Ticagrelor Versus Prasugrel in Acute Coronary Syndrome: Real-World Treatment and Safety

Abstract

1. Introduction

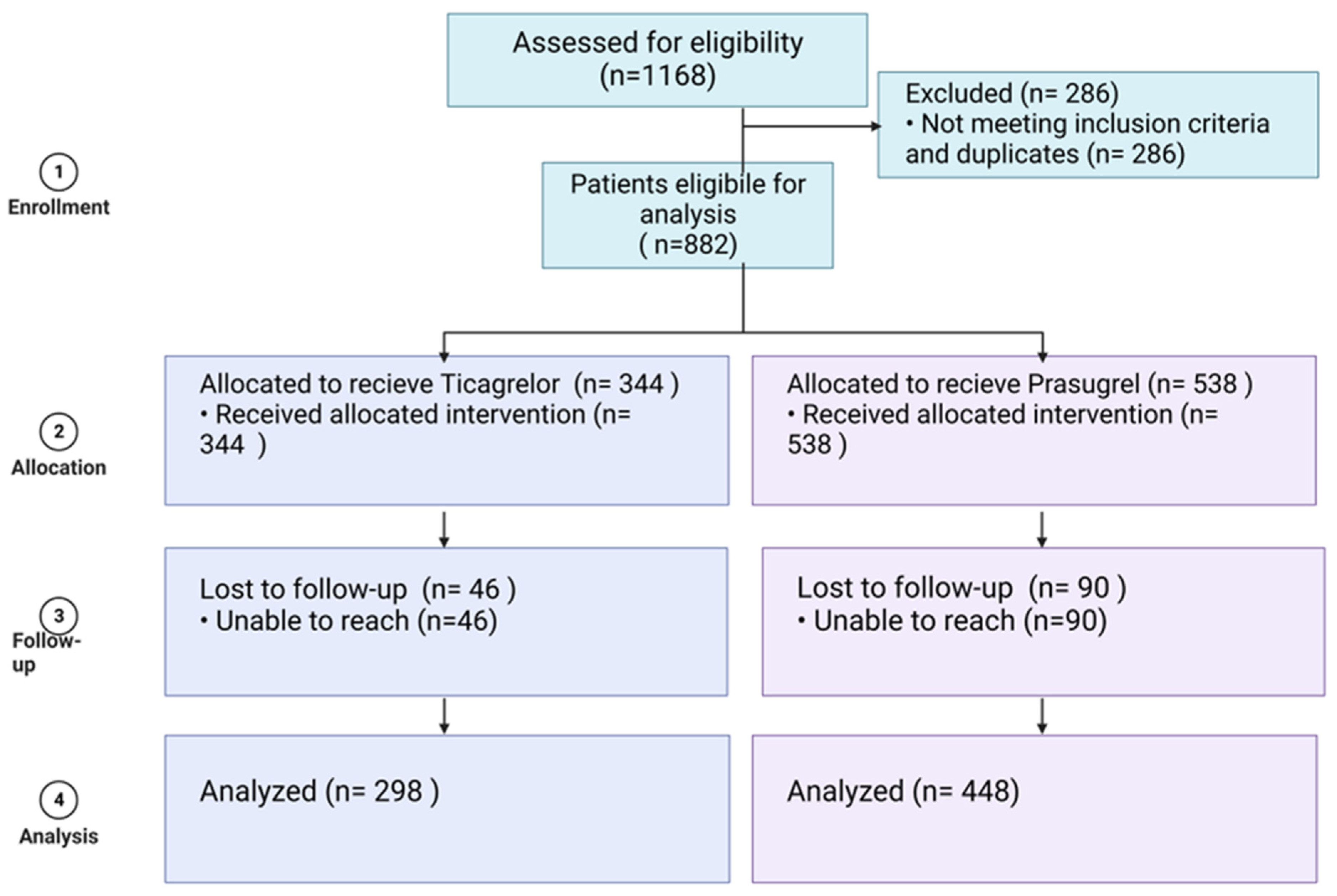

2. Methods

2.1. Study Population

- Unstable angina pectoris—ICD-10 code I20;

- ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI)—ICD-10 codes I21.0/I21.1/I21.2 or I21.3;

- Non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI)—ICD-10 code I21.4.

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Study Endpoints

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Primary Endpoint

5. Discussion

- This is a single-center retrospective study. Some patients were excluded because of incomplete data, and about 15% of the patients were lost to the one-year follow-up, which might have affected the data. Furthermore, there were more patients on prasugrel than ticagrelor, yet this is within the calculated sample size, powered to detect efficacy difference, and results from clinical judgment based on the current guidelines.

- Because of the retrospective nature of the study, the study may have been affected by selection bias. Furthermore, some differences were seen between the two groups’ baseline characteristics. The patients in the prasugrel group were younger and the absolute majority of them were admitted with a diagnosis of myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation, while in the ticagrelor group, a diagnosis of myocardial infarction without ST elevations was more common. This was implemented due to the acceptable department protocols at that time, which allowed treatment of younger patients (up to the age of 75) with a myocardial infarction and ST elevations with prasugrel, while older patients or those who were admitted due myocardial infarction without ST elevations were to be treated with ticagrelor. At the same time, there was a large group of patients with unstable angina who were not treated with potent antiplatelets but with clopidogrel. This group was not included in this study. So, it is not possible to rule out a certain bias that may exist in favor of each tested drug.

- The management of patients who discontinued the drug before the end of the year was not evaluated. We do not have enough data about why and when the treatment was stopped.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brown, J.C.; Gerhardt, T.E.; Kwon, E. Risk Factors for Coronary Artery Disease; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Task Force on the management of STseamiotESoC; Steg, P.G.; James, S.K.; Atar, D.; Badano, L.P.; Lundqvist, C.B.; Borger, M.A.; Di Mario, C.; Dickstein, K.; Ducrocq, G.; et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 2569–2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roffi, M.; Patrono, C.; Collet, J.P.; Mueller, C.; Valgimigli, M.; Andreotti, F.; Bax, J.J.; Borger, M.A.; Brotons, C.; Chew, D.P.; et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: Task Force for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients Presenting without Persistent ST-Segment Elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 267–315. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Levine, G.N.; Bates, E.R.; Bittl, J.A.; Brindis, R.G.; Fihn, S.D.; Fleisher, L.A.; Granger, C.B.; Lange, R.A.; Mack, M.J.; Mauri, L.; et al. 2016 ACC/AHA Guideline Focused Update on Duration of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy in Patients With Coronary Artery Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 68, 1082–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrono, C.; Andreotti, F.; Arnesen, H.; Badimon, L.; Baigent, C.; Collet, J.P.; De Caterina, R.; Gulba, D.; Huber, K.; Husted, S.; et al. Antiplatelet agents for the treatment and prevention of atherothrombosis. Eur. Heart J. 2011, 32, 2922–2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiviott, S.D.; Braunwald, E.; McCabe, C.H.; Montalescot, G.; Ruzyllo, W.; Gottlieb, S.; Neumann, F.J.; Ardissino, D.; De Servi, S.; Murphy, S.A.; et al. Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 2001–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurbel, P.A.; Bliden, K.P.; Butler, K.; Tantry, U.S.; Gesheff, T.; Wei, C.; Teng, R.; Antonino, M.J.; Patil, S.B.; Karunakaran, A.; et al. Randomized double-blind assessment of the ONSET and OFFSET of the antiplatelet effects of ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with stable coronary artery disease: The ONSET/OFFSET study. Circulation 2009, 120, 2577–2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, J.T.; Payne, C.D.; Wiviott, S.D.; Weerakkody, G.; Farid, N.A.; Small, D.S.; Jakubowski, J.A.; Naganuma, H.; Winters, K.J. A comparison of prasugrel and clopidogrel loading doses on platelet function: Magnitude of platelet inhibition is related to active metabolite formation. Am. Heart J. 2007, 153, 66 e9-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schüpke, S.; Neumann, F.J.; Menichelli, M.; Mayer, K.; Bernlochner, I.; Wöhrle, J.; Richardt, G.; Liebetrau, C.; Witzenbichler, B.; Antoniucci, D.; et al. Ticagrelor or Prasugrel in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1524–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, D.A.; Wiviott, S.D.; White, H.D.; Nicolau, J.C.; Bramucci, E.; Murphy, S.A.; Bonaca, M.P.; Ruff, C.T.; Scirica, B.M.; McCabe, C.H.; et al. Effect of the novel thienopyridine prasugrel compared with clopidogrel on spontaneous and procedural myocardial infarction in the Trial to Assess Improvement in Therapeutic Outcomes by Optimizing Platelet Inhibition with Prasugrel-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 38: An application of the classification system from the universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation 2009, 119, 2758–2764. [Google Scholar]

- Wiviott, S.D.; Antman, E.M.; Gibson, C.M.; Montalescot, G.; Riesmeyer, J.; Weerakkody, G.; Winters, K.J.; Warmke, J.W.; McCabe, C.H.; Braunwald, E.; et al. Evaluation of prasugrel compared with clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes: Design and rationale for the TRial to assess Improvement in Therapeutic Outcomes by optimizing platelet InhibitioN with prasugrel Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction 38 (TRITON-TIMI 38). Am. Heart J. 2006, 152, 627–635. [Google Scholar]

- Jernberg, T.; Payne, C.D.; Winters, K.J.; Darstein, C.; Brandt, J.T.; Jakubowski, J.A.; Naganuma, H.; Siegbahn, A.; Wallentin, L. Prasugrel achieves greater inhibition of platelet aggregation and a lower rate of non-responders compared with clopidogrel in aspirin-treated patients with stable coronary artery disease. Eur. Heart J. 2006, 27, 1166–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindholm, D.; Varenhorst, C.; Cannon, C.P.; Harrington, R.A.; Himmelmann, A.; Maya, J.; Husted, S.; Steg, P.G.; Cornel, J.H.; Storey, R.F.; et al. Ticagrelor vs. clopidogrel in patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome with or without revascularization: Results from the PLATO trial. Eur. Heart J. 2014, 35, 2083–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goto, S.; Huang, C.H.; Park, S.J.; Emanuelsson, H.; Kimura, T. Ticagrelor vs. clopidogrel in Japanese, Korean and Taiwanese patients with acute coronary syndrome–randomized, double-blind, phase III PHILO study. Circ. J. 2015, 79, 2452–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gimbel, M.; Qaderdan, K.; Willemsen, L.; Hermanides, R.; Bergmeijer, T.; de Vrey, E.; Heestermans, T.; Gin, M.T.J.; Waalewijn, R.; Hofma, S.; et al. Clopidogrel versus ticagrelor or prasugrel in patients aged 70 years or older with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome (POPular AGE): The randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2020, 395, 1374–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, N.; Krefting, J.; Kessler, T.; Schmieder, R.; Starnecker, F.; Dutsch, A.; Graesser, C.; Meyer-Lindemann, U.; Storz, T.; Pugach, I.; et al. Ticagrelor vs Prasugrel for Acute Coronary Syndrome in Routine Care. JAMA Netw. Open. 2024, 7, e2448389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coughlan, J.J.; Aytekin, A.; Lahu, S.; Ndrepepa, G.; Menichelli, M.; Mayer, K.; Wöhrle, J.; Bernlochner, I.; Gewalt, S.; Witzenbichler, B.; et al. Ticagrelor or Prasugrel for Patients With Acute Coronary Syndrome Treated With Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: A Prespecified Subgroup Analysis of a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2021, 6, 1121–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, L.C.W.; Lee, N.H.C.; Yan, A.T.; Ng, M.Y. Comparison of Prasugrel and Ticagrelor for Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cardiology 2022, 147, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.L.; Lin, Y.; Chen, D.Y.; Lin, M.S.; Wang, C.Y.; Hsieh, I.C.; Yang, N.I.; Hung, M.J.; Chen, T.H. Ticagrelor versus Adjusted-Dose Prasugrel in Acute Coronary Syndrome with Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2024, 116, 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.P.; Shafiq, A.; Hamza, M.; Maniya, M.T.; Duhan, S.; Keisham, B.; Patel, B.; Alamzaib, S.M.; Yashi, K.; Uppal, D.; et al. Ticagrelor Versus Prasugrel in Patients With Acute Coronary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Cardiol. 2023, 207, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valgimigli, M.; Gragnano, F.; Branca, M.; Franzone, A.; Da Costa, B.R.; Baber, U.; Kimura, T.; Jang, Y.; Hahn, J.Y.; Zhao, Q.; et al. Ticagrelor or Clopidogrel Monotherapy vs Dual Antiplatelet Therapy After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: A Systematic Review and Patient-Level Meta-Analysis. JAMA Cardiol. 2024, 9, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Abdouh, A.; Barbarawi, M.; Abusnina, W.; Amr, M.; Zhao, D.; Savji, N.; Hasan, R.K.; Michos, E.D. Prasugrel vs Ticagrelor for DAPT in Patients with ACS Undergoing PCI: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Cardiovasc. Revasc. Med. 2020, 21, 1613–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.S.; Memon, M.M.; Usman, M.S.; Alnaimat, S.; Khan, S.U.; Khan, A.R.; Yamani, N.; Fugar, S.; Mookadam, F.; Krasuski, R.A.; et al. Prasugrel vs. Ticagrelor for Acute Coronary Syndrome Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Drugs 2019, 19, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexopoulos, D.; Galati, A.; Xanthopoulou, I.; Mavronasiou, E.; Kassimis, G.; Theodoropoulos, K.C.; Makris, G.; Damelou, A.; Tsigkas, G.; Hahalis, G.; et al. Ticagrelor versus prasugrel in acute coronary syndrome patients with high on-clopidogrel platelet reactivity following percutaneous coronary intervention: A pharmacodynamic study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012, 60, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collet, J.P.; Thiele, H.; Barbato, E.; Barthélémy, O.; Bauersachs, J.; Bhatt, D.L.; Dendale, P.; Dorobantu, M.; Edvardsen, T.; Folliguet, T.; et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 1289–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

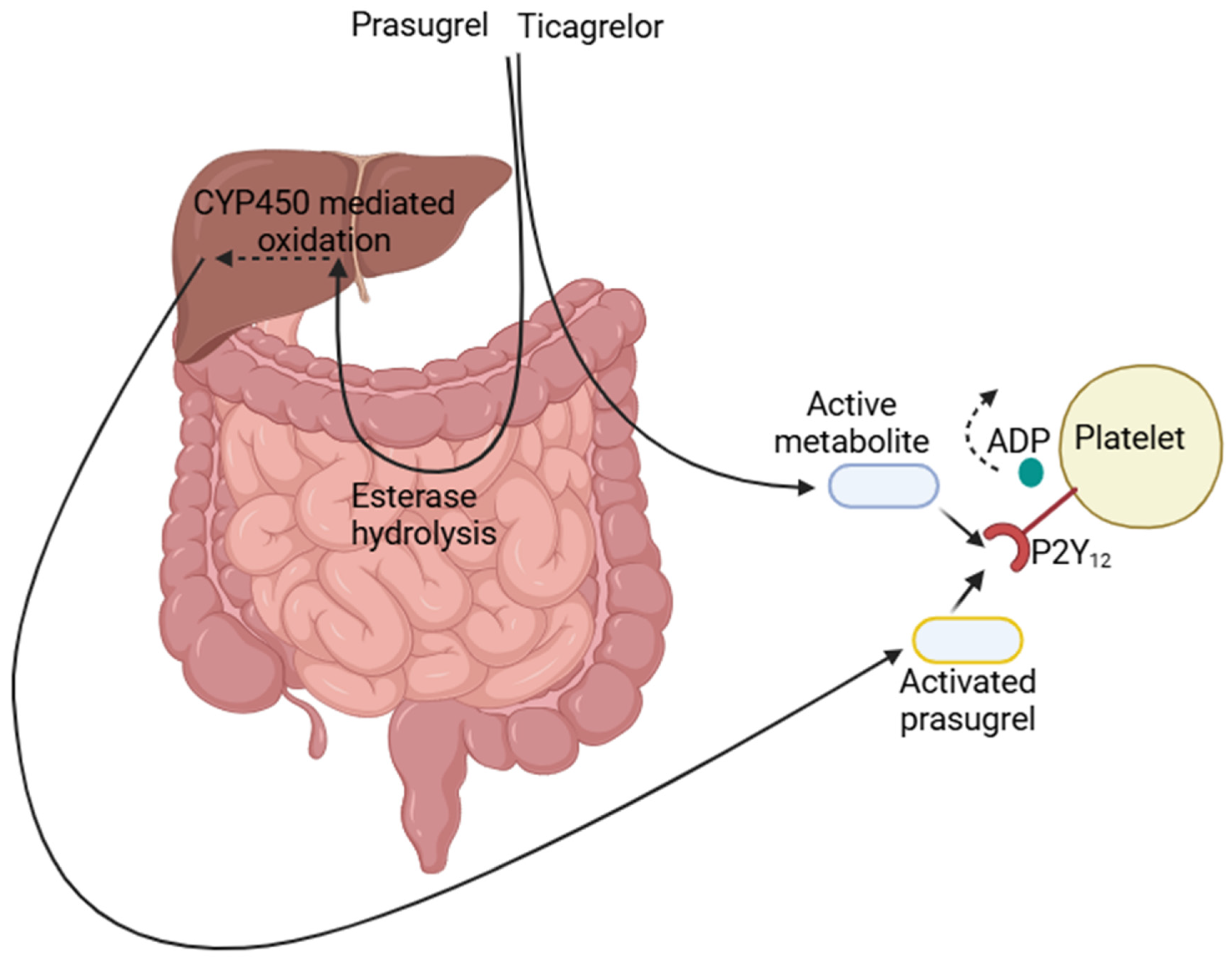

- Dobesh, P.P. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of prasugrel, a thienopyridine P2Y12 inhibitor. Pharmacotherapy 2009, 29, 1089–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.M.; Wang, Z.N.; Chen, X.W.; Zhang, H.L.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, Y. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of single and multiple doses of prasugrel in healthy native Chinese subjects. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2012, 33, 1395–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobesh, P.P.; Oestreich, J.H. Ticagrelor: Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, clinical efficacy, and safety. Pharmacotherapy 2014, 34, 1077–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalescot, G.; Bolognese, L.; Dudek, D.; Goldstein, P.; Hamm, C.; Tanguay, J.F.; Ten Berg, J.M.; Miller, D.L.; Costigan, T.M.; Goedicke, J.; et al. Pretreatment with prasugrel in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 999–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndrepepa, G.; Kastrati, A.; Menichelli, M.; Neumann, F.J.; Wöhrle, J.; Bernlochner, I.; Richardt, G.; Witzenbichler, B.; Sibbing, D.; Gewalt, S.; et al. Ticagrelor or Prasugrel in Patients With Acute Coronary Syndromes and Diabetes Mellitus. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2020, 13, 2238–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aytekin, A.; Scalamogna, M.; Coughlan, J.J.; Lahu, S.; Ndrepepa, G.; Menichelli, M.; Mayer, K.; Wöhrle, J.; Bernlochner, I.; Witzenbichler, B.; et al. Incidence and pattern of urgent revascularization in acute coronary syndromes treated with ticagrelor or prasugrel. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2024, 113, 1060–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, A.; Najmi, A.; Khandelwal, G.; Jhaj, R.; Sadasivam, B. Comparative effectiveness and safety of prasugrel and ticagrelor in patients of acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty: A propensity score-matched analysis. Indian Heart J. 2024, 76, 133–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venetsanos, D.; Träff, E.; Erlinge, D.; Hagström, E.; Nilsson, J.; Desta, L.; Lindahl, B.; Mellbin, L.; Omerovic, E.; Szummer, K.E.; et al. Prasugrel versus ticagrelor in patients with myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Heart 2021, 107, 1145–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Prasugrel Group (n = 448) | Ticagrelor Group (n = 298) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 57.4 ± 10.2 | 61.5 ± 10.3 | p < 0.001 |

| Female | |||

| N (%) | 49 (10.9) | 45 (15.1) | p = 0.001 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors–no. (%): | |||

| Diabetes | 130 (29) | 91 (30) | 0.67 |

| Current smoker | 221 (49.3) | 146 (49) | 0.89 |

| Past smoker | 63 (14) | 41 (13.7) | 0.89 |

| Arterial hypertension | 258 (57.6) | 174 (58.3) | 0.87 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 292 (65.2) | 197 (66.1) | 0.84 |

| Family history of CAD | 99 (22) | 63 (21.1) | 0.73 |

| Background Medications–no. (%) | |||

| Insulin | 41 (9.1) | 27 (9) | 0.98 |

| ACE-I/ARBs | 261 (58.2) | 179 (60) | 0.62 |

| Beta Blockers | 88 (29.5) | 149 (33.2) | 0.28 |

| Calcium Channel Blockers | 102 (34.2) | 165 (36.8) | 0.46 |

| Aspirin | 158 (53) | 228 (50.1) | 0.57 |

| Medical history–no. (%): | |||

| Myocardial infarction | 97 (21.6) | 68 (22.8) | 0.72 |

| Aortocoronary bypass surgery | 11 (2.4) | 6 (2) | 0.68 |

| Blood pressure–mmHg | |||

| Systolic | 132 ± 5.6 | 130.8 ± 8.2 | 0.55 |

| Diastolic | 77.6 ± 4.6 | 77.8 ± 4.1 | 0.999 |

| Weight (kg) | 85.5 ± 7.7 | 84 ± 6.2 | 0.999 |

| Height (cm) | 175 ± 10.3 | 173 ± 8.6 | 0.26 |

| Hemoglobin level (g/dL) * | 13.9 ± 1.5 | 13.9 ± 1.6 | 0.99 |

| Creatinine level (mg/dL) ** | 0.9 ± 0.4 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 0.99 |

| Diagnosis at admission–no. (%): | p < 0.001 | ||

| STEMI | 393 (87.7) | 47 (15.7) | |

| NON-STEMI | 28 (6.3) | 203 (68.1) | |

| UAP | 27 (6) | 48 (16.1) |

| Drug | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ticagrelor (n = 298) | Prasugrel (n = 448) | Total (n = 746) | p-Value | Relative Risk (95% CI) | |

| Primary outcome | |||||

| (Composite of death from a CV cause, MI, or stroke)–no. (%) | 24 (8.0) | 46 (10.3) | 70 (9.4) | 0.303 | 1.01 (0.61, 1.64) |

| Secondary outcomes | |||||

| CV death–no. (%) | 0 (0) | 5 (1.1) | 5 (0.7) | 0.13 | 0.14 (0.01, 2.45) |

| MI–no. (%) | 23 (7.7) | 35 (7.8) | 58 (7.7) | 0.9 | 0.98 (0.6, 1.6) |

| Stroke–no. (%) | 1 (0.3) | 6 (1.3) | 7 (0.9) | 0.06 | 0.25 (0.03, 2.07) |

| Major bleeding | |||||

| Primary Endpoint Ticagrelor Group (n = 24) | Primary Endpoint Prasugrel Group (n = 46) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| STEMI No. (%) | 5 (20.8) | 40 (87) | 0.995 |

| NSTEMI No. (%) | 16 (66.7) | 3 (6.5) | 0.621 |

| UAP No. (%) | 3 (12.5) | 3 (6.5) | 0.44 |

| Drug | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prasugrel (n = 448) | Ticagrelor (n = 298) | Total (n = 746) | p-Value * | |

| Secondary endpoint η– no. (%) | 13 (2.9) | 9 (3) | 22 (2.9) | 0.9 NS ‡ |

| Prasugrel | Ticagrelor | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Allergy | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| Adverse effects | 2 | 13 | 15 |

| Underwent CABG | 3 | 5 | 8 |

| Indication for oral anticoagulation | 1 | 5 | 6 |

| Lack of adherence/medication stopped for medical reason | 9 | 13 | 22 |

| CVA/TIA | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Bleeding | 12 | 12 | 24 |

| Died | 8 | 0 | 8 |

| Total | 43 (9.6%) | 50 (16.8%) | 93 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bahouth, F.; Chutko, B.; Sholy, H.; Hassanain, S.; Zaid, G.; Radzishevsky, E.; Fahmwai, I.; Hamoud, M.; Samnia, N.; Khoury, J.; et al. Ticagrelor Versus Prasugrel in Acute Coronary Syndrome: Real-World Treatment and Safety. Medicines 2025, 12, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicines12020013

Bahouth F, Chutko B, Sholy H, Hassanain S, Zaid G, Radzishevsky E, Fahmwai I, Hamoud M, Samnia N, Khoury J, et al. Ticagrelor Versus Prasugrel in Acute Coronary Syndrome: Real-World Treatment and Safety. Medicines. 2025; 12(2):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicines12020013

Chicago/Turabian StyleBahouth, Fadel, Boris Chutko, Haitham Sholy, Sabreen Hassanain, Gassan Zaid, Evgeny Radzishevsky, Ibrahem Fahmwai, Mahmod Hamoud, Nemer Samnia, Johad Khoury, and et al. 2025. "Ticagrelor Versus Prasugrel in Acute Coronary Syndrome: Real-World Treatment and Safety" Medicines 12, no. 2: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicines12020013

APA StyleBahouth, F., Chutko, B., Sholy, H., Hassanain, S., Zaid, G., Radzishevsky, E., Fahmwai, I., Hamoud, M., Samnia, N., Khoury, J., & Dobrecky-Mery, I. (2025). Ticagrelor Versus Prasugrel in Acute Coronary Syndrome: Real-World Treatment and Safety. Medicines, 12(2), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicines12020013