School Leadership and the Professional Development of Principals in Inclusive and Innovative Schools: The Portuguese Example

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Leading learning and teaching;

- Promoting their own professional development and that of others;

- Leading for improvement, innovation and change;

- Leading school management;

- Involving and working with the community.

- Defining a direction (vision, expectations, goals);

- Professional development;

- Redesigning the organization (collaborative culture);

- Managing the teaching–learning processes.

- Ensuring that all students learn;

- The existence of a collaborative culture where people work together to achieve common goals;

- Improving results.

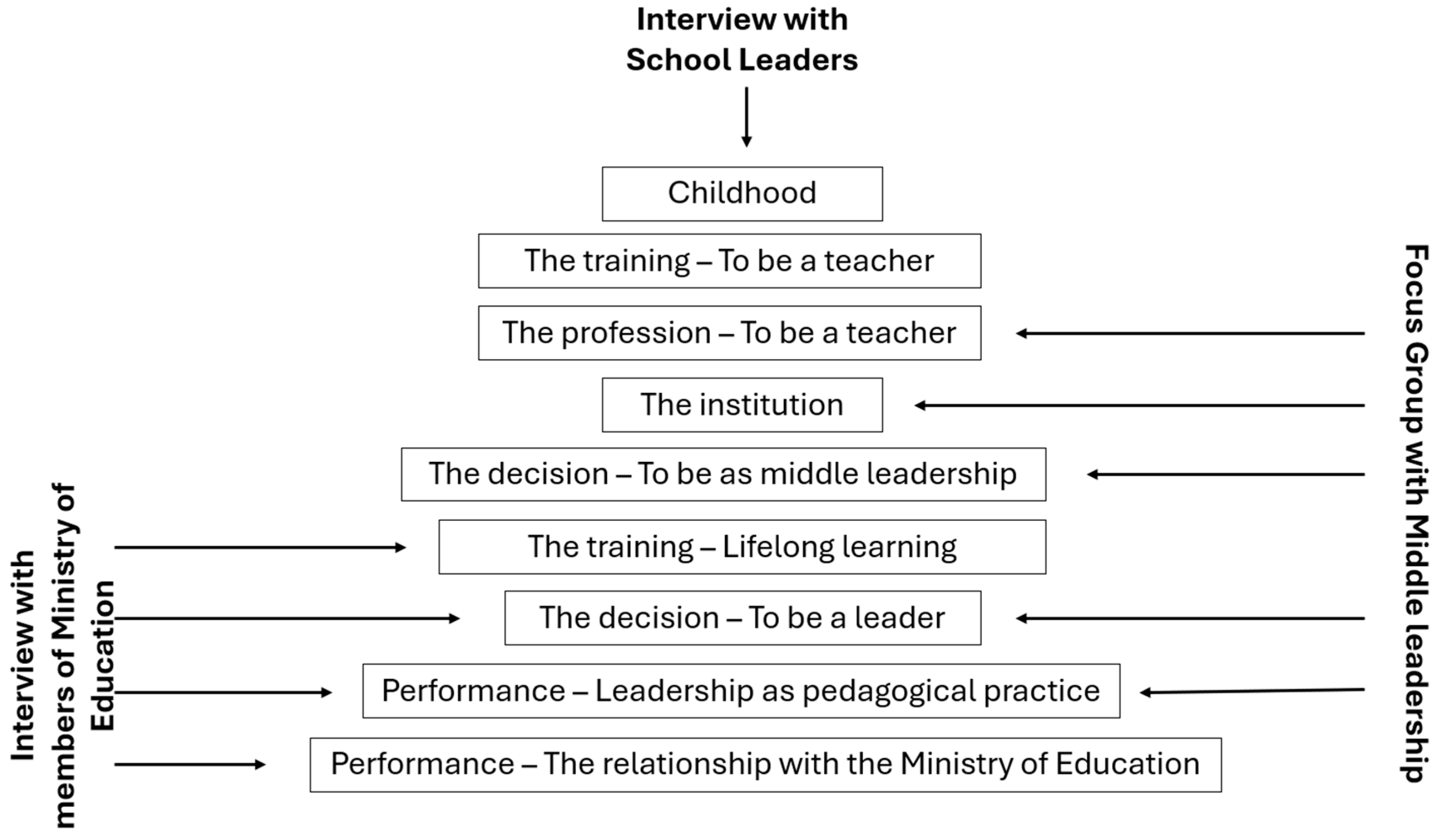

2. Materials and Methods

- i.

- First interview: chronological exploration of the career, transcribed and subjected to analysis, present in the attached script through the parts of childhood; training—in teaching, the profession, the institution; the decision—to be a middle leader; training—in school administration; the decision—to be a principal; the performance—leadership as pedagogical practice and the relationship with guardianship;

- ii.

- Second interview: exploration of blank questions or in-depth study of some categories not explored in the first interview, as well as generalized reflection on the overall experience of the career, in this case, the decision—to become a headteacher; the action—leadership as pedagogical practice and the relationship with the board. The interview was then transcribed and analyzed;

- iii.

- Third interview: discussion of the interviews and reflection on the analysis carried out.

3. Results and Discussion

It means my whole professional life, which also includes part of my personal life. My friends were built here too—my life was lived here with all these people, non-teaching staff, with some teachers who I’ve always known here too. They’re good friends. This school means life; it means life—I can tell you that.(Mário Rocha)

reducing school dropout and strengthening institutional autonomy, promoting flexible, innovative interventions tailored to the specific needs of students and their families. In addition, it promotes the sustainable development of the local community, with strategies that respond to vulnerability factors, such as the high percentage of beneficiaries of school social action, students whose mothers have less than 12th grade education and migrant students.(Educational Project, p. 6)

We also have to make a big commitment to training and the possibility we have of having our own LeiriMar training centre (…) participate in partnerships and projects with other institutions and, above all, with higher education institutions. (…) We’ve already had the project of intervision of classes, (…) pedagogical pairs are the best intervision strategies that we’re also having, because people are in the same space, they’re sharing methodologies, and they’re sharing strategies—how can we do this; how can we do that—and they discuss it and then there’s already one who can do it. There’s a lot of the process; it’s a process that’s discussed a lot among themselves and that’s why I think it’s very important. (…) So I did a DCA last week. And I shared our vision of some of our documents, reflecting on the issues of the descriptors and I felt that people were thinking when I told them something as simple as this: making the performance appraisal report for those who are in this cluster requires, first of all, understanding which descriptors are in force in the cluster (…) And arriving at the end of two and a half hours and discussing these aspects and hearing people at the end say I never had an integrated notion of the appraisal process.(Cesário Silva)

We organize a lot of workshops, a lot of moments of sharing that mainly go towards what we think are the main weaknesses that may still exist in the cluster, in some way to try to address these weaknesses (…) in some department meetings, when the information isn’t that much, we promote moments for the person to feel like looking for some more knowledge.(FG SC Cristelo)

Training that starts by being internal training, in the sense of also encouraging internal training that is shared and collaborative work, such as workshops that we do regularly. We can even say that we have panels and workshops here at least three times throughout the year in which we promote internal training, but then we also have discussions every month to take stock of what is being done and also to listen to the students, to listen to the educational community. And this is one of the most significant strategies, in terms of promoting active learning methods and also encouraging pedagogical practices.(Mário Rocha)

They attend training which is then an asset to the work they do in the workshop context. On the other hand, we hold monthly meetings and create situations for sharing, even of tools.(FG SC Marinha Grande Poente)

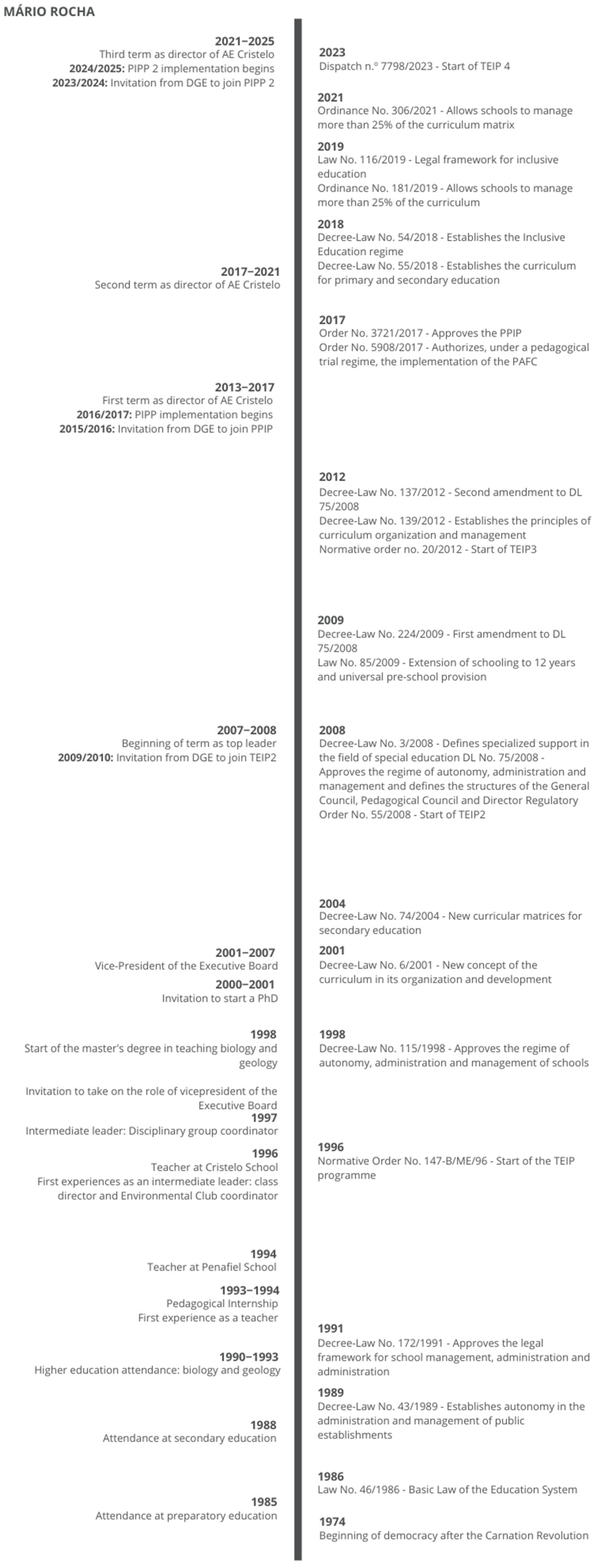

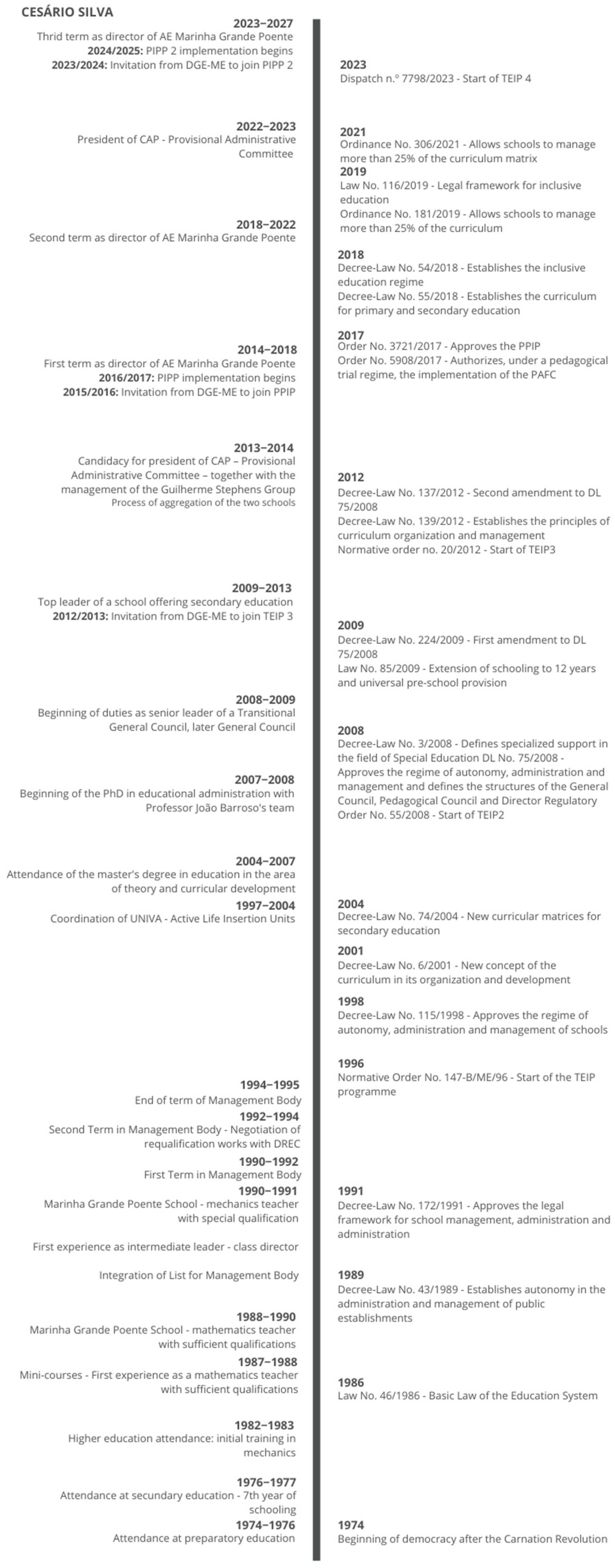

3.1. Further Education

I think so. I think there’s a family characteristic, which I think is also relevant in this sense. I’m the first to have a university degree, the third son and the first to have a university degree. And nothing could have been expected—I have this notion—if April 25th hadn’t happened. Because what would you expect from the son of a truck driver and a maid? You wouldn’t expect anything other than elementary or compulsory schooling and then going out into the world of work. But no, fortunately I got through this transition cycle, even though I always felt that my family valued education and school as important, and even my sisters, who were older, always felt that I valued this aspect a lot and would help and support me so that I would actually invest in my schooling. So that’s what happened.(Cesário Silva)

So, as a student, I was always, from a very young age, very fond of studying, perhaps because I was also in a family where I was the first one to study, or to study further, so as this was a lot. This responsibility was very much placed on my shoulders, by my parents; I also felt a certain obligation to study—I don’t know—but I liked it.(Mário Rocha)

3.2. Initial Training

It never crossed my mind, it wasn’t until the third year, when I was already in science, that I switched to education and decided to become a teacher. (…) We had a very thorough scientific preparation, no doubt about it, but we had no preparation for teaching, or for training people, absolutely nothing. (…) I didn’t feel that any of it had much application in my day-to-day life. And, in fact, my great, great training was when I did my teaching internship. Then, yes, I felt that I began to learn, because the teaching internship was also accompanied by a monograph, which we had to do, and which obliged us, once again, to revisit all the didactics and all the educational psychology. And then, yes, I felt that I deepened my knowledge a lot more. I started to take a lot more interest in this, and I felt that the internship, and I still think so today, the pedagogical internship was fundamental to my training as a teacher, as initial training.(Mário Rocha)

Now, I remember her perfectly because she was wonderful. She taught us fantastic things: how to approach a class, techniques for dealing with students’ difficulties. She was a wonderful teacher, a wonderful advisor, and a lifelong friend. She was much older, but she taught us a lot. I think that’s when you realize how important experience, pedagogical or didactic knowledge is in training people, and she was a wonderful human being too, and she made us feel that this teaching profession could be a wonderful profession if we also embraced it with passion. And she transmitted that passion to me. I really enjoyed it. I was lucky enough to have this advisor who opened my eyes.(Mário Rocha)

Then, after completing my master’s degree, perhaps in 2007, I was also a little challenged to continue with my doctorate and, therefore, I took a short break here, perhaps for a year, and started a doctorate in school organization and management in Lisbon, with a fantastic team. I’ve always had fantastic teams of teachers, who I think end up being more like mentors than teachers and, above all, who share knowledge, life experiences and very positive things.(Cesário Silva)

And then I went to work in this area of school organization and administration with Professor João Barroso and his team, as well as with Professor João Barroso, Professor Natércio Afonso, Professor Luís Miguel Carvalho, and also with Professor Madalena, I think it was the four of us, it was a team of four with whom we worked and we had our training project for our first year of the doctorate. (…) At the time, I feel that this whole process of what was a normative edifice on which our education system was based had a whole process of continuities and discontinuities, it’s true. But it made us immerse ourselves a lot in this dimension and, above all, in the evolution of the margins of autonomy, of the issues that were spaces that schools could appropriate in order to be able to build what was their identity, their culture and also have the possibility of working in another way that wasn’t strictly very homogeneous, with room for openness. And also realizing that this whole group of trainers led us to a lot of discussion and very deep reflection and, above all, to learning how to do something that was very much a documentary analysis of some important processes, a content analysis of some regulations and this polysemy that some words contain and being able to understand the context of their applicability; sometimes being able to understand what the legislator’s intention is when he tries to make certain information explicit, how that preamble to a regulation is constructed and so on. So, in that respect, it was very rich and, above all, it was very challenging because it also allowed us to be in contact with others, with the reality and with educational systems in other European countries where we were also sharing some experiences and, above all, realizing this diversity between many systems, from more centralized systems like ours, to very decentralized systems, to systems like the Spanish system, which is very regional and then municipal, and all these processes were very important from that point of view.(Cesário Silva)

3.3. Experience on Management Bodies and Lifelong Learning

Well, the truth is that it never crossed my mind, but the point is that I was, I was vice president for six years and after six years, there ended up being a break with the president at the time (…) and the truth is that after various contingencies, I ended up putting forward a team for the Executive Board. We went ahead, we thought we were going to win and we did; in 2007, we won the governing body. That same year that we were elected, the very next year the possibility arose of doing a postgraduate course in school administration at the University of Coimbra and so it was, the three of us went to do the school administration course at the University of Coimbra. Later, with the publication of Decree-Law 75/2008, there were applications for the position of principal and I applied for the position of principal and stayed on.(Mário Rocha)

I’m a big believer that we should always learn in certain positions. The more we learn, the more we can deepen our knowledge, and the better we are in the job we’re going to do. I felt that there were a lot of people there that I got to know and one of them ended up being our first external expert later on at TEIP; she was our postgraduate teacher and ended up becoming a personal friend of all of us and we still have her as such today. But the postgraduate course was very important for me to be able to do the job in the way we have been doing it ever since. Not just me, but also the rest of the people who did their postgraduate studies with me.(Mário Rocha)

3.4. The Educational Territories of Priority Intervention (TEIP) Programme

Back in 2012, as a secondary school, we had joined the TEIP programme, Territórios Educativos de Intervenção Prioritária (Educational Territories of Priority Intervention), and when I was called to Coimbra to be asked if we would be available to join this project, the first thing that popped into my head was to think like this: TEIP at the time still had a less positive connotation and, above all, we were a school where there was and there still is a great deal of socio-economic and socio-cultural heterogeneity. But it could be an asset and, above all, it had to get here and I couldn’t say that we were an Educational Territory of Priority Intervention in that way. Yes, that’s right, it was already at that last stage when we joined, and we had to meet with the school and the teachers and the parents’ association and all those structures, and also with the staff to pass on this information and raise awareness. We had to dismantle this and when I came here from Coimbra, a thought went through my head, which was to say we’re not going to be a TEIP, we’re going to be a TEIPS and, so that’s what I said to the school: “Look, we’ve been invited to join the Educational Territories of Priority Intervention and we’re going to accept joining the Educational Territories of Inclusion and Promotion of Success, TEIPS”, so that’s what we’re going to be, an Educational Territory of Inclusion and Promotion of Success. And that way we’ll have a few more resources to be able to respond to our students’ needs, we’re going to have the chance to join a team here in the student and family support office, because we’d already come from projects under the Escolhas programme, which worked a lot with disadvantaged young people and families with economic and social needs, so there was already a bit of a leverage of situations and this transition was very smooth. We never felt any stigma, people never associated us with this issue and so, in 2012, we once again took on another challenge and, having just started this process, we were discussing the reorganization of school clusters in Portugal at the time.(Cesário Silva)

We were in 2008, here in 2008, exactly, I think, around May 2008, and we were invited to be included, invited in quotes, because in fact what happened was that we were forced to be included in the TEIP 2 programme. At the time, as you can imagine, TEIP still had a very strong stigma, in the sense that those who went to TEIP, or the schools that were included in TEIP, would eventually be schools with various problems, in various dimensions. At the time, when the DGE-ME called me, I was very surprised and asked why, why it had to be, and what they said was, it has to be, it has to be. You have to be included, given your socio-economic background and also your failure rates, especially in the third cycle.(Mário Rocha)

Firstly, it’s funny that we took the acronym TEIP, the Território Educativo de Intervenção Prioritária (Educational Territories of Priority Intervention), and reworked the vision we’ve had for this cluster since the beginning, which has to do with Work (=Trabalho), Ingenuity (=Engenuidade), Inclusion (=Inclusão), and Progress (=Progresso). We took the letters of TEIP and turned them into this.(Mário Rocha)

And all of this completely revolutionized and also contributed enormously to our TEIP educational project gaining consistency. So, that first year I had as president of the Executive Board, first, it was more or less two years until I was elected principal, it was already at the end of 2008. But 2007–2008 and then 2008–2009 was very important, both because of the training I had personally and because of the contact I had with the TEIP programme, as it is now called, which empowered me a lot in terms of what should be done at the level of an institution, and above all at the level of an institution that was concerned about improving, but which also didn’t know very well how to tackle a problem. And this involvement of both the top leadership and the entire team was crucial. I didn’t just do the TEIP training, it was my team at the time from the Executive Council, and I took some other members, department coordinators, to do this training with DEGEstE and DGE, and this gave us the extremely important know-how to get off to a good start in what was supposed to be the beginning of the TEIP educational project. So I think that if you were to ask me what the strong points were, or if you want to say the major strengths that gave me a kick-start as president of the Executive Council, I think it was undoubtedly the TEIP programme, the opportunity we had to join TEIP. So much so that today, after all these years, I still feel this TEIP identity, I still feel it a lot and I think we’ve had pilot projects—we’re still having them; we’ve had many other projects—but our identity as a TEIP was what gave us the most from the point of view of improving as an institution.(Mário Rocha)

What sets TEIP apart? (…) I remember that, in line with TEIP, right from 2010, we built a tool here to monitor everything we did and we built all the indicators there; we built all the targets there; it’s there that our class plan is made up; it’s there that our lesson plan is operationalized; it’s there that all this is crossed with the educational project. And building this internal tool meant that we had to travel all over the country—we even went to the University of the Algarve to present the tool, but then we were also asked, through the DGE, to do an intervention in some countries at the European level. And so it was, and this brought us this particularity and opportunity to have been at various times with other experiences and this obviously enriched everything we were doing and what we are today. And the truth is that this cannot be overlooked; our learning is a whole, isn’t it? So these experiences with TEIP, that TEIP brought us other opportunities, even made us get to know other realities, then the pilot project for pedagogical innovation that made us get to know a network of people who even had the same interests as us and who sometimes even had the same difficulties that we had, and at the same time it also gave us the chance to share several things and experiences that made us much better.(Mário Rocha)

3.5. The Pedagogical Innovation Pilot Project (PPIP)

The innovation projects, the innovation plans and the PPIPs, yes, they were also very important because they were also built in an immersive way, in other words, very much in cooperation and collaboration and with processes of permanent questioning and reflection, when sometimes people would say to us: So, now that we’ve made all this effort and done all this work, if perhaps they don’t approve our plan, what was the point? I said, it was useful for us to understand where we were, the difficulties we had and that, perhaps, the answers we found weren’t the best; we’re going to have to go back to the drawing board to discuss and reflect again. So this process is very much one of co-construction.(Cesário Silva)

In 2016, as I’ve already said, we entered that pedagogical innovation pilot project, PPIP, now known as PPIP1, and it was another moment, which I would say was the third impactful moment, because in addition to all the experience I had previously gained from those two impactful moments, I felt that we were now being challenged to do something different. We knew perfectly well all the steps we had to take to build teaching teams, to develop processes of monitoring and pedagogical supervision, but we also had to focus a lot on what would be pure and unadulterated autonomy, pedagogical autonomy, which could even include curricular autonomy. And this was a huge challenge, to have this very broad autonomy, in which we could, as was said at the time, literally tinker with everything, the subjects, the way the subjects were organized in the curricula, the way the curricula were organized among themselves, how these subjects were interlinked, aggregated, etc. But we could even tinker with the organization of school years, the way periods were organized, the ways teachers worked with each other—we could even tinker with the way classrooms were organized. All of this gave us a completely different mentality, a completely different view of what school environments were and how we organized ourselves within a school. That third impactful moment undoubtedly brought me and my entire team a challenge, I would say, more of a challenge, so that we could see this particular autonomy and flexibility as something that was a great opportunity for us to make a difference, and not just something that was handed down from on high, as if the tutelage ordered it and we had to comply. It completely changed the way we look at education, at schools, and brought us a lot of daring, a lot of thinking outside the box, and above all it brought us this opportunity to add something to education, which until then I can’t say we hadn’t added, because the TEIP programme had already brought us a lot, but as I said earlier, a lot in the area of monitoring and supervision, and little in the area of autonomy and curricular flexibility, in terms of pedagogical methodologies. That’s what the PPIP has brought.(Mário Rocha)

3.6. Networks of Schools

Or else, as we work in a network—our school works in a network—when we leave here and go to other schools, we disseminate what we do here, like our practices, our strategies and we bring them back… There we are confronted and we participate as speakers or whatever and then we also bring the feedback here and spread the good news to our colleagues and there is always this effort of constant outings as is usual in this cluster, with our partners from PIP1, now from PIP2 and from other network schools, from Erasmus…(FG SC Cristelo)

So these experiences with TEIP, that TEIP brought us other opportunities, even made us aware of other realities, then the pedagogical innovation pilot project that made us aware of a network of people who even had the same interests as us and who sometimes even had the same difficulties that we had, and at the same time also shared several things and experiences that made us much better. And now, much more recently, with other mentoring projects between schools, which have also given us a completely different approach to what is done, both in our country and in other schools, where we have also been able to mentor other schools, which always brings added responsibility, because when you’re learning you’re absorbing everything, when you’re mentoring someone you have the responsibility of being able to pass things on to others in a well-aligned way, so that it doesn’t seem like it’s all scattered in our heads.(Mário Rocha)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SC | School cluster |

| DGE-ME | Directorate-General of Education—Ministry of Education |

| FG | Focus group |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| PAFC | Project for Autonomy and Curricular Flexibility |

| PPIP | Pedagogical Innovation Pilot Project |

| TEIP | Educational Territories of Priority Intervention |

References

- Acton, K. (2021). School leaders as change agents: Do principals have the tools they need? Management in Education, 35, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amado, J. (2014). A investigação em educação e seus paradigmas. In J. Amado (Ed.), Manual de investigação qualitativa em educação (2nd ed.). Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra. [Google Scholar]

- Bolivar, A. (2014). Melhorar os processos e os resultados educativos. O que nos ensina a investigação. In J. Machado, & J. M. Alves (Eds.), Melhorar a escola. Sucesso escolar, disciplina, motivação, direção de escolas e políticas educativas (pp. 107–121). Universidade Católica Editora. [Google Scholar]

- Bolívar, A. (2019). Una dirección escolar con capacidad de liderazgo pedagógico. Editoral Arco/Libros-La Muralla. [Google Scholar]

- Bolívar-Botía, A. (2022). Profissão-professor: O itinerário profissional e a construção da escola. EDUSC. [Google Scholar]

- Bolívar-Botía, A., & Segovia, J. D. (2019). La investigación (auto)biográfica en educación. Ediciones Octaedro. [Google Scholar]

- Bolívar-Botía, A., & Segovia, J. D. (2024). Comunidades de práctica profesional y mejora de los aprendizajes. Editorial Graó. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, C. A., & Borko, H. (1992). Becoming a mathematics teacher. In D. A. Grouws (Ed.), Handbook of research on mathematics teachinh and learning (pp. 209–239). Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Campo, A., & Campo, E. (2017). Las tareas de la dirección y los estándares profesionales. Organización y Gestión Educativa, 25(2), I–XII. [Google Scholar]

- Day, C., & Sammons, P. (2013). Successful leadership: A review of the international literature. CfBT Education Trust. [Google Scholar]

- Day, C., Sammons, P., Hopkins, D., Harris, A., Leithwood, K., Gu, Q., Brown, E., Ahtaridou, E., & Kington, A. (2009). The impact of school leadership on pupil outcomes. Final report. DCFS. [Google Scholar]

- Desmarais, D. (2010). El enfoque biográfico. Cuestiones Pedagógicas. Revista De Ciencias De La Educación, (20), 27–54. Available online: https://revistascientificas.us.es/index.php/Cuestiones-Pedagogicas/article/view/9891 (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Dewey, J. (1933). How we think. D.C. Heath and Co. [Google Scholar]

- Esteves, M. (2006). Análise de conteúdo. In J. Á. d. Lima, & J. A. E. Pacheco (Eds.), Fazer investigação: Contributos para a elaboração de dissertações e teses (pp. 105–126). Porto Editora. [Google Scholar]

- Fullan, M. G. (1991). The new meaning of education change. Cassel. [Google Scholar]

- Gabinete do Secretário de Estado da Educação. (2017). Despacho n.° 3721/2017, de 3 de maio. Diário da República n.° 85/2017, Série II de 2017-05-03, páginas 8324–8325. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/despacho/3721-2017-106958832 (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Goleman, D., Boyatzis, R., & McKee, A. (2003). Os novos líderes. A inteligência emocional das organizações. Gradiva. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales, M., Garza, T., & Leon-Zaragoza, E. (2024). Generating innovative ideas for school improvement: An examination of school principals. Education Sciences, 14, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodson, I., Antikainen, A., Sikes, P., & Andrews, M. (2017). International handbook on narrative and life history. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hallinger, P. (2018). Bringing context out of the shadows of leadership. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 46, 5–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves, A. (1994). Changing teachers, changing times—Teachers’ work and culture in the postmodern age. Cassel. [Google Scholar]

- Leithwood, K., Day, C., Sammons, P., Harris, A., & Hopkins, D. (2006). Successful school leadership: What it is and how it influences pupil learning. CfBT Education Trust. [Google Scholar]

- Leithwood, K., Harris, A., & Hopkins, D. (2008). Seven strong claims about successful school leadership. School Leadership & Management, 28(1), 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K., Seashore, L. K., Anderson, S., & Wahlstrom, K. (2004). How leadership influences student learning: A review of research for the Learning from Leadership Project. Wallace Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X., Shen, J., Reeves, P., Wu, H., Roberts, L., Zheng, Y., & Chen, Q. (2024). Effects of the “high impact leadership for school renewal” project on principal leadership, school leadership, and student achievement. Education Science, 14(6), 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzano, R., Waters, T., & McNulty, B. (2001). School leadership that works. ASCD. [Google Scholar]

- Ministério da Educação. (1996). Despacho n.° 147-B/ME/1996, de 1 de agosto. Diário da República n.° 177/1996, Série II de 1996-08-01. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/despacho/147-b-1996-1863460 (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Ministério da Educação. (1998). Decreto-Lei n.° 115-A/1998, de 4 de maio. Diário da República n.° 102/1998, 1° Suplemento, Série I-A de 1998-05-04, páginas 1988-(2) a 1988-(15). Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/decreto-lei/115-a-1998-155636 (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Ministério da Educação. (2001). Decreto-Lei n.° 6/2001, de 18 de janeiro. Diário da República n.° 15/2001, Série I-A de 2001-01-18, páginas 258–265. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/decreto-lei/6-2001-338986 (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Ministério da Educação. (2004). Decreto-Lei n.° 74/2004 de 26 de março. Diário da República n.° 73/2004, Série I-A de 2004-03-26, páginas 1931–1942. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/decreto-lei/74-2004-210801 (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Ministério da Educação. (2008a). Decreto-Lei n.° 3/2008, de 7 de janeiro. Diário da República n.° 4/2008, Série I de 2008-01-07, páginas 154–164. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/decreto-lei/3-2008-386871 (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Ministério da Educação. (2008b). Decreto-Lei n.° 75/2008, de 22 de abril. Diário da República n.° 79/2008, Série I de 2008-04-22, páginas 2341–2356. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/decreto-lei/75-2008-249866 (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Ministério da Educação. (2019). Portaria n.° 181/2019, de 11 de junho. Diário da República n.° 111/2019, Série I de 2019-06-11, páginas 2954–2957. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/portaria/181-2019-122541299 (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Ministério da Educação e Ciência. (2012). Decreto-Lei n.° 137/2012, de 2 de julho. Diário da República n.° 126/2012, Série I de 2012-07-02, páginas 3340–3364. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/decreto-lei/137-2012-178527 (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Morgado, J. C. (2012). O estudo de caso na investigação em educação. De Facto Editores. [Google Scholar]

- Nóvoa, A. (2022). Escola e professores: Proteger, transformar, valorizar. Salvador da Baía. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2011). Improving school leadership policy and practice. pointers for policy development. [Google Scholar]

- Pina, R., Cabral, I., & Alves, J. M. (2015). Principal’s leadership on students’ outcomes. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 197, 949–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popkewitzs, T. (1988). Los paradigmas en la ciencia de la educación: Sus significados y lafinalidad de la teoría. In T. Popkewitzs (Ed.), Paradigma e ideología en investigación educativa (pp. 61–88). Mondadori Espanã, S.A. Available online: https://pt.scribd.com/document/111141714/Popkewitz-Paradigma-e-ideologia-en-investigacion-educativa (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- PORDATA. (2025). Early school leaving rate. Available online: https://www.pordata.pt/pt/estatisticas/educacao/qualificacoes-da-populacao/taxa-de-abandono-escolar-precoce-por-sexo?_gl=1*1f7ha81*_up*MQ..*_ga*NDExMzA4NTcxLjE3NDkxNzAxNTA.*_ga_HL9EXBCVBZ*czE3NDkxNzAxNTAkbzEkZzAkdDE3NDkxNzAxNTAkajYwJGwwJGgw (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Presidência do Conselho de Ministros. (2018a). Decreto-Lei n.° 54/2018, de 6 de julho. Diário da República n.° 129/2018, Série I de 2018-07-06, páginas 2918–2928. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/decreto-lei/54-2018-115652961 (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Presidência do Conselho de Ministros. (2018b). Decreto-Lei n.° 55/2018, de 6 de julho. Diário da República n.° 129/2018, Série I de 2018-07-06, páginas 2928–2943. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/decreto-lei/55-2018-115652962 (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Schow, D. A. (1983). The reflective practioner: How professionals think in action. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Schön, D. A. (1997). Formar professores como profissionais reflexivos. In A. Nóvoa (Ed.), Os professores e a sua Formação (pp. 77–91). Publicações D. Quixote. [Google Scholar]

- Serrazina, L. (1999). Desenvolvimento Profissional de Professores: Contributos para reflexão. IX Seminário da Investigação em Educação Matemática. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, J. M. (2010). Líderes e lideranças escolares em escolas portuguesas: Protagonistas, práticas e impactos. Fundação Manuel Leão. [Google Scholar]

- Stoll, L., & Louis, K. (2007). Professional learning communities: Divergence, depth and dilemmas. Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Trindade, R., & Cosme, A. (2024). Escola e conhecimento: O vínculo incontornável. Porto Editora. [Google Scholar]

- Vala, J. (1999). Análise de conteúdo. In A. S. Silva, & J. M. Pinto (Eds.), Metodologia das Ciências Sociais (pp. 101–128). Edições Afrontamento. [Google Scholar]

- Weick, K. E. (1995). Sensemaking in organizations. Sage publications. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein, J., & Simielli, L. (2022). Liderança escolar: Diretores como fatores-chave para a transformação da educação no Brasil. NESCO. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ferreira, D.; Trindade, R.; Bolívar, A. School Leadership and the Professional Development of Principals in Inclusive and Innovative Schools: The Portuguese Example. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1117. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091117

Ferreira D, Trindade R, Bolívar A. School Leadership and the Professional Development of Principals in Inclusive and Innovative Schools: The Portuguese Example. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1117. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091117

Chicago/Turabian StyleFerreira, Daniela, Rui Trindade, and Antonio Bolívar. 2025. "School Leadership and the Professional Development of Principals in Inclusive and Innovative Schools: The Portuguese Example" Education Sciences 15, no. 9: 1117. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091117

APA StyleFerreira, D., Trindade, R., & Bolívar, A. (2025). School Leadership and the Professional Development of Principals in Inclusive and Innovative Schools: The Portuguese Example. Education Sciences, 15(9), 1117. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091117