clpC-Mediated Translational Control Orchestrates Stress Tolerance and Biofilm Formation in Milk-Originated Staphylococcus aureus RMSA24

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strain

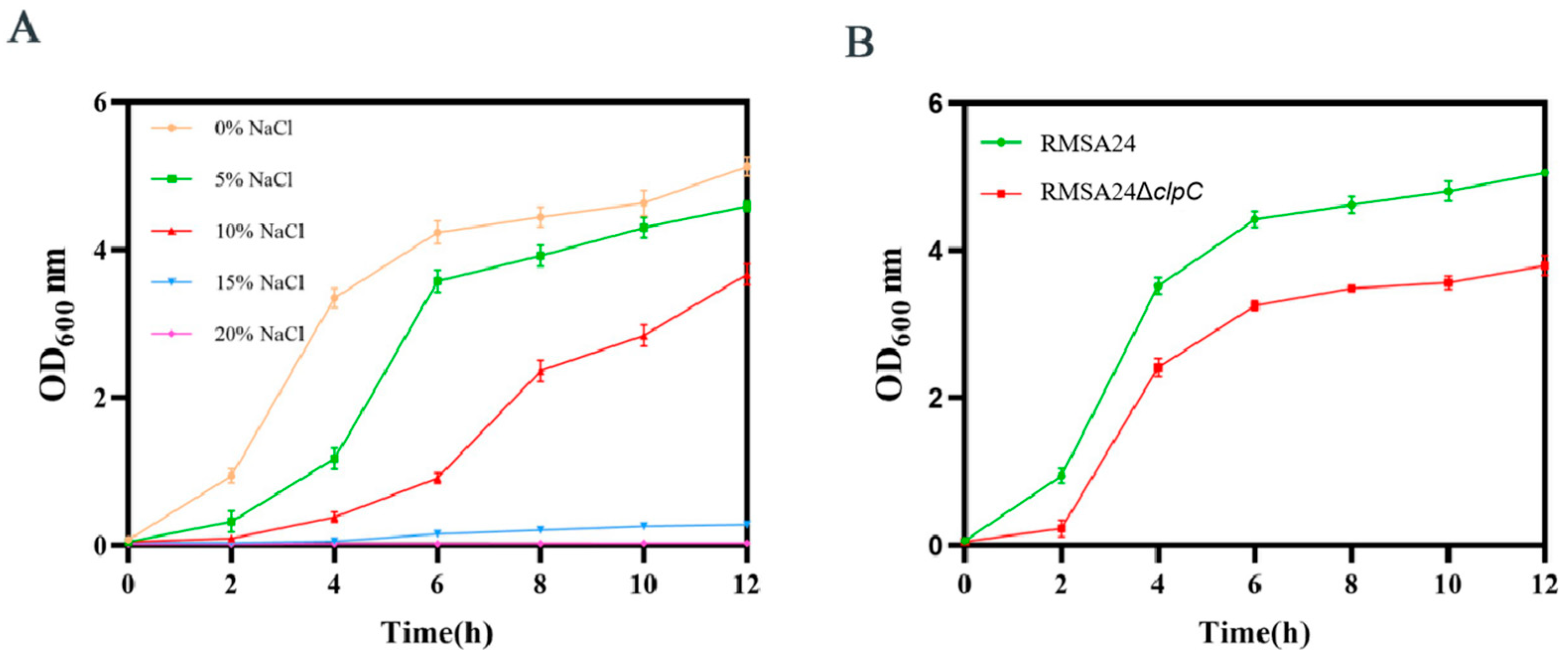

2.2. Construction of the clpC-Deficient Mutant and Growth Curve Analysis

2.3. Desiccation Survival Assay

2.4. High-Temperature Survival Assay

2.5. H2O2 Pressure Survival Assay

2.6. High-Osmotic Pressure Survival Assay

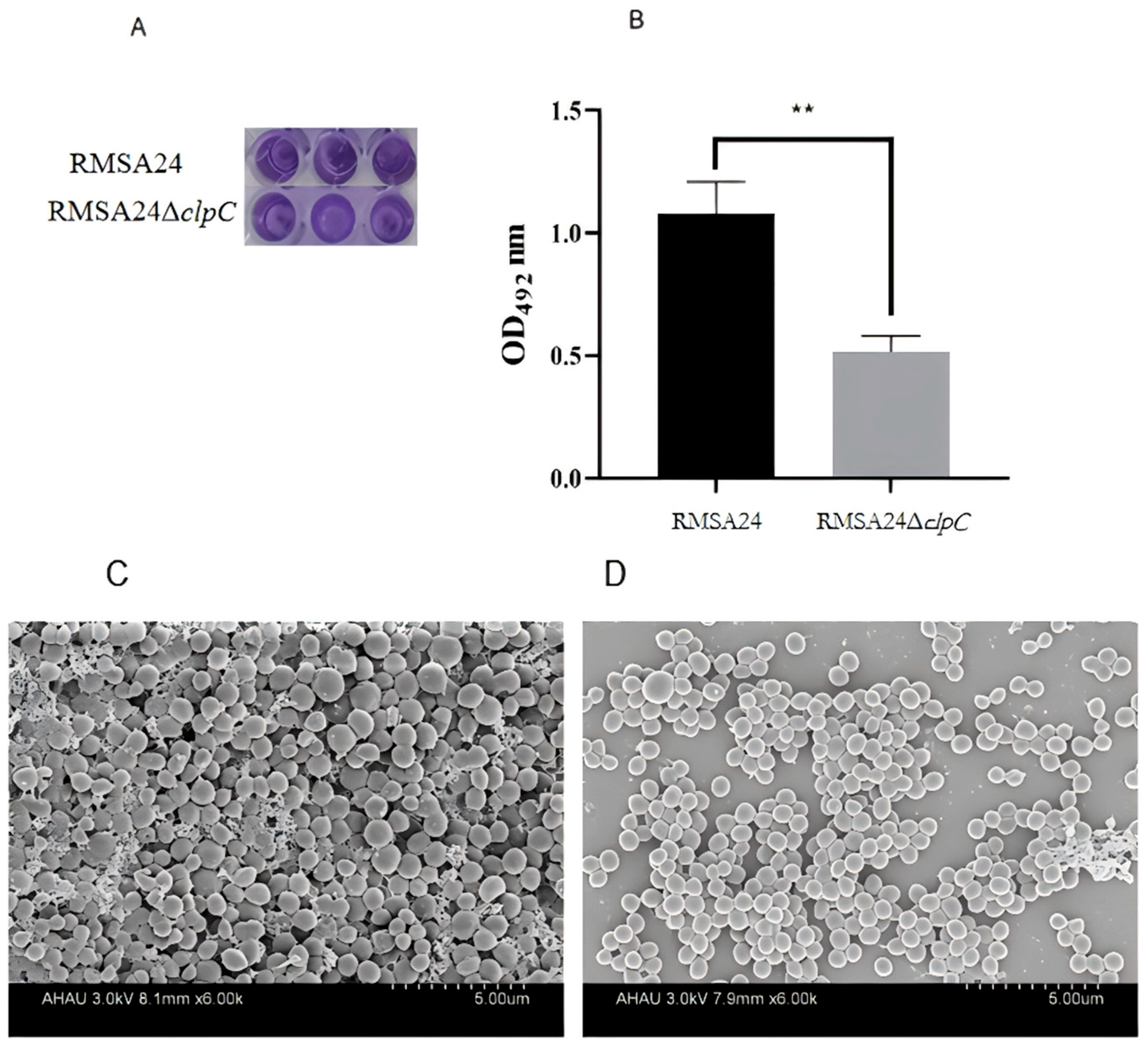

2.7. Biofilm Formation

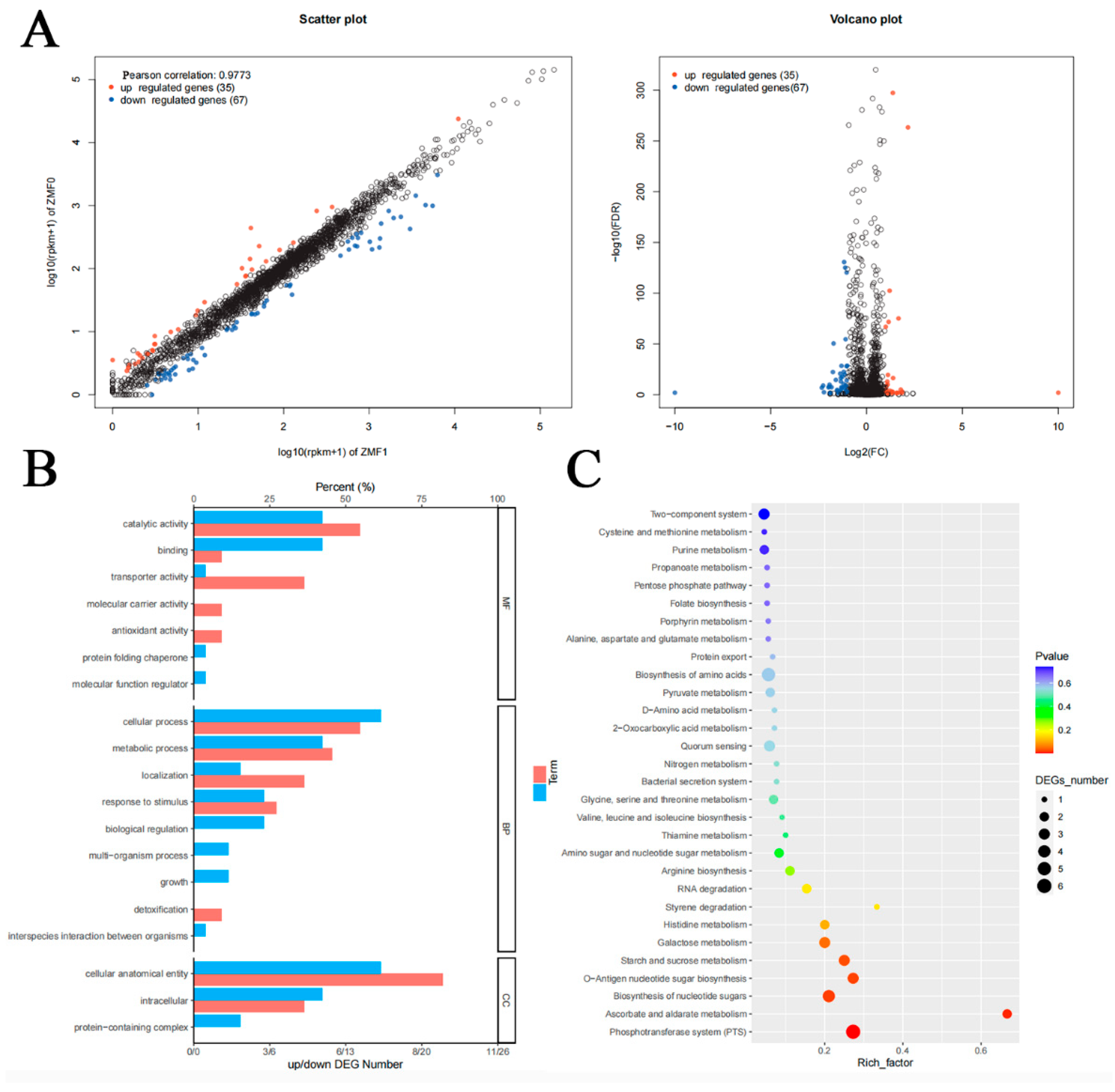

2.8. Transcriptome Analysis

3. Results

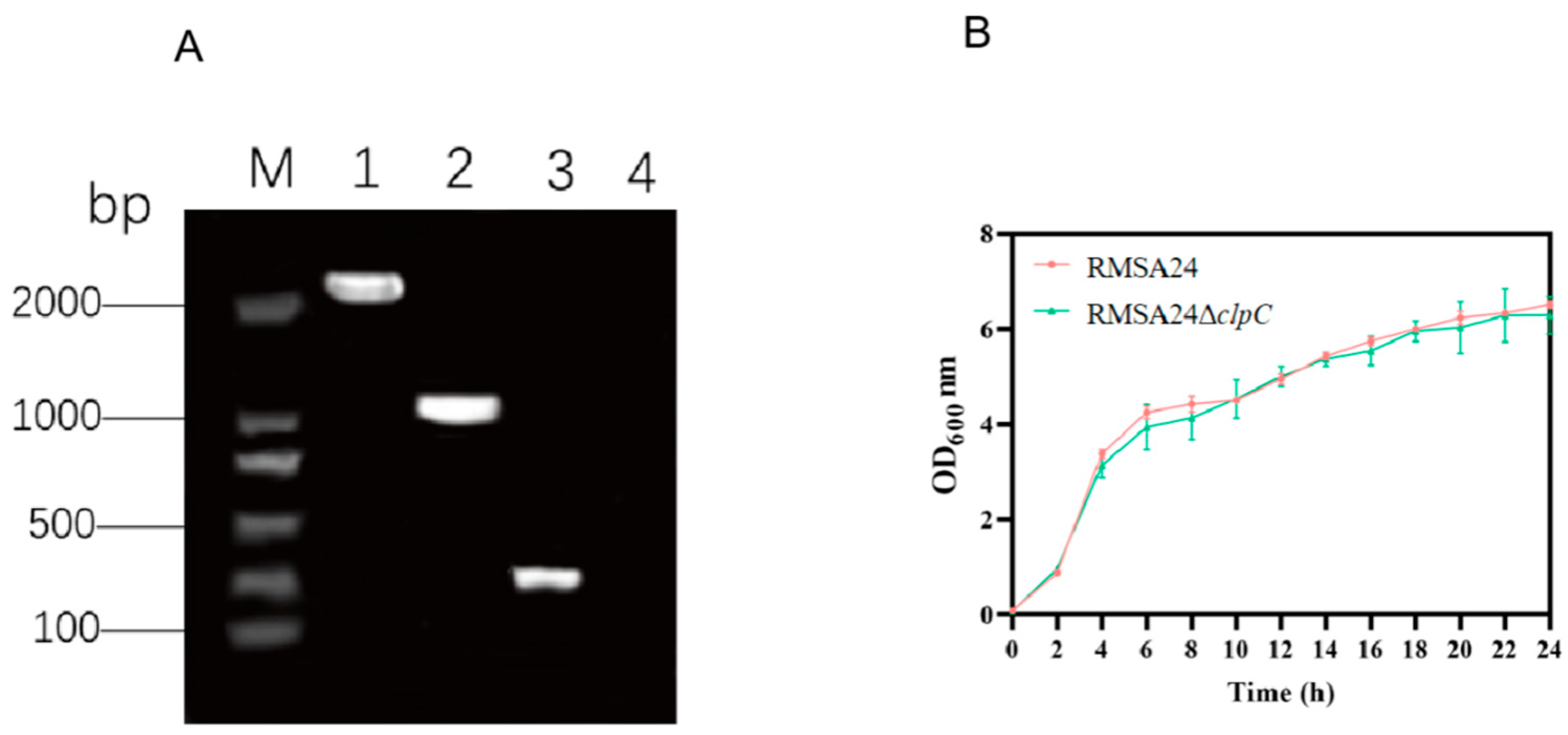

3.1. Construction of clpC Knockout Strain

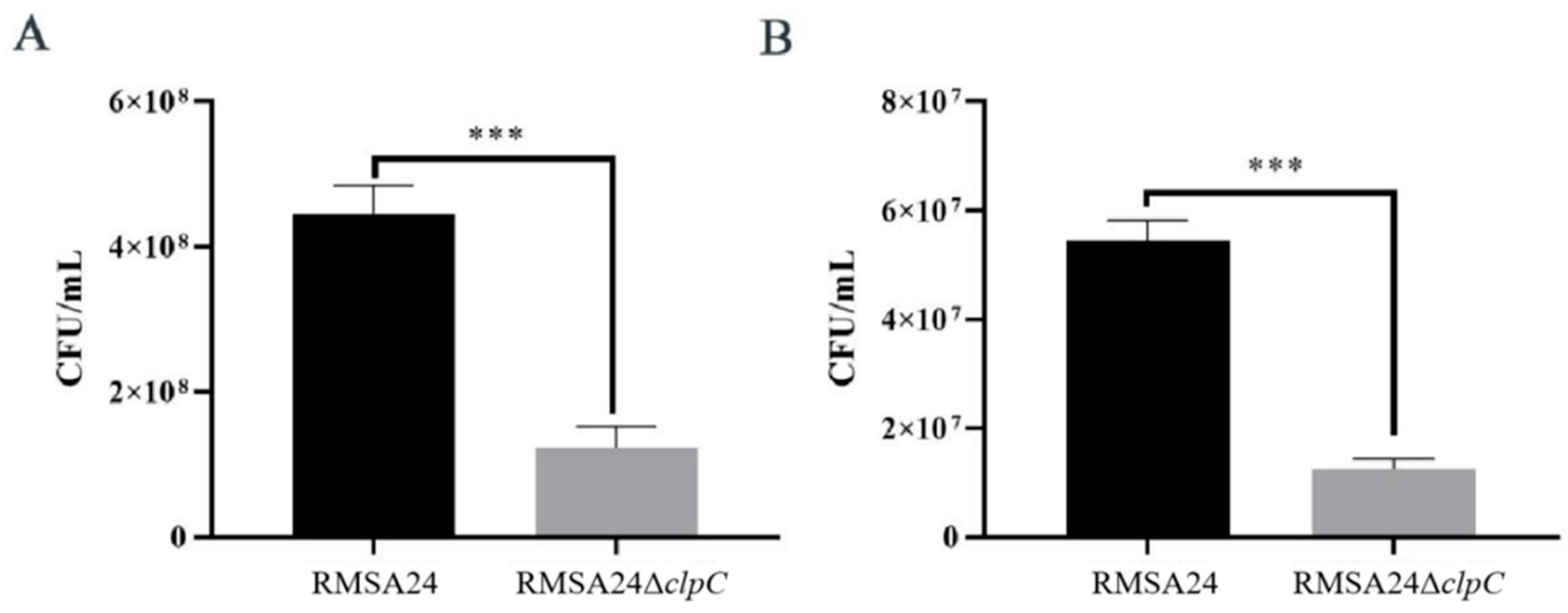

3.2. Effect of clpC Knockout on Desiccation Tolerance in RMSA24

3.3. Effect of clpC Knockout on Thermotolerance in RMSA24

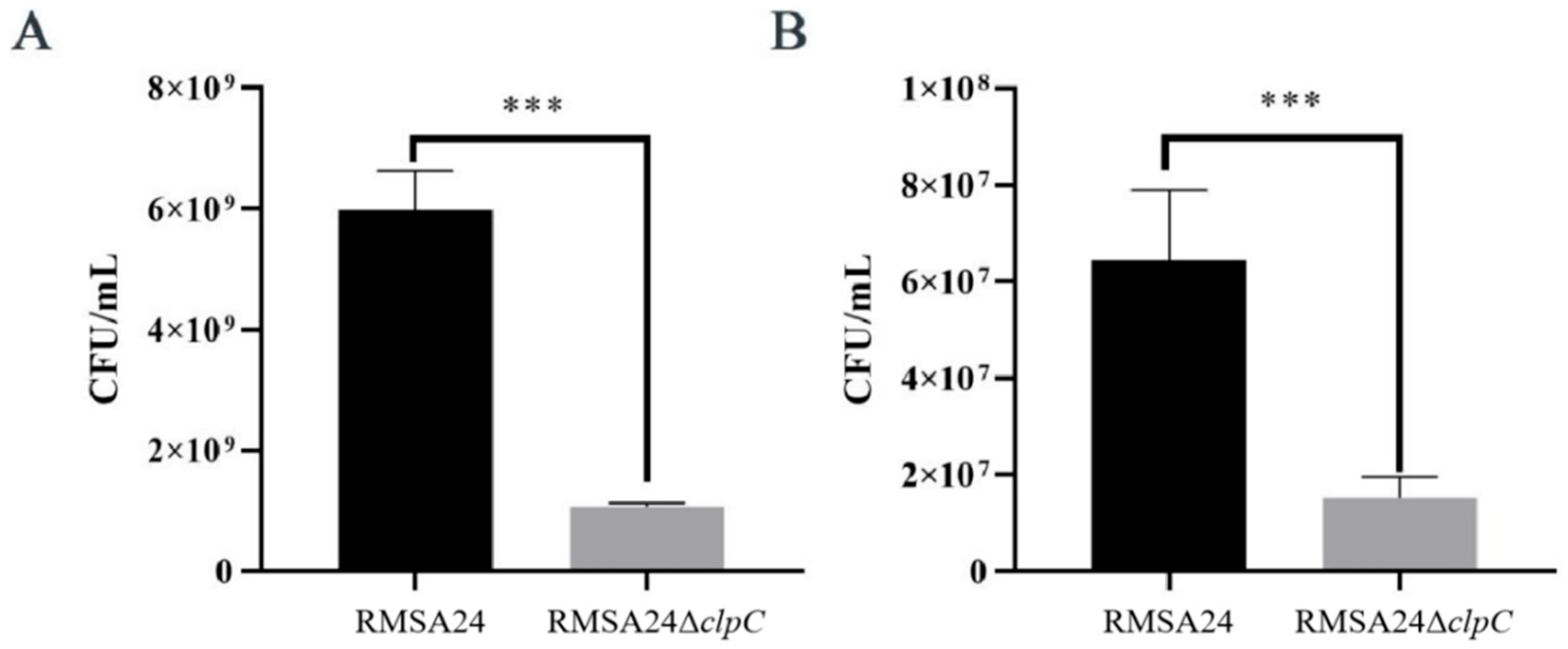

3.4. Effect of clpC Knockout on Oxidative Stress Resistance in RMSA24

3.5. Effect of clpC Knockout on Hyperosmotic Stress Tolerance in RMSA24

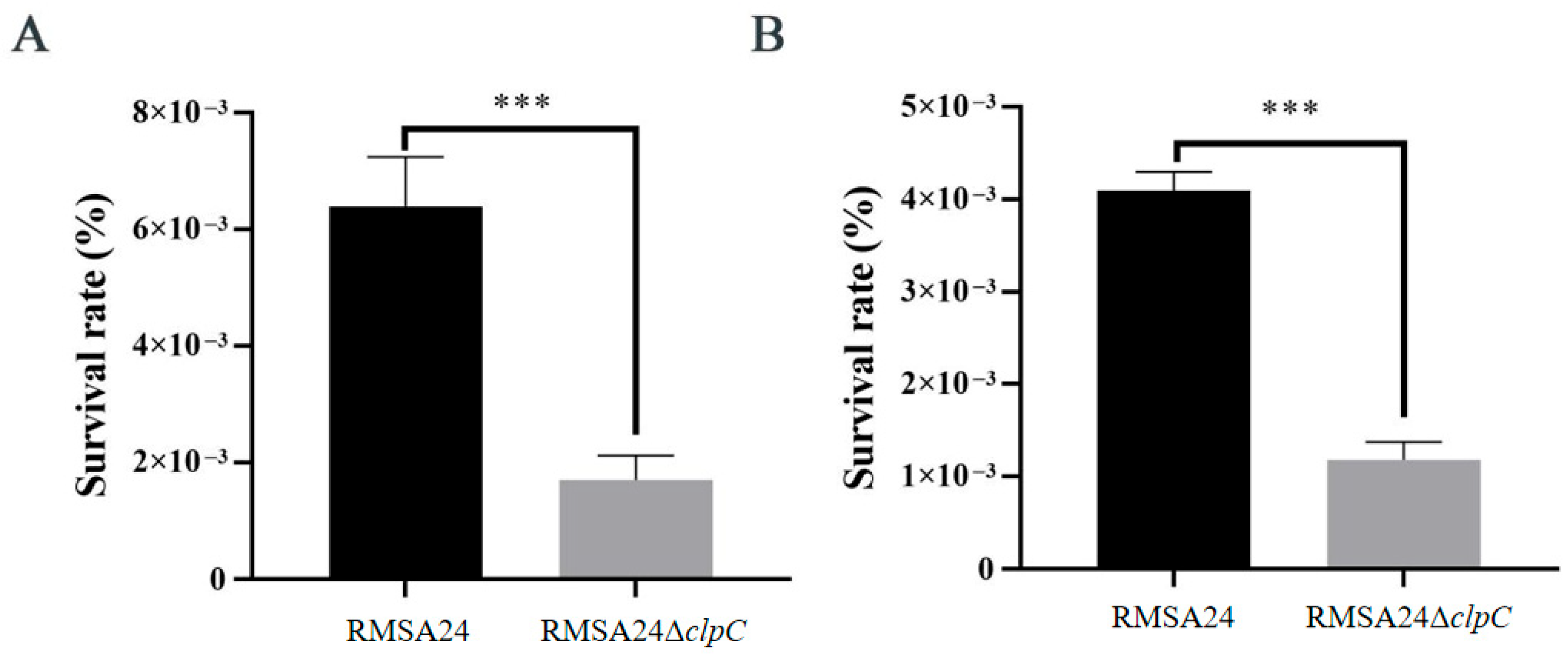

3.6. Effect of clpC Knockout on Biofilm Formation in RMSA24

3.7. Transcriptomic Analysis of clpC Knockout in RMSA24

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Costa, F.G.; Mills, K.B.; Crosby, H.A.; Horswill, A.R. The Staphylococcus aureus regulatory program in a human skin-like environment. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Machado, C.; Capita, R.; Alonso-Calleja, C. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in dairy products and bulk-tank milk (BTM). Antibiotics 2024, 13, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debeer, J.; Colley, J.; Cole, W.; Oliveira, A.; Waite-Cusic, J.; Soto, W. Staphylococcus aureus burden in frozen, precooked tuna loins and growth behavior during typical and “worst-case” processing Conditions. J. Food Prot. 2025, 88, 100539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasela, M.; Ossowski, M.; Dzikoń, E.; Ignatiuk, K.; Wlazo, U.; Malm, A. The epidemiology of animal-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Machado, C.; Alonso-Calleja, C.; Capita, R. Prevalence and types of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in meat and meat products from retail outlets and in samples of animal origin collected in farms, slaughterhouses and meat processing facilities. A review. Food Microbiol. 2024, 123, 104580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freitas, R.G.K.J.; Assis, D.F.C.; Oliveira, D.M.R.T. Global prevalence of staphylococcal enterotoxins in food contaminated by Staphylococcus spp.—Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Food Saf. 2024, 44, e13154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiawei, S.; Hui, W.; Chengfeng, Z. Effect of biofilm on the survival of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from raw milk in high temperature and drying environment. Food Res. Int. 2021, 149, 110672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, J.K.G.R.; Assis, C.F.D.; Oliveira, T.R.M.D. Prevalence of staphylococcal toxin in food contaminated by Staphylococcus spp.: Protocol for a systematic review with meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0282111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starkova, D.; Gladyshev, N.; Polev, D. First insight into the whole genome sequence variations in clarithromycin resistant Helicobacter pylori clinical isolates in Russia. Sci. Rep. 2025, 14, 20108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuwald, A.F.; Aravind, L.; Spounge, J.L.; Koonin, E.V. AAA+: A class of chaperone-like ATPases associated with the assembly, operation, and disassembly of protein complexes. Genome Res. 1999, 9, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandi, A.; Giangrossi, M.; Paoloni, S.; Spurio, R.; Giuliodori, A.; Pon, C. Transcriptional and post-transcriptional events trigger de novo infB expression in cold stressed Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 4638–4651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Hou, X.; Shen, J.; Wang, W.; Ye, Y.; Yu, J. Alternative sigma factor B reduces biofilm formation and stress response in milk-derived Staphylococcus aureus. LWT 2022, 162, 113515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chastanet, A.; Derré, I.; Nair, S.; Msadek, T. clpB, a novel member of the Listeria monocytogenes CtsR regulon, is involved in virulence but not in general stress tolerance. Bacteriology 2004, 186, 1165–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, A.K. Variations on a theme: Combined molecular chaperone and proteolysis functions in Clp/HSP1000 proteins. J. Biosci. 1996, 21, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porankiewicz, J.; Wang, J.; Clarke, A.K. New insights into the ATP-dependent Clp protease: Escherichia coli and beyond. Mol. Microbiol. 1999, 32, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frees, D.; Chastanet, A.; Qazi, S.; Sørensen, K.; Hill, P.; Msadek, T.; Ingmer, H. Clp ATPases are required for stress tolerance, intracellular replication and biofilm formation in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 2004, 54, 1445–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donegan, N.P.; Thompson, E.T.; Fu, Z.; Cheung, A.L. Proteolytic regulation of toxin-antitoxin systems by ClpPC in Staphylococcus aureus. Bacteriology 2010, 192, 1416–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frees, D.; Sørensen, K.; Ingmer, H. Global virulence regulation in Staphylococcus aureus: Pinpointing the roles of ClpP and ClpX in the sar/agr regulatory network. Infect. Immun. 2005, 73, 8100–8108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, H.; Zhu, C.; Shu, F.; Lu, Z.; Wang, H.; Ma, K.; Wang, J.; Lan, R.; Shang, F.; Xue, T. Cody: An essential transcriptional regulator involved in environmental stress tolerance in foodborne Staphylococcu saureus rmsa24. Foods 2023, 12, 3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.A.H.; Maharik, N.M.S.; Valero, A.; Kamal, S.M. Incidence of enterotoxigenic Staphylococcus aureus in milk and egyptian artisanal dairy products. Food Control 2019, 104, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecker, M.; Schumann, W.; Volker, U. Heat-shock and general stress response in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 1996, 19, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cebrian, G.; Sagarzazu, N.; Pagan, R.; Condon, S.; Manas, P. Development of stress resistance in Staphylococcus aureus after exposure to sublethal environmental conditions. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2010, 140, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celano, B.; Pawlik, R.T.; Gualerzi, C.O. Interaction of Escherichia coli translation-initiation factor IF-1 with ribosomes. FEBS J. 2010, 178, 351–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visioli, F.; Strata, A. Milk, dairy products, and their functional effects in humans: A narrative review of recent evidence. Adv. Nutr. 2014, 5, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowy, F.D. Staphylococcus aureus Infections. N. Engl. Med. 1998, 339, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, L.; He, J. Biofflms: The microbial “protective clothing” in extreme environments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Tong, Y.; Cheng, J.; Abbas, Z.; Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Si, D.; Zhang, R. Biofilm and small colony variants—An Update on Staphylococcus aureus strategies toward drug resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisa, M.; Yuri, U.; Kazuya, M. Fitness of spontaneous rifampicin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates in a biofilm environment. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asao, T.; Kumeda, Y.; Kawai, T.; Shibata, T.; Oda, H.; Haruki, K.; Nakazawa, H.; Kozaki, S. An extensive outbreak of staphylococcal food poisoning due to low-fat milk in Japan: Estimation of enterotoxin A in the incriminated milk and powdered skim milk. Epidemiol. Infect. 2003, 130, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadat, A.; Shata, R.R.; Farag, A.M.; Ramadan, H.; Alkhedaide, A.; Soliman, M.M.; Elbadawy, M.; Abugomaa, A.; Awad, A. Prevalence and characterization of PVL-Positive Staphylococcus aureus isolated from Raw Cow’s Milk. Toxins 2022, 14, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Zheng, W.; Wang, X. A novel hydrophobic peptide FGMp11: Insights into antimicrobial properties, hydrophobic sites on Staphylococcus aureus and its application in infecting pasteurized milk. Food Chem. Adv. 2024, 4, 100697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, A.; Agerer, F.; Hauck, C.R. Global regulatory impact of ClpP Protease of Staphylococcus aureus on regulons involved in virulence, oxidative stress response, autolysis, and DNA repair. J. Bacteriol. 2006, 188, 5783–5796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maudsdotter, L.; Imai, S.; Ohniwa, R.L.; Saito, S.; Morikawa, K. Staphylococcus aureus dry stress survivors have a heritable fitness advantage in subsequent dry exposure. Microbes Infect. 2015, 17, 456–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beavers, W.N.; Skaar, E.P. Neutrophil-generated oxidative stress and protein damage in Staphylococcus aureus. Pathog. Dis. 2016, 74, ftw060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebrián, G.; Sagarzazu, N.; Aertsen, A.; Pagán, R.; Condón, S.; Mañas, P. Role of the alternative sigma factor sigma on Staphylococcus aureus resistance to stresses of relevance to food preservation. Appl. Microbiol. 2009, 107, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Strains | Details | Reference or Source |

|---|---|---|

| S. aureus | ||

| RMSA24 | WT | Milk |

| RN4200 | 8325-4, restriction-negative strain | NARSA |

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | Clone host strain, supE44 ΔlacU169(φ80 lacZΔM15) hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1relA1 | Invitrogen (Waltham, MA, USA) |

| Plasmids | ||

| pEC1 | pBluescript derivative. Source of ermB gene, Ampr | Research group |

| pBT2 | shuttle vector, temperature sensitive, Ampr, Cmr | Research group |

| pBT-clpC | pBT2 derivative, for clpC mutagenesis; Ampr, Cmr, Emr | This study |

| Primer Name | Oligonucleotide (5′–3′) |

|---|---|

| clpC-up HindIII-F | GCGAAGCTTTAACGCTTAATTGCTCA |

| clpC-up-R | GAAATTCCAGTCATGCAAGTGGTCA |

| clpC-ErmB-F | CATAAGCGAAATAGATTTAAAATTTCGC |

| clpC-ErmB-R | TGAAGTGTGGATACCATGCAAGTGGTCA |

| clpC-down-F | AGGATTCGGATTCAATGGCTCT |

| clpC-down BamHI-R | GCGGGATCCACCGCTATACTCTTCGC |

| check-pBT2-F | TCACCGACAAACAACAGA |

| check-pBT2-R | CCAAGCCTATGCCTACA |

| check-clpC-in-F | GAACGGAAGTTTGAAGCC |

| check-clpC-in-R | TAAACCGATACGCTCACC |

| check-clpC-out-F | GTAGGTGCAGTTCGATTTCAGG |

| check-clpC-out-R | AAAAAGAAGCTGGTTCAGCTCT |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, M.; Hu, J.; Xue, T. clpC-Mediated Translational Control Orchestrates Stress Tolerance and Biofilm Formation in Milk-Originated Staphylococcus aureus RMSA24. Foods 2025, 14, 4333. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244333

Zhang M, Hu J, Xue T. clpC-Mediated Translational Control Orchestrates Stress Tolerance and Biofilm Formation in Milk-Originated Staphylococcus aureus RMSA24. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4333. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244333

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Maofeng, Jie Hu, and Ting Xue. 2025. "clpC-Mediated Translational Control Orchestrates Stress Tolerance and Biofilm Formation in Milk-Originated Staphylococcus aureus RMSA24" Foods 14, no. 24: 4333. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244333

APA StyleZhang, M., Hu, J., & Xue, T. (2025). clpC-Mediated Translational Control Orchestrates Stress Tolerance and Biofilm Formation in Milk-Originated Staphylococcus aureus RMSA24. Foods, 14(24), 4333. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244333