Can Plant-Based Milk Alternatives Fully Replicate UHT Cow Milk? A Review of Sensory and Physicochemical Attributes

Abstract

1. Introduction

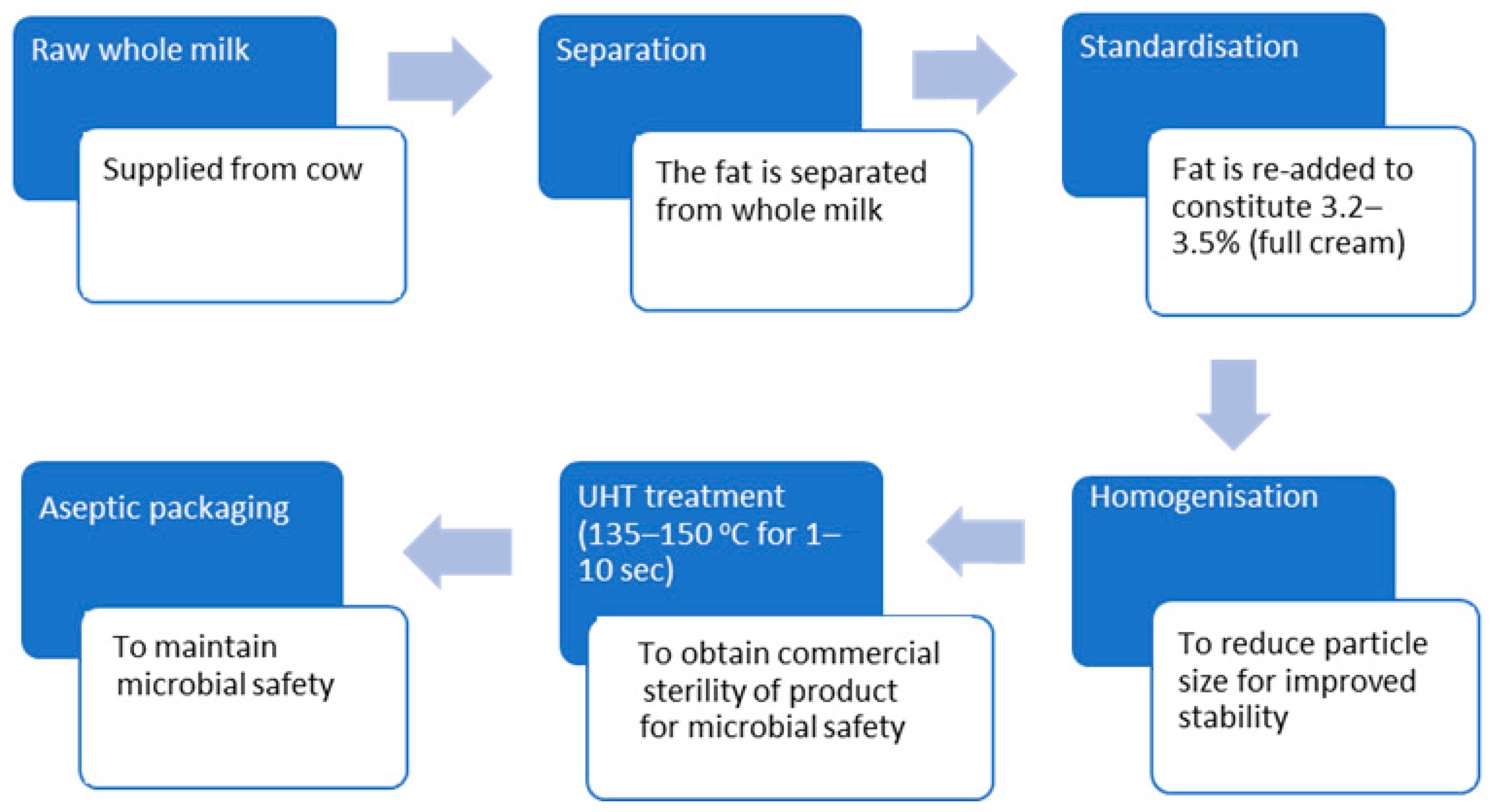

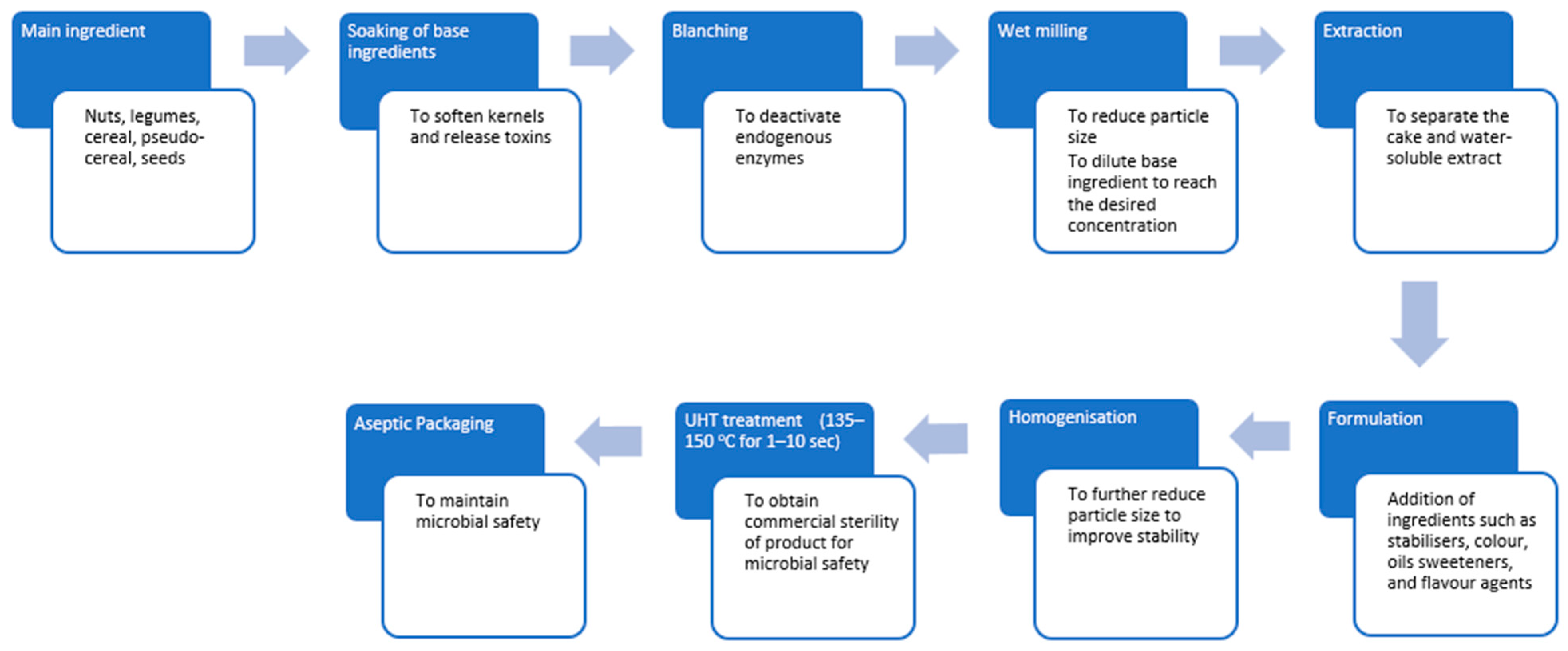

2. PBMA and Cow Milk Production Process

2.1. UHT Full Cream Cow Milk Production

2.2. PBMA Production

3. Chemical and Nutritional Composition

4. Sensory Attributes

4.1. Appearance

4.2. Texture and Mouthfeel

4.3. Flavour

| Milk Types | Volatile Compounds | Aroma Description | Volatile Extraction and Quantification Method | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Almond milk | Pyrazine, 2,3-dimethyl | Nutty | HS-SPME GC–MS; semi-quantitative | [77,103] |

| 1-hexanol, 2-ethyl- | Oily, sweet, floral | HS-SPME GC–MS; semi-quantitative | [12] | |

| Benzaldehyde | Almond, malt, woody, sweet | HS-SPME GC–MS; semi-quantitative | [12,32] | |

| Pyrazine, 2,6-dimethyl | Nutty | HS-SPME GC–MS; n/a | [32] | |

| Oat milk | Hexanal | Green, grassy | HS-SPME GC–MS; semi-quantitative | [41,87,91] |

| Dimethyl sulphide | Cabbage, sulphur, gasoline | HS-SPME GC–MS; semi-quantitative | [12] | |

| Furfural | Bready | HS-SPME GC–MS; semi-quantitative | [16] | |

| 2-methyl butanal | Cocoa | HS-SPME GC–MS; semi-quantitative | [16] | |

| 3-methyl butanal | Fruity | HS-SPME GC–MS; semi-quantitative | [16] | |

| Octanal | Soapy, citrusy | HS-SPME GC–MS; semi-quantitative | [84,87] | |

| 2-Pentyl furan | Fruity, fruity, green, beany, floral | HS-SPME GC–MS; semi-quantitative | [16,32] | |

| Soy milk | Hexanal | Green, grass, tallow, fat | HS-SPME GC–MS; semi-quantitative | [32,41,91] |

| 3-methyl-1-butanol | Banana, floral, fruity, malt, wheat | HS-SPME GC–MS; n/a | [32] | |

| 2-pentylfuran | Fruity, green | HS-SPME GC–MS; n/a | [32] | |

| Nonanal | Fat, citrus, green | HS-SPME GC–MS; semi-quantitative | [91,104] | |

| 1-octen-3-ol | Mushroom | HS-SPME GC–MS; semi-quantitative | [105] | |

| Acetic acid | Sour, fruity, vinegar | HS-SPME GC–MS; n/a | [32] | |

| UHT cow milk | 2-heptanone | Fruity, creamy | HS-SPME GC–MS; quantitative and semi-quantitative | [106] |

| Hydrogen sulphide | Eggy/ sulphur | HS-SPME GC–MS; quantitative | [22] | |

| Dimethyl sulphide | Cabbage, sulphur, gasoline | HS-SPME GC–MS; quantitative | [22,91] | |

| Benzaldehyde | Almond, burnt sugar, cooked, | HS-SPME GC–MS; quantitative | [22,91] | |

| Maltol | Sweet | HS-SPME GC–MS; quantitative | [22] | |

| 2-Nonanone | Sweet | HS-SPME GC–MS; quantitative and semi-quantitative | [106] | |

| Furfural | Barny/brothy | HS-SPME GC–MS; quantitative | [22] | |

| 1-Octen-3-ol | Mushroom | HS-SPME GC–MS; quantitative and semi-quantitative | [106] |

5. Challenges in Replicating the Sensory Properties of UHT Milk

5.1. Emulsion Dynamics

5.1.1. Plant Protein

5.1.2. Carbohydrates

5.1.3. Calcium

5.1.4. Fat

6. Bridging the Gap

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mekanna, A.N.; Issa, A.; Bogueva, D.; Bou-Mitri, C. Consumer perception of plant-based milk alternatives: Systematic review. Int. J. Food Sci. Tech. 2024, 59, 8796–8805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Milk Substitutes—Worldwide. Available online: https://www.statista.com/outlook/cmo/food/dairy-products-eggs/milk-substitutes/worldwide (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Sethi, S.; Tyagi, S.K.; Anurag, R.K. Plant-based milk alternatives an emerging segment of functional beverages: A review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 53, 3408–3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, H.; Kuchler, F.; Cessna, J.; Hahn, W. Are Plant-Based Analogues Replacing Cow’s Milk in the American Diet? J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 2020, 52, 562–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, P. Does plant-based milk reduce sales of dairy milk? Evidence from the almond milk craze. Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 2023, 52, 112–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, S.C.; Siow, L.F.; Lee, Y.Y. Identification of Sensory Drivers of Liking of Plant-Based Milk Using a Novel Palm Kernel Milk—The Effect of Reformulation and Flavors Addition Through CATA and PCA Analysis. Food Sci. Nutr. Curr. Issues Answ. 2025, 13, e4719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Jurado, F.; Soto-Reyes, N.; Dávila-Rodríguez, M.; Lorenzo-Leal, A.; Jiménez-Munguía, M.; Mani-López, E.; López-Malo, A. Plant-Based Milk Alternatives: Types, Processes, Benefits, and Characteristics. Food Rev. Int. 2023, 39, 2320–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsing, R.; Santo, R.; Kim, B.F.; Altema-Johnson, D.; Wooden, A.; Chang, K.B.; Semba, R.D.; Love, D.C. Dairy and Plant-Based Milks: Implications for Nutrition and Planetary Health. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2023, 10, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiné, R.P.F.; Florença, S.G.; Barroca, M.J.; Anjos, O. The Link between the Consumer and the Innovations in Food Product Development. Foods 2020, 9, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazzaro, C.; Stanco, M.; Uliano, A.; Marotta, G. Consumers’ acceptance and willingness to pay for enriched foods: Evidence from a choice experiment in Italy. Future Foods 2024, 10, 100405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeske, S.; Zannini, E.; Arendt, E.K. Evaluation of Physicochemical and Glycaemic Properties of Commercial Plant-Based Milk Substitutes. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2017, 72, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaikma, H.; Kaleda, A.; Rosend, J.; Rosenvald, S. Market mapping of plant-based milk alternatives by using sensory (RATA) and GC analysis. Future Foods 2021, 4, 100049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drewnowski, A. The Science and Complexity of Bitter Taste. Nutr. Rev. 2001, 59, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydar, E.F.; Tutuncu, S.; Ozcelik, B. Plant-based milk substitutes: Bioactive compounds, conventional and novel processes, bioavailability studies, and health effects. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 70, 103975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, R.; LeBlanc, J.; Gorman, M.; Ritchie, C.; Duizer, L.; McSweeney, M.B. A Prospective Review of the Sensory Properties of Plant-Based Dairy and Meat Alternatives with a Focus on Texture. Foods 2023, 12, 1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarron, R.; Methven, L.; Grahl, S.; Elliott, R.; Lignou, S. Oat-based milk alternatives: The influence of physical and chemical properties on the sensory profile. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1345371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Jia, Q.; Cui, L.; Dai, Y.; Li, R.; Tang, J.; Lu, J. Physical-Chemical and Sensory Quality of Oat Milk Produced Using Different Cultivars. Foods 2023, 12, 1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, B.; Shrivastav, A.; Das, T.; Goswami, T.K. Physicochemical and nutritional assessment of soy milk and soymilk products and comparative evaluation of their effects on blood gluco-lipid profile. Appl. Food Res. 2022, 2, 100146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.; Keast, R.; Liem, D.G.; Nolvachai, Y.; Costanzo, A. Impact of protein on sensory attributes and liking of plant-based Milk alternatives. Food Qual. Prefer. 2025, 133, 105617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Penaranda, A.V.; Reitmeier, C.A. Sensory Descriptive Analysis of Soymilk. J. Food Sci. 2001, 66, 352–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatih, M.; Barnett, M.P.G.; Gillies, N.A.; Milan, A.M. Heat Treatment of Milk: A Rapid Review of the Impacts on Postprandial Protein and Lipid Kinetics in Human Adults. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 643350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, Y.; Benoist, D.M.; Barbano, D.M.; Drake, M.A. Flavor and flavor chemistry differences among milks processed by high-temperature, short-time pasteurization or ultra-pasteurization. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 3812–3828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Keast, R.; Liem, D.G.; Jadhav, S.R.; Mahato, D.K.; Gamlath, S. Barista-Quality Plant-Based Milk for Coffee: A Comprehensive Review of Sensory and Physicochemical Characteristics. Beverages 2025, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezzetti, M.; Passamonti, M.M.; Dall’Asta, M.; Bertoni, G.; Trevisi, E.; Ajmone Marsan, P. Emerging Parameters Justifying a Revised Quality Concept for Cow Milk. Foods 2024, 13, 1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeth, H.C. Heat Treatment of Milk: Extended Shelf-Life (ESL) and Ultra-High Temperature (UHT) Treatments. In Encyclopedia of Dairy Sciences, 3rd ed.; McSweeney, P.L.H., McNamara, J.P., Eds.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2022; pp. 618–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food Standards Australia New Zealand. Australian Food Composition Database—Release 2.0. Available online: https://www.foodstandards.gov.au/science-data/food-nutrient-databases/afcd (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Ren, Q.; Li, Q.; Liu, H.; Ma, Y. Thermal and storage properties of milk fat globules treated with different homogenisation pressures. Int. Dairy J. 2020, 110, 104725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetra, P. UHT Treatment. Available online: https://www.tetrapak.com/en-anz/solutions/integrated-solutions-equipment/processing-equipment/uht-treatment (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Hummel, D.; Atamer, Z.; Butz, L.; Hinrichs, J. Reproducing high mechanical load during industrial processing of ultra-high-terature milk: Effect on frothing capacity. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107, 10452–10461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, M.A.; Langton, M.; Innings, F.; Malmgren, B.; Höjer, A.; Wikström, M.; Lundh, Å. Changes in stability and shelf-life of ultra-high temperature treated milk during long term storage at different temperatures. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, N.; Deeth, H.C. Age Gelation of UHT Milk—A Review. Food Bioprod. Process. 2001, 79, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pointke, M.; Albrecht, E.H.; Geburt, K.; Gerken, M.; Traulsen, I.; Pawelzik, E. A Comparative Analysis of Plant-Based Milk Alternatives Part 1: Composition, Sensory, and Nutritional Value. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocker, R.; Silva, E.K. Innovative technologies for manufacturing plant-based non-dairy alternative milk and their impact on nutritional, sensory and safety aspects. Future Foods 2022, 5, 100098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeske, S.; Bez, J.; Arendt, E.K.; Zannini, E. Formation, stability, and sensory characteristics of a lentil-based milk substitute as affected by homogenisation and pasteurisation. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2019, 245, 1519–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romulo, A. Food Processing Technologies Aspects on Plant-Based Milk Manufacturing: Review. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Sustainability Agriculture and Biosystem, Online, 24 November 2021; Volume 1059, p. 012064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, P.; Wang, T.; Luo, Y. A review on plant-based proteins from soybean: Health benefits and soy product development. J. Agric. Food Res. 2022, 7, 100265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; You, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, Z.; Yi, J.; Jin, G. Enhancing Functional Properties and Protein Structure of Almond Protein Isolate Using High-Power Ultrasound Treatment. Molecules 2024, 29, 3590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holopainen-Mantila, U.; Vanhatalo, S.; Lehtinen, P.; Sozer, N. Oats as a source of nutritious alternative protein. J. Cereal Sci. 2024, 116, 103862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Dong, R.; Hu, X.; Ren, C.; Li, Y. Oat-Based Foods: Chemical Constituents, Glycemic Index, and the Effect of Processing. Foods 2021, 10, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmer, I.; Craddock, J.C.; Charlton, K.E. How do plant-based milks compare to cow’s milk nutritionally? An audit of the plant-based milk products available in Australia. Nutr. Diet. 2025, 82, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magwere, A.A.; Keast, R.; Gamlath, S.; Nandorfy, D.E.; Pematilleke, N.; Gambetta, J.M. A Comparative Study of the Sensory and Physicochemical Properties of Cow Milk and Plant-Based Milk Alternatives. J. Food Sci. 2025, 90, e70370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, N.W.; Dave, A.C.; Hill, J.P.; McNabb, W.C. Nutritional assessment of plant-based beverages in comparison to bovine milk. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 957486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vashisht, P.; Sharma, A.; Awasti, N.; Wason, S.; Singh, L.; Sharma, S.; Charles, A.P.R.; Sharma, S.; Gill, A.; Khattra, A.K. Comparative review of nutri-functional and sensorial properties, health benefits and environmental impact of dairy (bovine milk) and plant-based milk (soy, almond, and oat milk). Food Humanit. 2024, 2, 100301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walther, B.; Guggisberg, D.; Badertscher, R.; Egger, L.; Portmann, R.; Dubois, S.; Haldimann, M.; Kopf-Bolanz, K.; Rhyn, P.; Zoller, O.; et al. Comparison of nutritional composition between plant-based drinks and cow’s milk. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 988707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, I.C.; Roseiro, C.; Bexiga, R.; Pinto, C.; Lageiro, M.; Gonçalves, H.; Quaresma, M.A.G. Carbohydrate composition of cow milk and plant-based milk alternatives. J. Dairy Sci. 2025, 108, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starkey, D.E.; Wang, Z.; Brunt, K.; Dreyfuss, L.; Haselberger, P.A.; Holroyd, S.E.; Janakiraman, K.; Kasturi, P.; Konings, E.J.M.; Labbe, D.; et al. The Challenge of Measuring Sweet Taste in Food Ingredients and Products for Regulatory Compliance: A Scientific Opinion. J. AOAC Int. 2022, 105, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiwanon, P.; Puwastien, P.; Nitithamyong, A.; Sirichakwal, P.P. Calcium Fortification in Soybean Milk and In Vitro Bioavailability. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2000, 13, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pua, A.; Tang, V.C.Y.; Goh, R.M.V.; Sun, J.; Lassabliere, B.; Liu, S.Q. Ingredients, Processing, and Fermentation: Addressing the Organoleptic Boundaries of Plant-Based Dairy Analogues. Foods 2022, 11, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannucci, L.; Fossi, C.; Quattrini, S.; Guasti, L.; Pampaloni, B.; Gronchi, G.; Giusti, F.; Romagnoli, C.; Cianferotti, L.; Marcucci, G.; et al. Calcium Intake in Bone Health: A Focus on Calcium-Rich Mineral Waters. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melse-Boonstra, A. Bioavailability of Micronutrients From Nutrient-Dense Whole Foods: Zooming in on Dairy, Vegetables, and Fruits. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muleya, M.; Bailey, E.F.; Bailey, E.H. A comparison of the bioaccessible calcium supplies of various plant-based products relative to bovine milk. Food Res. Int. 2024, 175, 113795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoodi, S.H.; Shahbazi, R.; Esmaeili, S.; Sohrabvandi, S.; Mortazavian, A.; Jazayeri, S.; Taslimi, A. Health-Related Aspects of Milk Proteins. Iran J. Pharm. Res. 2016, 15, 573–591. [Google Scholar]

- Manary, M.J.; Wegner, D.R.; Maleta, K. Protein quality malnutrition. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1428810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathai, J.K.; Liu, Y.; Stein, H.H. Values for digestible indispensable amino acid scores (DIAAS) for some dairy and plant proteins may better describe protein quality than values calculated using the concept for protein digestibility-corrected amino acid scores (PDCAAS). Br. J. Nutr. 2017, 117, 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karoui, R.; Bouaicha, I. A review on nutritional quality of animal and plant-based milk alternatives: A focus on protein. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1378556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- N’Kouka, K.D.; Klein, B.P.; Lee, S.Y. Developing a Lexicon for Descriptive Analysis of Soymilks. J. Food Sci. 2004, 69, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawless, H.T.; Heymann, H. Preference Testing. In Sensory Evaluation of Food: Principles and Practices; Lawless, H.T., Heymann, H., Eds.; Springer New York: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 303–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, E., IV; Jenkins, A.; Mcguire, B.H. Flavor properties of plain soymilk. J. Sens. Stud. 2006, 21, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.L.; Kuo, W.Y.; Liou, B.K.; Chen, P.C.; Tseng, Y.C.; Huang, R.Y.; Tsai, M.C. Identifying sensory drivers of liking for plant-based milk coffees: Implications for product development and application. J. Food Sci. 2022, 87, 5418–5429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Zhong, F.; Chang, Y.; Li, Y. An Aromatic Lexicon Development for Soymilks. Int. J. Food Prop. 2015, 18, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossmann, L.; Kinchla, A.J.; Nolden, A.; McClements, D.J. Standardized methods for testing the quality attributes of plant-based foods: Milk and cream alternatives. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 2206–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawless, H.T.; Heymann, H. Sensory Evaluation of Food: Principles and Practices; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger, S.R.; Dupas de Matos, A.; Frempomaa Oduro, A.; Hort, J. Sensory characteristics of plant-based milk alternatives: Product characterisation by consumers and drivers of liking. Food Res. Int. 2024, 180, 114093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milovanovic, B.; Djekic, I.; Miocinovic, J.; Djordjevic, V.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Barba, F.J.; Mörlein, D.; Tomasevic, I. What Is the Color of Milk and Dairy Products and How Is It Measured? Foods 2020, 9, 1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daszkiewicz, T.; Florek, M.; Murawska, D.; Jabłońska, A. A comparison of the quality of UHT milk and its plant-based analogs. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107, 10299–10309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alozie, Y.; Yetunde, A.; Udofia, E. Nutritional and Sensory Properties of Almond (Prunus amygdalu Var. Dulcis) Seed Milk. World J. Dairy Food Sci. 2015, 10, 117–121. [Google Scholar]

- Kwok, K.C.; MacDougall, D.B.; Niranjan, K. Reaction kinetics of heat-induced colour changes in soymilk. J. Food Eng. 1999, 40, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobolková, B.; Durec, J. Colour descriptors for plant-based milk alternatives discrimination. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 60, 2497–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryamiharja, A.; Gong, X.; Zhou, H. Towards more sustainable, nutritious, and affordable plant-based milk alternatives: A critical review. Sustain. Food Proteins 2024, 2, 250–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, A.; Franks, G.V.; Hosken, R.W. Particle sizes and stability of UHT bovine, cereal and grain milks. Food Hydrocoll. 2003, 17, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, R.; Barker, S.; Falkeisen, A.; Gorman, M.; Knowles, S.; McSweeney, M.B. An investigation into consumer perception and attitudes towards plant-based alternatives to milk. Food Res. Int. 2022, 159, 111648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiebaud, M.; Dumay, E.; Picart, L.; Guiraud, J.P.; Cheftel, J.C. High-pressure homogenisation of raw bovine milk. Effects on fat globule size distribution and microbial inactivation. Int. Dairy J. 2003, 13, 427–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhlera, K.; Schuchmann, H.P. Homogenisation in the dairy process—Conventional processes and novel techniques. Procedia Food Sci. 2011, 1, 1367–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClements, D.J.; Newman, E.; McClements, I.F. Plant-based Milks: A Review of the Science Underpinning Their Design, Fabrication, and Performance. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2019, 18, 2047–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, D.; Lin, J.W.X.; Zhou, Y.; Yao, Y.; Chan, R.X.; Lê, K.A.; Kim, J.E. Enzymatic hydrolysis preserves nutritional properties of oat bran and improves sensory and physiochemical properties for powdered beverage application. LWT 2023, 181, 114729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClements, D.J. Development of Next-Generation Nutritionally Fortified Plant-Based Milk Substitutes: Structural Design Principles. Foods 2020, 9, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Lee, J.; Zhang, G.; Ebeler, S.E.; Wickramasinghe, N.; Seiber, J.; Mitchell, A.E. HS-SPME GC/MS characterization of volatiles in raw and dry-roasted almonds (Prunus dulcis). Food Chem. 2014, 151, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, L.M.; Mitchell, A.E. Review of the Sensory and Chemical Characteristics of Almond (Prunus dulcis) Flavor. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2019, 67, 2743–2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agila, A.; Barringer, S. Effect of Roasting Conditions on Color and Volatile Profile Including HMF Level in Sweet Almonds (Prunus dulcis). J. Food Sci. 2012, 77, C461–C468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vázquez-Araújo, L.; Verdú, A.; Navarro, P.; Martínez-Sánchez, F.; Carbonell-Barrachina, Á.A. Changes in volatile compounds and sensory quality during toasting of Spanish almonds. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2009, 44, 2225–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmenkallio-Marttila, M.; Heiniö, R.L.; Kaukovirta-Norja, A.; Poutanen, K. Flavor and Texture in Processing of New Oat Foods. In Oats, 2nd ed.; Webster, F.H., Wood, P.J., Eds.; AACC International Press: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2011; Chapter 16; pp. 333–346. Available online: https://www.cerealsgrains.org/publications/plexus/cfwplexus/Documents/2013/OatsChemCh16.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Huang, C.J.; Zayas, J.F. Phenolic Acid Contributions to Taste Characteristics of Corn Germ Protein Flour Products. J. Food Sci. 1991, 56, 1308–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molteberg, E.L.; Solheim, R.; Dimberg, L.H.; Frølich, W. Variation in Oat Groats Due to Variety, Storage and Heat Treatment. II: Sensory Quality. J. Cereal Sci. 1996, 24, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klensporf, D.; Jeleń, H.H. Effect of heat treatment on the flavor of oat flakes. J. Cereal Sci. 2008, 48, 656–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, X.; Huo, R. Effects of Pretreatment on the Volatile Composition, Amino Acid, and Fatty Acid Content of Oat Bran. Foods 2022, 11, 3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrdlčka, J.; Janíček, G. Carbonyl Compounds in Toasted Oat Flakes. Nature 1964, 201, 1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGorrin, R.J. Key Aroma Compounds in Oats and Oat Cereals. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2019, 67, 13778–13789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, N.; Bak, K.H.; Soladoye, O.P.; Aluko, R.E.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Insights into formation, detection and removal of the beany flavor in soybean protein. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 112, 336–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bott, L.; Chambers, E., IV. Sensory characteristics of combinations of chemicals potentially associated with beany aroma in foods. J. Sens. Stud. 2006, 21, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vara-Ubol, S.; Chambers, E.; Chambers, D.H. Sensory characteristics of chemical compounds potentially associated with beany aroma in foods. J. Sens. Stud. 2004, 19, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flavornet and Human Odor Space. Available online: https://www.flavornet.org/index.html (accessed on 24 November 2024).

- Duncan, S.E.; Webster, J.B. 4—Oxidation and protection of milk and dairy products. In Oxidation in Foods and Beverages and Antioxidant Applications; Decker, E.A., Elias, R.J., Julian McClements, D., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2010; pp. 121–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.P.; Barbano, D.M.; Drake, M.A. The influence of ultra-pasteurization by indirect heating versus direct steam injection on skim and 2% fat milks. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 1688–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Attabi, Z.; D’Arcy, B.R.; Deeth, H.C. Volatile sulfur compounds in pasteurised and UHT milk during storage. Dairy Sci. Technol. 2014, 94, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yi, S.; Lu, J.; Pang, X.; Xu, X.; Lv, J.; Zhang, S. Effect of different heat treatments on the Maillard reaction products, volatile compounds and glycation level of milk. Int. Dairy J. 2021, 123, 105182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkaya Öner, G. Use of Innovative Plant-Based Protein Sources in the Beverage Industry: Developments and Applications. Food Rev. Int. 2025, 41, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, B.V.; Brockhoff, P.B.; Hyldig, G. The importance of liking of appearance, -odour, -taste and -texture in the evaluation of overall liking. A comparison with the evaluation of sensory satisfaction. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 71, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolvachai, Y.; Amaral, M.S.S.; Herron, R.; Marriott, P.J. Solid phase microextraction for quantitative analysis – Expectations beyond design? Green Anal. Chem. 2023, 4, 100048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, M.C.; Peterson, D.G.; Reineccius, G.A. Gas Chromatography. In Food Analysis; Nielsen, S.S., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 227–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Ikram, S.; Zhao, T.; Shao, Y.; Liu, R.; Song, F.; Sun, B.; Ai, N. 2-Heptanone, 2-nonanone, and 2-undecanone confer oxidation off-flavor in cow milk storage. J. Dairy Sci. 2023, 106, 8538–8550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onuska, F.I.; Karasek, F.W. Quantitative Analysis. In Open Tubular Column Gas Chromatography in Environmental Sciences; Springer US: Boston, MA, USA, 1984; pp. 161–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGorrin, R.J. The Significance of Volatile Sulfur Compounds in Food Flavors. In Volatile Sulfur Compounds in Food; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; Volume 1068, pp. 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Zhogoleva, A.; Alas, M.; Rosenvald, S. Characterization of odor-active compounds of various pea preparations by GC-MS, GC-O, and their correlation with sensory attributes. Future Foods 2023, 8, 100243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Ningtyas, D.W.; Bhandari, B.; Liu, C.; Prakash, S. Oral perception of the textural and flavor characteristics of soy-cow blended emulsions. J. Texture Stud. 2022, 53, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.C.; Song, H.L.; Li, X.; Wu, L.; Guo, S.T. Influence of Blanching and Grinding Process with Hot Water on Beany and Non-Beany Flavor in Soymilk. J. Food Sci. 2011, 76, S20–S25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Yang, A.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, K.; Kuang, H.; Meng, F.; Wang, B. Identification of aroma-active compounds in milk by 2-dimensional gas chromatography-olfactometry-time-of-flight mass spectrometry combined with check-all-that-apply questions. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107, 9124–9134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarhoushang, B. 17—Process fluids for abrasive machining. In Tribology and Fundamentals of Abrasive Machining Processes, 3rd ed.; Azarhoushang, B., Marinescu, I.D., Brian Rowe, W., Dimitrov, B., Ohmori, H., Eds.; William Andrew Publishing: Norwich, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 615–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauss, M.S.; Linforth, R.S.; Cayeux, I.; Harvey, B.; Taylor, A.J. Altering the fat content affects flavor release in a model yogurt system. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1999, 47, 2055–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, E. Properties of Emulsions Stabilized with Milk Proteins: Overview of Some Recent Developments. J. Dairy Sci. 1997, 80, 2607–2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, C.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Fang, B.; Wang, R.; Wang, X.; Liao, H.; Li, G.; Wang, P.; et al. Structure, Biological Functions, Separation, Properties, and Potential Applications of Milk Fat Globule Membrane (MFGM): A Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.; Tu, S.; Ghosh, S.; Nickerson, M.T. Effect of pH on the inter-relationships between the physicochemical, interfacial and emulsifying properties for pea, soy, lentil and canola protein isolates. Food Res. Int. 2015, 77, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Roos, Y.H.; Miao, S. Structure, gelation mechanism of plant proteins versus dairy proteins and evolving modification strategies. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 147, 104464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, T.G.; Zhang, Y. Recent progress in the utilization of pea protein as an emulsifier for food applications. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 86, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Criado, D.; Jiménez-Rosado, M.; Perez-Puyana, V.; Romero, A. Soy Protein Isolate as Emulsifier of Nanoemulsified Beverages: Rheological and Physical Evaluation. Foods 2023, 12, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delahaije, R.J.B.M.; Gruppen, H.; Giuseppin, M.L.F.; Wierenga, P.A. Towards predicting the stability of protein-stabilized emulsions. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015, 219, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roesch, R.R.; Corredig, M. Characterization of Oil-in-Water Emulsions Prepared with Commercial Soy Protein Concentrate. J. Food Sci. 2002, 67, 2837–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damodaran, S.; Arora, A. Off-Flavor Precursors in Soy Protein Isolate and Novel Strategies for their Removal. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 4, 327–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhn, C.; Bufe, B.; Winnig, M.; Hofmann, T.; Frank, O.; Behrens, M.; Lewtschenko, T.; Slack, J.P.; Ward, C.D.; Meyerhof, W. Bitter taste receptors for saccharin and acesulfame K. J. Neurosci. 2004, 24, 10260–10265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silventoinen-Veijalainen, P.; Sneck, A.M.; Nordlund, E.; Rosa-Sibakov, N. Influence of oat flour characteristics on the physicochemical properties of oat-based milk substitutes. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 147, 109402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Food Additives and Flavourings (FAF); Younes, M.; Aquilina, G.; Castle, L.; Degen, G.; Engel, K.H.; Fowler, P.J.; Frutos Fernandez, M.J.; Fürst, P.; Gürtler, R.; et al. Re-evaluation of calcium carbonate (E 170) as a food additive in foods for infants below 16 weeks of age and follow-up of its re-evaluation as food additive for uses in foods for all population groups. EFSA J. 2023, 21, e08106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.R.A.; Silva, M.M.N.; Ribeiro, B.D. Health issues and technological aspects of plant-based alternative milk. Food Res. Int. 2020, 131, 108972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz Gonzalez, G.; Jimenez Flores, R.; Bremmer, D.R.; Clark, J.H.; DePeters, E.J.; Schmidt, S.J.; Drackley, J.K. Functional properties of cream from dairy cows with experimentally altered milk fat composition. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 3861–3870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, A.; Khatkar, B.S. Physicochemical, rheological and functional properties of fats and oils in relation to cookie quality: A review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 53, 3633–3641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajmal, M.; Nadeem, M.; Imran, M.; Junaid, M. Lipid compositional changes and oxidation status of ultra-high temperature treated Milk. Lipids Health Dis. 2018, 17, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, I.; Bexiga, R.; Pinto, C.; Gonçalves, H.; Roseiro, C.; Bessa, R.; Alves, S.; Quaresma, M. Lipid Profile of Plant-Based Milk Alternatives (PBMAs) and Cow’s Milk: A Comparison. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2024, 72, 18110–18120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, A.; Dong, Y.; Liu, Z.; Li, Z.; Shao, J.; Li, M.; Yue, X. A Review of Plant-Based Drinks Addressing Nutrients, Flavor, and Processing Technologies. Foods 2023, 12, 3952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klensporf, D.; Jeleń, H.H. Analysis of Volatile Aldehydes in Oat Flakes by SPME-GC/MS. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2005, 14/55, 389–395. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, S.H.; Chang, Y.H. Volatile Compound, Physicochemical, and Antioxidant Properties of Beany Flavor-Removed Soy Protein Isolate Hydrolyzates Obtained from Combined High Temperature Pre-Treatment and Enzymatic Hydrolysis. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 2016, 21, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poliseli-Scopel, F.H.; Hernández-Herrero, M.; Guamis, B.; Ferragut, V. Comparison of ultra high pressure homogenization and conventional thermal treatments on the microbiological, physical and chemical quality of soymilk. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silk Canada. Available online: https://www.silkcanada.ca/products/plant-based-beverage/nextmilk/ (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- CSIRO. Animal-Free Dairy. Available online: https://www.csiro.au/en/research/production/food/eden-brew (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Knychala, M.M.; Boing, L.A.; Ienczak, J.L.; Trichez, D.; Stambuk, B.U. Precision Fermentation as an Alternative to Animal Protein, a Review. Fermentation 2024, 10, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisner, M.D. Milk without animals—A dairy science perspective. Int. Dairy J. 2024, 156, 105978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Han, C.; Feng, G.; Guo, J.; Wan, Z.; Yang, X. Enhanced creaminess of plant-based milk via enrichment of papain hydrolyzed oleosomes. Food Res. Int. 2024, 198, 115322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapp, L.; Schacht, H.; Nirschl, H.; Guthausen, G. Oleosomes in almonds and hazelnuts: Structural investigations by NMR. Front. Phys. 2025, 13, 1494052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson-Harman, N.J.; Stevens, R.; Walker, S.; Gamble, J.; Miller, M.; Wong, M.; McPherson, A. Mapping consumer perceptions of creaminess and liking for liquid dairy products. Food Qual. Prefer. 2000, 11, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Li, Z.; Cao, X.; Duan, J.; Shi, X.; Wu, C.; Cui, B.; Zhou, B. Improvement of physicochemical properties and stabilization of oat milk by composite enzymatic hydrolysis. Food Res. Int. 2025, 219, 117146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tangyu, M.; Fritz, M.; Tan, J.P.; Ye, L.; Bolten, C.J.; Bogicevic, B.; Wittmann, C. Flavour by design: Food-grade lactic acid bacteria improve the volatile aroma spectrum of oat milk, sunflower seed milk, pea milk, and faba milk towards improved flavour and sensory perception. Microb. Cell Factories 2023, 22, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagden, T.D.; Gilliland, S.E. Reduction of Levels of Volatile Components Associated with the “Beany” Flavor in Soymilk by Lactobacilli and Streptococci. J. Food Sci. 2005, 70, M186–M189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekha, C.R.; Vijayalakshmi, G. Bioconversion of isoflavone glycosides to aglycones, mineral bioavailability and vitamin B complex in fermented soymilk by probiotic bacteria and yeast. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 109, 1198–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora, A.; Guamis, B. Opportunities for Ultra-High-Pressure Homogenisation (UHPH) for the Food Industry. Food Eng. Rev. 2015, 7, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vela, A.J.; Villanueva, M.; Solaesa, Á.G.; Ronda, F. Impact of high-intensity ultrasound waves on structural, functional, thermal and rheological properties of rice flour and its biopolymers structural features. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 113, 106480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarangapany, A.K.; Murugesan, A.; Annamalai, A.S.; Balasubramanian, A.; Shanmugam, A. An overview on ultrasonically treated plant-based milk and its properties—A Review. Appl. Food Res. 2022, 2, 100130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, N.; Capellas, M.; Hernández, M.; Trujillo, A.J.; Guamis, B.; Ferragut, V. Ultra high pressure homogenization of soymilk: Microbiological, physicochemical and microstructural characteristics. Food Res. Int. 2007, 40, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NotCo. Giuseppe AI. Available online: https://tech.notco.com/giuseppeai (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- Lee, P.Y.; Leong, S.Y.; Oey, I. The role of protein blends in plant-based milk alternative: A review through the consumer lens. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 143, 104268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Almond | Oat | Soy | UHT Cow milk | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macronutrients (g/100 g) | |||||

| Carbohydrates including sugars | 1.7–2.8 | 6.1–6.7 | 4.8–5.5 | 4.8–5.0 | [40,41] |

| Total sugars | 1.3–1.7 | 1.8–2.7 | 1.8–2.2 | 4.8–5.0 | [40,41] |

| Dietary Fibre | 0.3–0.4 | 0.9–1.3 | 0.4–0.8 | 0.0 | [32,42,43] |

| Proteins | 0.6–0.7 | 1.1–1.2 | 3.2–3.6 | 3.2–3.4 | [32,40,44] |

| Fat | 1.8–2.5 | 2.0–3.0 | 2.2–3.0 | 3.4–3.5 | [40,41,44] |

| Micronutrients (mg/100 g) | |||||

| Calcium | 65.6 | 49.9 | 84.2 | 112 | [44] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Magwere, A.A.; Logan, A.; Gamlath, S.; Gambetta, J.M.; Kukuljan, S.; Keast, R. Can Plant-Based Milk Alternatives Fully Replicate UHT Cow Milk? A Review of Sensory and Physicochemical Attributes. Beverages 2025, 11, 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11060171

Magwere AA, Logan A, Gamlath S, Gambetta JM, Kukuljan S, Keast R. Can Plant-Based Milk Alternatives Fully Replicate UHT Cow Milk? A Review of Sensory and Physicochemical Attributes. Beverages. 2025; 11(6):171. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11060171

Chicago/Turabian StyleMagwere, Anesu A., Amy Logan, Shirani Gamlath, Joanna M. Gambetta, Sonja Kukuljan, and Russell Keast. 2025. "Can Plant-Based Milk Alternatives Fully Replicate UHT Cow Milk? A Review of Sensory and Physicochemical Attributes" Beverages 11, no. 6: 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11060171

APA StyleMagwere, A. A., Logan, A., Gamlath, S., Gambetta, J. M., Kukuljan, S., & Keast, R. (2025). Can Plant-Based Milk Alternatives Fully Replicate UHT Cow Milk? A Review of Sensory and Physicochemical Attributes. Beverages, 11(6), 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11060171