Insights into Transport Function of the Murine Organic Anion-Transporting Polypeptide OATP1B2 by Comparison with Its Rat and Human Orthologues

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

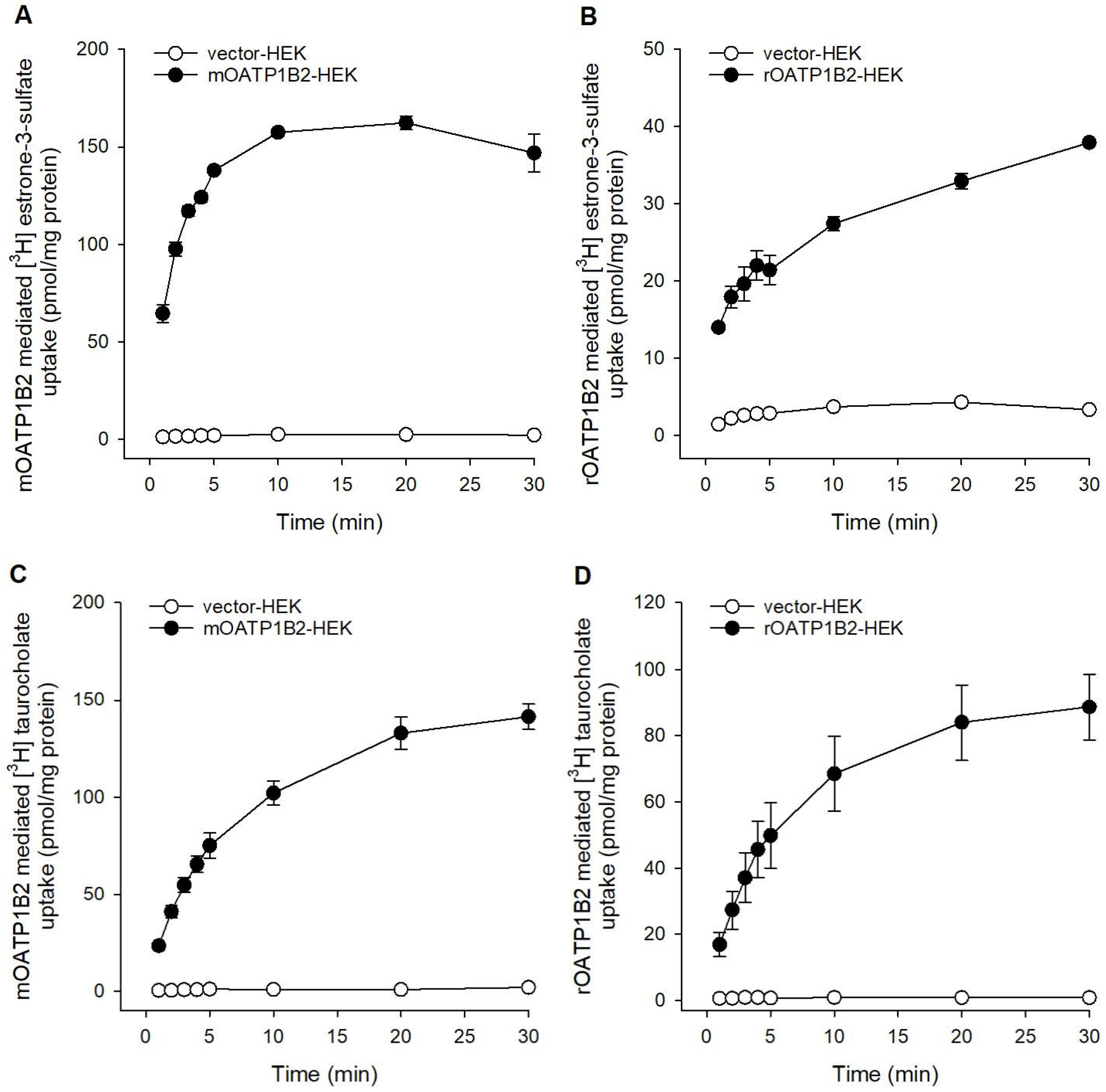

2.1. Transport Activity of Mouse and Rat OATP1B2 in Overexpressing HEK-293 Cells

2.2. Interaction of Drugs with Mouse OATP1B2 Compared to Rat OATP1B2

2.3. Concentration-Dependent Inhibitory Effects of Cyclosporine A and Rifampicin on Mouse OATP1B2 and Rat OATP1B2

2.4. Comparison of Transport Activities of Rodent OATP1B2 with the Human Orthologues hOATP1B1 and hOATP1B3

2.5. Interaction of Drugs with Human OATP1B1 and OATP1B3 Compared to Rodent OATP1B2

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Material

5.2. Methods

5.2.1. Transfection and Cell Culture

5.2.2. Transporter-Mediated Uptake of Radiolabeled Substrates

5.2.3. Inhibition Experiments

5.2.4. Determination of Protein Amount

5.2.5. Data Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ogura, K.; Choudhuri, S.; Klaassen, C.D. Full-Length cDNA Cloning and Genomic Organization of the Mouse Liver-Specific Organic Anion Transporter-1 (Lst-1). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000, 272, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer Zu Schwabedissen, H.E.; Ware, J.A.; Tirona, R.G.; Kim, R.B. Identification, Expression, and Functional Characterization of Full-Length and Splice Variants of Murine Organic Anion Transporting Polypeptide 1b2. Mol. Pharm. 2009, 6, 1790–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagenbuch, B.; Gui, C. Xenobiotic Transporters of the Human Organic Anion Transporting Polypeptides (OATP) Family. Xenobiotica 2008, 38, 778–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.M.; Zhang, L.; Giacomini, K.M. The International Transporter Consortium: A Collaborative Group of Scientists from Academia, Industry, and the FDA. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010, 87, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomini, K.M.; Huang, S.M.; Tweedie, D.J.; Benet, L.Z.; Brouwer, K.L.; Chu, X.; Dahlin, A.; Evers, R.; Fischer, V.; Hillgren, K.M.; et al. Membrane Transporters in Drug Development. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010, 9, 215–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagenbuch, B.; Meier, P.J. Organic Anion Transporting Polypeptides of the OATP/SLC21 Family: Phylogenetic Classification as OATP/SLCO Superfamily, New Nomenclature and Molecular/Functional Properties. Pflugers Arch. 2004, 447, 653–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaher, H.; Meyer zu Schwabedissen, H.E.; Tirona, R.G.; Cox, M.L.; Obert, L.A.; Agrawal, N.; Palandra, J.; Stock, J.L.; Kim, R.B.; Ware, J.A. Targeted Disruption of Murine Organic Anion-Transporting Polypeptide 1b2 (Oatp1b2/Slco1b2) Significantly Alters Disposition of Prototypical Drug Substrates Pravastatin and Rifampin. Mol. Pharmacol. 2008, 74, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattori, V.; Hagenbuch, B.; Hagenbuch, N.; Stieger, B.; Ha, R.; Winterhalter, K.E.; Meier, P.J. Identification of Organic Anion Transporting Polypeptide 4 (Oatp4) as a Major Full-Length Isoform of the Liver-Specific Transporter-1 (Rlst-1) in Rat Liver. FEBS Lett. 2000, 474, 242–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishida, K.; Ullah, M.; Tóth, B.; Juhasz, V.; Unadkat, J.D. Transport Kinetics, Selective Inhibition, and Successful Prediction of In Vivo Inhibition of Rat Hepatic Organic Anion Transporting Polypeptides. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2018, 46, 1251–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.E.; van Staden, C.J.; Chen, Y.; Kalyanaraman, N.; Kalanzi, J.; Dunn, R.T.; Afshari, C.A.; Hamadeh, H.K. A Multifactorial Approach to Hepatobiliary Transporter Assessment Enables Improved Therapeutic Compound Development. Toxicol. Sci. 2013, 136, 216–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.Q.; Liu, N.; Miwa, G.T.; Gan, L.-S. Interactions of Cyclosporin a with Breast Cancer Resistance Protein. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2007, 35, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, A.; Maeda, K.; Kamiyama, E.; Sugiyama, D.; Kondo, T.; Shiroyanagi, Y.; Nakazawa, H.; Okano, T.; Adachi, M.; Schuetz, J.D.; et al. Multiple Human Isoforms of Drug Transporters Contribute to the Hepatic and Renal Transport of Olmesartan, a Selective Antagonist of the Angiotensin II AT1-Receptor. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2007, 35, 2166–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitamura, S.; Maeda, K.; Wang, Y.; Sugiyama, Y. Involvement of Multiple Transporters in the Hepatobiliary Transport of Rosuvastatin. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2008, 36, 2014–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marada, V.V.; Florl, S.; Kuhne, A.; Burckhardt, G.; Hagos, Y. Interaction of Human Organic Anion Transporter Polypeptides 1B1 and 1B3 with Antineoplastic Compounds. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 92, 723–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirano, M.; Maeda, K.; Shitara, Y.; Sugiyama, Y. Contribution of OATP2 (OATP1B1) and OATP8 (OATP1B3) to the Hepatic Uptake of Pitavastatin in Humans. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004, 311, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gui, C.; Miao, Y.; Thompson, L.; Wahlgren, B.; Mock, M.; Stieger, B.; Hagenbuch, B. Effect of Pregnane X Receptor Ligands on Transport Mediated by Human OATP1B1 and OATP1B3. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 584, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abe, T.; Unno, M.; Onogawa, T.; Tokui, T.; Kondo, T.N.; Nakagomi, R.; Adachi, H.; Fujiwara, K.; Okabe, M.; Suzuki, T.; et al. LST-2, a Human Liver-Specific Organic Anion Transporter, Determines Methotrexate Sensitivity in Gastrointestinal Cancers. Gastroenterology 2001, 120, 1689–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyer, J.; Wilke, T.; Petzinger, E. The Solute Carrier Family SLC10: More than a Family of Bile Acid Transporters Regarding Function and Phylogenetic Relationships. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2006, 372, 413–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozawa, T.; Imai, K.; Nezu, J.-I.; Tsuji, A.; Tamai, I. Functional Characterization of pH-Sensitive Organic Anion Transporting Polypeptide OATP-B in Human. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004, 308, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussner, J.; Foletti, A.; Seibert, I.; Fuchs, A.; Schuler, E.; Malagnino, V.; Grube, M.; Meyer Zu Schwabedissen, H.E. Differences in Transport Function of the Human and Rat Orthologue of the Organic Anion Transporting Polypeptide 2B1 (OATP2B1). Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2021, 41, 100418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlgren, M.; Vildhede, A.; Norinder, U.; Wisniewski, J.R.; Kimoto, E.; Lai, Y.; Haglund, U.; Artursson, P. Classification of Inhibitors of Hepatic Organic Anion Transporting Polypeptides (OATPs): Influence of Protein Expression on Drug-Drug Interactions. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 4740–4763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fricker, G.; Drewe, J.; Huwyler, J.; Gutmann, H.; Beglinger, C. Relevance of P-Glycoprotein for the Enteral Absorption of Cyclosporin A: In Vitro-in Vivo Correlation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996, 118, 1841–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EMA. Assessment Report Bylvay-International Non-Proprietary Name Odevixibat; EMA/319560/2021; Procedure No. EMEA/H/C/004691/0000; EMA: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, R.J.; Arnell, H.; Artan, R.; Baumann, U.; Calvo, P.L.; Czubkowski, P.; Dalgic, B.; D’Antiga, L.; Durmaz, Ö.; Fischler, B.; et al. Odevixibat Treatment in Progressive Familial Intrahepatic Cholestasis: A Randomised, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 7, 830–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annaert, P.; Ye, Z.W.; Stieger, B.; Augustijns, P. Interaction of HIV Protease Inhibitors with OATP1B1, 1B3, and 2B1. Xenobiotica 2010, 40, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeer, L.M.M.; Isringhausen, C.D.; Ogilvie, B.W.; Buckley, D.B. Evaluation of Ketoconazole and Its Alternative Clinical CYP3A4/5 Inhibitors as Inhibitors of Drug Transporters: The In Vitro Effects of Ketoconazole, Ritonavir, Clarithromycin, and Itraconazole on 13 Clinically-Relevant Drug Transporters. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2016, 44, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagos, Y.; Stein, D.; Ugele, B.; Burckhardt, G.; Bahn, A. Human Renal Organic Anion Transporter 4 Operates as an Asymmetric Urate Transporter. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2007, 18, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradford, M.M. A Rapid and Sensitive Method for the Quantitation of Microgram Quantities of Protein Utilizing the Principle of Protein-Dye Binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| mOATP1B2 | rOATP1B2 | hOATP1B1 | hOATP1B3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein length (amino acids) | 689 | 687 | 691 | 702 | ||||

| Identity to mOATP1B2 (%) | 100 | 81.46 | 64.23 | 66.18 | ||||

| Probe substrates | E1S | TCA | E1S | TCA | E1S | TCA | E1S | TCA |

| Km (µM) | 242 ± 23 | 73 ± 11 | 90 ± 11 | 16 ± 3 | 0.25 ± 0.04 [14] | Uptake < 2 | no substrate | 21 ± 8 |

| Inhibitory effects at 10 µM of the drug (%) | ||||||||

| Cyclosporine A | 91 | 81 | 98 | 94 | 88 | - | - | 98 |

| Rifampicin | 44 | 53 | 93 | 83 | 59 | - | - | 104 |

| Ritonavir | 74 | 71 | 84 | 78 | 44 | - | - | 85 |

| Odevixibat | 69 | 54 | 82 | 74 | 96 | - | - | 102 |

| Rosuvastatin | 50 | 52 | 73 | 69 | 16 | - | - | 24 |

| Ketoconazole | 41 | 29 | 34 | 19 | 25 | - | - | 23 |

| Olmesartan | 18 | 25 | 27 | 32 | 18 | - | - | 29 |

| Amprenavir | 12 | 32 | 21 | 27 | −1 | - | - | 21 |

| Clotrimazole | 6 | −2 | −10 | −10 | 10 | - | - | −44 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Floerl, S.; Kuehne, A.; Hagos, Y. Insights into Transport Function of the Murine Organic Anion-Transporting Polypeptide OATP1B2 by Comparison with Its Rat and Human Orthologues. Toxics 2026, 14, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010010

Floerl S, Kuehne A, Hagos Y. Insights into Transport Function of the Murine Organic Anion-Transporting Polypeptide OATP1B2 by Comparison with Its Rat and Human Orthologues. Toxics. 2026; 14(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010010

Chicago/Turabian StyleFloerl, Saskia, Annett Kuehne, and Yohannes Hagos. 2026. "Insights into Transport Function of the Murine Organic Anion-Transporting Polypeptide OATP1B2 by Comparison with Its Rat and Human Orthologues" Toxics 14, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010010

APA StyleFloerl, S., Kuehne, A., & Hagos, Y. (2026). Insights into Transport Function of the Murine Organic Anion-Transporting Polypeptide OATP1B2 by Comparison with Its Rat and Human Orthologues. Toxics, 14(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010010