1. Introduction

Since service-oriented intelligent robots are developed to realize intelligent interaction with people, such as hotel service robots, medical service robots and so on, all of these robots need to perform their tasks quickly in a human–robot collaborative environment. At the same time, robotic systems developed with existing technologies should strictly prevent unintended physical contact—including collisions and blockages—during human–robot interaction, as these hazardous events may cause unpredictable harm, especially to vulnerable populations such as the elderly, children and persons with disabilities. Thus, the capability to accurately and rapidly detect individuals, groups and crowd densities becomes crucial when robots perform operational tasks. This perceptual capacity not only optimizes navigation routes and ensures efficient task completion, but also represents one of the most challenging research frontiers in robotics. Furthermore, these advancements in computer vision-based pedestrian detection and analysis capabilities could be applied across multiple domains, including human–robot interaction [

1], video surveillance [

2], intelligent transportation systems [

3], etc.

Recently, plenty of algorithms and network frameworks for automatic identification and localization of pedestrians from images or videos have been published [

4], which can be broadly categorized into two aspects [

5]: (i) two-stage detection methods based on candidate frames represented by R-CNN [

6] and Faster-RCNN [

7]; and (ii) single-stage detection methods represented by YOLO [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12] and SSD [

13]. The two-stage detection approach could be described as follows: Firstly, potential regions of interest are explicitly generated within the input image. Subsequently, each candidate region is resized to fixed dimensions based on its image characteristics. These regions then undergo feature extraction through a pre-trained convolutional neural network (CNN) model [

14], followed by both final classification and regression operations to achieve the desired detection objectives. This method is slow, although the detection accuracy is high. Subsequently, a single-stage detection method has been proposed. It does not need to pre-calculate the pre-selected regions. Instead, it employs deep neural networks to extract features directly from input images. Then, the extracted feature maps are directly utilized to perform simultaneous object classification and coordinate regression for target localization. Finally, the expected test results are obtained. Nowadays, it serves as the mainstream approach in some modern detection technology fields [

15]. It significantly helps to improve processing speed while maintaining optimal performance, particularly in small object detection scenarios. However, it still has limitations: various uncertainty factors occur during detection. This behavior fails to capture the complete feature representation of targets and leads to compromised accuracy, manifesting as both false positives and missed detections. These uncertainty factors mainly come from two aspects: (i) Visible regions with small-scale features often fall below the algorithm’s detection threshold; (ii) Occluded targets are frequently overlooked during detection [

16].

For example, Fang et al. [

17] proposed integrating the concept of receiving field attention into the Conv and C2f modules, introducing a self-designed four-layer adaptive spatial feature fusion module and a small target dynamic head structure (DyHead-S) to improve the performance of pedestrian detection in dense scenarios. Dou et al. [

18] proposed introducing a multi-scale feature fusion module and an improved non-maximum suppression (NMS) algorithm based on the YOLOv8 model to enhance the effectiveness and the superiority of the model. Peng et al. [

19] proposed FedsNet, a pedestrian detection network based on RT-DETR. They constructed a lightweight backbone ResFastNet to reduce parameters/computation for faster speed, integrated EMA with the backbone for a new ResBlock to improve small target detection, adopted DySample as up-sampling to boost accuracy/robustness and used SIoU as loss to enhance accuracy and speed convergence. Liu et al. [

20] proposed to explicitly model the semantic context through context-aware pedestrian detection with self-supervision of visual language semantics and used a self-supervised prototype semantic contrast (PSC) learning method based on the more explicit semantic context obtained from VLS. Li et al. [

21] proposed integrating the receptive field attention into the convolution module, partially replacing the C2f module in the backbone network with the MobileViTv3 module, adding a TinyHead for detecting very small objects to the original detection head structure and adopting the boundary box regression loss function power-iouv2 to reduce false detections and missed detections. Ni et al. [

22] proposed an improved object detection method based on the SSD framework. The improved ResNet50 network was used to enhance information transmission. The indoor scene context was extracted through the multi-scale Context Information Extraction (MCIE) module and the indoor occlusion problem was solved with the help of the improved double-threshold non-maximum suppression algorithm (DT-NMS). Liu et al. [

23] proposed using MobileViT as the lightweight backbone to reduce parameters, designing an SCNeck-neck network for lossless feature fusion and adopting DEHead for multi-scale target detection. Liu et al. [

24] proposed the YOLOv8-CB lightweight multi-scale pedestrian detection algorithm, introducing the CFNet cascaded fusion network and the CBAM concern module to optimize the multi-scale feature semantics and location information representation, superimpose the BIFPN structure to fuse effective features and improve the performance of pedestrian detection.

To sum up, existing pedestrian detection algorithms have made certain progress. For example, the RMTP-YOLO model focuses on the detection of very small targets (e.g., distant pedestrians) and multi-scale feature capture. However, it has obvious shortcomings in terms of robustness in severely occluded scenarios, adaptability to low-light environments and detection performance in extremely dense scenarios. The YOLOv8-CB model focuses on lightweight deployment in in-vehicle scenarios and basic multi-scale fusion. Nevertheless, it has significant deficiencies in the detection accuracy of severely occluded pedestrians, the capture of distant small targets and cross-scenario generalization ability. Thus, existing pedestrian detection algorithms still face several challenges: Pedestrians exhibit diverse poses such as standing and walking, and when their features resemble the background, they are prone to false positives or false negatives. Pedestrians often occlude each other or are partially obscured by vehicles, buildings, etc., making it difficult for models to extract complete features and affecting detection reliability. Variations in the distance between pedestrians and the camera cause significant differences in target size, making small targets easy to overlook while large targets demand higher requirements for feature extraction and resource allocation. Addressing these gaps is critical, as unreliable detection directly compromises robot safety and operational efficiency.

To tackle these intertwined challenges, a novel dense pedestrian detection framework was proposed and named as Dense Pedestrian Detection Network based on YOLOv8n (DPDN-YOLOv8). Firstly, to enhance multi-scale pedestrian feature perception capabilities and address occlusion and background interference issues, the last three C2f modules in the YOLOv8n backbone were replaced with C2f_ODConv modules with Omni-Dimensional Convolutional layers. Through four-dimensional attention weight learning, introduced C2f_ODConv modules capture more comprehensive pedestrian contextual features. Secondly, to reduce information loss during up-sampling and preserve the semantic details of small targets, the original Up-Sample module is replaced with the Content-Aware Reassembly of Features up-sampling operator. Through the method of “dynamic kernel prediction + feature reassembly”, the quality of neck feature extraction and fusion was improved. Simultaneously, to improve the detection accuracy of small-scale pedestrians, reduce missed detections and false detections in occluded and low-light environments and enhance the model’s adaptive matching ability for pedestrians of different scales, a secondary innovation based on the original three detection heads of ASFF was presented via adding one dedicated detection head for small targets. Then, the four-detection-head ASFF-4 module was used to dynamically learn feature fusion weights, which reduces missed detections and false detections. Finally, to accelerate the network convergence speed, improve the bounding box regression accuracy of low-IoU hard samples and optimize the model’s ability to handle complex samples, the Focaler-IoU and Shape-IoU were integrated into the model to amplify the loss of low-IoU samples and constrain the localization and shape consistency of predicted boxes.

3. Proposed DPDN-YOLOv8 Model

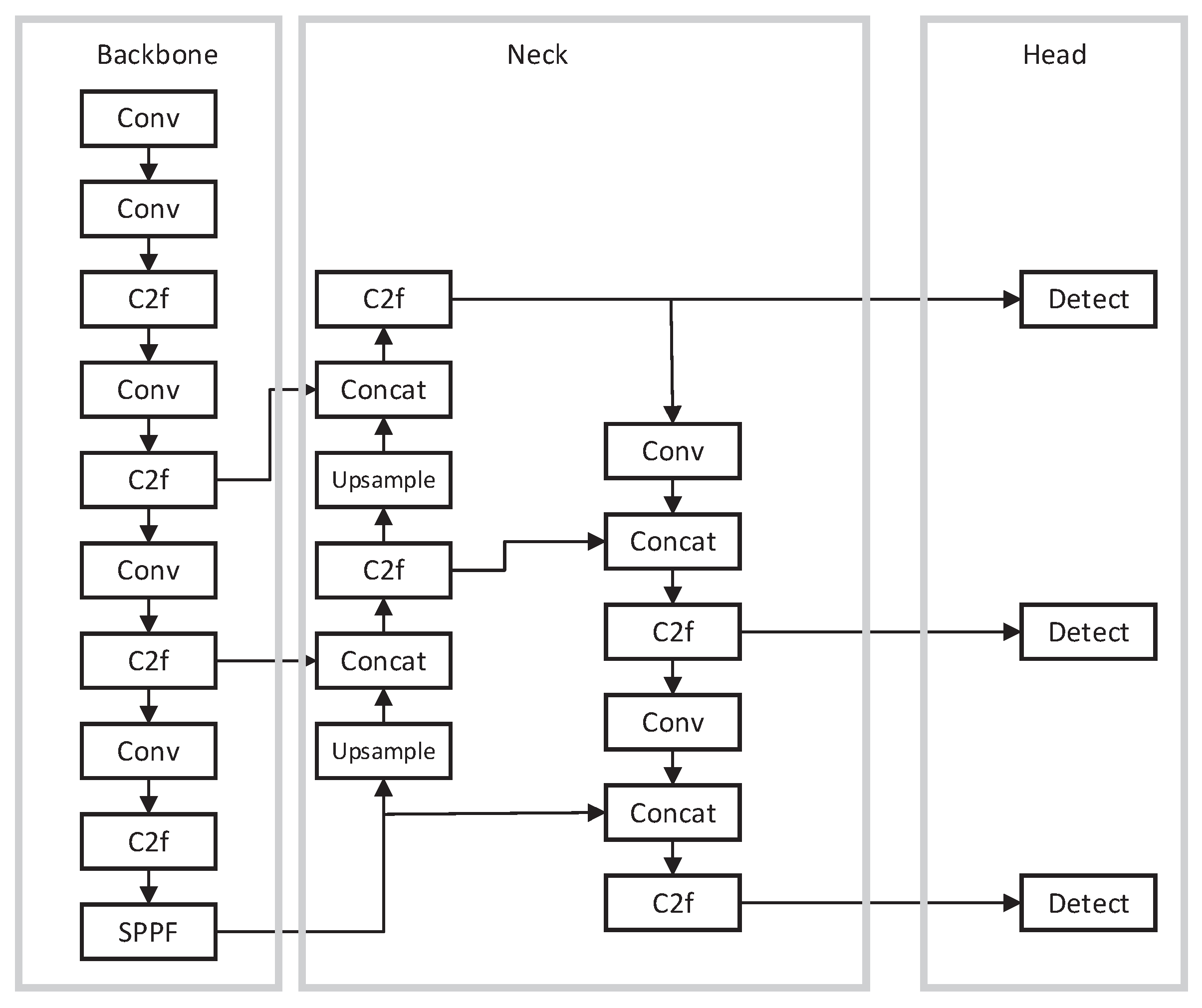

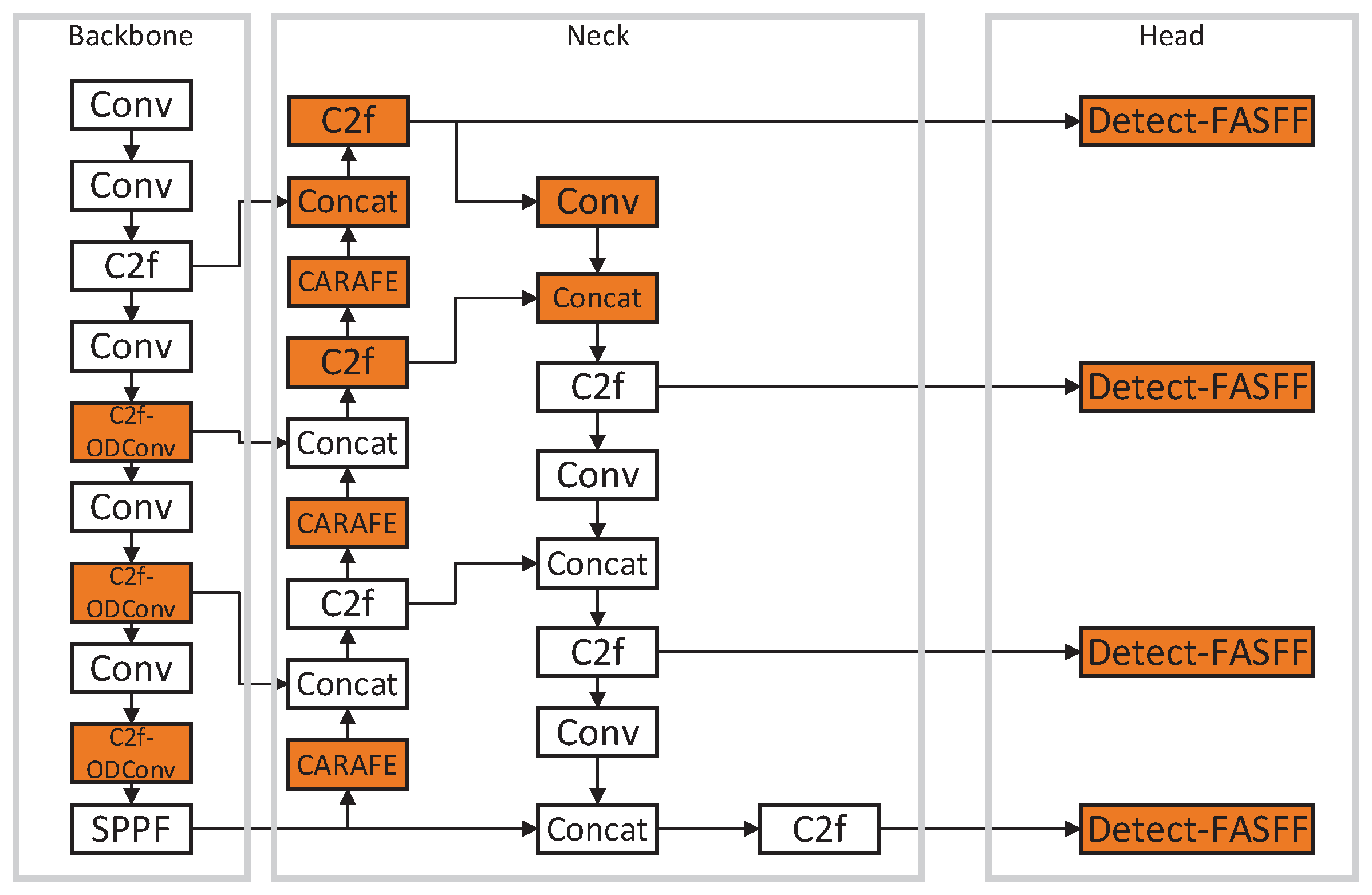

To enhance detection accuracy while reducing both missed detections and false alarms, an improved model based on the YOLOv8 network architecture was proposed and named as DPDN-YOLOv8. The network structure is illustrated in

Figure 2. The orange sections indicate the improved modules. Firstly, to enhance the network’s target perception capability during feature extraction, we propose the C2f_ODConv module, which replaces the last three C2f modules in YOLOv8’s backbone network. To ensure accurate feature extraction across multi-scale input data while meeting the diverse feature requirements for dense pedestrians in complex environments, the model enhances its cross-scale perception and feature extraction capabilities for pedestrian global contextual information. Consequently, the network can carry out accurate feature extraction for different input data characteristics. This, in turn, meets the diversified dense pedestrian environments and enhances the model’s ability of multi-scale perception and characterization of the pedestrians’ global contextual information. Secondly, the original sampling operator is replaced by the CARAFE up-sampling operator, which exhibits a broader receptive field. This architectural substitution enables the model to leverage semantic information from feature maps, thereby enhancing the neck network’s capability in both feature extraction and fusion. Simultaneously, we replace the detection head with the Adaptive Spatial Feature Fusion detector head with ASFF-4 module, which facilitates adaptive weight learning for spatial feature fusion to address cross-scale discrepancies, ultimately improving detection accuracy. Finally, the Focaler-Shape-IoU is employed as the loss function for bounding box regression. This advanced loss function is designed to address three key aspects: (1) minimizing the influence of low-quality samples on anchor box regression, (2) accelerating model convergence rate and (3) significantly improving detection precision for small-scale targets.

3.1. Omni-Dimensional Dynamic Convolution

In general convolution operations, convolutional layers primarily serve to enhance model performance. Existing approaches, such as adding new layers or stacking existing ones, inevitably increase computational demands and adversely affect detection efficiency. To address this, we integrate ODConv [

29] into the C2f module, presenting the novel C2f_ODConv module. This enhanced module enables parallel learning of convolutional kernel features across four dimensions of the kernel space; consequently, it captures more comprehensive contextual information and diverse feature representations, thereby significantly improving detection accuracy. Moreover, this approach achieves enhanced precision in target detection.

Next, the details of the ODConv module are discussed. It employs an advanced multi-attention mechanism with parallel processing strategy to simultaneously capture attention across four dimensions of the convolutional kernel space: (i) kernel spatial size, (ii) input channels, (iii) output channels and (iv) kernel count. This architecture subsequently utilizes the attention-weighted convolutional kernels to achieve high-precision recognition of complex features in dense pedestrian scenarios.

where,

denotes the feature dimension of the output channels, while

represents the spatial dimensions (H × W) of the feature map. The input channel feature dimension is characterized by

, whereas its spatial extent is defined by a size of H × W.

represents the kernel-wise (

) attention mechanism;

stands for the spatial attention mechanism over the k×k convolutional kernel space; and both

and

represent the input-channel and output-channel attention mechanisms, respectively.

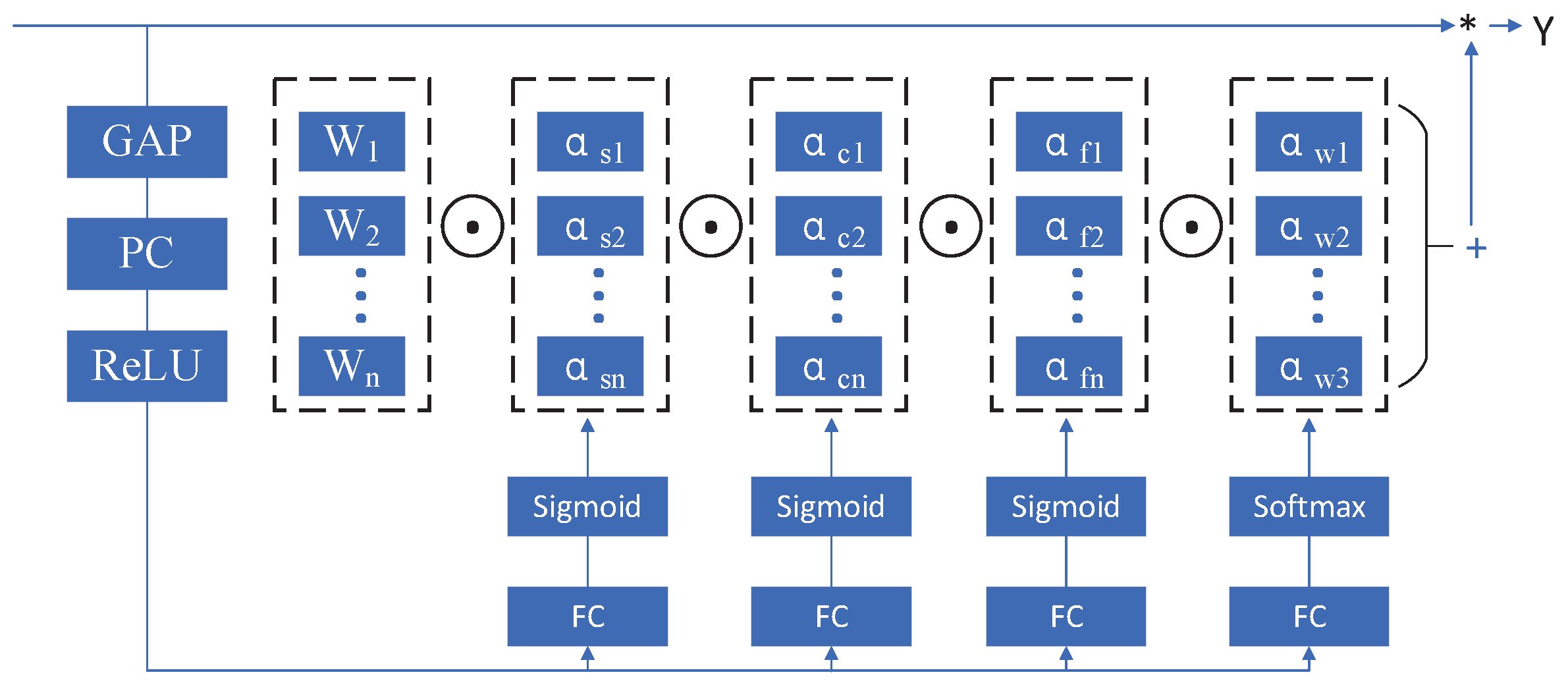

The omni-dimensional dynamic convolution structure is illustrated in

Figure 3. The input feature X is compressed into a feature vector through Global Average Pooling (GAP). Subsequently, this vector is mapped to a low-dimensional space via a Fully Connected (FC) layer, with negative values being zeroed out by the ReLU activation function. Finally, the processed feature vector is distributed to four parallel computational branches. The four branches, each processed through a fully connected (FC) layer followed by a Sigmoid activation function, enable the initial three branches to capture attention to scalars for three key convolutional kernel attributes: spatial dimensions, input channels and output channels, respectively. The final branch derives attention to scalars along the kernel’s channel-count dimension. Finally, the attention scalars from all four dimensions are convolved with the input features X to generate the output features Y.

3.2. CARAFE Up-Sampling Operator

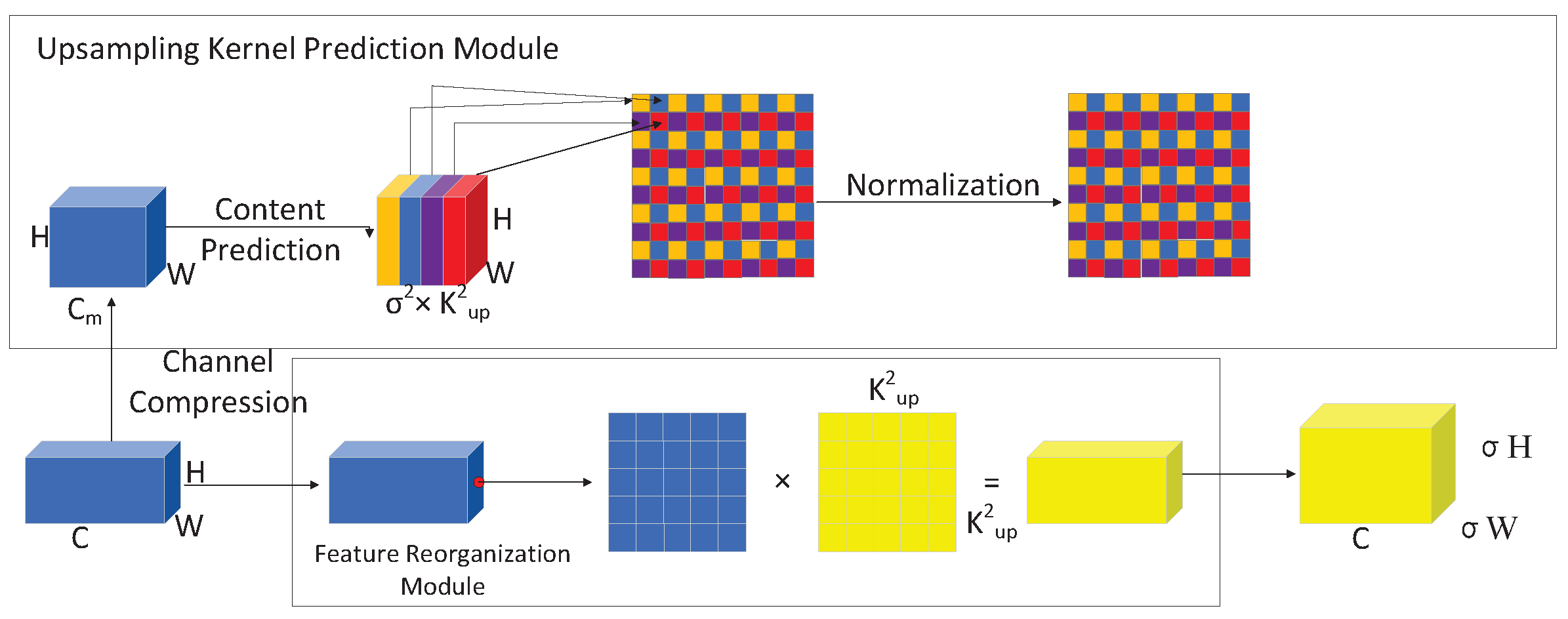

The incorporation of the CARAFE [

30] up-sampling operator into the neck network represents the second innovation of this study. In the complex scenario of pedestrian detection, the foundational model exhibits deficiencies in semantic information and insufficient size of sensory regions during the super-resolution process. These deficiencies lead to suboptimal feature fusion performance. To address this issue, the original up-sampling operator in the YOLOv8 baseline model was replaced with the CARAFE up-sampling operator. The architecture of the new network is illustrated in

Figure 4. As shown in

Figure 4, the diagram visually presents the CARAFE network architecture, with the upper section illustrating the Up-Sampling Kernel Prediction Module (showing the process from feature compression to kernel normalization) and the lower section depicting the Feature Reorganization Module (demonstrating how input features are mapped and recombined).

The CARAFE up-sampling operator consists of a kernel prediction module and a feature reassembly module. In the kernel prediction module, the input feature map has dimensions of , where C represents the number of channels, while H and W denote the height and width of the feature map, respectively. In the initial stage, the feature map undergoes convolutional compression to a specified channel dimension to reduce computational requirements. Subsequently, content prediction yields an up-sampling kernel with dimensions . This is followed by normalization to obtain convolution kernels with weights summing to 1, ensuring the feature map’s magnitude remains unaffected. Within the feature reassembly module, information from the output feature map is mapped back to the input feature map. A region centered at is then extracted and subjected to dot product operations with the up-sampling kernel, ultimately producing an output feature map with dimensions .

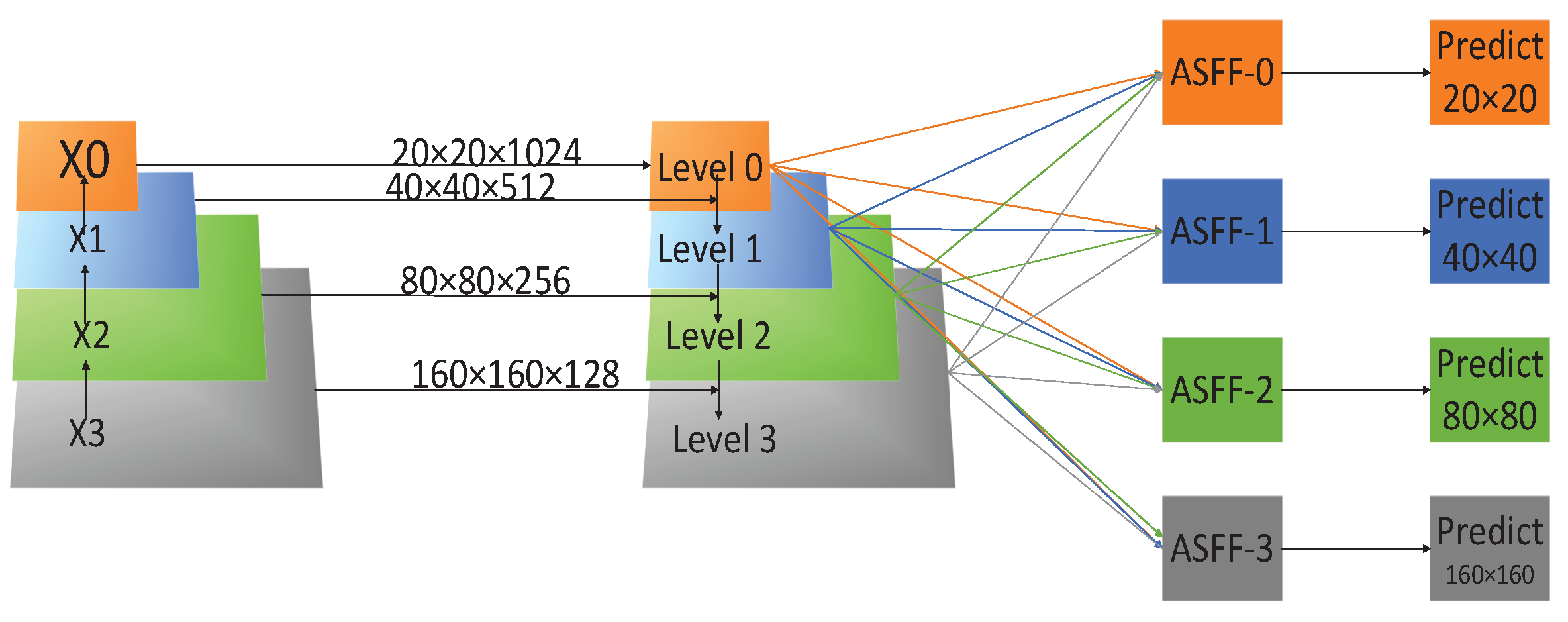

3.3. ASFF-4 Detection Heads

The introduction of the ASFF-4 module to YOLOv8’s detection head constitutes the third innovation. In the YOLOv8 object detection algorithm, the Head module is primarily responsible for final object detection and bounding box prediction. It employs a Detect structure as its Head module, which has demonstrated strong detection performance across numerous specific scenarios. However, in scenarios involving complex tasks such as occluded or overlapping pedestrian detection, it faces significant challenges. This is primarily attributed to the diversity in pedestrian feature scales, substantial feature variations and overlapping annotation regions, all of which contribute to suboptimal detection outcomes. Under such circumstances, certain objects may obstruct the neck network from extracting critical feature information, resulting in target information loss. This fundamentally explains the persistently high false alarm rate observed in pedestrian detection systems.

To solve the above problems, the improved structure based on ASFF [

31] was introduced, which adds a novel detection head structure named ASFF-4 to the baseline three-head detection architecture of ASFF. The newly added small-object detection head is designed to achieve secondary extraction of small targets. This structural design achieves three key improvements: one is to enhance multi-scale object detection capability for pedestrian recognition, the second is extraction of more profound hierarchical features leading to notable accuracy gains, and the third is effective mitigation of feature degradation in multi-scale fusion processes.

The process of calculating the ASFF-4 detection head is shown in Equation (

2):

where the term is used to denote the fusion features generated on layer l that are ultimately employed for prediction. refers to the input value of the feature vector at (x, y) in the n-th layer feature map prior to the fusion of features on layer l. The term signifies the learnable weight parameters of the feature maps of four distinct levels up to the lth layer. These parameters correspond to the weight parameters of the feature maps of Level 0, Level 1, Level 2 and Level 3, which are obtained through back-propagation convolution of 1 × 1 during the training process. The feature maps are obtained through 1 × 1 back-propagation convolution during the training phase. The values of the control weight parameters are constrained to the interval [0, 1] and the sum of is normalized to 1. The main schematic structure of the ASFF-4 module is shown in

Figure 5 below.

As shown in the figure, it presents the structure of the ASFF-4 module, which enables adaptive spatial feature fusion for multi-scale pedestrian detection. On the left side, the feature maps are processed to generate hierarchical feature levels — Level 3 preserves fine-grained details for small or occluded pedestrians, while Level 0 captures global contextual information for large or long-distance targets. Subsequently, four ASFF modules take these multi-level features as inputs and each module adaptively learns feature weights and optimal fusion ratios based on spatial positions and target sizes to resolve the inconsistency of cross-scale features. Finally, the fused features from each ASFF module are fed into prediction heads with matching resolutions, thereby achieving accurate detection of pedestrians at different scales, enhancing the model’s multi-scale information integration capability, reducing missed detections and false detections and thus improving the robustness of dense pedestrian detection.

The demonstrated ASFF-4 module adaptively adjusts feature weights to ensure the model autonomously selects the most effective features across different spatial locations, thus preventing inadequate feature representation. Moreover, it dynamically assigns optimal fusion ratios based on actual scenarios and target sizes to minimize both missed detections and false alarms.

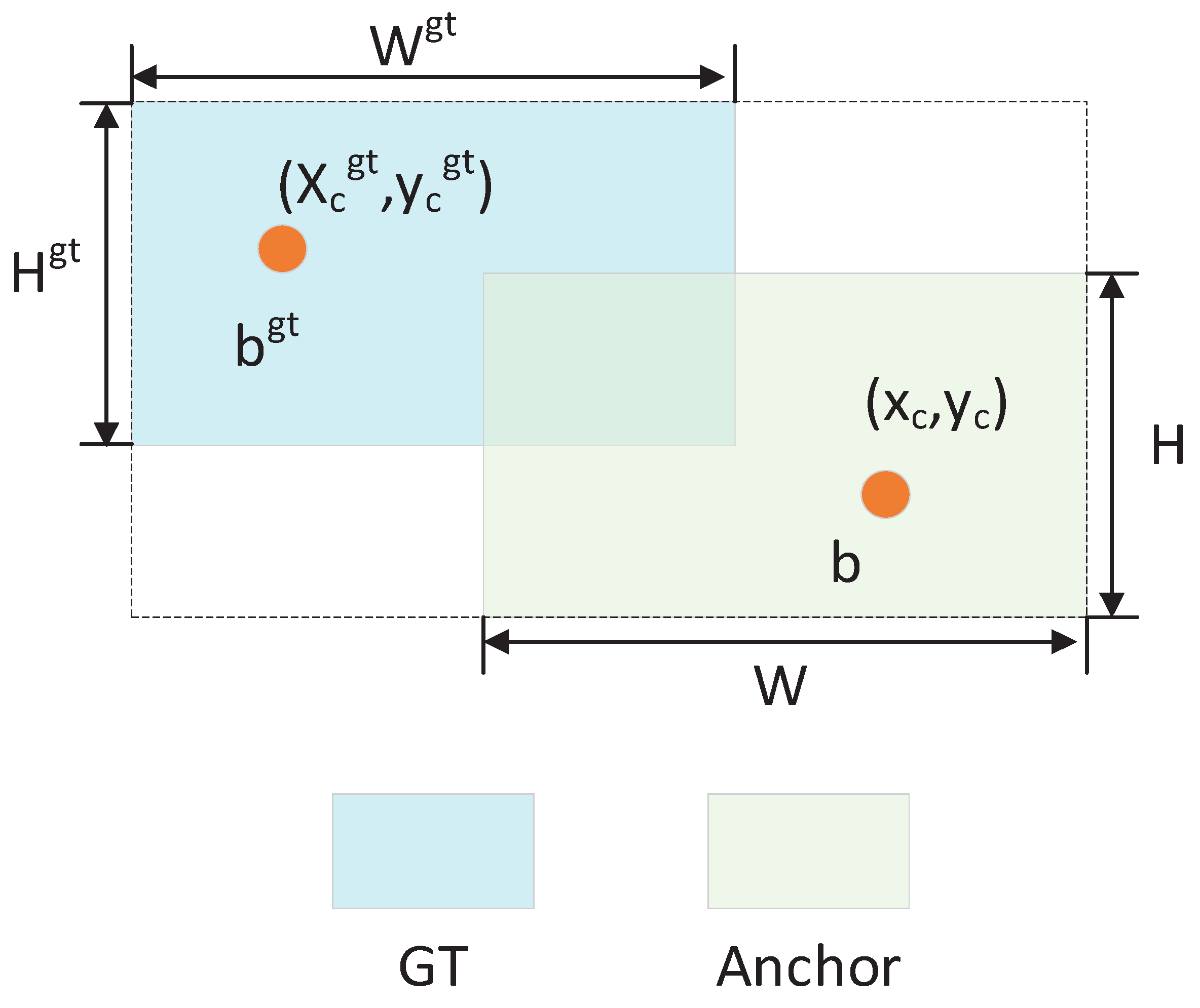

3.4. Loss Function

The YOLOv8n architecture initially employs CIoU loss [

32] for bounding box prediction, which accounts for both overlap area and aspect ratio differences. However, its inability to adaptively weight samples based on detection difficulty results in the aspects of delayed optimization convergence, compromised model generalization and ultimately constrained detection performance enhancement. Therefore, the insights from Focaler-IoU [

33] and Shape-IoU [

34] were incorporated to propose an enhanced loss function. The implementation is illustrated in

Figure 6.

Focaler-IoU focuses on low-IoU challenging samples (e.g., occluded or small-scale pedestrians) by amplifying the loss contribution of hard-to-detect samples via focal weighting, while simultaneously constraining spatial localization accuracy. Shape-IoU achieves “object shape and scale matching” by imposing shape penalty terms to constrain the consistency between bounding boxes and the actual shape and scale of pedestrians. The specific formulas are as follows:

The traditional intersection-to-parallel ratio IoU is defined as

where B denotes the prediction frame, while

signifies the real frame. IoU is a metric that quantifies the degree of overlap between the prediction frame and the real frame. As demonstrated, higher IoU values correspond to greater prediction accuracy. In dense pedestrian detection scenarios, failure to adequately account for sample difficulty and bounding box shape/size characteristics may adversely affect regression performance.

In order to achieve the defined objectives, two learnable parameters (dd and uu) were employed into the Focaler-IoU module. One is to increase the loss weight of low IoU samples. The other is designed to enhance the model’s focus on small objects and low-overlap samples; the details are elaborated as follows:

is a penalty term for the center point distance between the predicted bounding box and the ground-truth bounding box, constraining the accuracy of spatial localization.

where

and

are the coordinates of the center of the prediction box;

and

are the coordinates of the center of the real box; and

c is the diagonal length of the minimum circumscribed rectangle that contains the prediction box and the true box.

and

are the weight coefficients calculated based on the target aspect ratio. The calculation formula for the weight coefficient is as follows:

where

and

are the width and height of the real frame, respectively, and

is the scaling factor related to the size of the target in the dataset. Additionally,

is a shape loss term that adjusts the discrepancy between width and height through learnable weighting factors, formulated as

where both

and

could be thought of as the shape loss factors between width and height, respectively. Their calculation formulas could be described as follows:

Finally, by combining the Focaler-IoU loss function with the Shape-IoU loss function, to maintain sensitivity for challenging samples, the core components

and

of Focaler-IoU are directly retained. Shape-IoU is introduced to impose shape/scale constraints, incorporating

into the loss function with a weighting coefficient of 0.5 for the shape penalty term. The Focaler-Shape-IoU loss function could be obtained as follows:

In summary, within pedestrian detection scenarios—where targets are predominantly distributed in dense, non-uniform clusters—the Focal-Shape-IoU method achieves superior performance. Firstly, it adaptively tunes sampling focus through a linear-interval mapping mechanism. Also, it precisely optimizes shape and scale features for complex samples. Secondly, the dual approach enhances accuracy and recognition reliability, demonstrating measurable improvements in both precision and robustness.

4. Results

To verify the effectiveness of the DPDN-YOLOv8 model, we conducted both ablation studies and comparative experiments. These experiments systematically evaluated the feasibility and applicability of the proposed network.

4.1. Experimental Environment

In this subsection, to experimentally validate the effectiveness of the proposed network, the model was trained for 300 epochs using a batch size of 8, the stochastic gradient descent (SGD) optimizer and images of size

. The weight decay factor was set to 0.0005, the initial learning rate to 0.01 and the learning rate momentum factor to 0.937. Detailed experimental environment configurations are presented in

Table 1.

4.2. Dataset

A series of experiments were conducted using the CrowdHuman [

35] dataset. The dataset comprises 15,000 images in the training set, 5000 images in the test set and 4370 images in the validation set, totaling 24,370 images. It contains approximately 470,000 annotated instances, with each image averaging 23 individuals and exhibiting various occlusions.

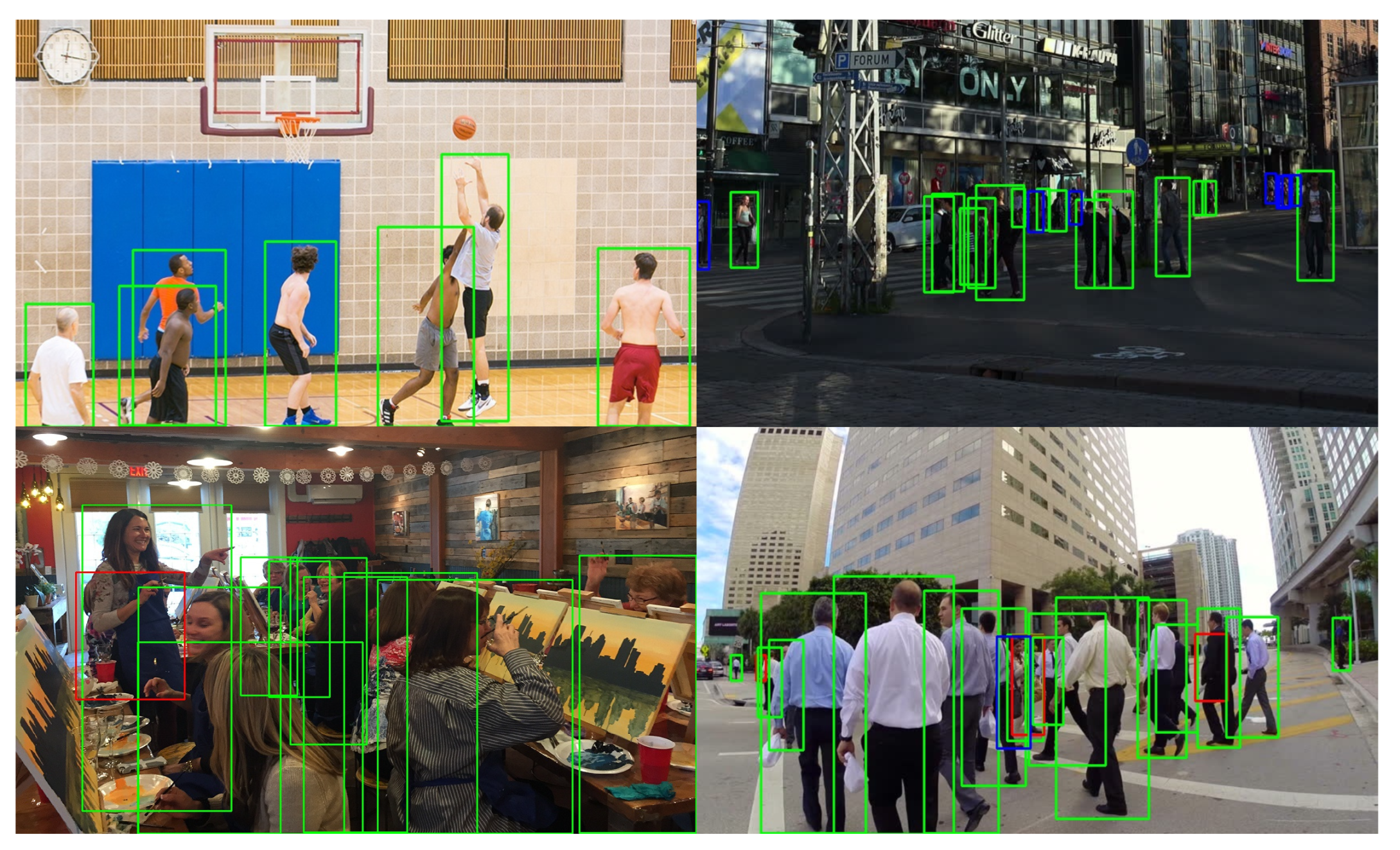

These images cover various existing dense crowd scenarios in complex environments. Although each pedestrian instance is annotated as either head, visible body parts or full body, only full-body labels were adopted for the focus of this study. Some of the images in the dataset and their annotations are shown in

Figure 7.

4.3. Assessment of Indicators

This experiment evaluates model performance using six metrics: (P), (R), mAP@50, mAP@50:95, model size and floating-point operations per second (GFLOPs).

measures the proportion of instances predicted as positive samples by the model that are actually positive. It reflects the accuracy of the model in predicting positive samples.

can be calculated by the following equation:

where

denotes true positive and

denotes false positive.

The recall rate is a metric that measures a model’s ability to correctly predict all positive samples, also known as the total inspection rate. Its calculation formula is as follows:

where

denotes false negatives and

denotes true positives.

The

score is a measure of the harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a comprehensive evaluation of these two metrics. A higher

F1 score indicates better performance in both precision and recall. The formula for calculating the

F1 score is

mAP50 refers to the mean average precision of the model’s predictions when IoU (Intersection over Union) is no less than 0.5. This metric is commonly used for benchmarking. mAP50-95 refers to calculating AP (Average Precision) when IoU is in the range of [0.5, 0.95] at intervals of 0.05 and then averaging the obtained AP values.

GFLOPs: a commonly used metric to reflect the computational complexity of a model. If GFLOPs are too high, it may restrict the deployment and operational efficiency of the model on devices with limited computing power.

4.4. Ablation Experiments

To verify the effectiveness of various improvements in DPDN-YOLOv8, ablation experiments were conducted on the CrowdHuman dataset to comprehensively analyze the performance differences of different improvement methods. Using YOLOv8n as the baseline model, a series of experiments were progressively enhanced for the C2f module in the backbone, up-sampling operator, detection head and loss function via a series of experiments, demonstrating the impact of each module on model performance. The “√” indicates the application of corresponding improvement methods to the YOLOv8n network model. The experimental results are shown in

Table 2.

From

Table 2, in Experiment 2, based on the YOLOv8 foundation model, the last three C2f modules in the backbone network were replaced with C2f_ODConv. This modification resulted in respective improvements of 0.3%, 0.4%, 1.7% and 1.9% in P, R, mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 metrics. The results demonstrate that the feature extraction capability of the novel model could be enhanced via C2f_ODConv module to make sure more effective processing of occlusions and interfering features have been obtained in dense pedestrian detection tasks.

In Experiment 3, the traditional up-sampling operator is also replaced by the CARAFE up-sampling operator, which could improve the quality of the up-sampled feature maps via their semantic information and enhance the ability of the necking network to extract and fuse image features. Compared with the original model, the improvements were 0.9%, 1.1%, 2.3% and 2.7% in P, R, mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95, respectively. Thus, the effectiveness of the replaced up-sampling operator has been validated.

In Experiment 4, the introduction of the ASFF-4 detection head enabled the model to learn adaptive spatial fusion weights at different spatial locations. This enhancement improved both the localization accuracy and feature extraction capability for heavily occluded targets and ensured more precise object localization. As shown in

Table 2, the improved algorithm achieved significant gains of 1.1%, 3.6%, 4% and 5.1% in P, R, mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 metrics, respectively. These results demonstrate that the modified component can adaptively integrate pedestrian features from different network levels; thus, the accuracy has been enhanced.

In Experiment 5, the improved Focaler-Shape-IoU loss function was adopted as the bounding box regression function. Compared with the baseline algorithm, all evaluation metrics showed improvements, enhancing the network’s detection accuracy. Then, the results demonstrate that further optimization of the loss function can significantly enhance the overall performance of the improved network, with respective improvements of 0.9%, 1%, 2.3% and 2.5% observed in P, R, mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 metrics. These findings indicate that the Focaler-Shape-IoU loss function could effectively improve the capability to handle complex samples.

As shown in

Table 2, Experiments 6, 7 and 8, incorporating multiple improvements, demonstrate significant enhancements in P, R, mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 compared to Experiment 1. Then, Experiment 9 combines the first three improvements, achieving respective increases of 0.9%, 4.2%, 4.3% and 5.5% in these metrics relative to Experiment 1. Moreover, Experiment 10 integrates all proposed enhancements. Notably, the mAP@0.5 value reaches 85.6%, representing a 5.1% gain over the original algorithm, with other metrics showing commensurate improvements. The comprehensive analysis of the ablation study results indicates that despite an increase in parameters, our approach achieved optimal performance across all key metrics: the F1 score,

and

all reached the highest values in this ablation experiment. The above description indicates that the improved algorithm strikes a favorable balance between model complexity and detection accuracy, validating its superiority in overall performance.

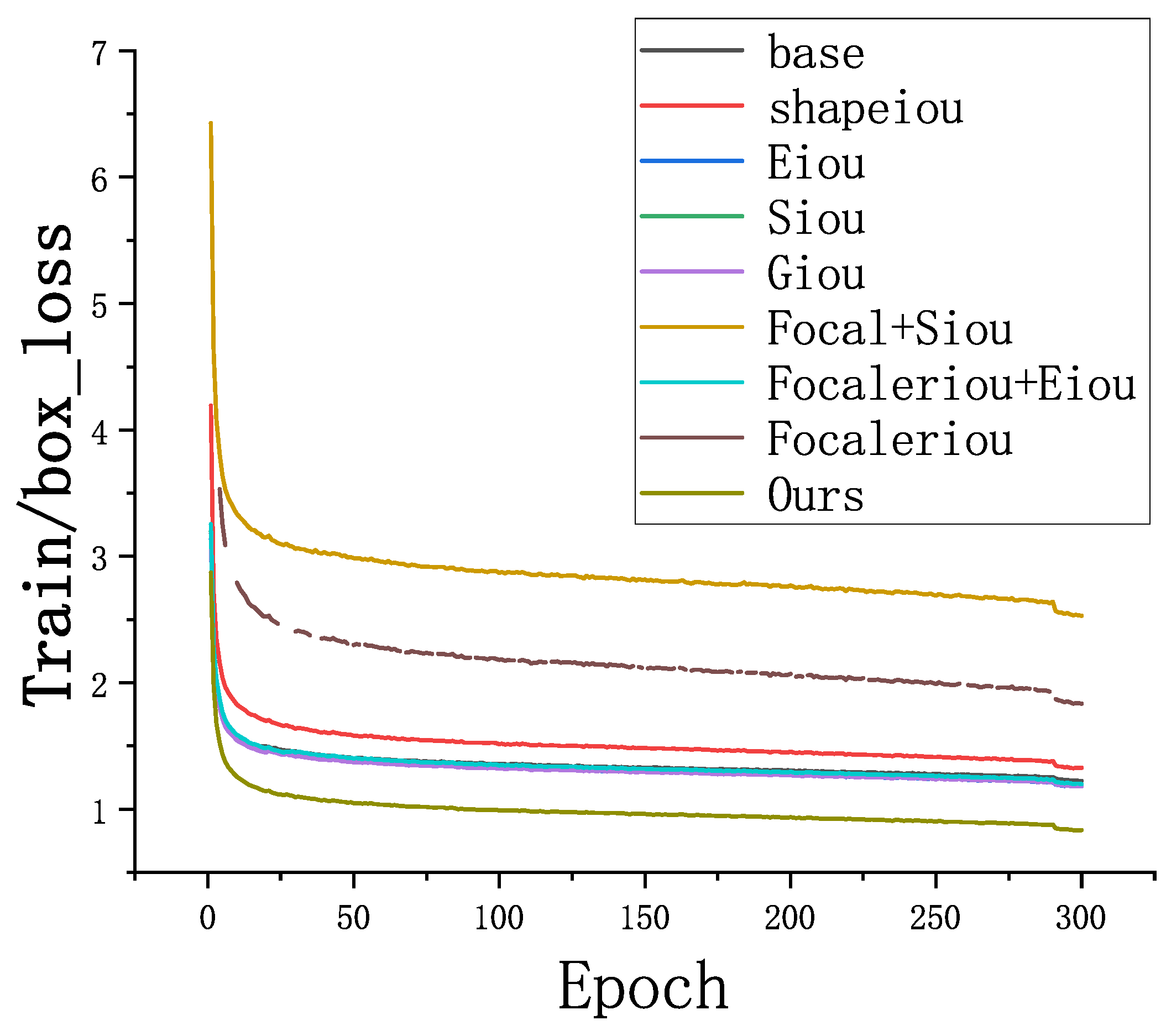

4.5. Loss Function Comparison Experiment

A comparative analysis with existing methods(e.g., EIou [

36], SIou [

37], GIou [

38], FocalerioU, ShapeioU, Focal-SIou [

39] and Focaler-EIou [

40] was conducted to determine the most suitable loss function and verify the effectiveness of Focaler-Shape-IoU. The experimental results in

Table 3 demonstrate that Focaler-Shape-IoU emerges as the most effective approach, which has achieved improvements of 1.3% in mAP@0.5 and 0.9% in Precision. These findings further validate the superiority of the proposed loss function over the baseline CIoU loss function. Meanwhile, the visualization results (see

Figure 8) more intuitively show that the curve corresponding to Focaler-Shape-IoU has a faster decreasing speed of bounding box loss during the training process; also, with the increase in the number of training epochs, in the later stage of training the loss value is significantly lower than that of other compared loss functions. As is well known, the lower the bounding box loss, the higher the accuracy of the model’s prediction for the target bounding box. From the perspective of gradient stability, Focaler-Shape-IoU effectively avoids the issues of gradient explosion and vanishing by optimizing the mathematical form of the loss function, thereby ensuring smoother gradient updates during the training process. In terms of sample difficulty modeling, a dynamic sample difficulty perception mechanism is introduced. It can accurately distinguish the difficulty and ease levels of samples, assigning higher loss weights to deal with the difficult samples and enhance the model’s ability for the learn objects in complex scenarios. Therefore,

Figure 8 intuitively verifies that Focaler-Shape-IoU could more effectively optimize bounding box regression performance during training, fully demonstrating its advantages over other loss functions.

4.6. Comparative Experiments of Different Algorithms

Here, we conduct a comprehensive comparison between our proposed network (DPDN-YOLOv8) and other state-of-the-art object detection models, including two-stage algorithms (e.g., Faster R-CNN), single-stage YOLO series (SSD, RetinaNet [

41], RTDETR, SOLIDER, YOLOv5 [

42], YOLOv7 [

43], YOLOv10 [

44], YOLOv11 [

45]), and the baseline YOLOv8n model. The experimental results are systematically presented in

Table 4.

The experimental results demonstrate that the proposed network achieves an mAP@0.5 of 85.6%, representing a 5.1% improvement over the baseline YOLOv8n model. Furthermore, comparative analysis reveals its significant advantages in both parameter efficiency and detection accuracy when benchmarked against other state-of-the-art networks.

The comparative analysis with other YOLO variants demonstrates that DPDN-YOLOv8 achieves significant performance improvements, observed as follows:

(i) 5.8% (mAP@0.5) and 8.6% (mAP@0.5:0.95) over YOLOv5;

(ii) 3.6% (mAP@0.5) and 5.7% (mAP@0.5:0.95) versus YOLOv7-tiny, with an additional parameter reduction;

(iii) 5.6% (mAP@0.5) and 4.9% (mAP@0.5:0.95) compared to YOLOv10;

(iv) 5.4% (mAP@0.5) and 6.2% (mAP@0.5:0.95) against YOLOv11.

To sum up, the key accuracy metrics of DPDN-YOLOv8—specifically mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5-0.95—achieve the highest values among all compared models, demonstrating significant advantages over classical two-stage models and RetinaNet. Compared with the baseline models in the YOLO series, the proposed algorithm also demonstrates a remarkably significant improvement in accuracy. In terms of model size, DPDN-YOLOv8 has parameters, which can be regarded as characteristic of a lightweight model. This is because its size is significantly smaller than other models, such as RTDETR and SOLIDER. Meanwhile, its accuracy far surpasses that of smaller lightweight models like YOLOv5. In terms of computational complexity, its GFLOPS is 15.7, balancing accuracy with reasonable computational speed while remaining far below SOLIDER and RTDETR. The parameter count and computational cost of DPDN-YOLOv8 are both within the manageable range of mobile devices, and its accuracy far surpasses that of other models. Therefore, even with a relatively large number of parameters, this method can still be successfully deployed on mobile devices.

To validate the statistical reliability of the performance improvements, key metrics across multiple replicate experiments were analyzed: an independent samples t-test compared metric differences between DPDN-YOLOv8 and the baseline model YOLOv8n, while one-way ANOVA assessed performance variations between DPDN-YOLOv8 and models such as YOLOv5, YOLOv7-tiny and RTDETR. Results indicate that DPDN-YOLOv8 exhibits statistically significant differences from comparison models across key metrics, confirming that the performance gains are not random fluctuations but rather effective contributions from the proposed method.

4.7. Generalization Experiment

To validate the generalization capability of the DPDN-YOLOv8 algorithm, this section conducts comparative experiments on the Cityperson dataset. It comprises 5000 images captured by vehicle-mounted cameras across 27 European cities. The images are divided into training (2975 images), validation (500 images) and test (1575 images) sets. Each image contains an average of 7 people, featuring various small-scale objects and occlusions. Annotations include visible regions and full-body regions. The experimental results are shown in

Table 5:

As shown in

Table 5’s comparative experiments on the Cityperson dataset, DPDP-YOLOv8 achieves significantly improved detection accuracy compared to YOLOv8n, indicating superior pedestrian detection performance. Simultaneously, the model’s parameter count increased from

to

and FLOPs rose from 8.1 to 15.7, reflecting a moderate growth in computational complexity. Despite this increase, the model parameters remain suitable for deployment in mobile object detection applications.

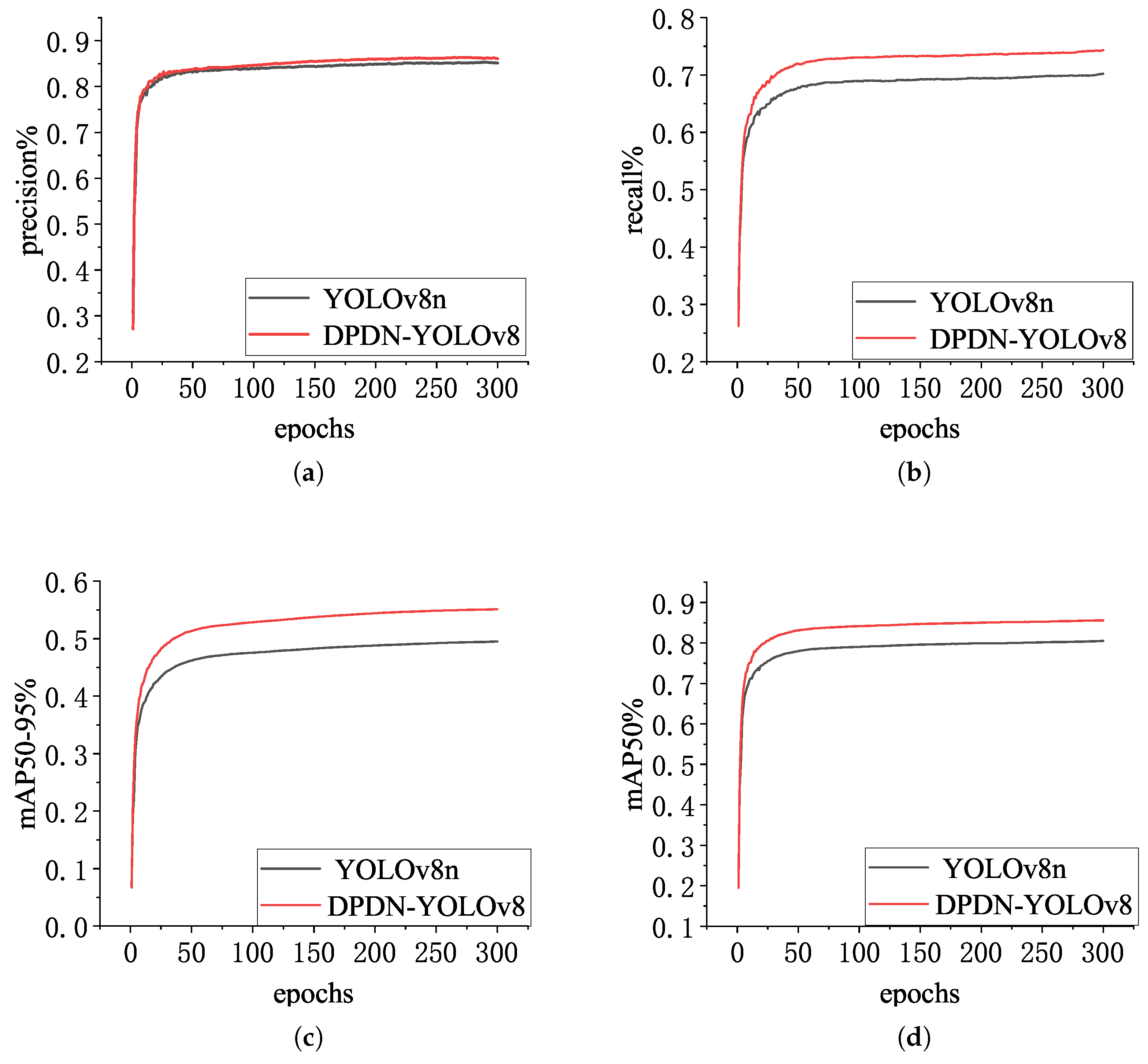

4.8. Visualization Results

To further validate the performance of the DPDN-YOLOv8 model, both YOLOv8n and DPDN-YOLOv8 models were trained on the CrowdHuman dataset. A comparative analysis was conducted on the training results, evaluating four key metrics: precision, recall, mean Average Precision at IoU = 0.5 (mAP@0.5) and mean Average Precision over IoU thresholds from 0.5 to 0.95 (mAP@0.5:0.95).

Figure 9 provides visual representations that offer more intuitive comparisons of these metrics. Thus, the proposed algorithm consistently outperformed the baseline model.

Figure 9 presents the comparison results between YOLOv8 and DPDN-YOLOv8 in four core detection metrics: precision, recall, mAP@0.5:0.95 and mAP@0.5, clearly illustrating the performance evolution and differences between them during the training process. In terms of precision, as the number of training iterations increases, two models rise rapidly and converge—with DPDN-YOLOv8’s accuracy consistently remaining higher than that of YOLOv8n—and eventually stabilize above 85%. This indicates that the improved model exerts stricter control over the correctness of detection results and generates fewer false positives. In terms of Recall, two models exhibit an upward convergence trend. Then, the proposed DPDN-YOLOv8 demonstrates a significantly higher recall than the other model, eventually stabilizing above 75%. This indicates that it can more effectively capture real pedestrian targets while maintaining a significantly lower missed detection rate. In terms of mAP@0.5:0.95, the proposed model outperforms YOLOv8n throughout the entire training process, eventually stabilizing above 55%. Moreover, as training progresses, the gap between them gradually widens. Therefore, it proves that the proposed model possesses stronger robustness and significantly enhances fine-grained localization capability under varying localization precision requirements. On the mAP@0.5 curve, DPDN-YOLOv8 outperforms YOLOv8n significantly, eventually stabilizing above 85%. This further validates its advantages in fundamental detection capabilities. Overall, DPDN-YOLOv8 consistently and comprehensively surpasses the benchmark model YOLOv8n across four key metrics. These results indicate that the proposed method effectively enhances the model’s detection performance for dense pedestrians, reduces missed detections and false positives, and boosts robustness in scenarios with varying localization precision requirements.

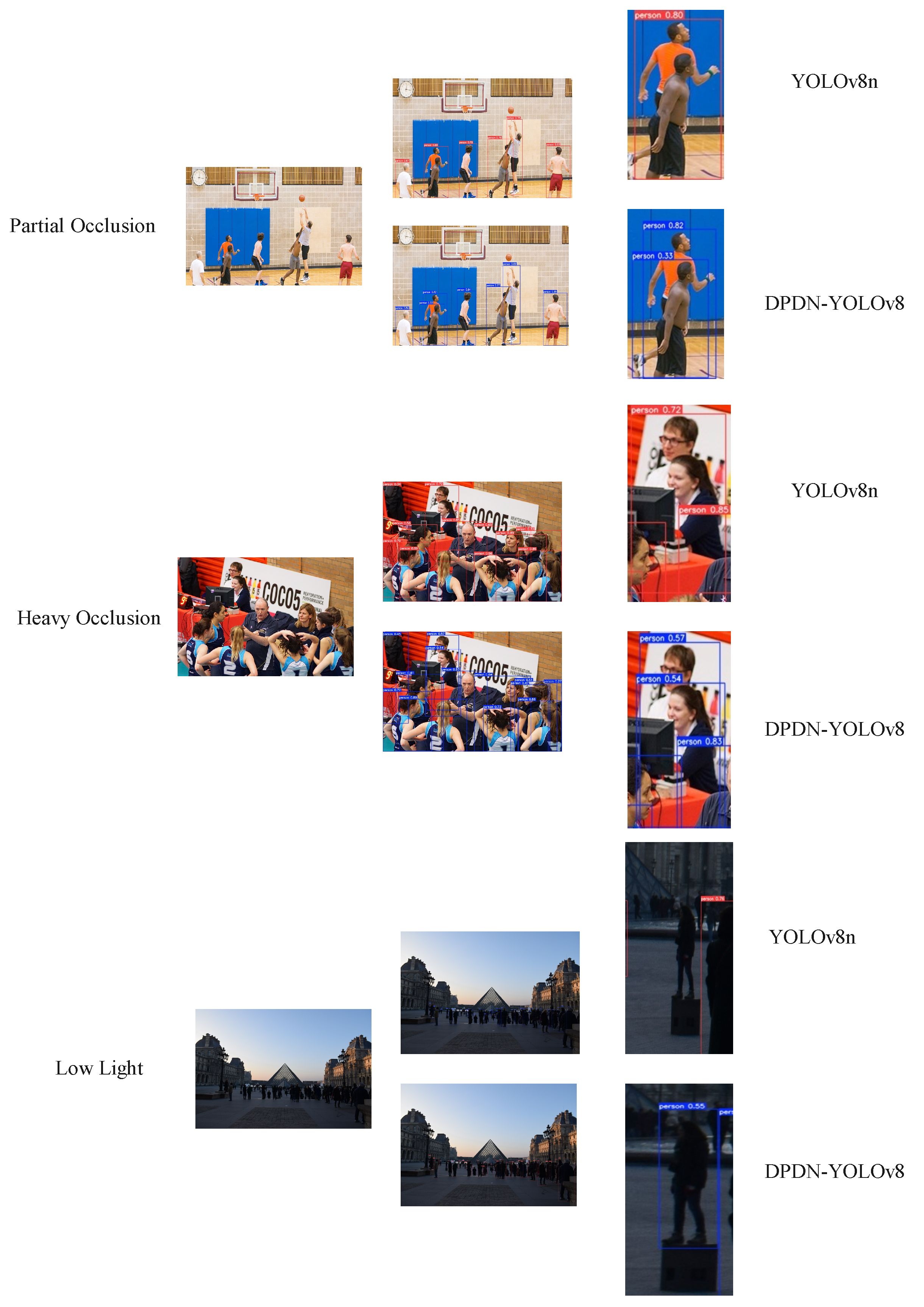

To visually demonstrate the detection performance of DPDN-YOLOv8 in complex scenarios, we selected three challenging scenarios—partial occlusion, severe occlusion and low-light conditions—and conducted comparative visualization experiments between YOLOv8n and DPDN-YOLOv8. The results are shown in

Figure 10. The detection results of YOLOv8n and DPDN-YOLOv8 in three challenging scenarios are compared: partial occlusion, heavy occlusion and low light. In partial occlusion, DPDN-YOLOv8 can more accurately detect occluded targets with precise bounding boxes and high confidence. For heavy occlusion, it outperforms YOLOv8n by effectively identifying pedestrians with only partial features exposed, reducing missed detections. In low-light environments, DPDN-YOLOv8 also demonstrates strong adaptability, stably detecting pedestrians with reliable bounding boxes and confidence scores. Overall, DPDN-YOLOv8 exhibits excellent advantages: superior occlusion resistance, strong adaptability to low-light conditions and higher detection accuracy and confidence, making it more robust in complex scenarios.

Figure 11 presents a visual comparison between the DPDN-YOLOv8 model and the original dataset annotations across various challenging scenarios, including motion scenes, urban streets, crowded indoor environments and outdoor pedestrian flows. Green bounding boxes indicate correctly detected targets, blue boxes represent missed detections and red boxes denote false positives. It can be observed that DPDN-YOLOv8 effectively detects the majority of pedestrian targets in complex scenarios involving partial occlusion, severe crowding and complex lighting conditions. This demonstrates the enhanced robustness of the improved model in accurately identifying and localizing pedestrian targets under various challenging conditions.