Preparation of “Ginger-Enriched Wine” and Study of Its Physicochemical and Organoleptic Stability

Highlights

- Roditis Alepou and Muscat of Patras grapes were vinified.

- Ginger was added at different concentrations post-fermentation and in different forms.

- Ginger-enriched wine showed good physicochemical and organoleptic stability.

- New perspectives were provided for dry white wine aromatized with ginger or ginger extract.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples

2.2. Preparation of Wine Samples

2.2.1. Preparation of Ginger Extracts in Ethanol

2.2.2. Filtration of the Ethanol Extract

2.2.3. Ginger Powder Extraction in Grape Must

2.2.4. Filtration of Ginger Must

2.2.5. Ginger Powder Extraction in Wine

2.2.6. Filtration of Ginger-Enriched Wine

2.2.7. Wine Distillation

2.2.8. Ginger Powder Extraction in Viticultural Ethanol

2.2.9. Filtration and Application of Ginger Extracts

2.3. Preparation of DPPH∙ Standard Solution

Determination of In Vitro Antioxidant Activity

2.4. Determination of Total Acidity and Effective Acidity (pH)

2.5. Determination of Color Parameters

2.6. Determination of Total Phenolic Content

2.7. Sensory Analysis

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Physicochemical Parameters

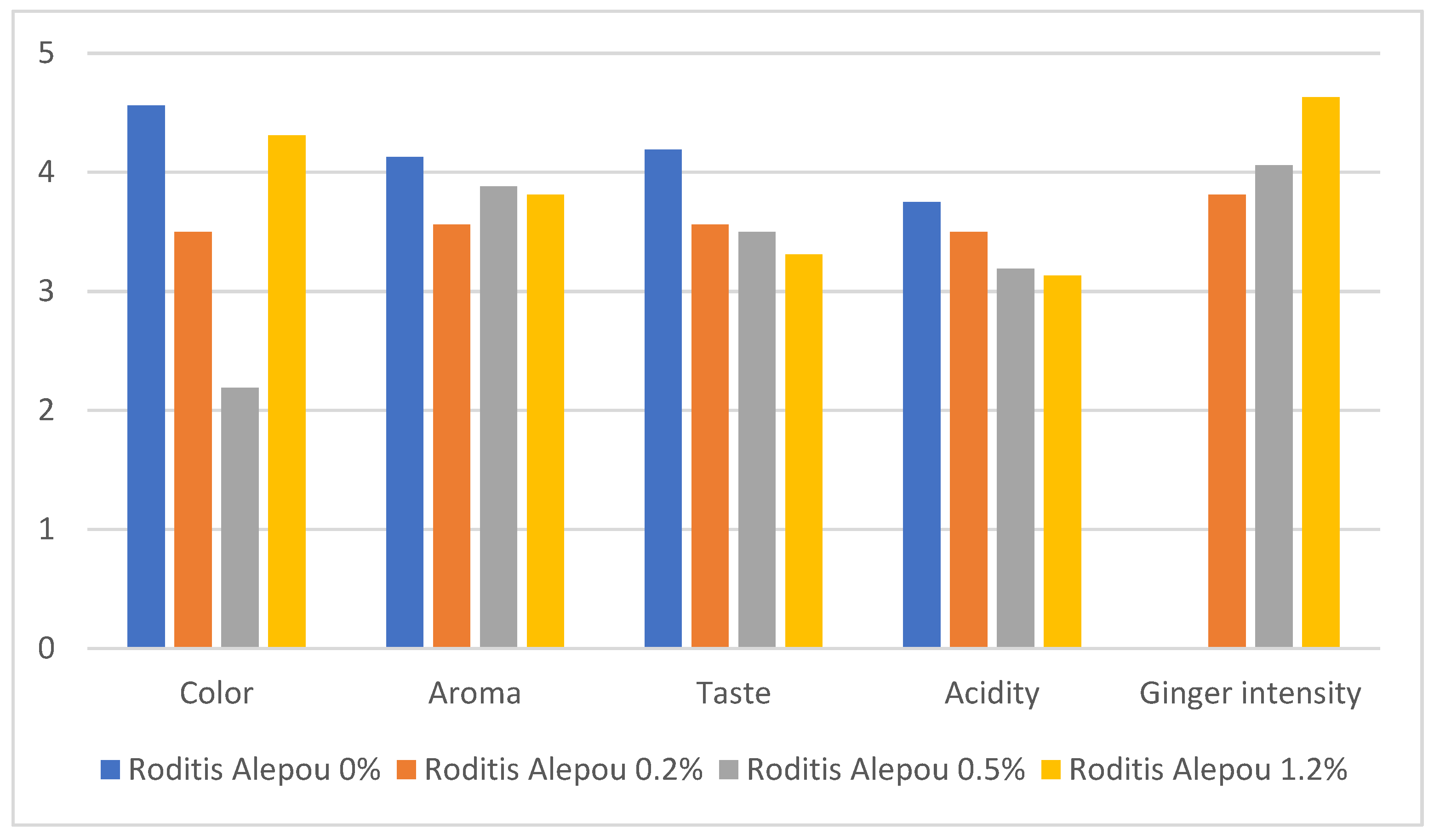

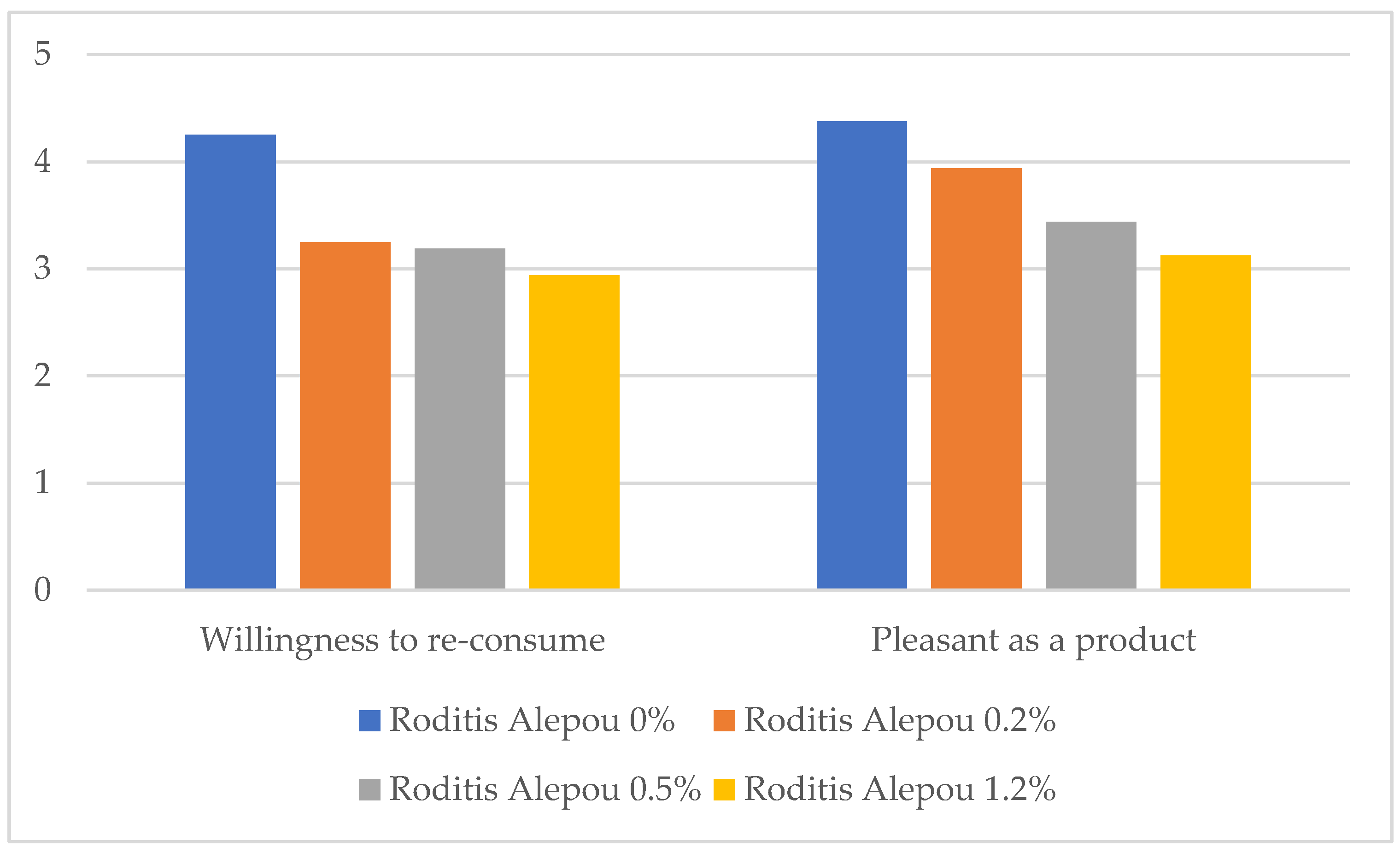

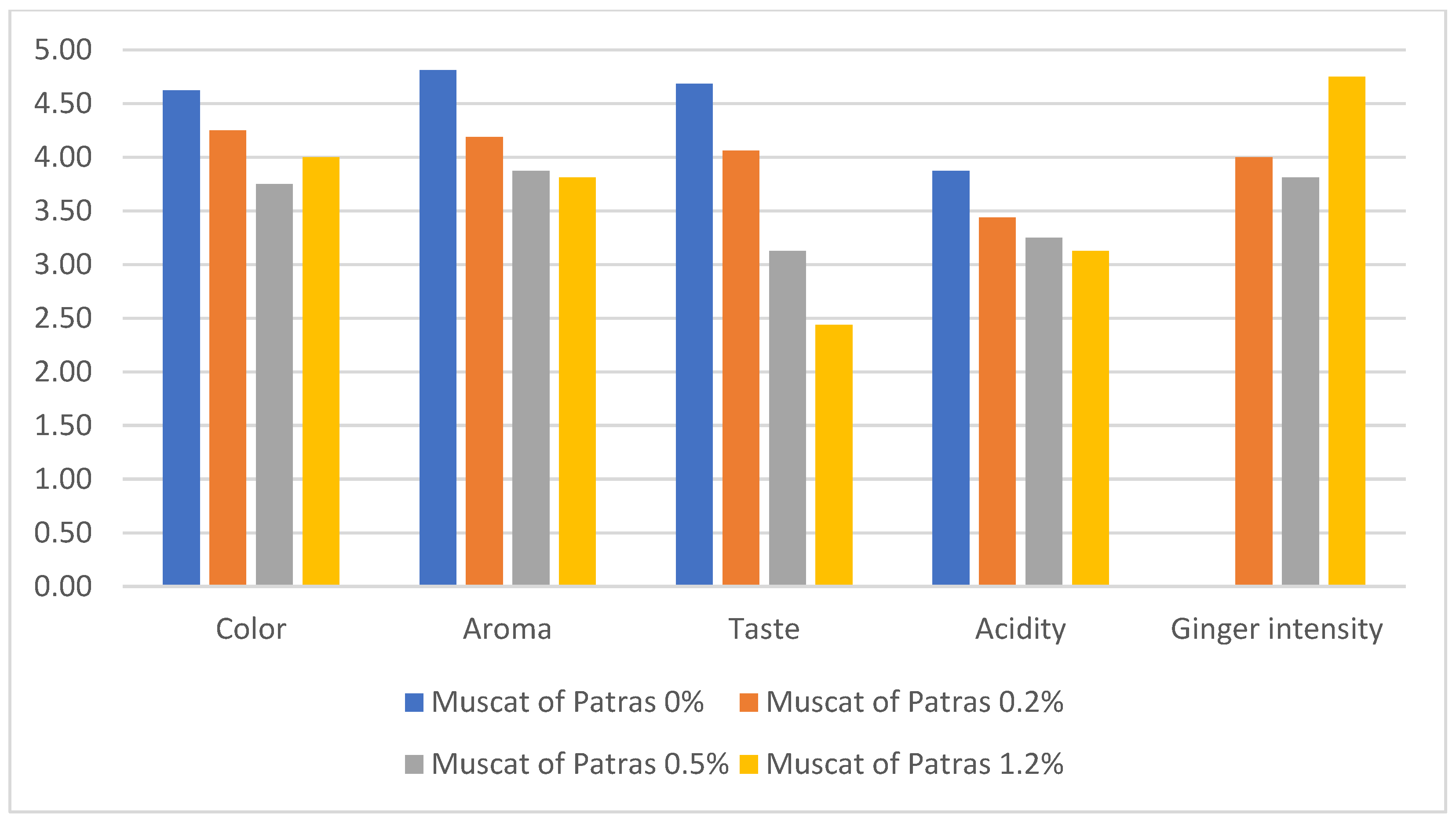

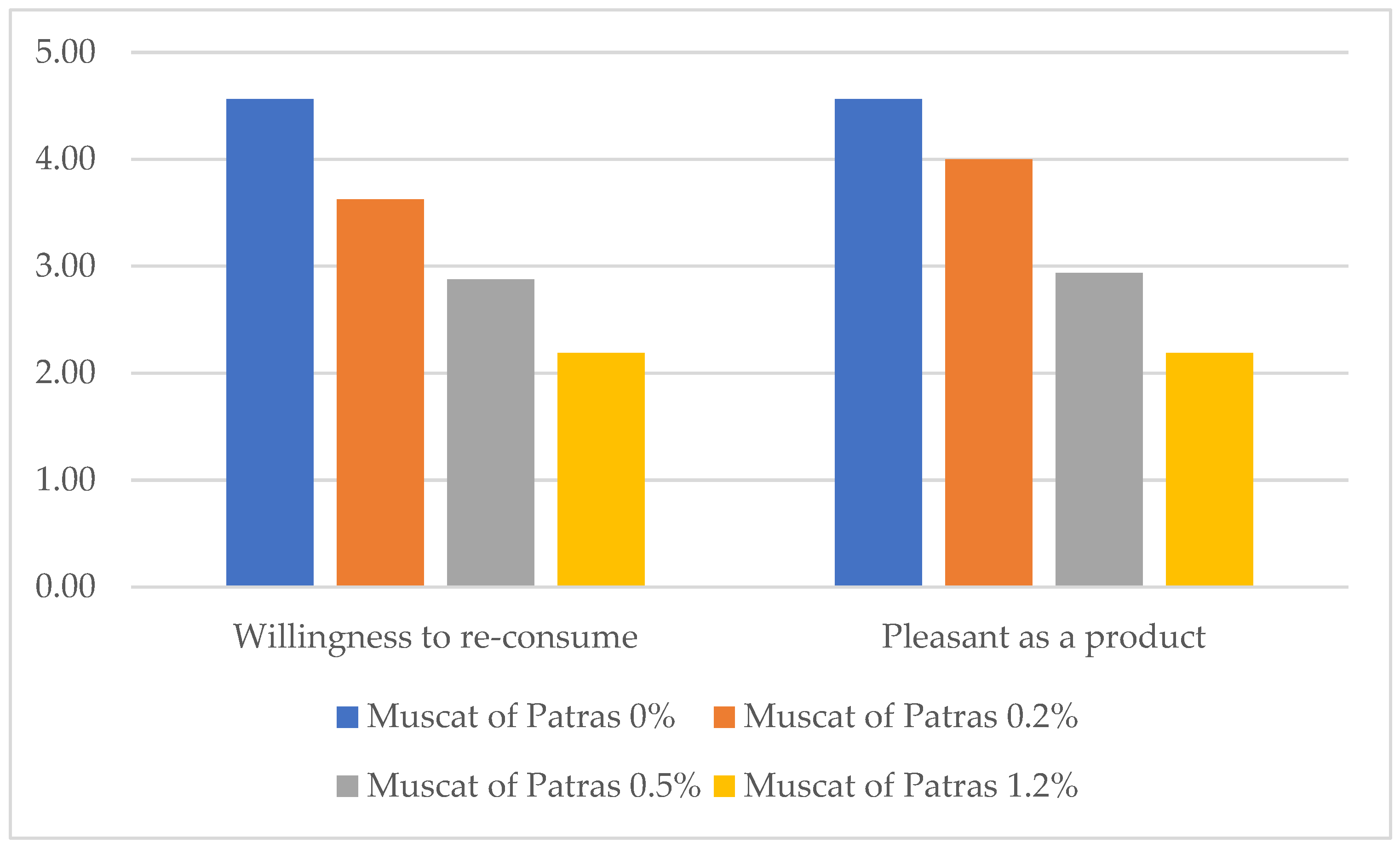

3.2. Sensory Parameters

- (i)

- 60% of panelists felt that ginger was better suited to Muscat of Patras, while 40% preferred it in Roditis Alepou.

- (ii)

- 70% of panelists do not consume ginger in their daily diets, while 30% do.

- (iii)

- 80% reported that the concentration of 0.2% (w/v) of the added ginger powder in Muscat of Patras was the most pleasant combination, compared to 20% who preferred it in Roditis Alepou.

- (iv)

- A spicy taste was noted as intense in the samples that were enriched with ginger powder at concentrations of 0.5% and 1.2% (w/v), though no significant olfactory intensity was observed in these concentrations.

- (v)

- Panelists noted a disconnection between aroma and flavor, as the ginger aroma did not accurately predict the spicy taste.

- (vi)

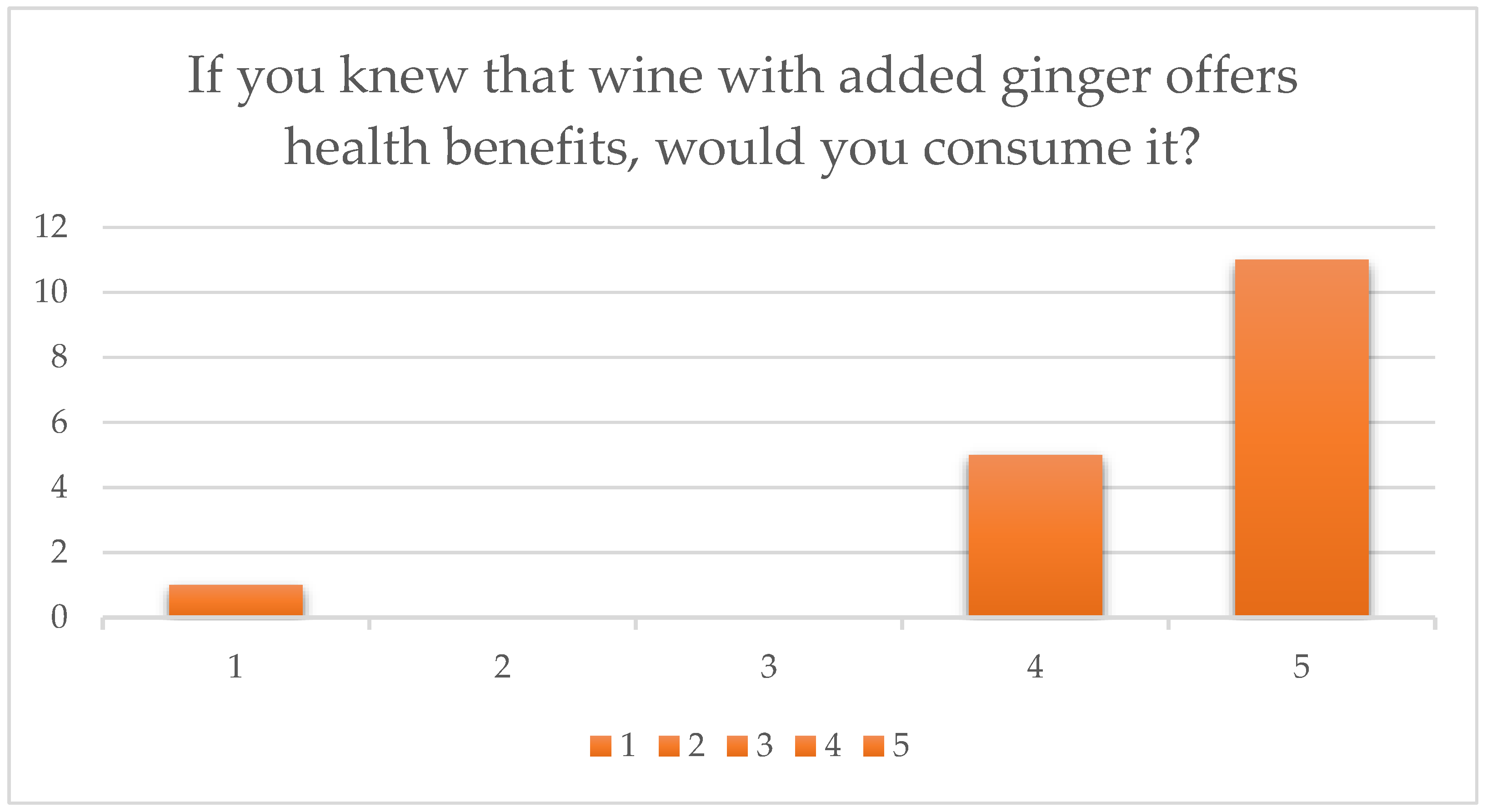

- Finally, 70% stated they would certainly consume the product if health benefits were confirmed as a health claim label (5/5), 25% answered very likely (4/5), and only 5% answered they would not consume it (1/5).

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boulay, T. Wine Appreciation in Ancient Greece. In A Companion to Food in the Ancient World, 1st ed.; Wilkins, J.A., Nadeau, R.B., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: London, UK, 2015; pp. 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrikopoulos, N. Wine. In Trofognosia; Moscos, P., Ed.; Kallipos: Athens, Greece, 2015; pp. 386–395. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/11419/4717 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- New, A.A.; Haling, N.N. Preparation, Characterization of Orange Wine and Comparison of Some Physical Parameters of Different Wines. Korea Conf. Res. J. 2019, 3, 1227–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buican, B.-C.; Colibaba, L.C.; Luchian, C.E.; Kallithraka, S.; Cotea, V.V. “Orange” Wine—The Resurgence of an Ancient Winemaking Technique: A Review. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilford, J.M.; Pezzuto, J.M. Wine and Health: A Review. AJEV 2011, 62, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Buelga, C.; González-Manzano, S.; González-Paramás, A.M. White wine polyphenols and health. In White Wine Technology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bober, Z.; Stępień, A.; Aebisher, D.; Ożog, L.; Bartusik-Aebisher, D. Medicinal benefits from the use of Black pepper, Curcuma and Ginger. Eur. J. Clin. Med. 2018, 2, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballester, P.; Cerdá, B.; Arcusa, R.; Marhuenda, J.; Yamedjeu, K.; Zafrilla, P. Effect of Ginger on Inflammatory Diseases. Molecules 2022, 27, 7223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bag, B.B. Ginger Processing in India (Zingiber officinale): A Review. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci. 2018, 7, 1639–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intzirtzi, E.; Karabagias, V.K.; Lazaridis, D.G.; Karabagias, I.K.; Giannakas, E.A. Characterization of the physicochemical, phytochemical, and microbiological properties of steam cooked beetroots during refrigerated storage. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2024, 250, 1733–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC International. AOAC Official Method 962.12. Acidity (Titratable) of Wine. In Official Methods of Analysis, 16th ed.; AOAC International: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lazaridis, D.G.; Karabagias, V.K.; Karabagias, I.K.; Andritsos, N.D.; Giannakas, A.E. Physicochemical and Phytochemical Characterization of Green Coffee, Cinnamon Clove, and Nutmeg EEGO, and Aroma Evaluation of the Raw Powders. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2024, 250, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitsios, A.-P.M.; Lazaridis, D.G.; Koutoulis, A.S.; Karabagias, V.K.; Andritsos, N.D.; Karabagias, I.K. Geographical Origin Estimation of Miniaturized Samples of “Nova” Mandarin Juice Based on Multiple Physicochemical and Biochemical Parameters Conjointly with Bootstrapping. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2025, 251, 1005–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heymann, H.; Machado, B.; Torri, L.; Robinson, A.L. How Many Judges Should One Use for Sensory Descriptive Analysis? J. Sens. Stud. 2012, 27, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roufa, P.; Evangelou, A.; Beris, E.; Karagianni, S.; Chatzilazarou, A.; Dourtoglou, E.; Shehadeh, A. Increase in Total Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Capacity in Wines with Pre- and Post-Fermentation Addition of Melissa officinalis, Salvia officinalis and Cannabis sativa. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jangra, M.R.; Kumar, R.; Jangra, S.; Jain, A.; Nehra, K.S. Production and Characterization of Wine from Ginger, Honey and Sugar blends. GJBB 2018, 7, 74–80. [Google Scholar]

- Sęczyk, Ł.; Gawlik-Dziki, U.; Świeca, M. Influence of Phenolic-Food Matrix Interactions on In Vitro Bioaccessibility of Selected Phenolic Compounds and Nutrients Digestibility in Fortified White Bean Paste. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahidi, F.; Dissanayaka, C.S. Phenolic-Protein Interactions: Insight from In-Silico Analyses—A Review. Food Prod. Process. Nutr. 2023, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdal, T.; Capanoglu, E.; Altay, F. A Review on Protein–Phenolic Interactions and Associated Changes. Food Res. Int. 2013, 51, 954–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieserling, H.; de Bruijn, W.J.C.; Keppler, J.; Yang, J.; Sagu, S.T.; Güterbock, D.; Rawel, H.; Schwarz, K.; Vincken, J.; Schieber, A.; et al. Protein–Phenolic Interactions and Reactions: Discrepancies, Challenges, and Opportunities. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2024, 23, e70015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakićević, S.H.; Karabegović, I.T.; Cvetković, D.J.; Lazić, M.L.; Jančić, R.; Popović-Djordjević, J.B. Insight into the Aroma Profile and Sensory Characteristics of ‘Prokupac’ Red Wine Aromatised with Medicinal Herbs. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dordević, D.; Jancikova, S.; Tremlová, B. Antioxidant profile of mulled wine. Potr. Slov. J. Food. Sci 2019, 13, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amponsah, O.P.; Goyal, P.; Jangra, R.M. Medicinal Enhancement and Sensory Analysis of Dates Fruit Wine. Int. J. Biol. Res. 2019, 9, 149–156. [Google Scholar]

- Akubor, P.I.; Obio, S.O.; Nwadomere, K.A.; Obiomah, E. Production and quality evaluation of banana wine. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2003, 58, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soibam, H.; Singh Ayam, V.; Chakraborty, I. Evaluation of wine prepared from sugarcane and watermelon juice. J. Ferment. Technol. 2016, 6, 475–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogodo, C.A.; Ugbogu, C.O.; Ugbogu, E.A.; Ezeonu, C.S. Production of mixed fruit (pawpaw, banana and watermelon) wine using Saccharomyces cerevisiae isolated from palm wine. SpringerPlus 2015, 4, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahapatra, S.D.; Sahoo, P.K.; De, J.; Goswami, S.; Manna, S.; De, S. Phytochemical Analysis of Ginger Raisin Wine and its Fermetation Process: Investigating Antibacterial Properties. J. Phytopharmacol. 2023, 12, 311–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiradhonkar, R.; Dukare, A.; Jawalekar, K.; Magar, P.; Jadhav, H. Fortification of Wine with Herbal Extracts: Production, Evaluation and Therapeutic applications of such Fortified Wines. IOSR J. Environ. Sci. Toxicol. Food Technol. 2014, 8, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh Sekhon, A.; Kaur, P. Production Of Ginger- and Aloe Vera-Based Herbal Wines and Their Antimicrobial Profiling. Appl. Biol. Res. 2023, 25, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malomo, A.A.; Obayomi, O.V.; Akala, J.M.; Olaniran, A.F.; Adeniran, H.A.; Abiose, S.H. Influence of Bio and Chemical Preservative on Microbiological, Sensory Properties and Antioxidant Activity of Ginger-Flavored Plantain Wine for Food Waste Prevention Strategy. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 21, 101902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ying, C.; He, C.; Wei, M. Effects of Gingerols on Yeast Growth and Metabolism of the Fermentation Process. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1637, 012107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Must | Ginger Powder Concentration | pH | Acidity (g/L) | AA (%) | A420 | A520 | A620 | TPC1 (mg GAE/L) | TPC2 (mg GAE/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muscat of Patras | 0% | 3.58 ± 0.01 a | 5.3 ± 0.0 a | 65 ± 0 a | 0.4 ± 0.0 a | 0.4 ± 0.2 a | 0.2 ± 0.0 a | 16 ± 16 a | 61 ± 63 a |

| Muscat of Patras | 0.2% | 3.61 ± 0.01 b | 5.0 ± 0.1 a | 76 ± 0 b | 0.6 ± 0.0 b | 0.4 ± 0.0 a | 0.4 ± 0.0 b | 23 ± 25 a | 70 ± 24 a |

| Muscat of Patras | 0.5% | 3.63 ± 0.01 c | 5.0 ± 0.5 a | 75 ± 0 c | 0.3 ± 0.0 c | 0.3 ± 0.2 a | 0.2 ± 0.1 a | 25 ± 8 a | 162 ± 38 a |

| Muscat of Patras | 1.2% | 3.68 ± 0.01 d | 4.9 ± 0.1 a | 75 ± 0 d | 0.4 ± 0.0 a | 0.2 ± 0.0 a | 0.2 ± 0.0 a | 54 ± 33 a | 96 ± 61 a |

| Roditis Alepou | 0% | 3.80 ± 0.01 a | 4.2 ± 0.1 a | 80 ± 0 a | 0.4 ± 0.0 a | 0.3 ± 0.0 a | 0.2 ± 0.0 a | 0 ± 0 a | 0 ± 0 a |

| Roditis Alepou | 0.2% | 3.82 ± 0.01 b | 4.3 ± 0.1 a | 80 ± 0 b | 0.5 ± 0.0 b | 0.4 ± 0.0 b | 0.4 ± 0.0 b | 0 ± 0 a | 0 ± 0 a |

| Roditis Alepou | 0.5% | 3.84 ± 0.01 c | 4.2 ± 0.0 a | 82 ± 0 c | 0.2 ± 0.0 c | 0.1 ± 0.0 c | 0.1 ± 0.0 c | 0 ± 0 a | 3 ± 6 a |

| Roditis Alepou | 1.2% | 3.89 ± 0.01 d | 4.2 ± 0.1 a | 56 ± 0 d | 0.3 ± 0.0 d | 0.1 ± 0.0 c | 0.1 ± 0.0 c | 26 ± 15 b | 10 ± 9 a |

| Wine | Ginger Powder Concentration | pH | Acidity (g/L) | AA (%) | A420 | A520 | A620 | TPC1 (mg GAE/L) | TPC2 (mg GAE/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muscat of Patras | 0% | 3.76 ± 0.05 a | 6.3 ± 0.1 a | 52 ± 0 a | 0.3 ± 0.4 a | 0.0 ± 0.0 a | 0.0 ± 0.0 a | 215 ± 36 a | 265 ± 40 a |

| Muscat of Patras | 0.2% | 3.83 ± 0.04 a | 6.5 ± 0.0 a | 49 ± 4 a | 0.1 ± 0.0 a | 0.0 ± 0.0 b | 0.0 ± 0.0 a | 262 ± 43 a | 257 ± 50 a |

| Muscat of Patras | 0.5% | 3.83 ± 0.01 a | 6.5 ± 0.0 a | 51 ± 1 a | 0.1 ± 0.0 a | 0.0 ± 0.0 c | 0.0 ± 0.0 b | 221 ± 41 a | 247 ± 65 a |

| Muscat of Patras | 1.2% | 3.86 ± 0.05 a | 6.3 ± 0.3 a | 48 ± 1 a | 0.2 ± 0.0 a | 0.0 ± 0.0 d | 0.0 ± 0.0 a | 282 ± 19 a | 223 ± 21 a |

| Roditis Alepou | 0% | 3.99 ± 0.00 a | 6.0 ± 0.0 a | 52 ± 5 a | 0.1 ± 0.0 a | 0.0 ± 0.0 a | 0.0 ± 0.0 a | 158 ± 10 a | 141 ± 10 a |

| Roditis Alepou | 0.2% | 4.01 ± 0.00 b | 6.5 ± 0.0 b | 51 ± 3 a | 0.1 ± 0.0 a | 0.0 ± 0.0 a | 0.0 ± 0.0 a | 108 ± 10 b | 95 ± 24 b |

| Roditis Alepou | 0.5% | 4.03 ± 0.00 c | 6.4 ± 0.1 b | 52 ± 5 a | 0.2 ± 0.0 b | 0.0 ± 0.0 a | 0.0 ± 0.0 a | 113 ± 17 b | 118 ± 11 b |

| Roditis Alepou | 1.2% | 4.09 ± 0.00 d | 6.5 ± 0.1 b | 45 ± 2 a | 0.2 ± 0.0 c | 0.1 ± 0.0 b | 0.0 ± 0.0 a | 83 ± 8 c | 90 ± 7 b |

| Wine | Ginger Extract Concentration | pH | Acidity (g/L) | AA (%) | A420 | A520 | A620 | TPC1 (mg GAE/L) | TPC2 (mg GAE/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muscat of Patras | 0% | 3.76 ± 0.05 a | 6.3 ± 0.1 a | 52 ± 0 a | 0.3 ± 0.4 a | 0.0 ± 0.0 a | 0.0 ± 0.0 a | 215 ± 36 a | 265 ± 40 a |

| Muscat of Patras | 0.2% | 3.95 ± 0.06 b | 6.4 ± 0.1 a | 48 ± 1 b | 0.1 ± 0.0 a | 0.0 ± 0.0 a | 0.0 ± 0.0 a | 127 ± 15 b | 126 ± 22 b |

| Muscat of Patras | 0.5% | 4.01 ± 0.01 b | 6.4 ± 0.2 a | 47 ± 3 b | 0.2 ± 0.0 a | 0.0 ± 0.0 a | 0.0 ± 0.0 a | 162 ± 17 b | 172 ± 5 b |

| Muscat of Patras | 1.2% | 4.00 ± 0.01 b | 6.8 ± 0.1 b | 50 ± 1 b | 0.3 ± 0.0 a | 0.1 ± 0.1 b | 0.1 ± 0.0 b | 143 ± 19 b | 176 ± 1 b |

| Roditis Alepou | 0% | 3.99 ± 0.00 a | 6.0 ± 0.0 a | 52 ± 5 a | 0.1 ± 0.0 a | 0.2 ± 0.1 a | 0.0 ± 0.0 a | 161 ± 14 a | 152 ± 27 a |

| Roditis Alepou | 0.2% | 3.93 ± 0.02 b | 5.8 ± 0.2 a | 47 ± 3 a | 0.2 ± 0.0 b | 0.0 ± 0.0 a | 0.0 ± 0.0 a | 109 ± 3 b | 137 ± 8 a |

| Roditis Alepou | 0.5% | 3.97 ± 0.02 b | 6.1 ± 0.2 a | 48 ± 3 a | 0.2 ± 0.0 b | 0.3 ± 0.2 b | 0.03 ± 0.03 a | 111 ± 10 b | 141 ± 34 a |

| Roditis Alepou | 1.2% | 3.96 ± 0.00 b | 6.0 ± 0.1 a | 49 ± 1 a | 0.2 ± 0.0 b | 0.1 ± 0.0 b | 0.03 ± 0.03 a | 135 ± 35 ab | 149 ± 38 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mavrogianni, T.; Intzirtzi, E.; Karabagias, V.K.; Lazaridis, D.G.; Andritsos, N.D.; Triantafyllidis, V.; Karabagias, I.K. Preparation of “Ginger-Enriched Wine” and Study of Its Physicochemical and Organoleptic Stability. Beverages 2025, 11, 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11060170

Mavrogianni T, Intzirtzi E, Karabagias VK, Lazaridis DG, Andritsos ND, Triantafyllidis V, Karabagias IK. Preparation of “Ginger-Enriched Wine” and Study of Its Physicochemical and Organoleptic Stability. Beverages. 2025; 11(6):170. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11060170

Chicago/Turabian StyleMavrogianni, Theodora, Eirini Intzirtzi, Vassilios K. Karabagias, Dimitrios G. Lazaridis, Nikolaos D. Andritsos, Vassilios Triantafyllidis, and Ioannis K. Karabagias. 2025. "Preparation of “Ginger-Enriched Wine” and Study of Its Physicochemical and Organoleptic Stability" Beverages 11, no. 6: 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11060170

APA StyleMavrogianni, T., Intzirtzi, E., Karabagias, V. K., Lazaridis, D. G., Andritsos, N. D., Triantafyllidis, V., & Karabagias, I. K. (2025). Preparation of “Ginger-Enriched Wine” and Study of Its Physicochemical and Organoleptic Stability. Beverages, 11(6), 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11060170