1. Introduction

Global institutional implementation of online learning is no longer an area dominated by “early adopters”, and as such all educators now face the common pressure of effectively adapting their current teaching ideologies and practice to converge with rapidly expanding digital tools and expectations for learning and teaching [

1]. They must also negate the complexities surrounding the current disruptive and unstable climates of online education and institutional economic security [

2]. Administrators of institutions are increasingly aware of trying to find effective strategies for motivating this “next wave” adoption of online learning and teaching [

3]. Although research supports the implementation of constructivist and learner-centred pedagogy for online learning success [

4], many educators cite difficulties in adapting their current traditional teaching methods to these theoretically complex approaches [

5]. The purpose of this research is to seek to analyse a particular learning design methodology known as E-tivities [

6], with an interest in exploring these strategies in comparison to the Community of Inquiry (CoI) design framework [

7], as a commonly cited and recommended constructivist design theory. This research therefore explores whether E-tivities (and its associated constructs of e-Moderation and the 5-Stage Model) has the potential to provide a clear learning design framework for Social, Teaching and Cognitive Presence factors in the CoI framework. It also seeks to conceptualise the “how”, by drawing on the experience and expertise of practitioners currently using these Salmon design strategies “E-tivities” [

6] are based on constructivist and social learning principles, and are cited as a learning design methodology that is neither wholly daunting, or overly arduous [

8]. The issue is that although there is some research into the outcomes of applying these particular designing strategies [

9,

10,

11,

12], very little research or literature is available regarding practical design advice or how-to’s for implementing these strategies. Further, there is no research reviewing the connection between E-tivities and CoI with clear designing insights and strategies. This is relevant because the CoI approach has theoretically being successful for designing online learning to meet student satisfaction and, more importantly, retention in online learning [

13,

14]. However, the research available on using CoI for e-learning design often does not provide clear designing strategies and examples with first-hand experience from diverse learning designers. This research will focus on recent online blog posts that explore learning designers’ and educators’ experience and recommendations in designing successful online learning using E-tivities. The “bloggers” are not only individuals who have employed E-tivities in their online learning and teaching design for a substantial portion of their educating careers. They are also some of the most successful learning designers and educational experts on the topic of online learning around world today.

1.1. Research Proposal

The objective of this research is explore if the online learning design strategies of E-tivities, and subsequent associations of e-Moderation and the 5-Stage Model, may provide a clear methodology for applying the CoI theoretical framework in designing online learning. From a case study approach, this research will explore the participant blog data for designing themes and exemplars for Social, Cognitive and Teaching presence strategies.

The overarching research proposal is:

How might E-tivities, e-Moderation and the 5-Stage Model be applicable and designed to cater to Social, Cognitive, and Teaching Presence categories of the Community of Inquiry framework?

Therefore the main research questions being investigated are:

Are there key principle advice given for designing E-tivities in general that might be useful for future online educators?

How might E-tivities, e-Moderation, and the 5-Stage Model be applicable and designed to cater for Social Presence?

How might E-tivities, e-Moderation, and the 5-Stage Model, be applicable and designed to cater for Teaching Presence?

How might E-tivities, e-Moderation, and the 5-Stage Model, be applicable and designed to cater for Cognitive Presence?

1.2. Definitions of Special Terms

E-tivities are defined as "frameworks for enabling active and participative online learning by individuals and groups” [

6](p. 5), and are utilised in online learning in order to create a clear structured opportunity for learners to participate and interact collaboratively with the content, peers and the e-moderator. They are utilised as a means of seeking and acquiring a deeper understanding and connection to the content of the learning. The foundations of E-tivities include constructivism, situated learning and social learning theories [

6,

15], which are integral components in "well rehearsed, principles and pedagogies for learning" [

6] (p. 1). E-tivities are utilised weekly and consistently through course modules, are recommended to be deployed in groups of 25 people maximum [

15], and have a very distinct structure in their design. Please see Salmon (2013) page 3 for an overview of the structure of an E-tivity.

E-Moderation [

16,

17] is a term used to describe a particular strategy of interaction between the online instructor and their students. According to Salmon [

16] the role of the e-moderator is described as "promoting human interaction and communication through the modelling, conveying and building of knowledge and skills" (p. 4). E-moderating skills [

16,

17] include the use of weaving (integrating online student responses and probing, or questioning areas of further discussion—particularly through the use of E-tivities), and summarising—a succinct summary of learners’ responses to the module topic discussions, that explores the deeper context of learners responses and knowledge acquisition. An e-moderator is expected to be sensitive to the online learner’s experience and have high levels of emotional intelligence. An e-moderator should display "self-awareness, interpersonal sensitivity and the ability to influence" [

17] (p. 104). Emphasising the constructivist principles of quality, personal and effective interactivity between the learner and teacher. See Salmon [

17] (p. 206) and Salmon [

6] (p. 184), for an overview of weaving and summarising strategies in e-Moderation.

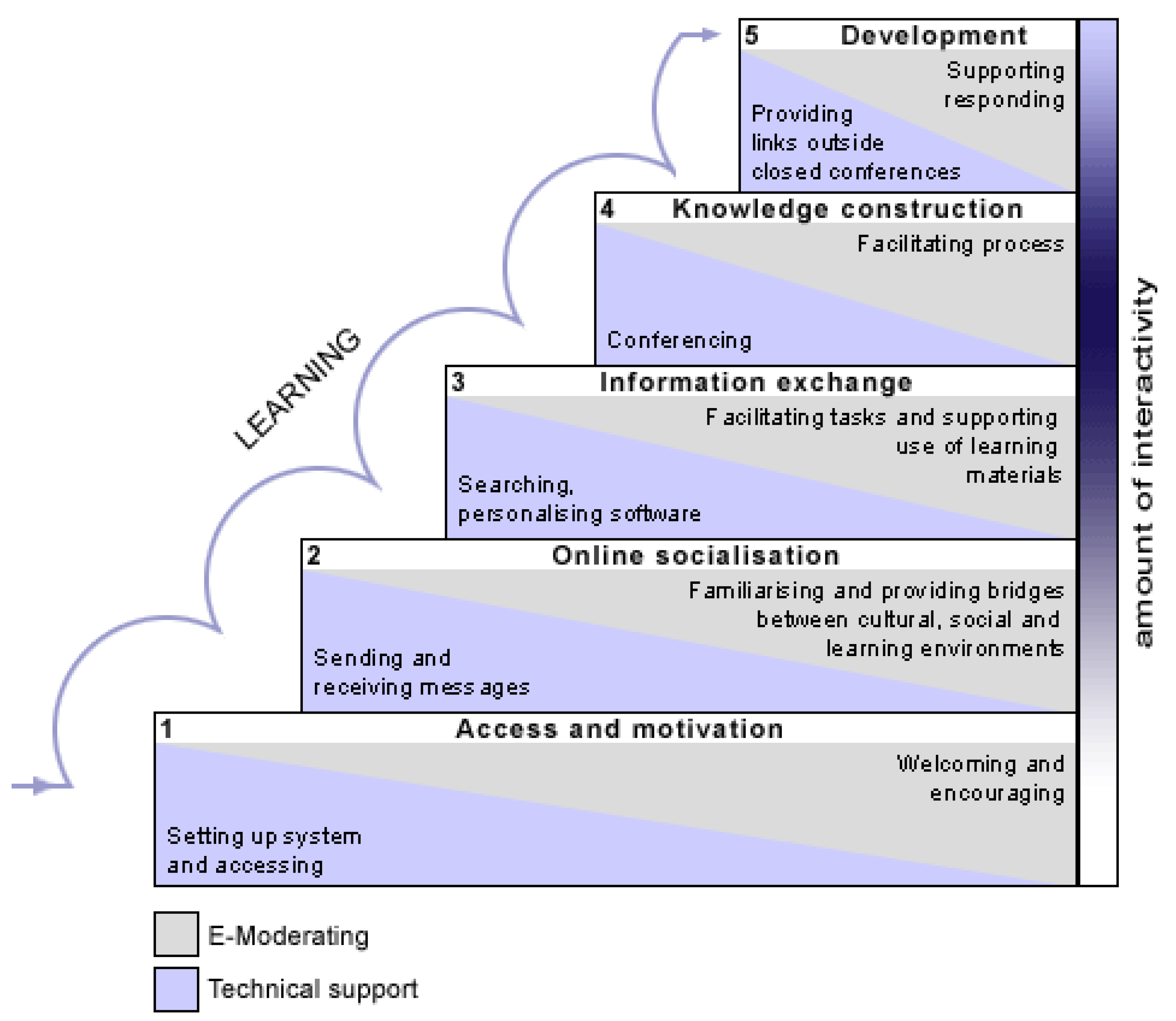

The 5-Stage Model [

17] is a scaffolded approach based on extensive research by Salmon, that structures course content and interaction around a natural stage-by-stage learning process the e-learner will naturally progress through in online learning, if courses are designed well. The model therefore provides the course designer a scaffold in which to design course content and structure, with the integration of specific stage appropriate E-tivities to meet the individual online pedagogy needs of the learner [

16,

17]. This links directly to providing a valid strategy for meeting learner satisfaction in Course Structure and Organisation (CSO) factors.

Figure 1 displays a direct image replication of the model and the information of the stages involved from Professor Salmon’s (2014) website.

Figure 1.

Salmon [

17] 5-Stage Model [

18].

Figure 1.

Salmon [

17] 5-Stage Model [

18].

3. Results

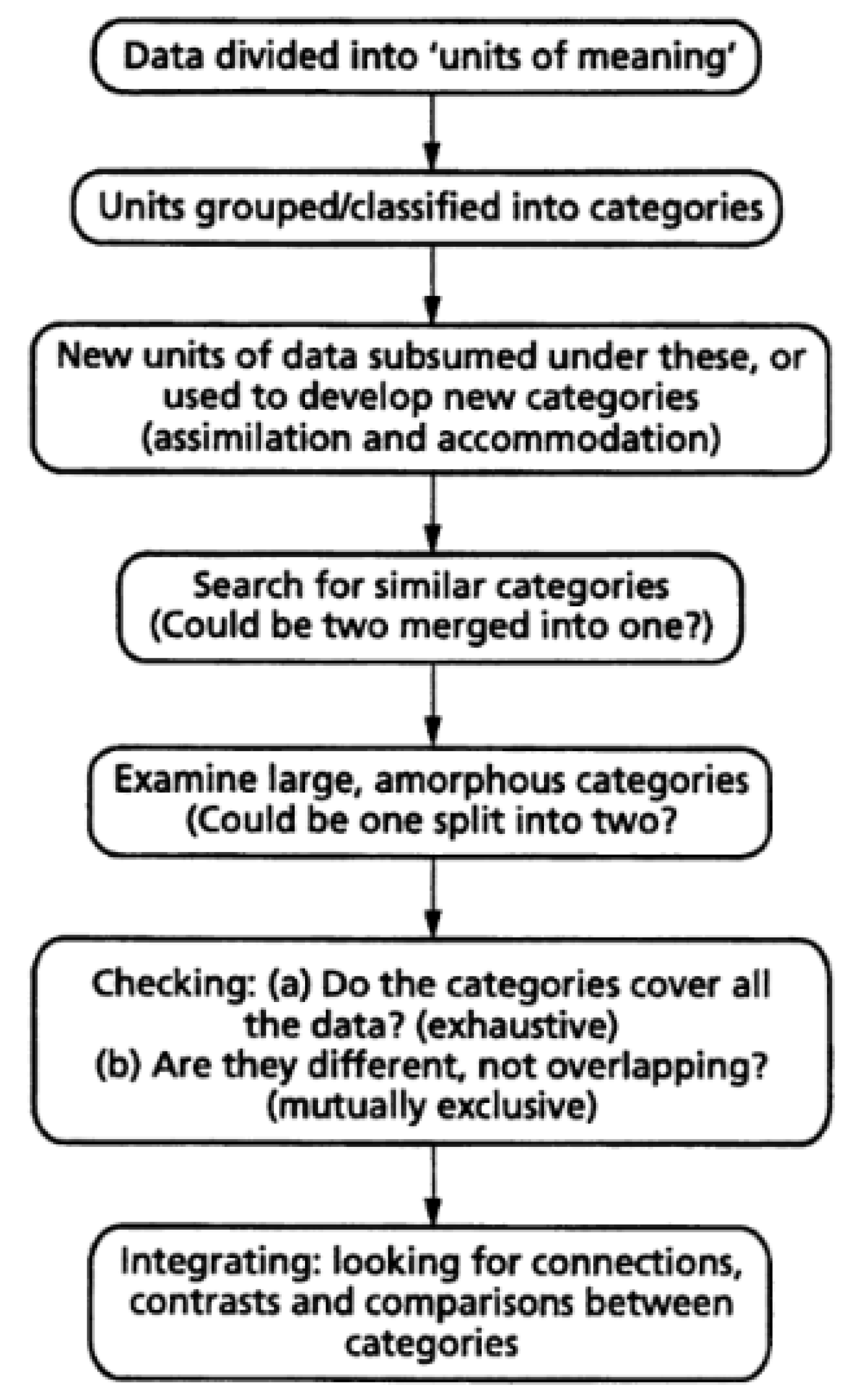

Three sub categories emerged when seeking to answer the research question “Are there key principle advice given for designing e-tivities in general that might be useful for future online educators”. These included “Reasons for using E-tivities”, “Benefits and Outcomes of E-tivities”, and “Challenges of E-tivities”. The following is a breakdown of the results that emerged around these three areas.

3.1. Reasons for Using E-Tivities

The participants expressed many reasons that they utilised E-tivities, mostly in relation to their previous success with them. Participants were largely exposed to the use of them during institutional change, and their “initiation” into the online learning environment. Participants reported their motivations for using E-tivities, e-Moderation and the 5-Stage Model was a result of their needs and desires for creating quality online learning design, after experiencing previous failures.

Table 4 below gives and outline into the reasons reported for using E-tivities,

etc., in their learning design.

Table 4.

Participants’ reasons for using E-tivities for online learning.

Table 4.

Participants’ reasons for using E-tivities for online learning.

| Reasons for using E-tivities

etc. | Number of participant responses |

|---|

| Adaptable across courses and disciplines | 3 |

| High quality experience | 4 |

| Highly engaging and interactive | 3 |

| Reliable and practical based structure | 3 |

| Same experience (or better) than face to face | 1 |

| Social Constructivist Design | 9 |

3.2. Benefits and Outcomes of Using E-Tivities

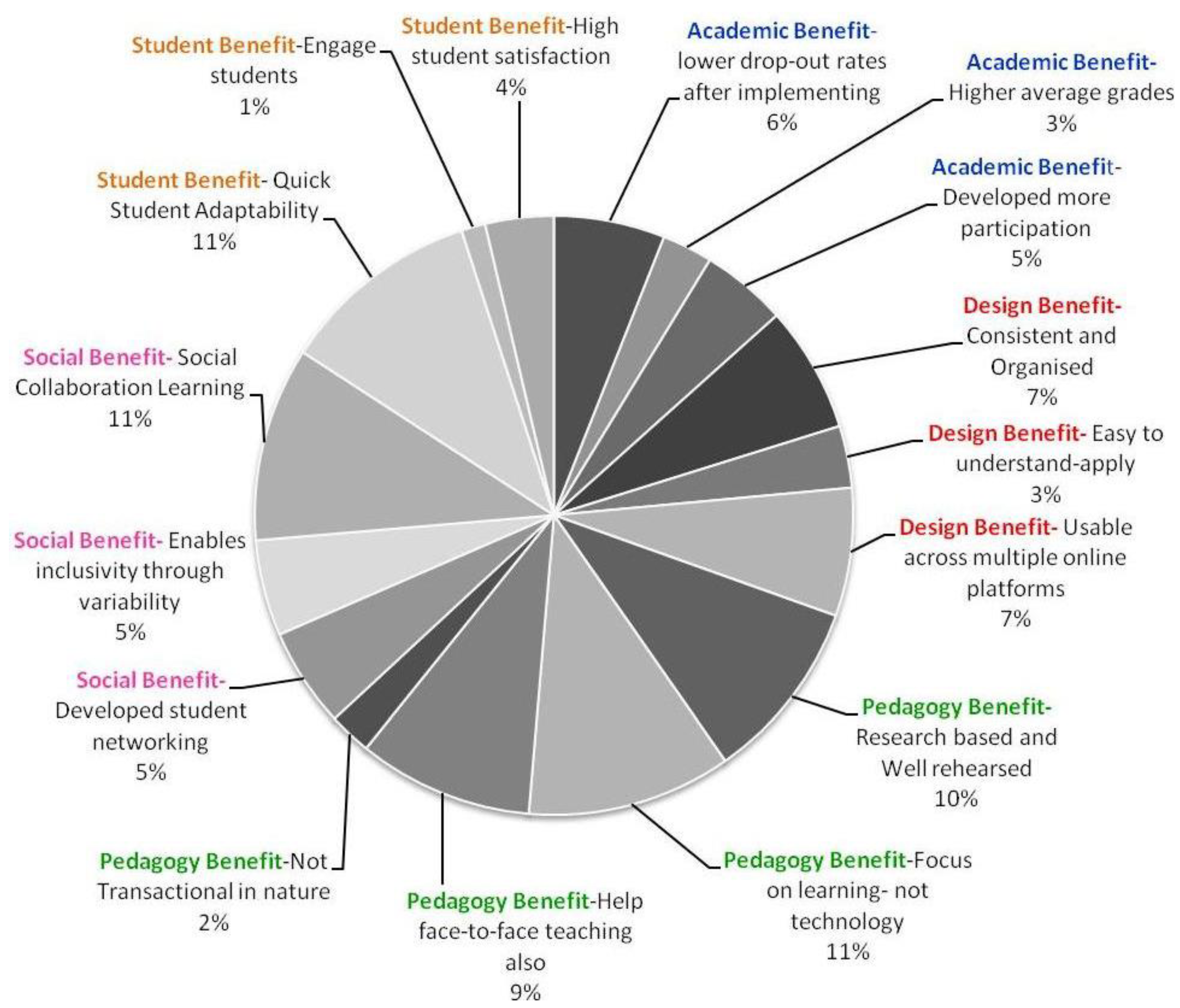

There were five overarching benefit categories to come out of the analysis. These five categories and the percentage discussed/reported included Academic Benefit (14%), Design Benefit (17%), Pedagogy Benefit (32%), Social Benefit (21%), and Student Benefits (16%).

Table 5 below provides a summary of these benefits and the corresponding CoI component that they could be seen to cover.

Table 5.

Overarching Categorical Benefits of E-tivities and their corresponding CoI framework components.

Table 5.

Overarching Categorical Benefits of E-tivities and their corresponding CoI framework components.

| Benefit of E-tivities | Descriptors | Matching CoI component |

|---|

| Pedagogy Benefit 32% | Research based, well rehearsed, helped face-to-face teaching, non transactional in nature | Cognitive Presence |

| Social Benefit 21% | Social Collaborative, enables inclusivity, developed student networking | Social Presence |

| Design Benefit 17% | Consistent and organised, easy to understand and apply, usable across multiple online platforms | Teaching Presence |

| Student Benefit 16% | High Satisfaction, Engaged Students, Quick Adaptability | Social Presence |

| Academic Benefit 14% | Lower drop out, higher grades, more participation | Cognitive Presence |

There were 16 sub-set benefits and outcomes reported in using E-tivities for learning design that dwelled within the five overarching categories.

Figure 6 below represents the percentage discussed/reported by participants of different benefits and outcomes, grouped by their categories

Figure 6.

Percentage of subset outcomes and benefits of E-tivities reported by participants.

Figure 6.

Percentage of subset outcomes and benefits of E-tivities reported by participants.

The highest benefits discussed by participants included the two Pedagogy Benefits of E-tivities, being based on research and well rehearsed over its years (11%), and that E-tivities enabled the focus to be on the learning and not the technology (11%). Other benefits highly discussed were the Social Benefit of Social Collaboration Learning (11%), however its category of “social” benefit could be debated, given that research into social collaboration learning design shows benefits of relating to all the categories of social, pedagogy, academic and student. However, given the nature of the theory, it was decided that the social category provided the closest match to the underlying principles of the theory for the purposes of this research. The other highly discussed benefit was the student benefit of how quickly and easily students can adapt to the learning design (11%). Specifically, as they become familiar with the structure over time, it allows them to not get caught up in the distractions of design and technology, and focus directly on the task at hand.

It is interpreted that Teaching Presence was not equally represented with regard to “benefits” specifically because the main topic of the blog posts were focused on E-tivities and the 5-Stage Model. Rather than e-Moderation which relates to the “teaching” component of Online Leaning, and would therefore be expected to reflect “Teaching Presence”.

It is noted that the highest reported benefit was in relation to Pedagogy, which is an important consideration for educators in any industry. It also underpins the principle argument that Salmon [

6] makes in regards to these methods providing a practical and step-wise solution for designing for pedagogy that reflects a learner-centred approach, from which all other educational outcomes can achieve success.

3.3. Challenges for Designing E-Tivities

All of the participants had their own specific individual and personal challenge in designing E-tivities, with only two participants over-lapping on one particular challenge. Thus, there were eight challenges in total out of nine participants, each challenge reported by a different participant. This could reflect that the constraints and issues relating to online learning design and delivery appear to be situational and content specific, at least in the situation of these participants.

Table 6 below outlines the eight key areas that were defined as being the challenges the participants faced in designing E-tivities.

Table 6.

Challenges for designing E-tivities as reported by participants.

Table 6.

Challenges for designing E-tivities as reported by participants.

| Challenges for Designing E-tivities | Number of participant responses |

|---|

| Balance between personal and discipline related content to generate knowledge sharing | 1 |

| Difficulties with learning to design cross culturally (designer issues rather than issues with E-Tivities specifically) | 1 |

| Hard to predict students experience of an E-tivity | 1 |

| Technology restricted by institution-limits creativity | 1 |

| Unreliable technology make design more time consuming | 1 |

| Stage 1 and 2 crucial to ensure other stages will work | 2 |

| The importance of feedback on developing E-tivity designs (hard to do it alone) | 1 |

| Challenge of balancing creativity and academic content | 1 |

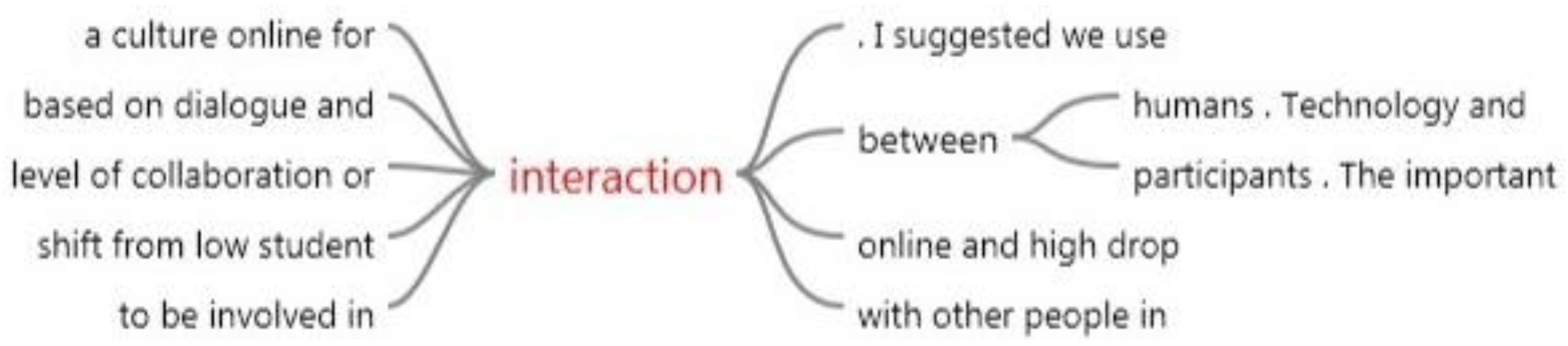

3.4. Social Presence in Design

In order to answer the research question “

How might E-tivities, e-Moderation and the Five- Stage Model, be applicable and designed to cater for Social Presence”, text evaluation, and content comparison analysis for Social Presence indicators were reviewed. A number of ideas emerged and these were summated into overarching concepts that grouped themselves naturally into the three categories within Social Presence (Affective Expression, Group Cohesion and Open Communication). The results are demonstrated below in

Table 7, along with the percentage that each of the learning design ideas were discussed in relation to the whole topic/indicators of design that aligned with Social Presence. They have also been ordered from most discussed, to least discussed. This table provides a combination of explanations and suggestions that related to designing for factors of Social Presence, but also for how E-tivities have demonstrated (in the participants’ experience) an element that could be categorised as Social Presence. Interpretation and possible inferences to be made from these results will be presented in the discussion section.

Table 7.

Areas of designing and E-tivities that align with Social Presence indicators.

Table 7.

Areas of designing and E-tivities that align with Social Presence indicators.

| | Affective Expression | Group Cohesion | Open Communication |

|---|

| | Use multiple platforms in designing enabled connected discourse | Keep your design constant and connected to the learner | Multimedia approach provided more options for conversing and interacting |

| 17.2 | 16.26 | 12.8 |

| Voice boards for Affective expression | E-tivities in Virtual Worlds for Group Cohesion | Technologies such as Blogs, email, Skype used for open communication |

| 9.41 | 10.8 | 8.2 |

| Were able to measure the degree of emotional involvement students | Take time to create a safe environment | Wikis allow for more reserved students to participate at a level comfortable to them |

| 6.8 | 3.92 | 3.6 |

| Ability to build groups and develop authentic connecting | Make the most out of stage 2 for creating authentic group connections | E-tivities on discussion boards have potential for more detailed communication |

| 3.17 | 2.06 | 2.9 |

| Importance of designing for socialisation before exposing students to complex technology | | |

| | 2.88 |

| Total Percentage | 39.46% | 33.04% | 27.5% |

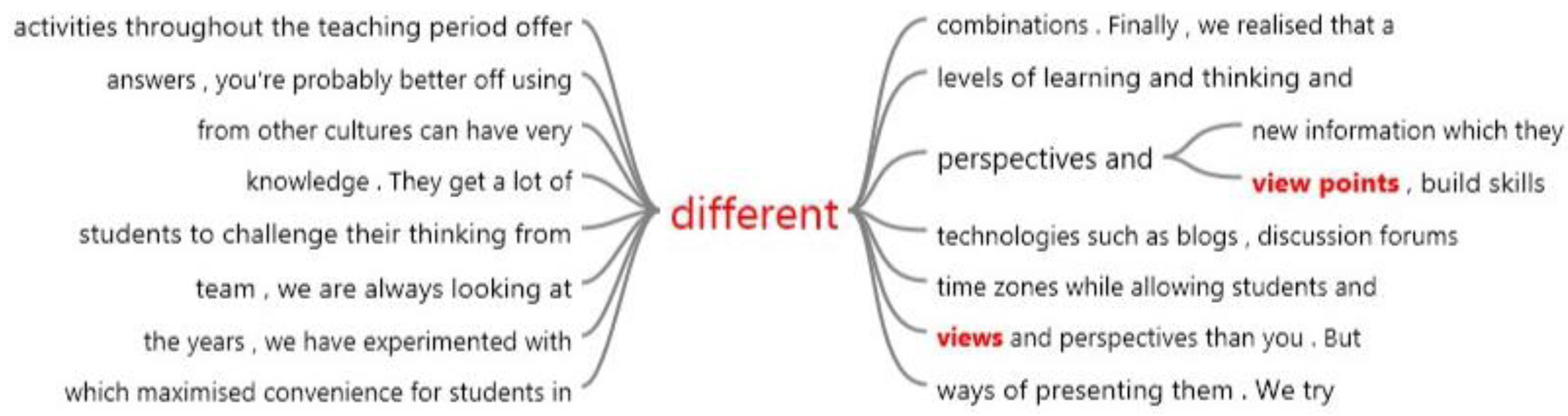

3.5. Cognitive Presence in Design

In order to answer the research question “

How might E-tivities, e-Moderation and the Five- Stage Model, be applicable and designed to cater for Cognitive Presence” text evaluation and content comparison analysis for Cognitive Presence indicators were reviewed. The results are demonstrated below in

Table 8, along with the percentage that each of the learning design ideas were discussed in relation to the whole topic/indicators of design that aligned with Cognitive Presence. They have also been ordered from most discussed, to least discussed. This table provides a combination of explanations and suggestions that related to designing for factors of Cognitive Presence, but also for how E-tivities have demonstrated (in the participants’ experience) an element that could be categorised as Cognitive Presence. Interpretation and possible inferences to be made from these results will be presented in the discussion section.

Table 8.

Areas of designing and E-tivities that align with Cognitive Presence indicators.

Table 8.

Areas of designing and E-tivities that align with Cognitive Presence indicators.

| | Triggering Event | Exploration | Integration | Resolution |

|---|

| | Sparks need to be relevant, not just decorative | Design with rewards and incentives for participation based on intrinsic and motivation | Using certain technology (e.g., voice boards) applied appropriately can lead to self-instigated learning and developing new resources | Design for practical, hands-on applied learning |

| 8.48 | 11.98 | 11.01 | 12.12 |

| Use of imagery to create a spark of designing inspiration | E-tivities have to be considered useful to participants | Design towards learning outcomes and assessment for knowledge acquisition | Design e-tivities that reinforce previously skills (e.g., research) |

| 6.24 | 7.55 | 7.06 | 7.20 |

| Importance of capturing, grabbing or engaging the participants interest | Offer diverse activities in order to enable participant learning differences | Oral type activities create deeper analysis and understanding | Scaffolded assessment to skills acquired |

| 3.76 | 6.82 | 8.14 | 6.41 |

| Technology (info graphics, photos, videos, music, games) as sparks enables more engaged interaction from the outset | E-tivities have to be drivers of learning, not add-ons to it | | |

| 1.17 | 2.06 | | |

| Total Percentage | 19.65% | 28.41% | 26.21% | 25.73% |

3.6. Teaching Presence in Design

In order to answer the research question “

How might E-tivities, e-Moderation and the Five- Stage Model, be applicable and designed to cater for Teaching Presence”, text evaluation and content comparison analysis for Teaching Presence indicators were reviewed.

Table 9 on the following page demonstrates the results of Teaching Presence indicators, along with the percentage that each of the learning design ideas were discussed in relation to the whole topic/indicators of design that aligned with Teaching Presence. They have also been ordered from most discussed, to least discussed. This table provides a combination of explanations and suggestions that related to designing for factors of Teaching Presence, but also for how E-tivities have demonstrated (in the participants’ experience) an element that could be categorised as Teaching Presence. Interpretation and possible inferences to be made from these results will be presented in the discussion section.

Table 9.

Areas of designing and E-tivities for aligning Teaching Presence indicators.

Table 9.

Areas of designing and E-tivities for aligning Teaching Presence indicators.

| | Design and Organisation | Facilitation | Direct Instruction |

|---|

| | Get feedback on designs | Design for e-moderator’s time | Prepare clear instructions for technology that has a steep learning curve (e.g., wikis) |

| 20.47 | 5.21 | 3.27 |

| Limit complexity of e-tivities; or rather keep it simple | Active e-moderators are integral | Prompt participants to log in regularly |

| 13.42 | 3.69 | 1.69 |

| Create an environment that’s logical/consistent to the participants | Relatable and authentic | Use visuals for technological instructions at Stage 1 (of the 5-Stage model) |

| 9.49 | 3.36 | 1.27 |

| Expect/ensure E-tivities are allowed to evolve and change | e-Moderator as role model or coach | |

| 7.57 | 2.95 | |

| Design effective but time efficient e-tivities | Approachable and caring | |

| 6.72 | 1.97 | |

| Use course objectives to design wording of E-tivities | | |

| 4.73 | | |

| Test the technology | | |

| 3.42 | | |

| Ensure there is quick access to knowledge/information for participants | | |

| 3.4 | | |

| Design for easy navigation | | |

| 2.89 | | |

| Use existing platforms and designs where possible (e.g., OERs) | | |

| 2.31 | | |

| Utilise mind maps for designing ideas | | |

| 2.16 | | |

| Total Percentage | 76.58% | 17.18% | 6.24% |

4. Discussion

With regards to Social Presence results, it can be noted that the highest reported E-tivity designing principles were those that aligned with the Affective Expression (39.46%). However, Group Cohesion (33.04%) and Open Communication (27.5%) were adequately represented also. What is worth noting is the highest percentage design principles within each category. Specifically, it is the E-tivities’ ability to be designed and used across multiple platforms that allowed for creating larger discourse opportunities (Affective Expression). Secondly, that in order to design for group cohesion, the most commonly mentioned design principle was keeping the design consistent and focused on the learner. E-tivities already have a consistent template for designing which should make this element easier for online educators to cater for. Lastly, the use of multimedia in E-tivity designing was reported by designers to enable more interaction and conversing opportunities amongst learners (Open Communication).

With regards to Cognitive Presence results, interestingly the four indicators of Cognitive Presence categories were relatively evenly distributed. While more examples for designing for Triggering Events and Exploration were given—matching Garrison’s [

32] comment that these two areas are easier to design and measure for—quality design strategies were discussed for the other two, with design strategies reflecting the role that technology can play in enabling stronger Integration properties such as reflection, explanation and understanding concepts. In addition, it reflects the focus of strategic practical content and design scaffolding that seem to target Resolution principles of practical application, solutions, external and real-life application.

With regard to Teaching Presence results, it is relevant to note that this presence had the highest instances of designing importance discussed even though it had the lowest reported “benefit” of E-tivities—the latter likely to be a reflection of the focus on E-tivities in the blogging topic, rather than e-Moderation, which is Salmon’s [

17] specific strategy for teaching online. Specifically, the importance of the design and organisation of the course were discussed as the most important teaching factors (76.58%). This supports Garrison’s [

32] and Garrison

et al. [

33] assertion, as supported by the research into this presence over the last decade, on how important this factor is on creating sustainable and successful online learning. As well as the importance of laying the correct foundations from which a successful course, and therefore appropriate teaching presence, cognitive presence and social presence can grow.

5. Limitations

Obviously there are limitations of this research from many different avenues, including issues in generalisability outside of this particular case study approach and the small sample size. There are limitations in the qualitative and exploratory research design as being seen as lacking in empirical evidence for a relationship between the variables. Further limitations include issues with the data being pre-existing and not directly written by the participants with any context of CoI applications. However, if you were to consider this in part, an observational approach almost, hearing from designers in the field without influencing their answers or directing their questions towards CoI applications—as would have been likely in a more traditional research design—then there are implications here for findings to have some merit. Specifically given the reflective nature of a blogging platform and potential metacognitive process evolving in the participants’ content.

Further limitations have to be considered in the participants’ demographics. The majority of the participants are not only supporters of these particular learning and teaching methods, but are considered “experts” (six having 5+ years experience) in the application and design of E-tivities, e-Moderation and the 5-Stage Model. They have many years of experience in the methodologies and have explored them across multiple platforms, contexts, institutions and disciplines. Therefore, it cannot be assumed that more novice designers would be as apt at designing strategies that catered to the CoI framework. It could also be hypothesised that as these experts have been in the industry for so long, that they are also well versed and supportive of the CoI framework, and could be organically designing for these components without the influence of the methodology design at all.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

It could be concluded by this research that there is some potential support for an alignment between the CoI framework being operationalised through the use of E-tivities [

6], e-Moderation [

17] and the 5-Stage Model [

6]. This study has shown that there is some possible overlap in learning design strategies. There is some support that if online designers were looking specifically at “how” to design for Social, Cognitive, and Teaching Presence, as per the research questions of this report, that utilising these Salmon specific strategies is likely to be an appropriate approach to take. Specific interesting conclusions that emerged from this study included the potential connection of the use of technology and designing through these strategies, in order to cater to the complexities of Integration and Resolution phases of Cognitive Presence. This is important, given the current research into this area has been unable to not only identify the progression of participants through these phases [

34], but that according to Garrison

et al. [

33], correct learning design strategies for these phases is at the bedrock of this issue. This research has highlighted the potential to utilise these Salmon strategies for catering to this designing issue. The research has also supported Garrison

et al. [

33] assertion for the importance of a solid learning design strategy that centres around the importance of the teacher and their presence. Research into online learning suggests the most reported area for dissatisfaction/satisfaction in the online learning environment was the quality of the encouragement, feedback, counselling, facilitation, respect and instructional quality of the teacher [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. In other words, their “teaching presence”. It is not innovative to suggest the role of the teacher in learning is a pivotal one, and yet online students still continue to be dissatisfied with their experience and their engagement with their teachers. Some research [

40,

41] suggests that the reason for this is because teachers are often not adequately confident or literate in online teaching skills or pedagogy, and that those with less exposure to online learning have less positive views of its implementation [

42]. Further research stressed the importance of continuing exposure to, and education in, online instructing for teachers [

38].

With this in mind, it stands to reason that initial recommendations based on this research include training online educators in the strategies E-tivities, e-Moderation, and the 5-Stage Model which would have the potential to not only widen online teachers’ capabilities, but potentially target and identify teaching and design capabilities that cater to these integral CoI components. However, in order to truly support this initial hands-on outcome recommendation, additional research specific recommendations would be suggested. These recommendations include the creation of an empirical based study that directly measures the presence of CoI in these learning and teaching design strategies while they are in action. The best situation of this would be the utilisation of the CoI Survey Instrument (draft v15) [

13,

31] with participants of courses that are specifically designed with these Salmon methods.

However, putting aside the limitation debate between qualitative and quantitative data collection approaches in research, held most strongly it seems in the social and educational research environments [

20], there has still been merit in the current researcher’s investigation into this topic. This research has had the potential to shed some light, become a pathfinder even, on not only the complexities of designing online courses that meet the complex criteria of the CoI framework, but also simply to highlight the merit and importance in utilising a structured, well-rehearsed and appropriate pedagogy approach to any design of an online course. While one would think this advice stands to reason, the truth is that the current experience of the average online student with their teacher is one of great disappointment [

43,

44]. It is not to say that there are not innovative and passionate educators out there who care about the impact that the design of their online courses will have on their students. The unfortunate truth is that a decade on, the vast majority still do not meet these now scientifically supported conclusions for how to engage and support the online student in the best possible way. As there has been much support for the CoI framework in research for the Presence elements in being important inclusions in online design, this e-learning design strategy is readily available and has the potential to cater to these CoI frameworks. There are even professional development workshops that teach these strategies in a two-day team process event called “Carpe Diem” (see [

45,

46] for more information about Carpe Diem’s). Or alternatively perhaps the developers of the CoI framework, or their own front line supporters, could explore a professional “marriage” between these design theories.

It is not innovative to suggest that teachers in Higher Education should possess the most up-to-date knowledge in their chosen field of expertise. However, perhaps more importantly, they should possess the same level of expertise in effective and innovative delivery of that knowledge to their students [

47]. It is the conclusion of this researcher that it is important that Higher Education Institutions continue to pursue the requirement of teaching qualifications for their educators; and at the very least, they should provide ample time and support for educators to participate in professional development training of this nature. As well as ensuring that practical and hands on approaches of the important components of teaching and designing e-learning, form an integral part of the syllabus within the growing number of Graduate Certificates in Higher Education. While this research does not conclude that these Salmon methods are the only teaching and designing methods available that might be appropriate to meet these needs, it does argue and suggest that they are definitely one method worth trying. That, ultimately, it is the passion of this researcher that not just online educators, but the institutions that house them, encourage the implementation of high standards of learning and teaching design in the online environment. If the ultimate goal and argument for the relevancy of higher education in the professional world is that of producing individuals who bear a high standard of training and quality knowledge in their specific discipline, then the expectation is that the institutions should lead this, first and foremost by example. By ensuring that their teachers actually know how to teach, rather than simply being experts in the field that they teach. For one of the key principles in successful knowledge construction within students is how well their educators deliver that knowledge, effectively and inspirationally. Something that the culture of academia seems to have sidestepped, or even worse, appear offended at the very idea that they could be described as a “Teacher”. This means however, that administrators of institutions, and indeed the culture of Higher Education needs to consider shifting their focus from research driven rewards and incentives. By, rather, giving adequate support, incentive, rewards, and perhaps most importantly time, for the inspirational educators that are willing to be the representation of the quality training they provide, by ensuring they are appropriately trained themselves. For it is inspirational educators that produce inspirational students, who go out and be the change this world so desperately needs. Which is, after all, at the very least half of the main contribution that Higher Education is meant to be providing to our society in the first place.