Bridging Gaps in Holistic Rehabilitation After Critical Illness: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Physical wellness emphasizes the physiological aspects of health, including mobility, strength, and overall physical function. Early mobilization through passive and active exercises, respiratory therapy, and nutritional support is crucial to prevent complications such as muscle atrophy and pressure ulcers [13].

- Emotional wellness refers to the affective domain, encompassing the ability to recognize, express, and manage a full range of emotions, from anxiety and fear to hope and resilience. For ICU patients, this dimension is vital for processing the traumatic experience of critical illness. Providing emotional support through therapeutic communication, counseling, and family involvement helps patients navigate this distress [14].

- Psychological wellness is conceptualized here as a broader construct that includes both mental health and cognitive functioning. This integrated view is justified by the profound interplay in the ICU between a patient’s mental state (e.g., the presence of anxiety, depression, or delirium) and their cognitive capacities (e.g., attention, memory, executive function). Critical illness and the ICU environment can simultaneously impair both, making their combined consideration essential for a holistic recovery model. Interventions such as mental health support, delirium assessments, and orientation activities are therefore grouped under this dimension to promote overall psychological and cognitive recovery [15].

- Social wellness highlights the importance of relationships and social support networks in recovery. Interventions such as family involvement in care, communication facilitation, and participation in support groups (e.g., ICU Steps in the UK) strengthen social support systems [16].

- Spiritual wellness involves finding meaning and purpose in life, particularly significant for patients facing life-threatening conditions. Integrating spiritual care includes addressing patients’ spiritual needs, discussing values and beliefs, and offering access to chaplaincy services, meditation, or personal reflection [10,11].

- Environmental wellness considers how surroundings affect health and well-being, including the physical and emotional atmosphere of the ICU. Creating a healing environment by minimizing noise, ensuring privacy, optimizing lighting, and providing comfort measures enhances recovery and fosters a sense of safety [17].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Questions

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Definition of Variables

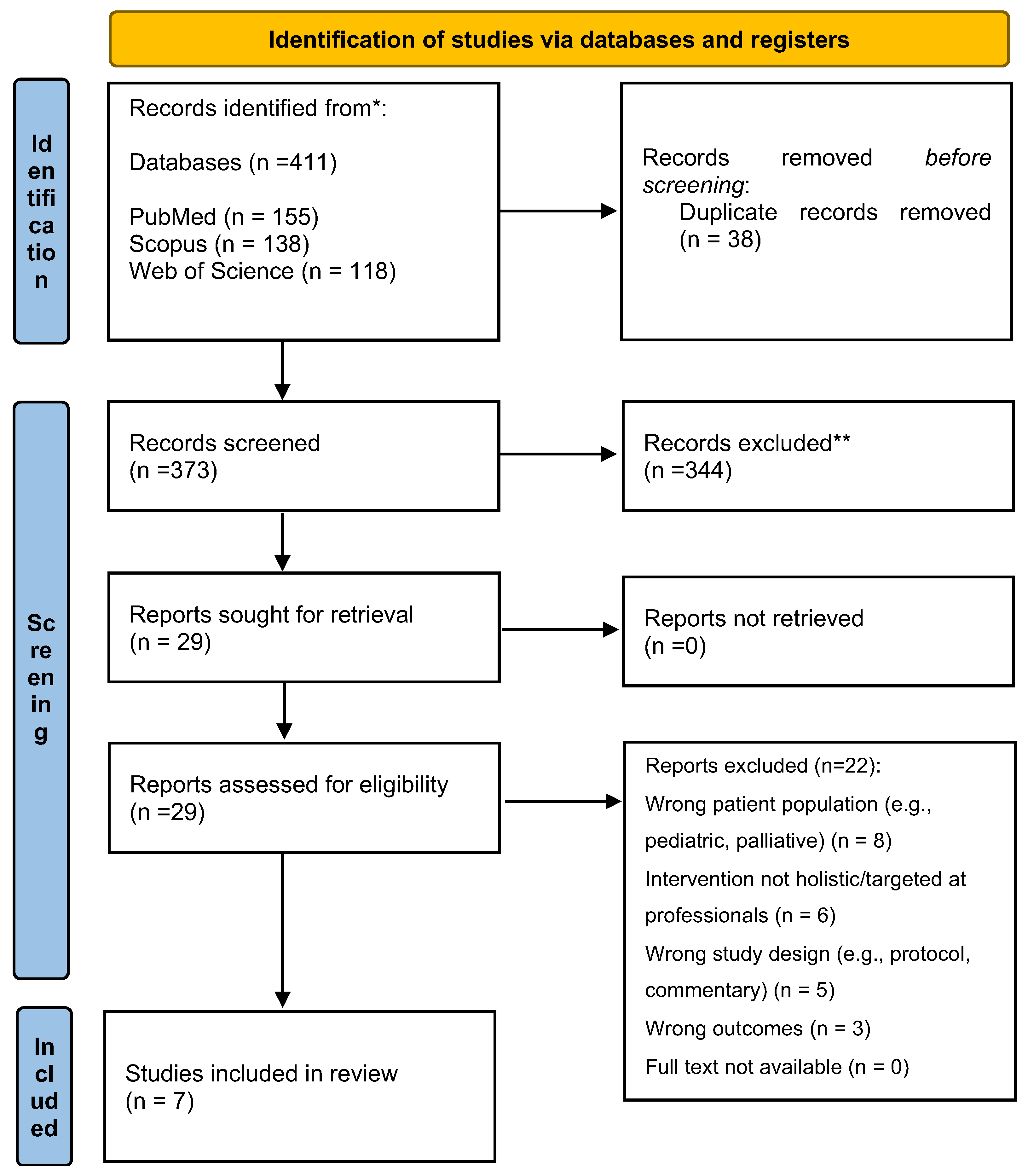

2.4. Search Methods

2.5. Methodological Quality Appraisal

2.6. Data Abstraction

2.7. Data Analysis

2.8. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Interventions for Physical Wellness

3.2. Interventions for Psychological and Emotional Wellness

3.3. Interventions for Spiritual Wellness

4. Discussion

Contribution to Education

5. Recommendations for Clinical Practice and Future Research

5.1. Recommendations for Nursing Practice

- Implement Structured Non-Pharmacological Interventions: Integrate evidence-based practices such as Corporeal Rehabilitation Care (CRC) sessions [26] or reflexology [29] into daily nursing care plans for anxious or agitated patients to reduce physiological stress and potentially decrease sedation requirements.

- Facilitate Family Integration: Adopt a structured approach to family involvement. Provide families with a simple guidebook on communicating with sedated patients and actively facilitate their participation in psychological care, as modeled by Black et al. [24].

- Provide Spiritual Care Resources: Utilize a readily available Spiritual Care Toolkit [27] containing multi-faith resources (e.g., sacred texts, meditation audio, prayer journals) to address spiritual distress. Nurses should receive basic training on how to introduce and use these resources sensitively.

- Initiate ICU Diaries: Lead the implementation of patient diaries within the ICU. Coordinate contributions from the healthcare team and family members to create a narrative that helps patients process their experience and fill memory gaps post-ICU [28].

5.2. Recommendations for Relatives and Family Members

- Engage in Guided Communication: Use provided guidance to talk to the patient about familiar topics, read to them, or play their favorite music, even if they appear non-responsive. This can provide comfort and psychological support [24].

- Participate in Diary Creation: Contribute to the patient’s ICU diary by writing simple entries about daily events, family news, or words of encouragement. This provides a crucial personal perspective for the patient to reflect on later [28].

- Collaborate with the Spiritual Care Team: Inform nurses about the patient’s spiritual or religious beliefs and preferences. Be open to using provided spiritual resources (e.g., reading a familiar prayer) to comfort the patient [29].

5.3. Recommendations for Assessing Patient Progress

- Physical Wellness: Use the Activity of Daily Living (ADL) scale and the Six-Minute Walk Test (6MWT) to quantitatively measure functional recovery and mobility [25].

- Psychological and Emotional Wellness: Utilize short, validated tools like the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [25] for mood or the Impact of Events Scale-Revised (IES-R) for post-traumatic stress symptoms to track psychological recovery.

- Spiritual Wellness: The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy—Spiritual Well-Being (FACIT-Sp) scale is a brief, validated instrument suitable for assessing spiritual well-being in clinical settings [30].

- Overall Progress: Simple 0–10 numeric rating scales (NRS) for patient-reported pain, stress, and well-being can be administered quickly before and after interventions like CRC to gauge immediate effect [26].

5.4. Directions for Future Research

Limitations of the Review

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ambushe, S.A.; Awoke, N.; Demissie, B.W. Holistic Nursing Care Practice and Associated Factors among Nurses in Public Hospitals of Wolaita Zone, South Ethiopia. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, U.; Vyas, K.; Papathanassoglou, E. Psychosocial Support Interventions for Adult Critically Ill Patients During the Acute Phase of Their ICU Stay: A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEvoy, L.; Duffy, A. Holistic Practice—A Concept Analysis. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2008, 8, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamanzadeh, V.; Jasemi, M.; Valizadeh, L.; Keogh, B.; Taleghani, F. Effective Factors in Providing Holistic Care: A Qualitative Study. Indian. J. Palliat. Care 2015, 21, 214–224. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, J.M.; Kentish-Barnes, N.; Jacques, T.; Wysocki, M.; Azoulay, E.; Metaxa, V. Improving the Intensive Care Experience from the Perspectives of Different Stakeholders. Crit. Care 2022, 26, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, A.; Pires, S.; Sá, E.; Gomes, I.; Alves, E.; Fonseca, C.; Coelho, A. A Cross-Sectional Study of the Perception of Individualized Nursing Care Among Nurses in Acute Medical and Perioperative Settings. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 3191–3205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, T.; Cao, L.; Ye, L.; Song, W. Early Mobilization for Critically Ill Patients. Respir. Care 2023, 68, 781–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaikh, M.; Wade, D.M.; King, L.; Mackay, L.; Symes, I.; Syeda, A.; Greenburgh, A.; Deng, J. Psychological Interventions for Patients with Delirium in Intensive Care: A Scoping Review Protocol. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0315832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olding, M.; McMillan, S.E.; Reeves, S.; Schmitt, M.H.; Puntillo, K.; Kitto, S. Patient and Family Involvement in Adult Critical and Intensive Care Settings: A Scoping Review. Health Expect. 2016, 19, 1183–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klimasiński, M.W. Spiritual Care in the Intensive Care Unit. Anaesthesiol. Intensive Ther. 2021, 53, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willemse, S.; Smeets, W.M.; van Leeuwen, E.M.; Heldens, J.; Napel-Roos, N.M.T.; Foudraine, N. Spiritual Care in the Intensive Care Unit: Experiences of Dutch Intensive Care Unit Patients and Relatives. Dimens. Crit. Care Nurs. 2023, 42, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strout, K.A.; Howard, E.P. The Six Dimensions of Wellness and Cognition in Aging Adults. J. Holist. Nurs. 2012, 30, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korompeli, A.; Karakike, E.; Galanis, P.; Myrianthefs, P. Pressure Ulcers and Nursing-Led Mobilization Protocols in ICU Patients: A Retrospective Observational Cohort Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prigerson, H.G.; Viola, M.; Brewin, C.R.; Cox, C.; Ouyang, D.; Rogers, M.; Pan, C.X.; Rabin, S.; Xu, J.; Vaughan, S.; et al. Enhancing & Mobilizing the Potential for Wellness & Emotional Resilience (EMPOWER) among Surrogate Decision-Makers of ICU Patients: Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. Trials 2019, 20, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papathanassoglou, E.D.E. Psychological Support and Outcomes for ICU Patients. Nurs. Crit. Care 2010, 15, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines, K.J.; Quasim, T.; McPeake, J. Family and Support Networks Following Critical Illness. Crit. Care Clin. 2018, 34, 609–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S. Effects of Healthcare Environmental Design on Medical Outcomes. In Design and Health: The Therapeutic Benefits of Design; Dilani, A., Ed.; Design and Health Publishers: Stockholm, Sweden, 1991; pp. 49–59. [Google Scholar]

- Velasco Bueno, J.M.; Heras La Calle, G. Humanizing Intensive Care: From Theory to Practice. Crit. Care Nurs. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 32, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvande, M.E.; Angel, S.; Højager Nielsen, A. Humanizing Intensive Care: A Scoping Review (HumanIC). Nurs. Ethics 2022, 29, 498–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, 2nd ed.; John Wiley and Sons: Chichester, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kohn, L.T.; Corrigan, J.M.; Donaldson, M.S. (Eds.) Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. In To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Needham, D.M.; Davidson, J.; Cohen, H.; Hopkins, R.O.; Weinert, C.; Wunsch, H.; Zawistowski, C.; Bemis-Dougherty, A.; Berney, S.C.; Bienvenu, O.J. Improving Long-Term Outcomes after Discharge from Intensive Care Unit: Report from a Stakeholders’ Conference. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 40, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, T.H.; Stone, J.C.; Sears, K.; Klugar, M.; Leonardi-Bee, J.; Tufanaru, C.; Aromataris, E.; Munn, Z. Revising the JBI quantitative critical appraisal tools to improve their applicability: An overview of methods and the development process. JBI Evid. Synth. 2023, 21, 478–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, P.; Shea, J.A.; Post, S.; Sullivan, K.M. The effect of nurse-facilitated family participation in the psychological care of the critically ill patient. J. Adv. Nurs. 2011, 67, 1091–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemyze, M.; Komorowski, M.; Mallat, J.; Arumadura, C.; Pauquet, P.; Kos, A.; Granier, M.; Grosbois, J.M. Early intensive physical rehabilitation combined with a protocolized decannulation process in tracheostomized survivors from severe COVID-19 pneumonia with chronic critical illness. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgeon-Ghittori, S.; Douplat, M.; Lejus-Bourdeau, C.; Peigneux, H.; Venel, M.; Richard, J.C.; Bonnet, A.; Leconte, M.; Touzet, S.; Tadié, J.M. Corporeal rehabilitation care in ICU patients: Effects on stress, pain, and well-being. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kincheloe, R.L.; Schafer, D.; Meyer, R.; Foster, B.; DiMarco, D. A Spiritual Care Toolkit: An evidence-based solution to meet spiritual needs. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, 1612–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pattison, N.; O’Gara, G.; Lucas, C.; Cole, L. Filling the gaps: A mixed-methods study exploring the use of patient diaries in the critical care unit. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2019, 51, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korhan, E.A.; Yönt, G.H.; Khorshid, L. The effect of holistic nursing interventions on intensive care patients’ comfort and anxiety. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2014, 30, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulut, H.; Akın, B.; Duru, P.; Demirel, M. Effects of holistic nursing interventions on intensive care patients: A randomized controlled study. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2023, 74, 103370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secunda, K.E.; Kruser, J.M. Patient-Centered and Family-Centered Care in the Intensive Care Unit. Clin. Chest Med. 2022, 43, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.P.; Tsai, Y.F. Maintaining patients’ dignity during clinical care: A qualitative interview study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2011, 67, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eklind, S.; Olby, K.; Åkerman, E. The intensive care unit diary—A significant complement in the recovery after intensive care: A focus group study. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2023, 74, 103337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, B.B.; Luz, M.; Rios, M.N.d.O.; Lopes, A.A.; Gusmao-Flores, D. The impact of intensive care unit diaries on patients’ and relatives’ outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Care 2019, 23, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F. Cohort Study on Medical-Integrated Holistic Nursing’s Impact on Intensive Care Unit Patients’ Outcomes, Complications, and Comprehensive Health Care. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirakhmi, I.N.; Purnawan, I. Effectiveness of Structured Spiritual Care Models in Improving Psychological and Physiological Outcomes in Intensive Care Unit (ICU) Patients: A Systematic Review. J. Health Nutr. Res. 2025, 4, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roze des Ordons, A.L.; Stelfox, H.T.; Sinuff, T.; Grindrod-Millar, K.; Sinclair, S. Exploring spiritual health practitioners’ roles and activities in critical care contexts. J. Health Care Chaplain. 2022, 28, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bone, N.; Swinton, M.; Hoad, N.; Toledo, F.; Cook, D. Critical care nurses’ experiences with spiritual care: The SPIRIT study. Am. J. Crit. Care 2018, 27, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veloso Costa, A.; Padfield, O.; Elliott, S.; Hayden, P. Improving patient diary use in intensive care: A quality improvement report. J. Intensive Care Soc. 2021, 22, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIlroy, P.A.; King, R.S.; Garrouste-Orgeas, M.; Tabah, A.; Ramanan, M. The effect of ICU diaries on psychological outcomes and quality of life of survivors of critical illness and their relatives: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 47, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullman, A.J.; Aitken, L.M.; Rattray, J.; Kenardy, J.; Le Brocque, R.; MacGillivray, S.; Hull, A.M. Diaries for recovery from critical illness. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 12, CD010468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; Bäckman, C.; Capuzzo, M.; Egerod, I.; Flaatten, H.; Granja, C.; Rylander, C.; Griffiths, R.D.; RACHEL Group. Intensive care diaries reduce new onset post traumatic stress disorder following critical illness: A randomised, controlled trial. Crit. Care 2010, 14, R168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, R.E.; Tarrier, N. Evaluation of the effect of prospective patient diaries on emotional well-being in intensive care unit survivors: A randomized controlled trial. Crit. Care Med. 2009, 37, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Focus | Conceptual Question | Features |

|---|---|---|

| Setting (S) | Where is it? | Inclusion: Critical care settings (e.g., intensive care unit, critical care unit); Exclusion: Pediatric ICUs, coronary care units, general wards, end-of-life care. |

| Perspective (P) | Who is affected? | Inclusion: Critically ill adult patients (>18 years) admitted to critical care units. Exclusion: Pediatric patients, cardiovascular patients, palliative/terminally ill patients. |

| Intervention (I) | What is the intervention? | Inclusion: Interventions related to holistic care (physical, emotional, psychological, social, spiritual, environmental). Exclusion: Interventions targeted at healthcare professionals. |

| Comparison (C) | What is compared? | Standard nursing care. |

| Evaluation (E) | What outcomes? | Patient outcomes relating to the six dimensions of wellness within holistic care. |

| Database | Boolean Search Strategy |

|---|---|

| PubMed | (“ICU” OR “intensive care” OR “critical care”) AND (“holistic nursing care” OR “holistic nursing practice” OR “holistic nursing care practice” OR holistic *) AND (patient outcome OR outcome * OR physical * OR emotional * OR psychological * OR spiritual * OR social * OR environmental *) |

| Scopus | (“holistic AND nursing AND care” OR “holistic AND nursing AND practice” OR “holistic AND nursing AND care AND practice” OR holistic *) |

| Web of Science | (“ICU” OR “intensive care” OR “critical care”) AND (“holistic nursing care” OR “holistic nursing practice” OR “holistic nursing care practice” OR holistic *) AND (patient outcome OR outcome * OR physical * OR emotional * OR psychological * OR spiritual * OR social * OR environmental *) |

| Author (Year) Country | Study Design | Population and Setting | Intervention | Primary Wellness Dimension(s) | Key Outcomes Measured | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bourgeon-Ghittori et al. (2022) France | Observational |

| Corporeal Rehabilitation Care (CRC): Multi-sensory, esthetic care sessions delivered by socio-estheticians. | Physical, Emotional |

|

|

| Black et al. (2011) UK | Quasi-experimental (Comparative time series) |

| Structured Family Involvement: Nurses facilitated family participation using a guidance booklet for psychological care. | Psychological, Social |

|

|

| Kincheloe et al. (2018) USA | Quasi-experimental |

| Spiritual Care Toolkit: Provided multi-faith resources (books, music, journals) to patients, families, and nurses. | Spiritual |

|

|

| Lemyze et al. (2022) France | Retrospective single-center |

| Early Intensive Rehabilitation: Combined physical rehab with a structured decannulation protocol. | Physical, Psychological |

|

|

| Pattison et al. (2019) UK | Mixed-methods |

| Patient Diaries: Diaries maintained by staff/family during ICU stay and given to patients post-discharge. | Psychological, Emotional |

|

|

| Korhan et al. (2014) Turkey | Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) |

| Reflexology: 30 min sessions (foot, hand, ear) twice daily for 5 days. | Physical, Emotional |

|

|

| Bulut et al. (2023) Turkey | Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) |

| Structured Spiritual Care: 8 sessions based on the T.R.U.S.T. model over 4 weeks. | Spiritual |

|

|

| Author (Year) | Study Design | JBI Checklist | Total Score | Summary of Appraisal & Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bourgeon-Ghittori et al. (2022) [26] | Observational | Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies | 6/8 | Moderate quality. Strengths: Clearly defined criteria, standardized measurement. Key limitations: The lack of a control group significantly limits the ability to attribute outcomes solely to the intervention, as confounding factors and natural recovery cannot be ruled out. |

| Black et al. (2011) [24] | Quasi-Experimental | Checklist for Quasi-Experimental Studies | 7/9 | Moderate quality. Strengths: Clearly defined groups, complete follow-up. Key limitations: The non-randomized allocation of participants introduces a high risk of selection bias, weakening causal inferences. Blinding was not used. |

| Kincheloe et al. (2018) [27] | Quasi-Experimental | Checklist for Quasi-Experimental Studies | 6/9 | Moderate quality. Strengths: Multiple outcome measurements from different perspectives. Key limitations: The absence of a control group makes it difficult to assess the toolkit’s effect compared to standard care. No blinding or allocation concealment was implemented. |

| Lemyze et al. (2022) [25] | Case Series | Checklist for Case Series | 6/10 | Low to moderate quality. Strengths: Complete participant inclusion for the cohort, clear reporting of demographics. Key limitations: As a single-arm case series with no comparator, the design is highly susceptible to bias and confounding. Outcomes were not independently assessed. |

| Pattison et al. (2019) [28] | Mixed-Methods | Checklist for Mixed Methods Research | 7/8 (Qual) 7/8 (Quan) | Good quality. Strengths: Methodological components are well-integrated to address the research question, and both qualitative and quantitative elements scored well. Key limitations: The study does not explicitly state how divergences between qualitative and quantitative findings were addressed. |

| Korhan et al. (2014) [29] | Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) | Checklist for RCTs | 8/13 | Moderate quality. Strengths: Randomization was used, and groups were similar at baseline. Key limitations: The high risk of performance bias as participants and therapists were not blinded. Detection bias is also a concern as the outcome assessor was not blinded. |

| Bulut et al. (2023) [30] | Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) | Checklist for RCTs | 9/13 | Good quality. Strengths: Proper randomization, complete follow-up, and reliable outcome assessment. Key limitations: The lack of blinding of participants and therapists (performance bias) is a notable limitation, as expectations could influence the results of interventions like spiritual care. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Korompeli, A.; Kydonaki, K.; Myrianthefs, P. Bridging Gaps in Holistic Rehabilitation After Critical Illness: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2324. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182324

Korompeli A, Kydonaki K, Myrianthefs P. Bridging Gaps in Holistic Rehabilitation After Critical Illness: A Systematic Review. Healthcare. 2025; 13(18):2324. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182324

Chicago/Turabian StyleKorompeli, Anna, Kalliopi Kydonaki, and Pavlos Myrianthefs. 2025. "Bridging Gaps in Holistic Rehabilitation After Critical Illness: A Systematic Review" Healthcare 13, no. 18: 2324. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182324

APA StyleKorompeli, A., Kydonaki, K., & Myrianthefs, P. (2025). Bridging Gaps in Holistic Rehabilitation After Critical Illness: A Systematic Review. Healthcare, 13(18), 2324. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182324