Effect of Polygonatum cyrtonema Flour Addition on the Rheological Properties, Gluten Structure Characteristics of the Dough and the In Vitro Digestibility of Steamed Bread

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Steamed Bread

2.3. Thermo-Mechanical Behavior of Blended Flours in the Mixolab

2.4. Thermodynamic Properties Analysis

2.5. Gelatinization Properties Analysis

2.6. Microstructural Analysis of Dough

2.7. Water Distribution Analysis

2.8. Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Spectroscopy

2.9. Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate–Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE)

2.10. Free Thiol and Disulfide Bond Analysis

2.11. Non-Covalent Interactions

2.12. UV–Vis Absorption Spectra

2.13. Intrinsic Fluorescence Spectra

2.14. Physical Properties of Steamed Bread

2.14.1. Texture Profile and Specific Volume Analysis

2.14.2. Color Difference Analysis

2.14.3. Pore Structure Analysis

2.15. In Vitro Antioxidant Capacity Assay

2.15.1. DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity

2.15.2. ABTS Radical Scavenging Activity

2.16. In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion Simulation

2.17. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

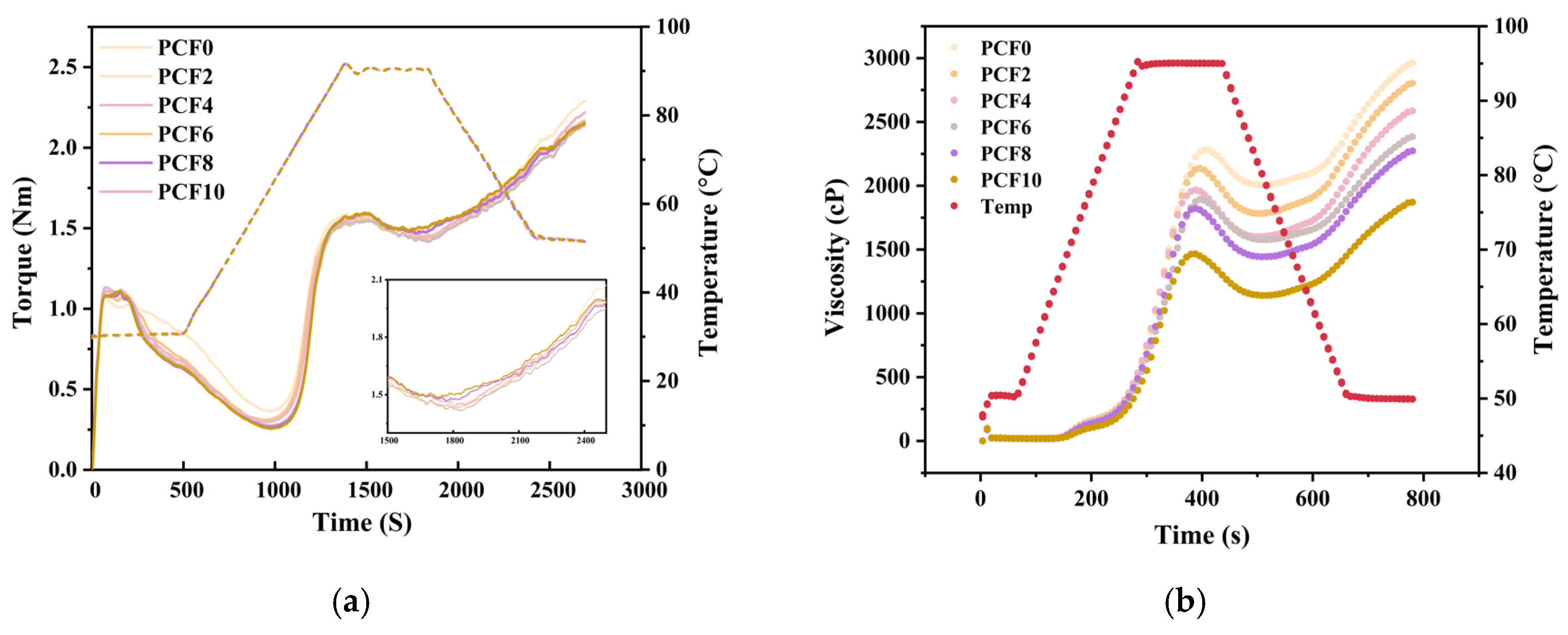

3.1. Polygonatum Cyrtonema Flour Effects on Wheat Flour Farinograph Properties

3.2. Thermal Characteristic Analysis

3.3. Analysis of Pasting Properties

3.4. Scanning Electron Microscopy

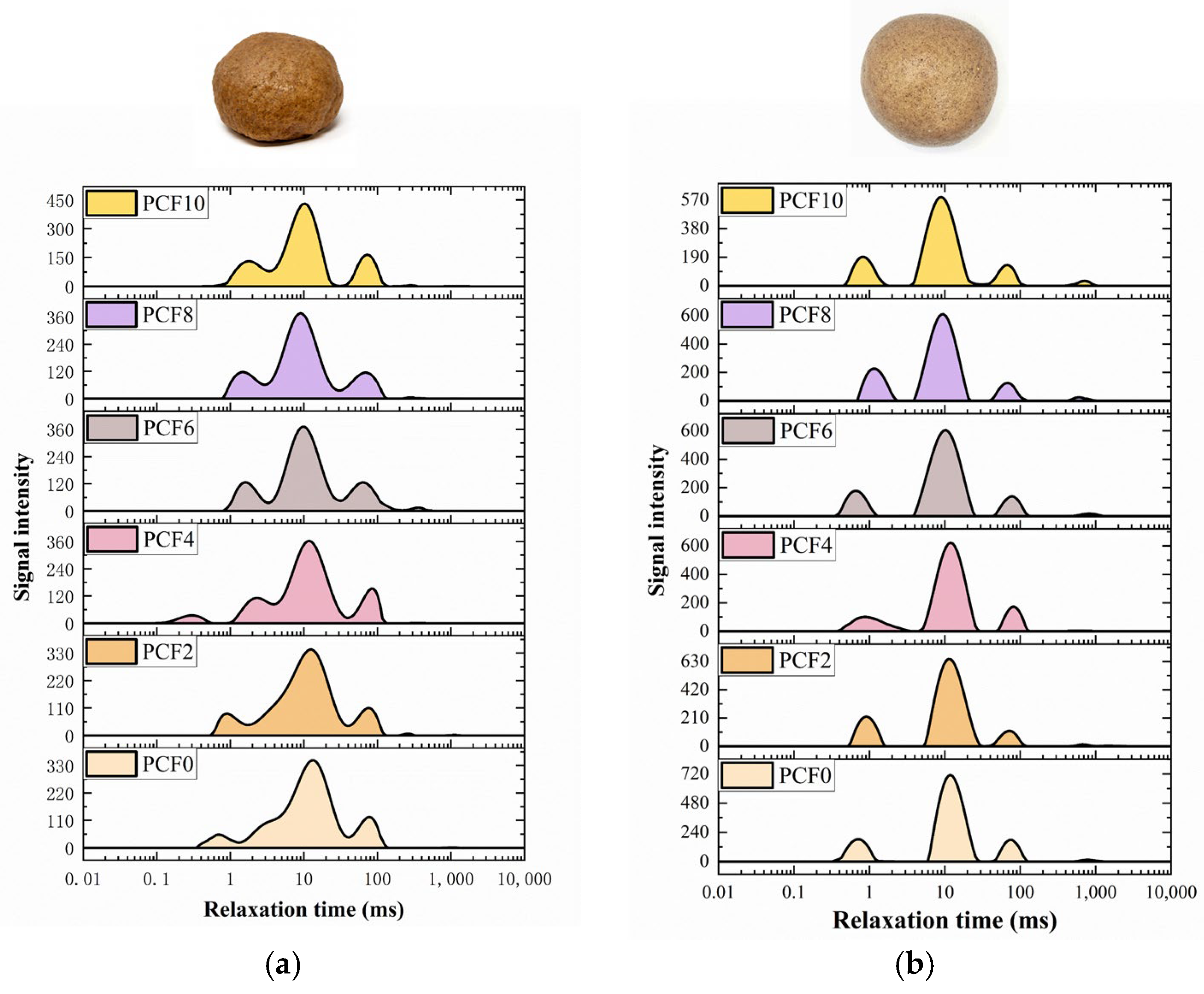

3.5. Water Distribution State

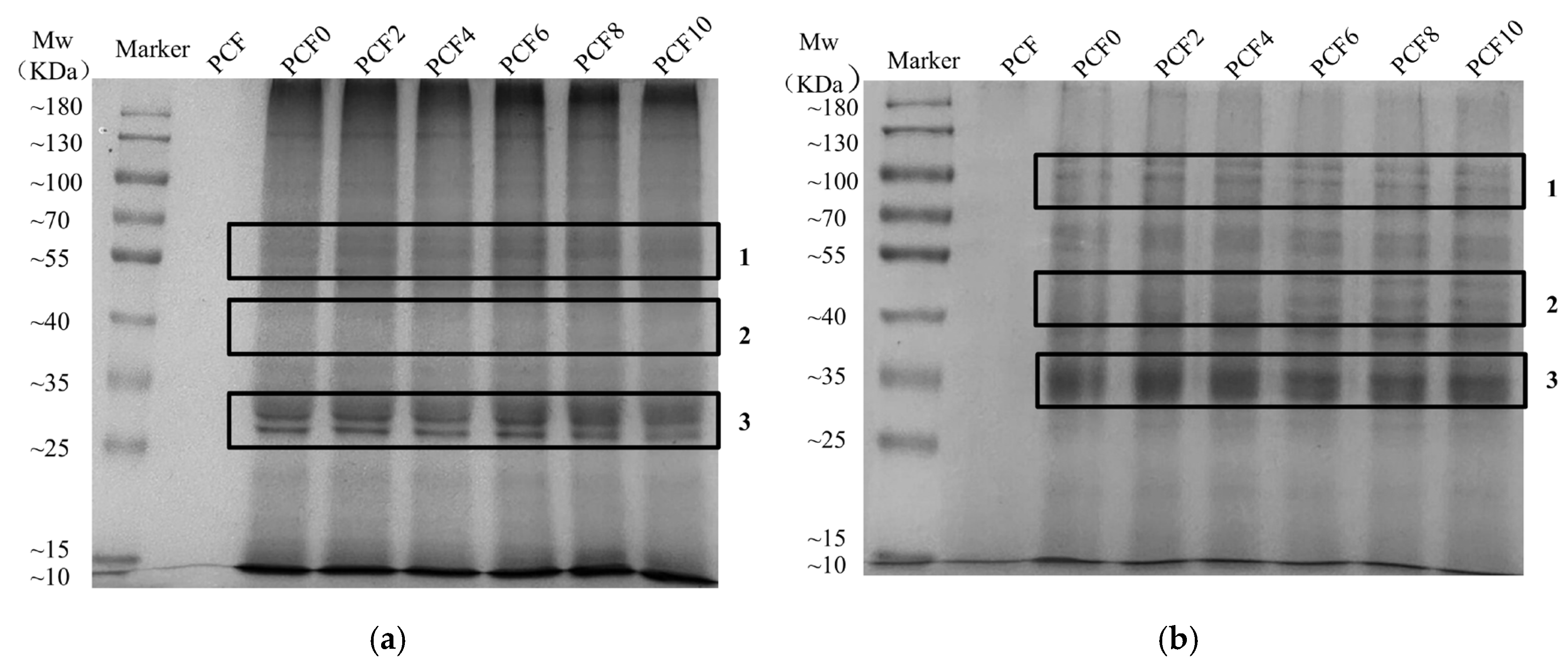

3.6. Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate–Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis

3.7. FT-IR

3.8. SH and S-S Contents

3.9. Non-Covalent Interactions

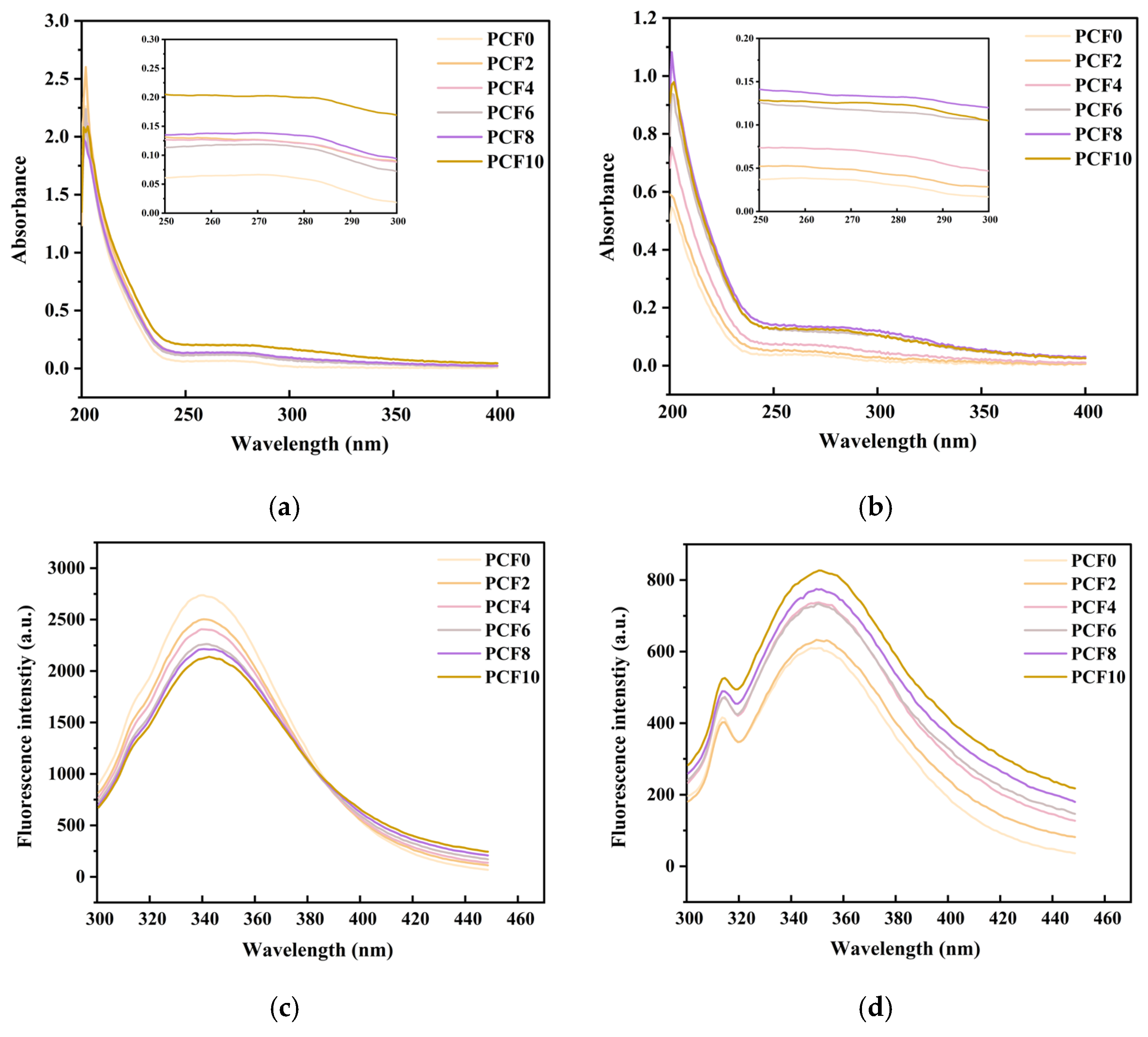

3.10. UV–Visible Absorption Spectroscopy

3.11. Fluorescence Spectroscopic Analysis

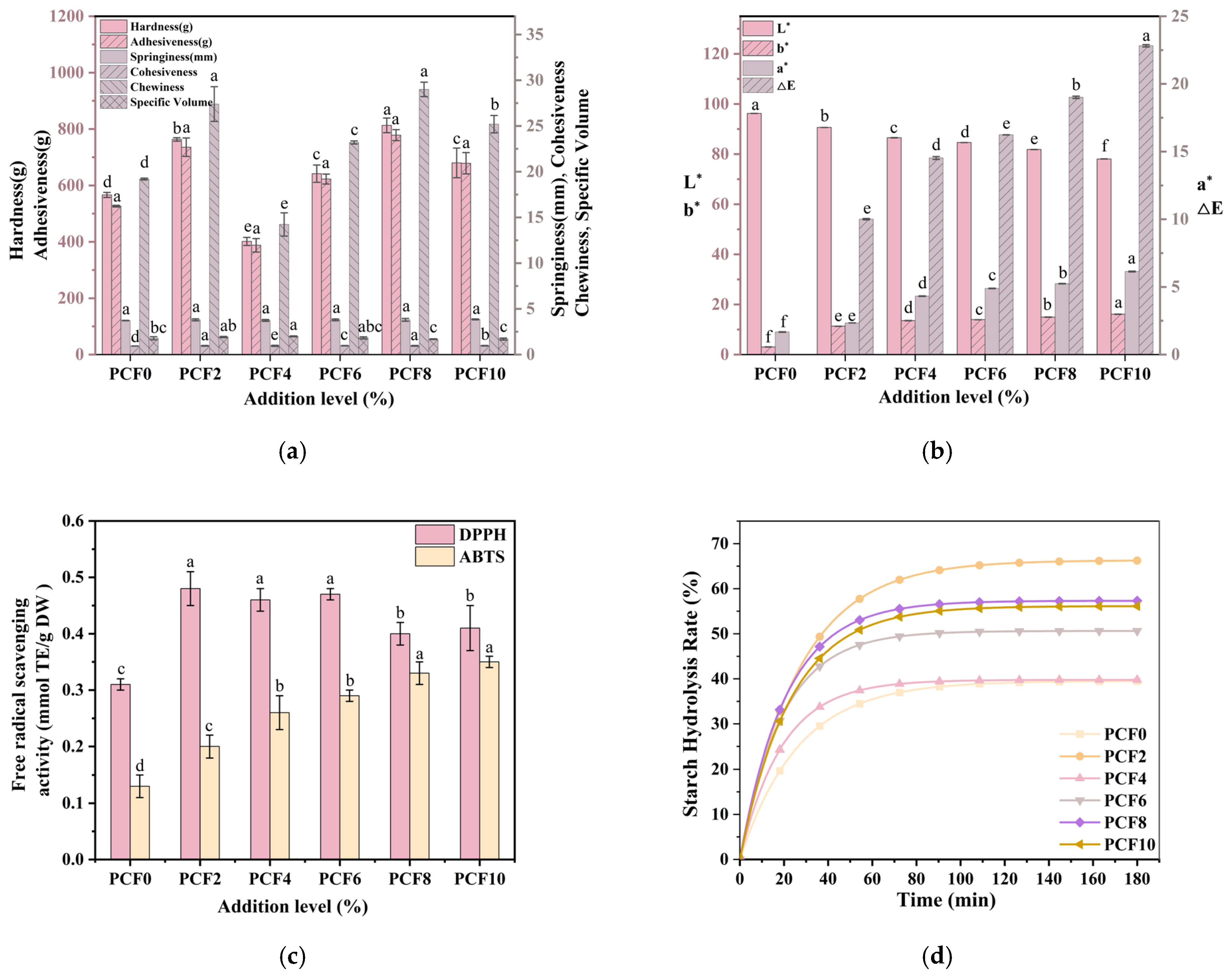

3.12. Texture Profile and Loaf Specific Volume

3.13. Color Difference

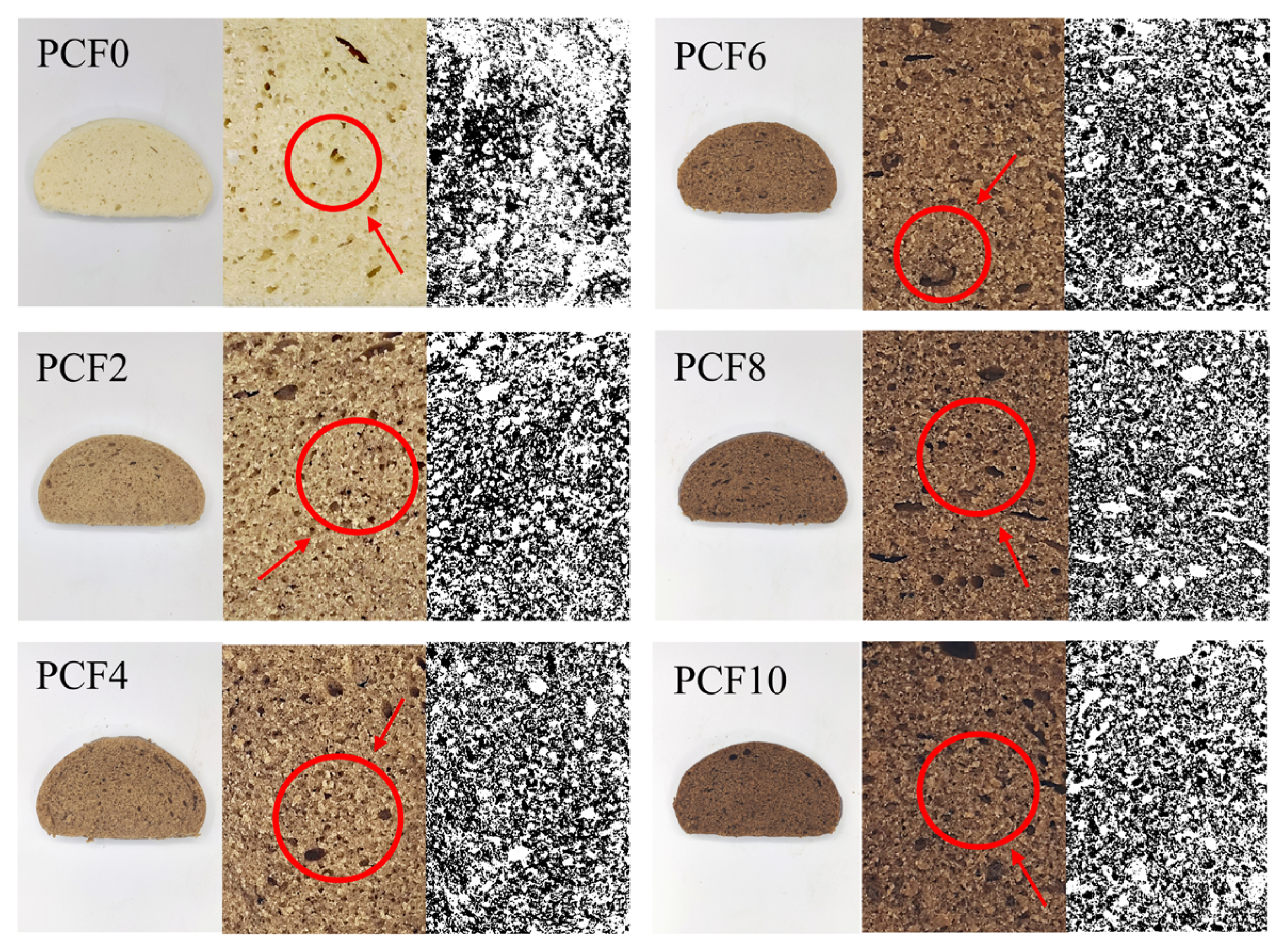

3.14. Pore Analysis of Steamed Bread Crumb

3.15. Antioxidant Capacity

3.16. In Vitro Digestion Analysis

3.17. Multiscale Mechanism of Polygonatum cyrtonema Flour in Enhancing Dough Quality

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PCF | Polygonatum cyrtonema flour |

| DSC | Differential Scanning Calorimetry |

| RVA | Rapid Visco Analyzer |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| FT-IR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| SDS-PAGE | Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate–Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis |

| LF-NMR | Low-Field Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| DNTB | 5,5′-Dithiobis 2-nitrobenzoic acid |

| DTT | Dithiothreitol |

| TCA | Trichloroacetic acid |

| DNS | 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid |

| UV–Vis | Ultraviolet–Visible Absorption Spectroscopy |

| DPPH | 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| ABTS | 2,2′-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) |

References

- Han, M.; Zhou, J.; Wang, J.; Ivanistau, A.; Yang, Q.; Feng, B. Wheat Improves the Quality of Coarse Cereals Steamed Bread by Changing the Gluten Network. Appl. Food Res. 2025, 5, 101040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Wang, H.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Romanova, N.; Ivanistau, A.; Yang, Q.; Feng, B. Gluten-Starch Microstructure Analysis Revealed the Improvement Mechanism of Triticeae on Broomcorn Millet (Panicum Miliaceum L.). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 262, 130222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Sun, H.; Mu, T. Effects of Sweet Potato Leaf Powder on Sensory, Texture, Nutrition, and Digestive Characteristics of Steamed Bread. Food Process. Preserv. 2022, 46, e16697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Chen, N.; Yu, Z.; Sun, Q.; He, Q.; Zeng, W. Effect of Tea Polyphenols on the Quality of Chinese Steamed Bun and the Action Mechanism. J. Food Sci. 2022, 87, 1500–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Tan, C.; Li, H.; Wang, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Ning, C.; Li, W.; Guo, C. Extraction, Purification, Structural Characterization, Biological Activity, Structure-Activity Relationship, and Applications of Polysaccharides Derived from Polygonatum Sibiricum: A Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 161, 105038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Gao, W.; Mao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Mao, J.; Sha, R. The Polysaccharides from Mixed-Culture Fermentation of Huangjing: Extraction, Structural Analysis and Anti-Lipid Activity. LWT 2025, 233, 118537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-L.; Ma, R.-H.; Zhang, F.; Ni, Z.-J.; Thakur, K.; Wang, S.; Zhang, J.-G.; Wei, Z.-J. Evolutionary Research Trend of Polygonatum Species: A Comprehensive Account of Their Transformation from Traditional Medicines to Functional Foods. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 3803–3820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Xie, B.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Ju, J.; Ma, Y. A Comprehensive Review on the Potential Applications of Medicine Polygonatum Species in the Food Sector. Food Biosci. 2024, 60, 104116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.; Chen, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Yang, S.; Zhu, G. Polysaccharides from Polygonatum Cyrtonema Hua Prevent Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Behaviors in Mice: Mechanisms from the Perspective of Synaptic Injury, Oxidative Stress, and Neuroinflammation. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 319, 117165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ma, S.; Li, L.; Huang, J. Synergistic Fermentation of Lactobacillus Plantarum and Saccharomyces Cerevisiae to Improve the Quality of Wheat Bran Dietary Fiber-Steamed Bread. Food Chem. X 2022, 16, 100528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.R.; Kim, M.-R.; Ryu, A.-R.; Bae, J.-E.; Choi, Y.-S.; Lee, G.B.; Choi, H.-D.; Hong, J.S. Comparison of Rheological Properties between Mixolab-Driven Dough and Bread-Making Dough under Various Salt Levels. Food Sci Biotechnol 2023, 32, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, B.; Zhang, W.-G.; Zhang, J.; Yang, X.-J.; Xu, H.-D. Effect of Thermal Treatment on the Internal Structure, Physicochemical Properties and Storage Stability of Whole Grain Highland Barley Flour. Foods 2022, 11, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Wang, X.; Gu, Z.; Hong, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, C.; Ban, X. Effects of Different Gelatinization Degrees of Starch in Potato Flour on the Quality of Steamed Bread. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 209, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, W.; Li, C.; Xu, Y.; Ding, X.; Zhou, X. Physicochemical Properties and Nutritional Quality of Pre-Fermented Red Bean Steamed Buns as Affected by Freeze-Thaw Cycling. Int. J. Food Prop. 2022, 25, 748–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.-F.; Tao, H.; Wang, H.-L.; Xu, X.-M. Impact of Water Soluble Arabinoxylan on Starch-Gluten Interactions in Dough. LWT 2023, 173, 114289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yang, L.; Guan, E.; Bian, K. Investigation of the Behavior of Wheat Flour Dough under Different Sheeting-Resting Cycles and Temperatures: Large Deformation Rheology and Gluten Molecular Interactions. Food Chem. X 2025, 27, 102366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoder, R.M.; Yin, T.; Liu, R.; Xiong, S.; You, J.; Hu, Y.; Huang, Q. Effects of Nano Fish Bone on Gelling Properties of Tofu Gel Coagulated by Citric Acid. Food Chem. 2020, 332, 127401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Xiong, W.; Peng, D.; He, Y.; Zhou, P.; Li, J.; Li, B. Effects of Thermal Sterilization on Soy Protein Isolate/Polyphenol Complexes: Aspects of Structure, In Vitro Digestibility and Antioxidant Activity. Food Res. Int. 2018, 112, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pasquale, I.; Verni, M.; Verardo, V.; Gómez-Caravaca, A.M.; Rizzello, C.G. Nutritional and Functional Advantages of the Use of Fermented Black Chickpea Flour for Semolina-Pasta Fortification. Foods 2021, 10, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Pang, L.; Bao, L.; Ye, X.; Lu, G. Effect of White Kidney Bean Flour on the Rheological Properties and Starch Digestion Characteristics of Noodle Dough. Foods 2022, 11, 3680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Gujral, H.S. Mixolab Thermo-Mechanical Behaviour of Millet Flours and Their Cookie Doughs, Flour Functionality and Baking Characteristics. J. Cereal Sci. 2024, 116, 103866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liang, Y.; Guo, P.; Liu, M.; Chen, Z.; Qu, Z.; He, B.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J. Understanding the Influence of Curdlan on the Quality of Frozen Cooked Noodles During the Cooking Process. LWT 2022, 161, 113382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, F.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Teng, C.; Wang, C.; Li, X. Effects of Different Molecular Weight Water-Extractable Arabinoxylans on the Physicochemical Properties and Structure of Wheat Gluten. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, L.; Luo, D.; Wei, Y.; Li, P.; Yue, C.; Wang, L.; Bai, Z. Effect of Phosphorylation of Long-chain Inulin on the Rheological Properties of Wheat Flour Doughs with Different Gluten. Int. J. Food Sci. Tech. 2024, 59, 2349–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, X.; Yue, C.; Luo, D.; Li, P.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wang, L.; Bai, Z. Effects of Natural Inulin on the Rheological, Physicochemical and Structural Properties of Frozen Dough during Frozen Storage and Its Mechanism. LWT 2023, 184, 114973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.-M.; Li, Y.; Zou, J.-H.; Guo, S.-Y.; Wang, F.; Yu, P.; Su, X.-J. Influence of Adding Chinese Yam (Dioscorea Opposita Thunb.) Flour on Dough Rheology, Gluten Structure, Baking Performance, and Antioxidant Properties of Bread. Foods 2020, 9, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Liang, Z.; Wang, S.; Gao, H.; Zeng, J.; Liu, X.; Li, W.; Liang, W. Modulating the Highland Barley Hordein/Glutelin Ratio Can Improve Reconstituted Fermented Dough Characteristics to Promote Chinese Mantou Quality. Food Res. Int. 2025, 199, 115396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Guo, J.; Zhang, C.; Li, X.; Geng, M.; Lan, H.; Luo, D.; Han, S. Effects of Red Kidney Bean Polysaccharide on the Physicochemical Properties of Frozen Dough and the Resulting Steamed Bread Quality. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 16, 101063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.-W.; Ma, M.; Zhang, H.-H.; Li, M.; Sun, Q.-J. Progressive Study of the Effect of Superfine Green Tea, Soluble Tea, and Tea Polyphenols on the Physico-Chemical and Structural Properties of Wheat Gluten in Noodle System. Food Chem. 2020, 308, 125676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Wraikat, M.; Hou, C.; Zhao, G.; Lu, H.; Zhang, H.; Lei, Y.; Ali, Z.; Li, J. Degraded Polysaccharide from Lycium Barbarum L. Leaves Improve Wheat Dough Structure and Rheology. LWT 2021, 145, 111372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Huang, J.; Mei, X.; Sui, Y.; Li, S.; Zhu, Z. Noncovalent Conjugates of Anthocyanins to Wheat Gluten: Unraveling Their Microstructure and Physicochemical Properties. Foods 2024, 13, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Guo, J.; Niu, M.; Lu, C.; Wang, P.; Luo, D. Mitigating Effect of Fucoidan Versus Sodium Alginate on Quality Degradation of Frozen Dough and Final Steamed Bread. Food Chem. X 2024, 23, 101608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Guo, X.; Yang, Z.; Xing, J.; Zhu, K. Combined Effect of NaCl and Resting on Dough Rheology of Chinese Traditional Hand-stretched Dried Noodles and the Underlying Mechanism. Cereal Chem. 2021, 98, 774–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Peng, R.; Tian, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Liang, Y.; Wang, J. Impacts of Konjac Glucomannan on the Physicochemical and Compositional Properties of Gluten with Different Strengths. LWT 2025, 225, 117949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kłosok, K.; Welc, R.; Szymańska-Chargot, M.; Nawrocka, A. Phenolic Acids-Induced Aggregation of Gluten Proteins. Structural Analysis of the Gluten Network Using FT-Raman Spectroscopy. J. Cereal Sci. 2022, 107, 103503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Jiang, L.; Qi, M.; Li, L.; Xu, M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, D.; Wang, C.; Chen, S.; Li, H. Study of Ultrasonic Treatment on the Structural Characteristics of Gluten Protein and the Quality of Steamed Bread with Potato Pulp. Ultrason. Sonochemistry 2023, 92, 106281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Sun, H.; Ma, M.; Mu, T. Effects of Dietary Fibres, Polyphenols and Proteins on the Estimated Glycaemic Index, Physicochemical, Textural and Microstructural Properties of Steamed Bread. Int. J. Food Sci. Tech. 2024, 59, 4041–4052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, S.; Geng, S.; Liu, C.; Ma, H.; Liu, B. Effects of Tartary Buckwheat Bran Flour on Dough Properties and Quality of Steamed Bread. Foods 2021, 10, 2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, M.; Wu, Y.; Wang, G.; Liu, G.; Yar, M.S.; Li, D.; Xie, C.; Yang, R.; Jiang, D.; Wang, P. Insight into the Effect of Wheatgrass Powder on Steamed Bread Properties: Impacts on Gluten Polymerization and Starch Gelatinization Behavior. Food Chem. X 2025, 26, 102306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, X. Effects of Coarse Cereals on Dough and Chinese Steamed Bread—A Review. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1186860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Sun, F.; Li, X.; Wang, P.; Sun, J.; Zeng, J.; Wang, C.; Hu, W.; Chang, J.; et al. Tannins Improve Dough Mixing Properties Through Affecting Physicochemical and Structural Properties of Wheat Gluten Proteins. Food Res. Int. 2015, 69, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-C.; Yang, Z.; Guo, X.-N.; Zhu, K.-X. Effects of Insoluble Dietary Fiber and Ferulic Acid on the Quality of Steamed Bread and Gluten Aggregation Properties. Food Chem. 2021, 364, 130444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Kang, Z.; Zhao, D.; He, M.; Ning, F. Effect of Green Wheat Flour Addition on the Dough, Gluten Properties, and Quality of Steamed Bread. Food Process. Preserv. 2022, 46, e16827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, S.; Tao, P.; Yu, Y.; Wu, W.; Li, Y.; Chen, G.; Si, J.; Yang, H. Effect of Polygonatum Cyrtonema Hua Polysaccharides on Gluten Structure, In Vitro Digestion and Shelf-Life of Fresh Wet Noodle. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 279, 135475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Guo, W.; Liu, C.; Wang, X.; Hong, J.; Liu, M.; Sun, B.; Zheng, X. Effect of Polysaccharide on Rheology of Dough, Microstructure, Physicochemical Properties and Quality of Fermented Hollow Dried Noodles. LWT 2024, 200, 116214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterworth, P.J.; Warren, F.J.; Grassby, T.; Patel, H.; Ellis, P.R. Analysis of Starch Amylolysis Using Plots for First-Order Kinetics. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 87, 2189–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Addition Level (%) | TO (°C) | TP (°C) | TC (°C) | ∆H (J/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCF0 | 58.65 ± 0.45 a | 63.19 ± 0.35 b | 67.85 ± 0.35 d | 5.66 ± 0.77 a |

| PCF2 | 58.67 ± 0.11 a | 63.28 ± 0.01 b | 68.08 ± 0.02 cd | 4.75 ± 0.47 a |

| PCF4 | 59.01 ± 0.18 a | 63.78 ± 0.24 a | 68.47 ± 0.04 bc | 5.19 ± 0.76 a |

| PCF6 | 59.49 ± 0.86 a | 64.11 ± 0.02 a | 69.32 ± 0.30 a | 7.44 ± 2.65 a |

| PCF8 | 59.14 ± 0.17 a | 64.03 ± 0.10 a | 68.90 ± 0.11 ab | 5.87 ± 0.12 a |

| PCF10 | 59.19 ± 0.21 a | 63.96 ± 0.04 a | 68.77 ± 0.18 b | 5.34 ± 0.05 a |

| Addition Level (%) | RDS | SDS | RS | C∞/% | K/min−1 | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCF0 | 21.03 ± 0.54 d | 18.48 ± 0.79 c | 60.48 ± 1.26 a | 39.52 ± 1.26 d | 0.04 ± 0.0008 d | 0.999 |

| PCF2 | 25.79 ± 0.17 c | 14.00 ± 0.28 d | 60.22 ± 0.24 a | 39.78 ± 0.24 d | 0.05 ± 0.0008 a | 0.996 |

| PCF4 | 32.51 ± 0.71 b | 18.12 ± 1.39 c | 49.37 ± 0.70 b | 50.63 ± 0.70 c | 0.05 ± 0.0032 a | 0.998 |

| PCF6 | 35.26 ± 0.62 a | 22.06 ± 0.21 b | 42.68 ± 0.47 c | 57.32 ± 0.47 b | 0.05 ± 0.0008 b | 0.999 |

| PCF8 | 32.65 ± 0.66 b | 23.49 ± 0.49 b | 43.85 ± 0.96 c | 56.15 ± 0.96 b | 0.04 ± 0.0007 c | 0.998 |

| PCF10 | 35.09 ± 1.50 a | 31.23 ± 1.87 a | 33.68 ± 2.92 d | 66.32 ± 2.92 a | 0.04 ± 0.0015 d | 0.999 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bi, Z.; Yang, Y.; Yang, L.; Yang, C.; Dong, C.; Liu, Z.; Gong, Z.; Wang, R.; Yin, X. Effect of Polygonatum cyrtonema Flour Addition on the Rheological Properties, Gluten Structure Characteristics of the Dough and the In Vitro Digestibility of Steamed Bread. Foods 2025, 14, 4116. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234116

Bi Z, Yang Y, Yang L, Yang C, Dong C, Liu Z, Gong Z, Wang R, Yin X. Effect of Polygonatum cyrtonema Flour Addition on the Rheological Properties, Gluten Structure Characteristics of the Dough and the In Vitro Digestibility of Steamed Bread. Foods. 2025; 14(23):4116. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234116

Chicago/Turabian StyleBi, Zhangjie, Yuling Yang, Long Yang, Chao Yang, Changqing Dong, Zhipeng Liu, Zexuan Gong, Ruxin Wang, and Xuebin Yin. 2025. "Effect of Polygonatum cyrtonema Flour Addition on the Rheological Properties, Gluten Structure Characteristics of the Dough and the In Vitro Digestibility of Steamed Bread" Foods 14, no. 23: 4116. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234116

APA StyleBi, Z., Yang, Y., Yang, L., Yang, C., Dong, C., Liu, Z., Gong, Z., Wang, R., & Yin, X. (2025). Effect of Polygonatum cyrtonema Flour Addition on the Rheological Properties, Gluten Structure Characteristics of the Dough and the In Vitro Digestibility of Steamed Bread. Foods, 14(23), 4116. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234116