Analytical and Chemometric Evaluation of Yerba Mate (Ilex paraguariensis A.St.-Hil.) in Terms of Mineral Composition

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples

2.2. Preparation of Samples

2.3. Elemental Analysis

2.4. Method Validation

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Macroelements

3.2. Microelements

| Na [mg/100 g] | K [mg/100 g] | Ca [mg/100 g] | Mg [mg/100 g] | P [mg/100 g] | Co [mg/100 g] | Cd [mg/100 g] | Cr [mg/100 g] | Cu [mg/100 g] | Fe [mg/100 g] | Mn [mg/100 g] | Zn [mg/100 g] | Ni [mg/100 g] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina 11x3 | 1.49 ± 0.43 (0.95–2.22) 75.3 ± 38.8% | 1197 ± 199 (569–1516) 31.5 ± 13.9% | 767 ± 67.4 (667–912) 22.5 ± 4.59% | 448 ± 69.3 (319–554) 12.3 ± 6.04% | 158 ± 3.61 (73.7–198) 13.1 ± 2.38% | 0.04 ± 0.01 (0.03–0.06) 9.71 ± 1.65% | 0.03 ± 0.01 (0.02–0.05) 22.4 ± 4.80% | 0.08 ± 0.01 (0.07–0.09) 6.64 ± 1.04% | 0.80 ± 0.05 (0.73–0.92) 8.93 ± 1.15% | 19.4 ± 3.60 (13.6–25.0) 3.94 ± 0.94% | 153 ± 23.5 (112–197) 6.58 ± 1.03% | 8.67 ± 2.03 (5.25–11.2) 6.88 ± 1.30% | 0.46 ± 0.12 (0.32–0.80) 16.2 ± 4.96% |

| Brazil 4 × 3 | 2.92 ± 0.74 (1.69–3.62) 23.6 ± 14.1% | 1475 ± 239 (1175–1702) 12.9 ± 2.32% | 719 ± 45.8 (663–788) 29.0 ± 3.71% | 493 ± 84.5 (403–627) 12.0 ± 2.03% | 111 ± 2.82 (64–166) 12.5 ± 4.84% | 0.02 ± 0.01 (0.02–0.02) < LOD | 0.05 ± 0.01 (0.04–0.06) 16.1 ± 1.50% | 0.08 ± 0.03 (0.04–0.13) 5.18 ± 1.20% | 0.98 ± 0.11 (0.79–1.07) 9.80 ± 1.62% | 15.5 ± 1.84 (12.6–17.1) 5.44 ± 0.82% | 141 ± 26.4 (106–178) 6.73 ± 0.96% | 7.60 ± 0.82 (6.28–8.35) 6.64 ± 0.58% | 0.19 ± 0.04 (0.15–0.26) 21.3 ± 4.23% |

| Paraguay 10 × 3 | 1.76 ± 1.25 (0.59–5.11) 52.9 ± 43.6% | 1381 ± 171 (1228–1452) 16.6 ± 1.65% | 793 ± 29.7 (750–854) 21.3 ± 5.84% | 441 ± 34.0 (386–508) 15.3 ± 3.94% | 133 ± 5.93 (36.2–188) 15.1 ± 5.47% | 0.03 ± 0.01 (0.01–0.05) 10.6 ± 1.47% | 0.05 ± 0.01 (0.03–0.07) 20.3 ± 3.53% | 0.09 ± 0.05 (0.04–0.21) 8.96 ± 6.55% | 0.82 ± 0.06 (0.71–0.93) 10.2 ± 0.99% | 24.0 ± 10.3 (14.5–51.9) 5.61 ± 2.46% | 100 ± 16.8 (66.5–132) 7.94 ± 1.44% | 11.0 ± 2.21 (5.99–13.3) 6.45 ± 0.86% | 0.40 ± 0.15 (0.25–0.80) 19.7 ± 6.55% |

| Uruguay 5 × 3 | 3.01 ± 0.32 (2.72–3.58) 49.0 ± 34.2% | 1349 ± 92.3 (1247–1429) 16.3 ± 1.67% | 814 ± 45.3 (729–851) 29.0 ± 6.14% | 603 ± 11.2 (522–824) 14.2 ± 3.39% | 182 ± 1.75 (111–222) 11.6 ± 1.53% | 0.03 ± 0.01 (0.02–0.04) 14.9 ± 1.56% | 0.04 ± 0.01 (0.03–0.05) 24.8 ± 7.72% | 0.06 ± 0.01 (0.05–0.08) 7.49 ± 1.97% | 1.01 ± 0.05 (0.93–1.09) 11.5 ± 1.91% | 21.4 ± 4.39 (16.1–27.6) 5.51 ± 1.05% | 146 ± 6.98 (136–155) 7.57 ± 0.55% | 7.63 ± 0.94 (6.54–9.26) 8.17 ± 2.00% | 0.31 ± 0.06 (0.27–0.42) 17.6 ± 5.18% |

3.3. Toxic Elements

3.4. Kruskal–Wallis Test

3.5. Dunn’s Test

3.6. Correlation Analysis

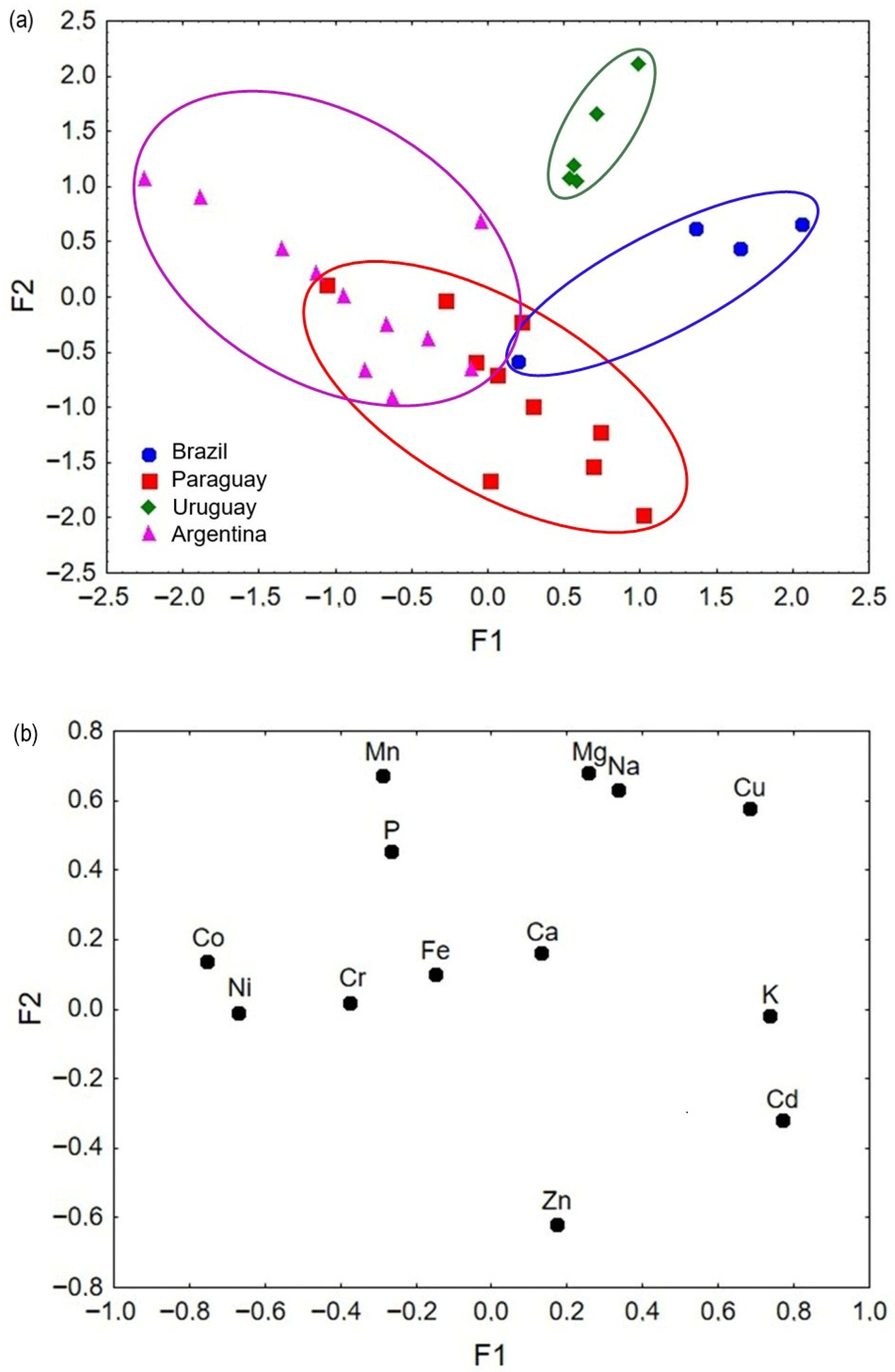

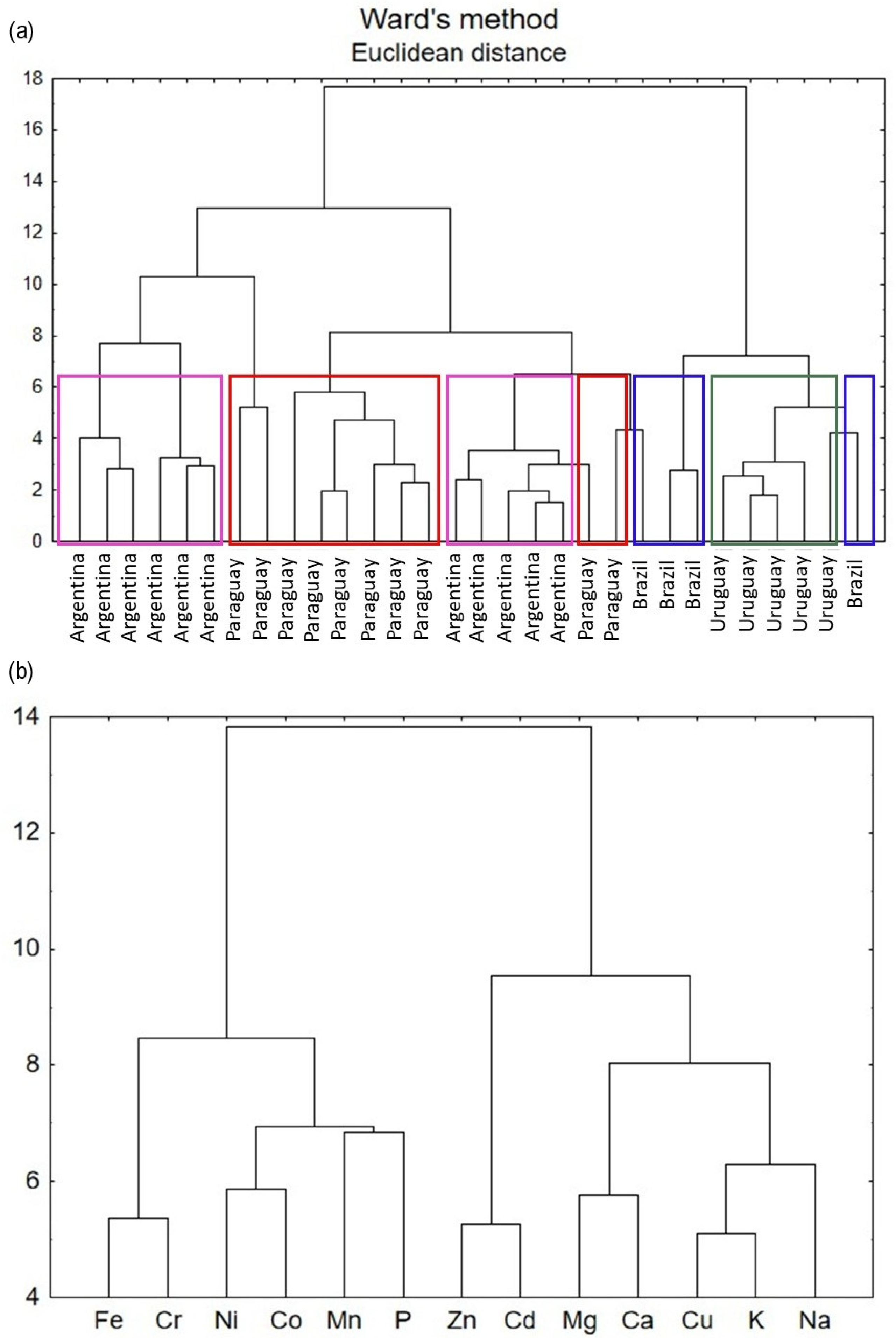

3.7. Factor Analysis

3.8. Cluster Analysis

3.9. Assessment of Mineral Compounds Intake and Safety of Yerba Mate Infusions

3.9.1. Recommended Dietary Intake of Elements

3.9.2. Assessment of Exposure to Toxic Metals

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANIVISA | Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency |

| FAAS | Flame Atomic Absorption Spectrometry |

| LOD | Limit Of Detection |

| LOQ | Limit Of Quantification |

| RDA | Recommended Dietary Allowances |

| AI | Adequate Intake |

| PTMI | Provisional Tolerable Monthly Intake |

| FA | Factor Analysis |

| CA | Cluster Analysis |

| FAO/WHO | United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the World Health Organization (WHO) |

Appendix A

| Element | Wavelength (nm) | Slot (nm) | Fuel Flow (L/min) | Burner Height (mm) | Background Correction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na | 589 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 6.8 | − |

| K | 766.5 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 7 | − |

| Ca | 422.7 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 6.8 | − |

| Mg | 285.2 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 6.5 | − |

| Co | 240.7 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 9 | + |

| Cd | 228.8 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 7.5 | + |

| Cr | 357.9 | 0.5 | 1.1 | 9.2 | + |

| Cu | 324.8 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 7.3 | + |

| Fe | 248.3 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 8 | + |

| Mn | 279.5 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 7 | + |

| Zn | 213.9 | 0.2 | 1.2 | 7 | + |

| Ni | 232 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 7 | + |

| Pb | 217 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 5.3 | + |

References

- Heck, C.I.; De Mejia, E.G. Yerba Mate Tea (Ilex paraguariensis): A Comprehensive Review on Chemistry, Health Implications, and Technological Considerations. J. Food Sci. 2007, 72, R138–R151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bracesco, N.; Sanchez, A.G.; Contreras, V.; Menini, T.; Gugliucci, A. Recent Advances on Ilex paraguariensis Research: Minireview. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 136, 378–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkhatib, A.; Atcheson, R. Yerba Maté (Ilex paraguariensis) Metabolic, Satiety, and Mood State Effects at Rest and during Prolonged Exercise. Nutrients 2017, 9, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dmowski, P.; Post, L. Influence of the Multiplicity Yerba Mate Brewing on the Antioxidant Activity of the Beverages. Sci. J. Gdyn. Marit. Univ. 2018, 104, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawron-Gzella, A.; Chanaj-Kaczmarek, J.; Cielecka-Piontek, J. Yerba Mate—A Long but Current History. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutomski, P.; Goździewska, M.; Florek-Łuszczki, M. Health Properties of Yerba Mate. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2020, 27, 310–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maximize Market Research. Available online: https://www.maximizemarketresearch.com/market-report/global-yerba-mate-market/23486 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Pawan, G. Yerba Mate Market Size, Share, Trends, Analysis, Growth, & Forecast by 2029; Data Bridge Market Research Private Ltd.: Pune, India, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Olivari, I.; Paz, S.; Gutiérrez, Á.J.; González-Weller, D.; Hardisson, A.; Sagratini, G.; Rubio, C. Macroelement, Trace Element, and Toxic Metal Levels in Leaves and Infusions of Yerba Mate (Ilex paraguariensis). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 21341–21352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcelo, M.C.A.; Martins, C.A.; Pozebon, D.; Dressler, V.L.; Ferrão, M.F. Classification of Yerba Mate (Ilex paraguariensis) According to the Country of Origin Based on Element Concentrations. Microchem. J. 2014, 117, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toppel, F.V.; Junior, A.M.; Motta, A.C.V.; Frigo, C.; Magri, E.; Barbosa, J.Z. Soil Chemical Attributes and Their Influence on Elemental Composition of Yerba Mate Leaves. Floresta 2018, 48, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magri, E.; Valduga, A.T.; Gonçalves, I.L.; Barbosa, J.Z.; Rabel, D.D.O.; Menezes, I.M.N.R.; Nascimento, P.D.A.; Oliveira, A.; Corrêa, R.S.; Motta, A.C.V. Cadmium and Lead Concentrations in Yerba Mate Leaves from Agroforestry and Plantation Systems: An International Survey in South America. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2021, 96, 103702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camotti Bastos, M.; Cherobim, V.F.; Reissmann, C.B.; Fernandes Kaseker, J.; Gaiad, S. Yerba Mate: Nutrient Levels and Quality of the Beverage Depending on the Harvest Season. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2018, 69, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibourki, M.; Hallouch, O.; Devkota, K.; Guillaume, D.; Hirich, A.; Gharby, S. Elemental Analysis in Food: An Overview. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 120, 105330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulbrich, N.C.M.; Do Prado, L.L.; Barbosa, J.Z.; Araujo, E.M.; Poggere, G.; Motta, A.C.V.; Prior, S.A.; Magri, E.; Young, S.D.; Broadley, M.R. Multi-Elemental Analysis and Health Risk Assessment of Commercial Yerba Mate from Brazil. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2022, 200, 1455–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berté, K.; Rodriguez–Amaya, D.B.; Hoffmann-Ribani, R.; Junior, A.M. Antioxidant Activity of Maté Tea and Effects of Processing. In Processing and Impact on Antioxidants in Beverages; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 145–153. ISBN 978-0-12-404738-9. [Google Scholar]

- De Morais, E.C.; Stefanuto, A.; Klein, G.A.; Boaventura, B.C.B.; De Andrade, F.; Wazlawik, E.; Di Pietro, P.F.; Maraschin, M.; Da Silva, E.L. Consumption of Yerba Mate (Ilex paraguariensis) Improves Serum Lipid Parameters in Healthy Dyslipidemic Subjects and Provides an Additional LDL-Cholesterol Reduction in Individuals on Statin Therapy. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 8316–8324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arçari, D.P.; Bartchewsky, W.; dos Santos, T.W.; Oliveira, K.A.; DeOliveira, C.C.; Gotardo, É.M.; Pedrazzoli, J.; Gambero, A.; Ferraz, L.F.C.; Carvalho, P.d.O.; et al. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Yerba Maté Extract (Ilex paraguariensis) Ameliorate Insulin Resistance in Mice with High Fat Diet-Induced Obesity. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2011, 335, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.-Y.; Oh, M.-R.; Kim, M.-G.; Chae, H.-J.; Chae, S.-W. Anti-Obesity Effects of Yerba Mate (Ilex paraguariensis): A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 15, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomova, K.; Makova, M.; Alomar, S.Y.; Alwasel, S.H.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Rhodes, C.J.; Valko, M. Essential Metals in Health and Disease. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2022, 367, 110173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschner, J.L.; Aschner, M. Nutritional Aspects of Manganese Homeostasis. Mol. Aspects Med. 2005, 26, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fijorek, K.; Püsküllüoğlu, M.; Tomaszewska, D.; Tomaszewski, R.; Glinka, A.; Polak, S. Serum Potassium, Sodium and Calcium Levels in Healthy Individuals—Literature Review and Data Analysis. Folia Med. Cracov. 2014, 54, 53–70. [Google Scholar]

- Rychlik, E.; Stoś, K.; Woźniak, A.; Mojska, H. Normy Żywienia dla Populacji Polski; Narodowy Instytut Zdrowia Publicznego PZH—Państwowy Instytut Badawczy: Warszawa, Poland, 2024; ISBN 978-83-65870-78-0.

- Wołonciej, M.; Milewska, E.; Roszkowska-Jakimiec, W. Trace Elements as an Activator of Antioxidant Enzymes. Postęp. Hig. Med. Dośw. 2016, 70, 1483–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippini, T.; Violi, F.; D’Amico, R.; Vinceti, M. The Effect of Potassium Supplementation on Blood Pressure in Hypertensive Subjects: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017, 230, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietary Reference Values for Iron | EFSA. Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/efsajournal/pub/4254 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Harrison, R.M.; Chirgawi, M.B. The Assessment of Air and Soil as Contributors of Some Trace Metals to Vegetable Plants I. Use of a Filtered Air Growth Cabinet. Sci. Total Environ. 1989, 83, 13–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministro de Estado da Saúde. Available online: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/anvisa/2013/rdc0042_29_08_2013.html (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Ośko, J.; Szewczyk, A.; Berk, P.; Prokopowicz, M.; Grembecka, M. Assessment of the Mineral Composition and the Selected Physicochemical Parameters of Dietary Supplements Containing Green Tea Extracts. Foods 2022, 11, 3580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodionova, O.Y.; Oliveri, P.; Malegori, C.; Pomerantsev, A.L. Chemometrics as an Efficient Tool for Food Authentication: Golden Pillars for Building Reliable Models. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 147, 104429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczuk, N.; Krauze-Baranowska, M.; Ośko, J.; Grembecka, M.; Migas, P. Comparison of Antioxidant Properties of Fruit from Some Cultivated Varieties and Hybrids of Rubus Idaeus and Rubus occidentalis. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, W.F.D.C.; Prado, C.B.D.; Blonder, N. Comparison of Chemometric Problems in Food Analysis Using Non-Linear Methods. Molecules 2020, 25, 3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinholds, I.; Bartkevics, V.; Silvis, I.C.J.; Van Ruth, S.M.; Esslinger, S. Analytical Techniques Combined with Chemometrics for Authentication and Determination of Contaminants in Condiments: A Review. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2015, 44, 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International. Official Method 991.25. Calcium, Magnesium, and Phosphorus in Cheese—Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometric and Colorimetric Method, 17th ed.; AOAC International: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Konieczka, P.; Namieśnik, J. Quality Assurance and Quality Control in the Analytical Chemical Laboratory: A Practical Approach; CRC Press–Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pozebon, D.; Dressler, V.L.; Marcelo, M.C.A.; De Oliveira, T.C.; Ferrão, M.F. Toxic and Nutrient Elements in Yerba Mate (Ilex paraguariensis). Food Addit. Contam. Part B 2015, 8, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, J.; Szakova, J.; Drabek, O.; Balik, J.; Kokoska, L. Determination of Certain Micro and Macroelements in Plant Stimulants and Their Infusions. Food Chem. 2008, 111, 520–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proch, J.; Różewska, A.; Orłowska, A.; Niedzielski, P. Influence of Brewing Method on the Content of Selected Elements in Yerba Mate (Ilex paraguarensis) Infusions. Foods 2023, 12, 1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Różewska, A.; Proch, J.; Niedzielski, P. Leaves, Infusion, and Grounds—A Three–Stage Assessment of Element Content in Yerba Mate (Ilex paraguariensis) Based on the Dynamic Extraction and Mineralization of Residues. Foods 2024, 13, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proch, J.; Orłowska, A.; Niedzielski, P. Elemental and Speciation Analyses of Different Brands of Yerba Mate (Ilex paraguariensis). Foods 2021, 10, 2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa, J.Z.; Zambon, L.M.; Motta, A.C.V.; Wendling, I. Composition, Hot-Water Solubility of Elements and Nutritional Value of Fruits and Leaves of Yerba Mate. Ciênc. Agrotecnol. 2015, 39, 593–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, R.F.; Silvestre, L.K.; Morgano, M.A.; Cadore, S. Investigation of Twelve Trace Elements in Herbal Tea Commercialized in Brazil. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2019, 52, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, J.Z.; Motta, A.C.V.; Consalter, R.; Poggere, G.C.; Santin, D.; Wendling, I. Plant Growth, Nutrients and Potentially Toxic Elements in Leaves of Yerba Mate Clones in Response to Phosphorus in Acid Soils. An. Acad. Bras. Ciênc. 2018, 90, 557–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabata-Pendias, A.; Szteke, B. Trace Elements in Abiotic and Biotic Environments, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-0-429-16151-3. [Google Scholar]

- Ceconi, D.E.; Poletto, I.; Lovato, T.; Muniz, M.F.B. Exigência Nutricional de Mudas de Erva-Mate (Ilex paraguariensis A. St.-Hil.) à Adubação Fosfatada. Ciênc. Florest. 2007, 17, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santin, D.; Benedetti, E.L.; Bastos, M.C.; Kaseker, J.F.; Reissmann, C.B.; Brondani, G.E.; Barros, N.F.D. Crescimento e Nutrição de Erva-Mate Influenciados Pela Adubação Nitrogenada, Fosfatada e Potássica. Ciênc. Florest. 2013, 23, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, J.J.; Burden, T.J.; Thompson, R.P.H. In Vitro Mineral Availability from Digested Tea: A Rich Dietary Source of Manganese. Analyst 1998, 123, 1721–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulshreshtha, D.; Ganguly, J.; Jog, M. Manganese and Movement Disorders: A Review. J. Mov. Disord. 2021, 14, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evaluation of Certain Food Additives and Contaminants: Seventy-Third Report of the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241209601 (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Filip, K.; Grynkiewicz, G.; Gruza, M.; Jatczak, K.; Zagrodzki, B. Comparison of Ultraviolet Detection and Charged Aerosol Detection Methods for Liquid-Chromatographic Determination of Protoescigenin. Acta Pol. Pharm. 2014, 71, 933–940. [Google Scholar]

| No. | Product | Country of Origin |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Verde Mate Green Despalada | Brazil |

| 2 | Yaguar Elaborada | Brazil |

| 3 | Barao De Cotegipe Nativa | Brazil |

| 4 | Barao De Cotegipe Premium | Brazil |

| 5 | La Rubia | Paraguay |

| 6 | Colon Traditional | Paraguay |

| 7 | La Bombila | Paraguay |

| 8 | Pajarito Suave | Paraguay |

| 9 | Pajarito Premium Despalada | Paraguay |

| 10 | Pajarito Elaborada Con Palo Tradicional | Paraguay |

| 11 | Indega Selection Especial | Paraguay |

| 12 | Selecta Elaborada Con Palo | Paraguay |

| 13 | Kurupi Traditional | Paraguay |

| 14 | Campesino Clasica | Paraguay |

| 15 | Contigo | Uruguay |

| 16 | Yerba mate elaborada Canarias | Uruguay |

| 17 | Armino Suave | Uruguay |

| 18 | Sara Roja Traditional | Uruguay |

| 19 | La Selva es cosa buena traditional | Uruguay |

| 20 | Union Suave | Argentina |

| 21 | Rosamate Sabor Suave | Argentina |

| 22 | Taragui | Argentina |

| 23 | Pipore elaborada con Palo | Argentina |

| 24 | Cruz de Malta | Argentina |

| 25 | Yerba mate Andresito Elaborada Tradicional | Argentina |

| 26 | Yerba mate Aguantadora Elaborada Tradicional | Argentina |

| 27 | Sinceridad Sauve | Argentina |

| 28 | Rosamonte | Argentina |

| 29 | Yerba mate Amanda Elaborada Tradicional | Argentina |

| 30 | Yerba mate Amanda Despalada | Argentina |

| Element | Certified Values [mg/100 g] | Determined Values [mg/100 g] | Recovery [%] | RSD [%] | LOD [mg/100 g] | LOQ [mg/100 g] | Linearity | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | 3859 ± 142 | 3566 ± 149 | 92 | 4.17 | 0.012 | 0.036 | y = 0.00004x − 0.0005 | 0.9999 |

| Co | 0.10 ± 0.007 | 0.09 ± 0.005 | 90 | 5.65 | 0.014 | 0.042 | y = 0.00006x + 0.0041 | 0.9989 |

| Cu | 1.01 ± 0.04 | 1.00 ± 0.01 | 99 | 1.42 | 0.003 | 0.009 | y = 0.0001x + 0.0006 | 0.9998 |

| Cd | 0.26 ± 0.01 | 0.28 ± 0.01 | 105 | 3.48 | 0.002 | 0.006 | y = 0.0003x + 0.0083 | 0.9996 |

| Cr | 0.63 * | 0.56 ± 0.0001 | 89 | 0.02 | 0.001 | 0.003 | y = 0.00004x + 0.0009 | 0.9997 |

| Mg | 853 ± 34 | 845 ± 4.96 | 99 | 0.59 | 0.001 | 0.003 | y = 0.001x + 0.0186 | 0.9998 |

| Mn | 18.0 ± 0.6 | 20.2 ± 0.34 | 112 | 1.67 | 0.002 | 0.006 | y = 0.0001x + 0.0019 | 0.9996 |

| Zn | 5.24 ± 0.18 | 5.59 ± 0.24 | 107 | 4.31 | 0.012 | 0.036 | y = 0.00003x + 0.0033 | 0.9988 |

| K | 2271 ± 76 | 2449 ± 50.3 | 108 | 2.06 | 0.001 | 0.003 | y = 0.0003x + 0.0016 | 0.9997 |

| Na | 90 ± 10 | 88.0 ± 9.00 | 98 | 10.2 | 0.007 | 0.021 | y = 0.0006x − 0.0011 | 0.9999 |

| Pb | 0.20 ± 0.03 | 0.19 ± 0.01 | 95 | 5.60 | 0.020 | 0.060 | y = 0.00003x − 0.00005 | 0.9996 |

| P | 170 ± 2 | 170 ± 0.41 | 100 | 0.24 | 2.698 | 8.094 | y = 0.0036x + 0.0053 | 0.9993 |

| Ni | 0.85 ± 0.05 | 0.80 ± 0.08 | 94 | 9.80 | 0.086 | 0.258 | y = 0.00006x + 0.0002 | 0.9999 |

| Fe | 149 * | 160 ± 1.01 | 107 | 0.63 | 0.008 | 0.024 | y = 0.00005x + 0.0029 | 0.9988 |

| Brazil | Paraguay | Uruguay | Argentina | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brazil | - | Pa | Co a,b, Ni a,b,c | |

| Paraguay | - | Mg a, Cu a, Mn a | Mn a,b,c | |

| Uruguay | P a | Mg a, Cu a, Mn a | - | Mg a Cu a,b, Na a |

| Argentina | Co a,b, Ni a,b,c | Mn a,b,c | Mg a, Cu a,b, Na a | - |

| Element | Recommended Daily Allowance/Adequate Intake (RDA/AI) [mg/day/person] | Average Content (mg/200 mL) | Realisation of RDA Through Consumption of 200 mL of Infusion [%] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males (31–50 Years) | Females (31–50 Years) | Males (31–50 Years) | Females (31–50 Years) | ||

| Ca | 1000 | 1000 | 18.6 ± 4.67 (9.69–29.4) | 1.86 | 1.86 |

| K * | 3500 | 3500 | 193 ± 26.7 (139–234) | 5.54 | 5.54 |

| Mg | 420 | 320 | 60.5 ± 14.0 (41.6–85.1) | 14.4 | 18.9 |

| Na * | 1500 | 1500 | 0.86 ± 0.69 (<LOD-2.61) | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| P | 700 | 700 | 12.3 ± 2.77 (6.26–16.0) | 1.75 | 1.75 |

| Mn * | 2.3 | 1.8 | 8.57 ± 2.16 (4.89–13.1) | 372 | 476 |

| Fe | 10 | 18 | 0.09 ± 0.03 (0.04–0.15) | 0.87 | 0.48 |

| Zn | 11 | 8 | 0.56 ± 0.13 (0.32–0.81) | 5.06 | 6.96 |

| Cu | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.09 ± 0.02 (0.05–0.13) | 9.52 | 9.52 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ośko, J.; Bojarowska, A.; Orłowska, W.; Grembecka, M. Analytical and Chemometric Evaluation of Yerba Mate (Ilex paraguariensis A.St.-Hil.) in Terms of Mineral Composition. Beverages 2025, 11, 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11060172

Ośko J, Bojarowska A, Orłowska W, Grembecka M. Analytical and Chemometric Evaluation of Yerba Mate (Ilex paraguariensis A.St.-Hil.) in Terms of Mineral Composition. Beverages. 2025; 11(6):172. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11060172

Chicago/Turabian StyleOśko, Justyna, Aleksandra Bojarowska, Wiktoria Orłowska, and Małgorzata Grembecka. 2025. "Analytical and Chemometric Evaluation of Yerba Mate (Ilex paraguariensis A.St.-Hil.) in Terms of Mineral Composition" Beverages 11, no. 6: 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11060172

APA StyleOśko, J., Bojarowska, A., Orłowska, W., & Grembecka, M. (2025). Analytical and Chemometric Evaluation of Yerba Mate (Ilex paraguariensis A.St.-Hil.) in Terms of Mineral Composition. Beverages, 11(6), 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11060172