The Role of Fermentation and Drying on the Changes in Bioactive Properties, Seconder Metabolites, Fatty Acids and Sensory Properties of Green Jalapeño Peppers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Material

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Titratable Acidity, pH and Salt Content

| Fermented Pepper | |||

| pH | 3.38 | ± | 0.01 |

| Acidity (%) | 0.09 | ± | 0.00 |

| Salt content (g/100 mL) | 6.02 | ± | 0.08 |

- ±: standard deviation.

2.2.2. Moisture Amount

2.2.3. Protein Analysis

2.2.4. Carotenoid Content

2.2.5. Extraction Procedure

2.2.6. Determination of Total Phenol

2.2.7. Total Flavonoid Content

2.2.8. Determination of Antioxidant Activity

DPPH Free Radical Scavenging Activity

Ferric-Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP)

2.2.9. Determination of Phenolic Compounds

2.2.10. Oil Contents

2.2.11. Fatty Acid Composition

2.2.12. Macro- and Microelement Analysis of Jalapeño Pepper Samples

2.2.13. Sensorial Properties

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physicochemical and Bioactive Properties of Fermented and Dried Jalapeño Peppers

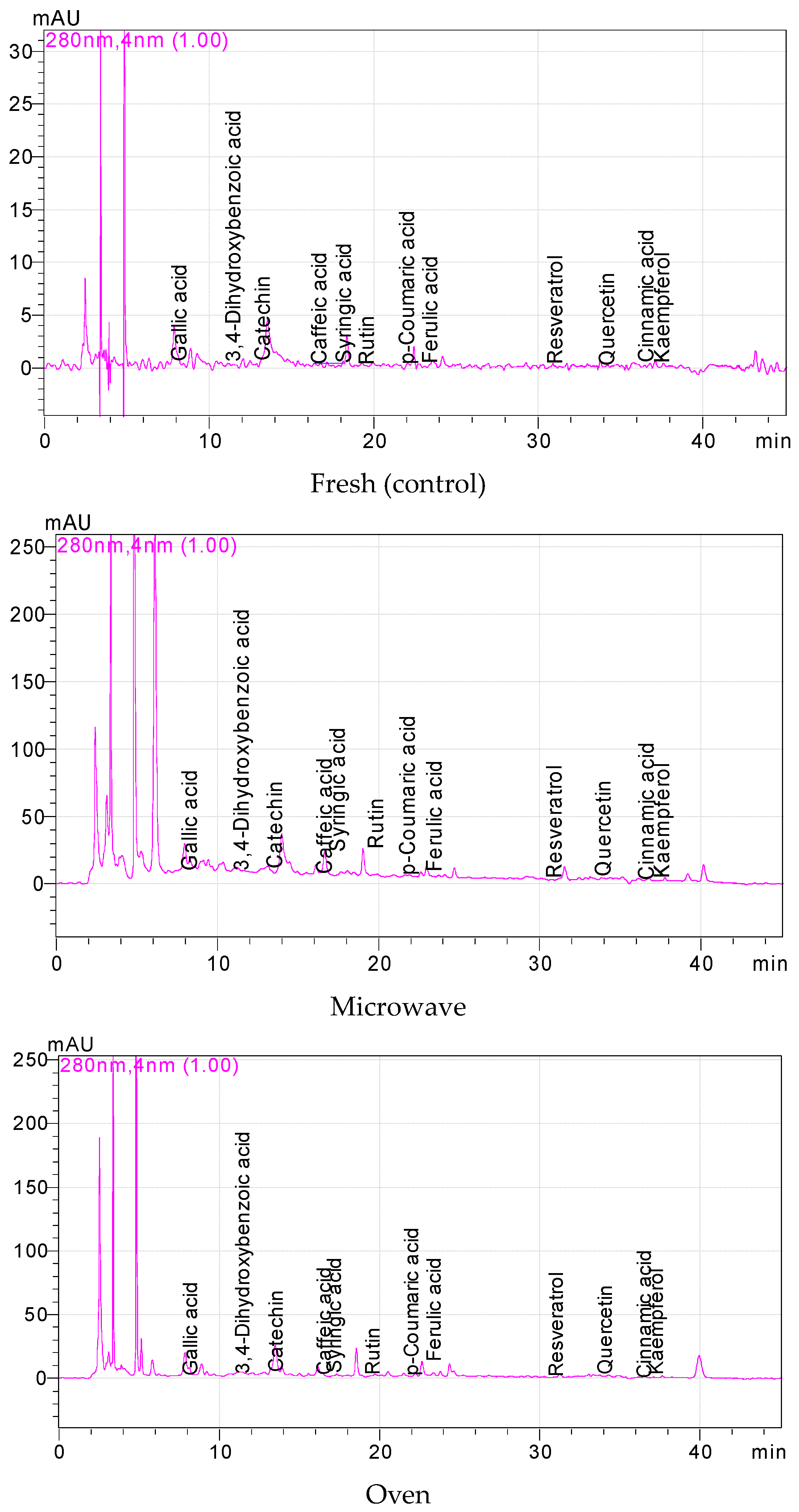

3.2. The Phenolics of Fresh, Fermented and Dried Jalapeño Peppers

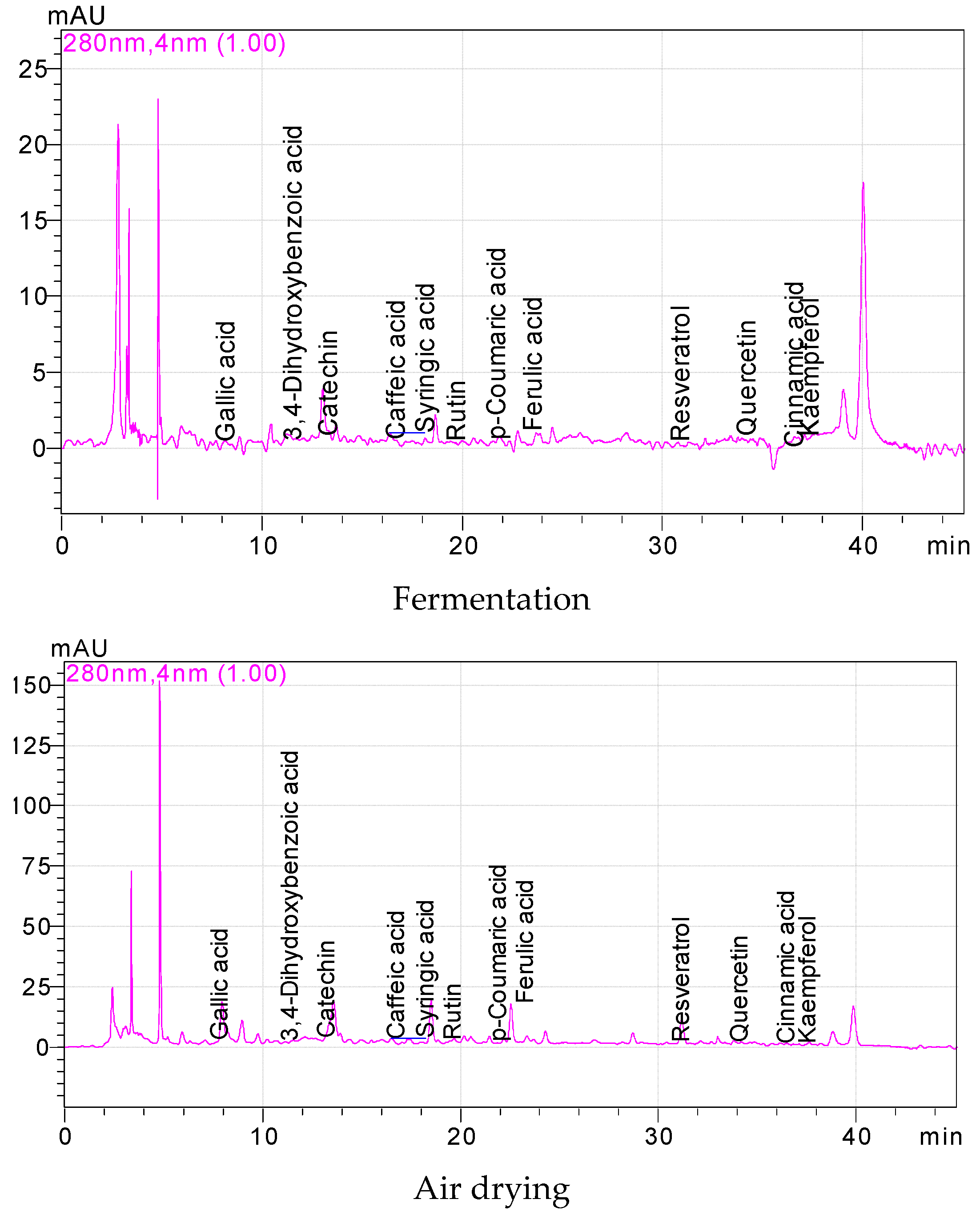

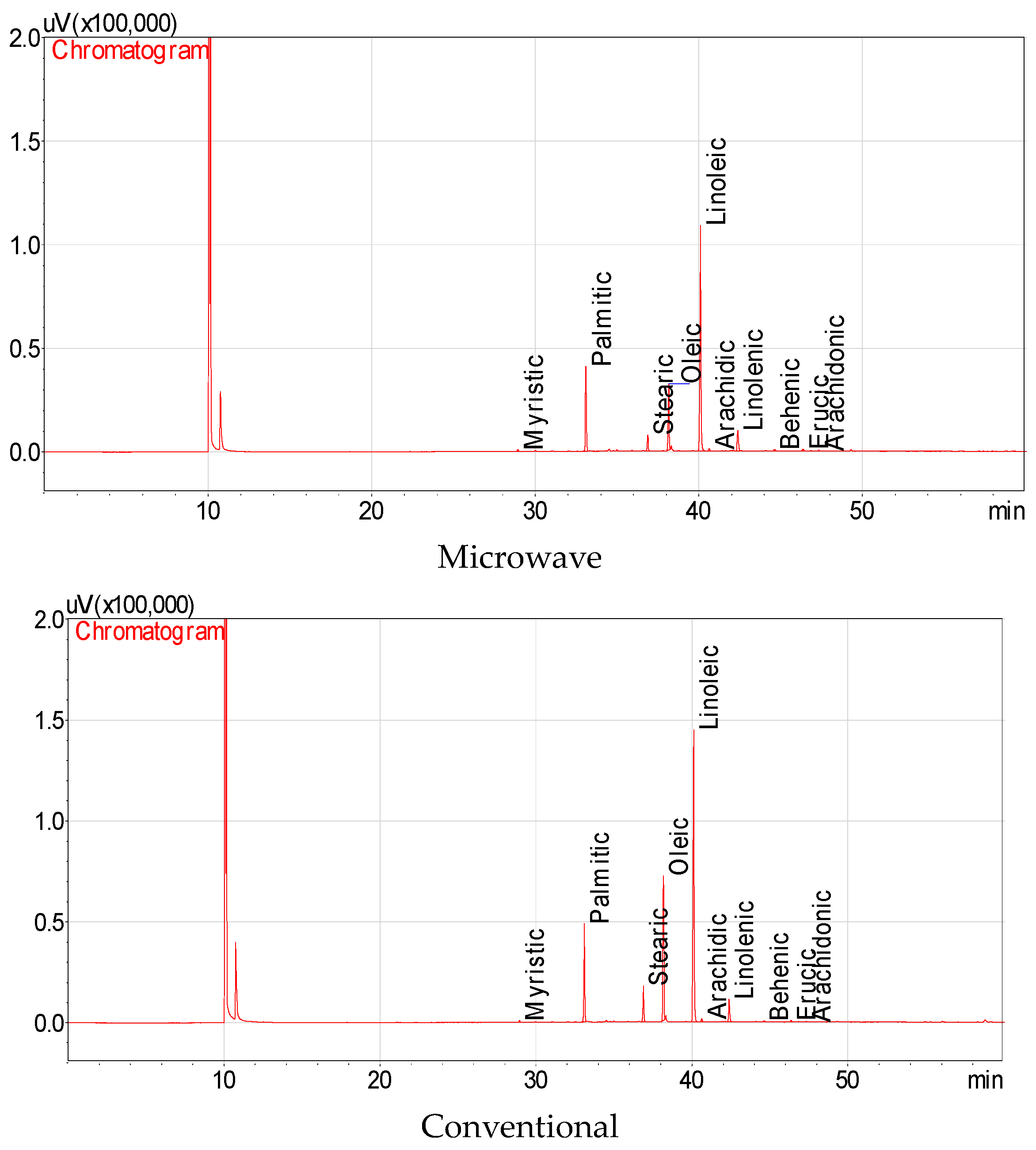

3.3. The Fatty Acids of Fresh, Fermented and Dried Jalapeño Pepper Oils

3.4. The Protein and Mineral Results of Fresh, Fermented and Dried Jalapeño Peppers

3.5. The Sensory Evaluations of Fermented Jalapeño Peppers

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sandoval-Oliveros, R.; Guevara-Olvera, L.; Beltrán, J.P.; Gómez-Mena, C.; Acosta-García, G. Developmental landmarks during floral ontogeny of jalapeño chili pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) and the effect of gibberellin on ovary growth. Plant Reproduct. 2017, 30, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamed, M.; Kalita, D.; Bartolo, M.E.; Jayanty, S.S. Capsaicinoids, Polyphenols and Antioxidant Activities of Capsicum annuum: Comparative Study of the Effect of Ripening Stage and Cooking Methods. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez-Parrilla, E.; de la Rosa, L.A.; Amarowicz, R.; Shahidi, F. Antioxidant Activity of Fresh and Processed Jalapeño and Serrano Peppers. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 59, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, C.; Nicácio, A.; Jardim, I.; Visentainer, J.; Maldaner, L. Determination of Phenolic Compounds in Red Sweet Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) Using a Modified QuEChERS Method and UHPLC-MS/MS Analysis and Its Relation to Antioxidant Activity. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2019, 30, 1229–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Ma, K.; Tian, M. Chemical composition and nutritive value of hot pepper seed (Capsicum annuum) grown in Northeast Region of China. Food Sci. Technol. Camp. 2015, 35, 659–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, T.; Akpınar, Ö. Biological activities of phytochemicals in plants. Turk. J. Agric. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 8, 1734–1746. [Google Scholar]

- Que, F.; Mao, L.; Fang, X.; Wu, T. Comparison of hot air drying and freeze-drying on the physicochemical properties and antioxidant activities of pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata Duch.) flours. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2008, 43, 1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Gálvez, A.; Di Scala, K.; Rodríguez, K.; Lemus-Mondaca, R.; Miranda, M.; López, J.; Perez-Won, M. Effect of air-drying temperature on physico-chemical properties, antioxidant capacity, colour and total phenolic content of red pepper (Capsicum annuum, L. var. Hungarian). Food Chem. 2009, 117, 647–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MEGEP. Gıda Teknolojisi Turşu Çeşitleri Üretimi; TC Milli Eğitim Bakanlığı, Mesleki Eğitim ve Öğretim Sisteminin Güçlendirilmesi Projesi: Ankara, Turkey, 2007.

- Coşkun, F.; Arıcı, M. Sütlü Biber Turşusu Yapımı Üzerine Bir Araştırma. Akad. Guda Derg 2005, 3, 13–15. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, A.H.; de Castro, A.; López-López, A.; Cortés-Delgado, A.; Beato, V.M.; Montaño, A. Retention of color and volatile compounds of Spanish-style green table olives pasteurized and stored in plastic containers under conditions of constant temperature. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 75, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis, 15th ed.; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Washington, DC, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- da Rocha, A.S.; Rocha, E.K.; Alves, L.M.; de Moraes, B.A.; de Castro, T.C.; Albarello, N.; Simões-Gurgel, C. Production and optimization through elicitation of carotenoid pigments in the in vitro cultures of Cleome rosea Vahl (Cleomaceae). J. Plant Biochem. Biotechnol. 2013, 24, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, A.; Syazwanie, N.F.; Mahmod, N.H.; Badaluddin, N.A.; Mustafa, K.; Alias, N.; Aslani, F.; Prodhan, M.A. Evaluation of antioxidant compounds, antioxidant activities and capsaicinoid compounds of Chili (Capsicum sp.) germplasms available in Malaysia. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants 2018, 9, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, K.M.; Lee, K.W.; Park, J.B.; Lee, H.J.; Hwang, I.K. Variation in major antioxidants and total antioxidant activity of Yuzu (Citrus junos Sieb ex Tanaka) during maturation and between cultivars. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 5907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogan, S.; Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Zoecklein, B.; Zhou, K. Antioxidant properties and bioactive components of Norton (Vitis aestivalis) and Cabernet Franc (Vitis vinifera) wine grapes. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2009, 42, 1269–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.K.; Mbwambo, Z.H.; Chung, H.; Luyengi, L.; Gamez, E.J.; Mehta, R.G.; Kinghorn, A.D.; Pezzuto, J.M. Evaluation of the antioxidant potential of natural products. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 1998, 1, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudenuti, N.V.d.R.; de Camargo, A.C.; de Alencar, S.M.; Danielski, R.; Shahidi, F.; Madeira, T.B.; Hirooka, E.Y.; Spinosa, W.A.; Grossmann, M.V.E. Phenolics and alkaloids of raw cocoa nibs and husk: The role of soluble and insoluble-bound antioxidants. Food Biosci. 2021, 42, 101085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Multari, S.; Marsol-Vall, A.; Heponiemi, P.; Suomela, J.-P.; Yang, B. Changes in the volatile profile, fatty acid composition and other markers of lipid oxidation of six different vegetable oils during short-term deep-frying. Food Res. Int. 2019, 122, 318–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tošić, S.B.; Mitić, S.S.; Velimirović, D.S.; Stojanović, G.S.; Pavlović, A.N.; Pecev-Marinković, E.T. Elemental composition of edible nuts: Fast optimization and validation procedure of an ICP-OES method. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2014, 95, 2271–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhoudi, R.; Mehrnia, M.A.; Lee, D.-J. Antioxidant activities and bioactive compounds of five Jalopeno peppers (Capsicum annuum) cultivars. Nat. Prod. Res. 2017, 33, 871–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Materska, M. Bioactive phenolics of fresh and freeze-dried sweet and semi-spicy pepper fruits (Capsicum annuum L.). J. Funct. Foods 2014, 7, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Rios, A.K.; Medina-Juarez, L.A.; Gamez-Meza, N. Drying and pickling on phenols, capsaicinoids, and free radical-scavenging activity in Anaheim and Jalapeño peppers. Ciênc. Rural. Santa Maria 2017, 47, e20160722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ruiz-Cruz, S.; Alvarez-Parrilla, E.; de laRosa, L.A.; Martinez-Gonzalez, A.I.; Ornelas-Paz, J.J.; Mendoza-Wilson, A.M.; Gonzalez-Aguilar, G.A. Effect of different sanitizers on microbial, sensory and nutritional quality of fresh-cut jalapeno peppers. Am. J. Agric. Biol. Sci. 2010, 5, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Juárez, L.A.; Molina-Quijada, D.M.; Del Toro-Sánchez, C.L.; González-Aguilar, G.A.; Gámez-Meza, N. Antioxidant activity of peppers (Capsicum annuum L.) extracts and characterization of their phenolic constituents. Interciencia 2012, 37, 588–593. [Google Scholar]

- Eseceli, H.; Değirmencioğlu, A.; Kahraman, R. Omega yağ asitlerinin insan sağliği yönünden önem. In Proceedings of the Türkiye 9. Gıda Kongresi, Bolu, Türkiye, 24–26 May 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Guil-Guerrero, J.L.; Martinez-Guirado, C.; del Mar Rebolloso-Fuentes, M.; Carrique-P’erez, A. Nutrient composition and antioxidant activity of 10 pepper (Capsicum annuun) varieties. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2006, 224, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anuroopa, A.R.; Sreenivas, V.K. Comparative evaluatıon of nutritional and pungency qualitiesof selected chilli cultıvars. Agric Res. J. 2021, 58, 921–926. [Google Scholar]

- Ogunlade, I.; Alebiosu, A.; Osasona, A. Proximate, mineral composition, antioxidant activity, and total phenolic content of some pepper varieties (Capsicum species). Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2013, 6, 2221–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Emmanuel-Ikpeme, C.; Peters, H.; Orim, A.O. Comparative evaluation of the nutritional, phytochemical and microbiological quality of three pepper varieties. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2014, 2, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.-H.; Lee, S.-Y.; Baek, D.-Y.; Park, S.-Y.; Lee, S.-G.; Ryu, T.-H.; Lee, S.-K.; Kang, H.-J.; Kwon, O.-H.; Kil, M.; et al. A comparison of the nutrient composition and statistical profile in red pepper fruits (Capsicums annuum L.) based on genetic and environmental factors. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2019, 62, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadra Khan, N.; Muhammad, J.A.; Shah Syed, Z.A.S. Comparative analysis of mineral content and proximate composition from chilli pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) germplasm. Pure Appl. Biol. 2019, 8, 1338–1347. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio, C.; Hardisson, A.; Martín, R.; Báez, A.; Martín, M.; Álvarez, R. Mineral composition of the red and green pepper (Capsicum annuum) from Tenerife Island. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2002, 214, 501–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-López, A.J.; Lópe-Nicolas, J.M.; Núñez-Delicado, E.; Amor, F.M.; Carbonell-Barrachina, A.A. Effect of agricultural practices on color, carotenoids composition, and minerals contents of sweet peppers, cv. Almuden. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 8158–8164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Process | Moisture Content (%) | Carotenoid Content (µg/g) | Oil Content (%) | Total Phenolic Content (mg/100 g) | Total Flavonoid Content (mg/100 g) | Antioxidant Activity (mmol/kg, DPPH) | Antioxidant Activity (mg/g, FRAP) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh (control) | 90.37 | ± | 0.09 a * | 8.44 | ± | 0.00 d | - | 53.35 | ± | 1.49 d | 14.17 | ± | 0.41 e | 0.44 | ± | 0.01 d | 2.41 | ± | 0.44 d | ||

| Microwave | 4.13 | ± | 0.28 e | 61.34 | ± | 0.00 b | 2.00 | ± | 0.00 c | 350.69 | ± | 5.34 a | 482.74 | ± | 9.40 a | 3.82 | ± | 0.05 c | 27.41 | ± | 1.19 a |

| Conventional | 20.51 | ± | 0.23 c | 40.94 | ± | 0.00 c | 2.60 | ± | 0.01 a | 233.43 | ± | 4.47 c | 372.50 | ± | 4.34 c | 3.91 | ± | 0.00 a | 13.69 | ± | 0.56 c |

| Fermentation | 89.31 | ± | 0.28 b | 3.38 | ± | 0.00 e | 2.40 | ± | 0.03 b | 45.81 | ± | 0.45 e | 19.17 | ± | 1.09 d | 0.23 | ± | 0.01 e | 2.23 | ± | 0.29 d,e |

| Air drying | 6.92 | ± | 0.15 d | 65.68 | ± | 0.01 a | 2.00 | ± | 0.01 c | 259.62 | ± | 2.94 b | 386.55 | ± | 8.12 b | 3.88 | ± | 0.03 b | 17.61 | ± | 1.47 b |

| Phenolic Compounds (mg/100 g) | Fresh | Microwave | Conventional | Fermentation | Air Drying | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gallic acid | 0.38 | ± | 0.02 d * | 0.45 | ± | 0.21c | 1.10 | ± | 0.36a | 0.61 | ± | 0.25 b | 0.33 | ± | 0.26e |

| 3,4-Dihydroxybenzoic acid | 0.80 | ± | 0.17 d | 11.00 | ± | 3.70a | 3.43 | ± | 0.57b | 0.43 | ± | 0.18 e | 1.86 | ± | 0.49c |

| Catechin | 1.51 | ± | 0.80 d | 44.87 | ± | 5.63a | 16.77 | ± | 4.44b | 1.36 | ± | 1.03 e | 10.00 | ± | 2.95c |

| Caffeic acid | 0.62 | ± | 0.59 c | 3.67 | ± | 1.12a | 0.47 | ± | 0.12d | 0.13 | ± | 0.04 e | 1.31 | ± | 0.42b |

| Syringic acid | 0.78 | ± | 0.74 d | 13.23 | ± | 1.75a | 2.79 | ± | 1.17b | 0.43 | ± | 0.02 e | 1.91 | ± | 0.17c |

| Rutin | 0.76 | ± | 0.60 d | 38.31 | ± | 4.55a | 2.52 | ± | 0.92c | 0.23 | ± | 0.04 e | 3.82 | ± | 0.38b |

| p- Coumaric acid | 0.04 | ± | 0.01 d | 1.58 | ± | 0.73a | 0.75 | ± | 0.44b | 0.08 | ± | 0.04 d | 0.29 | ± | 0.04c |

| Ferulic acid | 0.10 | ± | 0.02 e | 2.44 | ± | 0.57c | 3.07 | ± | 0.36b | 0.28 | ± | 0.01 d | 3.67 | ± | 0.22a |

| Resveratrol | 0.07 | ± | 0.05 c | 1.05 | ± | 0.56a | 0.15 | ± | 0.09b | 0.05 | ± | 0.03 cd | 0.55 | ± | 0.25b |

| Quercetin | 0.21 | ± | 0.04 d | 6.34 | ± | 1.15a | 1.90 | ± | 0.23b | 0.25 | ± | 0.18 d | 1.13 | ± | 0.36c |

| Cinnamic acid | 0.06 | ± | 0.03 de | 0.54 | ± | 0.20a | 0.07 | ± | 0.03d | 0.12 | ± | 0.01 b | 0.11 | ± | 0.04bc |

| Kaempferol | 0.13 | ± | 0.05 e | 3.52 | ± | 0.18a | 1.57 | ± | 0.68b | 0.40 | ± | 0.20 c | 0.31 | ± | 0.06d |

| Fatty Acids | Microwave | Conventional | Fermentation | Air Drying | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Myristic | 0.44 | ± | 0.03 a * | 0.34 | ± | 0.01 b | - ** | 0.34 | ± | 0.02 b | ||

| Palmitic | 17.25 | ± | 0.81 b | 14.28 | ± | 0.03 c | 45.17 | ± | 1.03 a | 13.54 | ± | 0.35 d |

| Stearic | 3.60 | ± | 0.08 c | 5.58 | ± | 0.00 b | 10.32 | ± | 0.04 a | 2.22 | ± | 0.03 d |

| Oleic | 14.91 | ± | 0.17 c | 22.96 | ± | 0.01 b | 29.77 | ± | 0.31 a | 9.52 | ± | 0.05 d |

| Linoleic | 56.49 | ± | 0.43 b | 51.61 | ± | 0.03 c | 10.84 | ± | 0.16 d | 68.38 | ± | 0.21 a |

| Arachidic | 0.60 | ± | 0.06 b | 0.52 | ± | 0.00 c | 1.43 | ± | 0.00 a | 0.40 | ± | 0.01 d |

| Linolenic | 5.15 | ± | 0.04 a | 3.98 | ± | 0.01 c | - | 4.82 | ± | 0.05 b | ||

| Behenic | 0.56 | ± | 0.06 a | 0.31 | ± | 0.00 c | - | 0.42 | ± | 0.01 b | ||

| Erucic | 0.75 | ± | 0.07 b | 0.34 | ± | 0.00 c | 3.19 | ± | 0.21 a | 0.23 | ± | 0.01 d |

| Arachidonic | 0.24 | ± | 0.01 a | 0.08 | ± | 0.00 c | - | 0.11 | ± | 0.00 b | ||

| Samples | Protein | P | K | Ca | Mg | S | Fe | Cu | Mn | Zn | B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh | 8.69 ± 0.10 c * | 261.96 ± 5.22 d | 2333.53 ± 14.40 a | 213.47 ± 3.22 e | 155.31 ± 3.93 d | 197.82 ± 3.30 d | 3.68 ± 0.40 d | 0.91 ± 0.03 d | 1.81 ± 0.30 c | 1.82 ± 0.06 d,e | 8.08 ± 0.29 b |

| Microwave | 12.12 ± 0.36a b | 1985.21 ± 168.01 a | 20,615.20 ± 29.87 b | 1454.17 ± 93.08 b | 972.09 ± 2.83 a | 1357.99 ± 91.48 b | 28.37 ± 2.32 b | 6.44 ± 0.73 a | 9.31 ± 1.73 b | 14.52 ± 0.89 b | 0.92 ± 0.06 d |

| Conventional | 12.22 ± 0.18 a | 1943.01 ± 81.52 c | 19,603.69 ± 602.90 c | 1461.99 ± 79.46 a | 954.57 ± 8.57 c | 1361.46 ± 68.38 a | 59.42 ± 2.17 a | 5.39 ± 0.34 b | 9.59 ± 0.84 a | 15.50 ± 0.84 a | 8.32 ± 0.31 a |

| Fermentation | 8.59 ± 0.19 d | 92.55 ± 2.45 e | 995.55 ± 3.77 e | 295.46 ± 1.17 d | 83.44 ± 2.68 e | 169.32 ± 1.76 e | 2.84 ± 0.22 e | 1.05 ± 0.04 c | 0.94 ± 0.05 d | 1.84 ± 0.27 d | 7.25 ± 0.88 c |

| Air drying | 11.64 ± 0.40 b | 1947.19 ± 1.88 b | 17,645.89 ± 1037.47 d | 1361.39 ± 24.73 c | 964.17 ± 6.18 b | 1334.14 ± 2.28 c | 25.47 ± 0.85 c | 6.33 ± 0.55 a | 9.64 ± 1.38 a | 13.48 ± 0.93 c | 0.89 ± 0.04 e |

| Properties | Fermented Jalapeño Pepper | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Flavor | 4.83 | ± | 0.41 |

| Odor | 3.83 | ± | 1.33 |

| Color | 4.83 | ± | 0.41 |

| Texture | 4.83 | ± | 0.41 |

| Pepperiness | 4.50 | ± | 0.84 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mohamed Ahmed, I.A.; AlJuhaimi, F.; Özcan, M.M.; Uslu, N.; Walayat, N. The Role of Fermentation and Drying on the Changes in Bioactive Properties, Seconder Metabolites, Fatty Acids and Sensory Properties of Green Jalapeño Peppers. Processes 2024, 12, 2291. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr12102291

Mohamed Ahmed IA, AlJuhaimi F, Özcan MM, Uslu N, Walayat N. The Role of Fermentation and Drying on the Changes in Bioactive Properties, Seconder Metabolites, Fatty Acids and Sensory Properties of Green Jalapeño Peppers. Processes. 2024; 12(10):2291. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr12102291

Chicago/Turabian StyleMohamed Ahmed, Isam A., Fahad AlJuhaimi, Mehmet Musa Özcan, Nurhan Uslu, and Noman Walayat. 2024. "The Role of Fermentation and Drying on the Changes in Bioactive Properties, Seconder Metabolites, Fatty Acids and Sensory Properties of Green Jalapeño Peppers" Processes 12, no. 10: 2291. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr12102291

APA StyleMohamed Ahmed, I. A., AlJuhaimi, F., Özcan, M. M., Uslu, N., & Walayat, N. (2024). The Role of Fermentation and Drying on the Changes in Bioactive Properties, Seconder Metabolites, Fatty Acids and Sensory Properties of Green Jalapeño Peppers. Processes, 12(10), 2291. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr12102291