Structural Engineering of Tyrosine-Based Neuroprotective Peptides: A New Strategy for Efficient Blood–Brain Barrier Penetration

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

2.2. Molecular Docking

2.3. NMR Measurements

2.4. FTIR Spectroscopy

2.5. CD Measurements

2.6. Antioxidant Activity of EV, TW, and YV Peptides

2.6.1. Determination of DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity

2.6.2. Determination of ABTS Radical Scavenging Activity

2.6.3. Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity (ORAC) Assay

2.7. Cell Culture and Treatment

2.8. Transwell

2.9. Real-Time Ex Vivo Imaging of Rhodamine B-EV Peptide Injected into the Tail Vein

2.10. In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion

2.11. Plasma Half-Life

2.12. Brain Pharmacokinetics

2.13. RP-HPLC Analysis

2.14. Measurement of Cellular Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Levels

2.15. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Construction and Screening of BBB Penetrating Peptides

3.2. Secondary Structure

3.2.1. Structural Spectroscopic Analysis of the Peptides

3.2.2. CD

3.3. Antioxidant Activity

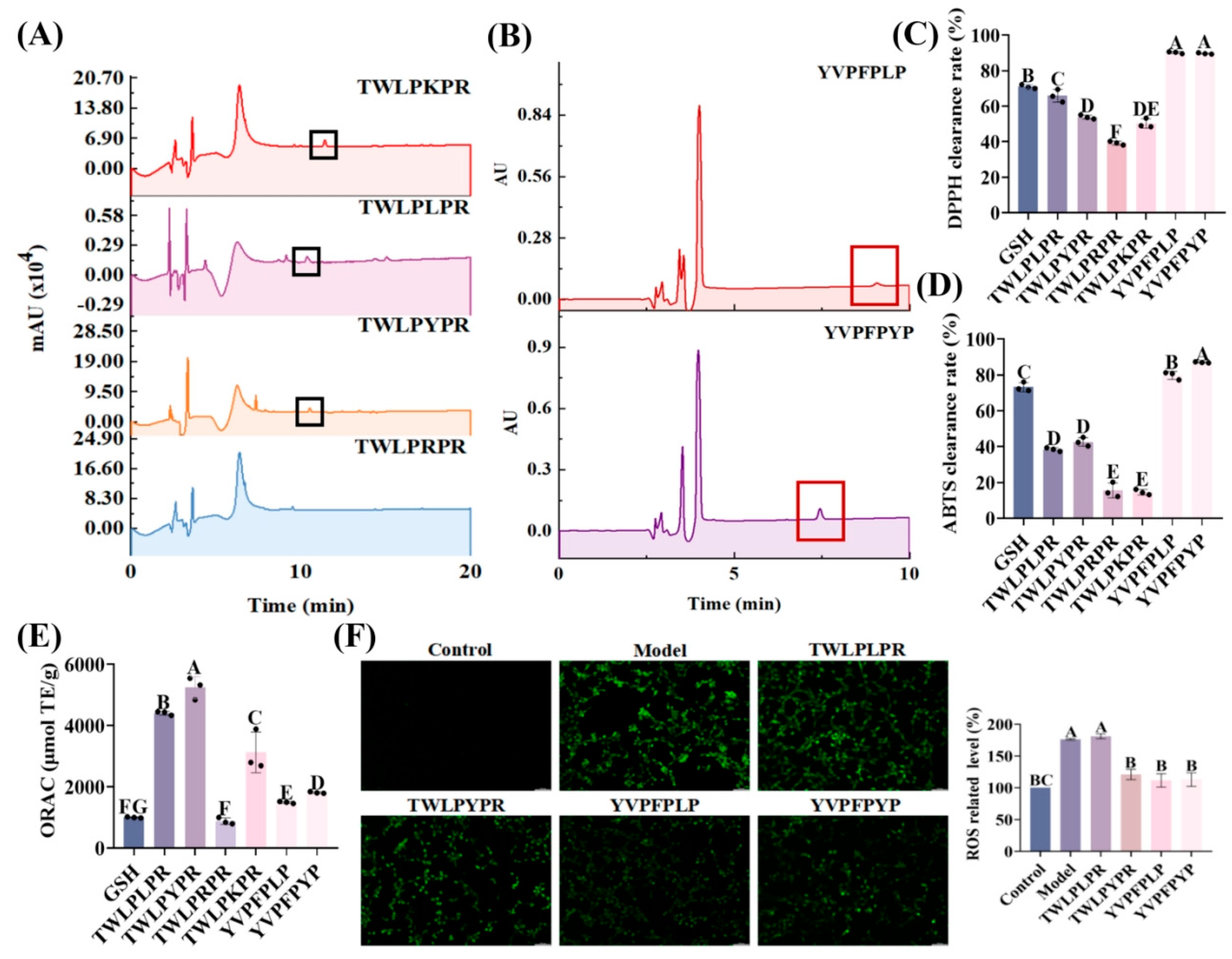

3.3.1. DPPH Radical Scavenging

3.3.2. ABTS Radical Scavenging

3.3.3. ORAC

3.4. In Vitro BBB Penetration Ability of EV Peptides

3.5. Evaluation of the Biostability and Neuroprotective Function of EV Peptides

3.5.1. In Vitro Simulation of Gastrointestinal Digestion of EV Peptides

3.5.2. Half-Life of Plasma

3.5.3. Neuroprotective Properties

3.6. In Vitro BBB Penetration Ability and Secondary Structure Validation of TWLPYPR and YVPFPYP

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Katayama, S.; Corpuz, H.M.; Nakamura, S. Potential of plant-derived peptides for the improvement of memory and cognitive function. Peptides 2021, 142, 170571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilsky, E.J.; Egleton, R.D.; Mitchell, S.A.; Palian, M.M.; Davis, P.; Huber, J.D.; Jones, H.; Yamamura, H.I.; Janders, J.; Davis, T.P.; et al. Enkephalin glycopeptide analogues produce analgesia with reduced dependence liability. J. Med. Chem. 2000, 43, 2586–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albensi, B.C. Tumor Necrosis Factor and Drug Delivery in the Blood-Brain Barrier. Drug News Perspect. 2002, 15, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulik, R.S.; Bing, C.; Ladouceur-Wodzak, M.; Munaweera, I.; Chopra, R.; Corbin, I.R. Localized delivery of low-density lipoprotein docosahexaenoic acid nanoparticles to the rat brain using focused ultrasound. Biomaterials 2016, 83, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiviniemi, V.; Korhonen, V.; Kortelainen, J.; Rytky, S.; Keinänen, T.; Tuovinen, T.; Isokangas, M.; Sonkajärvi, E.; Siniluoto, T.; Nikkinen, J.; et al. Real-time monitoring of human blood-brain barrier disruption. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, C.K.; Budinger, T.F. Evaluation of blood-brain-barrier permeability changes in rhesus-monkeys and man using rb-82 and positron emission tomography. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 1981, 5, 792–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, B.; Javed, A.; Kow, C.S.; Hasan, S.S. Pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment options for sleep disturbances in Alzheimer’s disease. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2023, 23, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.F.; Hao, Y.D.; Wang, T.Y.; Cai, P.L.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, K.J.; Lin, H.; Lv, H. Prediction of blood-brain barrier penetrating peptides based on data augmentation with Augur. BMC Biol. 2024, 22, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, A.H.; Lee, S.; Jeon, S.; Kim, G.T.; Lee, E.J.; Kim, D.; Kim, Y.; Park, T.S. Addition of an N-Terminal Poly-Glutamate Fusion Tag Improves Solubility and Production of Recombinant TAT-Cre Recombinase in Escherichia coli. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 30, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hervé, F.; Ghinea, N.; Scherrmann, J.M. CNS delivery via adsorptive transcytosis. AAPS J. 2008, 10, 455–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Tai, L.; Zhang, W.; Wei, G.; Pan, W.; Lu, W. Penetratin, a potentially powerful absorption enhancer for noninvasive intraocular drug delivery. Mol. Pharm. 2014, 11, 1218–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oba, M.; Nakajima, S.; Misao, K.; Yokoo, H.; Tanaka, M. Effect of helicity and hydrophobicity on cell-penetrating ability of arginine-rich peptides. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2023, 91, 117409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujals, S.; Giralt, E. Proline-rich, amphipathic cell-penetrating peptides. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2008, 60, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.; Park, J.; Chong, S.E.; Kim, S.; Choi, Y.; Nam, S.H.; Lee, Y. Effective cell penetration of negatively-charged proline-rich SAP(E) peptides with cysteine mutation. Pept. Sci. 2023, 115, e24301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frøslev, P.; Franzyk, H.; Ozgür, B.; Brodin, B.; Kristensen, M. Highly cationic cell-penetrating peptides affect the barrier integrity and facilitates mannitol permeation in a human stem cell-based blood-brain barrier model. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 168, 106054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Navarro, M.; Teixidó, M.; Giralt, E. Jumping Hurdles: Peptides Able To Overcome Biological Barriers. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 1847–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, H.S.; Lee, J.H.; Park, Y.S.; Kim, Y.O.; Park, J.; Yang, T.Y.; Jin, K.; Lee, J.; Park, S.; You, J.M.; et al. Tyrosine-mediated two-dimensional peptide assembly and its role as a bio-inspired catalytic scaffold. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredeloux, P.; Cavelier, F.; Dubuc, I.; Vivet, B.; Costentin, J.; Martinez, J. Synthesis and biological effects of c(Lys-Lys-Pro-Tyr-Ile-Leu-Lys-Lys-Pro-Tyr-Ile-Leu) (JMV2012), a new analogue of neurotensin that crosses the blood-brain barrier. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 1610–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khapchaev, A.Y.; Kazakova, O.A.; Samsonov, M.V.; Sidorova, M.V.; Bushuev, V.N.; Vilitkevich, E.L.; Az’muko, A.A.; Molokoedov, A.S.; Bespalova, Z.D.; Shirinsky, V.P. Design of peptidase-resistant peptide inhibitors of myosin light chain kinase. J. Pept. Sci. 2016, 22, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, D.; Zhao, F.; Liu, C.; Wang, J.; Guo, Y.; Liu, J.; Min, W. Antioxidant hydrolyzed peptides from Manchurian walnut (Juglans mandshurica Maxim.) attenuate scopolamine-induced memory impairment in mice. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 5142–5152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Bordoni, L.; Min, W.; Gabbianelli, R. Insights into the Hippocampus Proteomics Reveal Epigenetic Properties of Walnut-Derived Peptides in a Low-Grade Neuroinflammation Model. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2023, 71, 8252–8263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, H.; Li, J.; Xu, J.; Fang, L.; Liu, C.; Wu, D.; Min, W. Structure-activity relationship of walnut peptide in gastrointestinal digestion, absorption and antioxidant activity. Lwt 2023, 189, 115521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, F.; Qin, H.; Lu, H.; Fang, L.; Wang, J.; Min, W. Potential mechanisms mediating the protective effects of a peptide from walnut (Juglans mandshurica Maxim.) against hydrogen peroxide induced neurotoxicity in PC12 cells. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 3491–3501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Dang, Q.; Liu, C.; Liu, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhao, F.; Wang, Q.; Min, W. Caveolin Regulates the Transport Mechanism of the Walnut-Derived Peptide EVSGPGYSPN to Penetrate the Blood–Brain Barrier. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 19786–19799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, Q.; Wu, D.; Li, Y.; Fang, L.; Liu, C.; Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Min, W. Walnut-derived peptides ameliorate d-galactose-induced memory impairments in a mouse model via inhibition of MMP-9-mediated blood-brain barrier disruption. Food Res. Int. 2022, 162, 112029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, W.; Dang, Q.; Li, Z.; Zhao, X.; Shen, Y.; Fang, L.; Liu, C. Walnut-derived peptides cross the blood-brain barrier and ameliorate Abeta-induced hypersynchronous neural network activity. Food Res. Int. 2024, 197, 115302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Dang, Q.; Shen, Y.; Guo, L.; Liu, C.; Wu, D.; Fang, L.; Leng, Y.; Min, W. Therapeutic effects of a walnut-derived peptide on NLRP3 inflammasome activation, synaptic plasticity, and cognitive dysfunction in T2DM mice. Food Funct. 2024, 15, 2295–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Dang, Q.; Fang, L.; Wu, D.; Li, Y.; Zhao, F.; Liu, C.; Min, W. Walnut-Derived Peptides Ameliorate Scopolamine-Induced Memory Impairments in a Mouse Model via Activation of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor γ-Mediated Excitotoxicity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 12541–12554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, L.; Wang, L.; Zhang, T.; Yu, Z.; Liu, J. Hydrolysis and transepithelial transport of two corn gluten derived bioactive peptides in human Caco-2 cell monolayers. Food Res. Int. 2018, 106, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Fang, L.; Liu, C.; Wang, J.; Wu, D.; Zeng, Q.; Leng, Y.; Min, W. Effect of bi-enzyme hydrolysis on the properties and composition of hydrolysates of Manchurian walnut dreg protein. Food Chem. 2024, 447, 138947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yue, F.; Lu, Y.; Qiu, H.; Gao, D.; Gao, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Z.; et al. In vitro kinetic evaluation of the free radical scavenging ability of propofol. Anesthesiology 2012, 116, 1258–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, M.; Kageruka, H.; Collin, S. Use of Botanical Ingredients: Nice Opportunities to Avoid Premature Oxidation of NABLABs by Increasing Their ORAC Values Strongly Impacted by Dealcoholization or Pasteurization. Molecules 2024, 29, 2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Xie, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, S.; Yang, J.; Wang, R.; Sun, Y.; Wang, X.; Xu, J.; Chen, D.; et al. The influx/efflux mechanisms of d-peptide ligand of nAChRs across the blood–brain barrier and its therapeutic value in treating glioma. J. Control. Release 2020, 327, 384–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markov, A.G.; Bikmurzina, A.E.; Fedorova, A.A.; Krivoi, I.I. Krivoi Methyl-beta-Cyclodextrin Alters the Level of Tight Junction Proteins in the Rat Cerebrovascular Endothelium. J. Evol. Biochem. Physiol. 2022, 58, 849–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Kabanov, A.V. Brain delivery of proteins via their fatty acid and block copolymer modifications. J. Drug Target. 2013, 21, 940–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyo, S.; Grigorian, A.; Cohen-Addad, D.; Kolla, S. RadRemind!–An Automated Paging System for Reminding Radiology Residents of Their Roles and Responsibilities. J. Digit. Imaging 2021, 34, 489–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeung, T.; Gilbert, G.E.; Shi, J.; Silvius, J.; Kapus, A.; Grinstein, S. Membrane phosphatidylserine regulates surface charge and protein localization. Science 2008, 319, 210–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, A.; Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Kawai, M. Free radical scavenging by brain homogenate: Implication to free radical damage and antioxidant defense in brain. Neurochem. Int. 1994, 24, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, L.; Zhao, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Yu, L.; Zeng, X.; Yang, J.; Tian, M.; Liu, H.; Yang, B. Identification of a flavonoid C-glycoside as potent antioxidant. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2017, 110, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arise, A.K.; Alashi, A.M.; Nwachukwu, I.D.; Ijabadeniyi, O.A.; Aluko, R.E.; Amonsou, E.O. Antioxidant activities of bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea) protein hydrolysates and their membrane ultrafiltration fractions. Food Funct. 2016, 7, 2431–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imperiali, B.; Shannon, K.L. Differences between Asn-Xaa-Thr-containing peptides: A comparison of solution conformation and substrate behavior with oligosaccharyltransferase. Biochemistry 1991, 30, 4374–4380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, W.; Tang, L.; Wang, B.; Chen, J.; Su, W.; Osako, K.; Tanaka, M. Antioxidant properties of fractions isolated from blue shark (Prionace glauca) skin gelatin hydrolysates. J. Funct. Foods 2014, 11, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhang, D.; Liu, M.; Li, Y.; Lv, R.; Li, X.; Wang, Q.; Ren, D.; Wu, L.; Zhou, H. Identification of Antioxidant Peptides Derived from Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) Skin and Their Mechanism of Action by Molecular Docking. Foods 2022, 11, 2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Feng, M.Q.; Sun, J.; Xu, X.L.; Zhou, G.H. Protein degradation and peptide formation with antioxidant activity in pork protein extracts inoculated with Lactobacillus plantarum and Staphylococcus simulans. Meat Sci. 2020, 160, 107958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wu, G.; Yang, J.; He, C.; Xiong, H.; Ma, Y. Abalone visceral peptides containing Cys and Tyr exhibit strong in vitro antioxidant activity and cytoprotective effects against oxidative damage. Food Chem. X 2023, 17, 100582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.-Y.; Mi, C.-X.; Chen, J.; Jiao, R.-W.; Li, X.; Wang, Q.-K.; He, Y.-H.; Ren, D.-D.; Wu, L.; Zhou, H. Contribution of amino acid composition and secondary structure to the antioxidant properties of tilapia skin peptides. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2023, 18, 1483–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohashi, Y.; Onuma, R.; Naganuma, T.; Ogawa, T.; Naude, R.; Nokihara, K.; Muramoto, K. Antioxidant Properties of Tripeptides Revealed by a Comparison of Six Different Assays. Food Sci. Technol. Res. 2015, 21, 695–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prior, R.L.; Wu, X.; Schaich, K. Standardized methods for the determination of antioxidant capacity and phenolics in foods and dietary supplements. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 4290–4302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Z.M.; Li, X.M.; Li, F.; Wu, J.J.; Kong, L.Y.; Wang, X.B. Synthesis and evaluation of multi-target-directed ligands for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease based on the fusion of donepezil and melatonin. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2016, 24, 4324–4338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Cai, P.; Liu, Q.; Wu, J.; Yin, Y.; Wang, X.; Kong, L. Novel 8-hydroxyquinoline derivatives targeting β-amyloid aggregation, metal chelation and oxidative stress against Alzheimer’s disease. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2018, 26, 3191–3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, C.Y.; Kim, H.S.; Cha, K.H.; Won, D.H.; Lee, J.Y.; Jang, S.W.; Sohn, U.D. The Effects of Donepezil, an Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitor, on Impaired Learning and Memory in Rodents. Biomol. Ther. 2018, 26, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirhaghi, M.; Mamashli, F.; Moosavi-Movahedi, F.; Arghavani, P.; Amiri, A.; Davaeil, B.; Mohammad-Zaheri, M.; Mousavi-Jarrahi, Z.; Sharma, D.; Langel, Ü.; et al. Cell-Penetrating Peptides: Promising Therapeutics and Drug-Delivery Systems for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Mol. Pharm. 2024, 21, 2097–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.D.; Zou, M.J.; Zhang, Y.T.; Fu, W.L.; Xu, T.; Wang, J.X.; Xia, W.R.; Huang, Z.G.; Gan, X.D.; Zhu, X.M.; et al. A novel IL-1RA-PEP fusion protein with enhanced brain penetration ameliorates cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury by inhibition of oxidative stress and neuroinflammation. Exp. Neurol. 2017, 297, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Chen, H.; Ding, L.; Gong, J.; Zhang, M.; Guo, W.; Xu, P.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y. Trojan Horse Delivery of 4,4′-Dimethoxychalcone for Parkinsonian Neuroprotection. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2004555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oka, J.I. Improving Effects of Peptides on Brain Malfunction and Intranasal Delivery of Those Derivatives to the Brain. Yakugaku Zasshi 2019, 139, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackman, J.A.; Costa, V.V.; Park, S.; Real, A.L.C.V.; Park, J.H.; Cardozo, P.L.; Ferhan, A.R.; Olmo, I.G.; Moreira, T.P.; Bambirra, J.L.; et al. Therapeutic treatment of Zika virus infection using a brain-penetrating antiviral peptide. Nat. Mater. 2018, 17, 971–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muolokwu, C.E.; Chaulagain, B.; Gothwal, A.; Mahanta, A.K.; Tagoe, B.; Lamsal, B.; Singh, J. Functionalized nanoparticles to deliver nucleic acids to the brain for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1405423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaev, N.K.; Stelmashook, E.V.; Genrikhs, E.E. Role of Nerve Growth Factor in Plasticity of Forebrain Cholinergic Neurons. Biochemistry 2017, 82, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makani, V.; Jang, Y.G.; Christopher, K.; Judy, W.; Eckstein, J.; Hensley, K.; Chiaia, N.; Kim, D.S.; Park, J. BBB-Permeable, Neuroprotective, and Neurotrophic Polysaccharide, Midi-GAGR. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, M.; Zhang, L.; Chen, P. Membrane Internalization Mechanisms and Design Strategies of Arginine-Rich Cell-Penetrating Peptides. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futaki, S.; Nakase, I. Cell-Surface Interactions on Arginine-Rich Cell-Penetrating Peptides Allow for Multiplex Modes of Internalization. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 2449–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Yin, L.; Lu, H.; Cheng, J. Water-soluble poly(L-serine)s with elongated and charged side-chains: Synthesis, conformations, and cell-penetrating properties. Biomacromolecules 2012, 13, 2609–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Lin, X.; Long, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Mi, H.; Yan, H. A peptide fragment derived from the T-cell antigen receptor protein alpha-chain adopts beta-sheet structure and shows potent antimicrobial activity. Peptides 2009, 30, 647–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, T.T.; Koh, J.A.; Wong, C.C.; Sabri, M.Z.; Wong, F.C. Computational Screening for the Anticancer Potential of Seed-Derived Antioxidant Peptides: A Cheminformatic Approach. Molecules 2021, 26, 7396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Courelli, V.; Ahmad, A.; Ghassemian, M.; Pruitt, C.; Mills, P.J.; Schmid-Schönbein, G.W. Digestive Enzyme Activity and Protein Degradation in Plasma of Heart Failure Patients. Cell. Mol. Bioeng. 2021, 14, 583–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binder, U.; Skerra, A. PASylated Thymosin α1: A Long-Acting Immunostimulatory Peptide for Applications in Oncology and Virology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 22, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Z.; Sahu, B.S.; He, R.; Finan, B.; Cero, C.; Verardi, R.; Razzoli, M.; Veglia, G.; Di Marchi, R.D.; Miles, J.M.; et al. Clearance kinetics of the VGF-derived neuropeptide TLQP-21. Neuropeptides 2018, 71, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindqvist, A.; Rip, J.; Gaillard, P.J.; Björkman, S.; Hammarlund-Udenaes, M. Enhanced brain delivery of the opioid peptide DAMGO in glutathione pegylated liposomes: A microdialysis study. Mol. Pharm. 2013, 10, 1533–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Huang, J. Optimization of Protein and Peptide Drugs Based on the Mechanisms of Kidney Clearance. Protein Pept. Lett. 2018, 25, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Mubarak, M.A.; Leontari, I.; Danika, C.; Katsila, T.; Sivolapenko, G. Development and validation of a UHPLC-UV method for the determination of a prostate secretory protein 94-derived synthetic peptide (PCK3145) in human plasma and assessment of its stability in human plasma. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2016, 30, 1476–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sequence | Binding Energy (kcal/mol) | Ki (Kd) (298 K, nM) | PI | GRAVY | Solubility | Number of Net Charges at pH = 7.0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EVSGPGYSPN | −18.3 | 2,380,115.19 | 9.36 | −0.93 | Hydrophobic | 0.98 |

| EVSGPGKSPN | −17.7 | 153,583.29 | 9.71 | −1.23 | Hydrophilic | 0.98 |

| EVSGPGRSPN | −17.4 | 223,109.42 | 10.56 | −1.29 | Hydrophilic | 0.98 |

| EVSGPGFSPN | −17.3 | 18,455.9 | 6.36 | −0.56 | Hydrophobic | −0.02 |

| EVSGPGSSPN | −17.3 | 17,249.74 | 6.36 | −0.92 | Hydrophilic | −0.02 |

| EVSGPGTSPN | −17.3 | 220,858.95 | 6.36 | −0.91 | Hydrophilic | −0.02 |

| EVSGPGASPN | −17.2 | 56,866.77 | 6.36 | −0.66 | Hydrophilic | −0.02 |

| EVSGPGWSPN | −17.1 | 62,194.35 | 6.36 | −0.93 | Hydrophobic | −0.02 |

| EVSGPGDSPN | −16.9 | 25,356.733 | 4 | −1.19 | Hydrophilic | −1.02 |

| EVSGPGVSPN | −16.9 | 21,450.88 | 6.36 | −0.42 | Hydrophilic | −0.02 |

| EVSGPGMSPN | −16.7 | 11,211.37 | 6.36 | −0.65 | Hydrophilic | −0.02 |

| EVSGPGNSPN | −16.4 | 92,825.22 | 6.36 | −1.19 | Hydrophilic | −0.02 |

| EVSGPGGSPN | −16.4 | 10,857.16 | 6.36 | −0.88 | Hydrophilic | −0.02 |

| EVSGPGHSPN | −16.4 | 98,813.73 | 7.56 | −1.16 | Hydrophilic | 0.21 |

| EVSGPGISPN | −16.3 | 66,543.2 | 6.36 | −0.39 | Hydrophilic | −0.02 |

| EVSGPGCSPN | −16.2 | 10,147.6 | 8.56 | −0.59 | Hydrophilic | 0.94 |

| EVSGPGQSPN | −16.2 | 55,725.34 | 6.36 | −1.19 | Hydrophilic | −0.02 |

| EVSGPGLSPN | −16.2 | 5058.6 | 6.36 | −0.46 | Hydrophilic | −0.02 |

| EVSGPGESPN | −15.9 | 25,571.86 | 4.1 | −1.19 | Hydrophilic | −1.02 |

| EVSGPGPSPN | −15.4 | 25,701.81 | 6.36 | −1 | Hydrophilic | −0.02 |

| Sequence | Papp (cm/s) | Brain Accumulation Concentration (cm/s) |

|---|---|---|

| EVSGPGLSPN | 3.78 ± 0.40 × 10−6 | 0.25 ± 0.11 µg/g |

| EVSGPGYSPN | 8.10 ± 0.34 × 10−6 | 1.25 ± 0.91 µg/g |

| EVSGPGKSPN | 1.36 ± 0.15 × 10−6 | |

| EVSGPGRSPN | - | |

| TWLPLPR | 6.85 ± 0.51 × 10−6 | |

| TWLPYPR | 7.06 ± 0.51 × 10−6 | |

| TWLPKPR | 3.45 ± 0.40 × 10−6 | |

| TWLPRPR | - | |

| YVPFPLP | 9.99 ± 0.05 × 10−7 | |

| YVPFPYP | 3.62 ± 0.47 × 10−6 |

| Time | EVSGPGLSPN | EVSGPGYSPN |

|---|---|---|

| 0 h | 100% | 100% |

| 1 h | 99.75 ± 0.35% | 96.64 ± 0.53% |

| 2 h | 99.00 ± 0.75% | 92.42 ± 0.74% |

| 4 h | 98.13 ± 0.06% | 80.50 ± 0.65% |

| 8 h | 97.86 ± 0.49% | 58.64 ± 0.52% |

| 12 h | 96.86 ± 0.50% | 50.96 ± 0.64% |

| 24 h | 95.62 ± 0.64% | 24.29 ± 1.94% |

| 36 h | 94.96 ± 0.36% | 0% |

| 48 h | 94.77 ± 0.64% | 0% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Z.; Zhu, Q.; Qiao, Y.; Fu, J.; Tao, L.; Min, W. Structural Engineering of Tyrosine-Based Neuroprotective Peptides: A New Strategy for Efficient Blood–Brain Barrier Penetration. Foods 2025, 14, 3744. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14213744

Li Z, Zhu Q, Qiao Y, Fu J, Tao L, Min W. Structural Engineering of Tyrosine-Based Neuroprotective Peptides: A New Strategy for Efficient Blood–Brain Barrier Penetration. Foods. 2025; 14(21):3744. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14213744

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Zehui, Qiyue Zhu, Yashu Qiao, Junxi Fu, Li Tao, and Weihong Min. 2025. "Structural Engineering of Tyrosine-Based Neuroprotective Peptides: A New Strategy for Efficient Blood–Brain Barrier Penetration" Foods 14, no. 21: 3744. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14213744

APA StyleLi, Z., Zhu, Q., Qiao, Y., Fu, J., Tao, L., & Min, W. (2025). Structural Engineering of Tyrosine-Based Neuroprotective Peptides: A New Strategy for Efficient Blood–Brain Barrier Penetration. Foods, 14(21), 3744. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14213744