Characterization of Mutton Volatile Compounds in Youzhou Dark Goats and Local White Goats Using Flavoromics, Metabolomics, and Transcriptomics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals, Diets, and Feeding Management

2.2. Slaughtering, Pretreatment, and Sample Collection

2.3. Volatile Compound Analysis

2.3.1. Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME) Conditions

2.3.2. GC × GC Analysis Conditions

2.3.3. Mass Spectrum Conditions

2.3.4. Data Analysis

2.3.5. Flavoromics Analysis

2.4. Untargeted Metabolomics Analysis

2.4.1. Metabolites Extraction

2.4.2. Instrument Parameters

2.4.3. Bioinformatics Analysis

2.5. Transcriptome Analysis

2.5.1. RNA Extraction

2.5.2. Sequencing

2.5.3. RNA-Seq Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Types of Flavor Substances Identification and Sensory Flavor Characteristics

3.1.1. Identifying Types of Flavor Substances

3.1.2. Analysis of Sensory Flavor Characteristics

3.2. Multivariate Statistical Analysis

3.2.1. PCA of Volatile Compounds

3.2.2. OPLS-DA of Volatile Compounds

3.3. Analysis of Differential Volatile Compounds

3.4. Analysis of Differential Metabolites

3.5. Identification of Differential Genes and Functional Enrichment Analysis

3.5.1. Identification of DEGs

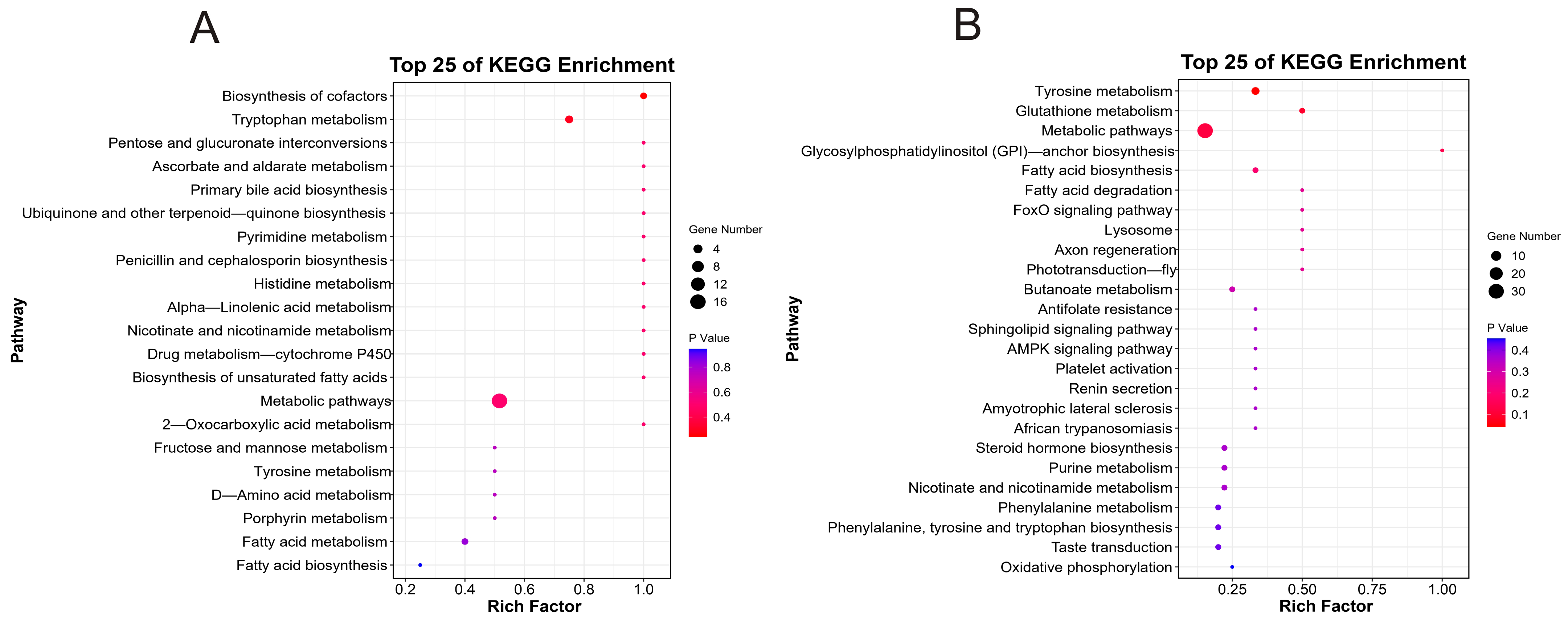

3.5.2. Functional Enrichment Analysis

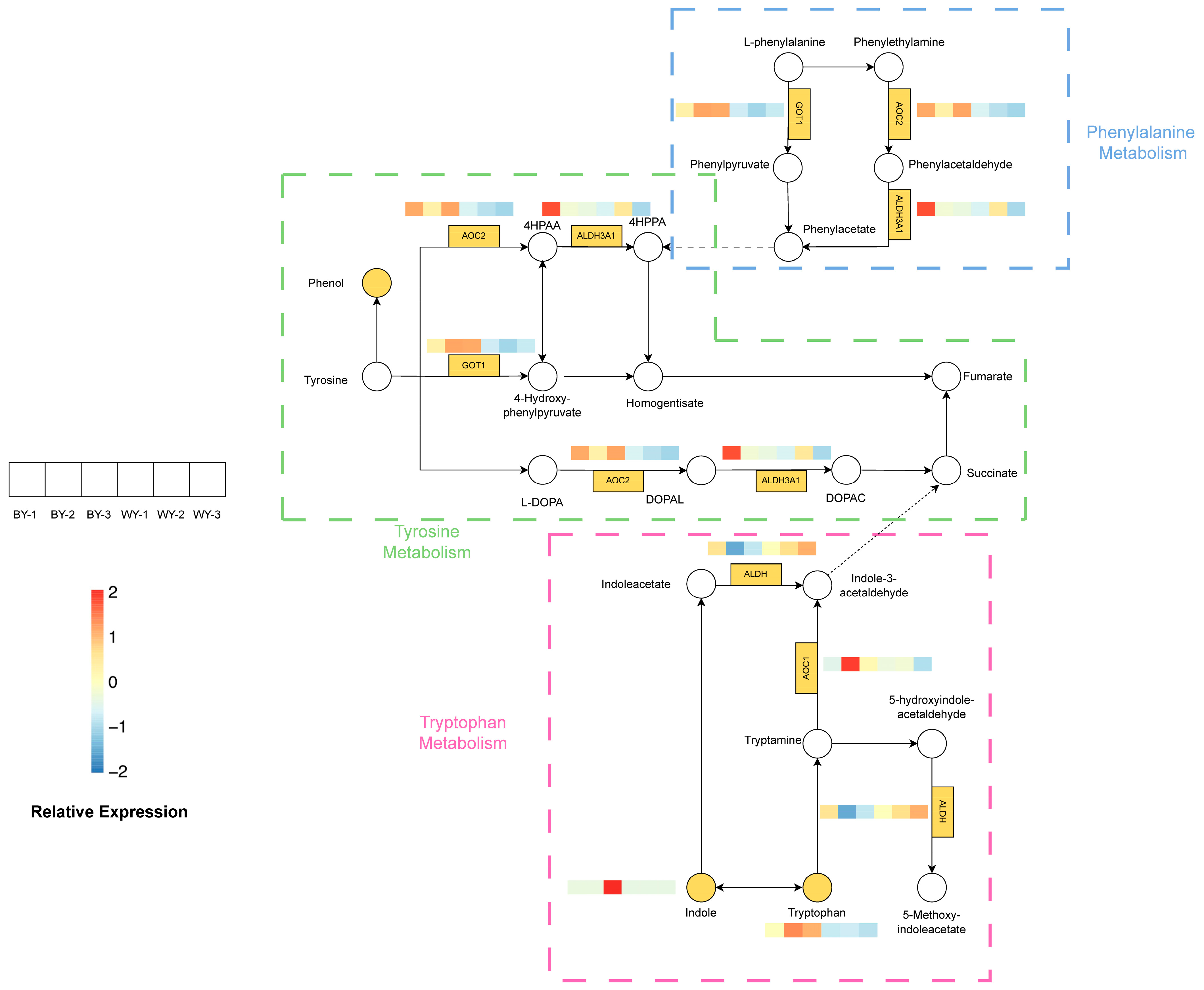

3.6. Analysis of the Tyrosine, Phenylalanine, and Tryptophan Metabolism Pathways

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arshad, M.S.; Sohaib, M.; Ahmad, R.S.; Nadeem, M.T.; Imran, A.; Arshad, M.U.; Kwon, J.; Amjad, Z. Ruminant meat flavor influenced by different factors with special reference to fatty acids. Lipids Health Dis. 2018, 17, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, J.; Diao, Q.; Zhao, J.; Wang, H.; Deng, K.; Qi, M.; Nie, M.; Zhang, N. Effects of rearing system on meat quality, fatty acid and amino acid profiles of Hu lambs. Anim. Sci. J. 2018, 89, 1178–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Retamal, J.; Morales, R. Influence of breed and feeding on the main quality characteristics of sheep carcass and meat: A review. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 2014, 74, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prache, S.; Schreurs, N.; Guillier, L. Review: Factors affecting sheep carcass and meat quality attributes. Animal 2022, 16 (Suppl. 1), 100330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Li, J.; Yuan, C.; Xi, B.; Yang, B.; Meng, X.; Guo, T.; Yue, Y.; Gao, Y.; Liu, J.; et al. Evaluation of mutton quality characteristics of Dongxiang Tribute Sheep based on membership function and gas chromatography and ion mobility spectrometry. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 852399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodacre, R.; Vaidyanathan, S.; Dunn, W.B.; Harrigan, G.G.; Kell, D.B. Metabolomics by numbers: Acquiring and understanding global metabolite data. Trends Biotechnol. 2004, 22, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintanilla-Casas, B.; Torres-Cobos, B.; Bro, R.; Guardiola, F.; Vichi, S.; Tres, A. The volatile metabolome—Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry approaches in the context of food fraud. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2025, 61, 101235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelli, V.; Belardo, A.; Timperio, A.M. From targeted quantification to untargeted metabolomics. In Metabolomics—Methodology and Applications in Medical Sciences and Life Sciences; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021; p. 96852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Chen, Y.P.; Blank, I.; Li, F.; Li, C.; Liu, Y. GC x GC-ToF-MS and GC-IMS based volatile profile characterization of the Chinese dry-cured hams from different regions. Food Res. Int. 2021, 142, 110222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Chen, S.; Nie, Y.; Xu, Y. Optimization of an intra-oral solid-phase microextraction (SPME) combined with comprehensive two-dimen sional gas chromatography-time-of-flight mass spectrometry (GC x GC-TOFMS) method for oral aroma compounds monitoring of Baijiu. Food Chem. 2022, 15, 132502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xu, R.; Tong, X.; Zeng, J.; Chen, M.; Lin, Z.; Cai, S.; Chen, Y.; Mo, D. Characterization of different meat flavor compounds in Guangdong small-ear spotted and Yorkshire pork using two-dimensional gas chromatography–time-of-flight mass spectrometry and multi-omics. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 169, 114010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Gao, H.; Fu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Song, G.; Jin, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, J.; Yin, Y.; Xu, K. Comprehensive characterization of the differences in metabolites, lipids, and volatile flavor compounds between Ningxiang and Berkshire pigs using multi-omics techniques. Food Chem. 2024, 457, 139807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Q.; Dong, K.; Wang, Q.; Huang, X.; Wang, G.; An, F.; Luo, Z.; Luo, P. Changes in volatile flavor of yak meat during oxidation based on multi-omics. Food Chem. 2022, 371, 131103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, L.; Chaohua, T.; Youyou, Y.; Ying, H.; Qingyu, Z.; Qing, M.; Xiangpeng, Y.; Fadi, L.; Junmin, Z. Characterization of meat quality traits, fatty acids and volatile compounds in Hu and Tan sheep. Front. Nutr. 2023, 14, 1072159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Cui, H.; Yuan, X.; Liu, L.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Ding, J.; Xiang, H.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; et al. Identification of the main aroma compounds in Chinese local chicken high-quality meat. Food Chem. 2021, 359, 29930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Qi, L.; Zhang, S.; Peng, H.; Lin, Z.; Zhang, X.; Nie, Q.; Luo, W. Metabolomic, lipidomic, and proteomic profiles provide insights on meat quality differences between Shitou and Wuzong geese. Food Chem. 2024, 438, 137967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Zheng, J.; Zhao, L.; Fan, C.; Zhao, Y. Integrated Metabolomics and Transcriptomics analyses reveal the candidate genes regulating the meat quality change by castration in Yudong Black Goats (Capra hircus). Genes 2023, 15, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Sun, L.; Lv, Y.; Liao, R.; Zhang, K.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, S.; Xu, J.; He, M.; Wu, C.; et al. Transcriptomic and metabolomic dissection of skeletal muscle of crossbred chongming white goats with different meat production performance. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, L.; Liu, H.; Si, W.; Feng, T.; Bai, B.; Lin, Y. Multi-omics analysis reveals the differences in meat quality and flavor among three breeds of white goats with geographical indication of China. Food Chem. X 2025, 31, 103204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Wang, G.; Jiang, J.; Li, J.; Fu, L.; Liu, L.; Li, N.; Zhao, J.; Sun, X.; Zhang, L.; et al. Comparative transcriptome and histological analyses provide insights into the prenatal skin pigmentation in goat (Capra hircus). Physiol. Genom. 2017, 49, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Niu, Q.; Jiang, J.; Wang, G.; Zhou, P.; Li, J.; Chen, C.; Liu, L.; Xu, L.; Ren, H. Identifying candidate genes for litter size and three morphological traits in Youzhou Dark Goats based on genome-wide SNP markers. Genes 2023, 14, 1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, C.; Sun, X.; Jiang, J.; Lv, S.; Ren, H.; Wang, G. Comparison analysis on muscle texture characteristics and fatty acid of Youzhou dark goats and local white goats. Chin. J. Anim. Nutr. 2024, 36, 5181–5191. [Google Scholar]

- Wehrens, R. Chemometrics with R: Multivariate Data Analysis in the Natural Sciences and Life Sciences; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Trimigno, A.; Münger, L.; Picone, G.; Freiburghaus, C.; Pimentel, G.; Vionnet, N.; Pralong, F.; Capozzi, F.; Badertscher, R.; Vergères, G. C–MS-based metabolomics and NMR spectroscopy investigation of food intake biomarkers for milk and cheese in serum of healthy humans. Metabolites 2018, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Wu, Y.; Liu, B.; Chen, R.; Qiao, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Q.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z. Analysis for different flavor compounds in mature milk from human and livestock animals by GCxGC-TOFMS. Food Chem. X 2023, 19, 100760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Ran, X.; Luo, F.; Lin, Q.; Defang, D.; Zeng, W.; Dong, J. Food bioactive small molecule databases: Deep boosting for the study of food molecular behaviors. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 66, 102499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Xie, M.; Jiang, Y.; Xiao, N.; Du, X.; Zhang, W.; Tosser-Klopp, G.; Wang, J.; Yang, S.; Liang, J.; et al. Sequencing and automated whole-genome optical mapping of the genome of a domestic goat (Capra hircus). Nat. Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Huber and S. Anders, Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wang, H.; Liang, Z.; Liu, J.; Yang, C.; Zhai, H.; Chen, A.; Lu, Z.; Gao, Y.; Ding, X.; et al. Characterization of flavor compounds in Chinese indigenous sheep breeds using Gas Chro-matography-Ion Mobility Spectrometry and Chemometrics. Foods 2024, 13, 2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, X.; Chen, D.; Deng, S. Use of relative odor activity value (ROAV) to link aroma profiles to volatile compounds: Application to fresh and dried eel (Muraenesox cinereus). Int. J. Food 2020, 23, 2257–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuishi, M.; Igeta, M.; Takeda, S.; Okitani, A. Sensory factors contributing to the identification of the animal species of meat. J. Food Sci. 2004, 69, S218–S220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Zhan, J.; Tang, X.; Li, T.; Duan, S. Characterization and identification of pork flavor compounds and their precursors in Chinese indigenous pig breeds by volatile profiling and multivariate analysis. Food Chem. 2022, 385, 132543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, Y.; Tang, C.; Yue, S.; Zhao, Q.; Li, F.; Zhang, J. Changes in lipids and aroma compounds in intramuscular fat from Hu sheep. Food Chem. 2022, 383, 132611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, H.; Liu, M.; Zhao, X.; Luo, H. Effect of Breed on the volatile compound precursors and odor profile attributes of lamb meat. Foods 2020, 9, 1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottram, D. Flavour formation in meat and meat products: A review. Food Chem. 1998, 62, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Cai, Y.; Liu, D.; Chen, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, M.; Chen, N.; Zhang, H. Analysis of flavor formation during production of Dezhou braised chicken using headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spec-trometry (HS-GC-IMS). Food Chem. 2022, 370, 130989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Qi, L.; Zhang, S.; Peng, H.; Lin, Z.; Zhang, X.; Nie, Q.; Luo, W. Comparative characterization of flavor precursors and volatiles in Chongming white goat of different ages by UPLC-MS/MS and GC-MS. Food Chem. X 2024, 24, 101929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayasena, D.D.; Ahn, D.U.; Nam, K.C.; Jo, C. Flavour chemistry of chicken meat: A review. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2013, 26, 732–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, A.; Osako, K.; Ohshima, T. SPME technique for analyzing headspace volatiles in fish miso, a Japanese fish meat-based fermented product. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2010, 74, 1770–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, J.; Lv, S.; Chen, C.; Jiang, J.; Sun, X.; Wang, G.; Ren, H. Characterization of Mutton Volatile Compounds in Youzhou Dark Goats and Local White Goats Using Flavoromics, Metabolomics, and Transcriptomics. Foods 2025, 14, 4114. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234114

Li J, Lv S, Chen C, Jiang J, Sun X, Wang G, Ren H. Characterization of Mutton Volatile Compounds in Youzhou Dark Goats and Local White Goats Using Flavoromics, Metabolomics, and Transcriptomics. Foods. 2025; 14(23):4114. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234114

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Jie, Shipeng Lv, Cancan Chen, Jing Jiang, Xiaoyan Sun, Gaofu Wang, and Hangxing Ren. 2025. "Characterization of Mutton Volatile Compounds in Youzhou Dark Goats and Local White Goats Using Flavoromics, Metabolomics, and Transcriptomics" Foods 14, no. 23: 4114. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234114

APA StyleLi, J., Lv, S., Chen, C., Jiang, J., Sun, X., Wang, G., & Ren, H. (2025). Characterization of Mutton Volatile Compounds in Youzhou Dark Goats and Local White Goats Using Flavoromics, Metabolomics, and Transcriptomics. Foods, 14(23), 4114. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234114