Implementation of Instrumental Analytical Methods, Image Analysis and Chemometrics for the Comparative Evaluation of Citrus Fruit Peels

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling and Lyophilization

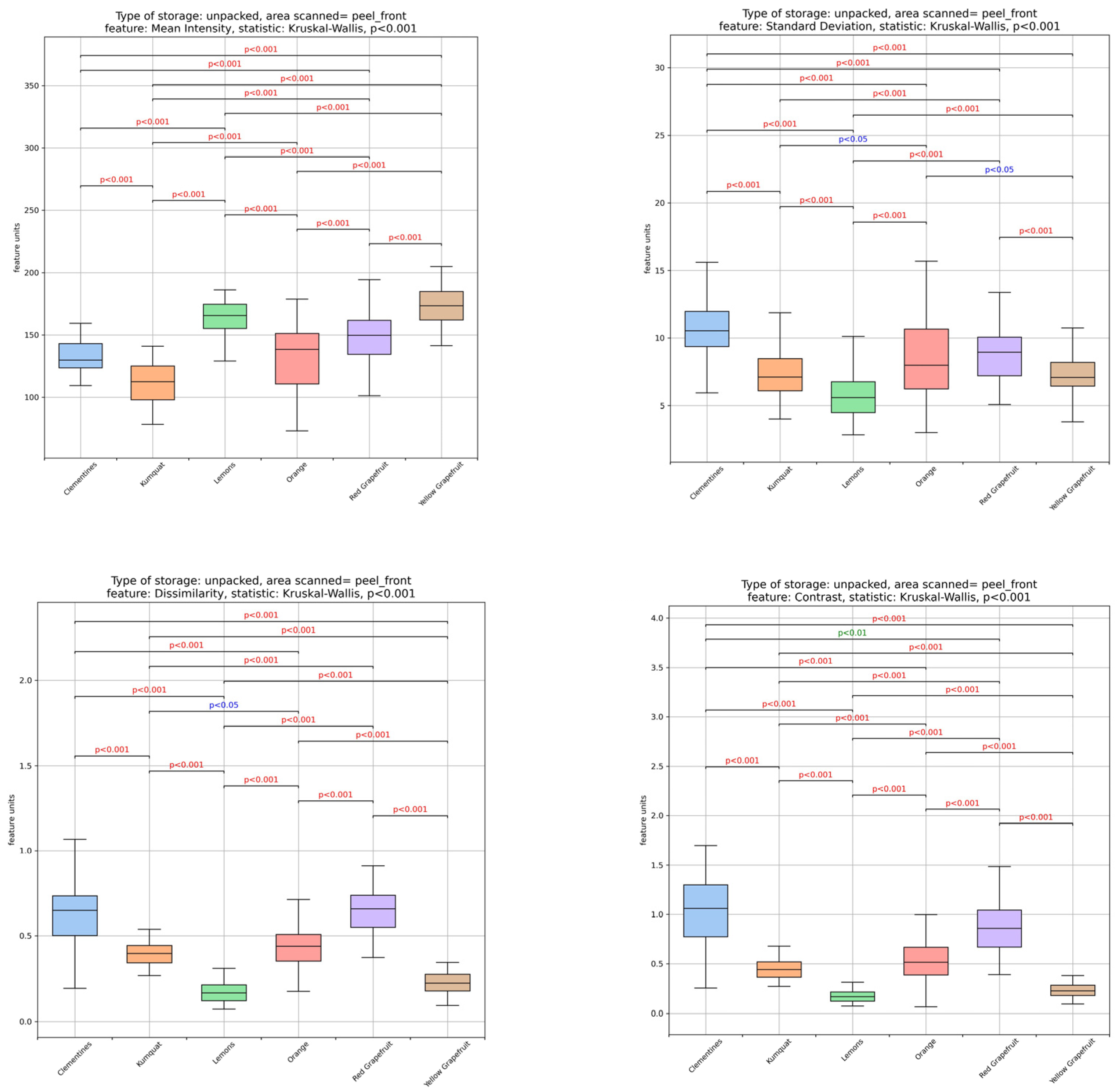

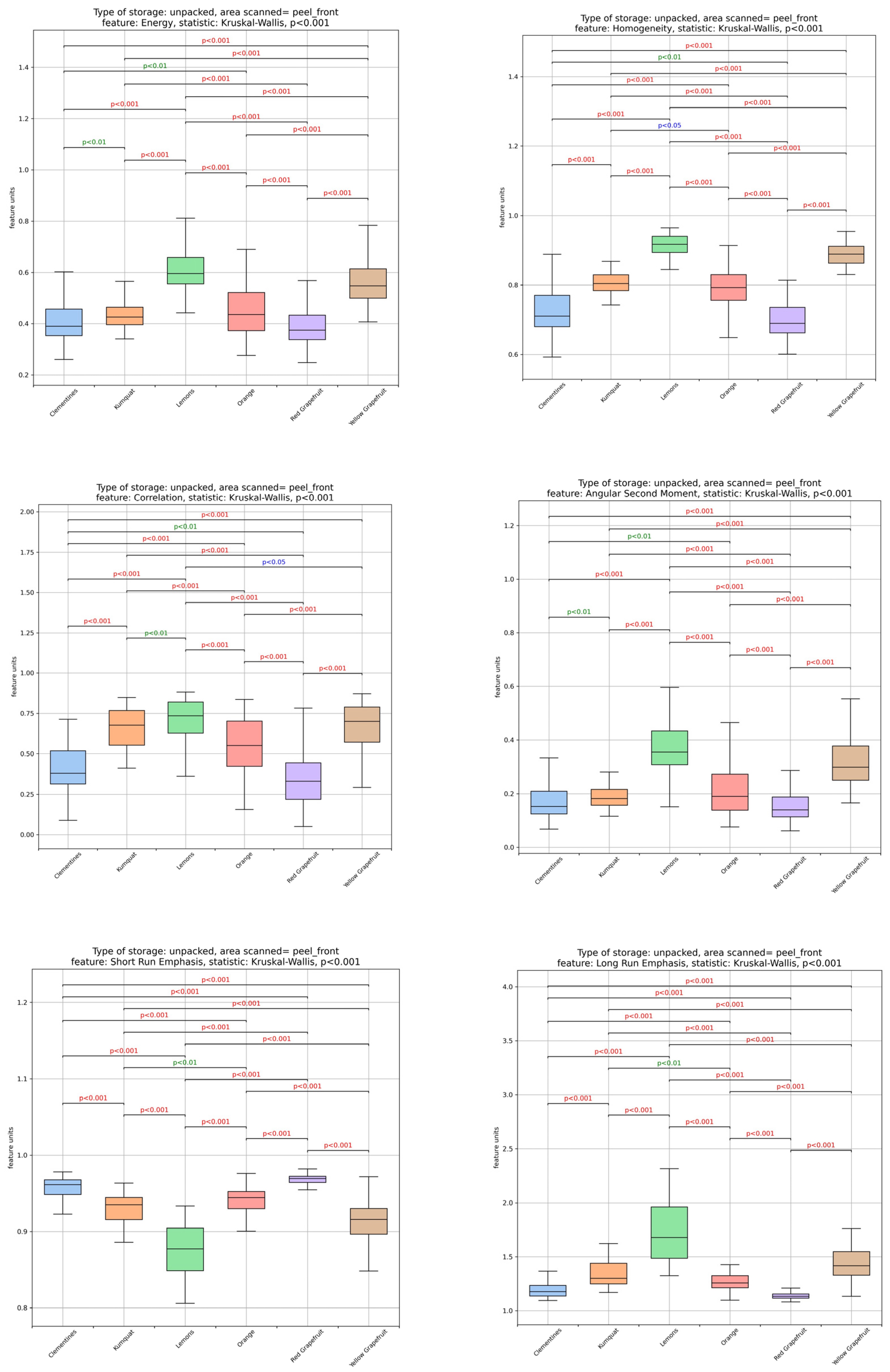

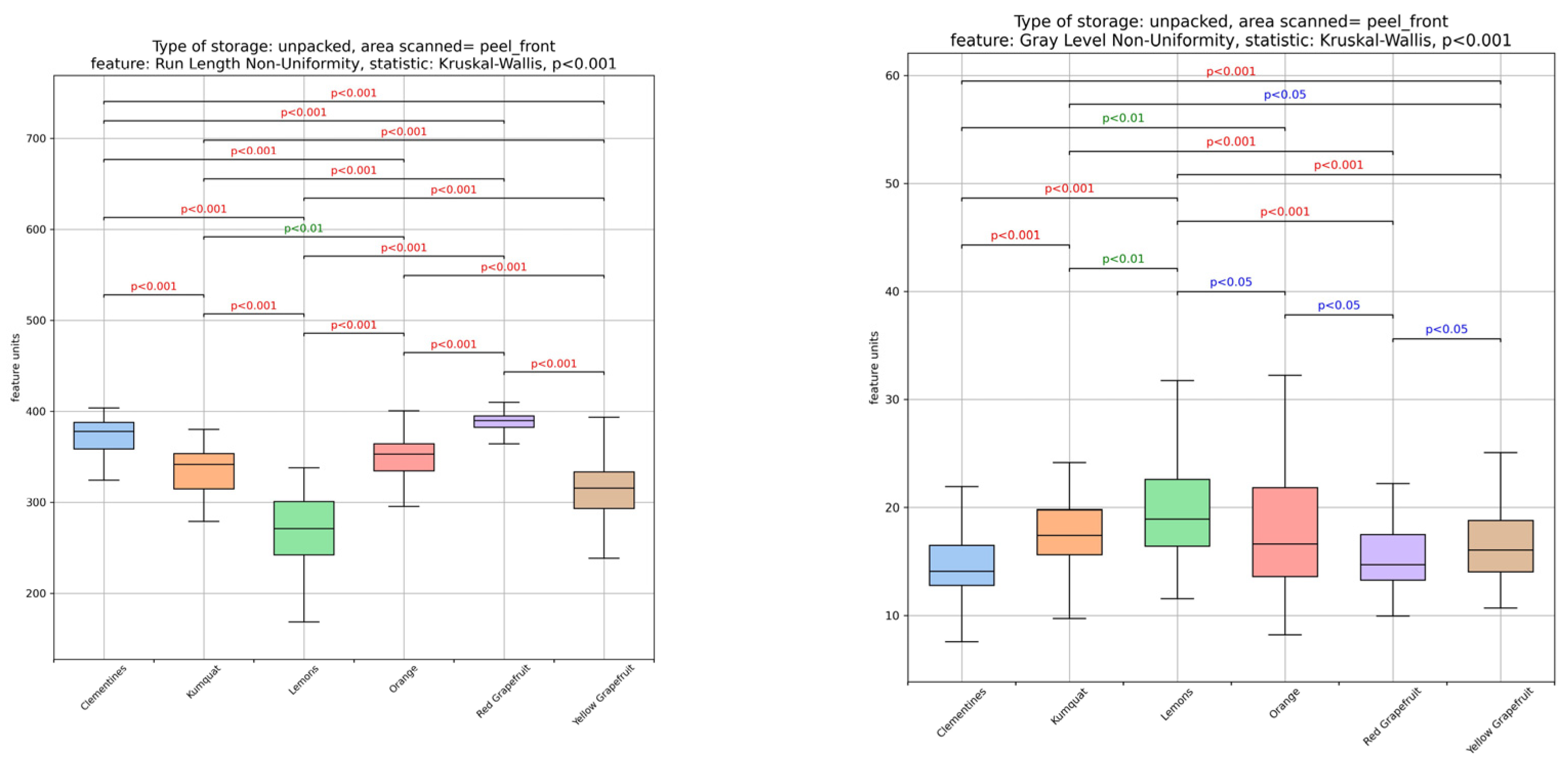

2.2. Image Analysis of the Surface of Citrus Peels

2.3. Physicochemical Measurements

2.4. Extraction of Phenolic Compounds and Spectrophotometric Assays

2.5. Attenuated Total Reflectance–Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR)

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.7. Chemometric Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Textural Image Analysis of Citrus Fruit Peels

3.2. Physicochemical Parameters of Citrus Fruit Peels

3.3. Spectrophotometric Assays of Citrus Fruit Peels

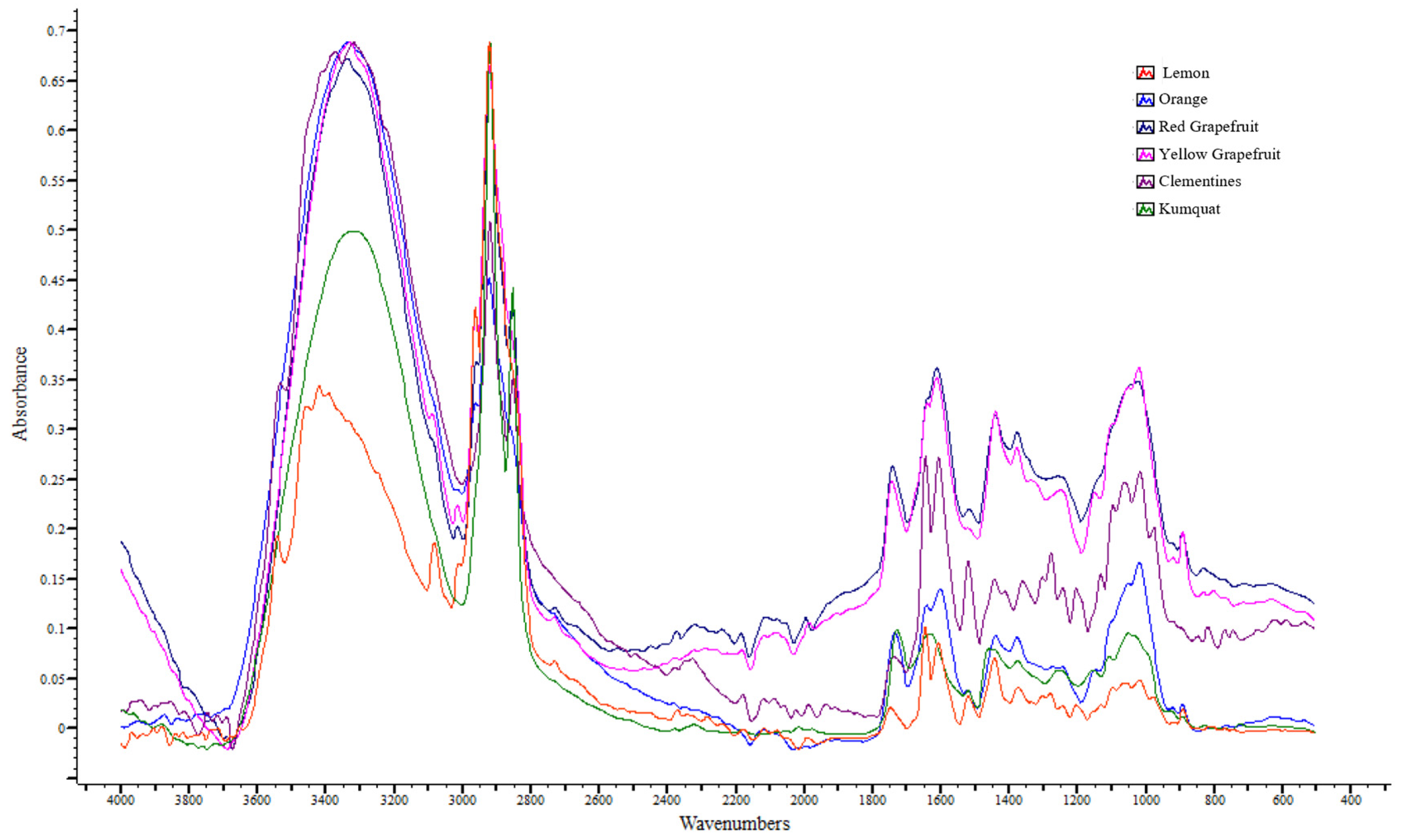

3.4. Interpretation of Attenuated Total Reflection–Fourier Transform Infrared (ATR-FTIR) Spectra

3.5. Chemometric Analysis of the Analytical Methods

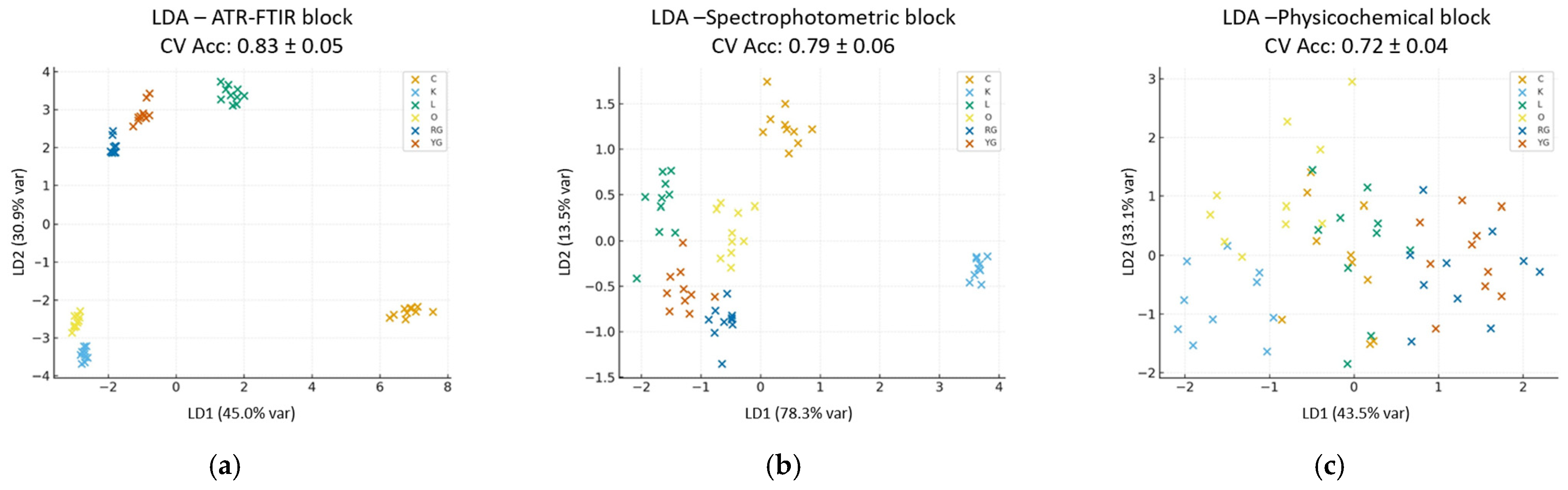

3.5.1. Single-Block Model

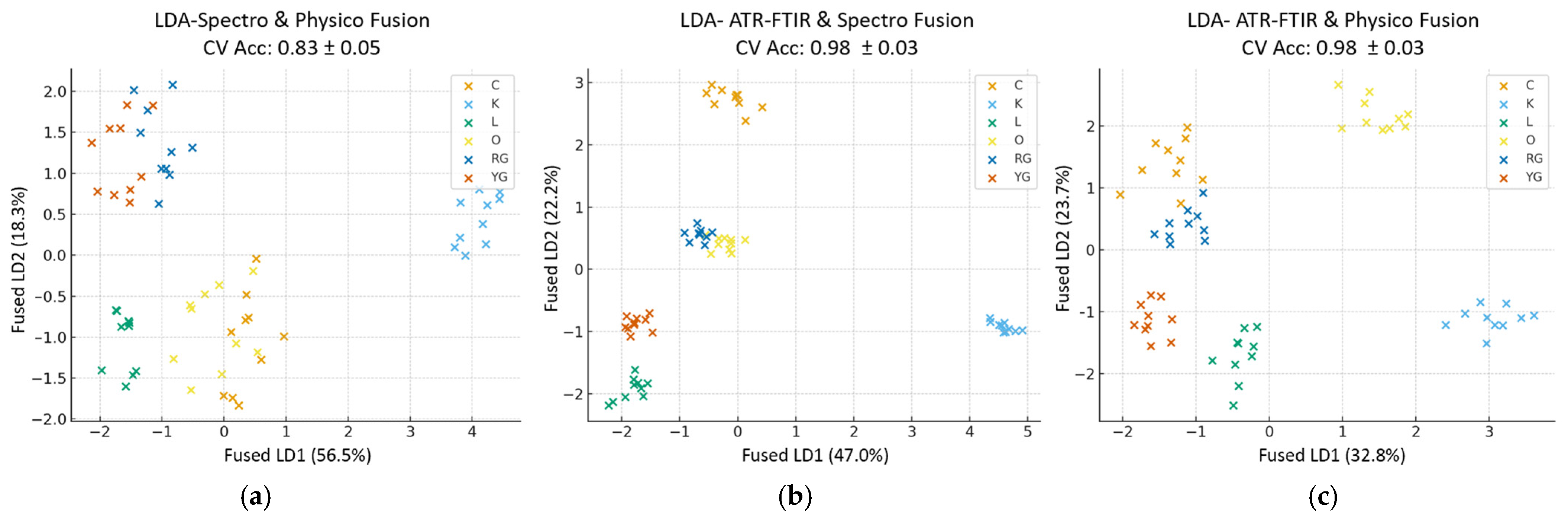

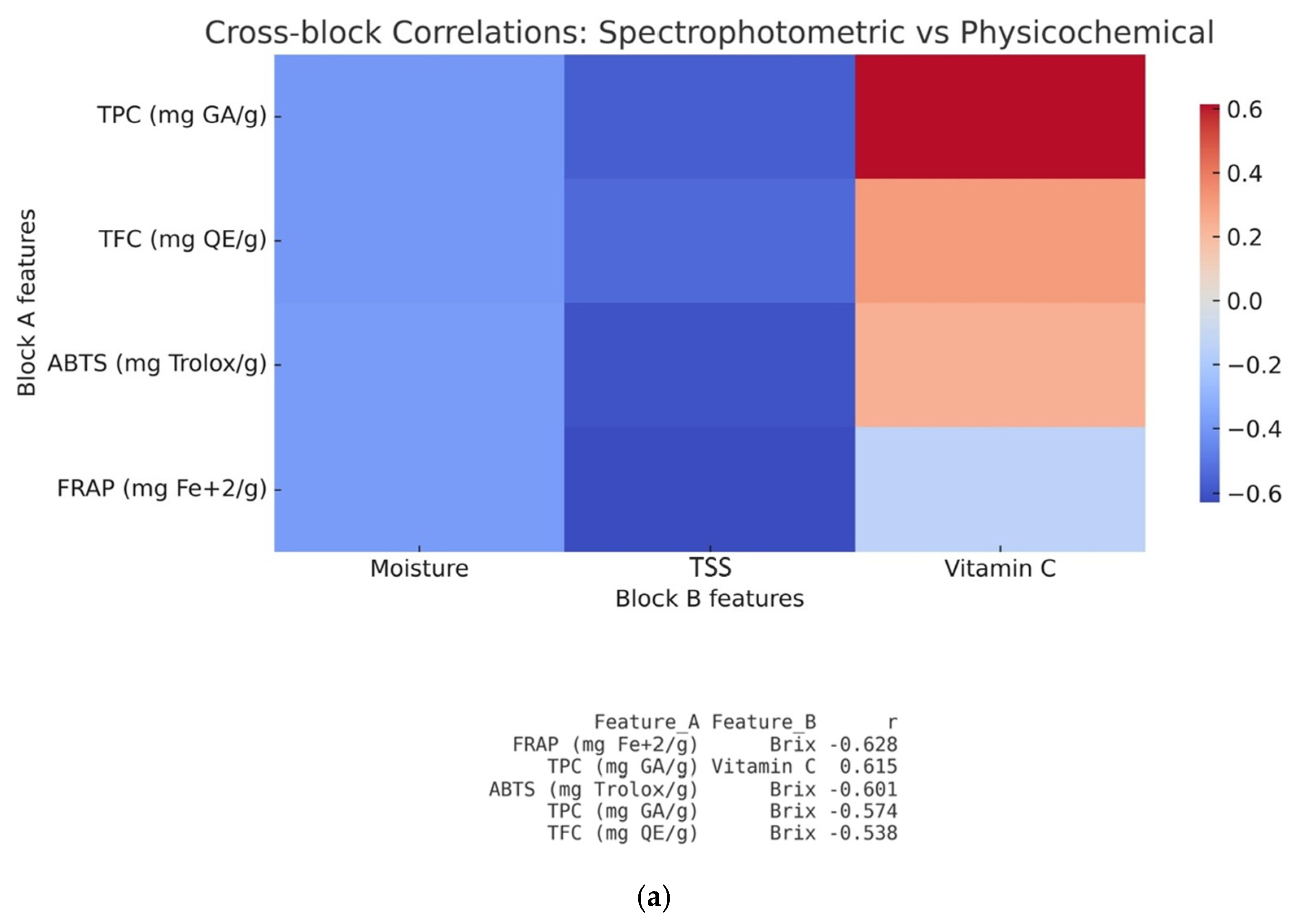

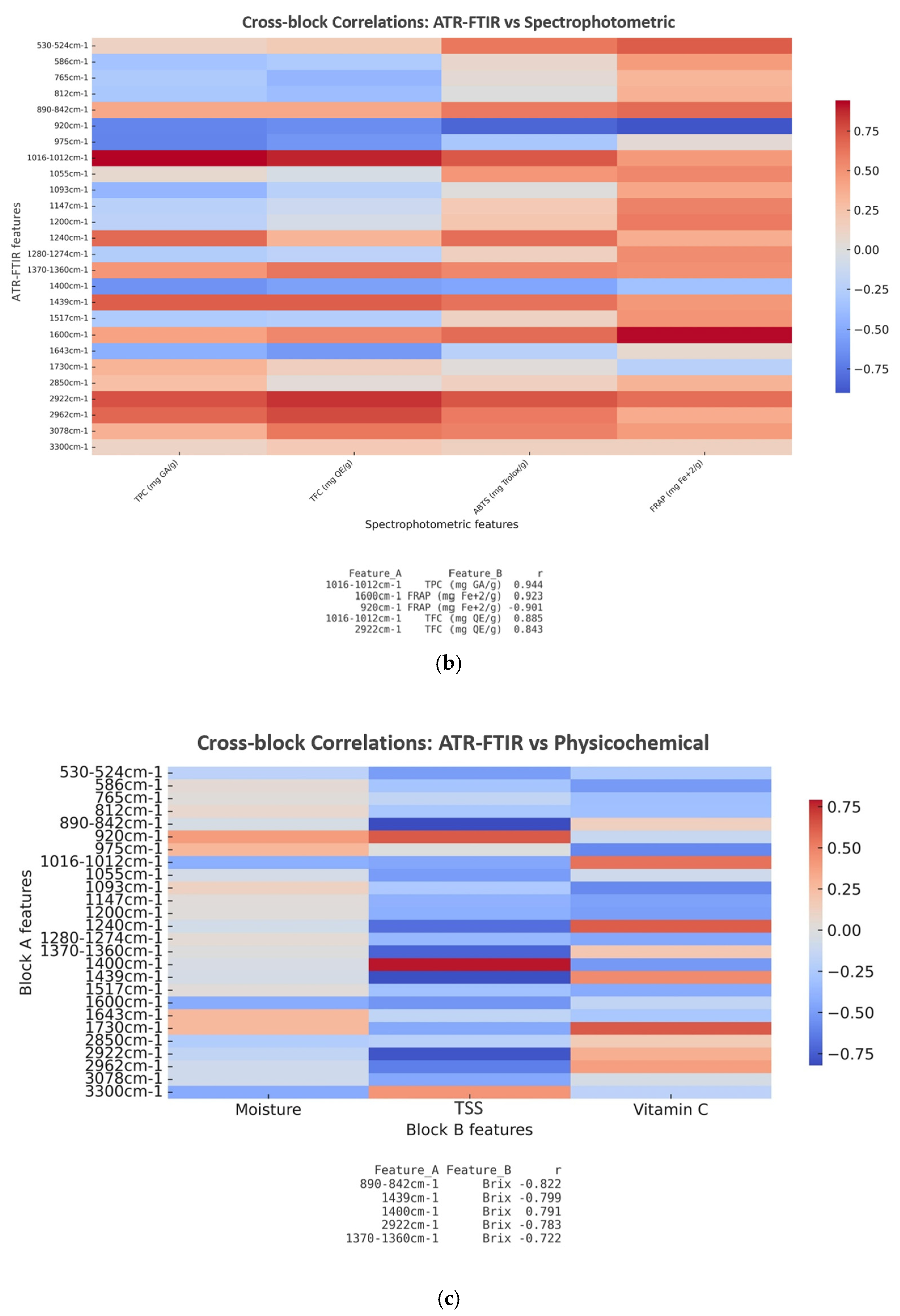

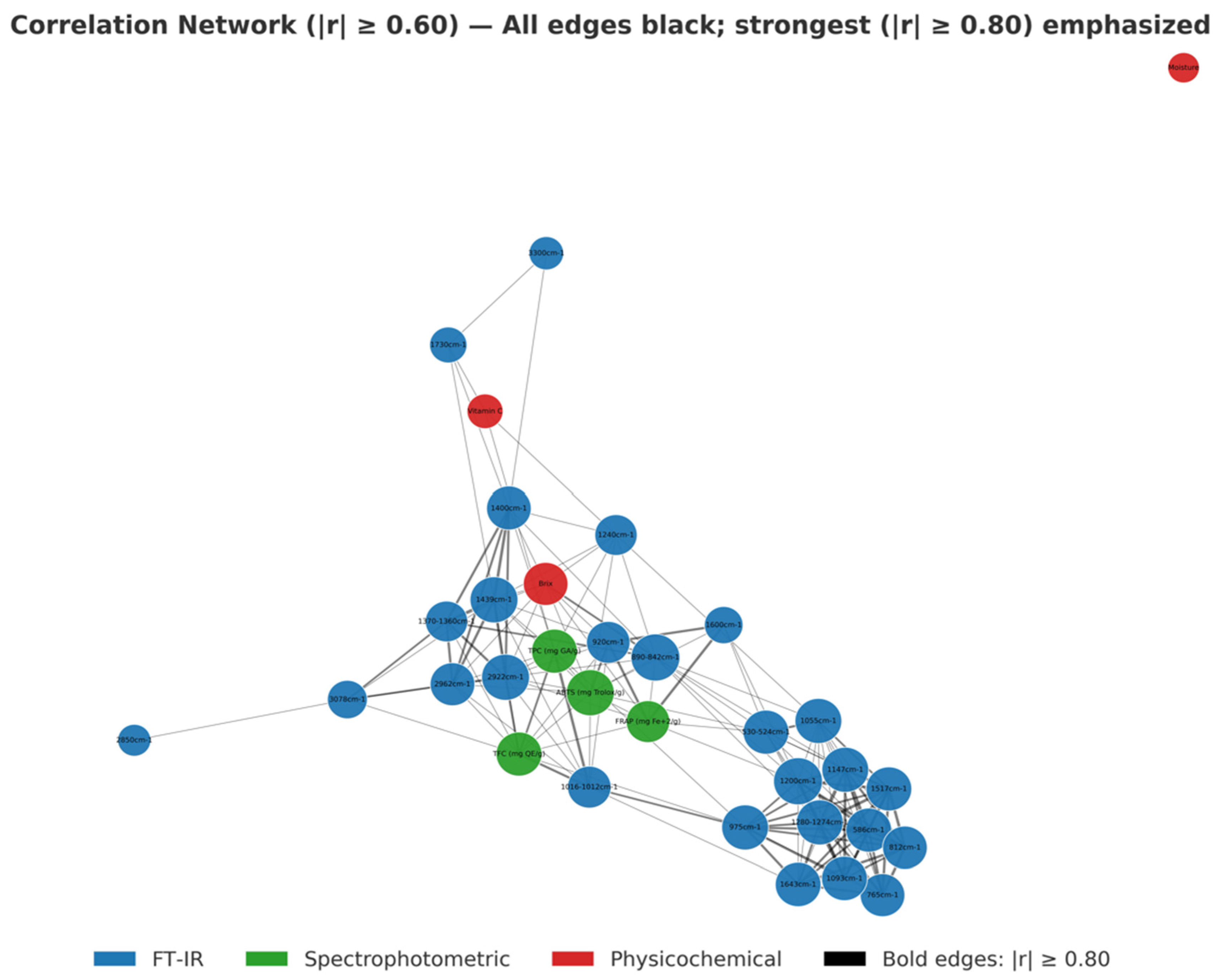

3.5.2. Cross-Block Fusion

3.5.3. Multi-Block Fusion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lv, X.; Zhao, S.; Ning, Z.; Zeng, H.; Shu, Y.; Tao, O.; Xiao, C.; Lu, C.; Liu, Y. Citrus Fruits as a Treasure Trove of Active Natural Metabolites That Potentially Provide Benefits for Human Health. Chem. Cent. J. 2015, 9, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.A.; Terol, J.; Ibanez, V.; López-García, A.; Pérez-Román, E.; Borredá, C.; Domingo, C.; Tadeo, F.R.; Carbonell-Caballero, J.; Alonso, R.; et al. Genomics of the Origin and Evolution of Citrus. Nature 2018, 554, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denaro, M.; Smeriglio, A.; Xiao, J.; Cornara, L.; Burlando, B.; Trombetta, D. New Insights into Citrus Genus: From Ancient Fruits to New Hybrids. Food Front. 2020, 1, 305–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.B.; Karagiannis, E.; Manzoor, M.; Ziogas, V. From Stress to Success: Harnessing Technological Advancements to Overcome Climate Change Impacts in Citriculture. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2023, 42, 345–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO) Production of Crops and Livestock Products. 2024. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Putnik, P.; Barba, F.J.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Gabrić, D.; Shpigelman, A.; Cravotto, G.; Bursać Kovačević, D. An Integrated Approach to Mandarin Processing: Food Safety and Nutritional Quality, Consumer Preference, and Nutrient Bioaccessibility. Comp. Rev. Food Sci. Food Safe 2017, 16, 1345–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Zhao, C.; Shi, H.; Liao, Y.; Xu, F.; Du, H.; Xiao, H.; Zheng, J. Nutrients and Bioactives in Citrus Fruits: Different Citrus Varieties, Fruit Parts, and Growth Stages. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 2018–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, P.; Tripathi, G.; Mir, S.S.; Yousuf, O. Current Scenario and Global Perspectives of Citrus Fruit Waste as a Valuable Resource for the Development of Food Packaging Film. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 141, 104190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Li, X.; Zhao, P.; Zhang, X.; Qiao, O.; Huang, L.; Guo, L.; Gao, W. A Review of Chemical Constituents and Health-Promoting Effects of Citrus Peels. Food Chem. 2021, 365, 130585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahmi, F.; Mokhtari, O.; Legssyer, B.; Hamdani, I.; Asehraou, A.; Hasnaoui, I.; Rokni, Y.; Diass, K.; Oualdi, I.; Tahani, A. Chemical and Biological Characterization of Essential Oils Extracted from Citrus Fruits Peels. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 45, 7794–7799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, D.; Park, H.; Jang, B.-K.; Ju, Y.; Shin, M.H.; Oh, E.J.; Lee, E.J.; Kim, S.R. Recent Advances in the Biological Valorization of Citrus Peel Waste into Fuels and Chemicals. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 323, 124603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Singh, J.P.; Kaur, A.; Yadav, M.P. Insights into the Chemical Composition and Bioactivities of Citrus Peel Essential Oils. Food Res. Int. 2021, 143, 110231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwar, D.; Saini, A.; Panesar, P.S.; Chopra, H.K. Unraveling the Scientific Perspectives of Citrus By-Products Utilization: Progress towards Circular Economy. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 111, 549–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.S.; Silva, A.M.; Nunes, F.M. Citrus reticulata Blanco Peels as a Source of Antioxidant and Anti-Proliferative Phenolic Compounds. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 111, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, H.R.D.M.; Ferreira, T.A.P.D.C.; Genovese, M.I. Antioxidant Capacity and Mineral Content of Pulp and Peel from Commercial Cultivars of Citrus from Brazil. Food Chem. 2012, 134, 1892–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sir Elkhatim, K.A.; Elagib, R.A.A.; Hassan, A.B. Content of Phenolic Compounds and Vitamin C and Antioxidant Activity in Wasted Parts of Sudanese Citrus Fruits. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 6, 1214–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azman, N.F.I.N.; Azlan, A.; Khoo, H.E.; Razman, M.R. Antioxidant Properties of Fresh and Frozen Peels of Citrus Species. Curr. Res. Nutr. Food Sci. 2019, 7, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Hu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Z. The Maturity Degree, Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of Eureka Lemon [Citrus limon (L.) Burm. f.]: A Negative Correlation between Total Phenolic Content, Antioxidant Capacity and Soluble Solid Content. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 243, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, C.S.E.; Anunciação, P.C.; Lucia, C.M.D.; Dôres, R.G.R.D.; Milagres, R.C.R.D.M.; Sant’Ana, H.M.P. Kumquat (Fortunella margarita): A Good Alternative for the Ingestion of Nutrients and Bioactive Compounds. In Proceedings of the 1st International Electronic Conference on Food Science and Functional Foods, Online, 10–25 November 2020; p. 105. [Google Scholar]

- Czech, A.; Zarycka, E.; Yanovych, D.; Zasadna, Z.; Grzegorczyk, I.; Kłys, S. Mineral Content of the Pulp and Peel of Various Citrus Fruit Cultivars. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2020, 193, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tayyab, M.; Hanif, M.; Rafey, A.; Amanullah; Mohibullah, M.; Rasool, S.; Mahmood, F.U.; Khan, N.R.; Aziz, N.; Amin, A. UHPLC, ATR-FTIR Profiling and Determination of 15 LOX, α-Glucosidase, Ages Inhibition and Antibacterial Properties of Citrus Peel Extracts. Pharm. Chem. J. 2021, 55, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carullo, G.; Ramunno, A.; Sommella, E.M.; De Luca, M.; Belsito, E.L.; Frattaruolo, L.; Brindisi, M.; Campiglia, P.; Cappello, A.R.; Aiello, F. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction, Chemical Characterization, and Impact on Cell Viability of Food Wastes Derived from Southern Italy Autochthonous Citrus Fruits. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toprakçı, İ.; Balci-Torun, F.; Deniz, N.G.; Ortaboy, S.; Torun, M.; Şahin, S. Recovery of Citrus Volatile Substances from Orange Juice Waste: Characterization with GC-MS, FTIR, 1H- and 13C-NMR Spectroscopies. Phytochem. Lett. 2023, 57, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, H.; Iahtisham-Ul-Haq; Butt, M.S.; Nayik, G.A.; Ramniwas, S.; Damto, T.; Ali Alharbi, S.; Ansari, M.J. Phytochemical and Antioxidant Profile of Citrus Peel Extracts in Relation to Different Extraction Parameters. Int. J. Food Prop. 2024, 27, 286–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, J.J.; Tavares, H.M.; Curbelo, R.; Dellacassa, E.; Cassel, E.; Apel, M.A.; Von Poser, G.L.; Vargas, R.M.F. Supercritical Fluid Extraction of Coumarins and Flavonoids from Citrus Peel. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2025, 215, 106396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Gregorio, M.R.; Regueiro, J.; González-Barreiro, C.; Rial-Otero, R.; Simal-Gándara, J. Changes in Antioxidant Flavonoids during Freeze-Drying of Red Onions and Subsequent Storage. Food Control 2011, 22, 1108–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Hernndez, M.; Palma-Tenango, M.; Garcia-Mateos, M.D.R. (Eds.) Phenolic Compounds—Biological Activity; InTech: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-953-51-2959-2. [Google Scholar]

- Christodoulou, P.; Kritsi, E.; Ladika, G.; Tsafou, P.; Tsiantas, K.; Tsiaka, T.; Zoumpoulakis, P.; Cavouras, D.; Sinanoglou, V.J. Estimation of Tomato Quality During Storage by Means of Image Analysis, Instrumental Analytical Methods, and Statistical Approaches. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, K.; Zhou, X.; Li, X.; Kang, Y.; Yang, X.; Cui, Y.; Li, G.; Pei, X.; Zhao, X. Insight into the Multiple Branches Traits of a Mutant in Larix olgensis by Morphological, Cytological, and Transcriptional Analyses. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 787661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pegg, R.B.; Eitenmiller, R.R. Vitamin Analysis. In Food Analysis; Nielsen, S.S., Ed.; Food Science Text Series; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 361–370. ISBN 978-3-319-45774-1. [Google Scholar]

- Andreou, V.; Strati, I.F.; Fotakis, C.; Liouni, M.; Zoumpoulakis, P.; Sinanoglou, V.J. Herbal Distillates: A New Era of Grape Marc Distillates with Enriched Antioxidant Profile. Food Chem. 2018, 253, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matić, P.; Sabljić, M.; Jakobek, L. Validation of Spectrophotometric Methods for the Determination of Total Polyphenol and Total Flavonoid Content. J. AOAC Int. 2017, 100, 1795–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantzouraki, D.Z.; Sinanoglou, V.J.; Zoumpoulakis, P.; Proestos, C. Comparison of the Antioxidant and Antiradical Activity of Pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) by Ultrasound-Assisted and Classical Extraction. Anal. Lett. 2016, 49, 969–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantzouraki, D.Z.; Sinanoglou, V.J.; Zoumpoulakis, P.G.; Glamočlija, J.; Ćirić, A.; Soković, M.; Heropoulos, G.; Proestos, C. Antiradical–Antimicrobial Activity and Phenolic Profile of Pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) Juices from Different Cultivars: A Comparative Study. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 2602–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, A.G.; Kritsi, E.; Sinanoglou, V.J.; Cavouras, D.; Tsiaka, T.; Houhoula, D.; Zoumpoulakis, P.; Strati, I.F. Highlighting the Potential of Attenuated Total Reflectance—Fourier Transform Infrared (ATR-FTIR) Spectroscopy to Characterize Honey Samples with Principal Component Analysis (PCA). Anal. Lett. 2023, 56, 789–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinanoglou, V.J.; Tsiaka, T.; Aouant, K.; Mouka, E.; Ladika, G.; Kritsi, E.; Konteles, S.J.; Ioannou, A.-G.; Zoumpoulakis, P.; Strati, I.F.; et al. Quality Assessment of Banana Ripening Stages by Combining Analytical Methods and Image Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, S.; Sharma, K.; Kumar, K.; Thakur, A. Types and Cultivation of Citrus Fruits. In Citrus Fruits and Juice; Gupta, A.K., Kour, J., Mishra, P., Eds.; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2024; pp. 17–43. ISBN 978-981-99-8698-9. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, G.R.; Aldous, D.E. (Eds.) Horticulture: Plants for People and Places, Volume 1: Production Horticulture; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherland, 2014; ISBN 978-94-017-8577-8. [Google Scholar]

- Rey, F.; Zacarías, L.; Rodrigo, M.J. Carotenoids, Vitamin C, and Antioxidant Capacity in the Peel of Mandarin Fruit in Relation to the Susceptibility to Chilling Injury during Postharvest Cold Storage. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quevedo, R.; Mendoza, F.; Aguilera, J.M.; Chanona, J.; Gutiérrez-López, G. Determination of Senescent Spotting in Banana (Musa cavendish) Using Fractal Texture Fourier Image. J. Food Eng. 2008, 84, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Burks, T.F.; Kim, D.G.; Bulanon, D.M. Classification of Citrus Peel Diseases Using Color Texture Feature Analysis. In Proceedings of the Food Processing Automation Conference Proceedings, Providence, RI, USA, 28–29 June 2008; American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers: St Joseph, MI, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- López-García, F.; Andreu-García, G.; Blasco, J.; Aleixos, N.; Valiente, J.-M. Automatic Detection of Skin Defects in Citrus Fruits Using a Multivariate Image Analysis Approach. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2010, 71, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuño-Maganda, M.A.; Dávila-Rodríguez, I.A.; Hernández-Mier, Y.; Barrón-Zambrano, J.H.; Elizondo-Leal, J.C.; Díaz-Manriquez, A.; Polanco-Martagón, S. Real-Time Embedded Vision System for Online Monitoring and Sorting of Citrus Fruits. Electronics 2023, 12, 3891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadri, S.; Furqan Qadri, S.; Husnain, M.; Saad Missen, M.M.; Khan, D.M.; Muzammil-Ul-Rehman; Razzaq, A.; Ullah, S. Machine Vision Approach for Classification of Citrus Leaves Using Fused Features. Int. J. Food Prop. 2019, 22, 2072–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manninen, H.; Paakki, M.; Hopia, A.; Franzén, R. Measuring the Green Color of Vegetables from Digital Images Using Image Analysis. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 63, 1184–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladika, G.; Strati, I.F.; Tsiaka, T.; Cavouras, D.; Sinanoglou, V.J. On the Assessment of Strawberries’ Shelf-Life and Quality, Based on Image Analysis, Physicochemical Methods, and Chemometrics. Foods 2024, 13, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, P.; Ladika, G.; Tsiantas, K.; Kritsi, E.; Tsiaka, T.; Cavouras, D.; Zoumpoulakis, P.; Sinanoglou, V.J. Quality Assessment of Greenhouse-Cultivated Cucumbers (Cucumis sativus) during Storage Using Instrumental and Image Analyses. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Mejía, E.; Sacristán, I.; Rosales-Conrado, N.; León-González, M.E.; Madrid, Y. Effect of Storage and Drying Treatments on Antioxidant Activity and Phenolic Composition of Lemon and Clementine Peel Extracts. Molecules 2023, 28, 1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, P.D.; Mandavgane, S.A.; Kulkarni, B.D. Fruit Peel Waste: Characterization and Its Potential Uses. Curr. Sci. 2017, 113, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.; Nguyen, N.T.P.; Dinh, D.V.; Kieu, N.T.; Bach, L.G.; Phong, H.X.; Muoi, N.V.; Truc, T.T. Evaluate the Chemical Composition of Peels and Juice of Seedless Lemon (Citrus latifolia) Grown in Hau Giang Province, Vietnam. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 991, 012127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, C.; Maugeri, A.; Lombardo, G.E.; Musumeci, L.; Barreca, D.; Rapisarda, A.; Cirmi, S.; Navarra, M. The Second Life of Citrus Fruit Waste: A Valuable Source of Bioactive Compounds. Molecules 2021, 26, 5991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammoun Bejar, A.; Ghanem, N.; Mihoubi, D.; Kechaou, N.; Boudhrioua Mihoubi, N. Effect of Infrared Drying on Drying Kinetics, Color, Total Phenols and Water and Oil Holding Capacities of Orange (Citrus sinensis) Peel and Leaves. Int. J. Food Eng. 2011, 7, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M’hiri, N.; Ioannou, I.; Ghoul, M.; Mihoubi Boudhrioua, N. Phytochemical Characteristics of Citrus Peel and Effect of Conventional and Nonconventional Processing on Phenolic Compounds: A Review. Food Rev. Int. 2017, 33, 587–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marey, S.; Shoughy, M. Effect of Temperature on the Drying Behavior and Quality of Citrus Peels. Int. J. Food Eng. 2016, 12, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatin Najwa, R.; Azrina, A. Comparison of Vitamin C Content in Citrus Fruits by Titration and High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) Methods. Int. Food Res. J. 2017, 24, 726–733. [Google Scholar]

- Alós, E.; Rodrigo, M.J.; Zacarías, L. Differential Transcriptional Regulation of L-Ascorbic Acid Content in Peel and Pulp of Citrus Fruits during Development and Maturation. Planta 2014, 239, 1113–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawełczyk, A.; Żwawiak, J.; Zaprutko, L. Kumquat Fruits as an Important Source of Food Ingredients and Utility Compounds. Food Rev. Int. 2023, 39, 875–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Rattanpal, H.S.; Gul, K.; Dar, R.A.; Sharma, A. Chemical Composition, Antioxidant Activity and GC-MS Analysis of Juice and Peel Oil of Grapefruit Varieties Cultivated in India. J. Integr. Agric. 2019, 18, 1634–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam-Eldein, S.; Albrigo, G.; Rouseff, R.; Tubeileh, A. Characterization of Citrus Peel Maturation: Multivariate and Multiple Regression Analyses. Acta Hortic. 2017, 1160, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Li, S.; Du, G.; Jiang, L.; Liu, X.; Ding, S.; Shan, Y. A Simple and Nondestructive Approach for the Analysis of Soluble Solid Content in Citrus by Using Portable Visible to Near-infrared Spectroscopy. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 2543–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, M.M.; Roy, P.; Alam, M.; Hoque, M.M.; Zzaman, W. Antimicrobial Activity of Peels and Physicochemical Properties of Juice Prepared from Indigenous Citrus Fruits of Sylhet Region, Bangladesh. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Saif, A.M.; Abdel-Sattar, M.; Eshra, D.H.; Sas-Paszt, L.; Mattar, M.A. Predicting the Chemical Attributes of Fresh Citrus Fruits Using Artificial Neural Network and Linear Regression Models. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas-Cantu, R.C.; Jones, K.D.; Mills, P.L. A Citrus Waste-Based Biorefinery as a Source of Renewable Energy: Technical Advances and Analysis of Engineering Challenges. Waste Manag. Res. 2013, 31, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.B.; Smith, B.; Hossain, M.M. Extraction of Phenolics from Citrus Peels. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2006, 48, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, T.; Khan, M.R.; Shabbir, M.A.; Zia, M.A. Phytochemical Profiling and HPLC Quantification of Citrus Peel from Different Varieties. Prog. Nutr. 2018, 20, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata, R.; Martínez-Zamora, L.; Artés-Hernández, F. Diversity of Color, Infrared Spectra, and Phenolic Profile Correlation in Citrus Fruit Peels. In Proceedings of the 5th International Electronic Conference on Foods, Online, 28–30 October 2024; p. 26. [Google Scholar]

- Ramful, D.; Bahorun, T.; Bourdon, E.; Tarnus, E.; Aruoma, O.I. Bioactive Phenolics and Antioxidant Propensity of Flavedo Extracts of Mauritian Citrus Fruits: Potential Prophylactic Ingredients for Functional Foods Application. Toxicology 2010, 278, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diab, K.A. In Vitro Studies on Phytochemical Content, Antioxidant, Anticancer, Immunomodulatory, and Antigenotoxic Activities of Lemon, Grapefruit, and Mandarin Citrus Peels. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2016, 17, 3559–3567. [Google Scholar]

- Goulas, V.; Manganaris, G.A. Exploring the Phytochemical Content and the Antioxidant Potential of Citrus Fruits Grown in Cyprus. Food Chem. 2012, 131, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiq, S.; Kaul, R.; Sofi, S.A.; Bashir, N.; Nazir, F.; Ahmad Nayik, G. Citrus Peel as a Source of Functional Ingredient: A Review. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2018, 17, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addi, M.; Elbouzidi, A.; Abid, M.; Tungmunnithum, D.; Elamrani, A.; Hano, C. An Overview of Bioactive Flavonoids from Citrus Fruits. Appl. Sci. 2021, 12, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mare, R.; Pujia, R.; Maurotti, S.; Greco, S.; Cardamone, A.; Coppoletta, A.R.; Bonacci, S.; Procopio, A.; Pujia, A. Assessment of Mediterranean Citrus Peel Flavonoids and Their Antioxidant Capacity Using an Innovative UV-Vis Spectrophotometric Approach. Plants 2023, 12, 4046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Immanuel, G. Extraction of Antioxidants from Fruit Peels and Its Utilization in Paneer. J. Food Process Technol. 2014, 5, 1000349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Wang, D.; Tan, C.; Hu, Y.; Sundararajan, B.; Zhou, Z. Profiling of Flavonoid and Antioxidant Activity of Fruit Tissues from 27 Chinese Local Citrus Cultivars. Plants 2020, 9, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-C.; Chuang, Y.-C.; Ku, Y.-H. Quantitation of Bioactive Compounds in Citrus Fruits Cultivated in Taiwan. Food Chem. 2007, 102, 1163–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukhtenko, H.; Bevz, N.; Konechnyi, Y.; Kukhtenko, O.; Jasicka-Misiak, I. Spectrophotometric and Chromatographic Assessment of Total Polyphenol and Flavonoid Content in Rhododendron Tomentosum Extracts and Their Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activity. Molecules 2024, 29, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saini, R.K.; Ranjit, A.; Sharma, K.; Prasad, P.; Shang, X.; Gowda, K.G.M.; Keum, Y.-S. Bioactive Compounds of Citrus Fruits: A Review of Composition and Health Benefits of Carotenoids, Flavonoids, Limonoids, and Terpenes. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bratovcic, A.; Djapo-Lavic, M.; Kazazic, M.; Mehic, E. Evaluation of Antioxidant Capacities of Orange, Lemon, Apple and Banana Peel Extracts by Frap and Abts Methods. Rev. Roum. Chim. 2021, 66, 713–717. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Hsouna, A.; Sadaka, C.; Generalić Mekinić, I.; Garzoli, S.; Švarc-Gajić, J.; Rodrigues, F.; Morais, S.; Moreira, M.M.; Ferreira, E.; Spigno, G.; et al. The Chemical Variability, Nutraceutical Value, and Food-Industry and Cosmetic Applications of Citrus Plants: A Critical Review. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanmani, P.; Dhivya, E.; Aravind, J.; Kumaresan, K. Extraction and Analysis of Pectin from Citrus Peels: Augmenting the Yield from Citrus limon Using Statistical Experimental Design. Iran. J. Energy Environ. 2014, 5, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandiyanto, A.B.D.; Oktiani, R.; Ragadhita, R. How to Read and Interpret FTIR Spectroscope of Organic Material. Indones. J. Sci. Technol. 2019, 4, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, R.S.; Al-Dbass, A.M.; Khayyat, A.I.A.; Al-Daihan, S. Utilizing Biomolecule-Rich Citrus Fruit Waste as a Medium for the Eco-Friendly Preparation of Silver Nanoparticles with Antimicrobial Properties. Inorganics 2024, 12, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Castro, S.C.; Stanisic, D.; Tasic, L. Sequential Extraction of Hesperidin, Pectin, Lignin, and Cellulose from Orange Peels: Towards Valorization of Agro-waste. Biofuels Bioprod. Bioref 2024, 18, 804–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciccoritti, R.; Ciorba, R.; Ceccarelli, D.; Amoriello, M.; Amoriello, T. Phytochemical and Functional Properties of Fruit and Vegetable Processing By-Products. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozłowicz, K.; Różyło, R.; Gładyszewska, B.; Matwijczuk, A.; Gładyszewski, G.; Chocyk, D.; Samborska, K.; Piekut, J.; Smolewska, M. Identification of Sugars and Phenolic Compounds in Honey Powders with the Use of GC–MS, FTIR Spectroscopy, and X-Ray Diffraction. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 16269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deo, S.K.; Sakhale, B.K. Phytochemical Analysis of Citrus limetta Using High-Resolution Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometry (HR-LCMS) and FTIR. Sust. Agric. Food Env. Res. 2023, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Z.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, Z.; Xu, X.; Chen, B.; Yang, D.; Zheng, G. Characterization of Antioxidant Compounds Extracted from Citrus reticulata Cv. Chachiensis Using UPLC-Q-TOF-MS/MS, FT-IR and Scanning Electron Microscope. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2021, 192, 113683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küçük, İ. Characterization of Citrus paradisi Peel Powder and Investigation of Lead(II) Biosorption. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 22, 3163–3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hădărugă, N.G.; Popescu, G.; Gligor (Pane), D.; Mitroi, C.L.; Stanciu, S.M.; Hădărugă, D.I. Discrimination of β-Cyclodextrin/Hazelnut (Corylus avellana L.) Oil/Flavonoid Glycoside and Flavonolignan Ternary Complexes by Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy Coupled with Principal Component Analysis. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2023, 19, 380–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minutti-López Sierra, P.; Gallardo-Velázquez, T.; Osorio-Revilla, G.; Meza-Márquez, O.G. Chemical Composition and Antioxidant Capacity in Strawberry Cultivars (Fragaria x Ananassa Duch.) by FT-MIR Spectroscopy and Chemometrics. CyTA-J. Food 2019, 17, 724–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skolik, P.; Morais, C.L.M.; Martin, F.L.; McAinsh, M.R. Determination of Developmental and Ripening Stages of Whole Tomato Fruit Using Portable Infrared Spectroscopy and Chemometrics. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krysa, M.; Szymańska-Chargot, M.; Zdunek, A. FT-IR and FT-Raman Fingerprints of Flavonoids—A Review. Food Chem. 2022, 393, 133430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movasaghi, Z.; Rehman, S.; Ur Rehman, D.I. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy of Biological Tissues. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2008, 43, 134–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Feng, X.; Ma, Y. Activated Carbon from Chili Straw: K2CO3 Activation Mechanism, Adsorption of Dyes, and Thermal Regeneration. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2024, 14, 19563–19580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canteri, M.H.G.; Renard, C.M.G.C.; Le Bourvellec, C.; Bureau, S. ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy to Determine Cell Wall Composition: Application on a Large Diversity of Fruits and Vegetables. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 212, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talari, A.C.S.; Martinez, M.A.G.; Movasaghi, Z.; Rehman, S.; Rehman, I.U. Advances in Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy of Biological Tissues. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2017, 52, 456–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassani, L.; Santos, M.; Gerbino, E.; Del Rosario Moreira, M.; Gómez-Zavaglia, A. A Combined Approach of Infrared Spectroscopy and Multivariate Analysis for the Simultaneous Determination of Sugars and Fructans in Strawberry Juices During Storage. J. Food Sci. 2018, 83, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamil, M.M.; Mohamed, G.F.; Shaheen, M.S. Fourier Transformer Infrared Spectroscopy for Quality Assurance of Tomato Products. J. Am. Sci. 2011, 7, 559–572. [Google Scholar]

- Tsirigotis-Maniecka, M.; Gancarz, R.; Wilk, K.A. Polysaccharide Hydrogel Particles for Enhanced Delivery of Hesperidin: Fabrication, Characterization and in Vitro Evaluation. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2017, 532, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buljeta, I.; Pichler, A.; Šimunović, J.; Kopjar, M. Polyphenols and Antioxidant Activity of Citrus Fiber/Blackberry Juice Complexes. Molecules 2021, 26, 4400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-C.; Chuang, Y.-C.; Hsu, H.-W. The Flavonoid, Carotenoid and Pectin Content in Peels of Citrus Cultivated in Taiwan. Food Chem. 2008, 106, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Labrador, A.; Moreno, R.; Villamiel, M.; Montilla, A. Preparation of Citrus Pectin Gels by Power Ultrasound and Its Application as an Edible Coating in Strawberries. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 4866–4875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentahar, A.; Bouaziz, A.; Djidel, S.; Khennouf, S. Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Activity of Ethanolic Extracts from Citrus sinensis L. and Citrus reticulata L. Fruits. J. Drug Deliv. Ther. 2020, 10, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Yang, W.; Li, X.; Zhao, P.; Liu, Y.; Guo, L.; Huang, L.; Gao, W. Comparison of Characterization and Antioxidant Activity of Different Citrus Peel Pectins. Food Chem. 2022, 386, 132683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, M.; Verma, S.; Pandey, S. Comparative Analysis of Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Properties of Citrus Peels and Its Importance: A Review. Pharma Innov. 2024, 13, 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Xi, W.; Zhang, G.; Jiang, D.; Zhou, Z. Phenolic Compositions and Antioxidant Activities of Grapefruit (Citrus paradisi Macfadyen) Varieties Cultivated in China. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015, 66, 858–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, J.; Liang, L.; Su, M.; Yang, T.; Mao, X.; Wang, Y. Variations in Phenolic Acids and Antioxidant Activity of Navel Orange at Different Growth Stages. Food Chem. 2021, 360, 129980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Mahato, N.; Lee, Y.R. Extraction, Characterization and Biological Activity of Citrus Flavonoids. Rev. Chem. Eng. 2019, 35, 265–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Meenu, M.; Xu, B. Recent Development in Bioactive Compounds and Health Benefits of Kumquat Fruits. Food Rev. Int. 2023, 39, 4312–4332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suri, S.; Singh, A.; Nema, P.K. Current Applications of Citrus Fruit Processing Waste: A Scientific Outlook. Appl. Food Res. 2022, 2, 100050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Le Bourvellec, C.; Renard, C.M.G.C. Interactions between Cell Wall Polysaccharides and Polyphenols: Effect of Molecular Internal Structure. Comp. Rev. Food Sci. Food Safe 2020, 19, 3574–3617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, F. Interactions between Cell Wall Polysaccharides and Polyphenols. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 1808–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigano, M.M.; Lionetti, V.; Raiola, A.; Bellincampi, D.; Barone, A. Pectic Enzymes as Potential Enhancers of Ascorbic Acid Production through the D -Galacturonate Pathway in Solanaceae. Plant Sci. 2018, 266, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojtunik-Kulesza, K.A. Approach to Optimization of FRAP Methodology for Studies Based on Selected Monoterpenes. Molecules 2020, 25, 5267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falleh, H.; Ben Jemaa, M.; Saada, M.; Ksouri, R. Essential Oils: A Promising Eco-Friendly Food Preservative. Food Chem. 2020, 330, 127268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, M.A.; Barbosa, C.H.; Shah, M.A.; Ahmad, N.; Vilarinho, F.; Khwaldia, K.; Silva, A.S.; Ramos, F. Citrus By-Products: Valuable Source of Bioactive Compounds for Food Applications. Antioxidants 2022, 12, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Shannon, C.P.; Gautier, B.; Rohart, F.; Vacher, M.; Tebbutt, S.J.; Lê Cao, K.-A. DIABLO: An Integrative Approach for Identifying Key Molecular Drivers from Multi-Omics Assays. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 3055–3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konishi, T. Means and Issues for Adjusting Principal Component Analysis Results. Algorithms 2025, 18, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Du, C.; Wang, X.; Gao, F.; Lu, J.; Di, X.; Zhuang, X.; Cheng, C.; Yao, F. Multivariate Analysis between Environmental Factors and Fruit Quality of Citrus at the Core Navel Orange-Producing Area in China. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1510827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Negi, P.S. Multivariate Analysis of the Efficiency of Bio-Actives Extraction from Laboratory-Generated By-Products of Citrus reticulata Blanco. J. Food Sci. 2025, 90, e70304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandan, A.; Tripathi, A.D.; Khan, J.M.; Mahto, D.K.; Agarwal, A. Functional Profiling of Dried Citrus sinensis and Citrus limetta Peels: A Multivariate and Spectroscopic Insight into Waste Valorization. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2025, 48, 102251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Moisture Content (%) (Fresh Peel) | Ascorbic Acid (mg/100 g DW) | TSS (°Brix) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yellow Grapefruit (C. paradisi) | 67.76 ± 4.00 a | 114.12 ± 12.71 a | 10.73 ± 0.90 a |

| Red Grapefruit (C. paradisi) | 69.85 ± 4.21 ab | 104.54 ± 12.54 a | 10.30 ± 1.34 a |

| Lemon (C. limon) | 68.36 ± 5.66 ab | 56.78 ± 12.64 b | 10.00 ± 1.70 a |

| Orange (C. sinensis cv. Valencia) | 63.92 ± 5.61 a | 65.13 ± 12.69 b | 15.55 ± 1.44 b |

| Clementine (C. clementina) | 69.82 ± 5.62 ab | 56.89 ± 12.67 b | 10.80 ± 1.69 a |

| Kumquat (C. margarita) | 74.95 ± 3.53 b | 65.01 ± 5.07 b | 17.43 ± 2.38 b |

| Sample | TPC (mg GAE/g DW) | TFC (mg QE/g DW) | FRAP (mg Fe+2/g DW) | ABTS•+ (mg Trolox/g DW) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yellow Grapefruit (C. paradisi) | 18.21 ± 0.56 a | 27.01 ± 2.00 a | 31.82 ± 2.16 a | 19.92 ± 1.37 a |

| Red Grapefruit (C. paradisi) | 17.42 ± 0.83 a | 24.30 ± 1.83 a | 30.32 ± 1.45 a | 14.26 ± 0.65 b |

| Lemon (C. limon) | 14.29 ± 1.27 b | 31.90 ± 2.16 b | 42.10 ± 2.12 b | 18.66 ± 0.86 a |

| Orange (C. sinensis cv. Valencia) | 13.62 ± 1.05 b | 24.16 ± 2.13 a | 34.84 ± 3.44 ac | 16.13 ± 1.15 b |

| Clementine (C. clementina) | 9.90 ± 0.72 c | 13.91 ± 1.07 c | 39.50 ± 2.62 bc | 15.39 ± 1.12 b |

| Kumquat (C. margarita) | 4.86 ± 0.53 d | 7.63 ± 0.98 d | 13.16 ± 0.98 d | 6.71 ± 0.40 c |

| Variables | TPC | TFC | Antiradical Activity | Antioxidant Activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPC | 1 | 0.8592 | 0.5348 | 0.8097 |

| TFC | 1 | 0.6771 | 0.8532 | |

| Antiradical Activity | 1 | 0.8389 | ||

| Antioxidant Activity | 1 |

| Regions (cm−1) | Orange | Lemon | Red Grapefruit | Yellow Grapefruit | Clementine | Kumquat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3630 | - | 0.010 ± 0.002 | - | - | - | - |

| 3525 | - | - | - | - | 0.017 ± 0.003 | - |

| 3414 | - | - | - | - | 0.030 ± 0.006 | - |

| 3300 | 0.789 ± 0.005 a | 0.049 ± 0.005 b | 0.052 ± 0.004 b | 0.071 ± 0.005 c | 0.022 ± 0.003 d | 0.810 ± 0.019 a |

| 3078 | - | 0.064 ± 0.006 a | - | 0.031 ± 0.001 b | - | - |

| 3010 | - | 0.016 ± 0.003 a | 0.021 ± 0.001 b | 0.023 ± 0.002 b | - | - |

| 2962 | - | 0.126 ± 0.015 a | 0.077 ± 0.005 b | 0.092 ± 0.004 c | - | - |

| 2922 | 0.255 ± 0.024 a | 0.483 ± 0.022 b | 0.414 ± 0.031 c | 0.388 ± 0.018 c | 0.299 ± 0.016 d | 0.168 ± 0.005 e |

| 2850 | 0.085 ± 0.002 a | - | 0.104 ± 0.001 b | 0.034 ± 0.004 c | 0.108 ± 0.010 b | - |

| 1730 | 0.046 ± 0.006 a | 0.116 ± 0.006 b | 0.160 ± 0.019 c | 0.149 ± 0.011 c | 0.094 ± 0.007 d | 0.119 ± 0.014 b |

| 1643 | - | 0.046 ± 0.005 a | 0.076 ± 0.003 b | 0.055 ± 0.004 c | 0.298 ± 0.011 d | 0.118 ± 0.011 e |

| 1600 | 0.237 ± 0.022 a | 0.255 ± 0.024 a | 0.199 ± 0.017 b | 0.141 ± 0.007 c | 0.283 ± 0.008 d | - |

| 1517 | 0.024 ± 0.002 a | 0.076 ± 0.005 b | 0.018 ± 0.003 c | 0.023 ± 0.004 ac | 0.211 ± 0.007 d | 0.023 ± 0.003 ac |

| 1439 | - | 0.228 ± 0.022 a | 0.200 ± 0.023 a | 0.200 ± 0.021 a | 0.088 ± 0.008 b | - |

| 1400 | 0.064 ± 0.004 a | - | - | - | 0.028 ± 0.002 b | 0.049 ± 0.002 c |

| 1370–1360 | 0.023 ± 0.003 a | 0.093 ± 0.007 b | 0.064 ± 0.004 c | 0.064 ± 0.005 c | 0.051 ± 0.003 d | 0.032 ± 0.003 e |

| 1330 | - | 0.013 ± 0.001 a | - | 0.018 ± 0.002 b | - | - |

| 1300 | - | - | - | - | 0.050 ± 0.005 | - |

| 1280–1274 | - | 0.049 ± 0.003 a | - | - | 0.137 ± 0.004 b | - |

| 1240 | 0.045 ± 0.003 a | 0.064 ± 0.003 b | 0.082 ± 0.003 c | 0.105 ± 0.004 d | 0.078 ± 0.007 c | 0.040 ± 0.004 a |

| 1200 | - | 0.052 ± 0.002 a | - | - | 0.087 ± 0.006 b | - |

| 1182 | - | - | - | - | 0.061 ± 0.002 | - |

| 1147 | - | 0.055 ± 0.008 a | - | - | 0.109 ± 0.006 b | - |

| 1093 | - | 0.081 ± 0.009 a | - | - | 0.123 ± 0.005 b | 0.034 ± 0.004 c |

| 1055 | - | 0.044 ± 0.003 a | - | 0.062 ± 0.005 b | 0.096 ± 0.010 c | - |

| 1016–1012 | 0.545 ± 0.042 a | 0.538 ± 0.021 a | 0.636 ± 0.026 b | 0.610 ± 0.039 b | 0.228 ± 0.009 c | 0.117 ± 0.009 d |

| 975 | - | 0.053 ± 0.003 a | - | - | 0.142 ± 0.005 b | 0.077 ± 0.005 c |

| 920 | 0.019 ± 0.002 ab | 0.018 ± 0.002 ab | 0.021 ± 0.002 a | 0.020 ± 0.005 a | 0.015 ± 0.002 b | 0.051 ± 0.004 c |

| 890 | 0.016 ± 0.003 a | 0.188 ± 0.016 b | 0.126 ± 0.010 c | 0.149 ± 0.031 c | - | 0.016 ± 0.002 a |

| 842 | - | - | - | - | 0.035 ± 0.001 | - |

| 812 | 0.017 ± 0.002 a | 0.024 ± 0.002 b | 0.024 ± 0.002 b | 0.018 ± 0.003 a | 0.102 ± 0.003 c | 0.021 ± 0.002 ab |

| 765 | 0.024 ± 0.004 a | 0.014 ± 0.001 b | 0.014 ± 0.001 b | 0.022 ± 0.003 a | 0.077 ± 0.004 c | 0.018 ± 0.002 d |

| 738 | - | - | - | - | 0.061 ± 0.004 | - |

| 669 | - | - | - | - | 0.015 ± 0.001 | - |

| 623 | 0.012 ± 0.001 a | - | - | 0.015 ± 0.002 a | 0.051 ± 0.002 b | - |

| 586 | 0.008 ± 0.002 a | 0.018 ± 0.002 b | 0.007 ± 0.001 a | 0.008 ± 0.001 a | 0.035 ± 0.005 c | 0.011 ± 0.001 d |

| 530–524 | 0.016 ± 0.003 a | 0.029 ± 0.004 bd | 0.009 ± 0.001 c | 0.024 ± 0.003 b | 0.032 ± 0.005 d | 0.009 ± 0.002 c |

| Regions (cm−1) | Band | Compounds |

|---|---|---|

| 3630–3410 | ν (OH) | Pectin, phenolic compounds |

| 3300 | ν (OH) | Water, carbohydrates (pectin and cellulose), organic acids, polyphenols |

| 2962–2922 | ν (C(sp3)-H) | Carbohydrates, carboxylic acids, flavonoid glycosides |

| 2850 | ||

| 1730 | ν (C=O) | Organic acids, esters, cutin |

| 1643 | δ (OH) | Polyphenols, carbohydrates, organic acids, water |

| ν (C=O) | Flavonoids | |

| 1600 | ν (C−C) | Pectin, aromatic compounds |

| ν (COOH) | Pectin | |

| 1517 | ν (C=C-C) (aromatic) | Phenolic compounds |

| 1439–1400 | δ (C-H) | Carbohydrates (e.g., pectin) |

| δ (O-H) | ||

| ν (COOH) | ||

| 1370–1360 | ν (CH3) | Organic acids, carbohydrates |

| ν (C-OOH) | ||

| 1330–1330 | δ (C-H) | Polysaccharides (e.g., cellulose) |

| 1280–1274 | δ (O-H) | Cutin, polysaccharides |

| ν (C-N) | Proteins (amide III band) | |

| δ (N-H) | ||

| δ (O=C-N) | ||

| 1240 | ν (C-O) | Polyphenols, carbohydrates |

| ν (C=C) | Aromatic polyphenols | |

| 1182 | ν (C-O-C) | Cellulose |

| ν (C-C) | ||

| 1147 | ν (C-O-C) | Cutin, pectin, cellulose |

| 1100–1090 | ν (C-O) | Pectin, polysaccharides |

| ν (C-C) | ||

| 1055 | δ (C-O) | Carbohydrates (cellulose, sucrose) |

| ν (C-OH) | ||

| 1016–1012 | ν (C-O) | Pectin, cellulose |

| ν (C-C) | ||

| δ (C-OH) | Carboxylic acids, alcohols, carbohydrates | |

| δ (O-CH) | Pectin, polysaccharides | |

| 975 | δ (trans C-H) | Carotenoids |

| 920 | δ (C=C) | Alkenes |

| δ (C-H) | Benzene ring of phenols | |

| 890–840 | δ (C-H) | Para (1,4)-substituted aromatic rings |

| 812 | C-H | Aromatic ring of phenols |

| 765 | δ (OH) | C-OH group |

| δ (C-H) | Ortho (1,2)-substituted aromatic rings | |

| 738 | δ (cis C-H) | Carotenoids |

| 623 | δ (O-H) | Pectin |

| 586 | δ (C-H) | Polyphenols and flavonoids |

| 530–524 | δ (C-O-C) | Glycosidic bond of pectin |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aouant, K.; Christodoulou, P.; Tsiaka, T.; Strati, I.F.; Cavouras, D.; Sinanoglou, V.J. Implementation of Instrumental Analytical Methods, Image Analysis and Chemometrics for the Comparative Evaluation of Citrus Fruit Peels. Foods 2025, 14, 4115. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234115

Aouant K, Christodoulou P, Tsiaka T, Strati IF, Cavouras D, Sinanoglou VJ. Implementation of Instrumental Analytical Methods, Image Analysis and Chemometrics for the Comparative Evaluation of Citrus Fruit Peels. Foods. 2025; 14(23):4115. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234115

Chicago/Turabian StyleAouant, Konstantinos, Paris Christodoulou, Thalia Tsiaka, Irini F. Strati, Dionisis Cavouras, and Vassilia J. Sinanoglou. 2025. "Implementation of Instrumental Analytical Methods, Image Analysis and Chemometrics for the Comparative Evaluation of Citrus Fruit Peels" Foods 14, no. 23: 4115. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234115

APA StyleAouant, K., Christodoulou, P., Tsiaka, T., Strati, I. F., Cavouras, D., & Sinanoglou, V. J. (2025). Implementation of Instrumental Analytical Methods, Image Analysis and Chemometrics for the Comparative Evaluation of Citrus Fruit Peels. Foods, 14(23), 4115. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234115