Jerked Beef: Chemical Composition and Desalting Techniques

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Determination of Desalting Techniques of Jerked Beef

2.2. Analysis of Sodium Content in Jerked Beef Samples

2.3. Jerked Beef Chemical Composition

2.3.1. Moisture Determination

2.3.2. Ashes

2.3.3. Protein

2.3.4. Lipids

2.3.5. Carbohydrates

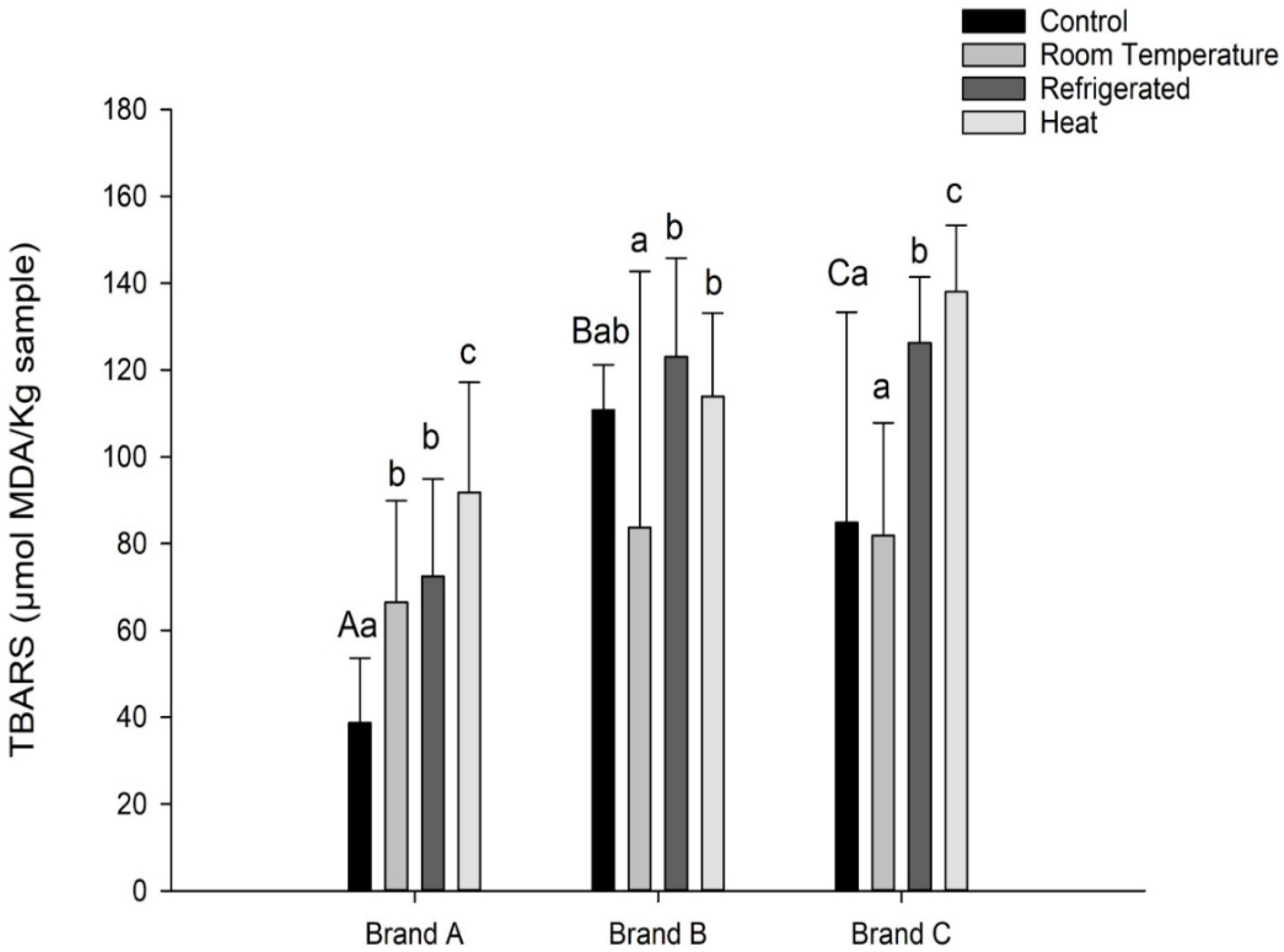

2.3.6. Lipid Oxidation

2.4. Determination of Titratable Acidity and pH

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Sodium Content in Jerked Beef Samples

3.2. Chemical Composition

3.3. Determination of Titratable Acidity and pH

4. Discussion

4.1. Analysis of Sodium Content in Jerked Beef Samples

4.2. Chemical Composition

4.3. Determination of Titratable Acidity and pH

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gonçalves, R.M.; Gonçalves, J.R.; Gonçalves, R.M.; Oliveira, R.R.d.; Oliveira, R.A.d.; Lage, M.E. Physical-Chemical Evaluation of and Heavy Metals Contents in Broiler and Beef Mechanically Deboned Meat (Mdm) Produced in The State of Goiás, Brazil. Ciênc. Anim. Bras. 2009, 10, 553–559. Available online: https://revistas.ufg.br/vet/article/view/1116 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Ribeiro, C.S.G.; Corção, M. The Consumption of Meat in Brazil: Between Socio-Cultural and Nutritional Values. Demetra Aliment. Nutr. Saúde 2013, 8, 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Magalhaes, D.R.; Maza, M.T.; Prado, I.N.; Fiorentini, G.; Kirinus, J.K.; Campo, M.M. An Exploratory Study of the Purchase and Consumption of Beef: Geographical and Cultural Differences between Spain and Brazil. Foods 2022, 11, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henchion, M.M.; McCarthy, M.; Resconi, V.C. Beef Quality Attributes: A Systematic Review of Consumer Perspectives. Meat Sci. 2017, 128, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Filho, L.; Pedro, M.A.M.; Telis-Romero, J.; Barboza, S.H.R. Influência da Temperatura e da Concentração do Cloreto de Sódio (NaCl) nas Isotermas de Sorção da Carne de Tambaqui (Colossoma macroparum). Ciênc. Tecnol. Aliment. 2006, 26, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho Júnior, B.C. Estudo da Evolução das Carnes Bovinas Salgadas no Brasil e Desenvolvimento de um Produto de Conveniência Similar à Carne-de-Sol. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y.; Chen, G.; Wang, D.; Hu, R.; Li, H.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Q.; Ming, J.; Chi, Y. Effects of Dry-Salting and Brine-Pickling Processes on the Physicochemical Properties, Nonvolatile Flavour Profiles and Bacterial Community during the Fermentation of Chinese Salted Radishes. LWT 2022, 157, 113084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, J.M.A.; Higuchi, L.H.; Feiden, A.; Maluf, M.L.F.; Dallagnol, J.M.; Boscolo, W.R. Salga Seca e Úmida de Filés de Pacu (Piaractus mesopotamicus). Ciênc. Agrár. 2011, 32, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Alves, L.L.; Delbem, A.C.B.; Abreu, U.G.P.; Lara, J.A.F. Avaliação Físico-Química e Microbiológica da Carne Soleada do Pantanal. Ciênc. Tecnol. Aliment. 2010, 30, 729–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mársico, E.T.; Moraes, I.A.; Silva, C.; Barreira, V.B.; Mantilla, S.P.S. Parâmetros Físico-Químicos de Qualidade de Peixe Salgado e Seco (Bacalhau) Comercializado em Mercados Varejistas. Rev. Inst. Adolfo Lutz 2009, 68, 406–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadini, C.; Nicoletti, V.; Meirelles, A.; Pessôa Filho, P. Operações Unitárias na Indústria de Alimentos; Blucher: São Paulo, Brazil, 2015; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283348857 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Miller, V.; Reedy, J.; Cudhea, F.; Zhang, J.; Shi, P.; Erndt-Marino, J.; Coates, J.; Micha, R.; Webb, P.; Mozaffarian, D.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Consumption of Animal-Source Foods between 1990 and 2018: Findings from the Global Dietary Database. Lancet Planet. Health 2022, 6, e243–e256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, P.A.; Lima, F.K.S.; Mendes, L.G.; Monte, A.L. Revisão Sistemática de Carne Salgada e seus Processos de Qualidade. Res. Soc. Dev. 2021, 10, e22389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mill, J.G.; Malta, D.C.; Machado, Í.E.; Pate, A.; Pereira, C.A.; Jaime, P.C.; Szwarcwald, C.L.; Rosenfeld, L.G. Estimation of Salt Intake by the Brazilian Population: Results from the 2013 National Health Survey. Rev. Bras. Epidemiol. 2019, 22 (Suppl. S2), e190009.SUPL.2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mill, J.G.; Malta, D.C.; Nilson, E.A.F.; Machado, I.E.; Jaime, P.C.; Bernal, R.T.I.; Cardoso, L.S.M.; Szwarcwald, C.L. Factors Associated with Salt Intake in the Brazilian Adult Population: National Health Survey. Ciênc. Saúde Colet. 2021, 26, 555–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, I.M.; Araújo, A.; Roediger, M.A.; Trevisan, D.M.; Andrade, Z.F.B. Factors Associated with Undiagnosed Hypertension among Elderly Adults in Brazil—ELSI-Brazil. Ciênc. Saúde Colet. 2022, 27, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Qi, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.Y.; Li, H.J.; Liu, H.H.; Zhang, X.T.; Du, J.; Liu, J. Dietary Factors Associated with Hypertension. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2011, 8, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, F.J.; MacGregor, G.A. Reducing Population Salt Intake Worldwide: From Evidence to Implementation. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2010, 52, 363–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guedes, L.F.; Felisbino-Mendes, M.S.; Vegi, A.S.; Meireles, A.L.; Menezes, M.C.; Malta, D.C.; Machado, Í.E. Health impacts caused by excessive sodium consumption in Brazil. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2022, 55, e0266-2021. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9022945/ (accessed on 22 October 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilson, E.A.F.; Andrade, G.C.; Claro, R.M.; Louzada, M.L.; Levy, R.B. Sodium intake according to NOVA food classification in Brazil. Cad. Saúde Pública 2024, 40, e00073823. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10896487/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Correia, R.T.P.; Biscontini, T.M.B. Influência da Dessalga e Cozimento sobre a Composição Química e Perfil de Ácidos Graxos de Charque e Jerked Beef. Ciênc. Tecnol. Aliment. 2003, 23, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheard, P.R.; Nute, G.; Chappell, A. The Effect of Cooking on the Chemical Composition of Meat Products with Special Reference to Fat Loss. Meat Sci. 1998, 49, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Estrada, M.T.; Penazzi, G.; Caboni, M.F.; Bertazzo, G.; Lercker, G. Effect of Different Cooking Methods on Some Lipids and Protein Components of Hamburgers. Meat Sci. 1997, 45, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil. Centro de Vigilância Sanitária. Portaria CVS nº 6, de 10 de março de 1999. Available online: https://midiasstoragesec.blob.core.windows.net/001/2017/03/portaria-seis.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Feitosa, T. Contaminação, Conservação e Alteração da Carne; Embrapa-CNPAT: Fortaleza, Brazil, 1999; Documentos, 34; Available online: https://www.infoteca.cnptia.embrapa.br/bitstream/doc/421977/1/Dc034.pdf (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Borch, E.; Arinder, P. Bacteriological Safety Issues in Red Meat and Ready-to-Eat Meat Products, as Well as Control Measures. Meat Sci. 2002, 62, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, H.; Gonçalves, A.; Nunes, M.L.; Vaz-Pires, P.; Costa, R. Quality changes during cod (Gadus morhua) desalting at different temperatures. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2015, 95, 2632–2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenzo, J.M.; Munekata, P.E.; Domínguez-Valencia, R.; Pateiro, M.; Saraiva, J.A.; Franco, D.J. Main Groups of Microorganisms of Relevance for Food Safety and Stability: General Aspects and Overall Description. In Innovative Technologies for Food Preservation; Barba, F.J., Sant’ana, A.S., Orlien, V., Koubaa, M., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 53–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC International. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International, 18th ed.; AOAC International: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2005; Method 925.10. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC International. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International, 16th ed.; AOAC International: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 1998; Method 900.02; Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/447361723/AOAC-Official-Method-900-02-Ash-of-Sugars-and-Syrups-pdf (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- AACC International. AACC International Approved Methods; AACC International: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2015; Available online: http://methods.aaccnet.org/toc.aspx (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- AOCS. Approved Procedure Am 5-04 Rapid Determination of Oil/Fat Utilizing High Temperature Solvent Extraction; American Oil Chemists’ Society: Urbana, IL, USA, 2005; Available online: http://www.academia.edu/30938058/AOCS (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Madsen, H.L.; Sorensen, B.; Skibsted, L.H.; Bertelsen, G. The Antioxidative Activity of Summer Savory (Satureja hortensis L.) and Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) in Dressing Stored Exposed to Light or in Darkness. Food Chem. 1998, 63, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC International. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International, 16th ed.; AOAC International: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 1997; Method 981.12; Method 942.15. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, A.C.B. Método de Dessalga de Jerked Beef como Procedimento para Garantir Inocuidade. Master’s Thesis, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 2013. Available online: https://repositorio.ufmg.br/handle/1843/BUBD-9EBPHR (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Silva, M.G.F. Controle de Segurança Microbiológica em Alimentos durante Descongelação e Dessalga. Master’s Thesis, Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Porto, Portugal, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sampaio, A.N.C.E.; Caron, E.F.F.; Cézar, C.K.C.; Raghiante, F.; Possebon, F.S.; Pereira, J.G.; Martins, O.A. Understanding Lipid Oxidation in Dried Meat and Cured Dried Meat: Insights from Peroxide Index Analysis. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 44, e00340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coró, F.A.G.; Gaino, V.O.; Carneiro, J.; Coelho, A.R.; Pedrão, M.R. Control of Lipid Oxidation in Jerked Beef through the Replacement of Sodium Nitrite by Natural Extracts of Yerba Mate and Propolis as Antioxidant Agent. Braz. J. Dev. 2020, 6, 4834–4850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.J.; Tan, M.; Ma, Y.; MacGregor, G.A. Salt reduction to prevent hypertension and cardiovascular disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 75, 632–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento. Instrução Normativa n°92, de 18 de Setembro de 2020; Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento: Brasília, Brazil, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Özisik, M.N. Transferência de Massa. In Transferência de Calor: Um Texto Básico; Guanabara: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1985; p. 597. [Google Scholar]

- Cremasco, M.A. Difusão Mássica; Blucher: São Paulo, Brazil, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Moraes, F.; Rodrigues, N.S.S. Maximização do Rendimento no Processamento de Carne Bovina (Músculo Semitendinosus) pelo Sistema Sous Vide. Braz. J. Food Technol. 2017, 20, e2016048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mediani, A.; Hamezah, H.S.; Jam, F.A.; Mahadi, N.F.; Chan, S.X.Y.; Rohani, E.R.; Che Lah, N.H.; Azlan, U.K.; Khairul Annuar, N.A.; Azman, N.A.F.; et al. A Comprehensive Review of Drying Meat Products and the Associated Effects and Changes. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1057366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estevez, M. Protein carbonyls in meat systems: A review. Meat Sci. 2011, 89, 259–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, R.; Pateiro, M.; Gagaoua, M.; Barba, F.J.; Zhang, W.; Lorenzo, J.M. A Comprehensive Review on Lipid Oxidation in Meat and Meat Products. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wazir, H.; Chay, S.Y.; Ibadullah, W.Z.W.; Zarei, M.; Mustapha, N.A.; Saari, N. Lipid Oxidation and Protein Co-Oxidation in Ready-to-Eat Meat Products as Affected by Temperature, Antioxidant, and Packaging Material during 6 Months of Storage. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 38565–38577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, X.; Zhou, G.; Xu, X. Heat-Induced Protein and Lipid Oxidation in Meat Products: Implications for Quality and Safety. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 24315–24328. [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu, H.; Shimizu, T. Problems of Lipid Oxidation in Minced Meat Products for a Long Shelf Life. Meat Sci. 2022, 183, 108675. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.S.; Al-Khusaibi, M.; Guizani, N. Lipid Oxidation and Its Impact on the Quality of Meat and Meat Products. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2015, 14, 421–436. [Google Scholar]

- Shakil, M.H.; Trisha, A.T.; Rahman, M.; Talukdar, S.; Kobun, R.; Huda, N.; Zzaman, W. Nitrites in Cured Meats, Health Risk Issues, Alternatives to Nitrites: A Review. Foods 2023, 12, 1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, A.B.; Silva, M.V.; Lannes, S.C.S. Lipid Oxidation in Meat: Mechanisms and Protective Factors—A Review. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 38, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Control | Room Temperature | Refrigerated | Heat | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD (mg de Na/100 g) | % Reduction | Mean ± SD (mg de Na/100 g) | % Reduction | Mean ± SD (mg de Na/100 g) | % Reduction | ||

| Brand A | 6339.2 ± 317.2 cA | 1527.4 ± 154.2 a | 75.9 | 1643.0 ± 293.5 a | 74.1 | 2676.3 ± 400.9 b | 57.8 |

| Brand B | 6538.6 ± 415.6 dA | 1565.8 ± 190.3 a | 76.1 | 1946.8 ± 273.6 b | 70.2 | 3148.7 ± 454.2 c | 51.8 |

| Brand C | 6459.8 ± 465.7 dA | 1653.6 ± 162.9 a | 74.4 | 2122.4 ± 267.8 b | 67.1 | 2922.8 ± 385.1 c | 54.8 |

| Control | Room Temp. | Refrigerated | Heat | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brand A | ||||

| Moisture | 54.12 ± 1.24 Aa | 73.82 ± 1.57 b | 73.34 ± 1.70 b | 54.48 ± 2.23 a |

| Ashes | 16.98 ± 0.73 Ad | 3.95 ± 0.49 a | 4.36 ± 0.81 b | 7.22 ± 0.88 c |

| Carbohydrate | 1.64 ± 0.84 Ab | 0.56 ± 0.54 ab | 0.10 ± 0.06 a | 2.69 ± 0.69 c |

| Protein | 23.50 ± 1.39 Ab | 18.70 ± 2.11 a | 18.07 ± 1.40 a | 31.29 ± 2.82 c |

| Lipids | 3.70 ± 0.98 Aa | 3.00 ± 0.62 b | 3.94 ± 0.90 ac | 4.19 ± 1.51 c |

| Brand B | ||||

| Moisture | 56.44 ± 2.57 Aa | 75.21 ± 2.05 c | 73.80 ± 2.38 d | 54.42 ± 2.52 b |

| Ashes | 17.15 ± 0.68 Ad | 3.87 ± 0.28 a | 4.92 ± 0.47 b | 8.76 ± 0.78 c |

| Carbohydrate | 0.47 ± 0.34 Aa | 0.55 ± 0.37 a | 2.14 ± 0.97 b | 0.35 ± 0.09 a |

| Protein | 23.99 ± 3.22 Ab | 18.08 ± 1.95 a | 17.69 ± 2.86 a | 33.49 ± 3.09 c |

| Lipids | 1.97 ± 0.73 Bb | 2.40 ± 0.71 c | 1.62 ± 0.53 a | 3.46 ± 0.77 d |

| Brand C | ||||

| Moisture | 56.07 ± 0.67 Ab | 75.38 ± 2.37 c | 74.83 ± 1.84 c | 54.26 ± 1.23 a |

| Ashes | 18.73 ± 0.43 Bd | 4.74 ± 0.59 a | 6.00 ± 0.53 b | 8.05 ± 0.77 c |

| Carbohydrate | 0.31 ± 0.48 Aa | 0.88 ± 0.80 a | 1.30 ± 0.30 a | 1.62 ± 0.78 a |

| Protein | 22.23 ± 1.27 Bb | 16.92 ± 1.14 a | 16.38 ± 1.13 a | 33.34 ± 1.26 c |

| Lipids | 2.85 ± 1.32 Cb | 1.37 ± 0.94 a | 1.48 ± 0.68 a | 2.71 ± 0.57 b |

| Control | Room Temperature | Refrigerated | Heat | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brand A | ||||

| Acidity (g/100 g) | 8.82 ± 1.29 d | 3.83 ± 1.36 a | 4.78 ± 1.20 b | 5.54 ± 1.37 c |

| pH | 5.83 ± 0.20 a | 6.01 ± 0.27 b | 6.03 ± 0.39 b | 5.82 ± 0.23 a |

| Brand B | ||||

| Acidity (g/100 g) | 11.79 ± 1.85 d | 6.47 ± 1.48 a | 6.94 ± 1.09 b | 9.75 ± 0.87 c |

| pH | 5.61 ± 0.20 a | 5.64 ± 0.17 a | 5.63 ± 0.19 a | 5.76 ± 0.10 b |

| Brand C | ||||

| Acidity (g/100 g) | 10.94 ± 0.99 c | 5.67 ± 0.69 a | 5.53 ± 0.49 a | 8.28 ± 2.57 b |

| pH | 5.89 ± 0.11 a | 5.76 ± 0.05 b | 5.82 ± 0.04 c | 5.86 ± 0.05 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ibiapina, M.d.D.P.F.; Corino de Melo, M.E.; Mendonça, M.A.; Lopes da Silva, F.; Tonhá, M.d.S.; Botelho, R.B.A. Jerked Beef: Chemical Composition and Desalting Techniques. Foods 2025, 14, 3745. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14213745

Ibiapina MdDPF, Corino de Melo ME, Mendonça MA, Lopes da Silva F, Tonhá MdS, Botelho RBA. Jerked Beef: Chemical Composition and Desalting Techniques. Foods. 2025; 14(21):3745. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14213745

Chicago/Turabian StyleIbiapina, Maria do Desterro Pereira Ferreira, Maria Eduarda Corino de Melo, Márcio Antônio Mendonça, Frederico Lopes da Silva, Myller de Sousa Tonhá, and Raquel Braz Assunção Botelho. 2025. "Jerked Beef: Chemical Composition and Desalting Techniques" Foods 14, no. 21: 3745. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14213745

APA StyleIbiapina, M. d. D. P. F., Corino de Melo, M. E., Mendonça, M. A., Lopes da Silva, F., Tonhá, M. d. S., & Botelho, R. B. A. (2025). Jerked Beef: Chemical Composition and Desalting Techniques. Foods, 14(21), 3745. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14213745