Encapsulation of Fish Oil in Pullulan/Sodium Caseinate Nanofibers: Fabrication, Characterization, and Oxidative Stability

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Fish Oil Composition

2.2. Electrospinning Solutions Preparation

2.3. Electrical Conductivity, Surface Tension, and pH

2.4. Droplet Size

2.5. Viscosity

2.6. Encapsulation Efficiency and Loading Capacity

2.7. Electrospinning

2.8. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.9. Water Contact Angle

2.10. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR)

2.11. Diffraction of X-Rays (XRD)

2.12. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

2.13. Bioactive Properties

2.14. Antidiabetic Activity

2.15. Oxidative Stability (Peroxide Values)

2.16. Molecular Docking and Density Functional Theory (DFT)-Based Simulation Procedures

2.16.1. Molecular Identification and Optimization

2.16.2. Molecular Docking and Post-Molecular Docking Analysis

2.16.3. DFT Simulation Analysis

2.17. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Emulsion Characterizations

3.1.1. Electrical Conductivity, Surface Tension, and pH

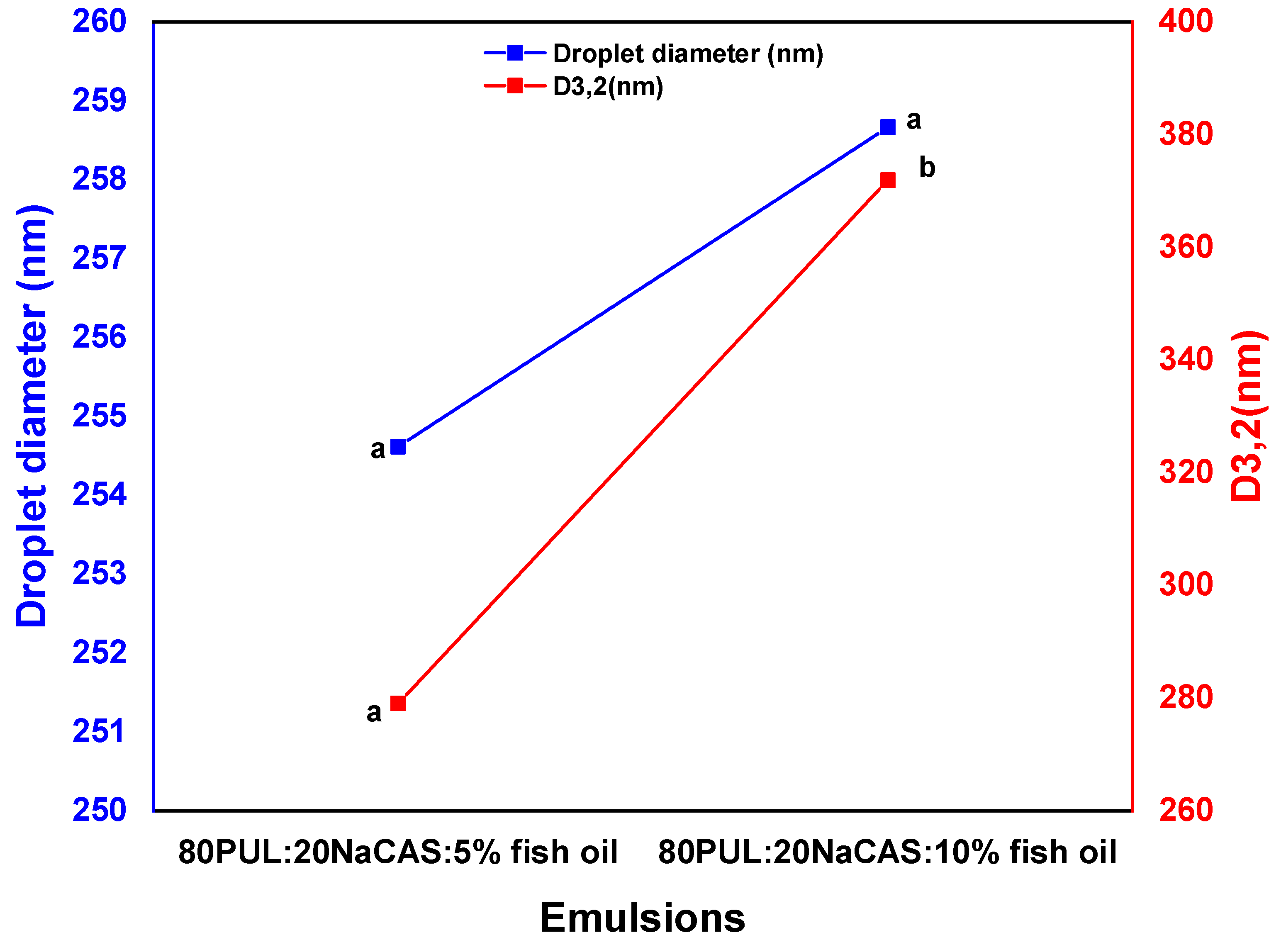

3.1.2. Droplet Size

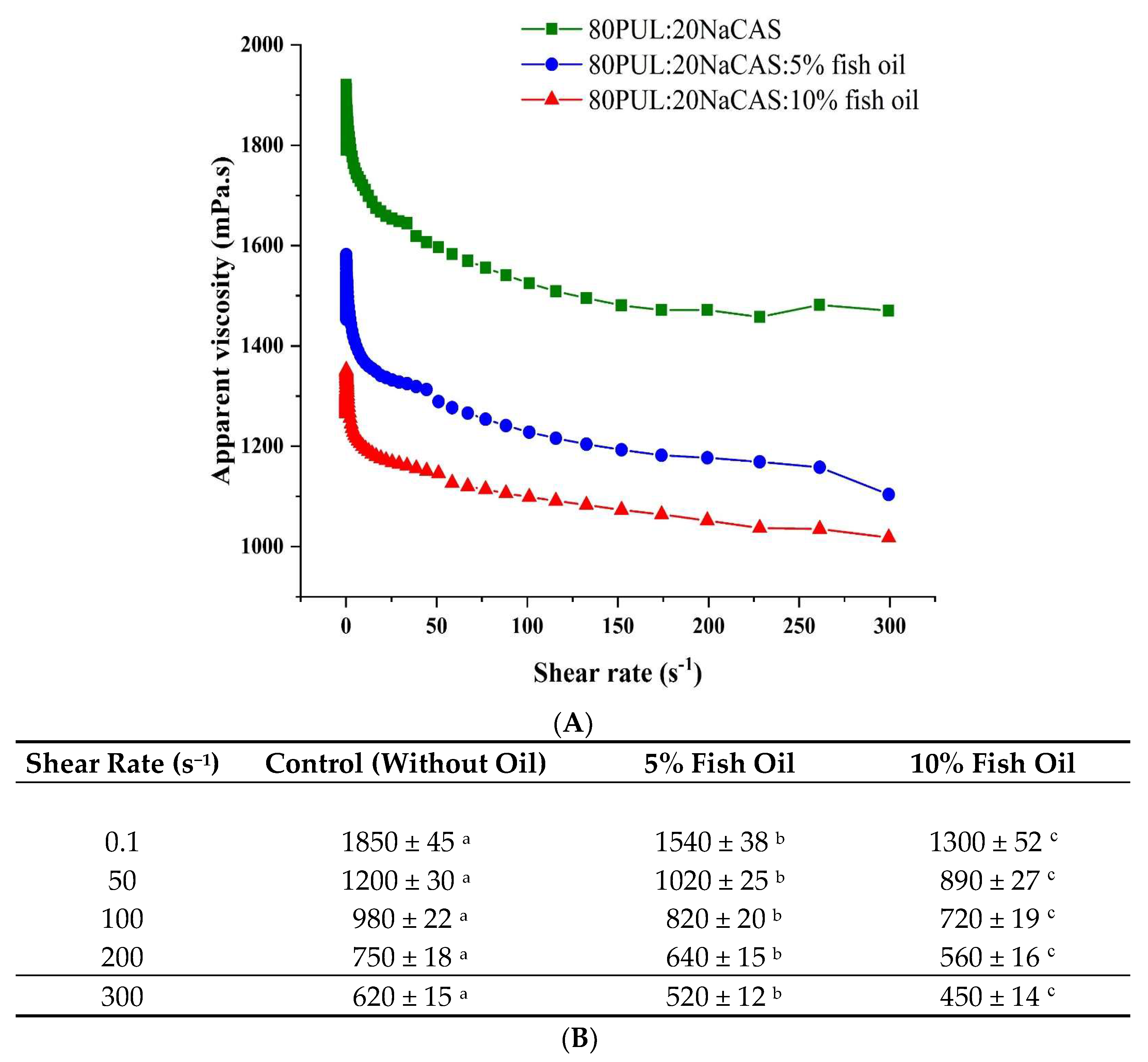

3.1.3. Viscosity

3.2. Nanofiber Characterizations

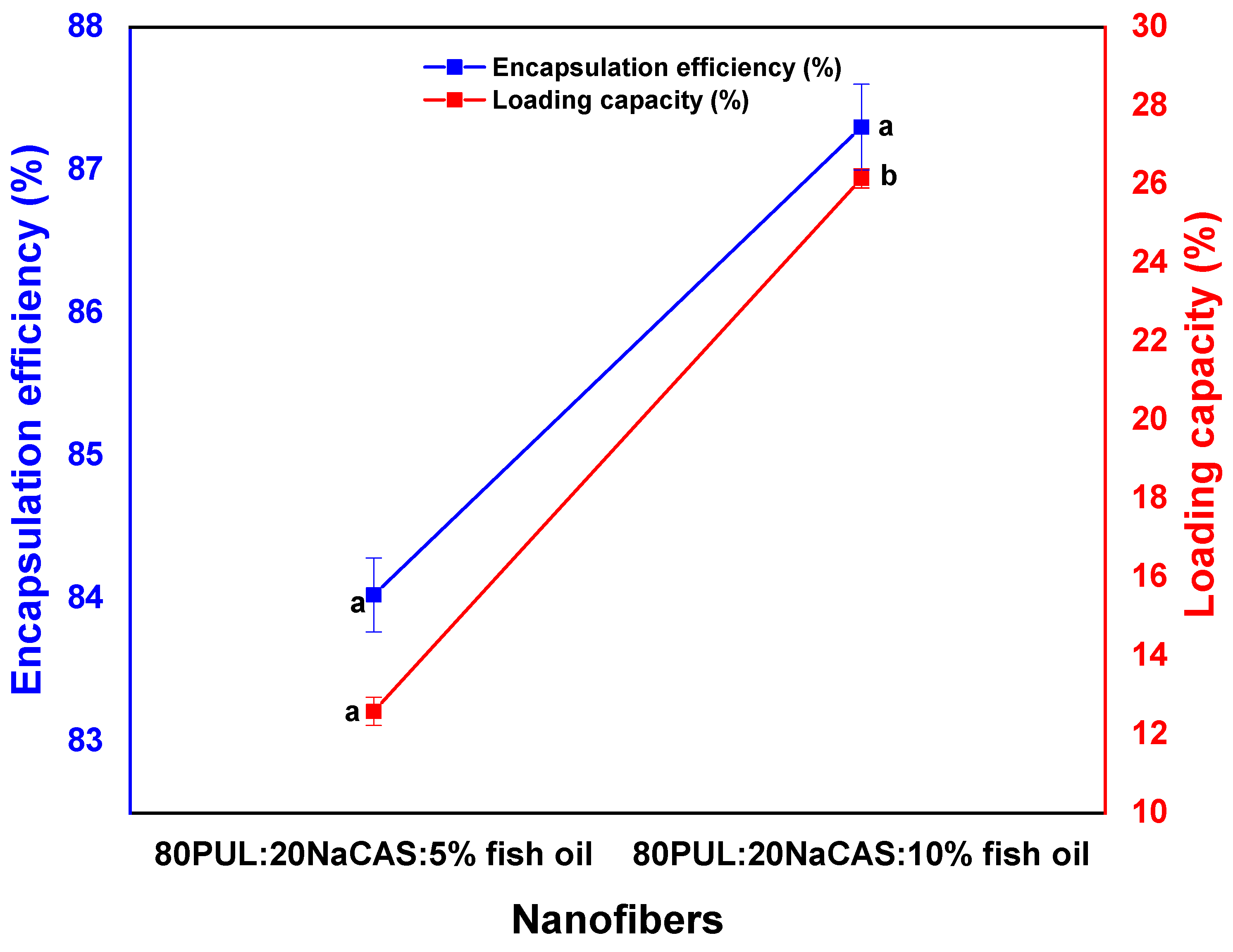

3.2.1. Encapsulation Efficiency and Loading Capacity

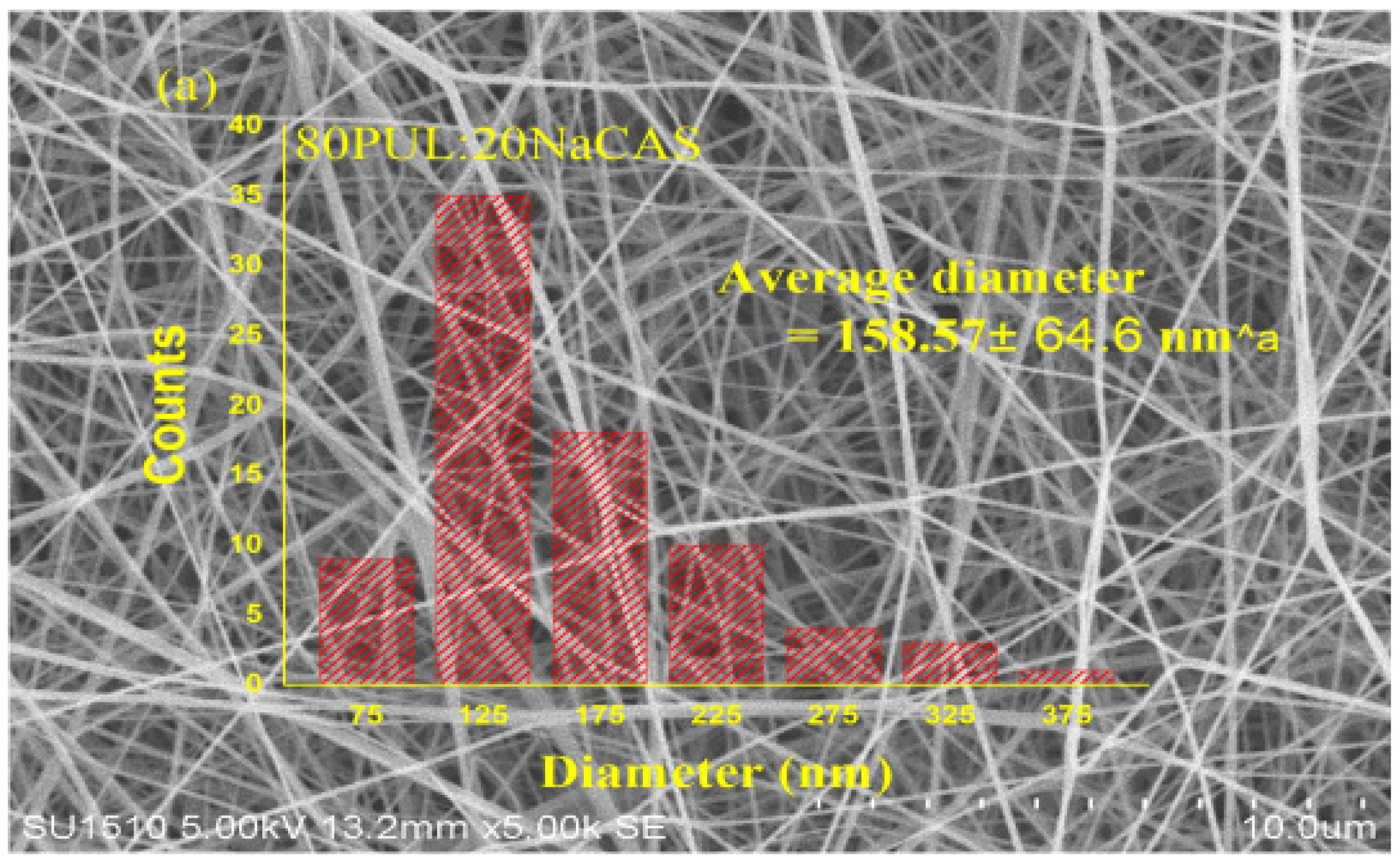

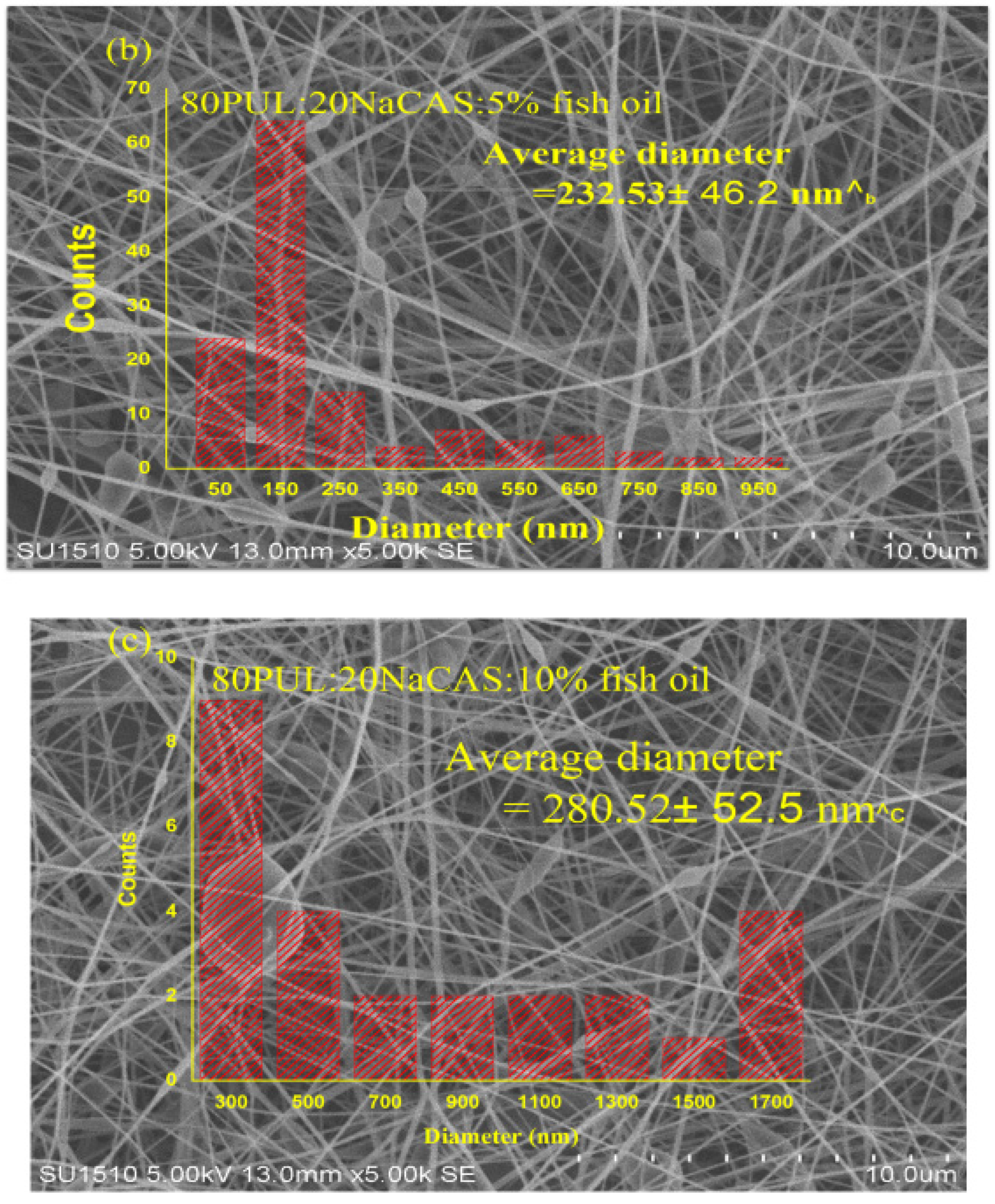

3.2.2. Morphological Features by SEM

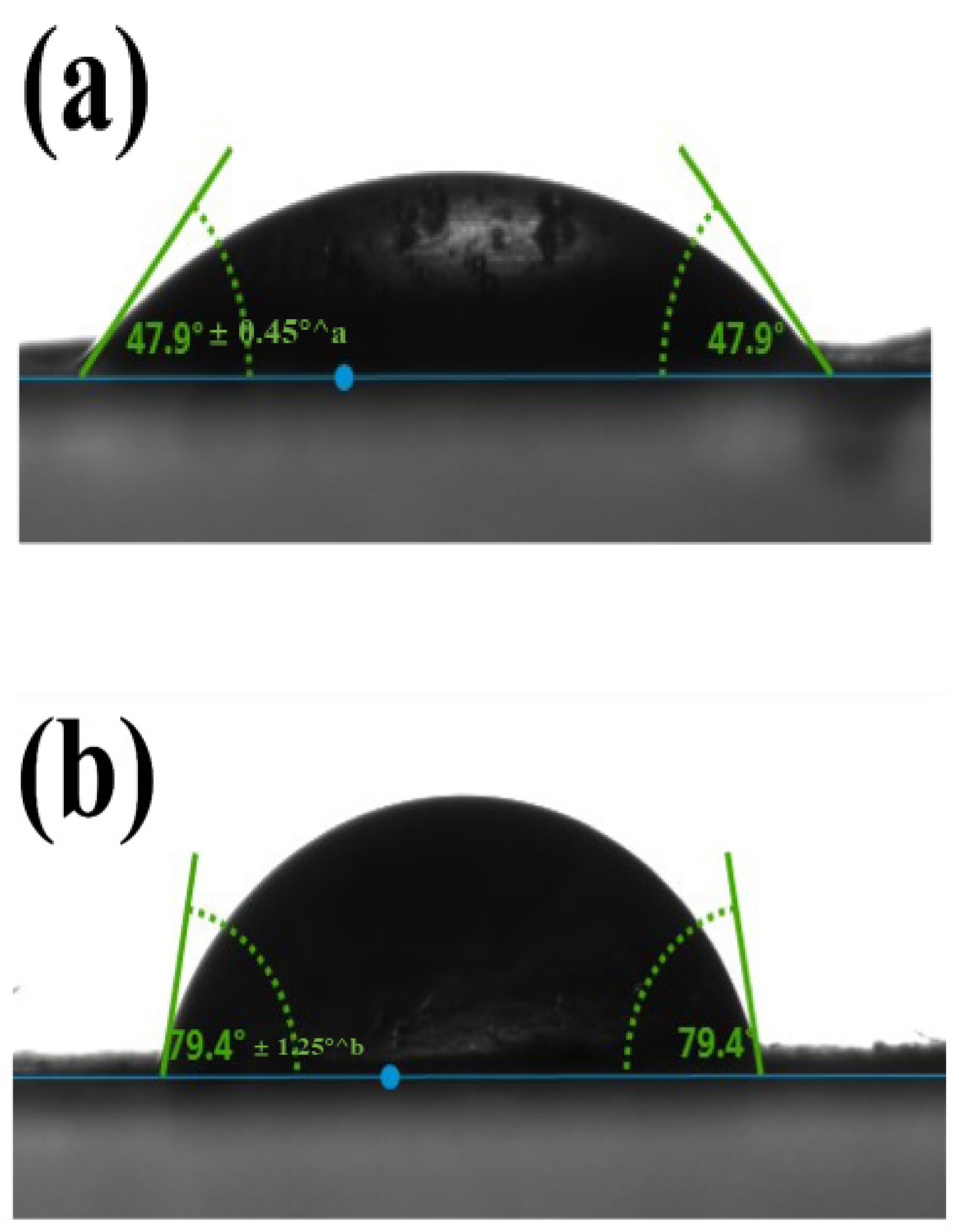

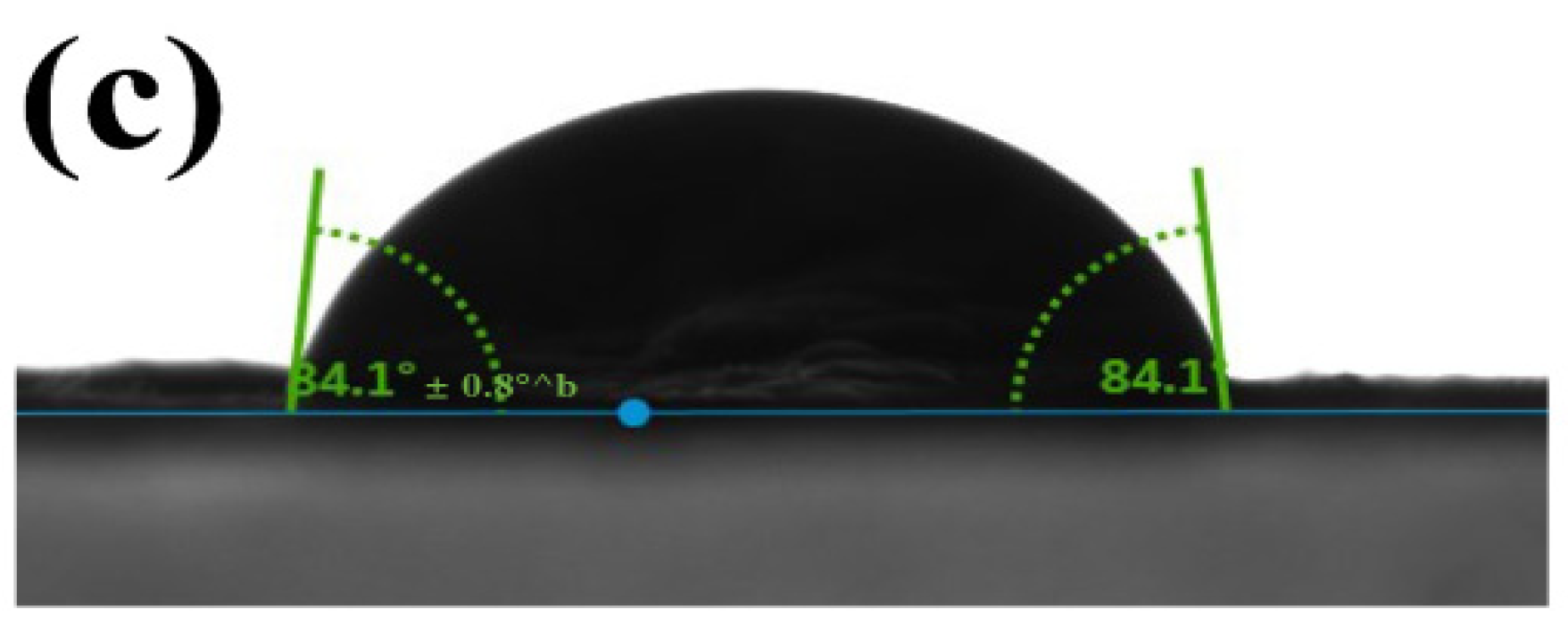

3.2.3. Wettability of the Nanofibers by Water Contact Angle

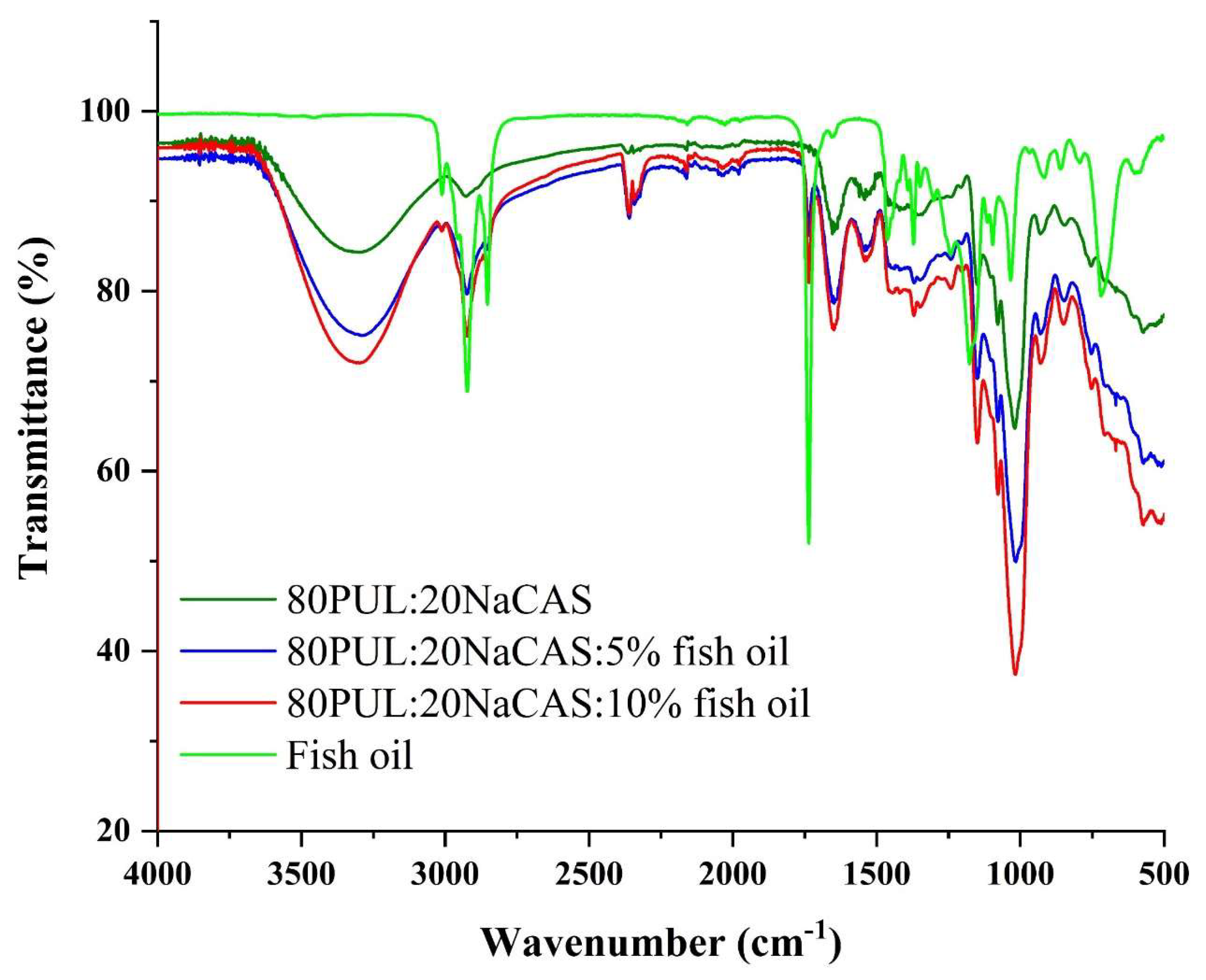

3.2.4. Chemical Structure by FTIR

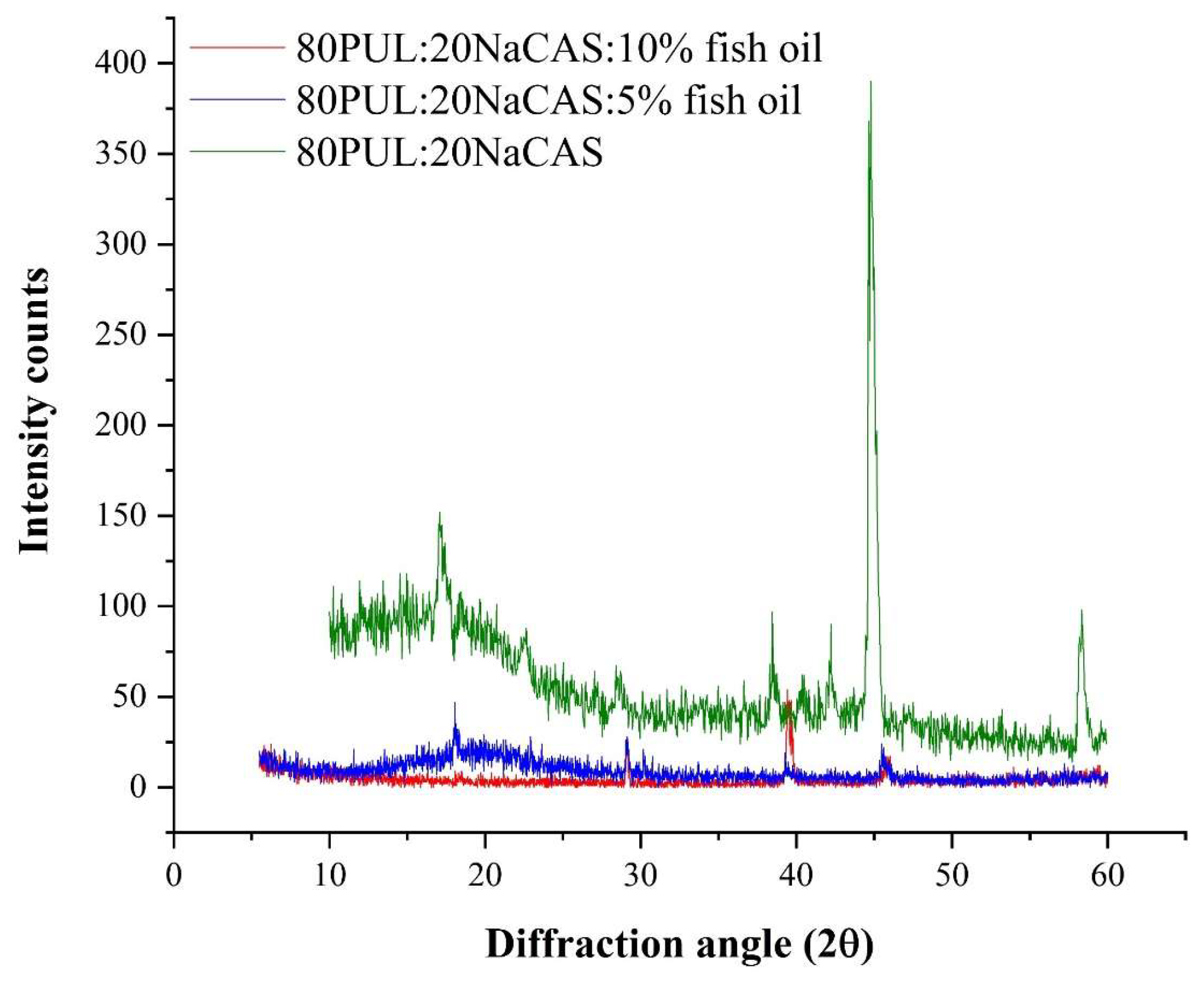

3.2.5. Crystallinity by XRD

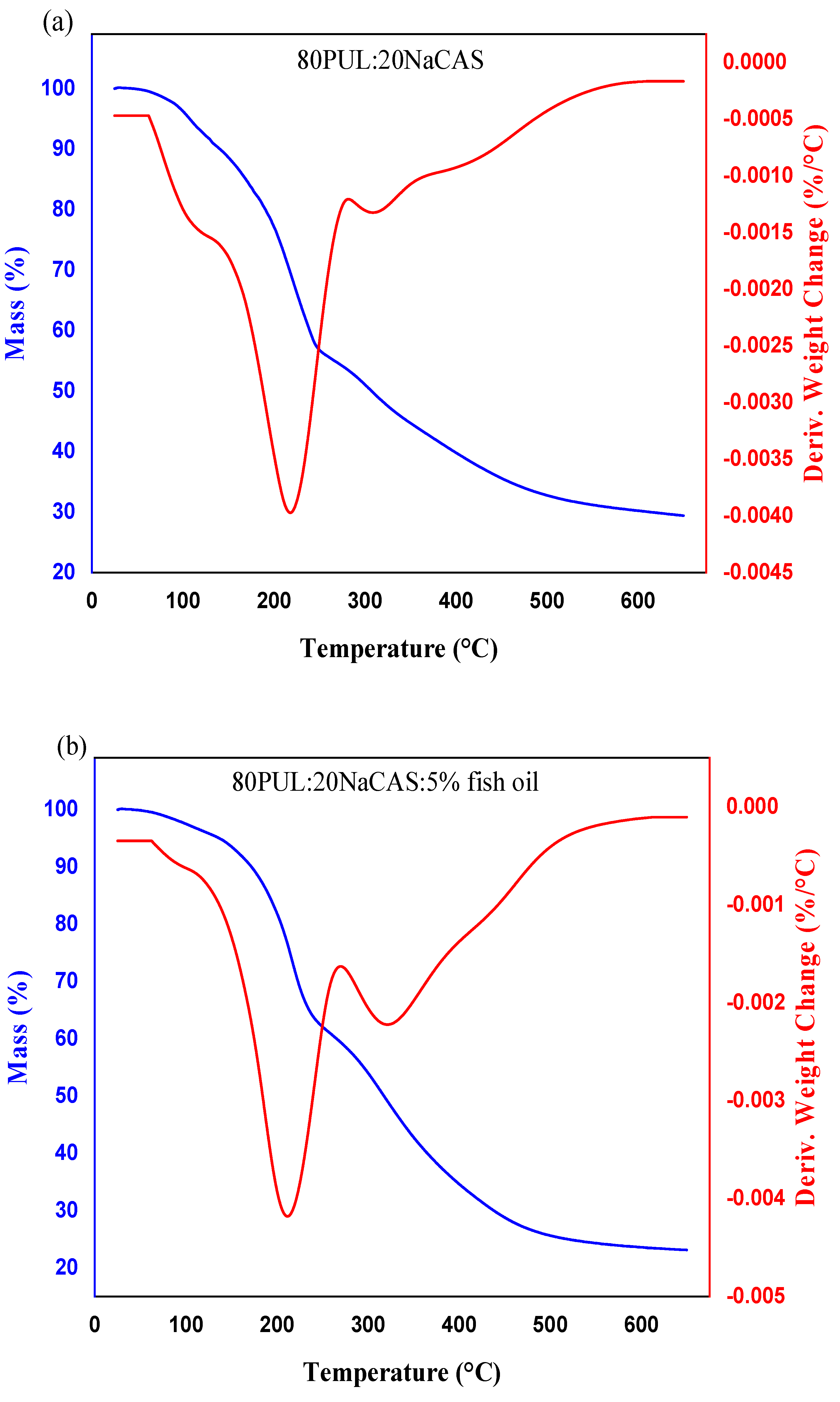

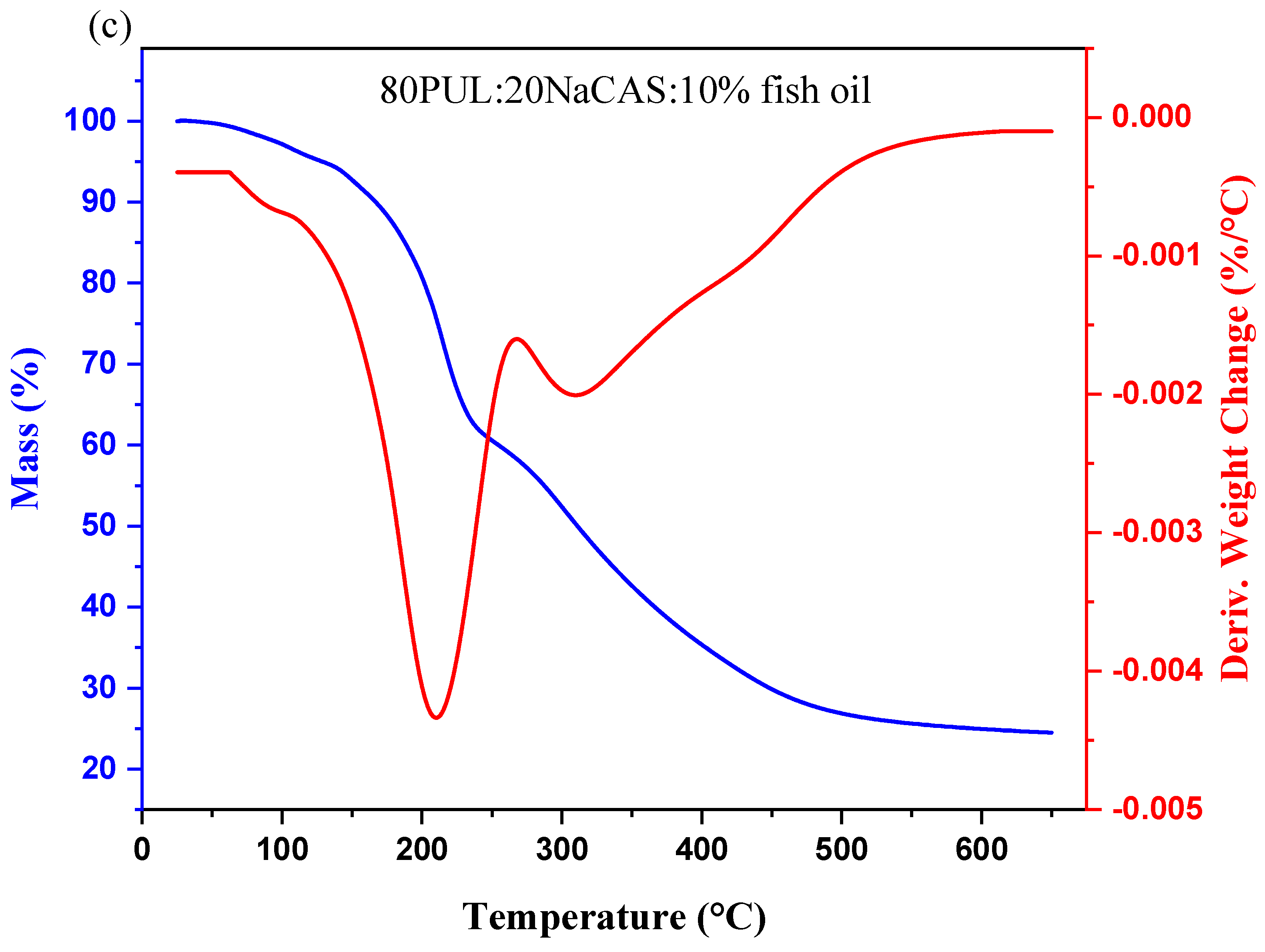

3.2.6. Thermal Stability

3.2.7. Bioactive Properties

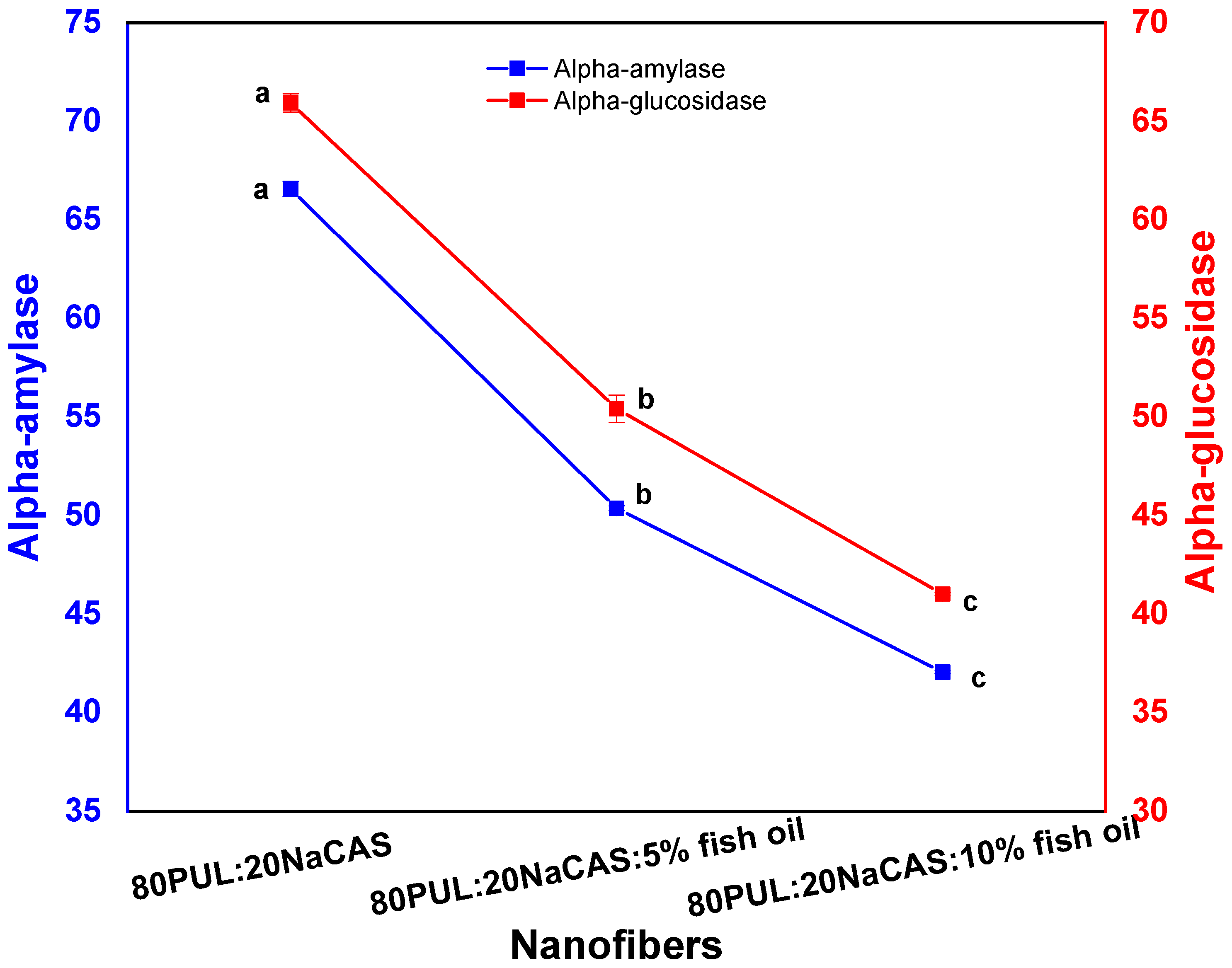

3.2.8. Antidiabetic Activity

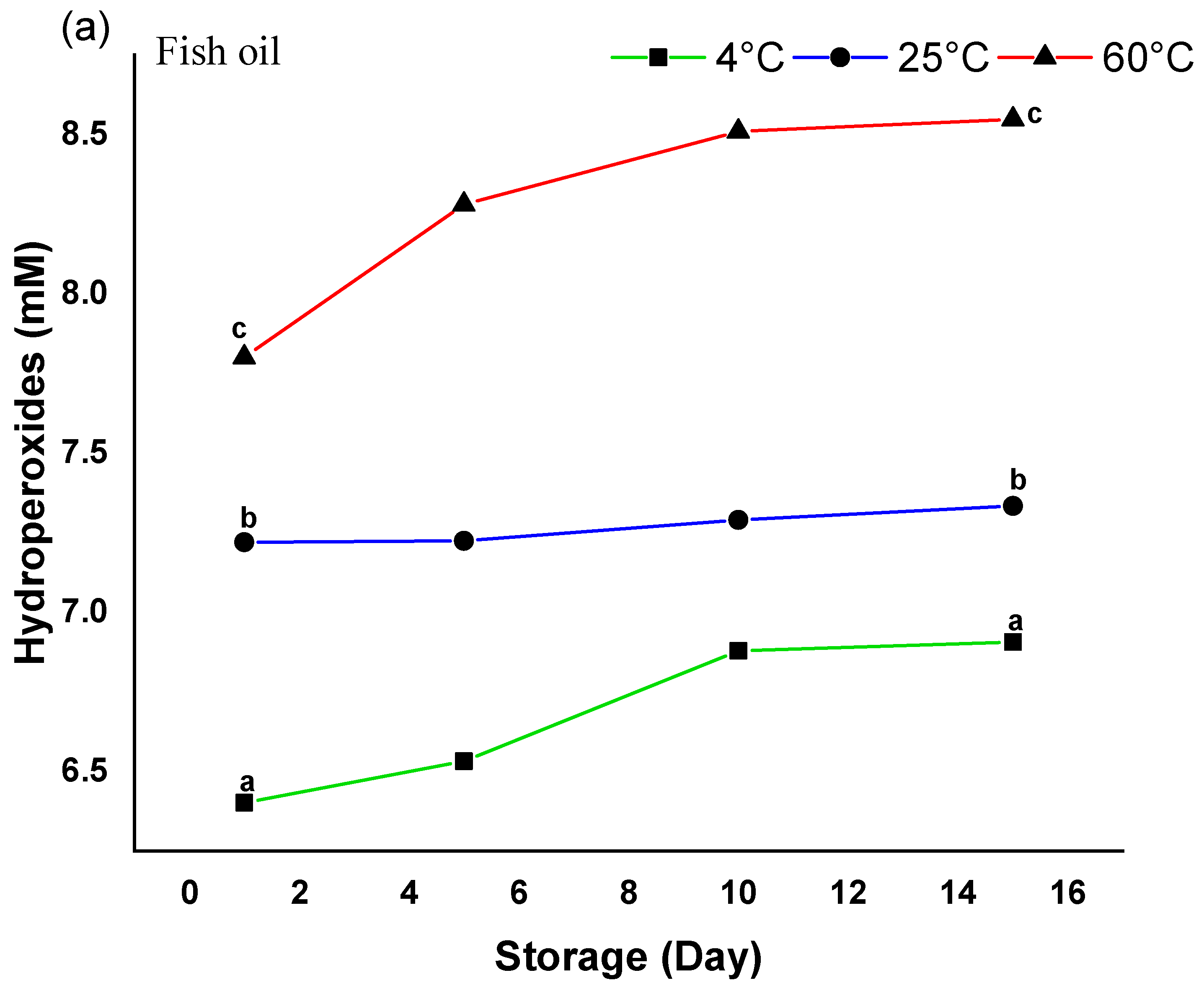

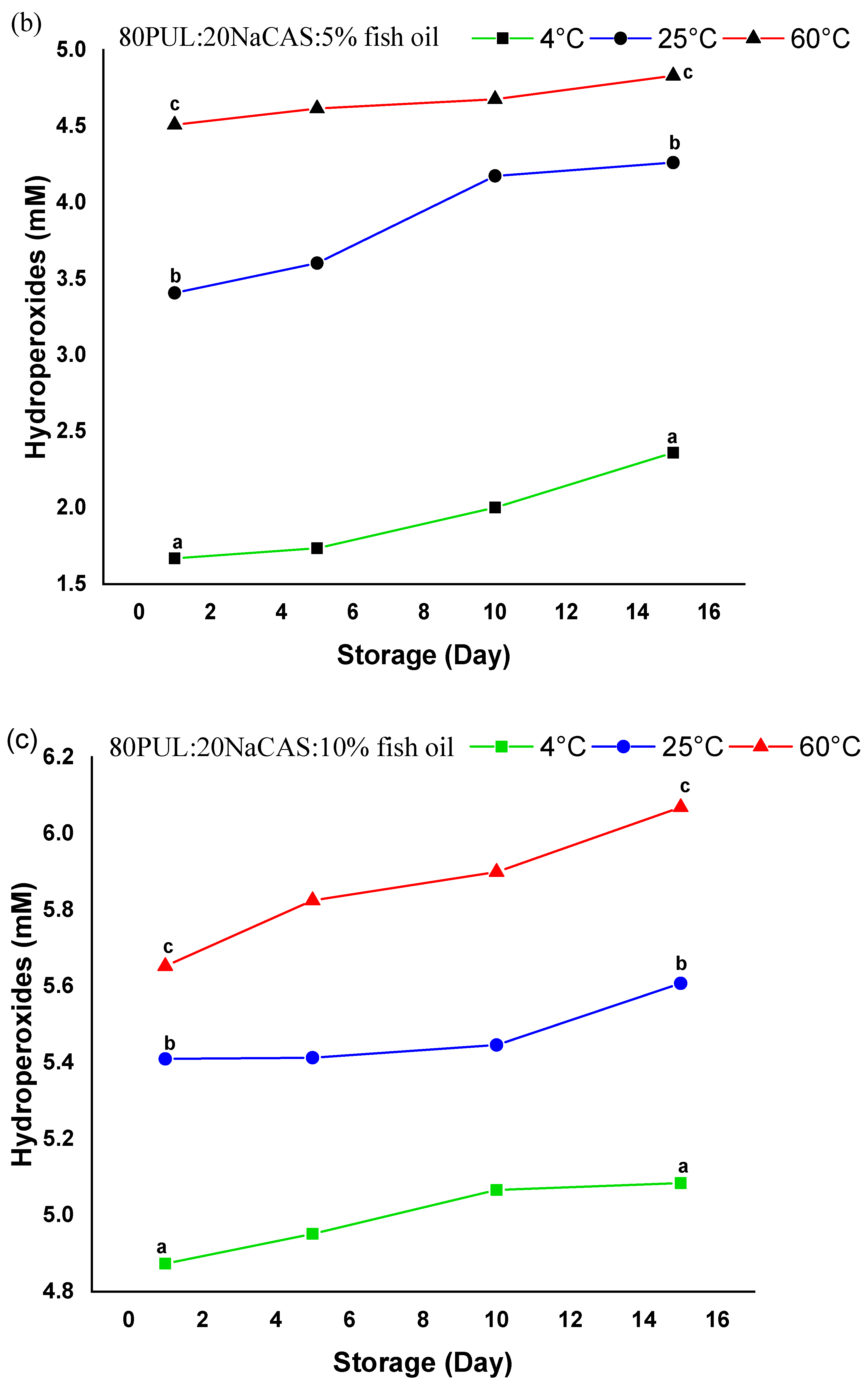

3.2.9. Oxidative Stability

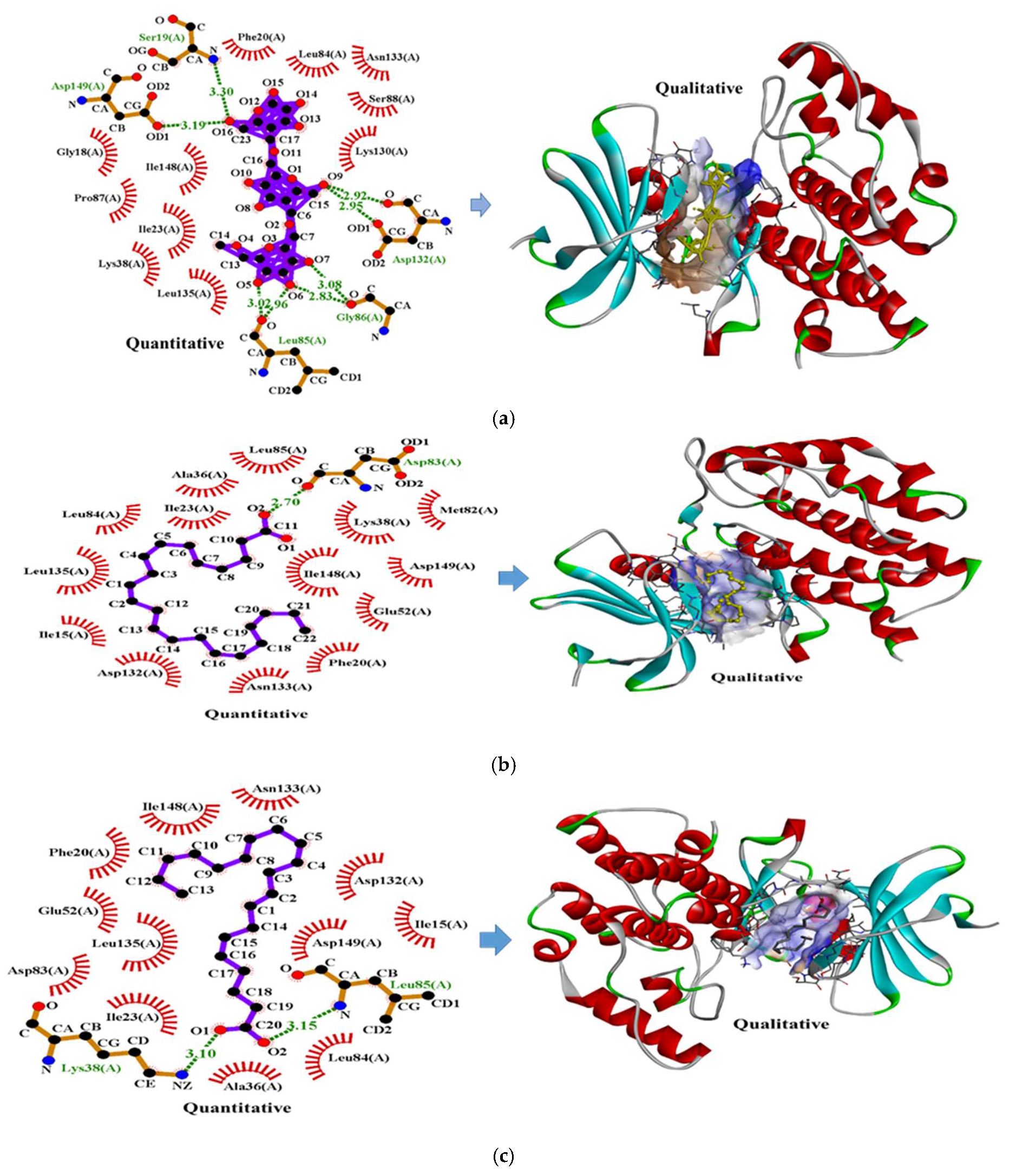

3.2.10. MD-Density Functional Theory Simulation (DFT)

Molecular Docking Analysis

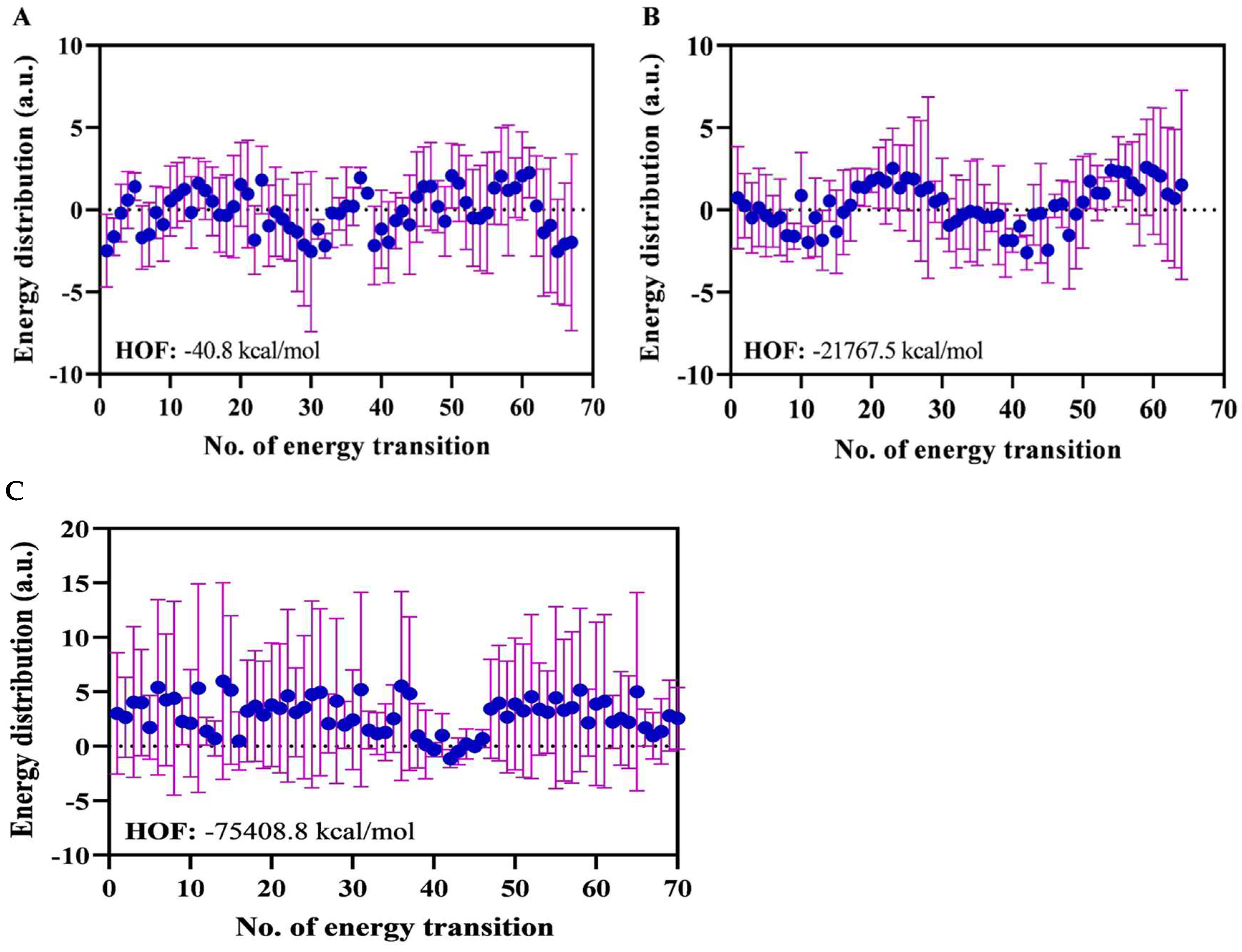

Frontier Molecular Orbital Analysis and Electronic Stability

Atomic Energy Distribution as a Basis for Thermodynamic Assessment

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saini, R.K.; Prasad, P.; Sreedhar, R.V.; Akhilender Naidu, K.; Shang, X.; Keum, Y.S. Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (PUFAs): Emerging Plant and Microbial Sources, Oxidative Stability, Bioavailability, and Health Benefits—A Review. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzan, A.J.; Garcia, P.H.D.; Furlan, C.P.B.; Barba, F.C.R.; Franco, Y.E.M.; Longato, G.B.; Contesini, F.J.; de Oliveira Carvalho, P. Oxidative stability of fish oil dietary supplements and their cytotoxic effect on cultured human keratinocytes. NFS J. 2022, 29, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdi, A.A.; Al-Maqtari, Q.A.; Mohammed, J.K.; Al-Ansi, W.; Aqeel, S.M.; Cui, H.; Lin, L. Nanoencapsulation of Mandarin Essential Oil: Fabrication, Characterization, and Storage Stability. Foods 2022, 11, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Mahdi, A.A.; Li, C.; Al-Ansi, W.; Al-Maqtari, Q.A.; Hashim, S.B.H.; Cui, H. Enhancing the properties of Litsea cubeba essential oil/peach gum/polyethylene oxide nanofibers packaging by ultrasonication. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2022, 34, 100951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moomand, K.; Lim, L.-T. Oxidative stability of encapsulated fish oil in electrospun zein fibres. Food Res. Int. 2014, 62, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabora, S.; Jiang, B.; Mahdi, A.A.; Ali, K.; Tahir, A.B. Replacing pullulan with sodium caseinate to enhance the properties of pullulan nanofibres. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 59, 4930–4938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, W.; Gharsallaoui, A.; Dumas, E.; Elaissari, A. Understanding of the key factors influencing the properties of emulsions stabilized by sodium caseinate. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 5291–5317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saghaee, R.; Ariaii, P.; Motamedzadegan, A. Development of electrospun whey protein isolate nanofiber mat for omega-3 nanoencapsulation: Microstructural and physical property analysis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 301, 140273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdulhussain, R.; Adebisi, A.; Conway, B.R.; Asare-Addo, K. Electrospun nanofibers: Exploring process parameters, polymer selection, and recent applications in pharmaceuticals and drug delivery. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2023, 90, 105156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xie, B.; Liu, Q.; Kong, B.; Wang, H. Fabrication and characterization of a novel polysaccharide based composite nanofiber films with tunable physical properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 236, 116054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premi, M.; Sharma, H.K. Effect of different combinations of maltodextrin, gum arabic and whey protein concentrate on the encapsulation behavior and oxidative stability of spray dried drumstick (Moringa oleifera) oil. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 105, 1232–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdi, A.A.; Al-Maqtari, Q.A.; Al-Ansi, W.; Hu, W.; Hashim, S.B.H.; Cui, H.; Lin, L. Replacement of polyethylene oxide by peach gum to produce an active film using Litsea cubeba essential oil and its application in beef. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 241, 124592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Feng, K.; Wen, P.; Zong, M.-H.; Lou, W.-Y.; Wu, H. Enhancing oxidative stability of encapsulated fish oil by incorporation of ferulic acid into electrospun zein mat. LWT 2017, 84, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Li, X.; Zhao, J.; Kong, B.; Wang, H.; Liu, Q.; Wang, H. Fabrication and characterization of crosslinked pea protein isolated/pullulan/allicin electrospun nanofiber films as potential active packaging material. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2022, 33, 100873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Jia, X.; Liu, Q.; Kong, B.; Wang, H. Enhancing physical properties of chitosan/pullulan electrospinning nanofibers via green crosslinking strategies. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 247, 116734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Zhong, F.; Li, Y.; Shoemaker, C.F.; Xia, W. Preparation and characterization of pullulan–chitosan and pullulan–carboxymethyl chitosan blended films. Food Hydrocoll. 2013, 30, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, S.; Thangam, R.; Fathima, N.N. Electrospinning of casein nanofibers with silver nanoparticles for potential biomedical applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 120, 1674–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Maqtari, Q.A.; Alkawry, T.A.A.; Odjo, K.; Al-Gheethi, A.A.S.; Ghamry, M.; Mahdi, A.A.; Al-Ansi, W.; Yao, W. Improving the shelf life of tofu using chitosan/gelatin-based films incorporated with Pulicaria jaubertii extract microcapsules. Prog. Org. Coat. 2023, 183, 107722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, K.; Jiang, B.; Ashraf, W.; Bin Tahir, A.; ul Haq, F. Improving the functional characteristics of thymol-loaded pullulan and whey protein isolate-based electrospun nanofiber. Food Biosci. 2024, 57, 103620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdi, A.A.; Al-Maqtari, Q.A.; Mohammed, J.K.; Al-Ansi, W.; Cui, H.; Lin, L. Enhancement of antioxidant activity, antifungal activity, and oxidation stability of Citrus reticulata essential oil nanocapsules by clove and cinnamon essential oils. Food Biosci. 2021, 43, 101226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, D.; Paul, P.K.; Al Azad, S.; Al Mazid, M.F.; Khan, A.M.; Sharif, M.A.; Rahman, M.H. Molecular optimization, docking, and dynamic simulation profiling of selective aromatic phytochemical ligands in blocking the SARS-CoV-2 S protein attachment to ACE2 receptor: An in silico approach of targeted drug designing. J. Adv. Vet. Anim. Res. 2021, 8, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabin, A.; Uddin, M.F.; Al Azad, S.; Rahman, A.; Tabassum, F.; Sarker, P.; Morshed, A.H.; Rahman, S.; Raisa, F.F.; Sakib, M.R. Target-specificity of different amyrin subunits in impeding HCV influx mechanism inside the human cells considering the quantum tunnel profiles and molecular strings of the CD81 receptor: A combined in silico and in vivo study. In Silico Pharmacol. 2023, 11, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdausi, N.; Islam, S.; Rimti, F.H.; Quayum, S.T.; Arshad, E.M.; Ibnat, A.; Islam, T.; Arefin, A.; Ema, T.I.; Biswas, P. Point-specific interactions of isovitexin with the neighboring amino acid residues of the hACE2 receptor as a targeted therapeutic agent in suppressing the SARS-CoV-2 influx mechanism. J. Adv. Vet. Anim. Res. 2022, 9, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nipun, T.S.; Ema, T.I.; Mia, M.A.R.; Hossen, M.S.; Arshe, F.A.; Ahmed, S.Z.; Masud, A.; Taheya, F.F.; Khan, A.A.; Haque, F. Active site-specific quantum tunneling of hACE2 receptor to assess its complexing poses with selective bioactive compounds in co-suppressing SARS-CoV-2 influx and subsequent cardiac injury. J. Adv. Vet. Anim. Res. 2021, 8, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, P.K.; Al Azad, S.; Rahman, M.H.; Farjana, M.; Uddin, M.R.; Dey, D.; Mahmud, S.; Ema, T.I.; Biswas, P.; Anjum, M. Catabolic profiling of selective enzymes in the saccharification of non-food lignocellulose parts of biomass into functional edible sugars and bioenergy: An in silico bioprospecting. J. Adv. Vet. Anim. Res. 2022, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.H.; Al Azad, S.; Uddin, M.F.; Farzana, M.; Sharmeen, I.A.; Kabbo, K.S.; Jabin, A.; Rahman, A.; Jamil, F.; Srishti, S.A. WGS-based screening of the co-chaperone protein DjlA-induced curved DNA binding protein A (CbpA) from a new multidrug-resistant zoonotic mastitis-causing Klebsiella pneumoniae strain: A novel molecular target of selective flavonoids. Mol. Divers. 2023, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefin, A.; Ismail Ema, T.; Islam, T.; Hossen, S.; Islam, T.; Al Azad, S.; Uddin Badal, N.; Islam, A.; Biswas, P.; Alam, N.U.; et al. Target specificity of selective bioactive compounds in blocking alpha-dystroglycan receptor to suppress Lassa virus infection: An in silico approach. J. Biomed. Res. 2021, 35, 459–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Madadi, M.; Al Azad, S.; Qiao, Y.; Elsayed, M.; Aghbashlo, M.; Tabatabaei, M. Unraveling the mechanisms underlying lignin and xylan dissolution in recyclable biphasic catalytic systems. Fuel 2024, 363, 130890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Azad, S.; Madadi, M.; Rahman, A.; Sun, C.; Zhang, E.; Sun, F. Quantum mechanical insights into lignocellulosic biomass fractionation through an naoh-catalyzed triton-x 100 system: In vitro and in silico approaches. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 5516–5530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Madadi, M.; Al Azad, S.; Lu, X.; Yan, H.; Zhou, Q.; Sun, C.; Sun, F. Unveiling the mechanisms of mixed surfactant synergy in passivating lignin-cellulase interactions during lignocellulosic saccharification. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 681, 404–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madadi, M.; Kargaran, E.; Al Azad, S.; Saleknezhad, M.; Zhang, E.; Sun, F. Machine learning-driven optimization of biphasic pretreatment conditions for enhanced lignocellulosic biomass fractionation. Energy 2025, 326, 136241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Azad, S.; Madadi, M.; Rahman, A.; Sun, C.; Sun, F. Machine learning-driven optimization of pretreatment and enzymatic hydrolysis of sugarcane bagasse: Analytical insights for industrial scale-up. Fuel 2025, 390, 134682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupikowska-Stobba, B.; Domagała, J.; Kasprzak, M.M. Critical Review of Techniques for Food Emulsion Characterization. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, W.; Elaissari, A.; Dumas, E.; Gharsallaoui, A. Effect of trans-cinnamaldehyde or citral on sodium caseinate: Interfacial rheology and fluorescence quenching properties. Food Chem. 2023, 400, 134044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi Bonakdar, M.; Rodrigue, D. Electrospinning: Processes, structures, and materials. Macromol 2024, 4, 58–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culler, M.D.; Inchingolo, R.; McClements, D.J.; Decker, E.A. Impact of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Dilution and Antioxidant Addition on Lipid Oxidation Kinetics in Oil/Water Emulsions. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2021, 69, 750–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, G.; Liu, Z.; Shi, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, J.; Xia, G. Effects of sodium caseinate/tannic acid stabilization of high internal phase fish oil emulsions on surimi gel properties and 3D printing quality. LWT 2025, 220, 117580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez Ortiz, D.; Pochat-Bohatier, C.; Cambedouzou, J.; Bechelany, M.; Miele, P. Current Trends in Pickering Emulsions: Particle Morphology and Applications. Engineering 2020, 6, 468–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Admawi, H.K.; Mohammed, A.A. A comprehensive review of emulsion liquid membrane for toxic contaminants removal: An overview on emulsion stability and extraction efficiency. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 109936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, B.N.; Pedersen, T.L.; Fojan, P. Electrospinning with Droplet Generators: A Method for Continuous Electrospinning of Emulsion Fibers. J. Self Assem. Mol. Electron. 2022, 2022, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadaf, A.; Gupta, A.; Hasan, N.; Fauziya; Ahmad, S.; Kesharwani, P.; Ahmad, F.J. Recent update on electrospinning and electrospun nanofibers: Current trends and their applications. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 23808–23828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, M.; Zhou, K.; Sun, Z.; Xiong, Z.; Du, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, L.; Hou, J. Rheological characterization and shear viscosity prediction of heavy oil-in-water emulsions. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 381, 121782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClements, D.J.; Jafari, S.M. Improving emulsion formation, stability and performance using mixed emulsifiers: A review. Adv. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2018, 251, 55–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, F.T.; Ghafoor, K.; Ferdosh, S.; Al-Juhaimi, F.; Ali, E.; Yunus, K.B.; Hamed, M.H.; Islam, A.; Asif, M.; Sarker, M.Z.I. Microencapsulation of fish oil using supercritical antisolvent process. J. Food Drug Anal. 2017, 25, 654–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopač, T.; Ručigaj, A.; Krajnc, M. Effect of polymer-polymer interactions on the flow behavior of some polysaccharide-based hydrogel blends. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 287, 119352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, E.; Golding, M. Rheology of sodium caseinate stabilized oil-in-water emulsions. J. Colloid. Interface Sci. 1997, 191, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülseren, İ.; Corredig, M. Changes in colloidal properties of oil in water emulsions stabilized with sodium caseinate observed by acoustic and electroacoustic spectroscopy. Food Biophys. 2011, 6, 534–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luis, A.; Ramos, A.; Domingues, F. Pullulan Films Containing Rockrose Essential Oil for Potential Food Packaging Applications. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Tian, Z. Preparation and Characterization of Pullulan-Based Packaging Paper for Fruit Preservation. Molecules 2024, 29, 1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Moreno, P.J.; Stephansen, K.; van der Kruijs, J.; Guadix, A.; Guadix, E.M.; Chronakis, I.S.; Jacobsen, C. Encapsulation of fish oil in nanofibers by emulsion electrospinning: Physical characterization and oxidative stability. J. Food Eng. 2016, 183, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Chen, G.; Chang, B.P.; Mekonnen, T.H. Recent progress in the development of porous polymeric materials for oil ad/absorption application. RSC Appl. Polym. 2024, 3, 43–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bascuas, S.; Morell, P.; Hernando, I.; Quiles, A. Recent trends in oil structuring using hydrocolloids. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 118, 106612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeles, M.; Cheng, H.L.; Velankar, S.S. Emulsion electrospinning: Composite fibers from drop breakup during electrospinning. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2007, 19, 728–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, L.-T. 7-Electrospinning and Electrospraying Technologies for Food and Packaging Applications. In Electrospun Polymers and Composites; Dong, Y., Baji, A., Ramakrishna, S., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Duxford, UK, 2021; pp. 217–259. [Google Scholar]

- García-Moreno, P.J.; Özdemir, N.; Stephansen, K.; Mateiu, R.V.; Echegoyen, Y.; Lagaron, J.M.; Chronakis, I.S.; Jacobsen, C. Development of carbohydrate-based nano-microstructures loaded with fish oil by using electrohydrodynamic processing. Food Hydrocoll. 2017, 69, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, J.; Zou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H. Stable encapsulation of camellia oil in core–shell zein nanofibers fabricated by emulsion electrospinning. Food Chem. 2023, 429, 136860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Moreno, P.J.; Damberg, C.; Chronakis, I.S.; Jacobsen, C. Oxidative stability of pullulan electrospun fibers containing fish oil: Effect of oil content and natural antioxidants addition. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2017, 119, 1600305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabu Mathew, S.; Jaiswal, A.K.; Jaiswal, S. A comprehensive review on hydrophobic modification of biopolymer composites for food packaging applications. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2025, 48, 101464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballon, A.; Queiroz, L.S.; de Lamo-Castellví, S.; Güell, C.; Ferrando, M.; Jacobsen, C.; Yesiltas, B. Physical and oxidative stability of 5% fish oil-in-water emulsions stabilized with lesser mealworm (Alphitobius diaperinus larva) protein hydrolysates pretreated with ultrasound and pulsed electric fields. Food Chem. 2025, 476, 143339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, M.; Lee, W.; Song, W.J.; Im, J. Electrospun polycaprolactone fibers encapsulating omega-3 and montelukast sodium to prevent capsular contracture in breast implant surgery. Int. J. Pharm. 2025, 679, 125744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.w.; Qin, Z.y.; Xu, J.x.; Kong, B.h.; Liu, Q.; Wang, H. Preparation and characterization of pea protein isolate-pullulan blend electrospun nanofiber films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 157, 641–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmmed, F.; Gordon, K.C.; Killeen, D.P.; Fraser-Miller, S.J. Detection and Quantification of Adulteration in Krill Oil with Raman and Infrared Spectroscopic Methods. Molecules 2023, 28, 3695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, K.; Yang, Y.; Zheng, B.; Yu, Q.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, N.; Rama, S.M.; Zhang, X.; Ye, J.; Xiao, M. Enhancing Pullulan Soft Capsules with a Mixture of Glycerol and Sorbitol Plasticizers: A Multi-Dimensional Study. Polymers 2023, 15, 2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vongsvivut, J.; Heraud, P.; Zhang, W.; Kralovec, J.A.; McNaughton, D.; Barrow, C.J. Quantitative determination of fatty acid compositions in micro-encapsulated fish-oil supplements using Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy. Food Chem. 2012, 135, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaneva, Z.; Ivanova, D. Catechins within the Biopolymer Matrix—Design Concepts and Bioactivity Prospects. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, H.; Sung, M.; Baek, H.; Lee, S.; Seo, B.; Shin, K.; Noh, M.; Jang, J.; Bae Lee, J.; Woong Kim, J. Tailored lipid crystallization in confined microparticle domains through alkyl chains infiltration from cellulose nanofiber surfactants. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 486, 149701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Clarkson, C.M.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Lamm, M.; Pang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Qian, J.; Tajvidi, M.; Gardner, D.J.; et al. Alignment of Cellulose Nanofibers: Harnessing Nanoscale Properties to Macroscale Benefits. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 3646–3673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.-H.; Chen, H.-L.; Dong, J.-R. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLNs) and Nanostructured Lipid Carriers (NLCs) as Food-Grade Nanovehicles for Hydrophobic Nutraceuticals or Bioactives. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giorgio, L.; Salgado, P.R.; Mauri, A.N. Encapsulation of fish oil in soybean protein particles by emulsification and spray drying. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 87, 891–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurazzi, N.M.; Asyraf, M.R.M.; Rayung, M.; Norrrahim, M.N.F.; Shazleen, S.S.; Rani, M.S.A.; Shafi, A.R.; Aisyah, H.A.; Radzi, M.H.M.; Sabaruddin, F.A.; et al. Thermogravimetric Analysis Properties of Cellulosic Natural Fiber Polymer Composites: A Review on Influence of Chemical Treatments. Polymers 2021, 13, 2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeoti, I.A.; Hawboldt, K.; Santos, M.R. Thermal and flow properties of fish oil blends with bunker fuel oil. Fuel 2015, 158, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, A.; Shams, R.; Dash, K.K.; Shaikh, A.M.; Kovács, B. Protein-polysaccharide complexes and conjugates: Structural modifications and interactions under diverse treatments. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 18, 101510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermund, D.; Jacobsen, C.; Chronakis, I.S.; Pelayo, A.; Yu, S.; Busolo, M.; Lagaron, J.M.; Jónsdóttir, R.; Kristinsson, H.G.; Akoh, C.C.; et al. Stabilization of Fish Oil-Loaded Electrosprayed Capsules with Seaweed and Commercial Natural Antioxidants: Effect on the Oxidative Stability of Capsule-Enriched Mayonnaise. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2019, 121, 1800396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, K.; Liu, F.; He, X.; Ma, P.; Mao, L.; Gao, Y.; Yuan, F. The effect of sterol derivatives on properties of soybean and egg yolk lecithin liposomes: Stability, structure and membrane characteristics. Food Res. Int. 2018, 109, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, K. Omega-3 Fatty Acid Intake Lowers Risk of Diabetic Retinopathy. Am. J. Nurs. 2017, 117, 60–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirbas, Z.; Altay, F. Incorporating antioxidative peptides within nanofibrous delivery vehicles: Characterization and in vitro release kinetics. Food Biosci. 2023, 53, 102660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnwal, A.; Kumar, G.; Singh, R.; Selvaraj, M.; Malik, T.; Al Tawaha, A.R.M. Natural biopolymers in edible coatings: Applications in food preservation. Food Chem. X 2025, 25, 102171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, N.; Puluhulawa, L.E.; Cindana Mo’o, F.R.; Rusdin, A.; Gazzali, A.M.; Budiman, A. Potential of Pullulan-Based Polymeric Nanoparticles for Improving Drug Physicochemical Properties and Effectiveness. Polymers 2024, 16, 2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, L.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Study on the molecular interactions of hydroxylated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons with catalase using multi-spectral methods combined with molecular docking. Food Chem. 2020, 309, 125743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, M.; Shi, T.; Monto, A.R.; Yuan, L.; Jin, W.; Gao, R. Enhancement of the gelling properties of Aristichthys nobilis: Insights into intermolecular interactions between okra polysaccharide and myofibrillar protein. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2024, 9, 100814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruchunan, U.; Henry, C.J.; Sim, S.Y.J. Role of protein-lipid interactions for food and food-based applications. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 160, 110715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Li, S.; Su, W.; Pan, K.; Peng, F. Non-covalent interaction of sacha inchi protein and quercetin: Mechanism and physicochemical property. Food Chem. X 2025, 26, 102296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbari, Z.; Stagno, C.; Iraci, N.; Efferth, T.; Omer, E.A.; Piperno, A.; Montazerozohori, M.; Feizi-Dehnayebi, M.; Micale, N. Biological evaluation, DFT, MEP, HOMO-LUMO analysis and ensemble docking studies of Zn(II) complexes of bidentate and tetradentate Schiff base ligands as antileukemia agents. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1301, 137400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dabora, S.; Jiang, B.; Hlaing, K.S.S. Encapsulation of Fish Oil in Pullulan/Sodium Caseinate Nanofibers: Fabrication, Characterization, and Oxidative Stability. Foods 2025, 14, 3677. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14213677

Dabora S, Jiang B, Hlaing KSS. Encapsulation of Fish Oil in Pullulan/Sodium Caseinate Nanofibers: Fabrication, Characterization, and Oxidative Stability. Foods. 2025; 14(21):3677. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14213677

Chicago/Turabian StyleDabora, Suaad, Bo Jiang, and Khin Su Su Hlaing. 2025. "Encapsulation of Fish Oil in Pullulan/Sodium Caseinate Nanofibers: Fabrication, Characterization, and Oxidative Stability" Foods 14, no. 21: 3677. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14213677

APA StyleDabora, S., Jiang, B., & Hlaing, K. S. S. (2025). Encapsulation of Fish Oil in Pullulan/Sodium Caseinate Nanofibers: Fabrication, Characterization, and Oxidative Stability. Foods, 14(21), 3677. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14213677