Effect of β-Casein Fortification in Milk Protein on Digestion Properties and Release of Bioactive Peptides in a Suckling Rat Pup Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. In Vivo Digestion

2.2.1. Preparation of Milk Protein Solution for Gavage

2.2.2. Grouping and Treatment of Experimental Animals

2.3. Protein Digestion Rate in the Gastrointestinal Tract

2.4. SDS-PAGE Analysis of Gastrointestinal Digesta

2.5. Peptidomic Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

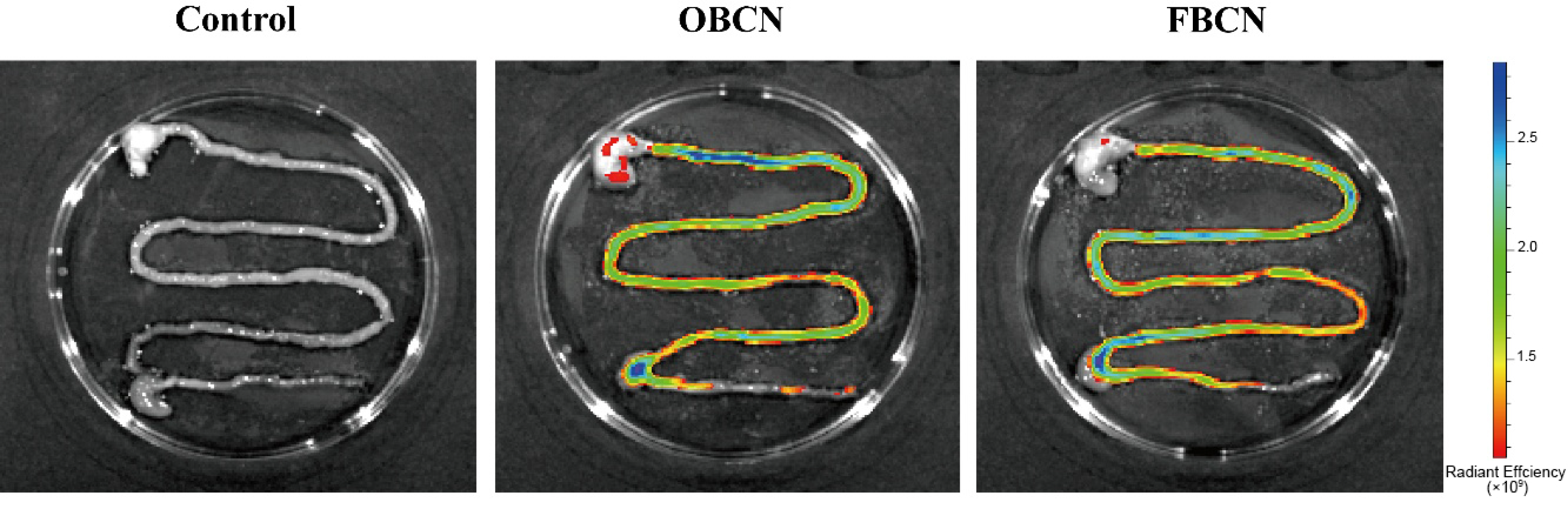

3.1. Digestion Rate of Milk Protein in the Gastrointestinal Tract of Suckling Rat Pups

3.2. In Vivo Digestion of Milk Protein Samples

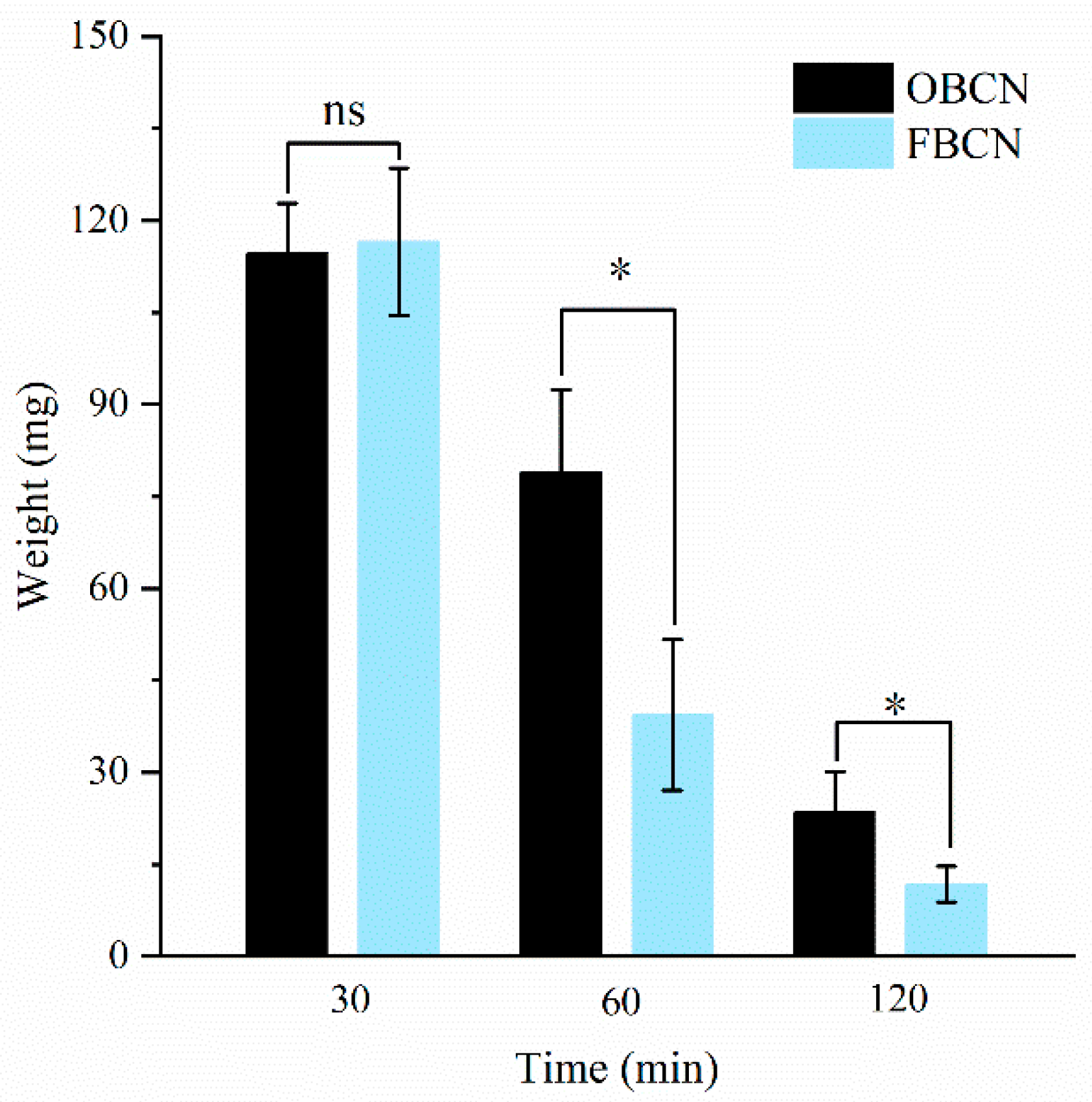

3.2.1. The Weight of Milk Protein Curds in the Stomach of Suckling Rat Pups

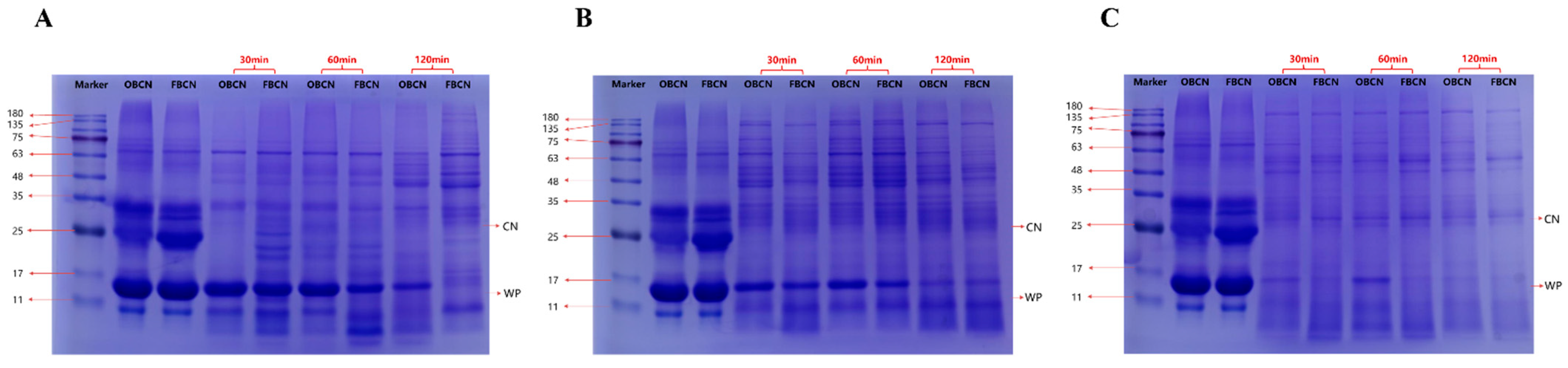

3.2.2. SDS-PAGE of Milk Protein in the Gastrointestinal Digesta of Suckling Rat Pups

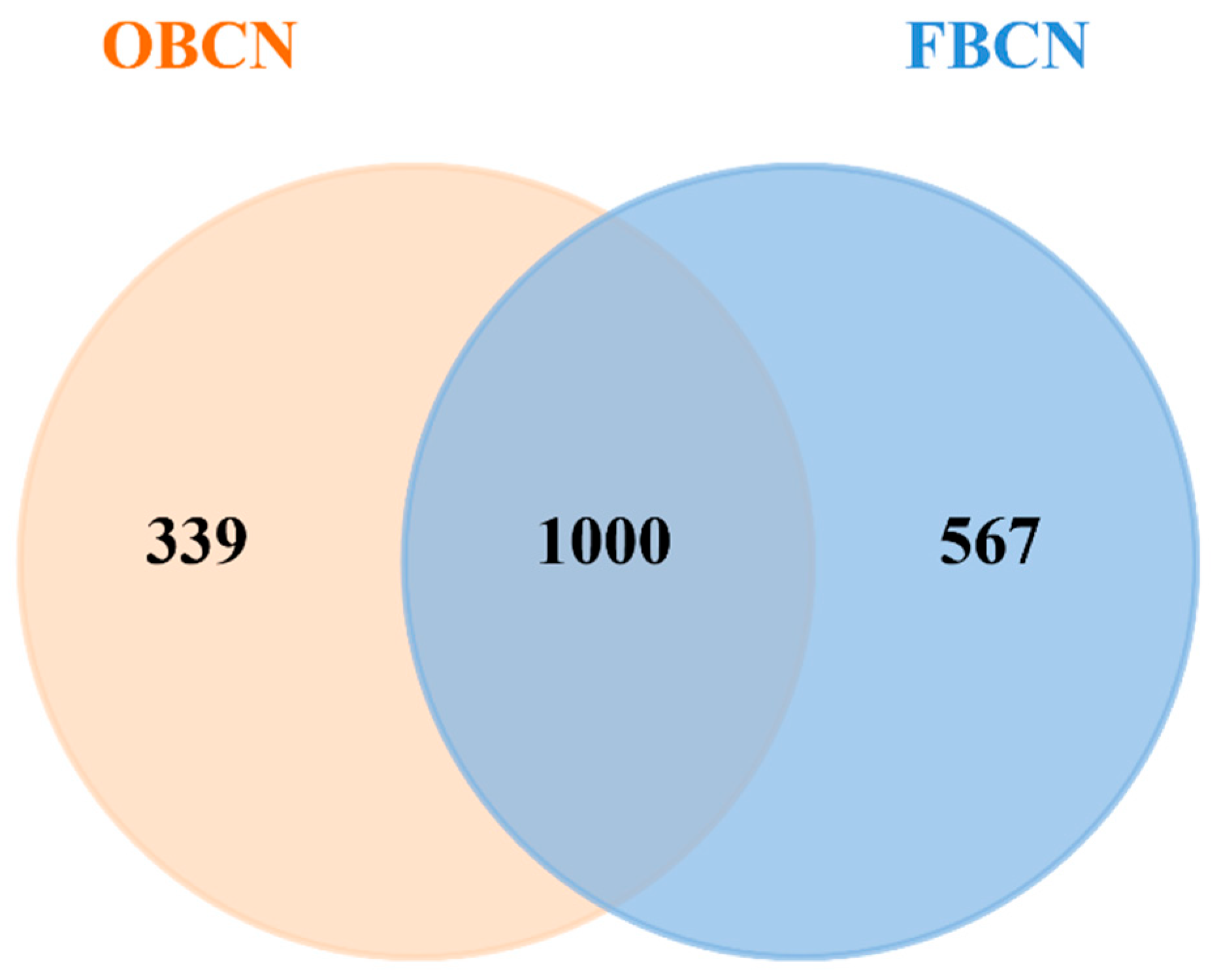

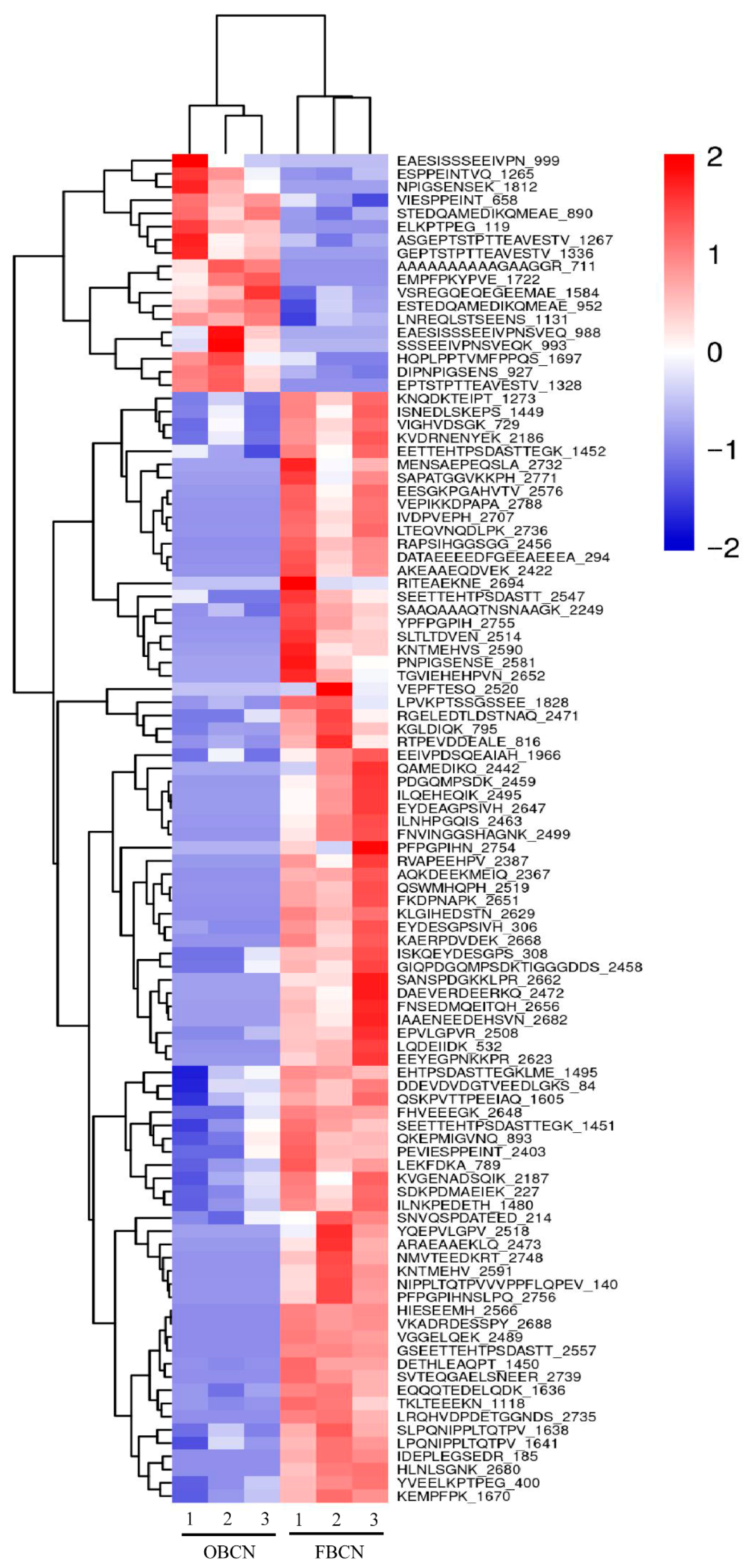

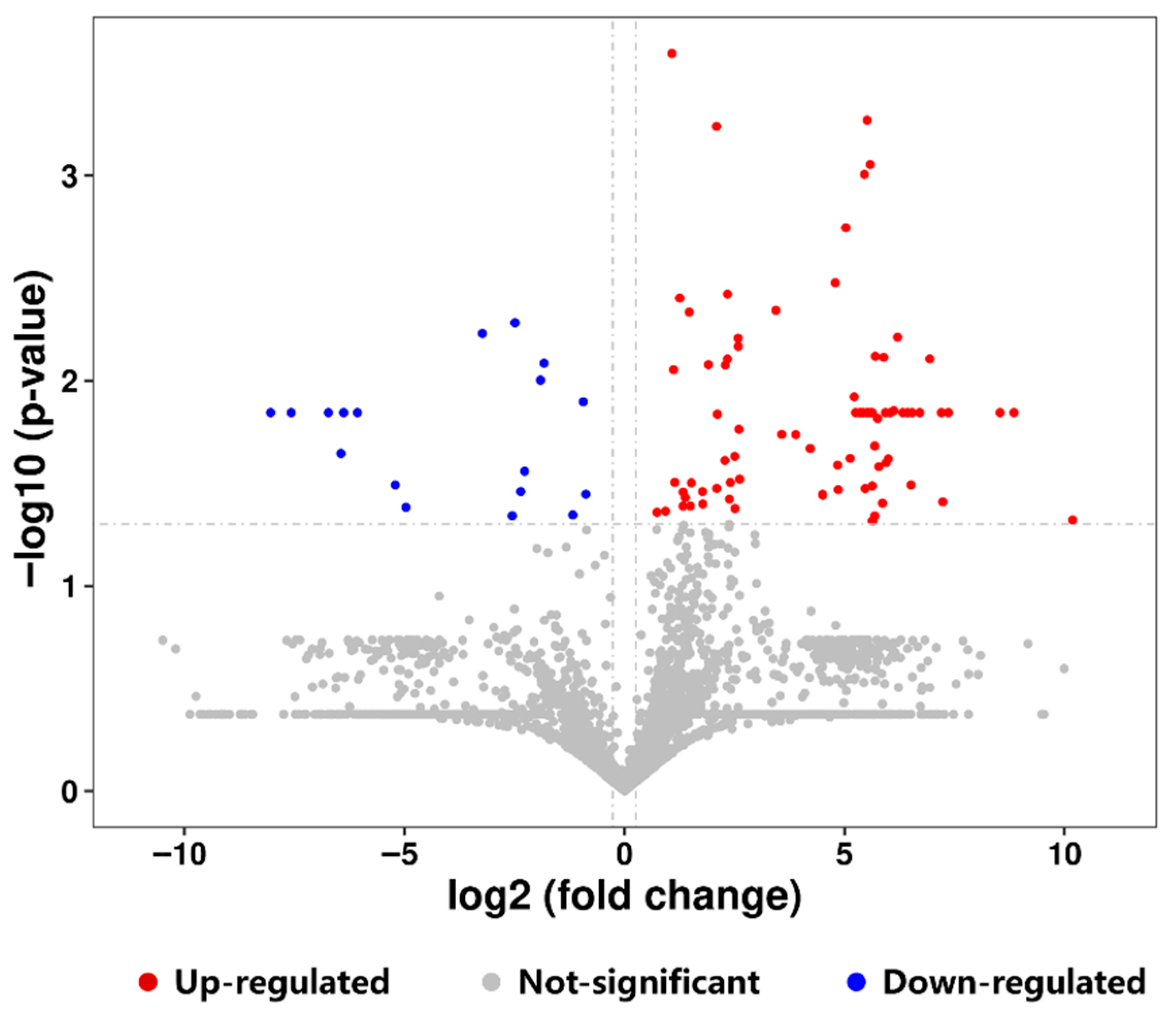

3.3. Peptidomic Analysis of Intestinal Digesta of Suckling Rat Pups

3.3.1. Analysis of Differential Peptide Originated from Milk Protein

3.3.2. Analysis of Potentially Bioactive Peptides Originated from Milk Protein

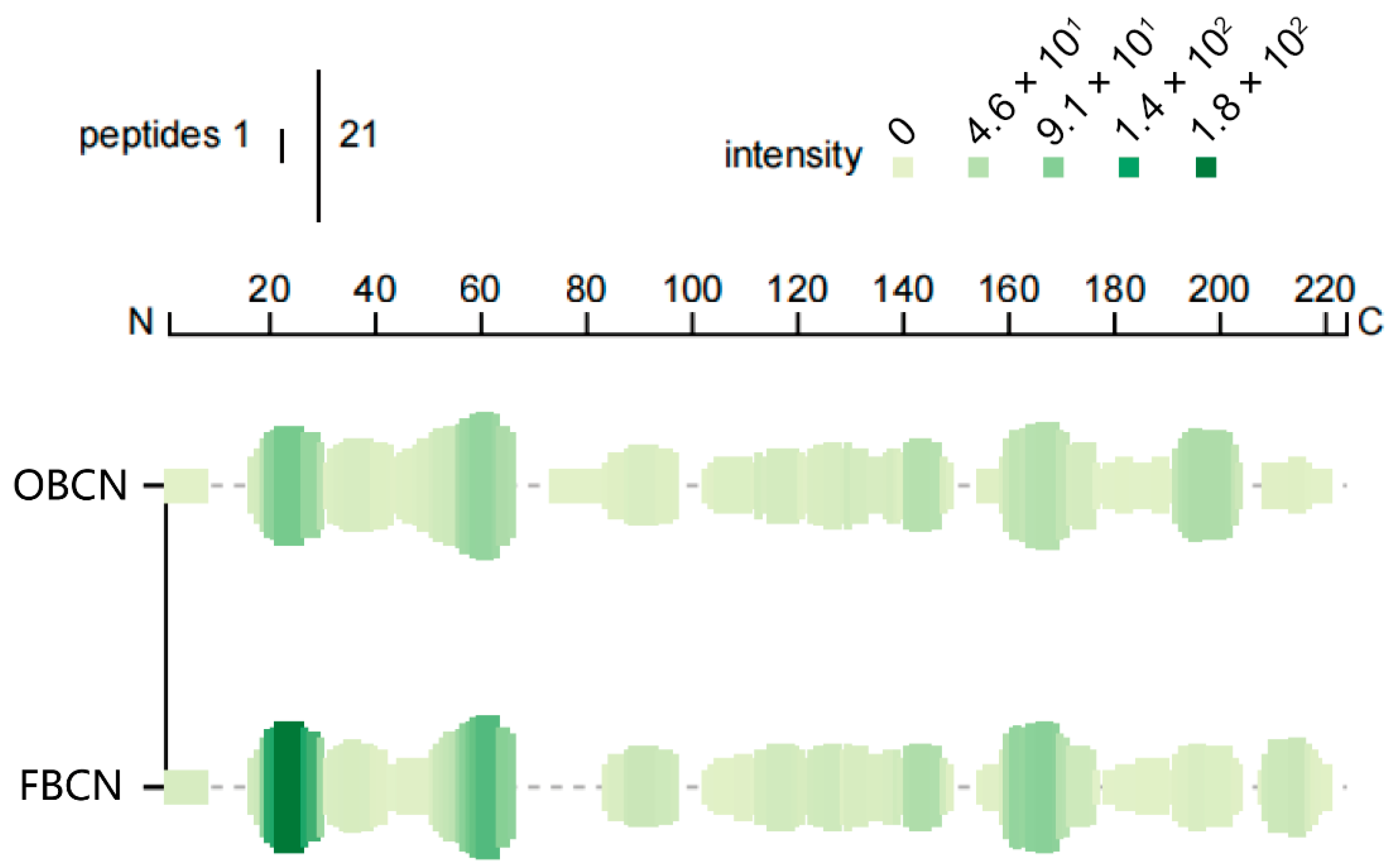

3.3.3. Peptide Profile Originated from β-CN

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Han, M.; Wang, X.; Zhang, K.; Szeto, I.M.-Y.; Duan, S.; Yan, Y.; Liu, B.; Hettinga, K.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, P. How α-lactalbumin and β-casein level in infant formula influence the protein and minerals absorption properties by using Caco-2 cell model. Food Biosci. 2024, 59, 103948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Lin, Y.; Xue, P.; Wang, K.; Xue, Y.; Chen, Y.; Qian, W.; Liu, A.; Guo, H. Pilot-scale co-enrichment of beta-casein and whey protein from skim milk via ceramic membrane cold microfiltration. Appl. Food Res. 2025, 5, 100942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Fan, R.; Wang, Y.; Munir, M.; Li, C.; Wang, C.; Hou, Z.; Zhang, G.; Liu, L.; He, J. Bovine milk β-casein: Structure, properties, isolation, and targeted application of isolated products. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2024, 23, e13311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holgersen, K.; Muk, T.; Ghisari, M.; Arora, P.; Kvistgaard, A.S.; Nielsen, S.D.-H.; Sangild, P.T.; Bering, S.B. Neonatal gut and immune responses to β-casein enriched formula in piglets. J. Nutr. 2024, 154, 2143–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Rooney, H.; Dold, C.; Bavaro, S.; Tobin, J.; Callanan, M.J.; Brodkorb, A.; Lawlor, P.G.; Giblin, L. Membrane filtration processing of infant milk formula alters protein digestion in young pigs. Food Res. Int. 2023, 166, 112577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herreman, L.; Nommensen, P.; Pennings, B.; Laus, M.C. Comprehensive overview of the quality of plant- and animal-sourced proteins based on the digestible indispensable amino acid score. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 5379–5391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martineau-Côté, D.; Achouri, A.; Pitre, M.; Karboune, S.; L’Hocine, L. Improved in vitro gastrointestinal digestion protocol mimicking brush border digestion for the determination of the Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score (DIAAS) of different food matrices. Food Res. Int. 2024, 178, 113932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Yang, T.; Liu, X.; Hemar, Y.; Regenstein, J.M.; Zhou, P. Membrane-based fractionation, enzymatic dephosphorylation, and gastrointestinal digestibility of beta-casein enriched serum protein ingredients. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 88, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhang, L.; Lan, H.; Zhou, P. How to adjust α-lactalbumin and β-casein ratio in milk protein formula to give a similar digestion pattern to human milk? J. Food Compos. Anal. 2022, 110, 104536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Guo, H. The self-association properties of partially dephosphorylated bovine beta-casein. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 134, 108019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiee Tari, N.; Arranz, E.; Corredig, M. Effect of protein composition of a model dairy matrix containing various levels of beta-casein on the structure and anti-inflammatory activity of in vitro digestates. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 1870–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernell, O. Human milk vs. Cow’s milk and the evolution of infant formulas. In Milk and Milk Products in Human Nutrition; Clemens, R.A., Hernell, O., Michaelsen, K.M., Eds.; Karger: Basel, Switzerland, 2011; Volume 67, pp. 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, A.; Cox, W. Comparative nutritive value of casein and lactalbumin for man. J. Nutr. 1947, 34, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hettinga, K.; Pellis, L.; Rombouts, W.; Du, X.; Grigorean, G.; Lonnerdal, B. Effect of pH and protein composition on proteolysis of goat milk proteins by pepsin and pancreatin. Food Res. Int. 2023, 173, 113294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wada, Y.; Phinney, B.S.; Weber, D.; Lonnerdal, B. In vivo digestomics of milk proteins in human milk and infant formula using a suckling rat pup model. Peptides 2017, 88, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, Y.; Loennerdal, B. Effects of different industrial heating processes of milk on site-specific protein modifications and their relationship to in vitro and in vivo digestibility. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 4175–4185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, Y.; Loennerdal, B. Effects of industrial heating processes of milk-based enteral formulas on site-specific protein modifications and their relationship to in vitro and in vivo protein digestibility. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 6787–6798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Sun, Y.; He, T.; Lu, Y.; Szeto, I.M.-Y.; Duan, S.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; et al. Synergistic effect of lactoferrin and osteopontin on intestinal barrier injury. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 127416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, S.D.; Beverly, R.L.; Qu, Y.; Dallas, D.C. Milk bioactive peptide database: A comprehensive database of milk protein-derived bioactive peptides and novel visualization. Food Chem. 2017, 232, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manguy, J.; Jehl, P.; Dillon, E.T.; Davey, N.E.; Shields, D.C.; Holton, T.A. Peptigram: A web-based application for peptidomics data visualization. J. Proteome Res. 2017, 16, 712–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Du, X.; Jiang, S.; Xie, Q.; Mu, G.; Wu, X. Formulation of infant formula with different casein fractions and their effects on physical properties and digestion characteristics. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 769–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiee Tari, N.; Fan, M.Z.; Archbold, T.; Arranz, E.; Corredig, M. Effect of milk protein composition and amount of β-casein on growth performance, gut hormones, and inflammatory cytokines in an in vivo piglet model. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 8604–8613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huppertz, T.; Chia, L.W. Milk protein coagulation under gastric conditions: A review. Int. Dairy J. 2021, 113, 104882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, A.; Cui, J.; Dalgleish, D.; Singh, H. Formation of a structured clot during the gastric digestion of milk: Impact on the rate of protein hydrolysis. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 52, 478–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, A.; Cui, J.; Dalgleish, D.; Singh, H. The formation and breakdown of structured clots from whole milk during gastric digestion. Food Funct. 2016, 7, 4259–4266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demers-Mathieu, V.; Gauthier, S.F.; Britten, M.; Fliss, I.; Robitaille, G.; Jean, J. Antibacterial activity of peptides extracted from tryptic hydrolyzate of whey protein by nanofiltration. Int. Dairy J. 2013, 28, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, S.T.; Martínez-Maqueda, D.; Recio, I.; Hernández-Ledesma, B. Dipeptidyl peptidase-IV inhibitory peptides generated by tryptic hydrolysis of a whey protein concentrate rich in β-lactoglobulin. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 1072–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, O.; Fernández, A.; Norris, R.; Riera, F.A.; Fitzgerald, R.J. Selective enrichment of bioactive properties during ultrafiltration of a tryptic digest of β-lactoglobulin. J. Funct. Foods 2014, 9, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaas, H.; Eriksen, E.; Sekse, C.; Comi, I.; Flengsrud, R.; Holm, H.; Jensen, E.; Jacobsen, M.; Langsrud, T.; Vegarud, G.E. Antibacterial peptides derived from caprine whey proteins, by digestion with human gastrointestinal juice. Br. J. Nutr. 2011, 106, 896–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Hui, Y.; Gao, T.; Shu, G.; Chen, H. Function and characterization of novel antioxidant peptides by fermentation with a wild Lactobacillus plantarum 60. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 135, 110162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihlanto-Leppala, A.; Rokka, T.; Korhonen, H. Angiotensin I converting enzyme inhibitory peptides derived from bovine milk proteins. Int. Dairy J. 1998, 8, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedaghati, M.; Ezzatpanah, H.; Boojar, M.M.A.; Ebrahimi, M.T.; Kobarfard, F. Isolation and identification of some antibacterial peptides in the plasmin-digest of beta-casein. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 68, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perpetuo, E.A.; Juliano, L.; Lebrun, I. Biochemical and pharmacological aspects of two bradykinin-potentiating peptides obtained from tryptic hydrolysis of casein. J. Protein Chem. 2003, 22, 601–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plaisancié, P.; Boutrou, R.; Estienne, M.; Henry, G.; Jardin, J.; Paquet, A.; Léonil, J. Beta-casein(94-123)-derived peptides differently modulate production of mucins in intestinal goblet cells. J. Dairy Res. 2014, 82, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Govindasamy-Lucey, S.; Lucey, J.A. Angiotensin-I-converting enzyme-inhibitory peptides in commercial Wisconsin Cheddar cheeses of different ages. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowmya, K.; Bhat, M.I.; Bajaj, R.K.; Kapila, S.; Kapila, R. Buffalo milk casein derived decapeptide (YQEPVLGPVR) having bifunctional anti-inflammatory and antioxidative features under cellular milieu. Int. J. Pept. Res. Ther. 2018, 25, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Tu, M.; Cheng, S.; Chen, H.; Wang, Z.; Du, M. An anticoagulant peptide from beta-casein: Identification, structure and molecular mechanism. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 886–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayser, H.; Meisel, H. Stimulation of human peripheral blood lymphocytes by bioactive peptides derived from bovine milk proteins. FEBS Lett. 1999, 383, 18–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Ledesma, B.; Amigo, L.; Ramos, M.; Recio, I. Release of angiotensin converting enzyme-inhibitory peptides by simulated gastrointestinal digestion of infant formulas. Int. Dairy J. 2004, 14, 889–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amigo, L.; Martínez-Maqueda, D.; Hernández-Ledesma, B. In silico and in vitro analysis of multifunctionality of animal food-derived peptides. Foods 2020, 9, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubynin, V.A.; Asmakova, L.S.; Sokhanenkova, N.Y.; Bespalova, Z.D.; Nezavibat’ko, V.N.; Kamenskii, A.A. Comparative analysis of neurotropic activity of exorphines, derivatives of dietary proteins. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 1998, 125, 131–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Miao, J.F.; Ma, C.; Sun, G.J.; Zhang, Y.S. Beta-casomorphin-7 cause decreasing in oxidative stress and inhibiting NF-κB-iNOS-NO signal pathway in pancreas of diabetes rats. J. Food Sci. 2012, 77, 278–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haq, M.R.U.; Kapila, R.; Saliganti, V. Consumption of β-casomorphins-7/5 induce inflammatory immune response in mice gut through Th2 pathway. J. Funct. Foods 2014, 8, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoghbi, S.; Trompette, A.; Claustre, J.; Homsi, M.E.; Garzón, J.; Jourdan, G.; Scoazec, J.-Y.; Plaisancié, P. Beta-casomorphin-7 regulates the secretion and expression of gastrointestinal mucins through a μ-opioid pathway. Am. J. Physiol.-Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2006, 290, 1105–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trompette, A.; Claustre, J.; Caillon, F.; Jourdan, G.; Chayvialle, J.A.; Plaisancié, P. Milk bioactive peptides and β-casomorphins induce mucus release in rat jejunum. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 3499–3503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claustre, J.; Toumi, F.; Trompette, A.; Jourdan, G.; Guignard, H.; Chayvialle, J.A.; Plaisancié, P. Effects of peptides derived from dietary proteins on mucus secretion in rat jejunum. Am. J. Physiol.-Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2002, 283, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sienkiewicz-Szłapka, E.; Jarmołowska, B.; Krawczuk, S.; Kostyra, E.; Kostyra, H.; Iwan, M. Contents of agonistic and antagonistic opioid peptides in different cheese varieties. Int. Dairy J. 2009, 19, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S.V.; Pihlanto, A.; Malcata, F.X. Bioactive peptides in ovine and caprine cheeselike systems prepared with proteases from Cynara cardunculus. J. Dairy Sci. 2006, 89, 3336–3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagardia, I.; Iloro, I.; Elortza, F.; Bald, C. Quantitative structure–activity relationship based screening of bioactive peptides identified in ripened cheese. Int. Dairy J. 2013, 33, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.; Sawh, F.; Green-Johnson, J.M.; Taggart, H.J.; Strap, J.L. Characterization of casein-derived peptide bioactivity: Differential effects on angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition and cytokine and nitric oxide production. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 5805–5815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basilicata, M.; Pepe, G.; Adesso, S.; Ostacolo, C.; Sala, M.; Sommella, E.; Scala, M.; Messore, A.; Autore, G.; Marzocco, S.; et al. Antioxidant properties of buffalo-milk dairy products: A β-lg peptide released after gastrointestinal digestion of buffalo ricotta cheese reduces oxidative stress in intestinal epithelial cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, M.; Stanton, C.; Slattery, H.; O’sullivan, O.; Hill, C.; Fitzgerald, G.F.; Ross, R.P. Casein fermentate of Lactobacillus animalis DPC6134 contains a range of novel propeptide angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 4658–4667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaoka, S.; Futamura, Y.; Miwa, K.; Awano, T.; Yamauchi, K.; Kanamaru, Y.; Tadashi, K.; Kuwata, T. Identification of novel hypocholesterolemic peptides derived from bovine milk β-lactoglobulin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001, 281, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.; Zhang, L.-W.; Han, X.; Cheng, D.-Y. Novel angiotensin I-converting enzyme inhibitory peptides from protease hydrolysates of Qula casein: Quantitative structure-activity relationship modeling and molecular docking study. J. Funct. Foods 2017, 32, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Cui, Y.J.; Bai, S.S.; Yang, Z.J.; Miao, C.; Megrous, S.; Aziz, T.; Sarwar, A.; Li, D.; Yang, Z.N. Antioxidant activity of novel casein-derived peptides with microbial proteases as characterized via Keap1-Nrf2 pathway in HepG2 cells. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 31, 1163–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hata, I.; Higashiyama, S.; Otani, H. Identification of a phosphopeptide in bovine αs1-casein digest as a factor influencing proliferation and immunoglobulin production in lymphocyte cultures. J. Dairy Res. 1998, 65, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Rivera, L.; Menard, O.; Recio, I.; Dupont, D. Peptide mapping during dynamic gastric digestion of heated and unheated skimmed milk powder. Food Res. Int. 2015, 77, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Yu, Y.; Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Szeto, I.M.; Jin, Y. Effect of sample preparation on analysis of human milk endogenous peptides using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Chin. J. Chromatogr. 2021, 39, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ingredients (mg) | OBCN | FBCN |

|---|---|---|

| Whey protein isolate | 266.9 | 267.8 |

| Casein | 174.0 | 94.7 |

| β-CN | - | 89.6 |

| Whey protein/casein ratio | 60:40 | 60:40 |

| Total protein content (mg/mL) | 20.0 | 20.1 |

| β-casein content in casein (%) | 43.0% | 63.4% |

| Classification | Peptide Sequence a | Bioactive Sequence (MBPDB) b | Bioactivity c | Parent Protein | References d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Significantly upregulated | RTPEVDDEALE | TPEVDDEALEK, TPEVDKEALE, TPEVDKEALEK | Antimicrobial, Antioxidant, DPP-IV Inhibitory | β-LG | [26,27,28,29,30] |

| KEMPFPK | EMPFPK, HKEMPFPK | Antimicrobial, ACE-inhibitory, Increase mucin secretion | β-CN | [31,32,33,34] | |

| EPVLGPVR | EPVLGPVRGP, YQEPVLGPVR | Immunomodulatory, Antioxidant, ACE-inhibitory, Antithrombotic | β-CN | [35,36,37,38] | |

| YPFPGPIH | VYPFPGPI, YPFPGPIP, YPFPGPI | Immunomodulatory, Increase mucin secretion, Opioid, ACE-inhibitory, Antianxiety, Antioxidant | β-CN | [39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47] | |

| PFPGPIHNSLPQ | PFTGPIPNSLPQ | Antimicrobial | β-CN | [29] | |

| YQEPVLGPV | YQEPVLGP, YQEPVLGPVRG, YQEPVLGPVR, LYQEPVLGPVR | Immunomodulatory, Antioxidant, ACE-inhibitory | β-CN | [35,36,48,49,50] | |

| YVEELKPTPEG | YVEELKPTPEGDL | Antioxidant | β-CN | [51] | |

| NIPPLTQTPVVVPPFLQPEV | NIPPLTQTPVVVPPFLQ | ACE-inhibitory | β-CN | [52] | |

| KGLDIQK | GLDIQK | ACE-inhibitory, Cholesterol regulation | β-LG | [31,53] | |

| PFPGPIHN | PFPGPIPN | ACE-inhibitory | β-CN | [54] | |

| Significantly down-regulated | DIPNPIGSENS | FSDIPNPIGSE, FSDIPNPIGSEN | Antioxidant | αs1-CN | [55] |

| HQPLPPTVMFPPQS | HQPHQPLPPTVMFPPQ | Immunomodulatory, ACE-inhibitory | β-CN | [50] | |

| EMPFPKYPVE | MPFPKYPVEP | ACE-inhibitory | β-CN | [52] | |

| EAESISSSEEIVPNSVEQ | QMEAESISSSEEIVPNSVEQK | Immunomodulatory | αs1-CN | [56] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Song, S.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, H. Effect of β-Casein Fortification in Milk Protein on Digestion Properties and Release of Bioactive Peptides in a Suckling Rat Pup Model. Foods 2026, 15, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010026

Song S, Lin Y, Zhang Y, Guo H. Effect of β-Casein Fortification in Milk Protein on Digestion Properties and Release of Bioactive Peptides in a Suckling Rat Pup Model. Foods. 2026; 15(1):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010026

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Sijia, Yingying Lin, Yuning Zhang, and Huiyuan Guo. 2026. "Effect of β-Casein Fortification in Milk Protein on Digestion Properties and Release of Bioactive Peptides in a Suckling Rat Pup Model" Foods 15, no. 1: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010026

APA StyleSong, S., Lin, Y., Zhang, Y., & Guo, H. (2026). Effect of β-Casein Fortification in Milk Protein on Digestion Properties and Release of Bioactive Peptides in a Suckling Rat Pup Model. Foods, 15(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010026