Corn-Based Fermented Beverages: Nutritional Value, Microbial Dynamics, and Functional Potential—An Overview

Abstract

1. Introduction

| Morphology | References | |

|---|---|---|

| Dent | On the periphery and rear of the grainm there is a hard, dense, translucent endosperm, while the central part is soft, white, and floury. These grains have indentations. | [17] |

| Flint | They have a hard, thick, and glassy endosperm, and are smooth and round grains. | [17] |

| Waxy | Their main characteristic is that they contain 100% amylopectin, which gives them a sticky texture and various uses. | [18] |

| Sweet | This type is notable mainly for its high sugar content (5–6%) and low starch content (10–11%). | [19,20] |

| Pop | Small, hard, round corn kernels that have the ability to accumulate pressure and pop to form popcorn. | [21,22] |

| Floury | It is mainly composed of soft starch with a small amount of vitreous material. | [17] |

| Pigmentation | ||

| White | It is usually the most widely used in food, animal feed, and industry, as consumers prefer it. | [23] |

| Yellow/Red/Orange | Characterized by its high carotenoid content. | [24] |

| Blue/Purple/Black | This type of corn stands out for its high content of antioxidant compounds such as polyphenols and anthocyanins. | [25,26] |

| Application | ||

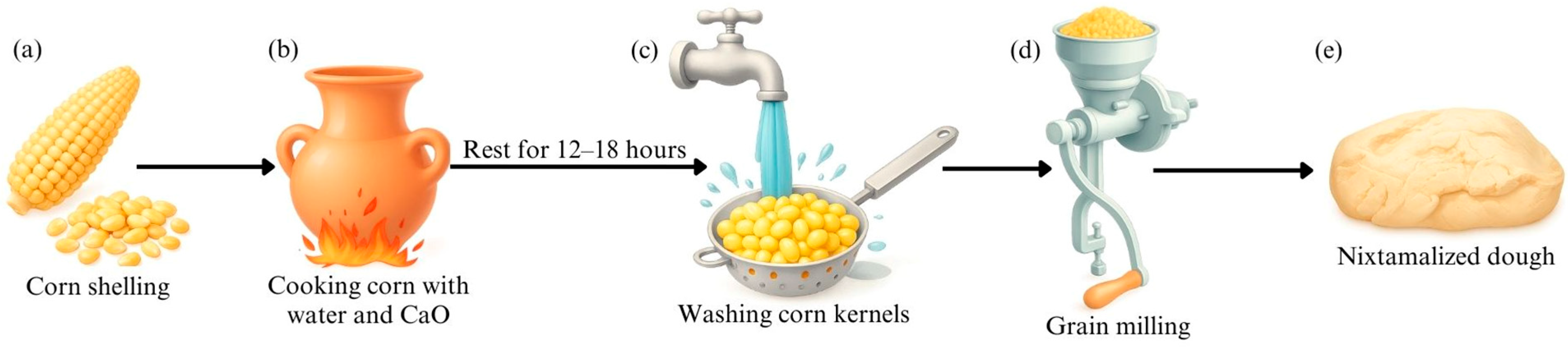

| Food-Grade | These are ideal for dry milling and nixtamalization. | [27] |

| Animal feed (Silage) | Intended for animal consumption, with fewer restrictions than that intended for human consumption. | [28] |

| Specialty | This is produced and used for very specific purposes, usually obtained through genetic selection and crossbreeding. | [29] |

| Genetics | ||

| Natives | Those that have been preserved by farmers through seed selection. | [30] |

| Hybrids | Conventional crossbreeding of seeds with different genetic material. | [31] |

| Transgenic | Produced through the genetic insertion of a specific gene into the corn genome. | [32] |

2. Nutritional Composition of Different Corn Varieties Based on Their Pigmentation

2.1. Carbohydrates

2.1.1. Starch

2.1.2. Fiber

2.2. Proteins

2.3. Fats

2.4. Ash (Minerals)

3. Bioactive Compounds in Different Corn Varieties

3.1. Phenolic Compounds and Anthocyanins

3.2. Carotenoids

4. Fermented Beverage Production in Latin America Based on Different Corn Varieties

4.1. Pozol

4.2. Atole Agrio

4.3. Tejuino

4.4. Beers

4.4.1. Chicha

4.4.2. Sendecho

5. Fermentation Effects in Corn and Development of Microorganisms

5.1. Microorganisms in Fermented Beverages Based on Different Varieties of Corn

5.1.1. Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB)

5.1.2. Yeast and Fungi

5.1.3. Pathogenic Microorganisms

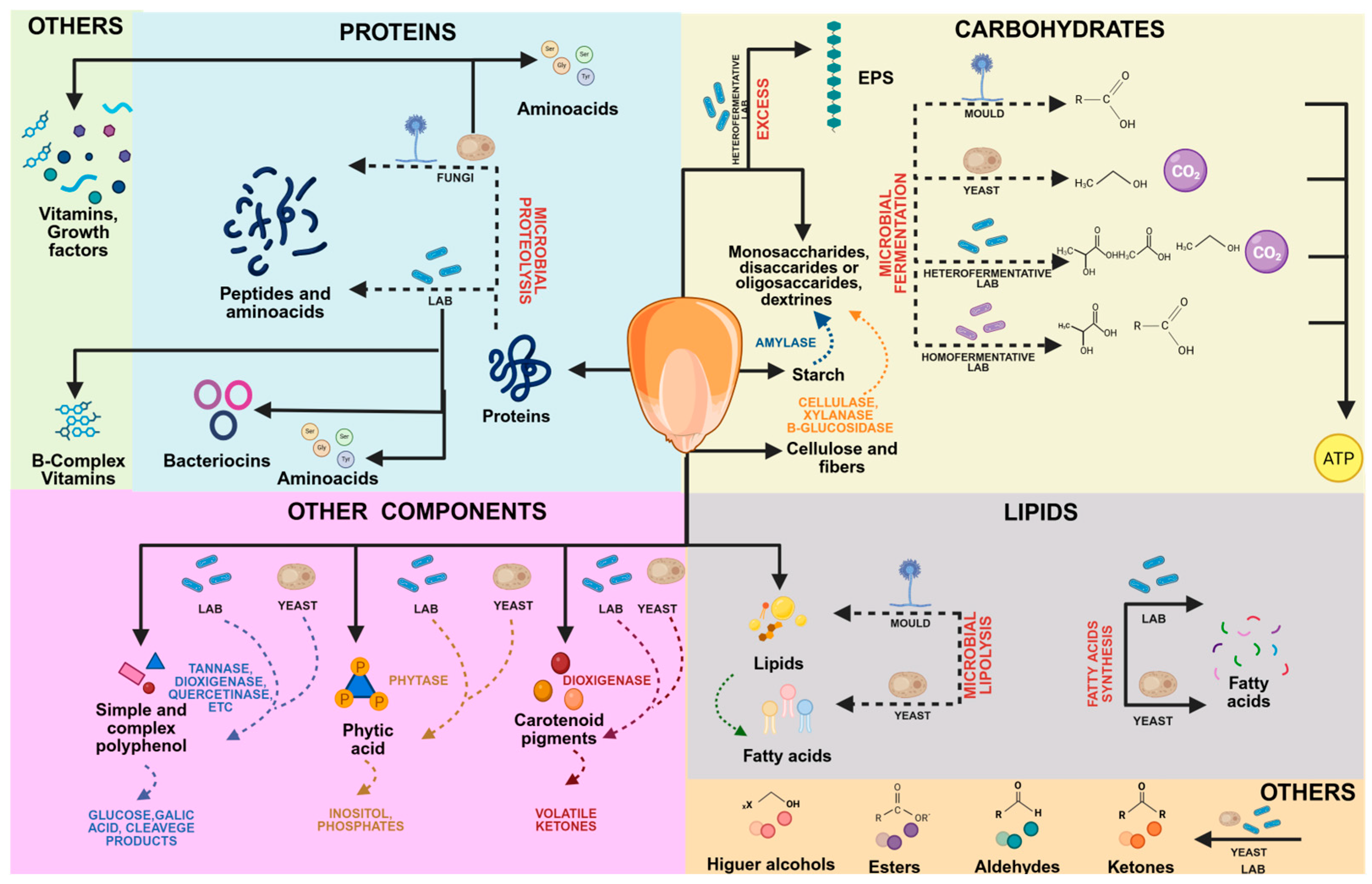

6. Nutrients Biotransformation and Production of Value-Added Compounds

6.1. Impact on Carbohydrate

6.2. Impact on Protein

6.3. Impact on Lipids

6.4. Impact on Phytochemicals

6.5. Microbial Metabolite Production During Fermentation

6.6. Antinutritional Molecules Reduction

7. Final Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carrasco-Vargas, W.; Montero-Flores, P.; Cobos-Mora, F.; Gómez-Villalva, J. Historia Del Maíz Desde Tiempos Ancestrales Hasta La Actualidad. J. Sci. Res. 2023, 8, 115–130. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas, R.D. El Maíz, Fuente de Cultura Mesoamericana. Rev. Museol. Kóot 2021, 12, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fideicomisos Instituidos en Relación con la Agricultura. Panorama Agroalimentario—Maíz 2024; Fideicomisos Instituidos en Relación con la Agricultura: Morelia, Mexico, 2024.

- Goodman, M.M.; Bird, R.M.K. The Races of Maize Iv: Tentative Grouping of 219 Latin American Races. Econ. Bot. 1977, 31, 204–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracco, M. Caracterización Genética del Germoplasma de Razas de Maíz Autóctonas Provenientes del Noreste Argentino; Universidad de Buenos Aires: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Comision Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad Razas de Maíz de México|Biodiversidad Mexicana. Available online: https://www.biodiversidad.gob.mx/diversidad/alimentos/maices/razas-de-maiz (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Rosado-Ortega, A.; Villasante-Serrano, B.A.; Hernández-Salcido, G. Los Herederos del Maíz; Ramírez Hernández, C., Ed.; Instituto Nacional de los Pueblos Indígenas (INPI): Mexico City, México, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves-López, C.; Rossi, C.; Maggio, F.; Paparella, A.; Serio, A. Changes Occurring in Spontaneous Maize Fermentation: An Overview. Fermentation 2020, 6, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.J.; Brouwer-Brolsma, E.M.; Burton-Pimentel, K.J.; Vergères, G.; Feskens, E.J.M. A Systematic Review to Identify Biomarkers of Intake for Fermented Food Products. Genes. Nutr. 2021, 16, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelan, K.; Jones, N. Fermented Foods: Availability, Cost, Ingredients, Nutritional Content and On-pack Claims. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2022, 35, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, S.A.; Erol, Z.; Rugji, J.; Taşçı, F.; Kahraman, H.A.; Toppi, V.; Musa, L.; Di Giacinto, G.; Bahmid, N.A.; Mehdizadeh, M. An Overview of Fermentation in the Food Industry-Looking Back from a New Perspective. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2023, 10, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreu, M.; Coutado-Saavedra, R. The Role of Ferments in Food Sustainability. Nutr. Hosp. 2022, 39, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secretaria de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural. Bebidas Mexicanas Con Maíz. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/agricultura/es/articulos/bebidas-mexicanas-con-maiz?idiom=es (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Dimidi, E.; Cox, S.R.; Rossi, M.; Whelan, K. Fermented Foods: Definitions and Characteristics, Impact on the Gut Microbiota and Effects on Gastrointestinal Health and Disease. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros-Guamán, D.H.; Cusco-Morocho, K.T. Importancia Cultural Gastronómica de la Chicha de Maíz y su Contribución en la Identidad Gastronómica de la Provincia de Manabí; Universidad de Cuenca: Cuenca, Ecuador, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Blandino, A.; Al-Aseeri, M.E.; Pandiella, S.S.; Cantero, D.; Webb, C. Cereal-Based Foods and Beverages. Food. Res. Int. 2003, 35, 527–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darrah, L.L.; McMullen, M.D.; Zuber, M.S. Breeding, Genetics and Seed Corn Production. In Corn: Chemistry and Technology, 3rd ed.; Serna-Saldivar, S.O., Ed.; AACC International Press: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2019; pp. 19–41. ISBN 9780128119716. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, J.; Du, Y.; Yu, Y.; Yan, Y.; Luan, X.; Liu, S.; Shen, Q.; Chen, H.; Tang, J.; Wang, G. Genetic Control of Cereal Kernel Texture: Towards a Maize Model. Crop J. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TRACY, W.F. Sweet Corn: Zea mays L. In Genetic Improvement of Vegetable Crops; Kalloo, G., Bergh, B.O., Eds.; Pergamon: Oxford, UK, 1993; pp. 777–807. ISBN 978-0-08-040826-2. [Google Scholar]

- Swapna, G.; Jadesha, G.; Mahadevu, P. Sweet Corn-A Future Healthy Human Nutrition Food. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2020, 9, 3859–3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherchel, V.Y.; Kuprichenkov, D.S. Comparative Characteristics of Two Methods for Popping Popcorn. Grain Crops 2023, 7, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sosa-Morales, M.E.; Andaluz-Mejía, L.M.; Cardona-Herrera, R.; Castañeda-Rodríguez, L.R.; Ochoa-Montes, D.A.; Santiesteban-López, N.A.; Rojas-Laguna, R. Quality Evaluation of Yellow Corn (Zea mays Cv. Everta) Subjected to 27.12-MHz Radio Frequency Treatments for Popcorn Production. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 57, 3263–3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranum, P.; Peña-Rosas, J.P.; Garcia-Casal, M.N. Global Maize Production, Utilization, and Consumption. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2014, 1312, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capocchi, A.; Bottega, S.; Spanò, C.; Fontanini, D. Phytochemicals and Antioxidant Capacity in Four Italian Traditional Maize (Zea mays L.) Varieties. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 68, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y.; Lee, K.Y.; Kim, M.; Hong, M.; Deepa, P.; Kim, S. A Review of the Biological Properties of Purple Corn (Zea mays L.). Sci. Pharm. 2023, 91, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lao, F.; Sigurdson, G.T.; Giusti, M.M. Health Benefits of Purple Corn (Zea mays L.) Phenolic Compounds. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2017, 16, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooney, L.W.; Serna-Saldivar, S.O. Food-Grade Corn Quality for Lime-Cooked Tortillas and Snacks. In Tortillas: Wheat Flour and Corn Products; Rooney, L.W., Serna-Saldivar, S.O., Eds.; AACC International Press: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2015; pp. 227–246. ISBN 9780128123683. [Google Scholar]

- Karnatam, K.S.; Mythri, B.; Un Nisa, W.; Sharma, H.; Meena, T.K.; Rana, P.; Vikal, Y.; Gowda, M.; Dhillon, B.S.; Sandhu, S. Silage Maize as a Potent Candidate for Sustainable Animal Husbandry Development—Perspectives and Strategies for Genetic Enhancement. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1150132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, P.; Pratt, R.C.; Hoffman, N.; Montgomery, R. Specialty Corns. In Corn: Chemistry and Technology, 3rd ed.; Serna-Saldivar, S.O., Ed.; AACC International Press: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2019; pp. 289–303. ISBN 9780128119716. [Google Scholar]

- Secretaria de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural. Maíces Nativos, Patrimonio Biológico, Agrícola, Cultural y Económico|Secretaría de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural|Gobierno|Gob.Mx. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/agricultura/articulos/un-apoyo-para-agricultores-de-maices-nativos (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Troyer, A.F. Handbook of Maize. In Handbook of Maize: Genetics and Genomics; Bennetzen, J.L., Hake, S., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 87–114. ISBN 978-0-387-77863-1. [Google Scholar]

- Marina, B.; Mena, L.; Reyes, J.; Cárdenas, A. Maíz Transgénico: ¿Beneficio Para Quién? Estud. Soc. (Hermosillo Son.) 2015, 23, 141–161. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Q.; Li, J.; Li, H.; Zhou, D.; Wang, X.; Tian, Y.; Qin, J.; Tian, X.; Lu, Q. The Effects of Purple Corn Pigment on Growth Performance, Blood Biochemical Indices, Meat Quality, Muscle Amino Acids, and Fatty Acids of Growing Chickens. Foods 2022, 11, 1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.Z.; Lu, Q.; Paengkoum, P.; Paengkoum, S. Effect of Purple Corn Pigment on Change of Anthocyanin Composition and Unsaturated Fatty Acids during Milk Storage. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 7808–7812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Pavón, D.; Soto-Sigala, K.S.; Cano-Sampedro, E.; Méndez-Trujillo, V.; Navarro-Ibarra, M.J.; Pérez-Pasten-Borja, R.; Olvera-Sandoval, C.; Torres-Maravilla, E. Pigmented Native Maize: Unlocking the Potential of Anthocyanins and Bioactive Compounds from Traditional to Functional Beverages. Beverages 2024, 10, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yang, P.; Zhao, J. Ferulic Acid Mediates Prebiotic Responses of Cereal-Derived Arabinoxylans on Host Health. Anim. Nutr. 2022, 9, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Nuño, Y.A.; Zermeño-Ruiz, M.; Vázquez-Paulino, O.D.; Nuño, K.; Villarruel-López, A. Bioactive Compounds from Pigmented Corn (Zea mays L.) and Their Effect on Health. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kljak, K.; Grbeša, D. Carotenoid Content and Antioxidant Activity of Hexane Extracts from Selected Croatian Corn Hybrids. Food Chem. 2015, 167, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trono, D. Carotenoids in Cereal Food Crops: Composition and Retention Throughout Grain Storage and Food Processing. Plants 2019, 8, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization. Nutritional Value of Maize. In Maize in Human Nutrition; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 1993; ISBN 92-5-103013-8. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía Censo Agropecuario (CA) 2022. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ca/2022/ (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Abiose, S.H.; Ikujenlola, A.V. Comparison of Chemical Composition, Functional Properties and Amino Acids Composition of Quality Protein Maize and Common Maize (Zea may L). Afr. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 5, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouf Shah, T.; Prasad, K.; Kumar, P. Maize—A Potential Source of Human Nutrition and Health: A Review. Cogent Food Agric. 2016, 2, 1166995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Fonseca, A. Comparación de AQP Entre Maíz Criollo y Maíz Blanco Comercial; Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana: Mexico City, Mexico, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Majamanda, J.; Katundu, M.; Ndolo, V.; Tembo, D. A Comparative Study of Physicochemical Attributes of Pigmented Landrace Maize Varieties. J. Food Qual. 2022, 2022, 6294336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libron, J.A.M.A.; Cardona, D.E.M.; Mateo, J.M.C.; Beltran, A.K.M.; Tuaño, A.P.P.; Laude, T.P. Nutritional Properties and Phenolic Acid Profile of Selected Philippine Pigmented Maize with High Antioxidant Activity. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2021, 101, 103954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mex-Álvarez, R.M.J.; Garma-Quen, P.M.; Bolívar-Fernández, N.J.; Guillén-Morales, M.M. Proximal and Phytochemical Analysis of Five Maize Varieties from Campeche, Mexico. Rev. Latinoam. Recur. Nat. 2016, 12, 74–80. [Google Scholar]

- Agama-Acevedo, E.; Juárez-García, E.; Evangelista-Lozano, S.; Rosales-Reynoso, O.L.; Bello-Pérez, L.A. Characteristics of Maize Starch and Relatioship with Is Biosynthesis Enzymes. Agrociencia 2013, 47, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Copeland, L.; Blazek, J.; Salman, H.; Tang, M.C. Form and Functionality of Starch. Food Hydrocoll. 2009, 23, 1527–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello-Perez, L.A.; Flores-Silva, P.C.; Agama-Acevedo, E.; Tovar, J. Starch Digestibility: Past, Present, and Future. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2020, 100, 5009–5016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agama-Acevedo, E.; Ottenhof, M.A.; Farhat, I.M.; Paredes-López, O.; Ortíz-Cereceres, J.; Bello-Pérez, L.A. Efecto de La Nixtamalización Sobre Las Características Moleculares Del Almidón de Variedades Pigmentadas de Maíz. Interciencia 2004, 29, 643–649. [Google Scholar]

- Agama-Acevedo, E.; De La Rosa, A.P.B.; Méndez-Montealvo, G.; Bello-Pérez, L.A. Physicochemical and Biochemical Characterization of Starch Granules Isolated of Pigmented Maize Hybrids. Starch/Staerke 2008, 60, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmi, S.; Goudar, G.; Singh, M.; Dhaliwal, H.S.; Sharma, P.; Longvah, T. Variability in Resistant Starch, Vitamins, Carotenoids, Phytochemicals and in-Vitro Antioxidant Properties among Diverse Pigmented Grains. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2021, 15, 2774–2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, B.A.; Pacheco, M.T. Chemical Modification of Yellow and Purple Corn Starch: Effect on Its Resistance to in Vitro Digestion. Rev. Cienc. Tecnol. 2025, 18, 92–99. [Google Scholar]

- Villaroel, P.; Gómez, C.; Vera, C.; Torres, J. Resistant Starch: Technological Characteristics and Physiological Interests. Rev. Chil. Nutr. 2018, 45, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, N. Análisis de Fibra Dietética. In Producción y Manejo de Datos de Composicion Química de Alimentos en Nutrición; Morón, C., Zacarías, I., de Pablo, S., Eds.; Food and Agriculture Organization: Santiago, Chile, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, N.D.; Lupton, J.R. Dietary Fiber. Adv. Nutr. 2011, 2, 151–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello-Pérez, L.A.; Camelo-Mendez, G.A.; Agama-Acevedo, E.; Utilla-Coello, R.G. Nutraceutic Aspects of Pigmented Maize: Digestibility of Carbohydrates and Anthocyanins. Agrociencia 2016, 50, 1041–1063. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Salinas, P.A.; Zavala-García, F.; Urías-Orona, V.; Muy-Rangel, D.; Heredia, J.B.; Niño-Medina, G. Chromatic, Nutritional and Nutraceutical Properties of Pigmented Native Maize (Zea mays L.) Genotypes from the Northeast of Mexico. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2020, 45, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çetin-Babaoğlu, H.; Yalım, N.; Kale, E.; Tontul, S.A. Pigmented Whole Maize Grains for Functional Value Added and Low Glycemic Index Snack Production. Food Biosci. 2021, 44, 101349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camelo-Méndez, G.A.; Agama-Acevedo, E.; Tovar, J.; Bello-Pérez, L.A. Functional Study of Raw and Cooked Blue Maize Flour: Starch Digestibility, Total Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Activity. J. Cereal Sci. 2017, 76, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somavat, P. Evaluation and Modification of Processing Techniques for Recovery of Anthocyanins from Colored Corn. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bello-Pérez, L.A.; Flores-Silva, P.C.; Camelo-Méndez, G.A.; Paredes-López, O.; De Figueroa-Cárdenas, J.D. Effect of the Nixtamalization Process on the Dietary Fiber Content, Starch Digestibility, and Antioxidant Capacity of Blue Maize Tortilla. Cereal Chem. 2015, 92, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uriarte-Aceves, P.M.; Cuevas-Rodríguez, E.O.; Gutiérrez-Dorado, R.; Mora-Rochín, S.; Reyes-Moreno, C.; Puangpraphant, S.; Milan-Carrillo, J. Physical, Compositional, and Wet-Milling Characteristics of Mexican Blue Maize (Zea mays L.) Landrace. Cereal Chem. 2015, 92, 491–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, R.; Cheryan, M. Zein: The Industrial Protein from Corn. Ind. Crops Prod. 2001, 13, 171–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles-Plata, V.T.; Serna Saldivar, S.; de Dios Figueroa-Cárdenas, J.; Rooney, W.L.; Dávila-Vega, J.P.; Chuck-Hernández, C.; Escalante-Aburto, A. Biophysical, Nutraceutical, and Technofunctional Features of Specialty Cereals: Pigmented Popcorn and Sorghum. Foods 2023, 12, 2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansilla, P.S.; Nazar, M.C.; Pérez, G.T. Flour Functional Properties of Purple Maize (Zea mays L.) from Argentina. Influence of Environmental Growing Conditions. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 146, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özdemir, E.; Cengiz, R.; Sade, B. Characterization of White, Yellow, Red, and Purple Colored Corns (Zea mays indentata L.) According to Bio—Active Compounds and Quality Traits. Anadolu Tarım Bilim. Derg. 2023, 38, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, S.; Singh, N.; Kaur, A. Characteristics of Normal and Waxy Corn: Physicochemical, Protein Secondary Structure, Dough Rheology and Chapatti Making Properties. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 3285–3296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broa Rojas, E.; Vázquez Carrillo, M.G.; Estrella Chulím, N.G.; Hernández Salgado, J.H.; Ramírez Valverde, B.; Bahena Delgado, G. Physicochemical Characteristics and Quality of the Protein of Pigmented Native Maize from Morelos in Two Years of Cultivation. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agric. 2019, 10, 683–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan-Chan, M.; Moguel-Ordóñez, Y.; Gallegos-Tintoré, S.; Chel-Guerrero, L.; Betancur-Ancona, D. Chemical and Nutritional Characterization of High Quality Protein Maize (Zea mays L.) Varieties Developed in Yucatan, México. Biotecnia 2021, 23, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera-Arellano, D.; Badan-Ribeiro, A.P.; Serna-Saldivar, S.O. Corn Oil: Composition, Processing, and Utilization. In Corn: Chemistry and Technology, 3rd ed.; Serna-Saldivar, S.O., Ed.; AACC International Press: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2019; pp. 593–613. ISBN 9780128119716. [Google Scholar]

- Peña-Betancourt, S.D.; Gutiérrez-Tolentino, R.; Schettino, B. Proximate Composition, Fatty Acid Profile and Mycotoxin Contamination in Several Varieties of Mexican Maize. Food Nutr. Sci. 2017, 8, 865–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Saturated Fatty Acid and Trans-Fatty Acid Intake for Adults and Children: WHO Guideline; World Health Organization (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Total Fat Intake for the Prevention of Unhealthy Weight Gain in Adults and Children: WHO Guideline Summary; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lunn, J.; Theobald, H.E. The Health Effects of Dietary Unsaturated Fatty Acids. Nutr. Bull. 2006, 31, 178–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelan, J.; Fritsche, K. Linoleic Acid. Adv. Nutr. 2013, 4, 311–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jandacek, R.J. Linoleic Acid: A Nutritional Quandary. Healthcare 2017, 5, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Xin, Q.; Yuan, R.; Miao, Y.; Yang, M.; Mo, H.; Chen, K.; Cong, W. Protective Effects of Oleic Acid and Polyphenols in Extra Virgin Olive Oil on Cardiovascular Diseases. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2024, 13, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomer, X.; Pizarro-Delgado, J.; Barroso, E.; Vázquez-Carrera, M. Palmitic and Oleic Acid: The Yin and Yang of Fatty Acids in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 29, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santa-María, C.; López-Enríquez, S.; Montserrat-de la Paz, S.; Geniz, I.; Reyes-Quiroz, M.E.; Moreno, M.; Palomares, F.; Sobrino, F.; Alba, G. Update on Anti-Inflammatory Molecular Mechanisms Induced by Oleic Acid. Nutrients 2023, 15, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preciado-Ortiz, R.E.; García-Lara, S.; Ortiz-Islas, S.; Ortega-Corona, A.; Serna-Saldivar, S.O. Response of Recurrent Selection on Yield, Kernel Oil Content and Fatty Acid Composition of Subtropical Maize Populations. Field Crops Res. 2013, 142, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-Maldonado, S.H.; Vázquez-Carrillo, M.G.; Aguirre-Gómez, J.A.; Serrano-Fujarte, I. Fatty Acid, Phenolic Compounds and Industrial Quality of Native Maize Landraces from Guanajuato. Rev. Fitotec. Mex. 2015, 38, 213–222. [Google Scholar]

- Mutlu, C.; Arslan-Tontul, S.; Candal, C.; Kilic, O.; Erbas, M. Physicochemical, Thermal, and Sensory Properties of Blue Corn (Zea mays L.). J. Food Sci. 2018, 83, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pliego, C.E.; Ramírez, M.D.L.; Ortiz, R.; Hidalgo, B. Caracterización de Proteínas, Grasa y Perfil Graso de Maíces Criollos (Zea mays) En Poblados Del Estado de México. Soc. Rural. Prod. Medio Ambiente 2021, 21, 156–169. [Google Scholar]

- Latham, M.C. Cereals, Starchy Roots and Other Mainly Carbohydrate Foods. In Human Nutrition in the Developing World; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 1997; ISBN 92-5-303818-7. [Google Scholar]

- Batal, A.B.; Dale, N.M.; Saha, U.K. Mineral Composition of Corn and Soybean Meal. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2010, 19, 361–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador-Reyes, R.; Rebellato, A.P.; Lima Pallone, J.A.; Ferrari, R.A.; Clerici, M.T.P.S. Kernel Characterization and Starch Morphology in Five Varieties of Peruvian Andean Maize. Food Res. Int. 2021, 140, 110044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Rosa, L.A.; Moreno-Escamilla, J.O.; Rodrigo-García, J.; Alvarez-Parrilla, E. Phenolic Compounds. In Postharvest Physiology and Biochemistry of Fruits and Vegetables; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 253–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, T.C.; Giusti, M.M. Anthocyanins. Adv. Nutr. 2015, 6, 620–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Grijalva, E.P.; Ambriz-Pére, D.L.; Leyva-López, N.; Castillo-López, R.I.; Heredia, J.B. Review: Dietary Phenolic Compounds, Health Benefits and Bioaccessibility. Arch. Latinoam. Nutr. 2016, 66, 87–100. [Google Scholar]

- Zilic, S.; Milasinovic, M.; Terzic, D.; Barac, M.; Ignjatovic-Micic, D. Grain Characteristics and Composition of Maize Specialty Hybrids. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2011, 9, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trehan, S.; Singh, N.; Kaur, A. Characteristics of White, Yellow, Purple Corn Accessions: Phenolic Profile, Textural, Rheological Properties and Muffin Making Potential. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 2334–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smorowska, A.J.; Żołnierczyk, A.K.; Nawirska-Olszańska, A.; Sowiński, J.; Szumny, A. Nutritional Properties and In Vitro Antidiabetic Activities of Blue and Yellow Corn Extracts: A Comparative Study. J. Food Qual. 2021, 2021, 8813613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriano, S.; Balconi, C.; Valoti, P.; Redaelli, R. Comparison of Total Polyphenols, Profile Anthocyanins, Color Analysis, Carotenoids and Tocols in Pigmented Maize. LWT 2021, 144, 111257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Lagunas, L.L.; Cruz-Gracida, M.; Barriada-Bernal, L.G.; Rodríguez-Méndez, L.I. Profile of Phenolic Acids, Antioxidant Activity and Total Phenolic Compounds during Blue Corn Tortilla Processing and Its Bioaccessibility. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, 4688–4696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas-Moreno, Y.; Santillán-Fernández, A.; de la Torre, I.A.; Ramírez-Díaz, J.L.; Ledesma-Miramontes, A.; Martínez-Ortiz, M.Á. Physical Traits and Phenolic Compound Diversity in Maize Accessions with Blue-Purple Grain (Zea mays L.) of Mexican Races. Agriculture 2024, 14, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urias-Peraldí, M.; Gutiérrez-Uribe, J.A.; Preciado-Ortiz, R.E.; Cruz-Morales, A.S.; Serna-Saldívar, S.O.; García-Lara, S. Nutraceutical Profiles of Improved Blue Maize (Zea mays) Hybrids for Subtropical Regions. Field Crops Res. 2013, 141, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas Montilla, E.; Hillebrand, S.; Antezana, A.; Winterhalter, P. Soluble and Bound Phenolic Compounds in Different Bolivian Purple Corn (Zea mays L.) Cultivars. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 7068–7074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bani, C.; Di Lorenzo, C.; Restani, P.; Mercogliano, F.; Colombo, F. Phenolic Profile and In Vitro Antioxidant Activity of Different Corn and Rice Varieties. Plants 2023, 12, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, J.; Zorrilla-López, U.; Farré, G.; Zhu, C.; Sandmann, G.; Twyman, R.M.; Capell, T.; Christou, P. Nutritionally Important Carotenoids as Consumer Products. Phytochem. Rev. 2015, 14, 727–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saenz, E.; Borrás, L.; Gerde, J.A. Carotenoid Profiles in Maize Genotypes with Contrasting Kernel Hardness. J. Cereal Sci. 2021, 99, 103206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida-Rios, S.; Dias-Paes, M.C.; Cardoso, W.S.; Bórem, A.; Teixeira, F. Color of Corn Grains and Carotenoid Profile of Importance for Human Health. Am. J. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 857–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Li, D.; He, M.; Chen, J.; Liu, C. Comparison of Carotenoid Composition in Immature and Mature Grains of Corn (Zea mays L.) Varieties. Int. J. Food Prop. 2016, 19, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kljak, K.; Duvnjak, M.; Bedeković, D.; Kiš, G.; Janječić, Z.; Grbeša, D. Commercial Corn Hybrids as a Single Source of Dietary Carotenoids: Effect on Egg Yolk Carotenoid Profile and Pigmentation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Armendáriz, B.; Cardoso-Ugarte, G.A. Traditional Fermented Beverages in Mexico: Biotechnological, Nutritional, and Functional Approaches. Food Res. Int. 2020, 136, 109307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pswarayi, F.; Loponen, J.; Sibakov, J. Sourdough and Cereal Beverages. In Handbook on Sourdough Biotechnology, 2nd ed.; Gobbetti, M., Ganzle, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 351–371. ISBN 978-3-031-23084-4. [Google Scholar]

- Rizo, J.; Rogel, M.A.; Guillén, D.; Wacher, C.; Martinez-Romero, E.; Encarnación, S.; Sánchez, S.; Rodríguez-Sanoja, R. Nitrogen Fixation in Pozol, a Traditional Fermented Beverage. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 86, e00588-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secretaria de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural. Pozol, Una Bebida Comestible. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/agricultura/articulos/pozol-una-bebida-comestible (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Wacher, C.; Cañas, A.; Bárzana, E.; Lappe, P.; Ulloa, M.; Owens, J.D. Microbiology of Indian and Mestizo Pozol Fermentations. Food Microbiol. 2000, 17, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Escobar, A.E. Desarrollo y Caracterización Física Química y Nutracéutica de Un Pozol Elaborado Con Maíz (Zea mays L.) Criollo (Azul y Rojo), Adicionado Con Cacao (Theobroma cacao). Master’s Thesis, Universidad Autónoma de Querétaro, Querétaro, Mexico, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Robles, L.D.C. Actividad Antimicrobiana en la Fermentación Natural del Pozol Blanco Con Pimienta (Pimenta dioica L.) Merril); Universidad Juárez Autónoma de Tabasco: Tabasco, Mexico, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Patra, M.; Bashir, O.; Amin, T.; Wani, A.W.; Shams, R.; Chaudhary, K.S.; Mirza, A.A.; Manzoor, S. A Comprehensive Review on Functional Beverages from Cereal Grains-Characterization of Nutraceutical Potential, Processing Technologies and Product Types. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez Vera, R.; González Cortés, N.; Contreras, A.M.; Corona Cruz, A. Evaluación Microbiológica y Sensorial de Fermentados de Pozol Blanco, Con Cacao (Theobroma cacao) y Coco (Cocos nucifera). Rev. Venez. Cienc. Tecnol. Aliment. 2010, 1, 70–80. [Google Scholar]

- Jenatton, M.; Morales, H. Civilized Cola and Peasant Pozol: Young People’s Social Representations of a Traditional Maize Beverage and Soft Drinks within Food Systems of Chiapas, Mexico. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 44, 1052–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez Cortes, M.S.; Verdugo Valdez, A.G.; Lopez Zuñiga, E.J.; Vela Gutierrez, G. El Atole Agrio: Su Presencia y Modo de Preparación en la Cultura Alimentaria de Chiapas. In El Maíz: Conocimiento de su Patrimonio Gastronómico y Cultural; Rateike, L.A., Pola, G.P., Eds.; UNICACH: Mexico City, Mexico, 2019; pp. 87–94. [Google Scholar]

- Väkeväinen, K.; Hernández, J.; Simontaival, A.I.; Severiano-Pérez, P.; Díaz-Ruiz, G.; von Wright, A.; Wacher-Rodarte, C.; Plumed-Ferrer, C. Effect of Different Starter Cultures on the Sensory Properties and Microbiological Quality of Atole Agrio, a Fermented Maize Product. Food Control 2020, 109, 106907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverría Falla, J. Caracterización de Las Bebidas Tradicionales de Guatemala a Base de Cereales y Su Mejoramiento En Calidad Nutricional. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad del Valle de Guatemala, Guatemala City, Guatemala, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Manzo-Fuentes, M.I. Cuantificación de Antioxidantes En Bebidas de Maíz (Zea mays). Master’s Thesis, Universidad de Ciencias y Artes de Chiapas, Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Mexico, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Aparicio Martínez, C. Evaluación de Variedades Pigmentadas de Maíz Para La Producción de Atole. Master’s Thesis, Instituto de Enseñanza e Investigación en Ciencias Agrícolas, Turrialba, Costa Rica, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Mora, D. Valor Social, Económico y Nutracéutico de Los Maíces Nativos Pigmentados En Localidades de Puebla y Tlaxcala, Su Rescate y Revalorización. Master’s Thesis, Institución de Enseñanza e Investigación en Ciencias Agrícolas, Puebla, Mexico, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cabezas Elizondo, D.A. El Tejuino, El Bate y La Tuba Bebidas Refrescantes: Símbolos Que Perduran de Generación En Generación En El Estado de Colima. Razón Palabra 2016, 20, 89–104. [Google Scholar]

- Ulloa, M.; Henera, T.; Taboada, J. Saccharomyces cerevisiae y Saccharomyces uvarum Aislados de Diferentes Muestras de Tesgüino de Jalisco, México. Sci. Fungorum 1977, 11, 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio-Castillo, Á.E.; Santiago-López, L.; Vallejo-Cordoba, B.; Hernández-Mendoza, A.; Sáyago-Ayerdi, S.G.; González-Córdova, A.F. Traditional Non-Distilled Fermented Beverages from Mexico to Based on Maize: An Approach to Tejuino Beverage. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2021, 23, 100283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas-Guevara, M.D.L.; Mendoza-Gamiño, H.; Espitia-Orozco, F.J.; Villar, I.N.R.-D. Comparación Sensorial de Una Bebida Fermentada de Maíz (Tejuino) y Una Bebida Fermentada de Sorgo Rojo. Investig. Desarro. Cienc. Tecnol. Aliment. 2023, 8, 387–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Uscanga, B.R.; González-Quezada, E.; Solis-Pacheco, J.R.; Aguilar-Uscanga, B.R.; González-Quezada, E.; Solis-Pacheco, J.R. Traditional Fermented Beverages in México. In The Science of Fermentation; Chavarri Hueda, M., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2024; ISBN 978-0-85014-499-4. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Guzmán, K.N.; Torres-León, C.; Martinez-Medina, G.A.; De La Rosa, O.; Hernández-Almanza, A.; Alvarez-Perez, O.B.; Araujo, R.; González, L.R.; Londoño, L.; Ventura, J.; et al. Traditional Fermented Beverages in Mexico. In Fermented Beverages: Volume 5. The Science of Beverages; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 605–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robledo-Márquez, K.; Ramírez, V.; González-Córdova, A.F.; Ramírez-Rodríguez, Y.; García-Ortega, L.; Trujillo, J. Research Opportunities: Traditional Fermented Beverages in Mexico. Cultural, Microbiological, Chemical, and Functional Aspects. Food Res. Int. 2021, 147, 110482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Castillo, Á.E.; Méndez-Romero, J.I.; Reyes-Díaz, R.; Santiago-López, L.; Vallejo-Cordoba, B.; Hernández-Mendoza, A.; Sáyago-Ayerdi, S.G.; González-Córdova, A.F. Tejuino, a Traditional Fermented Beverage: Composition, Safety Quality, and Microbial Identification. Foods 2021, 10, 2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, J. La Chichera y El Patrón: Chicha and the Energetics of Feasting in the Prehistoric Andes. Archaeol. Pap. Am. Anthropol. Assoc. 2004, 14, 241–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezo-Torres, M.N. Análisis de La Variabilidad de Las Características Bioactivas Durante El Proceso Fermentativo de La Chicha Guiñapo, Bebida Tradicional de La Ciudad de Arequipa Obtenida En Condiciones Controladas. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Católica de Santa María, Arequipa, Peru, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Meléndez, J.; Malpartida, O.; Chasquibol, N.A. Technological Development of an Instant Product Based on Fermented Purple Corn (Zea mays L.) Beverage. Biol. Life Sci. Forum 2024, 37, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Yana, D.; Aguilar-Morón, B.; Pezo-Torres, N.; Shetty, K.; Gálvez Ranilla, L. Ancestral Peruvian Ethnic Fermented Beverage “Chicha” Based on Purple Corn (Zea mays L.): Unraveling the Health-Relevant Functional Benefits. J. Ethn. Foods 2020, 7, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piló, F.B.; Carvajal-Barriga, E.J.; Guamán-Burneo, M.C.; Portero-Barahona, P.; Dias, A.M.M.; de Freitas, L.F.D.; Gomes, F.; de Cássia Oliveira Gomes, F.; Rosa, C.A. Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Populations and Other Yeasts Associated with Indigenous Beers (Chicha) of Ecuador. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2018, 49, 808–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez Mendoza, M. Análisis Del Patrimonio Gastronómico Entre Los Mazahuas de San Antonio Pueblo Nuevo, San José Del Rincón, México. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México, Estado de México, México, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Domínguez, M.D.R.; Rojo-Burgos, M.; Ventura-Secundido, M.; Solórzano-Benítez, A. Estandarización de La Producción de Una Bebida Tradicional a Base de Maíz (Sende). Rev. Sist. Exp. 2017, 4, 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Marcial Medina, B.; Marín-Togo, M.C.; González Pablo, L. Importance of the Mazahua Milpa in the Northwest of the State of Mexico: Perspective on Land Use Change. Cienc. Ergo-Sum 2024, 31, e224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Medina, A.; Estarrón-Espinosa, M.; Verde-Calvo, J.R.; Lelièvre-Desmas, M.; Escalona-Buendía, H.B. Pigmented Corn for Brewing Purpose: From Grains to Malt, a Study of Volatile Composition. J. Food Process Preserv. 2021, 45, e16057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Medina, A.; Estarrón-Espinosa, M.; Verde-Calvo, J.R.; Lelièvre-Desmas, M.; Escalona-Buendiá, H.B. Renewing Traditions: A Sensory and Chemical Characterisation of Mexican Pigmented Corn Beers. Foods 2020, 9, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Medina, A. Brewing with Pigmented Corn Malt: Chemical, Sensory Properties, and Consumer’s Expectations. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, Ciudad de México, México, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Sarmiento, W.; Peña-Ocaña, B.A.; Lam-Gutiérrez, A.; Guzmán-Albores, J.M.; Jasso-Chávez, R.; Ruíz-Valdiviezo, V.M. Microbial Community Structure, Physicochemical Characteristics and Predictive Functionalities of the Mexican Tepache Fermented Beverage. Microbiol. Res. 2022, 260, 127045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalante, A.; Wacher, C.; Farrés, A. Lactic Acid Bacterial Diversity in the Traditional Mexican Fermented Dough Pozol as Determined by 16S RDNA Sequence Analysis. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2001, 64, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejo-García, L.C.; Espíritu-García, A.; Miranda-Molina, A.; López-Munguía, A. Characterization of Oligosaccharides Produced by a Truncated Dextransucrase from Weissella Confusa Wcp3a Isolated from Pozol, a Traditional Fermented Corn Beverage. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 298, 139891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, J.; König, S.; Hutzler, M.; Kunz, O.; Krogerus, K.; Lehnhardt, F.; Magalhães, F.; Svedlund, N.; Grijalva-Vallejos, N.; Gibson, B. Genetic Pre-Adaptations in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Andean Chicha Isolates Facilitate Industrial Brewery Application. Food Microbiol. 2025, 132, 104815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebaza-Cárdenas, T.; Montes-Villanueva, N.D.; Fernández, M.; Delgado, S.; Ruas-Madiedo, P. Microbiological and Physical-Chemical Characteristics of the Peruvian Fermented Beverage “Chicha de Siete Semillas”: Towards the Selection of Strains with Acidifying Properties. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2023, 406, 110353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas, C.; Barkla, B.J.; Wacher, C.; Delgado-Olivares, L.; Rodríguez-Sanoja, R. Protein Extraction Method for the Proteomic Study of a Mexican Traditional Fermented Starchy Food. J. Proteom. 2014, 111, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Hernández, M.; Rodríguez-Alegría, M.E.; López-Munguía, A.; Wacher, C. Evaluation of Xylan as Carbon Source for Weissella spp., a Predominant Strain in Pozol Fermentation. LWT 2018, 89, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Albores, J.A.; Arámbula-Villa, G.; Preciado-Ortíz, R.E.; Moreno-Martínez, E. Aflatoxins in Pozol, a Nixtamalized, Maize-Based Food. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2004, 94, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainz, T.; Pérez, J.; Villaseca, J.; Hernández, U.; Eslava, C.; Mendoza, G.; Wacher, C. Survival to Different Acid Challenges and Outer Membrane Protein Profiles of Pathogenic Escherichia coli Strains Isolated from Pozol, a Mexican Typical Maize Fermented Food. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2005, 105, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elizaquível, P.; Pérez-Cataluña, A.; Yépez, A.; Aristimuño, C.; Jiménez, E.; Cocconcelli, P.S.; Vignolo, G.; Aznar, R. Pyrosequencing vs. Culture-Dependent Approaches to Analyze Lactic Acid Bacteria Associated to Chicha, a Traditional Maize-Based Fermented Beverage from Northwestern Argentina. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2015, 198, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashida, F.M. Ancient Beer and Modern Brewers: Ethnoarchaeological Observations of Chicha Production in Two Regions of the North Coast of Peru. J. Anthr. Archaeol. 2008, 27, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejo, J.A.; Miranda, P.; Flores-Félix, J.D.; Sánchez-Juanes, F.; Ageitos, J.M.; González-Buitrago, J.M.; Velázquez, E.; Villa, T.G. Atypical Yeasts Identified as Saccharomyces Cerevisiae by MALDI-TOF MS and Gene Sequencing Are the Main Responsible of Fermentation of Chicha, a Traditional Beverage from Peru. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2013, 36, 560–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yépez, A.; Luz, C.; Meca, G.; Vignolo, G.; Mañes, J.; Aznar, R. Biopreservation Potential of Lactic Acid Bacteria from Andean Fermented Food of Vegetal Origin. Food Control 2017, 78, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Cadena, Y.; Restrepo-Escobar, N.; Valencia-García, F. Microbiological and Physicochemical Characterization of a Traditionally Fermented Corn Product: “Champús”. Vitae 2023, 30, a349215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio-Cadavid, E.; Chaves-López, C.; Tofalo, R.; Paparella, A.; Suzzi, G. Detection and Identification of Wild Yeasts in Champús, a Fermented Colombian Maize Beverage. Food Microbiol. 2008, 25, 771–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios-Roblero, C.; Rosas-Quijano, R.; Salvador-Figueroa, M.; Gálvez-López, D.; Vázquez-Ovando, A. Antifungal Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Fermented Beverages with Activity against Colletotrichum Gloeosporioides. Food Biosci. 2019, 29, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Ramírez, L.L.; Rodríguez-Sanoja, R.; Tecante, A.; García-Garibay, M.; Sainz, T.; Wacher, C. Tolerance to Acid and Alkali by Streptococcus infantarius subsp. infantarius Strain 25124 Isolated from Fermented Nixtamal Dough: Pozol. Studies in APT Broth. Food Microbiol. 2020, 90, 103458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, M.S.; Ramos, C.L.; González-Avila, M.; Gschaedler, A.; Arrizon, J.; Schwan, R.F.; Dias, D.R. Probiotic Properties of Weissella cibaria and Leuconostoc citreum Isolated from Tejuino—A Typical Mexican Beverage. LWT 2017, 86, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Väkeväinen, K.; Valderrama, A.; Espinosa, J.; Centurión, D.; Rizo, J.; Reyes-Duarte, D.; Díaz-Ruiz, G.; von Wright, A.; Elizaquível, P.; Esquivel, K.; et al. Characterization of Lactic Acid Bacteria Recovered from Atole Agrio, a Traditional Mexican Fermented Beverage. LWT 2018, 88, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Maravilla, E.; Méndez-Trujillo, V.; Hernández-Delgado, N.C.; Bermúdez-Humarán, L.G.; Reyes-Pavón, D. Looking inside Mexican Traditional Food as Sources of Synbiotics for Developing Novel Functional Products. Fermentation 2022, 8, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves-López, C.; Cordero-Bueso, G. Microbial Diversity and Safety in Fermented Beverages. Beverages 2022, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyer, L.C.; Zannini, E.; Arendt, E.K. Lactic Acid Bacteria as Sensory Biomodulators for Fermented Cereal-Based Beverages. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 54, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar-Ramírez, M.C.; Jaimez-Ordaz, J.; Escorza-Iglesias, V.A.; Rodríguez-Serrano, G.M.; Contreras-López, E.; Ramírez-Godínez, J.; Castañeda-Ovando, A.; Morales-Estrada, A.I.; Felix-Reyes, N.; González-Olivares, L.G. Lactobacillus Pentosus ABHEAU-05: An in Vitro Digestion Resistant Lactic Acid Bacterium Isolated from a Traditional Fermented Mexican Beverage. Rev. Argent. Microbiol. 2020, 52, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampe, F.; Miambi, E. Cluster Analysis, Richness and Biodiversity Indexes Derived from Denaturing Gradient Gel Electrophoresis Fingerprints of Bacterial Communities Demonstrate That Traditional Maize Fermentations Are Driven by the Transformation Process. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2000, 60, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Sánchez, R.; Hernández-Oaxaca, D.; Escobar-Zepeda, A.; Cerrillo, B.R.; López-Munguía, A.; Segovia, L. Analysing the Dynamics of the Bacterial Community in Pozol, a Mexican Fermented Corn Dough. Microbiology 2023, 169, 001355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Castillo, Á.E.; Zamora-Gasga, V.M.; Sánchez-Burgos, J.A.; Ruiz-Valdiviezo, V.M.; Montalvo-González, E.; Velázquez-Estrada, R.M.; González-Córdova, A.F.; Sáyago-Ayerdi, S.G. Gut Metabolites Produced during in Vitro Colonic Fermentation of the Indigestible Fraction of a Maize-Based Traditional Mexican Fermented Beverage, Tejuino. Food Chem. Mol. Sci. 2022, 5, 100150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, P.I.K.; Tuaño, A.P.P.; Juanico, C.B. Microbial Quality, Safety, Sensory Acceptability, and Proximate Composition of a Fermented Nixtamalized Maize (Zea mays L.) Beverage. J. Cereal Sci. 2022, 107, 103521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fentie, E.G.; Lim, K.; Andargie, Y.E.; Azizoglu, U.; Shin, J.H. Globalizing the Health-Promoting Potential of Fermented Foods: A Culturomics Pathway to Probiotics. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 163, 105119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, C.M.; Andrus, C.F.T.; Ida, J.; Richardson, N. Local Water Source Variation and Experimental Chicha de Maíz Brewing: Implications for Interpreting Human Hydroxyapatite Δ18O Values in the Andes. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2015, 4, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, L.M.; Neef, A.; Vignolo, G.; Belloch, C. Yeast Diversity during the Fermentation of Andean Chicha: A Comparison of High-Throughput Sequencing and Culture-Dependent Approaches. Food Microbiol. 2017, 67, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sainz, T.; Wacher, C.; Espinoza, J.; Centurión, D.; Navarro, A.; Molina, J.; Inzunza, A.; Cravioto, A.; Eslava, C. Survival and Characterization of Escherichia Coli Strains in a Typical Mexican Acid-Fermented Food. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2001, 71, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, T.; Machireddy, J.; Vuppu, S. Comprehensive Study on Hygiene and Quality Assessment Practices in the Production of Drinkable Dairy-Based and Plant-Based Fermented Products. Fermentation 2024, 10, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byakika, S.; Mukisa, I.M.; Byaruhanga, Y.B.; Male, D.; Muyanja, C. Influence of Food Safety Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices of Processors on Microbiological Quality of Commercially Produced Traditional Fermented Cereal Beverages, a Case of Obushera in Kampala. Food Control 2019, 100, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasek, O.; Barteczko, J.; Barć, J.; Micek, P. Nutrient Content of Different Wheat and Maize Varieties and Their Impact on Metabolizable Energy Content and Nitrogen Utilization by Broilers. Animals 2020, 10, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, C.; Wu, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhuang, H. Effects of Fermentation Modification and Combined Modification with Heat-Moisture Treatment on the Multiscale Structure, Physical and Chemical Properties of Corn Flour and the Quality of Traditional Fermented Corn Noodles. Foods 2024, 13, 4043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masehlele, D.P.; Adeyinka Adebo, J.; Olamide Kewuyemi, Y.; Ayodeji Adebo, O. Development of a Maize Meal Based-Drink Fermented Using Kefir Grains or Yoghurt Starter Cultures (Lactobacillus bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus). Agric. Eng. Int. CIGR J. 2023, 25, 212. [Google Scholar]

- Decimo, M.; Quattrini, M.; Ricci, G.; Fortina, M.G.; Brasca, M.; Silvetti, T.; Manini, F.; Erba, D.; Criscuoli, F.; Casiraghi, M.C. Evaluation of Microbial Consortia and Chemical Changes in Spontaneous Maize Bran Fermentation. AMB Express 2017, 7, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gänzle, M.G. Lactic Metabolism Revisited: Metabolism of Lactic Acid Bacteria in Food Fermentations and Food Spoilage. Curr Opin. Food Sci. 2015, 2, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gänzle, M.G.; Vermeulen, N.; Vogel, R.F. Carbohydrate, Peptide and Lipid Metabolism of Lactic Acid Bacteria in Sourdough. Food Microbiol. 2007, 24, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaunmüller, T.; Eichert, M.; Richter, H.; Unden, G. Variations in the Energy Metabolism of Biotechnologically Relevant Heterofermentative Lactic Acid Bacteria during Growth on Sugars and Organic Acids. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2006, 72, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cázares-Vásquez, M.L.; Rodríguez-Herrera, R.; Aguilar-González, C.N.; Sáenz-Galindo, A.; Solanilla-Duque, J.F.; Contreras-Esquivel, J.C.; Flores-Gallegos, A.C. Microbial Exopolysaccharides in Traditional Mexican Fermented Beverages. Fermentation 2021, 7, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripari, V. Techno-Functional Role of Exopolysaccharides in Cereal-Based, Yogurt-Like Beverages. Beverages 2019, 5, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosu-Tudor, S.-S.; Stefan, I.-R.; Stancu, M.-M.; Cornea, C.-P.; De Vuyst, L.; Zamfir, M. Microbial and Nutritional Characteristics of Fermented Wheat Bran in Traditional Romanian Borş Production. Rom. Biotechnol. Lett. 2019, 24, 440–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banwo, K.; Jimoh, O.; Olojede, A.; Ogundiran, T. Functional Properties and Antioxidant Potentials of Kunun-Zaki (A Non-Alcoholic Millet Beverage) Produced Using Pediococcus pentosaceus and Pichia kudriavzevii. Food Biotechnol. 2024, 38, 159–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heperkan, D.; Daskaya-Dikmen, C.; Bayram, B. Evaluation of Lactic Acid Bacterial Strains of Boza for Their Exopolysaccharide and Enzyme Production as a Potential Adjunct Culture. Process Biochem. 2014, 49, 1587–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maicas, S. The Role of Yeasts in Fermentation Processes. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, J.; Jiang, X.; Song, P.; Yang, Q.; Sun, M.; Dong, Z.; Lu, Y.; Dou, S.; Dong, L. Multi-Omics Insights into Microbial Interactions and Fermented Food Quality. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, L. Impact of Sourdough Fermentation on Nutrient Transformations in Cereal-Based Foods: Mechanisms, Practical Applications, and Health Implications. Grain Oil Sci. Technol. 2024, 7, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basso, T.O.; Gomes, F.S.; Lopes, M.L.; de Amorim, H.V.; Eggleston, G.; Basso, L.C. Homo-and Heterofermentative Lacto-bacilli Differently Affect Sugarcane-Based Fuel Ethanol Fermentation. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2014, 105, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, S.W.; Chong, A.Q.; Chin, N.L.; Talib, R.A.; Basha, R.K. Sourdough Microbiome Comparison and Benefits. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nenciarini, S.; Reis-Costa, A.; Pallecchi, M.; Renzi, S.; D’Alessandro, A.; Gori, A.; Cerasuolo, B.; Meriggi, N.; Bartolucci, G.L.; Cavalieri, D. Investigating Yeast–Lactobacilli Interactions through Co-Culture Growth and Metabolite Analysis. Fermentation 2023, 9, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruzzi, L.; Rosaria Corbo, M.; Sinigaglia, M.; Bevilacqua, A. Brewer’s Yeast in Controlled and Uncontrolled Fermentations, with a Focus on Novel, Nonconventional, and Superior Strains. Food Rev. Int. 2016, 32, 341–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galimberti, A.; Bruno, A.; Agostinetto, G.; Casiraghi, M.; Guzzetti, L.; Labra, M. Fermented Food Products in the Era of Globalization: Tradition Meets Biotechnology Innovations. Cur.r Opin. Biotechnol. 2021, 70, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaemene, D.I.; Fadupin, G.T. Effect of Fermentation, Germination and Combined Germination-Fermentation Processing Methods on the Nutrient and Anti-Nutrient Contents of Quality Protein Maize (QPM) Seeds. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manag. 2020, 24, 1625–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogodo, A.C.; Ugbogu, O.; Onyeagba, R.A.; Okereke, H.C. Effect of Lactic Acid Bacteria Consortium Fermentation on the Proximate Composition and in-Vitro Starch/Protein Digestibility of Maize (Zea mays) Flour. Am. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 4, 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Ongol, M.P.; Eugène, N.; Vasanthakaalam, H.; Patrick Ongol, M.; Niyonzima, E.; Gisanura, I. Effect of Germination and Fermentation on Nutrients in Maize Flour. Pak. J. Food Sci. 2013, 23, 183–188. [Google Scholar]

- Venegas-Ortega, M.G.; Flores-Gallegos, A.C.; Martínez-Hernández, J.L.; Aguilar, C.N.; Nevárez-Moorillón, G.V. Production of Bioactive Peptides from Lactic Acid Bacteria: A Sustainable Approach for Healthier Foods. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2019, 18, 1039–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Morales, M.; Wacher-Rodarte, M.D.C.; Hernández-Sánchez, H. Preliminary Studies on Chorote—A Traditional Mexican Fermented Product. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2005, 21, 293–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayta, M.; Alpaslan, M.; Köse, E. The Effect of Fermentation on Viscosity and Protein Solubility of Boza, a Traditional Cereal-Based Fermented Turkish Beverage. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2001, 213, 335–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Medina, G.A.; Carranza-Méndez, R.; Amaya-Chantaca, D.P.; Ilyna, A.; Gaviria-Acosta, E.; Hoyos-Concha, J.L.; Chávez-González, M.L.; Govea-Salas, M.; Prado-Barragán, L.A.; Aguilar-González, C.N. Bioactive Peptides from Food Industrial Wastes. In Bioactive Peptides; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 169–203. [Google Scholar]

- Olakunle, D.T.; Holzapfel, W.H.; Odunfa, S.A. Selection, Use and the Influence of Starter Cultures in the Nutrition and Processing Improvement of Ogi. J. Food Sci. Nutr. Res. 2023, 6, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Li, D.J.; Liu, C.Q. Effect of Fermentation on the Nutritive Value of Maize. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 47, 755–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizo, J.; Guillén, D.; Díaz-Ruiz, G.; Wacher, C.; Encarnación, S.; Sánchez, S.; Rodríguez-Sanoja, R. Metaproteomic Insights Into the Microbial Community in Pozol. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 714814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebo, J.A.; Njobeh, P.B.; Gbashi, S.; Oyedeji, A.B.; Ogundele, O.M.; Oyeyinka, S.A.; Adebo, O.A. Fermentation of Cereals and Legumes: Impact on Nutritional Constituents and Nutrient Bioavailability. Fermentation 2022, 8, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.S.; Elozeiri, A.A. Metabolic Processes During Seed Germination. In Advances in Seed Biology; InTech: Hyogo, Japan, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Terefe, Z.K.; Omwamba, M.N.; Nduko, J.M. Effect of Solid State Fermentation on Proximate Composition, Antinutritional Factors and in Vitro Protein Digestibility of Maize Flour. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 9, 6343–6352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelule, P.K.; Mbongwa, H.P.; Carries, S.; Gqaleni, N. Lactic Acid Fermentation Improves the Quality of Amahewu, a Traditional South African Maize-Based Porridge. Food Chem. 2010, 122, 656–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhang, J.; Li, L.; Gu, T.; Chen, S.; Wang, J.; Gao, M. The Release of Bound Phenolics to Enhance the Antioxidant Activity of Cornmeal by Liquid Fermentation with Bacillus subtilis. Foods 2025, 14, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acosta-Estrada, B.A.; Gutiérrez-Uribe, J.A.; Serna-Saldívar, S.O. Bound Phenolics in Foods, a Review. Food Chem. 2014, 152, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebo, O.A.; Medina-Meza, I.G. Impact of Fermentation on the Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of Whole Cereal Grains: A Mini Review. Molecules 2020, 25, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez-González, M.; Rodríguez-Durán, L.V.; Balagurusamy, N.; Prado-Barragán, A.; Rodríguez, R.; Contreras, J.C.; Aguilar, C.N. Biotechnological Advances and Challenges of Tannase: An Overview. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2012, 5, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, N.; Esteban-Torres, M.; Mancheño, J.M.; De las Rivas, B.; Muñoza, R. Tannin Degradation by a Novel Tannase Enzyme Present in Some Lactobacillus plantarum Strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 2991–2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valencia-Hernández, L.J.; Wong-Paz, J.E.; Ascacio-Valdés, J.A.; Prado-Barragan, A.; Chávez-González, M.L.; Aguilar, C.N. Fungal Biodegradation of Procyanidin in Submerged Fermentation. Fermentation 2025, 11, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Fang, Z. Impact of Fermentation on the Structure and Antioxidant Activity of Selective Phenolic Compounds. Food Biosci. 2023, 56, 103147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulajová, A.; Matejčeková, Z.; Kohajdová, Z.; Mošovská, S.; Hybenová, E.; Valík, Ľ. Changes in Phenolic Composition, Antioxidant, Sensory and Microbiological Properties during Fermentation and Storage of Maize Products. Food Prod. Process. Nutr. 2024, 6, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Ndolo, V.; Fu, B.X.; Ames, N.; Katundu, M.; Beta, T. Effect of Processing on Bioaccessibility of Carotenoids from Orange Maize Products. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 56, 3299–3310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uenojo, M.; Pastore, G.M. β-Carotene Biotransformation to Obtain Aroma Compounds. Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 30, 822–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bento-Silva, A.; Duarte, N.; Belo, M.; Mecha, E.; Carbas, B.; Brites, C.; Vaz Patto, M.C.; Bronze, M.R. Shedding Light on the Volatile Composition of Broa, a Traditional Portuguese Maize Bread. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashau, M.E.; Maliwichi, L.L.; Jideani, A.I.O. Non-Alcoholic Fermentation of Maize (Zea mays) in Sub-Saharan Africa. Fermentation 2021, 7, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obatolu, V.A.; Adeniyi, P.O.; Ashaye, O.A. Nutritional, Sensory and Storage Quality of Sekete from Zea mays. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. Eng. 2016, 6, 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- Chawafambira, A.; Nyoni, Q.; Mkungunugwa, T. The Potential of Utilizing Provitamin A-Biofortified Maize in Producing Mutwiwa, a Zimbabwean Traditional Fermented Food. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 9, 1521–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Dai, Z.; Shi, E.; Wan, P.; Chen, G.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Gao, R.; Zeng, X.; Li, D. Study on the Interaction between β-Carotene and Gut Microflora Using an in Vitro Fermentation Model. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2023, 12, 1369–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogundare, O.C.; Odetunde, S.K.; Omotayo, M.A.; Sokefun, O.O.; Akindiya, R.O.; Akinboro, A. Biopreservative Application of Bacteriocins Obtained from Samples Ictalurus punctatus and Fermented Zea mays. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2021, 15, 408–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, H.A.; Tuoheti, T.; Li, Z.; Tekliye, M.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, M. Effect of Novel Bacteriocinogenic Lactobacillus fermentum BZ532 on Microbiological Shelf-Life and Physicochemical and Organoleptic Properties of Fresh Home-Made Bozai. Foods 2021, 10, 2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwuakor, C.E.; Nwaugo, V.O.; Nnadi, C.J.; Emetole, J.M. Effect of Varied Culture Conditions on Crude Supernatant (Bacteriocin) Production from Four Lactobacillus Species Isolated from Locally Fermented Maize (Ogi). Am. J. Microbiol. Res. 2014, 2, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reale, A.; Konietzny, U.; Coppola, R.; Sorrentino, E.; Greiner, R. The Importance of Lactic Acid Bacteria for Phytate Degradation during Cereal Dough Fermentation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 2993–2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Ma, L.; Xuan, Y.; Liang, J. Degradation of Anti-Nutritional Factors in Maize Gluten Feed by Fermentation with Bacillus subtilis: A Focused Study on Optimizing Fermentation Conditions. Fermentation 2024, 10, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kårlund, A.; Paukkonen, I.; Gómez-Gallego, C.; Kolehmainen, M. Intestinal Exposure to Food-Derived Protease Inhibitors: Digestion Physiology-and Gut Health-Related Effects. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adeyemo, S.M.; Onilude, A.A. Enzymatic Reduction of Anti-Nutritional Factors in Fermenting Soybeans by Lactobacillus plantarum Isolates from Fermenting Cereals. Niger. Food J. 2013, 31, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Corn Variety (Zea mays) | Fatty acids (mg/g de TFA) | References | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAA | STA | OLA | LNA | LLA | AAA | ||

| White | 11.00–15.00 | 2.00–4.00 | 33.00–44.00 | 0.50–5.00 | 34.00–52.00 | 0.35–0.55 | [82,83] |

| Yellow | 11.00–13.00 | 2.00–4.00 | 34.00–43.5 | 0.55–4.50 | 37.00–52.00 | 0.35–0.45 | |

| Blue | 2.86 | 4.30 | 52.21 | n.d | 44.85 | n.d | [84] |

| Red | 12.35–13.05 | 2.00–3.45 | 33.5–41.00 | 0.75–0.84 | 42.50–49.70 | n.d | [73,85] |

| Corn Variety (Zea mays) | TPC (mg GAE/100 g DW) | Polyphenols Profile | TAC (mg cy-3-glc equiv/100 g DW) | Anthocyanins Profile | TCC (µg β-carotene/100 g DW) | Carotenoids Profile | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 132.0–273.2 | Ferulic acid, gallic acid, quercetin | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | [43,93] |

| Yellow | 135.9 | Gallic acid, caffeic acid, ferulic acid | n.d | n.d | 675 | Lutein, Zeaxanthin, Cryptoxanthin, α-carotene | [94,95] |

| Blue | 85.6–294.1 | p-coumaric acid, ferulic acids, chlorogenic acid | 181.6–796.2 | Cyanidin 3-glucoside Cyanidin 3-malonyl glucoside Pelargonidin 3-glucoside Peonidin 3-glucoside Pelargonidin 3-malonyl-glucoside | n.d | n.d | [96,97,98] |

| Purple | 311.0–817.6 | p-coumaric acid ferulic acid 8-5′-Ben DiFA | 1.97–71.68 | cyanidin-3-glucoside cyanidin-3-(6″- malonylglucoside) peonidin-3-(6″-malonylglucoside) pelargonidin-3-(dimalonylglucoside) peonidin-3-(dimalonylglucoside) | n.d | n.a | [99] |

| Red | 141–217 | Chlorogenic acid, gallic acid, dihydroxybenzoic acid, syringic acid | n.d | n.d | n.d | n.d | [100] |

| Fermented Beverages | Bacteria | Yeasts | Fungi | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pozol | Lactobacillus plantarum, L. fermentum, L. delbrueckii, Lactococcus lactis, L. casei, Streptococcus suis, Clostridium sp., Acetobacter, Weissella confusa, Bacillus subtilis | Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Candida spp., Geotrichum candidum | Aspergillus | [142,146,147,148,149] |

| Chicha de jora | Lactobacillus, Leuconostoc, Acetobacter | Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Candida ethanolica, Pichia kudriavzevii, Hanseniaspora opuntiae, Wickerhamomyces anomalus | [134,144,145,150,151,152] | |

| Chicha ecuatoriana | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum, Leuconostoc, Weissella | Candida intermedia, Candida parapsilosis, Pichia fermentans, Wickerhamomyces anomalus | [144,152,153] | |

| Champús | Lactobacillus, Weissella, Leuconostoc | Issatchenkia orientalis, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Pichia fermentans, P. kluyveri, Torulospora delbrueckii, Hanseniaspora spp., Zygosaccharomyces fermentati | Galactomyces geotrichum | [154,155] |

| Tejuino | Leuconostoc citreum, Weissella cibaria, Lactobacillus plantarum, L. fermentum, L. paracasei, L. pentosus | Saccharomyces, Candida, Pichia, Wickerhamomyces | [124,129,156,157,158] | |

| Atole agrio | Weissella confusa, Lactobacillus fermentum, Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactococcus lactis, Pediococcus pentosaceus | [117,159] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

López-Reynoso, M.; Martínez-Medina, G.A.; Londoño-Hernández, L.; Aguilar-Zarate, P.; Hernández-Beltrán, J.U.; Hernández-Almanza, A.Y. Corn-Based Fermented Beverages: Nutritional Value, Microbial Dynamics, and Functional Potential—An Overview. Foods 2026, 15, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010027

López-Reynoso M, Martínez-Medina GA, Londoño-Hernández L, Aguilar-Zarate P, Hernández-Beltrán JU, Hernández-Almanza AY. Corn-Based Fermented Beverages: Nutritional Value, Microbial Dynamics, and Functional Potential—An Overview. Foods. 2026; 15(1):27. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010027

Chicago/Turabian StyleLópez-Reynoso, Milagros, Gloria A. Martínez-Medina, Liliana Londoño-Hernández, Pedro Aguilar-Zarate, Javier Ulises Hernández-Beltrán, and Ayerim Y. Hernández-Almanza. 2026. "Corn-Based Fermented Beverages: Nutritional Value, Microbial Dynamics, and Functional Potential—An Overview" Foods 15, no. 1: 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010027

APA StyleLópez-Reynoso, M., Martínez-Medina, G. A., Londoño-Hernández, L., Aguilar-Zarate, P., Hernández-Beltrán, J. U., & Hernández-Almanza, A. Y. (2026). Corn-Based Fermented Beverages: Nutritional Value, Microbial Dynamics, and Functional Potential—An Overview. Foods, 15(1), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010027