Abstract

Flexibility is increasingly recognized as a key competence in addressing current challenges and transitions. It is a multidimensional construct, discussed across various disciplines, encompassing cognitive, behavioral, and emotional dimensions. The European LifeComp framework offers one of the most recent and comprehensive definitions of this competence, emphasizing its role in enabling individuals to adapt to uncertainty, manage complexity, and foster transformative learning. This study investigates the assessment tools available to evaluate flexibility competence, focusing on their alignment with the LifeComp framework. A systematic literature review was conducted using the Scopus and WoS databases, based on inclusion criteria for language, publication type, disciplinary area, research topic, and target population, identifying 22 eligible articles. Following a quality assessment of the articles, a critical analysis revealed the presence of 22 tools and scales, including the actively open-minded thinking (AOT) scale, the resistance to change (RTC) scale, and the flexible thinking in learning (FTL) questionnaire. The findings show overlaps among flexibility and related constructs, such as learning agility and intellectual humility. However, most tools are context-specific and fail to address the multidimensional nature of flexibility competence. Future research should prioritize the development of comprehensive instruments to support educational initiatives, policy development, and professional training.

1. Introduction

Lifelong learning policies and adult education are rooted in international competence frameworks (OECD, 2019; European Commission, 2018). The success of competence-based education can likely be attributed to the economic value that education has acquired in knowledge societies (Schultz, 1963), as well as the increasing need to assess and compare educational outcomes across countries (OECD, 2024, 2023; Kankaraš & Suarez-Alvarez, 2019) to foster innovation and promote sustainable development through a just, inclusive, digital, and green transition (Montanari et al., 2023; European Commission, 2018; UNESCO, 2017; UN, 2015). On the one hand, the emphasis on competence-based education is closely linked to employment rate, professional training, economic growth, and enhancement of global competitiveness. Therefore, some scholars conceptualize competence from a neoliberal and behaviorist perspective, defining it as an individual characteristic associated with high performance (Boyatzis, 2008; Schultz, 1963). On the other hand, competence-based education aims to move beyond traditional knowledge transmission methods by integrating innovative approaches based on experience, attitude, and reflection (Margiotta, 2015; Mezirow, 1991; Dewey, 1915). From this transformative perspective, competence is understood as the capacity of individuals to effectively mobilize and coordinate their resources in specific contexts (Le Boterf, 2008), thereby achieving their functioning and integral wellbeing (M. Costa, 2019; Sen, 1985).

In the literature, competence is a complex construct without a common theoretical framework. Furthermore, there are three different terms, sometimes used interchangeably, “competence”, “competency”, and “capability” (Schneider, 2019). While competence often refers to a broader concept, competency is domain-specific, including a measurable set of personal characteristics that facilitate superior performance (Boyatzis, 2008). On the other hand, according to the capability approach, the term “capability” emphasizes the substantive freedom to achieve valuable goals for the individual (Sen, 1985; Nussbaum, 2011). In this paper, the term “competence” is used to maintain a broader and more general outlook.

One of the most influential competence frameworks was developed by the OECD’s Definition and Selection of Competencies (DeSeCo) project, aiming to prepare young people and adults for life’s challenges. The OECD proposed an external definition because it “is the demand, task, or activity which defines the internal structure of a competence, including the interrelated attitudes, values, knowledge, and skills that together make effective action possible” (OECD, 2005, p. 5). In this view, each competence exists on a continuum, including measurable competencies ranging in scale from low to high, detecting a sufficient or non-sufficient level of competence for a particular purpose. Building on the DeSeCo framework, the OECD Learning Framework 2030 defines core skills, knowledge, and attitudes and values that provide a basis for developing student agency and transformative competencies (OECD, 2019). These three competencies empower people as agents for generating alternative scenarios and individual and societal wellbeing. However, they are quite general: creating new value, reconciling tensions and dilemmas, and taking responsibility.

The main topic of this paper is flexibility competence, a critical component in the current era. Flexibility facilitates the integration of disparate ideas, transcending the limitations of hyper-specialized and siloed knowledge. This competence fosters greater interconnection between disciplines and areas of expertise that can be integrated into systemic, creative, and innovative ways to understand wicked problems, generate alternative scenarios and solutions, and support integrated problem-solving and the management of contemporary challenges. Citizens and workers will need to continually acquire new knowledge and skills throughout their life, and this requires flexibility and a positive attitude towards lifelong learning and curiosity (OECD, 2019).

Flexibility competence fosters personal development and enhances both intra- and intergenerational adaptability, which are fundamental components of the sustainable transition. In fact, flexibility empowers the development of alternative scenarios in response to the ecological crisis and the adoption of innovative and creative solutions. Furthermore, flexibility is multidimensional and enables the transformation of interaction, experiences, and habits of mind, allowing transformative learning oriented toward long-term change (Mezirow, 1991; Dewey, 1915). Thus, flexibility seems crucial in enabling people to adapt to uncertainty, manage complexity, and foster transformative learning, coping with indecision and anxiety (Caena, 2019).

In the OECD framework, flexibility is a key construct associated with the transformative competency “reconciling tensions and dilemmas”. However, it especially refers to its cognitive dimension. According to the OECD framework (2019), learners need cognitive flexibility and perspective-taking skills to integrate different points of view. Reconciling tensions and dilemmas also requires empathy and respect towards others who hold different views, creativity, problem-solving skills, and skills in conflict resolution. All these components are strictly related to flexibility, integrating its cognitive, behavioral, and emotional dimensions. For instance, flexibility is crucial in navigating intercultural and globalized contexts, enabling individuals to adapt to multicultural environments, work effectively in international teams, and manage diplomatic relations between countries by fostering mutual understanding. Additionally, flexibility plays a significant role in reducing social polarization by promoting dialogue and understanding among groups with differing opinions, encouraging the consideration of alternative perspectives, and facilitating compromises in conflict situations.

In contrast to the OECD framework, the European competence framework encompasses all dimensions of flexibility competence, providing an integrated perspective that complements the OECD approach. This perspective offers valuable insights into the development and assessment of flexibility competence, as explored in the section Flexibility Competence in the European LifeComp Framework.

1.1. The European Competence Frameworks

According to the European Commission (2018), competence is briefly described as an integrated set of knowledge, skills, and attitudes. Despite some critics (Schneider, 2019), this integrated definition includes several dimensions of competence, such as ability (actions, tasks, and roles performed according to expected standards), disposition (observational attitude, learnable, contextualized, and cognitive), integration of resources (Le Boterf, 2008), and relation among competences, the completion of tasks, and their outcomes. The integrated perspective of the European competence frameworks involves the risk of oversimplifying and reducing competences to a list of fragmented descriptors. However, their simplicity makes them easier to use, disseminate, and operationalize into measurement indicators.

In 2018, the Council of the European Union adopted the revised Recommendation on Key Competences for Lifelong Learning. These competences include literacy, multilingual, STEM, and digital competences, as well as more transversal and cross-disciplinary ones, including personal, social, and learning to learn competences. These guidelines informed the subsequent development of several competence frameworks, i.e., DigComp (Vuorikari et al., 2022), EntreComp (Bacigalupo et al., 2016), LifeComp (Sala et al., 2020), and GreenComp (Bianchi et al., 2022).

Despite the consistency of the European recommendation and shared guidelines, the risks associated with the subsequent frameworks stem from their development based on disparate epistemological approaches. For instance, the EntreComp framework aligns more closely with a neoliberal and behaviorist perspective, whereas the DigComp framework adopts a more technical orientation, and the LifeComp framework emphasizes a psychological perspective, as well as systems theory and socio-emotional and intercultural studies (Caena, 2019). LifeComp focuses on life skills, including personal, interpersonal, and cognitive and meta-cognitive skills, such as critical thinking (WHO, 1997). However, other models related to personal, social, and learning to learn competences exist (Caena, 2019). For instance, soft skills contrast with hard, technical skills, and non-cognitive skills are distinguished from cognitive skills. Another example is the OECD framework of social and emotional learning (SEL). Key references for this framework are personality traits according to the Big Five classification and Goleman’s Emotional Intelligence Theory (OECD, 2018); thus, the psychological emphasis is even more evident than in LifeComp.

According to the European LifeComp framework, life skills are transversal competences essential for all citizens to become agents of their learning, not only for psychological, cognitive, or professional development but for their whole life paths, as designers of alternative landscapes (Sala et al., 2020). These competences are imperative for effectively addressing contemporary super-complex challenges, also called wicked problems. Furthermore, it is evident that artificial intelligence and emerging technologies are incapable of replacing them. Consequently, this set of skills can be regarded as pivotal in shaping future professional landscapes (WEF, 2025).

The European LifeComp framework offers a comprehensive conceptual model for the “personal, social, and learning to learn” key competences for lifelong learning, integrating personal, interpersonal, and cognitive and meta-cognitive skills (Sala et al., 2020). They are defined as the abilities “…to reflect upon oneself, effectively manage time and information, work with others in a constructive way, remain resilient and manage one’s own learning and career. It includes the ability to cope with uncertainty and complexity, learn to learn, support one’s physical and emotional wellbeing, maintain physical and mental health, and be able to empathize and manage conflict in an inclusive and supportive context” (European Commission, 2018, p. 10).

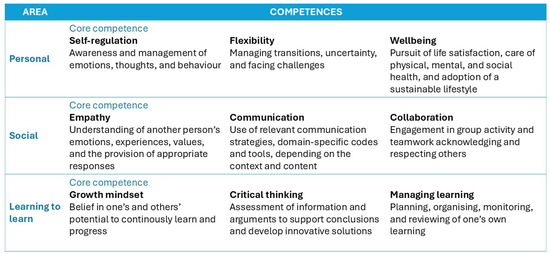

Specifically, the LifeComp framework (Figure 1) is composed of three areas: personal, social, and learning to learn. Each area comprises three competences, one of which is at the core of the other two. In turn, each competence has three complementary descriptors based on the “awareness, understanding, action” model (Sala et al., 2020). These descriptors are useful in the nine-competences operationalization of the LifeComp framework and, consequently, in the construction of indicators for their evaluation. However, it should be noted that these competences are founded upon the extant literature and frameworks that, over time, have addressed not only their description but also their evaluation. Therefore, to assess the competences presented in the LifeComp framework, first of all, it is necessary to investigate if validated assessment instruments already exist and if the competence they measure is interpreted as in the European framework. This will determine whether a new questionnaire is required or whether one already exists or requires only minor modification.

Figure 1.

The European LifeComp framework based on JRC publication (Sala et al., 2020).

Among the nine competences identified by the LifeComp framework, flexibility stands out as particularly relevant in light of the ecological, social, and technological transitions that define our time. Flexibility is not only essential for adapting to these changes, but it is a cornerstone of lifelong learning, enabling individuals to continuously acquire, update, and apply knowledge and skills in evolving contexts. Therefore, this paper focuses on this key competence.

1.2. Research Questions

Given the complexity and multidimensionality of flexibility competence and its extensive presence in the literature, it is necessary to assess whether there are existing tools capable of evaluating the three descriptors outlined in the European LifeComp framework (see the section Flexibility Competence in the European LifeComp Framework). Specifically, this study aims to identify current assessment tools and compare them to determine which could be effectively used to measure this competence through the lens of the LifeComp framework. As flexibility is a multifaceted competence, a comprehensive evaluation may benefit from mixed-methods approaches integrating both qualitative and quantitative methodologies (Creswell & Creswell, 2023). However, this paper will focus specifically on quantitative methods for competence assessment, to facilitate standardized data comparison and larger samples.

The research questions addressed in this paper are the following:

- What assessment tools aligned to flexibility competence have been developed and applied in empirical studies?

- What common or distinct aspects are measured by these instruments?

- What are the differences between the conceptualization and operationalization of flexibility competence and other current concepts, such as learning agility?

- Which of these assessment tools could be used to measure flexibility competence according to LifeComp descriptors?

To address these research questions, a comprehensive review of the state of the art on flexibility competence was conducted, followed by a systematic literature review that identified 22 tools and scales. The findings highlight overlaps among flexibility and related constructs, such as learning agility and intellectual humility. Furthermore, the Discussion Section identifies existing evaluation scales for specific flexibility domains within various contexts. These findings enabled the identification of questionnaires that only require minor adjustments to assess and compare this competence across countries.

Conducting a systematic literature review on assessment tools for flexibility competence is essential for the identification of any gaps in the literature, mapping of validated tools, and the evaluation of their alignment with the LifeComp framework. Improved assessment tools are crucial for fostering lifelong learning, supporting the development of educational policies, lifelong learning initiatives, and professional training programs aimed at developing flexibility competence, which is essential for navigating ecological, social, and technological transitions. Moreover, the review provides insights into the comparability of these tools across different cultural and professional contexts and lays the groundwork for the creation of new, more effective assessment tools where necessary.

Evaluation procedures and processes are useful to identify goals for education systems and lifelong learning (OECD, 2018). On one hand, learners can use assessment tools as reflective tools, raising awareness of their own strengths and weaknesses. On the other hand, researchers can use them to examine how pedagogical interventions may affect specific competences (Barak & Levenberg, 2016). By equipping people with flexibility competence to adapt, innovate, and embrace change, this paper ensures that flexibility competence can be accurately assessed and promoted in response to global challenges, contributing to advancing innovation and sustainable development.

2. State of the Art of Flexibility Competence

Flexibility refers to the ability to bend, vary, modify, and adapt to different conditions. It is a multidimensional capability, discussed across various disciplines. For instance, in neuroscience, behavioral flexibility is rooted primarily in cognitive activity, which relies on both functional and structural neuroplasticity (Goldberg, 2022). Flexibility, in this context, is the ability of a system to shift between functions and behaviors (Magnasco, 2022). From this perspective, flexibility is cognitive, emotional, and self-reflective (Dominguez et al., 2022), as it is essential for broad thinking, attentional control, behavioral regulation, and emotional self-regulation, particularly in uncertain situations (Roelofs et al., 2023). These various facets of flexibility appear to play a key role in metacontrol, monitoring, regulation, and response to stimuli (Eppinger et al., 2021).

According to a socio-constructivist and enactive perspective, knowledge is shaped by internal logics that can be modified according to external constraints or thresholds (Stapleton, 2021; Varela et al., 2016). This dynamic process allows individuals to select relevant factors and co-adapt within their socio-ecological system (Folke et al., 2016), facilitated by a flexible mindset. From a psychological standpoint, the cognitive dimension of flexibility could be interpreted as a rational thinking disposition. These dispositions refer to those that relate to the adequacy of belief formation and decision-making (Stanovich & Toplak, 2023).

In psychology, the flexible mindset is mainly studied as an open-minded disposition that fosters creativity, interpersonal adaptation, and conflict resolution. Some scholars have further defined open-mindedness as a moral virtue that helps individuals to avoid myside bias, a cognitive tendency to favor one’s own perspective (Stanovich & Toplak, 2023). Indeed, an organism can only define itself as autonomous and unique by differentiating itself from others and its context (Bateson, 1972). Margiotta (2015) argues that this process is inherently challenging, as encountering the unfamiliar can create cognitive dissonance by undermining the validation of one’s perceived reality. This tendency frequently leads to the perception of “the Other” as a rival, as others offer alternative narratives, experiences, and ways of thinking that may not align with our established perspectives.

At the same time, human beings are predisposed from an early age to interact with others and perceive differences as a precondition for acquiring new knowledge and learning (Bateson, 1972). These processes gradually support the understanding of the world and other people. Consequently, the evolution of language enables more complex and sophisticated interactions. This, in turn, increases the need for flexibility to accommodate and negotiate among different stimuli and perspectives. Furthermore, according to Bruner (2003), the construction of autobiographical identity involves recognition of the self and others, regulating thoughts and actions, and developing metacontrol processes, as studied in neuroscience. This view of identity as a self-reflective and socially constructed process requires a flexible mindset and, more broadly, the development of flexibility competence.

In education, flexibility has also been studied as a cognitive ability and consequently as a competence. Cognitive flexibility refers, on the one hand, to the ability to use different languages depending on specific contexts, and on the other, to the capacity to adapt one’s cognitive and learning processes across different situations, promoting new and creative ideas (Margiotta, 2015; Giunta, 2013). In other words, flexibility can be seen as the ability to interconnect and recontextualize meaningful knowledge with prior knowledge, while elements that cannot be integrated are considered irrelevant or even incongruent. This process facilitates the comprehension of complex systems and engagement in complex learning, which is necessary for managing complex knowledge and transferring it to new contexts (Giunta, 2013). As such, education should aim to foster flexible thinking, encouraging new ways of using knowledge (Margiotta, 2015).

According to Spiro et al. (1995), flexible thinking involves the establishment of appropriate habits of mind, ways of thinking, worldviews, and mindsets, grounded in past experiences. These habits are used both to organize information as it is experienced and to make sense of future knowledge. Habits of mind are dynamic. They evolve continuously in response to the complexity of the content individuals engage with, shaped by internal structuring. Therefore, flexibility enables individuals to shift their perceptual and behavioral habits through agentive–reflective practices (Dewey, 1915). With adequate flexibility, individuals are able not only to change their self-perceptions, but also to change their habits of mind through transformative learning (Stapleton, 2021; Mezirow, 1991). Conversely, humans are predisposed to establishing habits that facilitate mental economy, a process that is instrumental for future learning and accelerated decision-making processes. For instance, according to Bateson’s (1972) theory, humans are predisposed to habit acquisition. On the contrary, they experience more issues in questioning own beliefs and previous knowledge though transformative learning, even though people can potentially access it, risking increasing uncertainty and identity fragmentation.

While education aims to foster flexibility to enhance the learners’ personal development, this competence has also become a critical asset in professional and economic domains (Giunta, 2014). The current challenges brought by the labor market and Industry 4.0 and 5.0 involve constant hyperstimulation and hyperconnection, making it increasingly difficult to balance personal and professional life (M. Costa, 2019). These changes have led to an increased emphasis on new competences such as flexibility, proactivity, initiative, self-management, and creativity—all transversal competences that enhance self-efficacy as well as project management, organizational, and strategic capabilities (WEF, 2025).

The shift toward post-Fordism and lean “just-in-time” strategies requires workers to be flexible and adapt to accelerated work rhythms. However, such dynamics have often resulted in passive forms of workplace adaptation, increasing the risk of stress and job insecurity (Giunta, 2014). Today, flexibility is frequently associated with job precarity, identity fragmentation, and difficulties in maintaining work–life balance, potentially justifying unchecked competitiveness and economic growth. In response, the concept of learning agility has emerged over the last two decades, with the goal of enhancing business competitiveness (Smith & Watkins, 2024; Montanari, 2022). Being agile, in this sense, means thriving in a competitive, ever-changing environment and responding proactively and effectively to unexpected challenges. In this view, agility refers both to the ability to transfer learned lessons to new contexts and to the rapid, flexible acquisition of new knowledge.

Flexibility Competence in the European LifeComp Framework

The LifeComp framework offers one of the most recent and comprehensive definitions of flexibility competence. While this framework provides a detailed description of flexibility competence, other models, such as SEL, break it down into its various dimensions: meta-cognitive (within the compound skills), and open-mindedness, understood as a curious, tolerant, and creative attitude, while neglecting its behavioral dimension, such as adapting to change, which is included in the 21st century learning framework instead.

Flexibility competence includes multiple dimensions, such as cognitive knowledge, emotional control, openness to change, and the negotiation of multiple perspectives. According to the European framework, flexibility is included in the personal area, aimed at promoting agency and personal fulfilment, and is defined as the ability to manage uncertainty, adapt to new situations, and make necessary adjustments to face change (Sala et al., 2020). Like all LifeComp competences, flexibility is composed of three interrelated descriptors:

- Readiness to review opinions and courses of action in the face of new evidence (attitude). It implies an attitude of accepting complexity, contradictions, and a lack of clarity, demonstrating awareness that there is no single strategy which will always lead to positive outcomes, and a willingness to tackle tasks even when only incomplete information is available, to reflect on positive and negative feedback, and to modify one’s actions and personal plans where necessary.

- Understanding and adopting new ideas, approaches, tools, and actions in response to changing contexts (knowledge). It is the capacity to be open to novel ideas, tools, or ways of doing things, to negotiate different points of view, and to generate alternative solutions.

- Managing transitions in personal life, social participation, work, and learning pathways, while making conscious choices and setting goals (ability). It is the ability to learn continuously, acquire new skills, use relevant strategies for making informed choices, understand and adapt to changes, coping with indecision and anxiety, and proactively look for opportunities based on personal values, interests, skills, needs, abilities, and limitations.

According to LifeComp (see Figure 1), this competence stems from the core competence of self-regulation, which includes self-awareness, self-management, and self-efficacy and it is necessary for the competence of wellbeing, as a key driver for personal development and integral wellbeing. In fact, developing wellbeing requires the ability to navigate transitions and manage change. Furthermore, flexibility is also linked to the other LifeComp dimensions: learning to learn and social competences. The first descriptor of flexibility is promoted, for example, by the growth mindset, which fosters curiosity and a positive view of change as an opportunity for personal development. Flexibility is also linked to critical thinking, as it enables individuals to move beyond dichotomous or self-centered approaches by fostering doubt and reflection. Concerning the social dimension, flexibility promotes openness to others and the ability to embrace diversity, thereby reducing fear of the unknown. Active listening and the capacity to comprehend others’ experiences become a powerful tool for cultivating one’s own flexibility, particularly the ability to shift perspectives. A high level of personal flexibility also improves the utilization of diverse communication styles, the understanding of different points of view, and, consequently, a better quality of feedback, cooperation, conflict resolution, and cultural awareness.

In light of the transversal nature of the LifeComp framework, additional insights can be gained by examining how this competence is connected to other key European frameworks such as DigComp (Vuorikari et al., 2022) and EntreComp (Bacigalupo et al., 2016). In the case of DigComp, flexibility is both a prerequisite for managing the digital transition and a competence enhanced by the changing nature of digital environments. In the EntreComp framework, flexibility fosters the creation of new ideas, effective leadership, and the ability to manage uncertainty and risk. For instance, this competence can support inclusive leadership that values diverse perspectives and enables individuals to learn from experience, bridging theory and practice and facilitating dialogue across different domains.

The competence now called flexibility was originally referred to as adaptability in the initial version of the LifeComp (Caena, 2019). This terminology was later changed in the official 2020 release (Sala et al., 2020), without a clear explanation. In both versions, the competence is defined as the ability to accept, negotiate, and anticipate different behaviors and perspectives—essentially a process of continuous adjustment between internal processes and external stimuli, driven by the ability to reinvent oneself. Furthermore, the three descriptors of the competence remain unchanged between the two versions (Sala et al., 2020; Caena, 2019). Given the absence of substantial changes, the shift from “adaptability” to “flexibility” may be largely linguistic. Indeed, being flexible suggests an active process of change, while adapting may imply passive adjustment or conformity to external conditions.

Today, although adaptability is no longer present in LifeComp, we can find it in GreenComp (Bianchi et al., 2022), the European framework addressing the competences needed to value our planet and protect it. Here, adaptability is defined as the ability to manage sustainable transitions in complex situations and to make long-term decisions that address today’s uncertainty and ambiguity. The description of this competence closely mirrors that of flexibility, including phrases like “to adapt to new situations and adjust in order to accommodate changes in our complex world” (Bianchi et al., 2022, p. 24). The framework also distinguishes between cognitive and behavioral adaptability and lists relevant knowledge, skills, and attitudes. Although oriented toward sustainable development, the competence shares significant overlap with flexibility—particularly with its third descriptor: the ability to manage transitions. This suggests that adaptability in GreenComp may be seen as a contextualized form of flexibility for sustainable transitions.

In contrast, Bateson’s metaphor of the equilibrist offers a powerful conceptualization of flexibility in contrast to adaptability (Bateson, 1972). Adaptability refers to the ultimate goal of maintaining dynamic balance, while flexibility is seen as the positive entropy that allows continuous bodily adjustments. He argued that any system, from biological to anthropocentric, can be described as a set of interconnected variables, each with upper and lower thresholds. When these limits are exceeded, discomfort, dysfunction, or even collapse may occur (Bateson, 1972). Within these boundaries, adaptability allows adjustment, while flexibility represents the potential for transformative change.

3. Methods

To address the research questions, a systematic literature review was conducted adapted to the PRISMA 2020 guidelines (Page et al., 2021). This method ensures a rigorous and transparent process for identifying and selecting relevant studies, thereby reducing researcher bias (Paré et al., 2015).

To identify the relevant literature, I selected two major peer-reviewed databases—Scopus and Web of Science (WoS)—due to their broad international coverage. As the field of Education is not explicitly listed in Scopus, I included related subject areas such as Social Sciences, Psychology, and Arts and Humanities.

The search strings used in each database were as follows:

SCOPUS: (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“flexibility competence” OR “flexibility competency” OR “flexibility skill” OR “flexibility capability” OR “flexibility ability” OR “flexible competence” OR “flexible competency” OR “flexible skill” OR “flexible capability” OR “flexible ability” OR “agile competence” OR “agile competency” OR “agile skill” OR “agile capability” OR “agile ability” OR “agility competence” OR “agility competency” OR “agility skill” OR “agility capability” OR “agility ability” OR “adaptability competence” OR “adaptability competency” OR “adaptability skill” OR “adaptability capability” OR “adaptability ability” OR “adaptive competence” OR “adaptive competency” OR “adaptive skill” OR “adaptive capability” OR “adaptive ability” OR “adaptation competence” OR “adaptation competency” OR “adaptation skill” OR “adaptation capability” OR “adaptation ability” OR “flexible thought” OR “agile thought” OR “flexible thinking” OR “agile thinking” OR “flexibility thought” OR “agility thought” OR “flexibility thinking” OR “agility thinking” OR “adaptive thought” OR “adaptive thinking” OR “adaptation thought” OR “adaptation thinking” OR “open-mindedness” OR “openmindedness” OR “open minded” OR “learning agility” OR “learning flexibility” OR “learning adaptation” OR “learning adaptability”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (evaluation OR valuation OR assessment OR measurement OR measuring OR judgment OR test))

WoS: (TS=(“flexib* competenc*” OR “flexib* skill*” OR “flexib* capabilit*” OR “flexib* abilit*” OR “agil* competenc*” OR “agil* skill*” OR “agil* capabilit*” OR “agil* abilit*” OR “adapt* competenc*” OR “adapt* skill*” OR “adapt* capabilit*” OR “adapt* abilit*” OR “flexib* thought*” OR “agil* thought*” OR “flexib* thinking” OR “agil* thinking” “adapt* thought*” OR “adapt* thinking” OR “open-mindedness” OR “openmindedness” OR “open minded” OR “learning agil-ity” OR “learning flexibility” OR “learning adapt*”) AND TS=(evaluation OR valuation OR assessment OR measurement OR measuring OR judgment OR test)) NOT (SILOID==(“PPRN”))

3.1. Data Collection

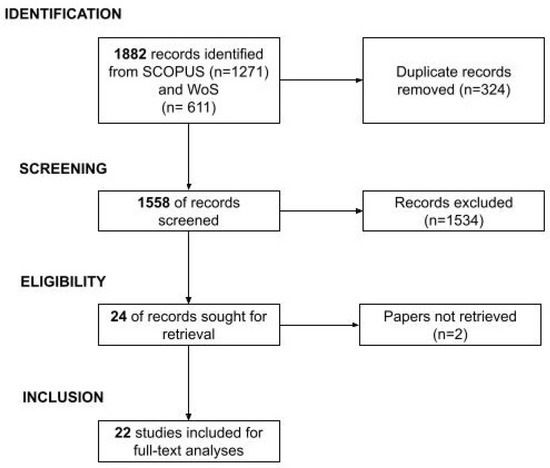

From Scopus, 1271 records were exported to a CSV file, and 611 records from WoS (last updated research conducted in January 2025). After deleting duplicates, a dataset of 1558 records were obtained and screened based on title and abstract.

In line with the research questions, the inclusion criteria for data selection are the following.

- Language: Only studies written in English, as this is the predominant language used in scientific publications across major academic databases.

- Type of Publication: Only peer-reviewed articles and reviews, as these undergo rigorous quality control and are generally more reliable sources of scientific knowledge.

- Disciplinary Focus: Studies related to the field of education, as this review focuses on flexibility as a personal competence. Although flexibility is a transdisciplinary concept, I prioritized its educational dimensions and assessment, in line with the European LifeComp framework. Consequently, studies based on personality inventories was excluded, such as the Big Five Inventory (P. T. Costa & McCrae, 1992) and the Multicultural Personality Questionnaire (Figueroa & Hofhuis, 2024; Van der Zee & Van Oudenhoven, 2001), which focus on broader personality traits rather than educational competences.

- Research Topic: Empirical studies or literature reviews that evaluated competences related to flexibility using quantitative methods. Studies whose primary aim was the validation of assessment tools measuring flexibility-related competences were also included.

- Target Population: Studies focusing on individuals aged 18 and over. Given that flexibility is a transversal competence relevant across the lifespan, the review aimed to identify questionnaires applicable in a variety of contexts. Studies focusing exclusively on child development, school and university performance, or specific professional roles (e.g., leadership) were excluded. Furthermore, the Career Adapt-Abilities Scale (Marques et al., 2024) was not considered, as it assesses dimensions related to vocational readiness, namely concern (preparing for future career tasks), control (taking responsibility for career development), curiosity (exploring possible future selves and career opportunities), and confidence (belief in one’s ability to solve problems and succeed).

Following the screening, 1534 articles were excluded, while 24 were retained for full-text reading, 2 of which could not be retrieved (Figure 2). These 22 final papers (see Appendix A) were read in full and coded to answer the research questions.

Figure 2.

Selection of sources adapted on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) structure.

3.2. Data Analyses

A critical analysis was conducted, focusing on comparing the assessment tools and their constituent categories with the indicators of flexibility competence outlined in the LifeComp framework. A critical review highlights inconsistencies in the literature and provides constructive insights to guide future research (Paré et al., 2015).

The final dataset included two literature reviews (Smith & Watkins, 2024; Ehrlich & Lee, 1969). An analysis of the annual scientific production shows an increasing interest in this competence area, with nearly half of the identified publications appearing in 2024. The earliest identified publication dates back to 1969 and examines the evaluation of dogmatism and resistance to change (Ehrlich & Lee, 1969), demonstrating that interest in this topic is not recent, even though the studies cited have not been replicated or extended with comprehensive evaluations. Notably, earlier studies primarily targeted children or university performance. Research explicitly addressing flexibility in adult education began to emerge after 2016 (Sirota & Juanchich, 2018; Barak & Levenberg, 2016).

In terms of geographical distribution, most studies were conducted in English-speaking countries, particularly the U.S.A. and the UK. Only 10 papers also included data from other countries, although some tools—such as AOT—have been translated into other languages. The choice to include English-language publications, combined with the tendency of the selected databases to prioritize English sources, may have influenced this distribution.

4. Results

The findings from the analysis are summarized in the tables below, which present the assessment scales and questionnaires related to the evaluation of flexibility. A total of 22 tools were selected because their categories overlap, to some extent, with the flexibility competence descriptors of the LifeComp framework. Among the articles analyzed, only one specific tool measures adaptability: I-ADAPT (Ployhart & Bliese, 2006). However, this tool will not be discussed further, as it is based on personality traits.

A close connection emerged between curiosity and openness to new experiences and personal development (Kashdan et al., 2020). However, curiosity is included among the descriptors of the growth mindset in the LifeComp framework. For this reason, articles focusing on curiosity assessments were excluded from eligible studies. Consequently, tools related to curiosity, such as the Curiosity and Exploration Inventory II (Krumrei-Mancuso et al., 2020) and the Epistemic Curiosity Scale (Newton et al., 2024), were not included in the analysis.

Similarly, the Social Vigilantism Scale was not included in the analysis (Krumrei-Mancuso et al., 2020). This scale measures the ability to evaluate whether the information one possesses is false and the tendency to consider others’ opinions as inferior to one’s own. Upon analyzing the items, some appear to align, at least partially, with the opposite of an open mindset (Saucier & Webster, 2010). For example, items such as “If everyone saw things the way that I do, the world would be a better place” suggest a rigid perspective. However, other items, such as “It frustrates me that many people fail to consider the finer points of an issue when they take a side” and “I often feel that other people do not base their opinions on good evidence”, are less directly related to open mindset and flexible thinking. Therefore, this scale evaluates a construct distinct from flexibility competence and flexible thinking.

Another construct that could be connected to flexibility competence is epistemic sophistication. This construct is based on a common approach that measures epistemic beliefs by assessing the degree of absolute and multiplicity of beliefs (Mustața et al., 2023; Peter et al., 2016). In other words, the Epistemic Sophistication Questionnaire evaluates individual conceptions about the nature of knowledge and the process of knowing based on the following categories:

- Certainty of Knowledge: Beliefs about the stability or tentativeness of knowledge.

- Simplicity of Knowledge: Beliefs about the complexity or texture of knowledge.

- Source of Knowledge: Beliefs about where knowledge originates.

- Justification of Knowing: Beliefs about how knowledge can be evaluated.

The conception of knowledge as a certain and simple topic could negatively impact flexibility and lead to less flexible thinking. However, this questionnaire does not specifically assess the competence examined in this paper.

Comprehensive Assessment of Rational Thinking (CART) (Stanovich & Toplak, 2024) is another tool that does not align with flexibility competence. Although it includes the AOT scale (which will be discussed later), CART primarily focuses on probabilistic, statistical, and scientific reasoning, risk knowledge, financial literacy, argument evaluation, cognitive abilities based on analogy and vocabulary, superstitious thinking, conspiracy beliefs, and trust in intuitive impressions. For this reason, it was excluded from the analysis.

Similarly, the Need for Cognition (NFC) scale (Newton et al., 2024; Marin et al., 2024; Mustața et al., 2023; Krumrei-Mancuso et al., 2020) does not overlap with flexibility competence. This scale measures the tendency to engage in and enjoy effortful cognitive activity (Cacioppo & Petty, 1982). For example, individuals with a high NFC prefer complex over simple problems and enjoy taking responsibility for challenging situations. While this tendency may influence the development of a flexible thinking style, a person with a high level of flexibility competence does not necessarily find thinking enjoyable, feel excited about learning new ways to think, or enjoy tasks that involve generating new solutions to problems.

In summary, while several tools and scales were identified that are tangentially related to flexibility competence, they were excluded from this analysis because they do not directly assess the main topic of this paper.

Table 1 shows the most frequently cited evaluation tool: the actively open-minded thinking (AOT) scale. This scale assesses open-minded thinking, understood as a disposition toward rational thinking. In the literature, several versions of the tool can be found, including the original version, Baron’s shortened version (Baron, 2019), and a 7-item version (Kossowska et al., 2023). The scale has been used in various contexts, such as workplace, technological, and academic settings, involving graduates, non-graduates, and teachers. Furthermore, open-mindedness has been studied in relation to several constructs, including creativity, wisdom, critical and reflective thinking, intellectual humility, decision-making, sense-making, and problem-solving (Stanovich & Toplak, 2024).

Table 1.

Open-mindedness evaluation.

The scale has also been translated into several languages, such as Dutch, Turkish, Greek, and Arabic (Janssen et al., 2020). However, there is criticism regarding its internal validity, and it remains unclear whether it is a unidimensional or multidimensional scale (Janssen et al., 2020). For this reason, Table 1 does not include specific categories but instead references constructs such as flexible thinking, openness to ideas, openness to values, absolutism, dogmatism, and categorical thinking, which are related to dualistic thinking, such as right and wrong.

Three tools were identified that measure the cognitive dimension of flexibility (Table 2). The cognitive flexibility scale focuses on cognitive flexibility but also evaluates aspects such as the willingness to be flexible and adapt to situations. This scale assumes that individuals must first be cognitively flexible before they can display flexibility (Martin & Rubin, 1995). In fact, not all items strictly refer to the cognitive dimension. For instance, the following items are, respectively, linked to behavioral adaptation, willingness to change, and self-efficacy: “In any given situation, I am able to act appropriately”; “I am willing to listen and consider alternatives for handling a problem”; “I have the self-confidence necessary to try different ways of behaving”.

Table 2.

Cognitive flexibility tools.

The flexible thinking in learning (FTL) questionnaire evaluates cognitive flexibility in the context of learning specifically linked to technology acceptance (Barak & Levenberg, 2016). The third tool assesses various thinking styles, including AOT and close-minded thinking (CMT), which reflect the extent to which individuals perceive truth in black-and-white terms (Newton et al., 2024). Additionally, the questionnaire measures two other thinking styles: PIT and PET. It is important to note that the AOT, CMT, PIT, and PET scales should not be considered as parallel measures operating on a single continuum. Instead, these scales represent distinct types of thinking styles, even though the subscales are moderately intercorrelated.

Resistance to change (RTC) and dogmatism were identified as constructs opposite to cognitive flexibility (Table 3). For instance, according to Barak and Levenberg (2016), cognitive flexibility can be defined as the opposite of RTC as measured by the RTC scale (Oreg, 2003). This scale originates in the field of psychology, but it builds upon the notion that resistance to change is a modifiable personal disposition rather than a personality trait. This scale has been validated in various countries, including Italy, to measure the individual’s tendency to resist change (Bobbio et al., 2009). The RTC scale is structured into four categories: preference for routine, emotional reactions to change, short-term focus, and cognitive rigidity. In this case, both behavioral flexibility, through the preference for or avoidance of routine, and the emotional dimension connected to change are analyzed. Another scale, the dogmatism scale, measures rigid belief in one’s opinions and unwillingness to consider other perspectives (Altemeyer, 2002). In fact, individuals with high levels of dogmatism tend to rely on pre-existing beliefs. Furthermore, dogmatism has been associated with a decreased ability to engage in rational thinking and problem-solving (Mustața et al., 2023).

Table 3.

Resistance to change and dogmatism.

Table 4 presents 10 questionnaires that measure learning agility and 1 that evaluates the agile mindset (Imjai et al., 2024). Learning agility is often studied in professional contexts, particularly in leadership and employee development, which may limit their applicability to other domains. Indeed, the following scales are specifically designed for two distinct populations: the Leadership Learning Agility Scale for leaders and the Employee Learning Agility Measure for employees. In contrast, the IDLAW scale (Milani et al., 2024) is a more versatile tool that can be applied to both leaders and employees and also to broader populations such as students or individuals outside of professional environments (Milani et al., 2024). This scale includes two key dimensions:

Table 4.

Agile mindset and learning agility.

- Mastery orientation, which promotes the development of new skills for continuous improvement, similar to the growth mindset in the LifeComp framework.

- Adaptive orientation, which aligns with the definition of flexibility competence in the LifeComp framework, emphasizing the ability to adjust to new situations and challenges.

Most of the questionnaires are based on the conceptualization by Lombardo and Eichinger, which emphasizes self-awareness, as well as mental, people, change, and results agility (Smith & Watkins, 2024). While self-awareness and people agility can be linked to other competences within the LifeComp framework—specifically self-regulation and the social dimension of LifeComp—the other three dimensions relate to the ability to manage complex situations, navigate change, and achieve results in uncertain contexts. This highlights the performance-oriented and results-driven nature of the agility construct. Similar to these five categories are those developed in the TALENTx7 framework, which more specifically includes a cognitive dimension of critical thinking, an interpersonal competence for accepting external feedback, and the ability to remain curious and learn new ideas. On the other hand, Burke’s definition builds on de Rue’s work, which maintains a performance-oriented character but explicitly states that the construct of learning agility comprises both flexibility and speed, as well as reflection on learning processes. This aligns with the “learning to learn” dimension in the LifeComp framework and includes social aspects of collaboration and entrepreneurial skills, such as information-seeking (see EntreComp, Bacigalupo et al., 2016).

A broader concept of agility is the agile mindset, which also originates in professional contexts. The agile mindset encourages individuals not only to embrace change but also to adapt more quickly, like Burke’s definition and de Rue’s work. A key aspect of this construct is the emphasis on continuous learning, which is necessary to adapt to change and underscores the close connection between “learning to learn” and flexibility.

In summary, the connection between flexibility competence, learning agility, and the agile mindset is evident. However, the latter constructs also encompass other types of competences, primarily social and performance/entrepreneurial skills. In fact, the conceptualization of learning agility often emphasizes performance-oriented outcomes, such as achieving results in uncertain contexts, which may not fully align with the transversal nature of the LifeComp framework. Additionally, there has been a proliferation of proprietary and copyright-protected diagnostic tools with limited accessibility (e.g., Choices Architect® by Lombardo & Eichinger; viaEDGE™; TALENTx7). This issue poses challenges in terms of construct clarity and the availability of valid measures.

Table 5 presents other scales that are specific to the workplace and, therefore, not extendable to other contexts, such as university students. For example, the employee competencies scale includes, in addition to social, self-regulation, and entrepreneurial competencies (see Ethical and Sustainable Thinking in EntreComp Framework), the change competency which appears to correspond to flexibility competence. This competency is understood primarily in a behavioral rather than cognitive sense, referring to the ability to identify and implement adjustments or complete changes in various areas, such as interpersonal relationships, the use of technologies, and modifications to one’s tasks (Otoo, 2024). The other scale specifically evaluates work flexibility, focusing on work–life balance rather than general flexibility competence. In this scale, flexibility is broken down into skills, availability, concerns, and social pressures. As such, it does not specifically address cognitive flexibility but rather emphasizes behavioral and attitudinal aspects.

Table 5.

Workplace-specific scales.

Table 6 analyzes three tools that measure intellectual humility, a construct closely related to flexibility competence. Intellectual humility focuses on openness to revising one’s viewpoint, respecting other perspectives, facing intellectual disagreement, and an appropriate discomfort with one’s own limitations (Beebe & Matheson, 2023). Another component of this concept is less overconfidence in estimates and predictions (Krumrei-Mancuso et al., 2020). According to Beebe and Matheson (2023), intellectual humility is a virtue that supports the acquisition of new knowledge by encouraging individuals to spend more time and effort engaging in cognitive exploration, considering alternative perspectives, and learning collaboratively. Consistent with this theory, this concept has been associated with reflective thinking, the need for cognition, intellectual curiosity, intellectual openness, and open-minded thinking. These findings suggest that this construct is predictive of greater openness to learning about opposing perspectives and adapting to new information.

Table 6.

Humility scales.

5. Discussion

The findings of this study provide a comprehensive overview of the tools and scales used to evaluate flexibility competence and related constructs. The previous section identified the assessment tools aligned with flexibility competence applied in empirical studies, highlighting the categories and aspects they measure, in accordance with first and second research questions. While 22 tools were identified, only a few directly assess flexibility competence as described in the European LifeComp framework (Sala et al., 2020). This highlights the complexity of operationalizing flexibility competence and its correlation with diverse constructs.

One key insight from the analysis is the overlap between flexibility competence and other constructs, such as curiosity (Kashdan et al., 2020), epistemic sophistication (Mustața et al., 2023), learning agility (Smith & Watkins, 2024), and intellectual humility (Krumrei-Mancuso et al., 2020). These constructs share common dimensions with flexibility, such as openness to new experiences, adaptability, and reflective thinking. However, they also include unique elements that extend beyond the categories of flexibility competence. For instance, epistemic sophistication, which evaluates beliefs about the nature of knowledge, provides valuable insights into cognitive flexibility but does not directly assess the behavioral or emotional dimensions of flexibility competence (Mustața et al., 2023). Furthermore, curiosity is closely linked to openness to new experiences, but it is categorized under the growth mindset in the LifeComp framework (Sala et al., 2020). Therefore, the exclusion of tools like the Curiosity and Exploration Inventory II (Krumrei-Mancuso et al., 2020) and the Epistemic Curiosity Scale (Newton et al., 2024) underscores the importance of distinguishing flexibility competence from related but distinct constructs.

On the other hand, humility scales are included in the analysis, revealing a strong connection to flexibility competence (Krumrei-Mancuso et al., 2020). Intellectual humility emphasizes openness to revising one’s viewpoint, respecting other perspectives, and engaging in reflective thinking. However, while flexibility focuses on adapting to change and managing uncertainty, intellectual humility is a trait or a virtue that emphasizes the cognitive and interpersonal competences necessary to engage with diverse viewpoints. These traits are essential in navigating intellectual disagreement and adapting to new information. This suggests that intellectual humility may complement flexibility competence, or even serve as a prerequisite, similar to the role of self-regulation in the LifeComp framework. Further studies are needed to explore this relationship in depth.

The findings also highlight the limitations of tools related to learning agility (Smith & Watkins, 2024). Most of these tools are performance-oriented and context-specific, limiting their applicability to broader populations, such as students or individuals outside of professional environments. However, learning agility emphasizes adaptability, openness to feedback, and the ability to navigate complex and uncertain environments. Thus, the connection between flexibility competence, learning agility, and the agile mindset, as well as the learning to learn competence, is evident, particularly in professional contexts. However, learning agility is often associated with speed, a characteristic not explicitly present in all definitions of the construct (Smith & Watkins, 2024). In contrast, flexibility competence is not inherently linked to speed. Dealing with complex knowledge often requires time to adapt cognitive processes to new situations, generate new ideas, or shift their perceptual and behavioral habits through agentive–reflective practices (Dewey, 1915). Indeed, scholars in fields such as behavioral economics and organizational learning stress the importance of balancing fast and slow thinking (Kahneman, 2012), as well as single- and double-loop learning (Argyris & Schön, 1996). Therefore, while learning agility is valuable in certain contexts, it may not always be optimal, as it could encourage passive adaptation rather than active, reflective engagement.

The AOT scale emerged as the most frequently cited tool for evaluating open-minded thinking, a key component of flexibility competence. Its widespread use across various contexts, including workplace, academic, and technological settings, highlights its versatility (Baron, 2024, 2019; Stanovich & Toplak, 2024; Janssen et al., 2020). However, while the AOT scale captures rational and reflective thinking, it may not fully encompass the behavioral and emotional aspects of flexibility competence, similarly to the FTL questionnaire. On the other hand, the cognitive flexibility scale offers a multidimensional approach by addressing aspects that are not strictly cognitive, even if this scale also includes items linked to communication competence such as “I can communicate an idea in many different ways” (Martin & Rubin, 1995).

The RTC scale evaluates behavioral and emotional dimensions, such as preference for routine and emotional resistance to change, as well as cognitive rigidity (Oreg, 2003). However, this tool focuses on the absence of flexibility rather than its presence. The analysis of this scale, as well as the dogmatism scale (Mustața et al., 2023), provides an interesting perspective on constructs that are conceptually opposite to flexibility competence, highlighting the barriers to flexibility. In contrast, according to Newton et al. (2024), CMT and the AOT scale should not be considered parallel scales operating on a continuum. This distinction is particularly evident when comparing CMT and flexibility competence. Flexible thinking does not merely involve avoiding rigid or binary perspectives; rather, it enables individuals to adopt divergent viewpoints and acknowledge multiple interpretations.

Many of the tools analyzed are context-specific, focusing primarily on workplace or professional environments. This emphasis reflects the relevance of flexibility competence in these settings, as reported by the World Economic Forum (WEF, 2025). Additionally, flexibility competence is often associated with achieving a better work–life balance, which is increasingly relevant in promoting decent work, as addressed by Goal 8 of the 2030 Agenda (UN, 2015). However, the narrow focus of these tools limits their applicability to broader populations and fails to capture the transversal nature of flexibility competence as envisioned in the LifeComp framework (Sala et al., 2020). Despite these limitations, such tools remain valuable for evaluating flexibility competence in specific domains. For instance, the FTL questionnaire (Barak & Levenberg, 2016) appears to be a valid tool for assessing cognitive flexibility in relation to learning, particularly in the context of technological transitions.

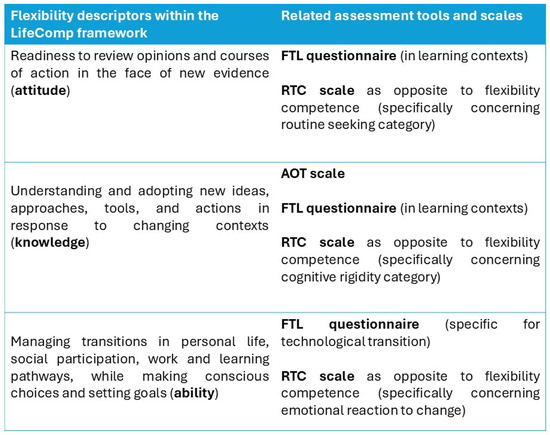

Addressing the last research question, Figure 3 summarizes the assessment tools and scales related to the specific descriptors of flexibility competence based on the LifeComp framework. The versatile AOT scale extensively evaluates the cognitive dimension of this competence, as described in the second descriptor. On the other hand, the FTL questionnaire offers a more comprehensive approach, albeit specific to learning contexts and technological transitions. Finally, the RTC scale provides a useful option for evaluating the absence of flexibility competence across all its dimensions.

Figure 3.

Overview of assessment tools and scales for evaluating flexibility competence based on the descriptors within the European LifeComp framework, including knowledge, skills, and attitudes dimensions.

Flexibility competence and its benefits for citizens: insights from the reviewed studies

From the articles analyzed, it is evident that AOT, particularly its fact-resistance dimension, is strongly associated with flexible thinking (Baron, 2019). Individuals capable of adapting beliefs, values, and opinions in light of new evidence represent this cognitive style, which contrasts with dogmatism, defined as the belief in a single correct philosophy or way of doing things (Threadgold et al., 2022). As observed by Pennycook et al. (2020), the AOT scale was originally designed to assess the perceived value of seeking evidence that might challenge one’s intuitions.

Across the studies reviewed, several benefits of the cognitive dimension of flexibility emerge as essential for citizens. For example, AOT correlates with acceptance of counterintuitive ideas, accurate evaluation of arguments, reduced susceptibility to cognitive biases, lower uncertainty aversion, and greater accuracy in factual beliefs (Baron, 2024; Marin et al., 2024; Kossowska et al., 2023; Threadgold et al., 2022). It is also positively linked to belief in human-caused climate change and global warming (Threadgold et al., 2022).

Stanovich argues that AOT reflects a “modernist mindset” shaped by historical shifts from local traditions toward science and rationality, capturing the ability to decouple from entrenched knowledge to consider conflicting evidence. However, cultural differences could emerge. For instance, Asian cultures tend to exhibit more dialectical thinking, which assesses how individuals integrate contradictions into a comprehensive perspective, potentially yielding higher AOT scores compared to the linear rationality more common in European and American contexts (Newton et al., 2024).

Based on papers analyzed, in the scientific domain, AOT underpins inquiry by guiding researchers to identify research gaps or anticipate possible criticisms before publishing their own work (Baron, 2019). However, scientific thinking should not be conflated with the mere pursuit of objectivity. A high level of scientific thinking can protect individuals from automatically aligning reasoning with prior attitudes, fostering openness to valid opposing arguments, and enabling recognition of both errors and valid points (Marin et al., 2024).

Beyond science, AOT has potential societal benefits. According to Baron (2019), it can reduce the polarization and fanaticism that often paralyze political systems and thus should function as a social norm. Given that most citizens lack the time or expertise to examine policy issues in depth, it is preferable to place trust in leaders who encourage open reflection rather than indoctrination.

According to Baron (2019), some individuals fail to notice when a statement lacks hedging expressions (e.g., “probably,” “according to some studies,” etc.). This insensitivity leads them to accept as true highly exaggerated or false statements. Consequently, even when they encounter cautious phrasing in areas they do not believe in, they attach little value to such nuance. For this reason, AOT should be understood as a “design” of thinking, including clear purposes of argumentation, a structure of testing and revising, and a rationale for why this structure is effective (Baron, 2019).

AOT is also linked to skepticism toward conspiratorial, paranormal, and religious claims. For instance, AOT was strongly associated with prior categorical changes in religious beliefs (Newton et al., 2024). Moreover, in the literature, AOT has also been linked to political liberalism. Pennycook et al. (2020) reported that AOT was positively correlated with liberal positions such as support for same-sex marriage and abortion rights. This may indicate that political conservatives—often more resistant to societal change—are also less receptive to intrapersonal belief change. However, levels of conspiracy belief were equivalent between Democrats and Republicans (Pennycook et al., 2020). Large effect sizes should therefore be interpreted cautiously, avoiding the conclusion that conservatives are inherently less open-minded. Instead, Pennycook et al. (2020) posit that belief formation among conservatives may be shaped more strongly by unexamined factors. Beebe and Matheson (2023) also found that individuals scoring higher in AOT are more conciliatory in the face of peer disagreement, although Baron (2019) notes that direct evidence for AOT’s benefits in negotiation remains limited.

Other studies concerning the cognitive flexibility scale reveal that flexibility predicts young adults’ life satisfaction in a positive and meaningful way (Yelpaze & Yakar, 2020). Empathetic and altruistic people tend to consider alternative perspectives, adapt to new situations, and seek solutions. For instance, the existing literature reported that university students with more cognitive flexibility have more life satisfaction and are less affected by stress and worrying events. In addition, women with low flexibility are more likely to experience post-traumatic stress, depression, and experiential avoidance.

In conclusion, educational environments should foster flexible competence and altruistic behaviors, as the latter enhance the cognitive dimension of flexibility. Furthermore, flexibility competence in education predicts acceptance of learning technologies and adaptation to novel instructional approaches (Barak & Levenberg, 2016). Finally, findings indicated no significant effects for learning path, gender, or age, which may suggest generalizability of data (Barak & Levenberg, 2016).

6. Conclusions

Flexibility competence fosters integral wellbeing, enables transformative learning, and generates innovative and creative solutions for alternative scenarios. According to the WEF (2025), it is one of the crucial competences for the future. The analyzed studies frequently highlight the human tendency to safeguard beliefs and identity, underscoring the key role of flexibility competence in managing change, navigating transitions, and fostering wellbeing, as described in the European LifeComp framework (Sala et al., 2020). This competence contributes to promote creativity and innovation, enhancing not only workforce adaptability but also interpersonal adaptation and conflict resolution, promoting sustainable transition. The significant growth of empirical studies identified in this paper highlights the relevance of investigating this competence. This emphasizes the need to identify existing evaluation tools facilitating standardized data comparison, educational initiative implementation, and competence development.

Improved assessment tools are essential to support educational initiatives, policy applications, and professional training programs. By providing more accurate and multidimensional evaluations of flexibility competence, these tools can help to identify specific areas for personal development, tailor interventions to individual and contextual needs, and foster lifelong learning. Furthermore, they play a critical role in equipping individuals with the competences needed to navigate complex ecological, social, and technological transitions.

This paper provided a comprehensive analysis of the tools and scales used to assess this competence. The findings revealed a growing body of empirical studies on flexibility competence and related constructs, reflecting the relevance of this competence in addressing global challenges, such as achieving a better work–life balance, promoting decent work, as well as dealing with complex knowledge and individual differences. A key insight from this research is the relevance of balancing rapid adaptability with reflective and agentive practices, particularly when addressing complex and systemic challenges, redefining the role of concepts like learning agility. Moreover, the findings also highlighted overlaps between flexibility and other related constructs, such as the virtue of intellectual humility.

Among the 22 tools analyzed in this systematic literature review, only a few directly assess flexibility descriptors as conceptualized in the European LifeComp framework, which offers one of the most recent and comprehensive definitions of this competence. For instance, the AOT scale is widely used to assess the cognitive dimension of flexibility competence, but it often neglects behavioral and emotional aspects (Baron, 2024, 2019; Stanovich & Toplak, 2024; Janssen et al., 2020). In contrast, tools like the RTC scale address behavioral and emotional dimensions, such as resistance to change and preference for routine, but focus on the absence of flexibility rather than its presence (Oreg, 2003). These findings suggest that while some validated tools exist, none fully capture the multidimensional nature of flexibility competence as defined by the LifeComp framework. Therefore, this paper emphasizes the need to adjust existing questionnaires.

The findings of the paper analyzed highlight the central role AOT as a cognitive dimension of flexibility competence (Threadgold et al., 2022; Baron, 2019). This cognitive style has been linked to several societal and individual benefits, including acceptance of counterintuitive ideas, reduced susceptibility to cognitive biases, and greater accuracy in factual beliefs (Baron, 2024; Marin et al., 2024; Kossowska et al., 2023). Moreover, AOT has potential societal benefits, such as reducing polarization and fanaticism, fostering critical thinking, and promoting open reflection in political and social contexts (Baron, 2019). These findings underscore the importance of nurturing AOT as part of flexibility competence to address global challenges and enhance societal cohesion.

In addition to AOT, the cognitive flexibility scale reveals that flexibility competence positively predicts life satisfaction, reduces stress, and enhances the ability to adapt to new situations and seek solutions (Yelpaze & Yakar, 2020). These benefits are particularly evident in educational contexts, as revealed using the FTL questionnaire (Barak & Levenberg, 2016). Furthermore, the findings suggest that flexibility competence is a transversal skill, with no significant effects related to learning path, gender, or age, indicating its generalizability across diverse populations.

In conclusion, this study highlighted the limitations of many existing tools, which are often context-specific and tailored to workplace or professional environments. This narrow focus restricts their applicability to broader populations. However, these tools could be valuable to evaluate flexibility competence in specific contexts. For example, the FTL questionnaire shows promise for assessing cognitive flexibility in educational contexts, particularly in relation to technological transitions (Barak & Levenberg, 2016).

Limitations and Future Research

One of the key challenges identified by this study is the proliferation of proprietary and copyright-protected diagnostic tools (Smith & Watkins, 2024). Limited accessibility and lack of transparency in development and validation processes pose significant barriers to adopting standardized measures for flexibility competence. Another limitation is the focus on quantitative evaluation. Mixed-methods approaches could offer a more holistic perspective by capturing the nuanced and multidimensional nature of this competence, even though they pose challenges for data comparison (Creswell & Creswell, 2023). Furthermore, only English-language literature and publications indexed in WoS and Scopus databases were selected. Despite conducting a systematic literature review, some relevant studies may have been unintentionally missed. These limitations may restrict the generalizability of the findings and highlight the need for more inclusive and diverse research approaches. Hence, future research could address this limitation by integrating additional databases and case studies to explore cross-country differences and further validate findings.

This study underscores the importance of adapting assessment tools to align with the flexibility competence, as described within the European LifeComp framework. Therefore, future research should focus on adjusting and creating comprehensive, multidimensional tools that integrate cognitive, behavioral, and emotional dimensions, while also taking into account the specific limitations of existing assessment tools. Consequently, it will be possible to conduct empirical studies on flexibility competence in its multiple dimensions rather than limiting the analysis to a single dimension. Additionally, assessment tools need to be adapted based on the context and the age of the target population. Addressing these gaps could provide a more comprehensive understanding of flexibility competence and its assessment across diverse settings.

Funding

Open Access Funding by the University of Vienna.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges colleagues from CISRE and the Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, particularly Massimiliano Costa, the supervisor of this research project, and Ines Giunta for their guidance. The author also thanks the University of Vienna and colleagues for providing support and Open-access funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AOT | Actively Open-Minded Thinking |

| CART | Comprehensive Assessment of Rational Thinking |

| CMT | Close-Minded Thinking |

| FTL | Flexible Thinking in Learning |

| NFC | Need for Cognition |

| PIT | Preference for Intuitive Thinking |

| PET | Preference for Effortful Thinking |

| RTC | Resistance to Change |

Appendix A

| Author(s) (Year) | Research Aimed and Sample | Evaluation Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Baron (2024) | Exploration of the relation among actively open-minded thinking, myside bias, and uncertainty aversion. Sample: 100 participants between 20 and 79 years old, mostly from North America. | AOT (Baron’s short version) and context-specific evaluation of myside bias and uncertainty aversion |

| Imjai et al. (2024) | Investigation of the interplay among digital literacy, agile mindset, design thinking, and management competency. Sample: 450 young accountants in Thailand. | Digital literacy Agile mindset Design thinking skill Management control competency |

| Marin et al. (2024) | Examination of the influence of attitudes and people’s level of cognitive sophistication on their fallacy evaluations and people’s acceptance of poorly justified arguments. Sample: 1325 Finns (mean age 40.2). | Thinking styles measured by the following: AOT Humility scale Cognitive reflection (CRT-2) scale (open-ended questions) Rational–experiential multimodal inventory (REIm-13) based on NFC and faith in intuition that evaluates individual’s trust in their own intuition and intuitive impressions when making decisions Scientific literacy (assessed with problems from the scientific reasoning scale) Attitudes toward hot topics |

| Milani et al. (2024) | Preliminary validation of IDWAL scale to measure individual differences in learning agility at work. Sample: 29 senior managers from Center-Eastern European countries, Italy, and Egypt. | Individual differences learning agility (IDLAW) scale |

| Newton et al. (2024) | Index development to distinguish intuitive versus analytic thinking. Sample: 413 participants for the first study (mean age 33.5) and, for the second study, 1090 participants resident in the U.S.A. (mean age 49). | 4-component thinking styles questionnaire (4-CTSQ) and references to various intuitive–analytic thinking style measures |

| Otoo (2024) | Exploration of the relationship between HR practice and employee competencies (ethical, communication, team, change, and self-competency) using organizational learning culture as a mediating variable. Sample: 828 employees of 37 healthcare institutions in Ghana (24 were internationally owned). | Human resource development practices scale Employee competencies scale Organizational learning culture scale |

| Smith and Watkins (2024) | Literature review on existing learning agility measures. No. of measures analyzed: 9. | Korn Ferry’s viaEDGE Burke learning agility inventory (LAI) TALENTx7 Leadership learning agility scale (LLAS) Employee learning agility measure Learning agility research instrument (LARI) Other different learning agility measures |

| Stanovich and Toplak (2024) | Evaluation of the associations of conspiracy beliefs through comprehensive assessment of rational thinking (CART). Sample: 721 citizens in the U.S.A. (mean age 26.6 years). | CART subtests and CART thinking disposition scales, such as AOT, deliberative thinking scale, future orientation scale, and differentiation of emotions scale |

| Tripathi and Kalia (2024) | Investigation of the influence of a supportive work environment and organizational learning culture on organizational performance with a mediation of learning agility and organizational innovation. Sample: 379 participants from ten different information technology software organizations situated in the southern part of India. | Supportive work environment based on perceived climate, perceived organizational support, peer group interactions and supervisory relationship scales Organizational learning culture based on the dimensions of a learning organization questionnaire (DLOQ) Learning agility Organizational innovation to assess readily acceptation to innovations Organizational performance to investigate organizational efficiency |