Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Traditional Dry-Cured Fermented Foods with Probiotic Effect: Selection, Mechanisms of Action and Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. LAB Activities in Dry-Cured Fermented Foods: Possible Candidates as Probiotic Strains

3. The Benefit of Probiotic LAB in Fermented Foods

4. Compatibility of Probiotic LAB with Fermented Foods Matrices

5. Selection of LAB with Probiotic Effect from Traditional Dry-Cured Fermented Foods

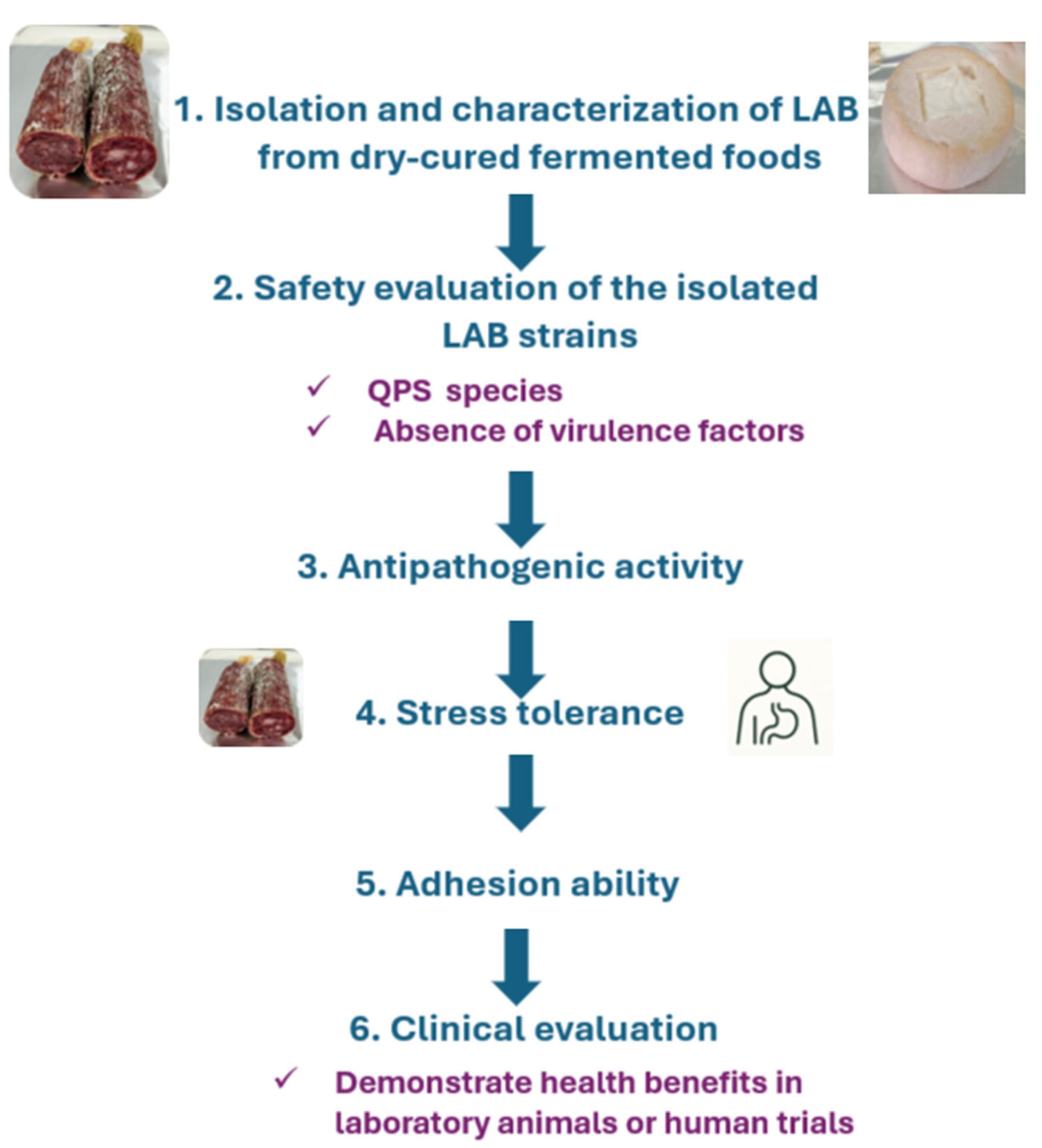

5.1. Isolation and Characterization of LAB from Dry-Cured Fermented Foods

5.2. Safety Evaluation of the Isolated Strains

5.3. Antipathogenic Activity

5.4. Stress Tolerance

5.5. Adhesion Ability

5.6. Clinical Evaluation

6. LAB with Probiotic Effect Isolated from Fermented Foods

7. Probiotics in Plant-Based Analogues

8. Multi-Omics Strategies to Probiotic Selection and Applications

9. Industrial Requirements for the Exploitation of LAB Selected as Probiotics

10. Perspectives and Future Remarks

11. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cuamatzin-García, L.; Rodríguez-Rugarcía, P.; El-Kassis, E.G.; Galicia, G.; Meza-Jiménez, M.d.L.; Baños-Lara, M.D.R.; Zaragoza-Maldonado, D.S.; Pérez-Armendáriz, B. Traditional Fermented Foods and Beverages from around the World and Their Health Benefits. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdolec, N.; Mikuš, T.; Kiš, M. Lactic Acid Bacteria in Meat Fermentation: Dry Sausage Safety and Quality. In Lactic Acid Bacteria in Food Biotechnology: Innovations and Functional Aspects; Elsevier Science Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 145–159. ISBN 9780323898751. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, Y.; Guo, T.; Qiao, M. Current Application and Future Prospects of CRISPR-Cas in Lactic Acid Bacteria: A Review. Food Res. Int. 2025, 209, 116315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adebayo-Tayo, B.C.; Ogundele, B.R.; Ajani, O.A.; Olaniyi, O.A. Characterization of Lactic Acid Bacterium Exopolysaccharide, Biological, and Nutritional Evaluation of Probiotic Formulated Fermented Coconut Beverage. Int. J. Food Sci. 2024, 2024, 8923217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zapaśnik, A.; Sokołowska, B.; Bryła, M. Role of Lactic Acid Bacteria in Food Preservation and Safety. Foods 2022, 11, 1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, S.A.; Ayivi, R.D.; Zimmerman, T.; Siddiqui, S.A.; Altemimi, A.B.; Fidan, H.; Esatbeyoglu, T.; Bakhshayesh, R.V. Lactic Acid Bacteria as Antimicrobial Agents: Food Safety and Microbial Food Spoilage Prevention. Foods 2021, 10, 3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.C.; Lin, C.H.; Sung, C.T.; Fang, J.Y. Antibacterial Activities of Bacteriocins: Application in Foods and Pharmaceuticals. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 91530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, D.; de Ullivarri, M.F.; Ross, R.P.; Hill, C. After a Century of Nisin Research-Where Are We Now? FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2023, 47, fuad023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradisteanu Pircalabioru, G.; Popa, L.I.; Marutescu, L.; Gheorghe, I.; Popa, M.; Czobor Barbu, I.; Cristescu, R.; Chifiriuc, M.C. Bacteriocins in the Era of Antibiotic Resistance: Rising to the Challenge. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcelli, V.; Osimani, A.; Aquilanti, L. Research Progress in the Use of Lactic Acid Bacteria as Natural Biopreservatives against Pseudomonas Spp. in Meat and Meat Products: A Review. Food Res. Int. 2024, 196, 115129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryukhanov, A.L.; Klimko, A.I.; Netrusov, A.I. Antioxidant Properties of Lactic Acid Bacteria. Microbiology 2022, 91, 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, P.; Tiwari, S.K. Health Benefits of Bacteriocins Produced by Probiotic Lactic Acid Bacteria. In Microbial Biomolecules: Emerging Approach in Agriculture, Pharmaceuticals and Environment Management; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteagudo-Mera, A.; Rastall, R.A.; Gibson, G.R.; Charalampopoulos, D.; Chatzifragkou, A. Adhesion Mechanisms Mediated by Probiotics and Prebiotics and Their Potential Impact on Human Health. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 6463–6472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Hao, L.; Zhou, R.; Jin, Y.; Huang, J.; Wu, C. Multispecies Biofilms in Fermentation: Biofilm Formation, Microbial Interactions, and Communication. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 3346–3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leska, A.; Nowak, A.; Czarnecka-Chrebelska, K.H. Adhesion and Anti-Adhesion Abilities of Potentially Probiotic Lactic Acid Bacteria and Biofilm Eradication of Honeybee (Apis mellifera L.) Pathogens. Molecules 2022, 27, 8945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poimenidou, S.V.; Skarveli, A.; Saxami, G.; Mitsou, E.K.; Kotsou, M.; Kyriacou, A. Inhibition of Listeria Monocytogenes Growth, Adherence and Invasion in Caco-2 Cells by Potential Probiotic Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Fecal Samples of Healthy Neonates. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mgomi, F.C.; Yang, Y.-R.; Cheng, G.; Yang, Z.-Q. Lactic Acid Bacteria Biofilms and Their Antimicrobial Potential against Pathogenic Microorganisms. Biofilm 2023, 5, 100118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhang, L.; Qu, X. Research Progress on the Regulatory Mechanism of Biofilm Formation in Probiotic Lactic Acid Bacteria. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 65, 4869–4883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, J.; Teixeira, P. Biotechnology Approaches in Food Preservation and Food Safety. Foods 2022, 11, 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santa, D.; Huch, M.; Stoll, D.A.; Cunedioglu, H.; Priidik, R.; Karakaş-Budak, B.; Matalas, A.; Pennone, V.; Girija, A.; Arranz, E.; et al. Health Benefits of Ethnic Fermented Foods. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1677478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soemarie, Y.B.; Milanda, T.; Barliana, M.I. Fermented Foods as Probiotics: A Review. J. Adv. Pharm. Technol. Res. 2021, 12, 335–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Burgos, M.; Moreno-Fernández, J.; Alférez, M.J.M.; Díaz-Castro, J.; López-Aliaga, I. New Perspectives in Fermented Dairy Products and Their Health Relevance. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 72, 104059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, G.N.; Gu, R.; Qu, H.; Bahar Khaskheli, G.; Rashid Rajput, I.; Qasim, M.; Chen, X. Therapeutic Potential of Popular Fermented Dairy Products and Its Benefits on Human Health. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1328620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yerlikaya, O. A Review of Fermented Milks: Potential Beneficial Effects on Human Nutrition and Health. Afr. Health Sci. 2023, 23, 498–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasika, D.M.D.; Vidanarachchi, J.K.; Luiz, S.F.; Azeredo, D.R.P.; Cruz, A.G.; Ranadheera, C.S. Probiotic Delivery through Non-Dairy Plant-Based Food Matrices. Agriculture 2021, 11, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngamsamer, C.; Muangnoi, C.; Tongkhao, K.; Sae-Tan, S.; Treesuwan, K.; Sirivarasai, J. Potential Health Benefits of Fermented Vegetables with Additions of Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus GG and Polyphenol Vitexin Based on Their Antioxidant Properties and Prohealth Profiles. Foods 2024, 13, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Cruz Nascimento, S.S.; Passos, T.S.; de Sousa Júnior, F.C. Probiotics in Plant-Based Food Matrices: A Review of Their Health Benefits. PharmaNutrition 2024, 28, 100390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munekata, P.E.S.; Pateiro, M.; Tomasevic, I.; Domínguez, R.; da Silva Barretto, A.C.; Santos, E.M.; Lorenzo, J.M. Functional Fermented Meat Products with Probiotics—A Review. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 133, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani-López, E.; Hernández-Figueroa, R.H.; López-Malo, A.; Morales-Camacho, J.I. Viability and Functional Impact of Probiotic and Starter Cultures in Salami-Type Fermented Meat Products. Front. Chem. 2024, 12, 1507370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukel, O.; Sengun, I. Production of Probiotic Fermented Salami Using Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus, Lactiplantibacillus plantarum, and Bifidobacterium lactis. J. Food Sci. 2024, 89, 2956–2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akamine, I.T.; Mansoldo, F.R.P.; Vermelho, A.B. Probiotics in the Sourdough Bread Fermentation: Current Status. Fermentation 2023, 9, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Márquez-Morales, L.; El-Kassis, E.G.; Cavazos-Arroyo, J.; Rocha-Rocha, V.; Martínez-Gutiérrez, F.; Pérez-Armendáriz, B. Effect of the Intake of a Traditional Mexican Beverage Fermented with Lactic Acid Bacteria on Academic Stress in Medical Students. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albene, D.; Lema, N.K.; Tesfaye, G.; Andeta, A.F.; Ali, K.; Guadie, A. Probiotic Potential of Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Ethiopian Traditional Fermented Cheka Beverage. Ann. Microbiol. 2024, 74, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Hakim, B.N.; Xuan, N.J.; Oslan, S.N.H. A Comprehensive Review of Bioactive Compounds from Lactic Acid Bacteria: Potential Functions as Functional Food in Dietetics and the Food Industry. Foods 2023, 12, 2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadare, O.S.; Anyadike, C.H.; Momoh, A.O.; Bello, T.K. Antimicrobial Properties, Safety, and Probiotic Attributes of Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Sauerkraut. Afr. J. Clin. Exp. Microbiol. 2023, 24, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Lai, S.; Zhou, Z.; Yang, J.; Liu, H.; Zhong, Z.; Fu, H.; Ren, Z.; Shen, L.; Cao, S.; et al. Screening and Evaluation of Lactic Acid Bacteria with Probiotic Potential from Local Holstein Raw Milk. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 918774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel Tawab, F.I.; Abd Elkadr, M.H.; Sultan, A.M.; Hamed, E.O.; El-Zayat, A.S.; Ahmed, M.N. Probiotic Potentials of Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Egyptian Fermented Food. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 16601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsov, A.; Tsigoriyna, L.; Batovska, D.; Armenova, N.; Mu, W.; Zhang, W.; Petrov, K.; Petrova, P. Bacterial Degradation of Antinutrients in Foods: The Genomic Insight. Foods 2024, 13, 2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obayomi, O.V.; Olaniran, A.F.; Owa, S.O. Effects of Bioprocessing on Elemental Composition, Physicochemical, Techno-Functional, Storage and Sensorial Properties of Gluten-Free Flour from Fonio and Date Fruit. Food Biosci. 2024, 62, 105143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaniran, A.F.; Agaja, F.O.; Obayomi, O.V.; Ebong, S.I.; Malomo, A.A.; Olaniran, O.D.; Erinle, O.C.; Owa, S.O. Comparative Effect of Boiling, Microwave and Ultrasonication Treatment on Microstructure, Nutritional and Microbial Quality of Tofu. Appl. Food Res. 2025, 5, 100750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Singh, N. Probiotics for Children Involvement in Ameliorating Children’s Health. In Probiotics: A Comprehensive Guide to Enhance Health and Mitigate Disease; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 95–128. ISBN 9781040036167. [Google Scholar]

- Anumudu, C.K.; Miri, T.; Onyeaka, H. Multifunctional Applications of Lactic Acid Bacteria: Enhancing Safety, Quality, and Nutritional Value in Foods and Fermented Beverages. Foods 2024, 13, 3714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, M.N.; Elmaghraby, M.M.; Abdellatif, A.A.; Salem, S.R.; Salama, M.M.; Maksoud, O.A.A.; Nasr, R.M.; Amer, M.N.; Marghany, M.M.; Awad, H.M. Probiotics as Promoters of Human Health. Nov. Res. Microbiol. J. 2024, 8, 2580–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, A.; Agrawal, M. Controlling Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis with Probiotic Lactic Acid Bacteria That Produce Bacteriocins. Int. J. Res. 2024, 12, 766–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Rivera, Y.; Sánchez-Vega, R.; Gutiérrez-Méndez, N.; León-Félix, J.; Acosta-Muñiz, C.; Sepulveda, D.R. Production of Reuterin in a Fermented Milk Product by Lactobacillus Reuteri: Inhibition of Pathogens, Spoilage Microorganisms, and Lactic Acid Bacteria. J. Dairy. Sci. 2017, 100, 4258–4268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parsaeimehr, M.; Azizkhani, M.; Javan, A.J. The Inhibitory Effects of 2 Commercial Probiotic Strains on the Growth of Staphylococcus aureus and Gene Expression of Enterotoxin A. Int. J. Enteric Pathog. 2017, 5, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.C.; Lin, P.P.; Hsieh, Y.M.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Wu, H.C.; Huang, C.C. Cholesterol-Lowering Potentials of Lactic Acid Bacteria Based on Bile-Salt Hydrolase Activity and Effect of Potent Strains on Cholesterol Metabolism In Vitro and In Vivo. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 690752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco, M.L.; Sanders, M.E.; Gänzle, M.; Arrieta, M.C.; Cotter, P.D.; De Vuyst, L.; Hill, C.; Holzapfel, W.; Lebeer, S.; Merenstein, D.; et al. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) Consensus Statement on Fermented Foods. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermolenko, E.I.; Desheva, Y.A.; Kolobov, A.A.; Kotyleva, M.P.; Sychev, I.A.; Suvorov, A.N. Anti–Influenza Activity of Enterocin B In Vitro and Protective Effect of Bacteriocinogenic Enterococcal Probiotic Strain on Influenza Infection in Mouse Model. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2019, 11, 705–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Gänzle, M.G. Host-Adapted Lactobacilli in Food Fermentations: Impact of Metabolic Traits of Host Adapted Lactobacilli on Food Quality and Human Health. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2020, 31, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fijan, S.; Fijan, P.; Wei, L.; Marco, M.L. Health Benefits of Kimchi, Sauerkraut, and Other Fermented Foods of the Genus Brassica. Appl. Microbiol. 2024, 4, 1165–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, M.; Mora, L.; Toldrá, F. Characterisation of the Antioxidant Peptide AEEEYPDL and Its Quantification in Spanish Dry-Cured Ham. Food Chem. 2018, 258, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Liu, J.; Zhang, D.; Tan, Y.; Feng, W.; Peng, C. Gut Microbiota, Bile Acids, and Nature Compounds. Phytother. Res. 2022, 36, 3102–3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawardena, S.; Nadeeshani, H.; Amarasinghe, V.; Liyanage, R. Bioactive Properties and Therapeutic Aspects of Fermented Vegetables: A Review. Food Prod. Process. Nutr. 2024, 6, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarıtaş, S.; Portocarrero, A.C.M.; Miranda López, J.M.; Lombardo, M.; Koch, W.; Raposo, A.; El-Seedi, H.R.; de Brito Alves, J.L.; Esatbeyoglu, T.; Karav, S.; et al. The Impact of Fermentation on the Antioxidant Activity of Food Products. Molecules 2024, 29, 3941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, F.; Chen, M.F.; Chen, J.; Li, C.; Zhou, C.; Hong, P.; Sun, S.; Qian, Z.J. Boiled Abalone Byproduct Peptide Exhibits Anti-Tumor Activity in HT1080 Cells and HUVECs by Suppressing the Metastasis and Angiogenesis in Vitro. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 8855–8867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkhtab, E.; El-Alfy, M.; Shenana, M.; Mohamed, A.; Yousef, A.E. New Potentially Antihypertensive Peptides Liberated in Milk during Fermentation with Selected Lactic Acid Bacteria and Kombucha Cultures. J. Dairy. Sci. 2017, 100, 9508–9520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, A.K.; Sanjukta, S.; Jeyaram, K. Production of Angiotensin I Converting Enzyme Inhibitory (ACE-I) Peptides during Milk Fermentation and Their Role in Reducing Hypertension. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 2789–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oniszczuk, A.; Oniszczuk, T.; Gancarz, M.; Szymańska, J. Role of Gut Microbiota, Probiotics and Prebiotics in the Cardiovascular Diseases. Molecules 2021, 26, 1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flach, J.; van der Waal, M.B.; van den Nieuwboer, M.; Claassen, E.; Larsen, O.F.A. The Underexposed Role of Food Matrices in Probiotic Products: Reviewing the Relationship between Carrier Matrices and Product Parameters. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 2570–2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kailasapathy, K. Survival of Free and Encapsulated Probiotic Bacteria and Their Effect on the Sensory Properties of Yoghurt. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2006, 39, 1221–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcial-Coba, M.S.; Knøchel, S.; Nielsen, D.S. Low-Moisture Food Matrices as Probiotic Carriers. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2019, 366, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bellis, P.; Sisto, A.; Lavermicocca, P. Probiotic Bacteria and Plant-Based Matrices: An Association with Improved Health-Promoting Features. J. Funct. Foods 2021, 87, 104821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meybodi, N.M.; Mortazavian, A.M.; Arab, M.; Nematollahi, A. Probiotic Viability in Yoghurt: A Review of Influential Factors. Int. Dairy. J. 2020, 109, 104793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vuyst, L.; Leroy, F. Functional Role of Yeasts, Lactic Acid Bacteria and Acetic Acid Bacteria in Cocoa Fermentation Processes. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 44, 432–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín, I.; Rodríguez, A.; Sánchez-Montero, L.; Padilla, P.; Córdoba, J.J. Effect of the Dry-Cured Fermented Sausage “Salchichón” Processing with a Selected Lactobacillus sakei in Listeria monocytogenes and Microbial Population. Foods 2021, 10, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talon, R.; Leroy, S.; Lebert, I. Microbial Ecosystems of Traditional Fermented Meat Products: The Importance of Indigenous Starters. Meat Sci. 2007, 77, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, F.; Verluyten, J.; De Vuyst, L. Functional Meat Starter Cultures for Improved Sausage Fermentation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2006, 106, 270–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou, K.; Alegría, Á.; Bron, P.A.; de Angelis, M.; Gobbetti, M.; Kleerebezem, M.; Lemos, J.A.; Linares, D.M.; Ross, P.; Stanton, C.; et al. Stress Physiology of Lactic Acid Bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2016, 80, 837–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Probiotics in Food Health and Nutritional Properties and Guidelines for Evaluation; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2006; ISBN 92-5-105513-0. [Google Scholar]

- Vinderola, G.; Cotter, P.D.; Freitas, M.; Gueimonde, M.; Holscher, H.D.; Ruas-Madiedo, P.; Salminen, S.; Swanson, K.S.; Sanders, M.E.; Cifelli, C.J. Fermented Foods: A Perspective on Their Role in Delivering Biotics. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1196239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Melo Pereira, G.V.; de Oliveira Coelho, B.; Magalhães Júnior, A.I.; Thomaz-Soccol, V.; Soccol, C.R. How to Select a Probiotic? A Review and Update of Methods and Criteria. Biotechnol. Adv. 2018, 36, 2060–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binda, S.; Hill, C.; Johansen, E.; Obis, D.; Pot, B.; Sanders, M.E.; Tremblay, A.; Ouwehand, A.C. Criteria to Qualify Microorganisms as “Probiotic” in Foods and Dietary Supplements. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 563305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wejinya, A.O.; Giami, S.Y.; Barber, L.I.; Obinna-Echem, P.C. Isolation, Identification and Characterization of Potential Probiotics from Fermented Food Products. Asian Food Sci. J. 2022, 21, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, H.I.; Yang, H.-I.; Kim, S.R.; Jeong, C.R.; Eun, J.B.; Kim, T.W. Development a Modified MRS Medium for Enhanced Growth of Psychrotrophic Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Kimchi. LWT 2024, 210, 116815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loo, J.S.; Oslan, S.N.H.; Mokshin, N.A.S.; Othman, R.; Amin, Z.; Dejtisakdi, W.; Prihanto, A.A.; Tan, J.S. Comprehensive Review of Strategies for Lactic Acid Bacteria Production and Metabolite Enhancement in Probiotic Cultures: Multifunctional Applications in Functional Foods. Fermentation 2025, 11, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goa, T.; Beyene, G.; Mekonnen, M.; Gorems, K. Isolation and Characterization of Lactic Acid Bacteria from Fermented Milk Produced in Jimma Town, Southwest Ethiopia, and Evaluation of Their Antimicrobial Activity against Selected Pathogenic Bacteria. Int. J. Food Sci. 2022, 2022, 2076021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdullah, D.; Poddar, S.; Rai, R.P.; Purwati, E.; Dewi, N.P.; Pratama, Y.E. Molecular Identification of Lactic Acid Bacteria an Approach to Sustainable Food Security. J. Public Health Res. 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohania, D.; Nagpal, R.; Kumar, M.; Bhardwaj, A.; Yadav, M.; Jain, S.; Marotta, F.; Singh, V.; Parkash, O.; Yadav, H. Molecular Approaches for Identification and Characterization of Lactic Acid Bacteria. J. Dig. Dis. 2008, 9, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahraman-Ilıkkan, Ö. Comparative Genomics of Four Lactic Acid Bacteria Identified with Vitek MS (MALDI-TOF) and Whole-Genome Sequencing. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2024, 299, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bover-Cid, S.; Holzapfel, W.H. Improved Screening Procedure for Biogenic Amine Production by Lactic Acid Bacteria. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 1999, 53, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiago, I.; Teixeira, I.; Silva, S.; Chung, P.; Veríssimo, A.; Manaia, C.M. Metabolic and Genetic Diversity of Mesophilic and Thermophilic Bacteria Isolated from Composted Municipal Sludge on Poly-ε-Caprolactones. Curr. Microbiol. 2004, 49, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Omar, N.; Castro, A.; Lucas, R.; Abriouel, H.; Yousif, N.M.K.; Franz, C.M.A.P.; Holzapfel, W.H.; Pérez-Pulido, R.; Martínez-Cañamero, M.; Gálvez, A. Functional and Safety Aspects of Enterococci Isolated from Different Spanish Foods. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2004, 27, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, I.; Barbosa, J.; Pereira, S.I.A.; Rodríguez, A.; Córdoba, J.J.; Teixeira, P. Study of Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Traditional Ripened Foods and Partial Characterization of Their Bacteriocins. LWT 2023, 173, 114300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, J.; Gibbs, P.A.; Teixeira, P. Virulence Factors among Enterococci Isolated from Traditional Fermented Meat Products Produced in the North of Portugal. Food Control 2010, 21, 651–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perin, L.M.; Miranda, R.O.; Todorov, S.D.; Franco, B.D.G.d.M.; Nero, L.A. Virulence, Antibiotic Resistance and Biogenic Amines of Bacteriocinogenic Lactococci and Enterococci Isolated from Goat Milk. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2014, 185, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorov, S.D.; Perin, L.M.; Carneiro, B.M.; Rahal, P.; Holzapfel, W.; Nero, L.A. Safety of Lactobacillus Plantarum ST8Sh and Its Bacteriocin. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2017, 9, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-Platero, A.M.; Valdivia, E.; Maqueda, M.; Martínez-Bueno, M. Characterization and Safety Evaluation of Enterococci Isolated from Spanish Goats’ Milk Cheeses. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2009, 132, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, R.H.; Ancuelo, A.E.; Zendo, T. Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of bacteriocinogenic lactic acid bacterial strains for possible beneficial, virulence, and antibiotic resistance traits. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Food Sci. 2022, 11, e4990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Miguélez, J.M.; Robledo, J.; Martín, I.; Castaño, C.; Delgado, J.; Córdoba, J.J. Biocontrol of L. Monocytogenes with Selected Autochthonous Lactic Acid Bacteria in Raw Milk Soft-Ripened Cheese under Different Water Activity Conditions. Foods 2024, 13, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, I.; Rodríguez, A.; Córdoba, J.J. Application of Selected Lactic-Acid Bacteria to Control Listeria Monocytogenes in Soft-Ripened “Torta Del Casar” Cheese. LWT 2022, 168, 113873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.; Guarner, F.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Merenstein, D.J.; Pot, B.; Morelli, L.; Canani, R.B.; Flint, H.J.; Salminen, S.; et al. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics Consensus Statement on the Scope and Appropriate Use of the Term Probiotic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 11, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Cui, Y.; Jia, Q.; Zhuang, Y.; Gu, Y.; Fan, X.; Ding, Y. Response Mechanisms of Lactic Acid Bacteria under Environmental Stress and Their Application in the Food Industry. Food Biosci 2025, 64, 105938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelescu, I.R.; Ionetic, E.C.; Necula-Petrareanu, G.; Grosu-Tudor, S.S.; Zamfir, M. Exploring the Survival Mechanisms of Some Functional Lactic Acid Bacteria under Stress Conditions: Morphological Changes and Cross-Protection. Food Biosci. 2025, 71, 107059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kõll-Klais, P.; Mändar, R.; Leibur, E.; Marcotte, H.; Hammarström, L.; Mikelsaar, M. Oral Lactobacilli in Chronic Periodontitis and Periodontal Health: Species Composition and Antimicrobial Activity. Oral. Microbiol. Immunol. 2005, 20, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shori, A.B. Microencapsulation Improved Probiotics Survival During Gastric Transit. Hayati 2017, 24, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divya, J.B.; Varsha, K.K.; Nampoothiri, K.M. Newly Isolated Lactic Acid Bacteria with Probiotic Features for Potential Application in Food Industry. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2012, 167, 1314–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, M.N.; Tagliapietra, B.L.; do Amaral Flores, V.; dos Santos Richards, N.S.P. In Vitro Test to Evaluate Survival in the Gastrointestinal Tract of Commercial Probiotics. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2021, 4, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turpin, W.; Humblot, C.; Guyot, J.P. Genetic Screening of Functional Properties of Lactic Acid Bacteria in a Fermented Pearl Millet Slurry and in the Metagenome of Fermented Starchy Foods. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 8722–8734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duary, R.K.; Rajput, Y.S.; Batish, V.K.; Grover, S. Assessing the Adhesion of Putative Indigenous Probiotic Lactobacilli to Human Colonic Epithelial Cells. Indian. J. Med. Res. 2011, 134, 664–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, A.M.O.; Miguel, M.A.L.; Peixoto, R.S.; Ruas-Madiedo, P.; Paschoalin, V.M.F.; Mayo, B.; Delgado, S. Probiotic Potential of Selected Lactic Acid Bacteria Strains Isolated from Brazilian Kefir Grains. J. Dairy. Sci. 2015, 98, 3622–3632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, A.L.; Boyte, M.E.; Elkins, C.A.; Goldman, V.S.; Heimbach, J.; Madden, E.; Oketch-Rabah, H.; Sanders, M.E.; Sirois, J.; Smith, A. Considerations for Determining Safety of Probiotics: A USP Perspective. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2022, 136, 105266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, M.E.; Benson, A.; Lebeer, S.; Merenstein, D.J.; Klaenhammer, T.R. Shared Mechanisms among Probiotic Taxa: Implications for General Probiotic Claims. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2018, 49, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Filippis, F.; Pasolli, E.; Ercolini, D. The Food-Gut Axis: Lactic Acid Bacteria and Their Link to Food, the Gut Microbiome and Human Health. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 44, 454–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, T.J.; Salini, S.V.; Mohan, L.; Nandagopal, P.; Arakal, J.J. Functional Metabolites of Probiotic Lactic Acid Bacteria in Fermented Dairy Products. Food Humanit. 2024, 3, 100341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentino, V.; Magliulo, R.; Farsi, D.; Cotter, P.D.; O’Sullivan, O.; Ercolini, D.; De Filippis, F. Fermented Foods, Their Microbiome and Its Potential in Boosting Human Health. Microb. Biotechnol. 2024, 17, e14428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Palestino, A.; Gómez-Vargas, R.; Suárez-Quiroz, M.; González-Ríos, O.; Hernández-Estrada, Z.J.; Castellanos-Onorio, O.P.; Alonso-Villegas, R.; Estrada-Beltrán, A.E.; Figueroa-Hernández, C.Y. Probiotic Potential of Lactic Acid Bacteria and Yeast Isolated from Cocoa and Coffee Bean Fermentation: A Review. Fermentation 2025, 11, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E.; Yun, J.H.; Lee, E.; Hong, S.P. Untargeted Metabolomics Reveals Doenjang Metabolites Affected by Manufacturing Process and Microorganisms. Food Res. Int. 2022, 157, 111422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Z.; Chen, M.; Chen, Y.; Sun, H. The Probiotic Potential, Safety, and Immunomodulatory Properties of Levilactobacillus brevis ZG2488: A Novel Strain Isolated from Healthy Human Feces. Fermentation 2025, 11, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelazez, A.; Abdelmotaal, H.; Zhu, Z.-T.; Fang-Fang, J.; Sami, R.; Zhang, L.-J.; Al-Tawaha, A.R.; Meng, X.-C. Potential Benefits of Lactobacillus plantarum as Probiotic and Its Advantages in Human Health and Industrial Applications: A Review 1. Adv. Environ. Biol. 2018, 12, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Almeida, A.P.; Neta, A.A.I.; de Andrade-Lima, M.; de Albuquerque, T.L. Plant-Based Probiotic Foods: Current State and Future Trends. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2024, 33, 3401–3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-Miguélez, J.M.; Martín, I.; González-Mohíno, A.; Souza Olegario, L.; Peromingo, B.; Delgado, J. Ultra-Processed Plant-Based Analogs: Addressing the Challenging Journey toward Health and Safety. J. Food Sci. 2024, 89, 10344–10362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erem, E.; Kilic-Akyilmaz, M. The Role of Fermentation with Lactic Acid Bacteria in Quality and Health Effects of Plant-Based Dairy Analogues. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2024, 23, e13402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhalis, H.; See, X.Y.; Osen, R.; Chin, X.H.; Chow, Y. The Potentials and Challenges of Using Fermentation to Improve the Sensory Quality of Plant-Based Meat Analogs. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1267227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawzi, N.Y.; Abdelghani, D.Y.; Abdel-azim, M.A.; Shokier, C.G.; Youssef, M.W.; Gad El-Rab, M.K.; Gad, A.I.; Abou-Taleb, K.A. The Ability of Probiotic Lactic Acid Bacteria to Ferment Egyptian Broken Rice Milk and Produce Rice-Based Yoghurt. Ann. Agric. Sci. 2022, 67, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, O.; Atalar, I.; Mortas, M.; Saricaoglu, F.T.; Besir, A.; Gul, L.B.; Yazici, F. Potential Use of High Pressure Homogenized Hazelnut Beverage for a Functional Yoghurt-like Product. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2022, 94, e20191172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, K.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, H.; Luo, D.K.; Yi, C.; Guan, X. Formulation of Plant-Based Yoghurt from Soybean and Quinoa and Evaluation of Physicochemical, Rheological, Sensory and Functional Properties. Food Biosci. 2022, 49, 101831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comak Gocer, E.M.; Koptagel, E. Production and Evaluation of Microbiological & Rheological Characteristics of Kefir Beverages Made from Nuts. Food Biosci. 2023, 52, 102367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masiá, C.; Jensen, P.E.; Petersen, I.L.; Buldo, P. Design of a Functional Pea Protein Matrix for Fermented Plant-Based Cheese. Foods 2022, 11, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Miguélez, J.M.; Martín, I.; Peromingo, B.; Delgado, J.; Córdoba, J.J. Pathogen and Spoilage Microorganisms in Meat and Dairy Analogues: Occurrence and Control Strategies. Foods 2025, 14, 1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, S.W.; Titgemeyer, F. Protective Cultures in Food Products: From Science to Market. Foods 2023, 12, 1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Miguélez, J.M.; Castaño, C.; Delgado, J.; Olegario, L.S.; González-Mohino, A. Protective Effect of Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Ripened Foods Against Listeria monocytogenes in Plant-Based Fermented Dry-Cured Sausages. Foods 2025, 14, 1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavelle, K.; Mahony, J.; van Sinderen, D. Adaptation of Bacterial Starter Cultures from Dairy to Plant-Based Substrates: Challenges and Opportunities. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2025, 441, 111304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijaya Kumar, B.; Vijayendra, S.V.N.; Reddy, O.V.S. Trends in Dairy and Non-Dairy Probiotic Products—A Review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 6112–6124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meruvu, H.; Harsa, S.T. Lactic acid bacteria: Isolation-characterization approaches and industrial applications. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 8337–8356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalighi, A.; Behdani, R.; Kouhestani, S.; Khalighi, A.; Behdani, R.; Kouhestani, S. Probiotics: A Comprehensive Review of Their Classification, Mode of Action and Role in Human Nutrition. In Probiotics and Prebiotics in Human Nutrition and Health; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinderola, G.; Ouwehand, A.C.; Salminen, S.; von Wright, A. Lactic Acid Bacteria: Microbiological and Functional Aspects; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019; pp. 1–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Singleton, S.S.; Bhuiyan, U.; Krammer, L.; Mazumder, R. Multi-Omics Approaches to Studying Gastrointestinal Microbiome in the Context of Precision Medicine and Machine Learning. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2023, 10, 1337373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, X.; Ed-Dra, A.; Yue, M. Whole Genome Sequencing for the Risk Assessment of Probiotic Lactic Acid Bacteria. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 11244–11262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukao, M.; Oki, A.; Segawa, S. Genome-Based Assessment of Safety Characteristics of Lacticaseibacillus paracasei NY1301 and Genomic Differences in Closely Related Strains Marketed as Probiotics. Biosci. Microbiota Food Health 2024, 43, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rychen, G.; Aquilina, G.; Azimonti, G.; Bampidis, V.; Bastos, M.d.L.; Bories, G.; Chesson, A.; Cocconcelli, P.S.; Flachowsky, G.; Gropp, J.; et al. Guidance on the Characterisation of Microorganisms Used as Feed Additives or as Production Organisms. EFSA J. 2018, 16, e05206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Wittouck, S.; Salvetti, E.; Franz, C.M.A.P.; Harris, H.M.B.; Mattarelli, P.; O’toole, P.W.; Pot, B.; Vandamme, P.; Walter, J.; et al. A Taxonomic Note on the Genus Lactobacillus: Description of 23 Novel Genera, Emended Description of the Genus Lactobacillus beijerinck 1901, and Union of Lactobacillaceae and Leuconostocaceae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 2782–2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingkaew, E.; Tanaka, N.; Shiwa, Y.; Sitdhipol, J.; Nuhwa, R.; Tanasupawat, S. Genomic Assessment of Potential Probiotic Lactiplantibacillus plantarum CRM56-2 Isolated from Fermented Tea Leaves. Trop. Life Sci. Res. 2024, 35, 249–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westermann, A.J.; Barquist, L.; Vogel, J. Resolving Host–Pathogen Interactions by Dual RNA-Seq. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siciliano, R.A.; Lippolis, R.; Mazzeo, M.F. Proteomics for the Investigation of Surface-Exposed Proteins in Probiotics. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäuerl, C.; Pérez-Martínez, G.; Yan, F.; Polk, D.B.; Monedero, V. Functional Analysis of the P40 and P75 Proteins from Lactobacillus casei BL23. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 19, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Sagardía, M.; Cabezón, E.C.; Delgado, J.; Ruiz-Moyano, S.; Garrido, D. Screening Microbial Interactions During Inulin Utilization Reveals Strong Competition and Proteomic Changes in Lacticaseibacillus paracasei M38. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2024, 16, 993–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vega-Sagardía, M.; Delgado, J.; Ruiz-Moyano, S.; Garrido, D. Proteomic Analyses of Bacteroides ovatus and Bifidobacterium longum in Xylan Bidirectional Culture Shows Sugar Cross-Feeding Interactions. Food Res. Int. 2023, 170, 113025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez, B.; Delgado, S.; Blanco-Míguez, A.; Lourenço, A.; Gueimonde, M.; Margolles, A. Probiotics, Gut Microbiota, and Their Influence on Host Health and Disease. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61, 1600240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fusco, W.; Lorenzo, M.B.; Cintoni, M.; Porcari, S.; Rinninella, E.; Kaitsas, F.; Lener, E.; Mele, M.C.; Gasbarrini, A.; Collado, M.C.; et al. Short-Chain Fatty-Acid-Producing Bacteria: Key Components of the Human Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telbisz, Á.; Homolya, L. Recent Advances in the Exploration of the Bile Salt Export Pump (BSEP/ABCB11) Function. Expert. Opin. Ther. Targets 2016, 20, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Montoro, B.; Benomar, N.; Caballero Gómez, N.; Ennahar, S.; Horvatovich, P.; Knapp, C.W.; Alonso, E.; Gálvez, A.; Abriouel, H. Proteomic Analysis of Lactobacillus Pentosus for the Identification of Potential Markers of Adhesion and Other Probiotic Features. Food Res. Int. 2018, 111, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stastna, M. The Role of Proteomics in Identification of Key Proteins of Bacterial Cells with Focus on Probiotic Bacteria. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, V.; Velumani, D.; Lin, Y.C.; Haye, A. A Comprehensive Review of Probiotic Claims Regulations: Updates from Asia-Pacific, United States, and Europe. PharmaNutrition 2024, 30, 100423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Comission Regulation (EC). No 178/2002 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 28 January 2002 Laying down the General Principles and Requirements of Food Law, Establishing the European Food Safety Authority and Laying down Procedures in Matters of Food Safety. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2002/178/oj (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- European Comission Regulation (EC). No 852/2004 (as Amended) of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 on the Hygiene of Foodstuffs. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32004R0852&qid=1684830922214 (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Food Safety Authority of Ireland. Assessment of the Safety of “Probiotics” in Food Supplements; Food Safety Authority of Ireland: Dublin, Ireland, 2024; ISBN 9781910348765. [Google Scholar]

- EFSA Qualified Presumption of Safety (QPS). Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/topics/topic/qualified-presumption-safety-qps#efsa’s-role (accessed on 28 November 2025).

| Target Gene | Encoded Protein | Primer Sequence (5′–3′) | Annealing Temperature (°C) | Amplified Size (bp) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gelE | Gelatinase | F-TATGACAATGCTTTTTGGGAT R-AGATGCACCCGAAATAATATA | 47 | 213 | [86] |

| cylA | Cytolisin | F-ACTCGGGGATTGATAGGC GCTGCTAAAGCTGCGCTT | 52 | 688 | [86] |

| hyl | Hyaluronidase | F-ACAGAAGAGCTGCAGGAAATG R-GACTGACGTCCAAGTTTCCAA | 53 | 276 | [86] |

| asa1 | Aggregation substance | F-GCACGCTATTACGAACTATGA R-TAAGAAAGAACATCACCACGA | 50 | 375 | [86] |

| esp | Enterococcal surface | F-AGATTTCATCTTTGATTCTTG R-AATTGATTCTTTAGCATCTGG | 47 | 510 | [86] |

| efaA | Endocarditis antigen | F-GCCAATTGGGACAGACCCTC R-CGCCTTCTGTTCCTTCTTTGGC | 57 | 688 | [86] |

| ace | Adhesion of collagen | F-GAATTGAGCAAAAGTTCAATCG R-GTCTGTCTTTTCACTTGTTTC | 48 | 1008 | [86] |

| hdc1 | Histidine decarboxylase | F-AGATGGTATTGTTTCTTATG R-AGACCATACACCATAACCTT | 46 | 367 | [86] |

| odc | Ornithine decarboxylase | F-GTNTTYAAYGCNGAYAARCANTAYTTYGT R-ATNGARTTNAGTTCRCAYTTYTCNGG | 54 | 1446 | [86] |

| tdc | Tyrosine decarboxylase | F-GAYATNATNGGNATNGGNYTNGAYCARG R-CCRTARTCNGGNATAGCRAARTCNGTRTG | 55 | 924 | [86] |

| tdc2 | Tyrosine decarboxylase | F-AAYTCNTTYGAYTTYGARAARGARG R-ATNGGNGANCCDATCATYTTRTGNCC | 50 | 534 | [86] |

| ccf | Sex pheromones | F-GGGAATTGAGTAGTGAAGAAG R-AGCCGCTAAAATCGGTAAAAT | 51 | 543 | [87] |

| vanA | Vancomycin resistance | F-TCTGCAATAGAGATAGCCGC R-GGAGTAGCTATCCCAGCATT | 52 | 377 | [88] |

| vanB | Vancomycin resistance | F-GCTCCGCAGCCTGCATGGACA R-ACGATGCCGCCATCCTCCTGC | 60 | 529 | [88] |

| aphA-1 | Aminoglycoside resistance | F-ATGGGCTCGCGATAATGTC R-CTCACCGAGGCAGTTCCAT | 56 | 600 | [89] |

| blaIMP | β-Lactams resistance | F-CTACCGCAGCAGAGTCTTTG R-AACCAGTTTTGCCTTACCAT | 53 | 587 | [89] |

| gyrA | Quinolones resistance | F-TTCTCCGATTTCCTCATG R-AGAAGGGTACGAATGTGG | 49 | 458 | [89] |

| ermA/TR | Macrolides resistance | F-TCAGGAAAAGGACATTTTACC R-ATACTTTTTGTAGTCCTTCTT | 46 | 432 | [89] |

| rpsL | Streptomycin resistance | F-GGCCGACAAACAGAACGT R-GTTCACCAACTGGGTGAC | 54 | 501 | [89] |

| tetA | Tetracyclines resistance | F-GTAATTCTGAGCACTGTCGC R-CTGCCTGGACAACATTGCTT | 54 | 937 | [89] |

| Target Gene | Encoded Protein | Primer Sequence (5′–3′) | Annealing Temperature (°C) | Amplified Size (bp) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| groEL | Heat shock protein 60 | F-TTCCATGGCkTCAGCrATCA R-GCTAAyCCwGTTGGCATTCG | 58 | 168 | [99] |

| LBA 1272 | Cyclopropane FA | F-GGCTTACCAATGGCCACCTT R-GATCAAAAAGCCGGTCACGA | 57.5 | 210 | [94] |

| LBA 1446 | Multidrug resistance | F-GCTGGAGCCACACCGATAAC R-CAACGGGATTATGATTCCCATTAGT | 58 | 275 | [94] |

| bsh | Conjugated bile salt acid hydrolase | F-ATTCCWTGGWTWYTGGGACA R-AAAAGCRGCTCTNACAAAWCKAGA | 58 | 384 | [94] |

| clpL | ATPase synthase | F-GCTGCCTTyAAAACATCATCTGG R-AATACAATTTTGAArAACGCAGCTT | 56 | 158 | [94] |

| LAB Strain | Food Source | Main Probiotic Effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lactiplantibacillus plantarum 299v | Fermented vegetables/cereals | Gut colonization, modulation of microbiota, immunomodulation, cholesterol-lowering | [107,110] |

| Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus GG | Fermented milk (yoghurt, cheese) | Survival in GIT, pathogen inhibition, immune modulation, clinical validation | [71,107] |

| Levilactobacillus brevis MK05 | Fermented meat (sausages) | Antioxidant activity, bile tolerance, antimicrobial activity | [107] |

| Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis | Traditional dairy products | Immune stimulation, antimicrobial effects, technological suitability as a starter culture | [105] |

| Limosilactobacillus fermentum ME-3 | Cocoa fermentation | Antioxidant properties, cholesterol-lowering, gut protection | [107] |

| Pediococcus acidilactici VKU2 | Traditional cereal-dairy product (Tarkhineh, Iran) | Cholesterol removal, antioxidant activity, survival under acidic conditions | [105] |

| Leuconostoc mesenteroides | Kimchi, sauerkraut, vegetable fermentations | Exopolysaccharide production, antioxidant activity, gut microbiota modulation | [104] |

| Microbial Strain | Plant-Based Substrate | Plant Source | Fermentation Effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus; Streptococcus thermophilus; Lactiplantibacillus plantarum; Lacticaseibacillus casei; Lactobacillus acidophilus; Bifidobacterium | Fermented “yogurt-like” analogue | Soybean; rice; hazelnut | Increased antioxidant capacity and enhanced digestive enzyme inhibition through fermentation. Elevated vitamin B6 and B1 concentrations following fermentation | [115,116,117] |

| Kefir culture | Kefir analogue | Almond; peanut; hazelnut; walnut; cashew | Titratable acid reduction, prebiotic Fibre supporting probiotic viability | [118] |

| Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lacticaseibacillus paracasei, and Bifidobacterium | Cheese analogue | Pea protein isolate | Fermentation did not affect the characteristics of the final product | [119] |

| Lactiplantibacillus plantarum; Leuconostoc mesenteroides | Vegetable fermentations/analogues | Mixed vegetables | High LAB counts, production of organic acids and bioactives, antioxidant enhancement | [54] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martín-Miguélez, J.M.; Peromingo, B.; Castaño, C.; Córdoba, J.J.; Delgado, J.; Martín, I. Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Traditional Dry-Cured Fermented Foods with Probiotic Effect: Selection, Mechanisms of Action and Applications. Foods 2025, 14, 4332. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244332

Martín-Miguélez JM, Peromingo B, Castaño C, Córdoba JJ, Delgado J, Martín I. Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Traditional Dry-Cured Fermented Foods with Probiotic Effect: Selection, Mechanisms of Action and Applications. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4332. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244332

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartín-Miguélez, José M., Belén Peromingo, Cristina Castaño, Juan J. Córdoba, Josué Delgado, and Irene Martín. 2025. "Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Traditional Dry-Cured Fermented Foods with Probiotic Effect: Selection, Mechanisms of Action and Applications" Foods 14, no. 24: 4332. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244332

APA StyleMartín-Miguélez, J. M., Peromingo, B., Castaño, C., Córdoba, J. J., Delgado, J., & Martín, I. (2025). Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Traditional Dry-Cured Fermented Foods with Probiotic Effect: Selection, Mechanisms of Action and Applications. Foods, 14(24), 4332. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244332