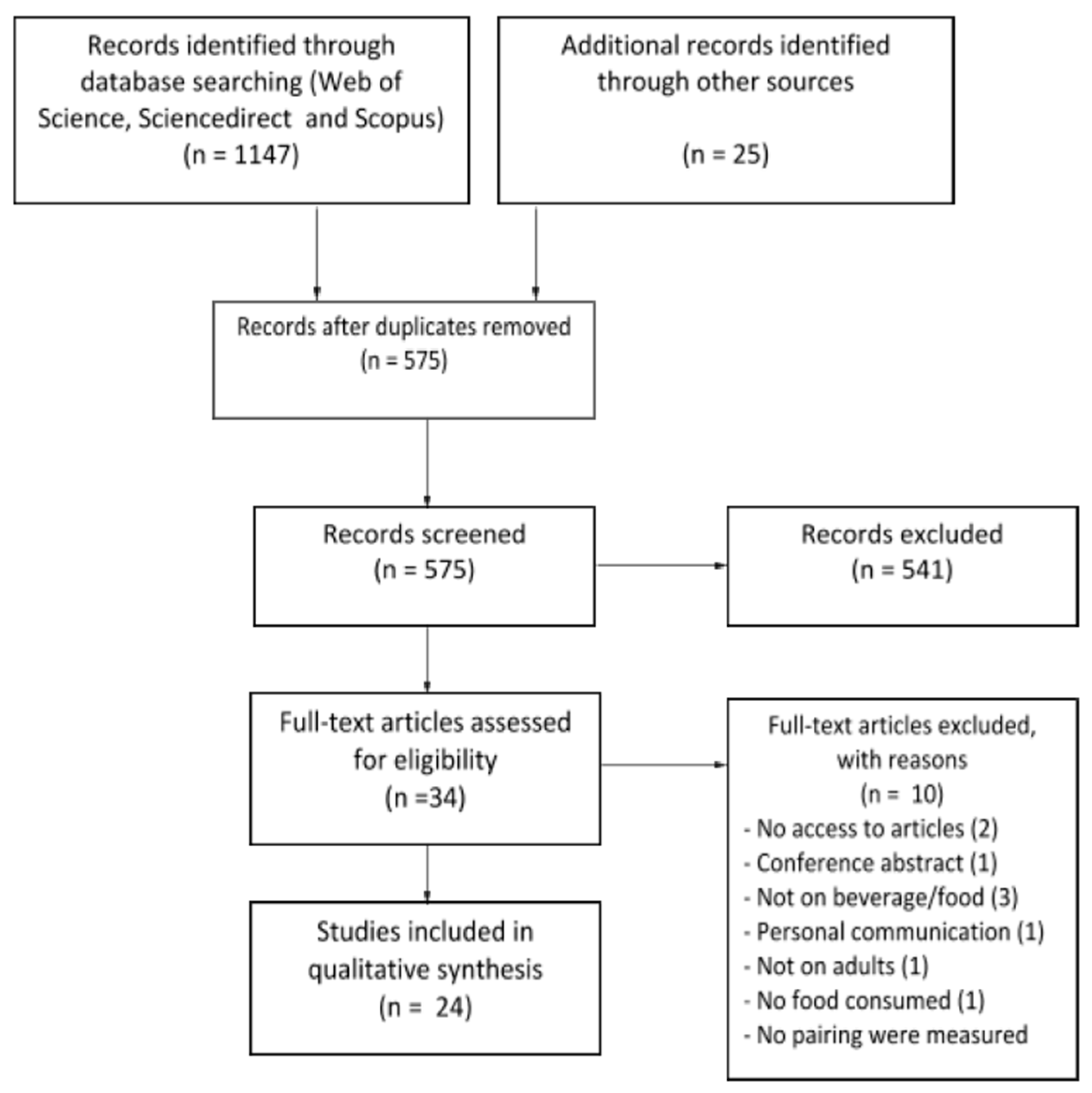

3.1. Selection of Articles and Studies

3.2. The Findings in the Articles

3.3. Food and Beverage Selection Criteria

3.4. The Evaluation Methods

3.4.1. Panel and/or Consumers to Evaluate the Beverage–Food Pairings

3.4.2. Measurements and Scale Use

3.5. The Tasting Methods

3.6. Sum of the Main Outcome

4. Discussion in Relevance to Further Studies

5. Conclusions in Relevance to Further Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lahne, J. Evaluation of Meals and Food Pairing. In Methods in Consumer Research; Ares, G., Varela, P., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2018; Volume 2, pp. 85–107. ISBN 9780081017432. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, Y.-Y.; Ahnert, S.E.; Bagrow, J.P.; Barabási, A.-L. Flavor network and the principles of food pairing. Sci. Rep. 2011, 1, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Klepper, M. Food Pairing Theory: A European Fad. Gastronomica 2011, 11, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eschevins, A.; Giboreau, A.; Julien, P.; Dacremont, C. From expert knowledge and sensory science to a general model of food and beverage pairing with wine and beer. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2019, 17, 100144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, C. Food and beverage flavour pairing: A critical review of the literature. Food Res. Int. 2020, 133, 109124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terrier, L.; Jaquinet, A.-L. Food–Wine Pairing Suggestions as a Risk Reduction Strategy. Psychol. Rep. 2016, 119, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, R.J.; Hammond, R. The Direct Effects of Wine and Cheese Characteristics on Perceived Match. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2005, 8, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, S.; Charters, S. Consumers’ expectations of food and alcohol pairing. Br. Food J. 2006, 108, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, L. How to Pair Coffee with Food. Available online: https://www.thespruceeats.com/pairing-coffee-and-food-765585 (accessed on 16 August 2019).

- Maxespresso Coffee and Dessert: The Perfect Pairing. Available online: http://www.maxespressocoffee.com/en/coffee-and-dessert-the-perfect-pairing/ (accessed on 16 August 2019).

- Jocelyn Girl Scout Cookies & Coffee Pairings. Available online: http://themodernbarista.com/index.php/2017/03/06/girl-scout-cookies-coffee-pairings/ (accessed on 16 August 2019).

- Coghlan, M. Pairings: Coffee and Cheese. Available online: https://www.freshcup.com/coffee-and-cheese/ (accessed on 16 August 2019).

- LeMay, S. Coffee Pairings. Available online: https://www.northstarroast.com/coffee-pairing/ (accessed on 16 August 2019).

- Shamseer, L.; Moher, D.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. BMJ Br. Med. J. 2015, 349, g7647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donadini, G.; Fumi, M.D.; Lambri, M. The hedonic response to chocolate and beverage pairing: A preliminary study. Food Res. Int. 2012, 48, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donadini, G.; Fumi, M. An investigation on the appropriateness of chocolate to match tea and coffee. Food Res. Int. 2014, 63, 464–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Kinugasa, H. Influence of Japanese green tea on the Koku attributes of bonito stock: Proposed basic rules of pairing Japanese green tea with Washoku. J. Sens. Stud. 2019, 34, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nygren, I.; Gustafsson, I.; Haglund, Å.; Johansson, L.; Noble, A. Flavor changes produced by wine and food interactions: Chardonnay wine and hollandaise sauce. J. Sens. Stud. 2001, 16, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nygren, I.T.; Gustafsson, I.-B.; Johansson, L. Perceived flavour changes in white wine after tasting blue mould cheese. Food Serv. Technol. 2002, 2, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nygren, I.T.; Gustafsson, I.-B.; Johansson, L. Perceived flavour changes in blue mould cheese after tasting white wine. Food Serv. Technol. 2003, 3, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, M.; Cliff, M. Evaluation of ideal wine and cheese pairs using a deviation-from-ideal scale with food and wine experts. J. Food Qual. 2005, 28, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, R.J.; Hammond, R. Body Deviation-from-Match. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2006, 5, 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrigal-Galan, B.; Heymann, H. Sensory effects of consuming cheese prior to evaluating red wine flavor. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2006, 57, 12–22. [Google Scholar]

- Bastian, S.; Payne, C.; Perrenoud, B.; Joscelyne, V.; Johnson, T. Comparisons between Australian consumers’ and industry experts’ perceptions of ideal wine and cheese combinations. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2009, 15, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastian, S.E.; Collins, C.; Johnson, T.E. Understanding consumer preferences for Shiraz wine and Cheddar cheese pairings. Food Qual. Prefer. 2010, 21, 668–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, R.J.; McCarthy, M.; Gozzi, M. Perceived Match of Wine and Cheese and the Impact of Additional Food Elements: A Preliminary Study. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2010, 13, 311–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, R.J.; Seo, H.-S. The Impact of Liking of Wine and Food Items on Perceptions of Wine–Food Pairing. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2015, 18, 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koone, R.; Harrington, R.J.; Gozzi, M.; McCarthy, M. The role of acidity, sweetness, tannin and consumer knowledge on wine and food match perceptions. J. Wine Res. 2014, 25, 158–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galmarini, M.V.; Loiseau, A.-L.; Visalli, M.; Schlich, P. Use of Multi-Intake Temporal Dominance of Sensations (TDS) to Evaluate the Influence of Cheese on Wine Perception. J. Food Sci. 2016, 81, S2566–S2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galmarini, M.V.; Debreyer, D.; Visalli, M.; Schlich, P.; Loiseau, A.-L. Use of Multi-Intake Temporal Dominance of Sensations (TDS) to Evaluate the Influence of Wine on Cheese Perception. J. Food Sci. 2017, 82, 2669–2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nygren, T.; Nilsen, A.N.; Öström, Å. Dynamic changes of taste experiences in wine and cheese combinations. J. Wine Res. 2017, 28, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galmarini, M.V.; Dufau, L.; Loiseau, A.-L.; Visalli, M.; Schlich, P. Wine and Cheese: Two Products or One Association? A New Method for Assessing Wine-Cheese Pairing. Beverages 2018, 4, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donadini, G.; Spigno, G.; Fumi, M.D.; Pastori, R. Evaluation of Ideal Everyday Italian Food and Beer Pairings with Regular Consumers and Food and Beverage Experts. J. Inst. Brew. 2008, 114, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donadini, G.; Fumi, M.D.; Lambri, M. A preliminary study investigating consumer preference for cheese and beer pairings. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 30, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donadini, G.; Fumi, M.; Newby-Clark, I. An investigation of matches of bottom fermented red beers with cheeses. Food Res. Int. 2015, 67, 376–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulsen, M.T.; Rognså, G.H.; Hersleth, M. Consumer perception of food–beverage pairings: The influence of unity in variety and balance. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2015, 2, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eschevins, A.; Giboreau, A.; Allard, T.; Dacremont, C. The role of aromatic similarity in food and beverage pairing. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 65, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nygren, I.T.; Gustafsson, I.; Johansson, L. Effects of tasting technique–sequential tasting vs. mixed tasting–on perception of dry white wine and blue mould cheese. Food Serv. Technol. 2003, 3, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineau, N.; Schlich, P.; Cordelle, S.; Mathonnière, C.; Issanchou, S.; Imbert, A.; Rogeaux, M.; Etiévant, P.; Köster, E. Temporal Dominance of Sensations: Construction of the TDS curves and comparison with time–intensity. Food Qual. Prefer. 2009, 20, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenthal, H. The Fat Duck Cookbock; Bloomsbury Puplishing Plc: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Keast, R.S.J.; Breslin, P.A.S. An overview of binary taste–taste interactions. Food Qual. Prefer. 2003, 14, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niimi, J.; Eddy, A.I.; Overington, A.R.; Heenan, S.P.; Silcock, P.; Bremer, P.J.; Delahunty, C.M. Aroma–taste interactions between a model cheese aroma and five basic tastes in solution. Food Qual. Prefer. 2014, 31, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PICOS | Study Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Population: | Participants had to be performed on adults |

| Intervention: | The intervention had to apply a form of a pairing of a beverage and a food item |

| Comparison: | Not possible |

| Outcomes: | The outcomes were measured on a hedonic Likert scale, a line scale, a JAR or modified JAR scale, or other relevant scale measurement methods for the given attribute |

| Study design: | The intervention had to be based on an experimental design, a descriptive analysis (DA), or a consumer study |

| Authors | Food and Beverage | Why and Selection Criteria | Tasting Method | N Participants | Method and Scale Use | Main Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COFFEE/TEA | ||||||

| [15] | 3 chocolate vs. 18 beverage | To create a general recommendation. Chocolate with differing cacao %. Focus group selected beverages. | mixed | n = 14 (experienced assessors) n = 80 (regular chocolate consumers) | Sensory: DA on chocolate and beverages. Intensity rating of attributes on 9-point anchored scales. Hedonic: Liking of chocolate and beverage individually rated on a 9-point hedonic Likert scale. Dominance or match on the pairings using a JAR 12 cm line-scale. | The chocolate/beverage pair liking depended more on the beverage liking than the chocolate liking and the level of the match. |

| [16] | 3 coffee, 4 tea vs. 3 chocolate | Coffee/tea match for chocolate. | mixed | n = 8 (experienced assessors) n = 80 (regular chocolate consumers) | Sensory: DA on chocolate and beverages. Intensity rating of attributes on 9-point anchored scales. Hedonic: Liking of chocolate and beverage individually rated on a 9-point hedonic Likert scale. Dominance or match on the pairings using a JAR 12 cm line-scale. | When chocolate/beverage pairing was balanceed, it was perferred by consumers. With one of the two dominating the pairing, there was a decrease in acceptance, and most when chocolate dominated. A liked chocolate and a liked beverage do not score high in pair liking. |

| [17] | 2 green tea vs. 1 soup (bonito stock) | The influence of green tea on the sensory perception of Japanese food. | sequential temporal dominance of sensations (TDS) | n = 16 (trained assessors) n = 12 (trained assessors) | Sensory: DA on the intensity of the koku attributes of the soup 10 cm line scale after the influence of the soup. TDS: Evacuation of the attribute dominance of the attributes found in the soup. | The green tea enhanced Koku attributes (thickness, continuity, mouthfulness, and umami intensity). However, it was suppressed when the tea was too astringent. Green tea changed the dominant perception of the soup attributes. |

| WINE | ||||||

| [18] | 2 hollandaise sauce vs. 3 chardonnay | Based on a previous study on the sauce. | sequential | n = 10 (students were trained) | Sensory: DA on wine and sauce. The intensity of the describing wine and sauce attributes were rated in triplicate to measure the effect of sauce on wine and wine on the sauce, using a 100-point scale | The effect of sauce on wine was more significant. |

| [19] | 5 dry white wines vs. 2 blue cheese | Unusual combination. The cheese was local, and wine was chosen from a dry wine assortment. | sequential | n = 9 (trained assessors) | Sensory: DA on wine and cheese. The intensity of the describing wine and cheese attributes were rated in triplicates to measure the effect of cheese on wine (wine–cheese–wine), using a 100-point scale. | Most of the attributes of the wines studied, such as apple, citrus, and oak flavors, and sour taste, decreased, whereas others remained unchanged. |

| [20] | 2 blue cheese vs. 5 dry white wines | Unusual combination. The cheese was local, and wine was chosen from a dry wine assortment. | sequential | n = 9 (trained assessors) | Sensory: DA on wine and cheese. The intensity of the describing wine and cheese attributes were rated in triplicates to measure the effect of wine on cheese (cheese–wine–cheese) using a 100 point scale. | Most of the pronounced characteristics of the two blue mold cheeses, such as the buttery, woolly, and basement-like flavors of one cheese and the sourness and saltiness of the other, scored lower after the tasting of dry white wine. |

| [21] | 9 cheeses vs. 18 wines (6 white, 6 red, and 6 specialty wines) | This paring dates back to 6000 BC. Award-winning cheese and wine selected by a wine expert. | mixed | n = 27 (8 restaurateurs and 19 wine industry personnel) | The judges evaluated the pairing to find a match or a domination wine/cheese using a JAR 12 cm line-scale. | Wine and cheese are comparable food pairings. A little better with white wine with the used cheeses. The stronger, more flavorful cheeses were more difficult to pair with the wines but were more likely to be a good match for the late harvest and ice wines than other milder cheeses. |

| [7] | 6 wines vs. 4 cheeses | Wine selection due to variety on quality and cheese represented different types. | sequential and mixed | n = 13 (trained panel of undergraduate students and faculty) | DA: characteristics: Wine: color, taste, texture, and other aspects. Cheese: level of the key components, texture, and flavors. This was measured individual on a 6.7 cm continuous scale. Then, the level of the match (mixed) was measured on a 9-point scale (1 = no match, 9 = synergistic match). | The overall level of sweetness in wine impacted the perceived match across all cheeses. Additional relationships varied by cheese. The impact of the food elements present in four cheese types and the match for the six wines were non-significant in the overall test. Significant relationships were shown for cheese sweetness level, spiciness level, and the overall body of the cheese. |

| [22] | 4 wines vs. 3 dishes (chicken, pork, beef) | Different levels of the match, body to body match. Wine: different levels of tannins and body. Food: different levels of fattiness and body. | sequential and mixed | n = 8 (members of a trained panel) | DA: Wines: level of tannin, alcohol, and body. Foods: level of fattiness and body. This was measured individual on a 6.7 cm line-scale. Level of the match ranked on a 9-point scale. Mixed body deviation from the match, ranked from +4 to −4 (+4 food and −4 wine dominated). Sequential body deviation from the match and food fattiness minus tannins were both measured on a 6.7 cm line scale. | Body to body match is a significant predictor of the overall predicted match. The sequential method was a significant predictor of the overall predicted match. |

| [23] | 8 wines vs. 8 cheeses | Wine flavor is influenced by a variety of cheeses. Wine: different varieties. Cheese: soft, medium, hard, and blue. | sequential | n = 11 (students—was trained) | DA: Describing terms of wine. Intensity measurements of the attributes using a 10 cm unstructured line scale unanchored. (wine–cheese–wine). | The cheese had a significant effect on red wine flavor. Astringency, bell pepper, and oak flavor decreased, and the butter flavor increased by cheese. |

| [24] | 7 wines vs. 8 chesses | Evaluation of wine and cheese combination, suggested by industry experts. | mixed | n = 46 (wine and cheese consumers) | The consumers evaluated the ideal pairing using a JAR 12 cm line scale using. | Consumers agreed with an expert on six out of eight pairings. |

| [25] | 10 shiraz vs. 1 cheddar cheese | To find the best shiraz match to one cheddar cheese. | mixed | n = 7 (assessors) n = 54 (wine and cheese consumers) n = 22 (wine experts) | DA: of the wine properties. Attributes were intensity rated on an unstructured 15 cm line scale. Consumer and experts: evaluated the hedonic liking of the wines on a 15 cm Likert scale. Then, the match on a 12 cm JAR scale. Experts: also rated the wines on a 20-point quality scale. | Wine domination of the cheese did not appear to drive the preference for wine and cheese pairs; instead, it seemed driven by an overall preference for the wine alone. The consumer most liked pairing contained expert top quality rated wines, and the least liked pairings contained expert low quality rated wine. |

| [26] | 5 cheeses vs. 6 wines + 3 food elements | To find the impact of additional food on wine–cheese match perception. Based on expert matches. | sequential and mixed | n = 14 (industry professionals) | The pairings were evaluated on a 12 cm deviation from the match scale (JAR) in order to find whether the cheese or wine dominated or had a match. Both on the cheese/wine pairings and on the cheese/food/wine pairings. | The addition of food items generally improved the sensation of the match, and only in one pairing was it statistically lower. |

| [27] | 2 wines vs. 2 food items (goat cheese and chocolate) | To find match level perceptions of classic food–wine pairings against non-classical food–wine pairings. | not described | n = 79 (students) | The wine, food, and pairings were evaluated on a 9-point Likert scale. | Three of the four wine–food combinations had positive direct relationships among wine liking, food liking, or both on the liking level of the wine–food combination when tasted together. |

| [28] | 4 wines vs. 4 foods (goat cheese, brie, salami, and milk chocolate) | To find matches of different wines and food on the basis of the impact of wine sweetness, acidity, and tannin. To find the match based on expertise. | mixed | n = 248 (consumers with different level of wine expertise) | Each questing on the ideal match was rated at a 10 cm long line scale. Wines were evaluated from light to heavy with all foods (no further details on this). Then, there was an evaluation on a mixed tasting and answering the perception of the match. | Wine sweetness, acidity, and tannin levels all significantly impacted the level of match with certain food items. |

| [29] | 4 cheeses vs. 4 wines | The perception of the wine before and after cheese. Using comitial wine and cheese. | TDS | n = 31 (wine and cheese consumers) | Evaluation of the wine alone over three consecutive sips. The evaluation of the wine with consumption of cheese between the three sips. | How wine perception evolved over sips. Cheese intake in between wine sips changed the dynamic characterisation of wines. None of the four cheeses included in this study had a negative impact on wine liking. Liking of wine was either improved or remained the same after cheese intake. |

| [30] | 4 cheeses vs. 4 wines | The perception of the cheese before and after wine. Using comitial wine and cheese. | TDS | n = 31 (wine and cheese consumers) | Evaluation of the cheese alone over three consecutive bites. The evaluation of the cheese with consumption of wine between the three bites. | The impact of wine on cheese perception did not translate into changes in liking. Cheeses changed less from wine to wine than wines did from cheese to cheese. This would reveal that the choice of wine would be more critical when pairing cheese and wine because it is wine perception that is more likely to be changed. |

| [31] | 5 wine vs. 2 cheese | Explore wine and cheese liking and find match or domination—understanding of liking and dynamic taste experience. | TDS and mixed | n = 8 (students and staff) n = 45 (wine consumers) | Panel: TDS was measured on the cheese, wine, and the pairing in replicates. Consumer: At a restaurant setting. The cheese was served before dessert, during a five-course meal. They rated dominance on the JAR scale (+3 to −3), then pair liking on a hedonic 7 point scale. | The TDS evaluation method makes it possible to obtain dynamic information about the process of eating a meal and to understand more of the relationship between consumer liking and dynamic taste experience. |

| [32] | 3 wines vs. 3 cheeses | Find dominating attributes of the dynamic liking of cheese, wine, and the pairing. Same terroir products. | TDS and temporal drivers of liking (TDL) | n = 60 (consumer) | Cheese and wine were individually evaluated using mono-intake TDS and with hedonic liking (discrete 9-point hedonic scale). Then the combination was evaluated by multi-bite and multi-sip TDS. | Changes in the dynamic perception had a larger impact on the liking of wine compared to cheese. It was observed that the dynamic sensory perception had a more important impact on liking in wine–cheese combinations than when consumed separately. |

| BEER | ||||||

| [33] | 18 beer vs. 9 dishes of Italian cuisine | Characteristics of beer and food harmonically complement each other. Beer: availability and variety. Food: popular Italian dishes. | mixed | n = 7 (trained assessors) n = 51 (consumer) n = 7 (food experts) | DA: sensory profile of the beers and the dishes. Level of the match using a 9-point Likert scale of appropriateness. | Most of the dishes were poor complements to the beers selected for this study, but some interesting pairings were found. There was an ideal pair where the combination was more liked than the beer/food alone, and neither the beer nor food dominated. |

| [34] | 4 cheese vs. 4 beers | Hedonic response in natural consumption environment. Beer: different styles and most sold. Cheese: availability and different profiles. | mixed | n = 7 (trained assessors) n = 80 (beer and cheese consumers) | DA: sensory profile of cheese and bees alone and with one of the cheeses. Each beer and cheese and pair were scored on a 9-point hedonic scale. Each pairing was rated on a JAR to determine which flavor (beer/cheese) lingered the most. | Cheese/beer pairing preference depended on beer preference more than on cheese preference, cheese-type, beer type, and flavor dominance. |

| [35] | 8 beers vs. 7 cheeses | Hedonic response to beer and cheese pairings in the social environment and the effect of cheese on beer. Beer: most sold. Cheese: most eaten. | mixed | n = 8 (trained assessors) n = 96 (cheese and beer consumers) | DA: Beers: attributes were rated on a 9-point horizontal line. Cheese: attributes were rated on a 9-point line (different anchor words). Hedonic: Liking of beer and cheese individually and liking of the pairs on a 9-point hedonic Likert scale. | Consumers did not simply enjoy a combination of their most preferred beer and cheese. They identified some flavors that harmonise better than do others. Moreover, significant correlations between mean liking scores and sensory characteristics of the 56 pairings were found. The beer flavor was primarily modified by prior cheese consumption. Pairing liking was found to depend on the type of cheese. |

| [36] | DA: 2 beer vs. 6 soups; hedonic: 2 beer and 3 soups | Consumer liking of harmony, complexity, and balance of pairings. Basic taste as experimental factors. | mixed | n = NS (trained panel) n = 80 (students) | DA: on the beers and the soup and the pairings. Hedonic: liking, harmony, and complexity on 9-point scales with different anchor words. Balanced on a modified 5-point JAB scale to find a match or dominance. First on the beer and soup individual, then on the pairings. | The results demonstrated that perceived balance and the concept of “unity in variety” play essential roles in the consumer perception of pairings. Results from the consumer study showed significant effects of beer type on liking. |

| [37] | Lemon syrup soft drink and flavored dairy product + beers and savory verrines | Investigate how aromatic similarity modulates consumer judgment of pairings. | mixed | n = 53 n = 47 (both volunteer consumers) | Pairings were evaluated by first taking a sip of the drink, then a spoonful food product, and finally another sip of the drink and a spoonful of food product before assessing the liking, harmony, homogeneity, familiarity, and complexity. Balance was scored on a +3 to −3 scale and a +5 to −5 scale. The rest was scored on a 10 point scale. | The results demonstrate that aromatic similarity in food and beverage pairings modulates the levels of perceived harmony, homogeneity, and complexity of pairing. The liking of the individual food seems to be an influential determinant of pairing choices. However, aromatic similarity, by enhancing the perceived harmony and modulating perceived complexity, also contributes to the hedonic judgment of the pairing. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rune, C.J.B.; Münchow, M.; Perez-Cueto, F.J.A. Systematic Review of Methods Used for Food Pairing with Coffee, Tea, Wine, and Beer. Beverages 2021, 7, 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages7020040

Rune CJB, Münchow M, Perez-Cueto FJA. Systematic Review of Methods Used for Food Pairing with Coffee, Tea, Wine, and Beer. Beverages. 2021; 7(2):40. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages7020040

Chicago/Turabian StyleRune, Christina J. Birke, Morten Münchow, and Federico J. A. Perez-Cueto. 2021. "Systematic Review of Methods Used for Food Pairing with Coffee, Tea, Wine, and Beer" Beverages 7, no. 2: 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages7020040

APA StyleRune, C. J. B., Münchow, M., & Perez-Cueto, F. J. A. (2021). Systematic Review of Methods Used for Food Pairing with Coffee, Tea, Wine, and Beer. Beverages, 7(2), 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages7020040