Abstract

The concept of governance has gained increasing attention across various fields of study. However, its application within the specific context of educational policies, particularly within compulsory public education, remains fragmented and underexplored. To answer the questions “How is governance conceptualized in the context of the compulsory public education system?” and “What contributions to future research emerge from this review?”, 32 peer-reviewed articles published in open-access journals between 2019 and 2023 were extracted from the Web of Science, Scopus, and ERIC databases and selected following PRISMA guidelines. Results from this systematic literature review analysis suggest a sustained yet moderate interest in the field, as evidenced by the reviewed publications, different theoretical and conceptual approaches, and research themes that illustrate different aspects of educational systems. Research gaps include the lack of a consolidated and integrated theoretical–conceptual framework on educational governance; the under-representation of specific actors, contexts, and points of view about how educational policies intentions are interpreted and enacted; insufficient critical analyses of, among others, educational leadership, digital transformation, and non-state actors’ influence in educational governance; and limited discussion of governance’s effects on educational justice, equity and quality. The main limitations relate to geographic, linguistic, and cultural biases of the analyzed studies, the exclusion of non-open-access articles, and the predominance of qualitative methodological approaches, which restrict generalizability. To address these challenges, future research should follow the adoption of interdisciplinary approaches, longitudinal and context-sensitive studies, and the use of mixed methodologies. These findings could contribute to a more informed discussion, avoiding reductionist interpretations and more open and critical perspectives on how educational governance transcends organizational and technical structures by incorporating political, ethical, and contextual dimensions that challenge the quality of educational systems.

1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Emergence and Conceptual Plurality of Governance

The concept of governance became relevant and “omnipresent” (Schmitter, 2019, p. 547) in the 1990s and has been widely debated in academic literature in various disciplines, such as public administration, political science, economics, sociology, or development studies1 (Bevir, 2011, 2012; Levi-Faur, 2012), and more recently, education. However, as Bevir states, “Each discipline sometimes acts as if it owns the word and has no need to engage with the others” (Bevir, 2011, p. 1). This perspective helps to explain why the literature on governance is so diffuse (Bevir, 2013, p. 1), with overlapping concepts and meanings, carrying out images and meanings of change, and often serving as a substitute for government (Levi-Faur, 2012). As Schmitter (2019) points out, governance can refer to the broadest definition, such as “getting things done by mobilizing collective resources,” enabling the avoidance of more controversial terms such as “the state”, “the regime”, “the rulers” or “the government,” viewed as public agents of coercion (2019, p. 548). It can also refer to a “distinctive method or mechanism for resolving conflicts and solving problems that reflects (…) characteristics that are emerging in (…) societies and economies” (Schmitter, 2019, p. 549) rooted in a novel and flexible combination of social–political interactions between actors from the state, the market, and the civil society. Therefore, some authors refer to governance as an umbrella term (Porras, 2018).

Rhodes (1996) was one of the first authors to analyze the conceptual plurality of governance, which was initially contrasted with the term “government.” According to this author (id.), the model of governance, defined as the manner, method, or system of administering a specific society, transcends central government. It brings together non-state actors, who organize themselves into networks, facilitating a continuous flow of interactions and resource exchange. This process generates various interdependencies and modifies the boundaries between the public and private sectors. In this regard, Stoker (1998) argues that the focus of governance is ultimately on creating conditions for implementing structured rules and collective action. Consequently, the results of governance are not significantly different from those of the government, suggesting that the difference lies in the processes rather than the results.

Initially associated with transformations in state action and authority (Rhodes, 1996; Jessop, 1998, 2002), governance is now designated as a complex interplay of actors, institutions, and regulatory mechanisms that exceed traditional state hierarchies. In education, it has become a key lens that helps to examine how responsibilities are distributed, how decisions are made, and how accountability is structured across multilevel systems (Ball, 2008).

In the literature, the term does not point to a unified model, a consensual theory, or static empirical uses, but reflects a plurality of interpretations, regarding conceptual variations that respond to national traditions, institutional arrangements, and ideological agendas. In this vein, scholars use different qualifiers, such as network governance, meta-governance2, digital governance, and heterarchical governance, to capture the diversity and complexity of coordination mechanisms (Kooiman, 2003; Gulson & Sellar, 2019; Kim, 2020).

In the context of compulsory public education, these conceptualizations are further complicated by the coexistence of global pressures (e.g., from OECD or UNESCO), national reforms, and local enactments. Governance arrangements in this field are thus shaped by interdependencies across levels, asymmetries of power, and competing logics of accountability, marketization, and participation (Ozga, 2009; Peruzzo et al., 2022).

As this diversity also reflects epistemological tensions and analytical fragmentation within the field of education, understanding how governance is conceptualized in compulsory education systems requires a systematic and interpretative reading of the existing literature. This is why this presents an opportunity for research.

1.2. Mapping the Contemporary Debate on Educational Governance

Due to the growing complexity of policy processes, the diversification of the actors involved, and the evolution of the state’s role in education, the idea of educational governance has gained popularity in recent decades (Gunter et al., 2014). Instead of referring to a fixed model, governance describes a flexible and dynamic collection of agreements encompassing power, control, involvement, and responsibility at various educational levels (Ball, 2012; Verger et al., 2016). The shift from government to governance underscores the reconfiguration of state responsibilities and the emergence of multi-actor, multi-scalar and hybrid forms of coordination.

In the literature, several conceptual frameworks and analytic lenses are used to address educational governance, often framed by wider political and epistemological disputes. Some studies draw on policy enactment theory to explore how policies are interpreted and recontextualized by schools and educators (Ball et al., 2012), while others engage with institutional theory (e.g., Kim & Choi, 2023), governmentality (e.g., Peruzzo et al., 2022), or multilevel governance approaches (e.g., Simkins et al., 2019; Verger et al., 2019) to account for the interaction between global, national, and local dynamics. Although these approaches provide valuable insights, they also highlight the fragmentation and plurality in the conceptualization of governance, which is often mobilized in diverse and sometimes contradictory ways (Greany, 2022; Sayed et al., 2020).

Despite growing interest in governance, in previous literature reviews, scholars have explored educational governance with diverse purposes, offering theoretical basis, analytical instruments and critical diagnosis aiming to contribute to and amplify this contemporary debate, but few systematic literature reviews have comprehensively mapped how the concept is theorized and operationalized in the context of compulsory public education. Existing reviews tend to focus on specific themes—such as accountability (Lingard et al., 2017), democratic participation and setting the social justice agenda (Moorosi et al., 2020), digital governance (Williamson, 2016), global policy dynamics (Verger et al., 2016), sustainable development goals (Oliveira et al., 2022), or vocational education and training systems (Mende et al., 2023)—but often do not examine governance as an analytical construct, nor engage critically with the diversity of theoretical frameworks in use.

Furthermore, prior reviews have not consistently addressed the interplay between governance levels (transnational, national, regional, institutional, and individual), nor have they unpacked how empirical studies approach governance in their analytic design.

These gaps point to a need for a more integrated, interpretative, and conceptually focused synthesis.

This review positions itself in response to these limitations, advancing a structured understanding of how governance is conceptualized in studies focused on compulsory public education. Rather than imposing a unifying model, we adopt an interpretative lens that captures the diversity of theoretical and methodological approaches, while identifying patterns, tensions, and omissions that shape the contemporary debate. This rationale reinforces the aim and research questions presented in the next section.

1.3. Aim of the Study

Although the concept of governance has been increasingly mobilized in educational research, it remains underexplored, particularly in what concerns compulsory public education, which represents the most universally experienced level of formal education, often intertwined with municipal and local structures and at the center of national and local reforms. Investigating this level of education is particularly important since it relates to contexts of increasing decentralization, where state and non-state actors, at different levels, interact and are responsible for the interpretation and implementation of national educational policies while responding to local needs and constraints that directly shape educational equity and quality.

This review builds on the assumption that governance is not a fixed model but a contested and evolving concept, shaped by political, institutional, and epistemic dynamics. By analyzing how different studies conceptualize governance, we aim to contribute to a more nuanced understanding that connects macro-level transformations with meso- and micro-level enactments.

Thus, in the absence of integrative analyses, we argue for the need to carry out this systematic literature review (SLR) on compulsory education governance, focusing on two primary research objectives: firstly, mapping main problems and theoretical approaches used on governance conceptualization within the field of compulsory public education, and secondly, identifying empirical and theoretical insights to inform future research.

To this end, two questions structure our research, allowing a more wide-open perspective on data without imposing any theory or departure conceptualization.

- -

- How is governance conceptualized in the context of the compulsory public education system?

- -

- What contributions to future research emerge from this review?

Aligned with these questions, the review develops along four interpretative lines: (1) it identifies conceptual fragmentation in the field; (2) it proposes an articulation between levels of analysis, categories, and theoretical frameworks; (3) it reveals silences, asymmetries, and underexplored dimensions in governance studies; and (4) it suggests directions for future inquiry that can deepen or diversify the field of governance research (see Appendix B).

2. Materials and Methods

This study is conducted as an SLR, a research approach intended to assess the current state of knowledge on a specific topic by examining a substantial body of scientific literature and synthesizing the gathered material through a rigorous and reproducible methodology. The review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) methodology, a series of evidence-based guidelines to rigorously conduct systematic reviews and meta-analyses to ensure clarity of the process, its reproducibility, and its updatability (Butler et al., 2016; Page et al., 2021a, 2021b; Rethlefsen et al., 2021; Zawacki-Richter et al., 2020). In the review process, the steps proposed by Donato and Donato (2019) were adopted, according to the following sequence: (1) formulation of the research question; (2) construction of the research protocol; (3) definition of inclusion and exclusion criteria; (4) definition of the research strategy; (5) selection of studies; (6) internal quality assessment; (7) data extraction; (8) synthesis of results; (9) dissemination of results.

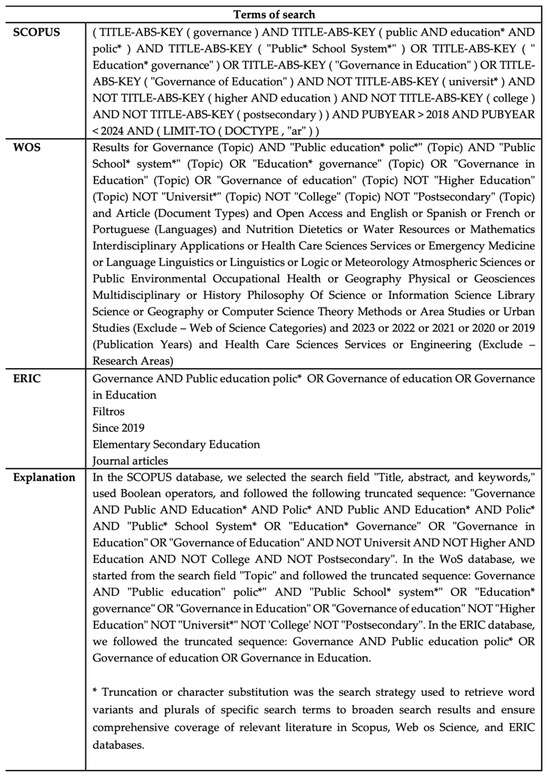

2.1. Research Strategy and Parameterization

In September 2024, three electronic databases were chosen as information sources regarding their international coverage and quality standards, ensuring that the included literature met academic rigor and relevance. More specifically, Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) was selected as it is the leading database in the field of educational research, while the Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus databases were selected for the identification of literature related to governance and public education, regarding their interdisciplinary nature and broader coverage (Chadegani et al., 2013; Pranckutė, 2021). Following deliberations among the researchers, the research protocol was established (see Appendix C), and relevant and appropriate keywords for the research strategy were identified, with consideration given to the initial questions. This exercise enabled the research to be given a broader scope (international coverage, relevance to the field of education and public policy) in the identification and selection of scientific articles relevant to the study, without restricting them to a single journal, theme, or research strategy.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria were developed to analyze the eligibility of studies obtained in the field of social sciences. The search was limited to articles published in a five-year timeframe, between 2019 and 2023 (see Appendix D). Only empirical, open-access peer-reviewed journal articles were included in this review. All selected studies were published in journals indexed in at least one of the academic databases previously mentioned. No restrictions were imposed regarding the country of publication, provided that the article was written in Spanish, French, English, or Portuguese. Gray literature, book chapters, dissertations, reports, and non-peer-reviewed publications were excluded to maintain methodological consistency and transparency. The final corpus included studies developed in the context of the compulsory non-higher public education system, and containing the term “Governance” in the title, abstract, and/or keywords. Considering the multilingual nature of the research and the utilization of various keywords, a cross-referencing process was undertaken to verify the variations in spelling. This was achieved through the translation of the pertinent terms into English, namely governance, education, public education policy, and public school system.

The following parameters were used to exclude articles: the absence of an abstract and/or keywords, restricted access to the full text, weak explanation of the methodological procedures used, the methodological nature of the studies (SLR, theoretical studies, legislative analysis, tool development), the focus of the analysis (higher education, adult education, preschool education, informal education), failure to answer the research question, other organizational focuses or contexts of analysis, and/or scientific areas not related to non-higher public education.

This review does not adopt a pre-defined theoretical framework to guide the analysis. Instead, it follows an explorative and inductive approach, allowing themes and categories to emerge directly from the selected studies. This decision aligns with the review’s aim to map conceptualizations of governance in compulsory public education, without imposing external theoretical lenses. By doing so, the SLR privileges empirical grounding and accommodates the conceptual diversity found in the field.

2.3. Extraction, Screening, and Selection Process

The preliminary research was conducted independently by one researcher. In accordance with the established parameters, the research yielded an initial corpus consisting of 275 scientific articles, which was subsequently reduced to 252 following the removal of duplicates.

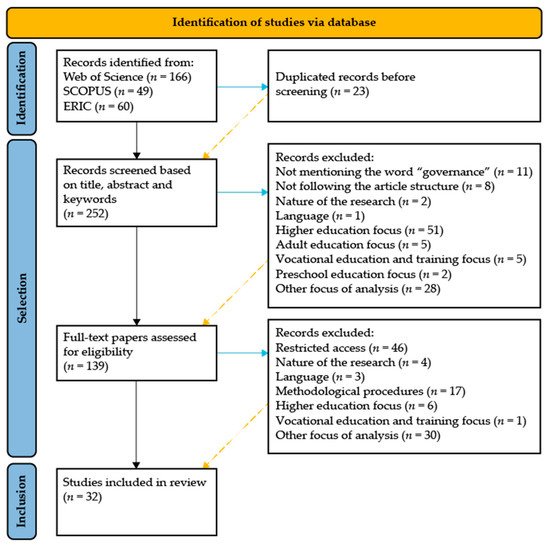

In subsequent phases, we examined the title, abstract, and keywords and excluded 113 articles from the study. The process of including and excluding articles through their full reading was carried out independently by two researchers. A third researcher was available to oversee any discrepancies, when required. Following this, we engaged in a collaborative process to validate the results, discussing differences until we reached a consensus. During this process, 107 articles were excluded, and the analytical corpus (see Appendix A) was established (n = 32). The PRISMA guidelines were fully respected (Figure 1), ensuring the reliability of the results, the applicability of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and the justification for the selection of studies to be included in the analysis corpus (Donato & Donato, 2019; Page et al., 2021a, 2021b).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the systematic review process (adapted from Page et al., 2021a, 2021b, based on results returned by the databases). In the figure vertical arrows represent sequential filtering phases; horizontal arrows represent exclusion points; dotted arrows represent records excluded from the next phase.

2.4. Data Extraction and Analysis

A total of thirty-two articles were obtained for the present systematic review. All articles were exported to the Mendeley reference management system and made available to the research team.

Then, a thematic analysis was conducted to identify patterns and categories relevant to the research questions. The thematic classification was supported by inductive analysis, which drew upon semantic and contextual data. The coding process was conducted manually by three researchers, and the data extraction process was recorded in a single Microsoft Excel document containing the following variables: (1) main study characteristics (article ID, publication year, author(s), publication title, keywords, publication journal, country/region of focus, database, and references); (2) methodological design (article ID, research purpose/main goals, questions/hypotheses addressed, sample, methods, data sources, main findings, main contributions, future research, and studies’ limitations); and (3) theoretical framework (article ID, theory/theoretical approach/point of departure, and concepts). The inductive thematic analysis was guided by Braun and Clarke’s six-phase framework (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Initial readings allowed the identification of open codes such as decentralization, school autonomy, data-based decision-making, actor agency, intermediary governance, and equity. These codes were grouped and refined into higher-level analytical categories such as educational governance transformation, policy enactment and capacity, and privatization and marketization, which are presented in the analytical matrix.

For example, data segments referring to teacher autonomy, curricular adaptation, and pedagogical freedom were grouped under the sub-theme actor agency, part of the broader theme policy capacity and enactment. Likewise, references to digital platforms, data infrastructures, performance data learning analytics, and adaptive algorithms were clustered under technology, digital governance, and data performativity.

To ensure the trustworthiness of the study, all coding decisions were discussed, with final decisions being made by consensus. An audit trail was maintained, and the thematic structure was revised throughout the process to ensure coherence and consistency. This collaborative process ensured agreement and minimized bias.

3. Results

The presentation of results is structured around the two guiding research questions and reflects the analytical reduction process applied during the data synthesis. The objective of this study was twofold: firstly, to map how governance is conceptualized in the field of compulsory public education systems, and secondly, to identify contributions for future research.

3.1. Studies’ Publication Characteristics

3.1.1. Number of Research Papers Published

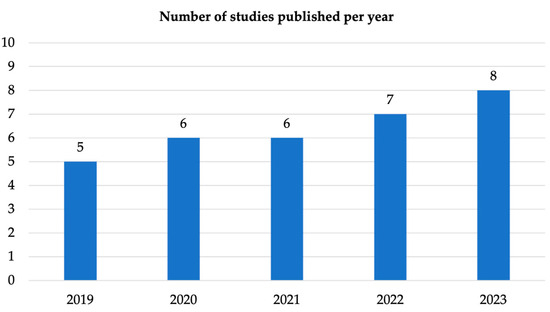

Figure 2 provides a detailed overview of the number of research papers published between 2019 and 2023. The thirty-two papers analyzed herein present empirical studies developed in the field of education. A comprehensive analysis of the extant data indicates that the number of publications has remained relatively stable over this period.

Figure 2.

Number of studies published by year between 2019 and 2023 (n = 32).

Publication output was lowest in 2019 (n = 5) and reached its highest point in 2023 (n = 8). In the remaining years, the number of publications varied from 6 in 2020 and 2021 to 7 in 2022.

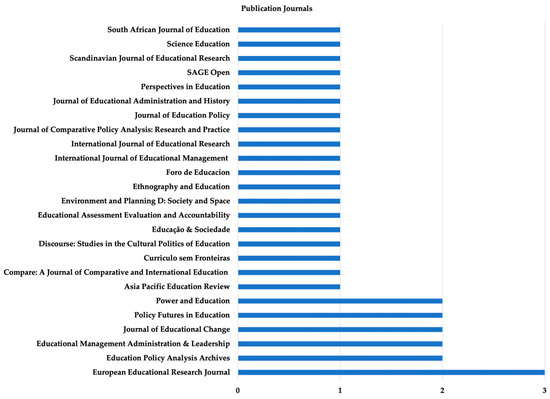

3.1.2. Publication Journals

All papers were peer-reviewed and published in 25 different open-access journals, as observed in Figure 3, which is presented below.

Figure 3.

Publication journals (n = 25).

The analysis of the data indicates that nineteen journals (76%) published only one article, while six journals (24%) did not fit this publication parameter, having published between two and three papers. The following journals have published two papers on the subject: Education Policy Analysis Archives (Antunes & Viseu, 2019; Sanginés & Ramírez, 2023), Educational Management Administration & Leadership (Koranyi & Kolleck, 2022; Simkins et al., 2019), Journal of Educational Change (Hashim et al., 2023; Lin & Miettinen, 2019), Policy Futures in Education (Kim, 2020; Kim & Choi, 2023), and Power and Education (Gamedze & Ruiters, 2023; Potterton, 2019).

As demonstrated in Figure 3, the journal with the highest number of publications is the European Educational Research Journal, with a total of three publications (Lunde & Ottesen, 2021; Milner et al., 2021; Salokangas et al., 2020).

The journals being examined cover a wide range of topics, which may indicate that researchers from various fields are interested in governance in public education and support the idea that educational governance is a fragmented field. Nevertheless, the publication of two or three articles in specific journals may also demonstrate the significance of governance in the field of education. Some other articles were published in journals that have a strong regional focus, such as the Asia Pacific Education Review (Tao, 2022), the Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research (Stenersen & Prøitz, 2022), and the South African Journal of Education (Sayed et al., 2020). Others address interdisciplinary topics that interconnect with areas such as sociology, exemplified in Educação e Sociedade (Cássio et al., 2020); management, represented by the International Journal of Educational Management (Nordholm & Adolfsson, 2023); innovation, addressed in Policy Futures in Education (Kim, 2020; Kim & Choi, 2023); or public policy, discussed in the Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice (Yan et al., 2023).

3.1.3. Geographical Distribution of the Studies

The geographical mapping reveals disparities in the representation of educational governance research, since publications are concentrated in the western education systems, with a particular focus on studies carried out in European countries (n = 14), especially in England, Sweden, Norway, and Portugal, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Geographical foci of studies.

Brazil, South Korea, England, and Sweden stand out with the highest number of studies (n = 3). They are followed by South Africa, Benin, the United States of America (USA), Norway, and Portugal with two studies each. Germany, Australia, Chile, China, Mexico, Taiwan, and Russia have only one study each. Three studies cover more than one country, namely Ireland and Norway; Denmark, England, and Italy; and Ireland and Finland. In the present context of analysis, thirty articles were written in English (94%). The only exceptions are two studies (6%) in Brazil, which were written in Portuguese.

This geographical distribution of the studies highlights the regions with the highest and lowest representation, as it is useful for understanding the contexts in which governance has been mobilized. As previously mentioned, most studies were conducted in countries from North America and Europe, with a particular focus on England (Greany, 2022; Peruzzo et al., 2022; Simkins et al., 2019) and Sweden (Andrée & Hansson, 2021; Lunneblad, 2020; Nordholm & Adolfsson, 2023), which may reveal some geographical trends. This evidence suggests that results may not be generalizable. Studies from South America and Sub-Saharan African countries are still incipient, despite the challenges posed, especially in terms of social inequalities and limited resources. Studies analyzing multiple countries indicate an effort to understand governance in comparative terms.

However, although the representation between countries in the “Global North” and the “Global South”3 is balanced in numerical terms, the cases of Russia (Piattoeva, 2021) and China (Tao, 2022) remain pertinent, with challenges that arise from their distinctive governance models in divergent socio-political and economic contexts. This evidence suggests that results may not be generalizable. Future studies should prioritize research in underrepresented contexts, expand comparative analyses, and incorporate local perspectives to facilitate the understanding of educational governance in a broader way. The emphasis on underrepresented contexts and the inclusion of local perspectives may reveal some overlooked issues in governance narratives. The inclusion of multiple perspectives will enrich the field and provide more relevant insights to understand educational governance in diverse education systems.

3.2. Methodological Frameworks

An examination of the methodological frameworks employed across the studies uncovers patterns in design, scope, and data collection strategies. All studies (n = 32) present objectives, which are associated with the formulation of hypotheses (n = 1) or questions (n = 13). The papers are mostly qualitative (n = 30), representing 93.8% of the analyzed corpus. We register one that used a mixed-method approach (Koranyi & Kolleck, 2022) and one with a quantitative methodology (Cuéllar et al., 2021). In terms of methodological design, 12 studies (37.5%) are classified as case studies (n = 4), comparative studies (n = 2), ethnographic studies (n = 2), empirical studies (n = 2), and exploratory studies (n = 2). Twenty studies (62.5%) do not mention any type of classification or categorization.

Data collection was mainly carried out through document collection (n = 27), combined with individual interviews (n = 18) and group interviews (n = 1), as well as focus groups (n = 2), observations (n = 3), and questionnaire surveys (n = 3). The collection and analysis of documents was based on a wide variety of sources, organized into the following categories: legislation, strategic documents, directives, reports, action plans, partnership agreements, memoranda, academic papers, press releases, news articles, website content, surveys, and field notes.

In this context, the application of more than one data analysis and processing technique is mentioned in eighteen articles, corresponding to 56.25% of the analyzed corpus. Document thematic analysis (n = 23) and content analysis (n = 20) emerged as the predominant analytical techniques, while a smaller number of studies employed critical discourse analysis (n = 3), statistical methods, both inferential and descriptive (n = 3), and network analysis (n = 3). The use of only one data analysis and processing technique is mentioned in fourteen studies, representing 43.75% of the analyzed corpus. Twenty-one studies mention the involvement of participants, representing 65.6% of the analyzed set. The participants identified in the studies are diverse and were organized into categories, as shown in Table 2, according to their degree of influence and the roles they play. Nine studies identify only one category of participants, six identify five categories, one identifies four categories, and six identify three categories.

Table 2.

Participants per study.

The presence of teachers and/or educators, as well as school principals and leaders, is noted in eleven studies. Seven studies refer to the collaboration of different specialists in the field of education. Six studies refer to the participation of policymakers, while five mention the participation of government officials, ministries, state secretariats, or national agencies. The participation of parents, as well as that of leaders, members, and/or representatives of foundations and public–private partnerships (PPPs), is evident in four studies. Three studies mention the inclusion of members of local and regional authorities, as well as members or representatives of trade unions. The categories of students, charter school administrators, and school workers/technicians are present exclusively in two studies.

In line with the nature and methodological design of the studies that used only documentary sources, eleven studies (34.4%) did not involve participants (Antunes & Viseu, 2019; Cássio et al., 2020; Joo & Halx, 2022; Kim, 2020; Kim & Choi, 2023; Lunde & Ottesen, 2021; Ødegaard & Gunnulfsen, 2023; Peruzzo et al., 2022; Sayed et al., 2020; Stenersen & Prøitz, 2022; Tao, 2022).

As for the presentation of study methodological limitations, twenty-one (65.6%) explicitly make this reference. In seven studies (33.3%), the limitations are related to the generalization of results due to the size and diversity of the sample (Koranyi & Kolleck, 2022; Sanginés & Ramírez, 2023), the context (Milner et al., 2021; Piattoeva, 2021; Tao, 2022), and the nature or type of studies (Lunneblad, 2020; Simkins et al., 2019). The remaining fourteen studies (66.7%) have limitations associated with (1) the strategy adopted in data collection, particularly in relation to the source, the instrument used, and the timeline versus the scope of the data (Cuéllar et al., 2021; Greany, 2022; Kim & Choi, 2023; Ødegaard & Gunnulfsen, 2023; Peruzzo et al., 2022; Stenersen & Prøitz, 2022; Yan et al., 2023); (2) inclusion and exclusion criteria for participants, particularly regarding sample size and diversity (Lin & Miettinen, 2019; Lunde & Ottesen, 2021; Nordholm & Adolfsson, 2023; Salokangas et al., 2020); (3) research context, specifically in relation to geographical, political, socioeconomic, historical–cultural, or other aspects (Andrée & Hansson, 2021; Hashim et al., 2023; Kim, 2020).

Of the thirty-two articles examined, thirty-one (96.9%) refer to the importance of future research (Andrée & Hansson, 2021; Bulgrin & Sayed, 2023; Bulgrin & Semedeton, 2022; Cássio et al., 2020; Cuéllar et al., 2021; Gamedze & Ruiters, 2023; Greany, 2022; Gulson & Sellar, 2019; Hashim et al., 2023; Joo & Halx, 2022; Kim, 2020; Kim & Choi, 2023; Koranyi & Kolleck, 2022; Lin & Miettinen, 2019; Lunde & Ottesen, 2021; Lunneblad, 2020; Milner et al., 2021; Nordholm & Adolfsson, 2023; Ødegaard & Gunnulfsen, 2023; Peruzzo et al., 2022; Piattoeva, 2021; Potterton, 2019; Salokangas et al., 2020; Sanginés & Ramírez, 2023; Sayed et al., 2020; Simkins et al., 2019; Stenersen & Prøitz, 2022; Tao, 2022; Tarlau & Moeller, 2020; Viseu & Carvalho, 2021; Yan et al., 2023), while twenty-one (65.6%) simultaneously mention limitations associated with the results and the need for further research. Such limitations highlight the need to adopt more inclusive and effective research methodologies and strategies capable of covering different realities.

3.3. Theoretical, Conceptual, and Empirical Landscapes of the Studies

This analysis reveals the existence of theoretical, conceptual, and empirical approaches that allow for the application of different lenses, broadening the understanding of educational governance conceptualization. The identified research problems and themes are not merely descriptive or incidental; rather, they represent interpretative angles through which governance is constructed and mobilized in the field. In this sense, they are constitutive of the very conceptualization of governance in compulsory public education, reflecting the plurality and contestation that mark the field.

3.3.1. Research Problems and Thematic Contributions

The review reveals several interrelated research problems and themes (Table 3) reflecting how governance is being conceptualized and studied in compulsory education. Theoretical frameworks, key concepts, and questions addressed in the studies supported the thematic coding process in an inductive-based approach to identify the main problems and themes of research. The contribution can be twofold, as the themes guide the mobilization of theory and allow theoretical and conceptual transversality and alignment when answering the research questions. Together, they support a structured interpretation of how educational governance is problematized and enacted across various contexts.

Table 3.

Research problems and themes.

- Educational governance transformation

One of the central themes in the current literature is the transformation of how compulsory education is governed. Studies indicate a shift from hierarchical and centralized models (with some exceptions from governance regimes like China or Russia) toward a more complex, hybrid, and networked scenario. This emerging framework involves multiple levels and actors. Studies reveal that this shift responds to neoliberal pressures, decentralization processes, digitalization, and the growing influence of non-state actors. The state remains present but interacts in different ways with a wide range of actors, giving rise to new forms of governance. Concepts such as meta-governance, heterarchy, or hybrid accountability underscore the fluid boundaries between state, market, and civil society, creating space for emergent hybrid organizational arrangements. It further illustrates how educational governance is being reconceptualized as a dynamic and contested domain.

- Policy capacity and policy enactment

Another recurring concern is that educational policies are not implemented in a linear or uniform way. Instead, they are mediated by key ideas and actors who interpret, adapt, and reshape them in their specific contexts. How a policy is experienced depends on how people understand it within their specific institutional culture. Policy enactment is thus discursive and practical, shaped by contexts, beliefs, and capacity. Challenges include policy formulation and implementation, as well as policy capacity—analytical, operational, and political—for education policies to succeed. Understanding educational governance therefore implies the ability to translate policy into practice, where ideas become routines and intentions take shape in schools.

- Non-state and intermediary actors

The increasing influence and involvement of non-state actors, including international ones, in educational policymaking is another central theme. These actors influence governance through international networks, technical tools, and public–private partnerships. International organizations such as the OECD, the World Bank, and UNESCO serve as knowledge brokers and policy advisors, advancing international agendas for accountability, comparison, and empowerment. In this context, philanthropic foundations, technology companies, media, think tanks, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) are also identified as strategic actors, as they articulate resources, expertise, and symbolic influence by collaborating to develop policies through advocacy, funding, data production, and technical legitimacy. Operating beyond traditional democratic bodies, they challenge the distinction between public and private boundaries, local and global dynamics, and limit educational authority. In this perspective, governance is conceptualized as a multifaceted and relational field where power, knowledge, and influence are in hybrid and contentious configurations.

- Privatization and marketization of education

Relatedly, the intensification of education privatization and marketization processes, marked by the introduction of market logic, new private actors, and rearrangements in the functions of the state, is also highlighted. Studies indicate that educational governance is being reshaped by policies that transfer part of the provision of educational public services to non-state actors—through public–private partnerships, voucher programs, charter schools, and technological platforms. Neoliberal rationality in the discussion links efficiency, innovation, and performance to business logic. The activities of philanthropic foundations or EdTech companies show a type of indirect or “soft” privatization, where influence is exerted through knowledge production, strategic financing, and the imposition of corporate management models. Consequently, governance no longer remains exclusively public. It operates in hybrid environments, where the role of the state is redefined as coordinator, facilitator, or regulator of educational markets. The impacts of these changes must be understood.

- Technology, digital governance, and data performativity

Technology, digital governance, and data performativity are other concerns, regarding the way they mediate and shape educational governance. In this context, digitalization, datafication, and the use of data infrastructures are discussed as new policy instruments, capable of reconfiguring relationships between governments and citizens, transforming the way education is governed. Digital platforms, algorithms, learning management systems, dashboards, and databases became central in the production, circulation, and sharing of information, as they collect and organize data and introduce performative effects, making visible and quantifiable what should be governed—such as school performance, teacher effectiveness, or resource use. These devices function as tools for monitoring, regulating, and comparing various schools leading to government actions that depend on the technical interpretation of reality. At the same time, metric-based quantification and evaluation consolidate themselves as powerful tools for determining what should be valued in education. Public policy treats standardized tests, rankings, and performance indicators as objective truths, despite their inherent political and epistemological choices. Thus, digital technology is not neutral: it structures power relations and defines who has the authority to decide what counts as “good” education. This decision-making is influenced by specific data and underlying logic.

- Crises and critical events

The COVID-19 pandemic is a significant moment of disruption, as it has profoundly changed the governance of education. In the review, studies discuss state decisions about the suspension of large-scale exams and the implementation of digital platforms, exposing both the system’s weakness and adaptive capacity. In this vein, studies show that responsibilities were temporarily restructured, while state centrality was imposed, and that this accelerated the entry of major EdTech companies such as Google and Microsoft into the educational ecosystem. This emergency provided a means to legitimize new public–private partnerships, and digitization has become a strategy for educational continuity and reform. The pandemic exposed and exacerbated existing pedagogical inequalities and infrastructural deficits while also challenging traditional governance models and their capacity to respond effectively to crises. Thus, the crisis has accelerated digitization, privatization, and state reconfiguration.

- Equity and social justice

Finally, the review highlights concerns related to distributive effects of governance reforms. Studies explore how governance reforms and instruments influence educational inequalities by reproducing them or by attempting to correct them, intentionally or not. As pointed out by some authors in contexts such as South Africa (e.g., Gamedze & Ruiters, 2023; Sayed et al., 2020), or Norway (e.g., Ødegaard & Gunnulfsen, 2023), financing and accountability policies have revealed several limitations in achieving equity and inclusion. Other studies emphasize the risks of privatization and school choice as mechanisms that exacerbate segregation. As expressed previously, the pandemic has exacerbated existing inequalities by transferring pedagogical responsibilities to digital environments with unequal access. Therefore, equity and quality emerge as critical criteria for assessing the distributive effects of contemporary forms of educational governance.

To enhance clarity, Table 4 summarizes the main themes and sub-themes emerging from the inductive coding process.

Table 4.

Themes and sub-themes of educational governance in compulsory education.

In summary, these themes and sub-themes reflect the conceptual diversity and empirical richness of current research. These categories serve as an entry point into the analysis of how governance is understood, enacted, and contested across education systems.

3.3.2. Levels of Analysis

Studies examine educational governance across several interconnected levels, ranging from transnational influences to the agency of individual actors. In this review, and building upon the coding structure, we organize the findings according to four commonly used levels in governance research: micro, meso, macro, and transnational. These levels are not mutually exclusive as they often intersect within the same study. However, identifying their prominence helps clarify how governance is conceptualized across contexts.

- Micro level: individual actors and professional agency

At the micro level, ten studies examine the roles of students, parents, and community members, highlighting the way they are shaped by and actively contribute to the implementation of educational policies and practices (e.g., Antunes & Viseu, 2019; Bulgrin & Semedeton, 2022; Greany, 2022; Hashim et al., 2023; Kim & Choi, 2023; Lunneblad, 2020; Peruzzo et al., 2022; Piattoeva, 2021; Potterton, 2019; Sayed et al., 2020).

Additionally, ten studies address teachers’ autonomy, instructional practices, and professional identity, emphasizing their pivotal role in enacting and adapting governance mechanisms (e.g., Andrée & Hansson, 2021; Bulgrin & Semedeton, 2022; Cuéllar et al., 2021; Hashim et al., 2023; Lunde & Ottesen, 2021; Ødegaard & Gunnulfsen, 2023; Peruzzo et al., 2022; Piattoeva, 2021; Salokangas et al., 2020; Sanginés & Ramírez, 2023).

- Meso level: schools and intermediary structures

At the meso level, fourteen studies address school level governance, examining how policies are enacted, and education is delivered (Antunes & Viseu, 2019; Cuéllar et al., 2021; Gamedze & Ruiters, 2023; Greany, 2022; Hashim et al., 2023; Lin & Miettinen, 2019; Lin & Miettinen, 2019; Lunneblad, 2020; Milner et al., 2021; Ødegaard & Gunnulfsen, 2023; Sayed et al., 2020; Simkins et al., 2019; Tao, 2022; Yan et al., 2023).

Thirteen additional studies explore intermediary governance structures, including regional departments, school networks, and hybrid organizations. These actors operate between national authorities and schools, and combine hierarchical, market, networked, and community-based logics (Bulgrin & Sayed, 2023; Cássio et al., 2020; Gamedze & Ruiters, 2023; Greany, 2022; Hashim et al., 2023; Kim & Choi, 2023; Koranyi & Kolleck, 2022; Lunneblad, 2020; Piattoeva, 2021; Sayed et al., 2020; Simkins et al., 2019; Viseu & Carvalho, 2021; Yan et al., 2023).

- Macro level: national governance and reform agendas

At the macro level, twenty-one studies adopt a systemic perspective. They focus on national reforms, such as decentralization, privatization, marketization, or digitalization and analyze how national policy agendas are influenced by historical, political, and ideological factors and contexts (e.g., Antunes & Viseu, 2019; Bulgrin & Sayed, 2023; Bulgrin & Semedeton, 2022; Cássio et al., 2020; Gamedze & Ruiters, 2023; Greany, 2022; Gulson & Sellar, 2019; Kim, 2020; Koranyi & Kolleck, 2022; Lin & Miettinen, 2019; Lunde & Ottesen, 2021; Milner et al., 2021; Nordholm & Adolfsson, 2023; Ødegaard & Gunnulfsen, 2023; Salokangas et al., 2020; Sanginés & Ramírez, 2023; Sayed et al., 2020; Simkins et al., 2019; Stenersen & Prøitz, 2022; Tao, 2022; Viseu & Carvalho, 2021).

- Transnational level: global influence and policy diffusion

The transnational level is addressed in nine studies that explore the role and influence of international organizations, such as the OECD, UNESCO, and the World Bank. These actors promote policy convergence and the diffusion of practices that shape “domestic” governance through global instruments, international rankings and evaluation systems (e.g., Bulgrin & Sayed, 2023; Gamedze & Ruiters, 2023; Greany, 2022; Hashim et al., 2023; Joo & Halx, 2022; Kim, 2020; Kim & Choi, 2023; Lunde & Ottesen, 2021; Tarlau & Moeller, 2020).

This multilevel framework highlights how educational governance is negotiated across actors, institutions, and geographies. It underscores the complexity of educational governance by illustrating how global actors influence national agendas, how institutions and intermediaries mediate policy enactment, and how individual actors interpret and contest practices in their everyday contexts.

3.3.3. Actors and Entities Governing Education

This review reveals diverse categories of actors and entities that participate in various spheres of educational governance. Some are directly involved as participants in the studies (as shown in Table 2), while others are identified for their role and influence in the context of the empirical studies analyzed. These policy actors and entities include national and subnational governments; international organizations; philanthropic foundations; EdTech companies and commercial actors; non-human actors (data, algorithms, and technologies); media; think tanks; networks; teachers, principals, and school administrators; parents, students, and communities.

National and subnational governments include ministries, agencies, and local authorities. They manage hierarchical governance structures by setting priorities, creating rules, and incentives (Bulgrin & Semedeton, 2022; Cássio et al., 2020; Greany, 2022; Tao, 2022). In decentralized systems like Denmark, national legislation is implemented at the local level, by municipalities and networks, as discussed by Milner et al. (2021), while in centralized systems, like China, local governments are peripheral actors (Tao, 2022).

International organizations like the OECD, UNESCO, the European Union, and the World Bank play a significant role in educational governance, acting as knowledge brokers and policy promoters. They influence domestic policy through agendas, standards, and large-scale assessments such as PISA (e.g., Bulgrin & Sayed, 2023; Joo & Halx, 2022; Kim, 2020; Kim & Choi, 2023; Milner et al., 2021; Stenersen & Prøitz, 2022). Their influence is central to understanding global governance dynamics.

Philanthropic foundations are increasingly recognized as key intermediary actors, as they shape educational agendas through expertise-driven advocacy, funding, and network participation. They often promote technocratic and meritocratic approaches aligned with neoliberal ideologies (Viseu & Carvalho, 2021; Tarlau & Moeller, 2020; Koranyi & Kolleck, 2022). Financially strong philanthropic actors may control educational networks, impacting both content and governance structures, which reflects on educational outcomes (Gamedze & Ruiters, 2023).

EdTech companies and commercial providers are revolutionizing educational governance via digital platforms and data systems, especially by providing data infrastructures and data-driven products and services to public systems. Their strategies include lobbying, marketing, and influential networked partnerships (Peruzzo et al., 2022; Sanginés & Ramírez, 2023).

The involvement of non-human actors is emphasized in three studies, regarding data systems, metrics, and digital technologies as governance instruments. They structure decision-making and accountability frameworks, influencing teaching and learning practices, through automated systems of data collection (e.g., Lunde & Ottesen, 2021; Piattoeva, 2021).

The media’s role is emphasized in three studies regarding its considerable influence on the public. The significance of these entities relies on their capacity to confer public visibility, as well as to cultivate social and political agendas (Antunes & Viseu, 2019). Accordingly, policy actors comprehend the media as a powerful policy tool for achieving their objectives (Kim, 2020; Tarlau & Moeller, 2020).

Think tanks are portrayed as acting in the social and cognitive dynamics of education policy. They bridge different social worlds such as the private business sector, academia, and political elites (e.g., Cássio et al., 2020; Koranyi & Kolleck, 2022; Viseu & Carvalho, 2021). The influence of these actors often materializes through their active involvement in communicative and coordinating policy-related spaces.

Understanding network influence through the long-term interactions and informal relationships among a plurality of actors (government, public agencies, private companies, communities, and social groups) is critically important. These relationships are predominantly characterized by trust, with the exchange of resources serving to engender and perpetuate mutual benefits for the actors involved (e.g., Tao, 2022). Their growing role in governance is linked to privatization and marketization processes, and they contribute to both coordination and contestation.

Although often positioned as policy recipients, teachers, principals, and school administrators interpret, mediate, and implement reforms within local contexts based on their professional experiences, beliefs and institutional contexts. In the studies, they are presented as operating at local levels, making judgments and decisions on educational resource assessment, curriculum alignment, and educational design. Their roles in school improvement and curriculum design make them central agents of governance enactment—especially in decentralized systems (e.g., Andrée & Hansson, 2021; Ødegaard & Gunnulfsen, 2023).

Other policy actors include parents, students, community members, and civil society. They are portrayed as influencing educational governance through pressure mechanisms, public policy debate and community-based action (e.g., Bulgrin & Semedeton, 2022; Lunneblad, 2020; Milner et al., 2021; Peruzzo et al., 2022; Potterton, 2019; Sanginés & Ramírez, 2023; Tao, 2022).

Overall, the analysis indicates that the landscape of educational governance is progressively influenced by the interactions among different actors, each possessing distinct levels of authority, roles, and objectives. This dynamic interaction at different levels fosters more collaborative approaches. Nonetheless, it also creates new tensions, conflicts, and obstacles for both centralized and decentralized educational governance systems. In essence, the studies extend much beyond the view of governance as solely a function of the state or central bureaucracy (“old governance”), reflecting the emergence of “new governance”, hybrid, multi-actor and contested in nature.

3.3.4. Theories and Concepts

Table 5 synthesizes the main theoretical frameworks and key concepts mobilized in the reviewed studies. This thematic categorization is grounded on the theoretical alignment and analytical contributions of the studies, and performed through an inductive approach, supported by semantic and contextual reading of data. Although some theoretical overlaps exist, five dominant approaches were identified, each closely aligned with the research problems and thematic areas outlined earlier (Table 3).

Table 5.

Theoretical and conceptual approaches.

These frameworks offer a deeper understanding of educational governance conceptualization and operationalization processes.

These frameworks provide a deeper understanding of how educational governance is conceptualized and operationalized. They highlight the mobilization of theories and concepts, as well as their analytical contribution to empirical inquiry and analytical interpretation. By applying different lenses, the studies frame educational governance as a dynamic and complex field in transformation, rather than one fixed hierarchical model. Additionally, mapping theories and concepts highlights the complexity of governance analysis.

3.3.5. Empirical Uses of Governance

Studies adopt different definitions and uses for the concept of governance, reflecting its conceptual flexibility and diverse epistemological positions.

Kim (2020), following Pierre (2000) and Rhodes (2000, 2007), defines governance as a process involving governing networks, which implies coordination interactions between central governments and other policy actors to reach agreeable decisions. Similarly, Kim and Choi (2023, p. 4), based on Milward and Provan’s (2000) work, discuss governance as “a form of social adjustment to solve problems of any group or organization”. This concept goes beyond traditional governments and state authority, emphasizing the need for organized rules and collective action. Additionally, Bulgrin and Sayed (2023), in alignment with UNESCO (2008), focus on governance as the process of operationalizing various national and subnational responsibilities and decision-making procedures. In a different way, Ødegaard and Gunnulfsen (2023), referencing Ball’s perspective, portray governance as a global shift in how public services, organizations, and initiatives related to performance control and competition are discussed (Ball, 2008).

Koranyi and Kolleck (2022, p. 948) highlight the empirical aspects of governance, reinforcing it around “structures and processes for collective decision making to direct, coordinate, and allocate resources” (Provan & Kenis, 2008; Vangen et al., 2015). They connect this concept to the patterns of interaction between horizontal and vertical actors (Sørensen & Torfing, 2014). Additionally, they also discuss meta-governance as the process of planning and coordinating networks by individuals or groups, either inside or outside an organization. Cássio et al. (2020) analyze network governance by tracking Ball’s work in fostering heterarchical structures and how people and organizations cross and expand boundaries as they move back and forth between public and private spheres, sharing goals and resources, both material and immaterial (Ball, 2016).

Across the reviewed studies, governance is used by almost all authors, often coined with prefixes that specify its application in specific contexts or highlighting certain values or objectives.

The analysis identified fifteen terms used in multiple studies: education/educational governance; network governance; school governance; digital governance; global governance; local governance; meta-governance; heterarchical governance; old/new governance; participatory governance; good governance; neoliberal governance; political governance; self-governance; state governance. Additionally, there are nineteen terms that appear uniquely in one study: centralized/decentralized governance (Simkins et al., 2019); community governance (Greany, 2022); devolved governance (Sayed et al., 2020); domestic governance (Joo & Halx, 2022); hybrid governance (Peruzzo et al., 2022); multi-scalar governance (Milner et al., 2021); normative governance (Nordholm & Adolfsson, 2023); political governance (Lunneblad, 2020); post-apartheid governance (Sayed et al., 2020); public governance (Tarlau & Moeller, 2020); regional governance (Peruzzo et al., 2022); regulatory governance (Nordholm & Adolfsson, 2023); reframed governance (Gulson & Sellar, 2019); rural governance (Tao, 2022); soft governance (Nordholm & Adolfsson, 2023); supranational governance (Lin & Miettinen, 2019); teacher governance (Peruzzo et al., 2022) traditional governance (Lin & Miettinen, 2019).

This variety of terms associated with governance in the field of compulsory public education underscores its polysemic character. Rather than indicating conceptual inconsistency, this diversity reflects differentiated analytical emphases, values, and institutional contexts. The various labels suggest that governance is in many ways shaped by political, epistemological, and contextual perspectives. Therefore, governance is far from being a neutral or fixed concept but rather a reflection of the competing priorities and frameworks mobilized by scholars in this domain.

In summary, the thirty variations of the term identified across the reviewed studies affirm the complex nature of governance. Rather than signaling conceptual inconsistency, this diversity reflects different analytical emphases and varied political, epistemological, and institutional viewpoints. In this vein, governance emerges not as a neutral or fixed term, but as a contested arena where different ideological positions and competing logics—centralization vs. decentralization, regulation vs. autonomy, and justice vs. efficiency—are continually presented and negotiated. This approach emphasizes the dynamic nature of educational governance, where various actors and institutional arrangements interact and influence one another, challenging authority and responsibility, which can both reinforce or challenge the democratic and redistributive commitments of public education.

3.3.6. Research Gaps

Studies address several research gaps that were clustered in an inductive-based analysis concerning the articles’ conclusions, contributions, and limitations. The coding process was conducted by thematic affinity and allowed us to identify five main research gaps that require further investigation.

- Policy enactment and the translation of policy into practice

The first cluster includes studies that point to the gap between political intentions and real practices in schools (policy enactment) as well as the role of communities, schools, school principals, and teachers as active mediators of policy (e.g., Lin & Miettinen, 2019; Nordholm & Adolfsson, 2023; Ødegaard & Gunnulfsen, 2023; Piattoeva, 2021; Potterton, 2019; Stenersen & Prøitz, 2022). Therefore, more attention is needed on the mediating role of local actors in shaping policy outcomes.

- Digitalization and data infrastructure

The second research gap concerns the social, ethical, and pedagogical effects of digital governance. Some studies point to unresolved questions such as privacy, children’s rights, and digital exclusion (e.g., Gulson & Sellar, 2019; Lunde & Ottesen, 2021; Sanginés & Ramírez, 2023) while others analyze the role of platforms and data infrastructures as governance tools (e.g., Peruzzo et al., 2022; Viseu & Carvalho, 2021). In this vein, more critical inquiry is needed into the governance functions and consequences of these technologies.

- Equity, social justice, and inequality

The third cluster refers to equity, social justice and inequity gaps. Several analyses reveal that educational policies often fail to adequately address the reproduction of inequalities (e.g., Cuéllar et al., 2021; Lunneblad, 2020; Sayed et al., 2020; Yan et al., 2023), the exclusion of marginalized actors (e.g., Sayed et al., 2020; Tarlau & Moeller, 2020), and the differentiated effects of policy in different contexts (e.g., Kim & Choi, 2023). This implies that governance research and policy design should critically integrate equity-focused frameworks.

- Influence of non-state actors

The fourth research gap refers to the role and influence of non-state actors. This gap raises the need to understand how philanthropic foundations, companies, and IOs influence and shape policy formulation and implementation (e.g., Koranyi & Kolleck, 2022; Viseu & Carvalho, 2021), and the impacts of this influence on political legitimacy and democratic accountability (e.g., Greany, 2022; Potterton, 2019; Tarlau & Moeller, 2020).

- Geographical asymmetries and Global South perspectives

The fifth research gap underlines the lack of research in Global South contexts and the need for approaches that are more sensitive to the cultural, historical, and institutional diversity of territories (e.g., Bulgrin & Semedeton, 2022; Gamedze & Ruiters, 2023; Sanginés & Ramírez, 2023; Sayed et al., 2020). Addressing this gap is crucial for a more globally inclusive understanding of educational governance.

4. Discussion

This SLR aimed to explore how educational governance has been conceptualized and studied in the context of compulsory public education from 2019 to 2023. Through an inductive, thematically driven analysis of thirty-two peer-reviewed studies, the review maps out major themes, theoretical approaches, and analytical categories that reflect how governance is interpreted, problematized, and operationalized across diverse contexts.

The findings indicate a persistent fragmentation in conceptual approaches and a lack of consensus regarding the definition of governance in education. Some studies utilize institutional theory, policy enactment theory, or sociocultural perspectives to characterize governance as the exercise of authority and distribution of responsibilities (e.g., Kim, 2020; Koranyi & Kolleck, 2022). In contrast, other research emphasizes hybrid and heterarchical models that incorporate decentralization, performativity, and multi-actor collaboration (e.g., Greany, 2022; Peruzzo et al., 2022; Gulson & Sellar, 2019). This coexistence of diverse—and sometimes contradictory—models of governance confirms the concept’s dual nature: it serves as both a normative ideal and an empirical construct, influenced by political, institutional, and epistemological dynamics.

By aligning emergent themes, theoretical frameworks, and levels of analysis, this review proposes an interpretative approach that aims to bring coherence to the field’s diversity (see Appendix E). The structured synthesis presented here offers a framework to understand governance not as a fixed or singular model, but as a dynamic field characterized by tensions—such as those between autonomy and control, centralization and decentralization, or public responsibility and marketization.

Another interpretative insight that emerges from the analysis is the symbolic and discursive construction of governance. According to Bulgrin and Sayed (2023), governance should also be understood as a contested arena of meaning-making, where terms such as “good governance,” “soft governance,” and “hybrid accountability” serve not only as descriptors but also as ideological markers. This discursive perspective reveals how governance instruments shape educational values and legitimize specific visions of equity, efficiency, or accountability (e.g., Piattoeva, 2021; Gulson & Sellar, 2019).

Furthermore, the review indicates that while the macro and meso levels of governance are well represented in the literature, there is a significant lack of studies that analyze how governance is enacted and negotiated at school and classroom levels. This insufficient attention to the micro level reflects a broader gap in linking policy design with its implementation, particularly concerning actor agency, local mediation, and pedagogical decision-making (Ødegaard & Gunnulfsen, 2023; Salokangas et al., 2020).

Additionally, the review highlights the growing influence of digital infrastructures and EdTech on governance structures. While some studies reference platforms, datafication, and algorithmic decision-making (e.g., Ødegaard & Gunnulfsen, 2023; Milner et al., 2021), there is a scarcity of research that analyzes the implications of digital governance on aspects such as surveillance, autonomy, and teacher professionalism. These tools are not neutral, as they encode specific governance logics that often intensify performativity and managerialism (Gulson & Sellar, 2019; Nordholm & Adolfsson, 2023).

Moreover, the involvement of non-state actors—including foundations, NGOs, consultancy firms, and EdTech companies—is increasingly significant in shaping policy agendas and accountability frameworks. Although these entities are sometimes framed as partners in innovation or capacity-building (Koranyi & Kolleck, 2022; Greany, 2022), they may also play a role in the marketization and privatization of public education. This raises important concerns regarding equity, legitimacy, and democratic governance (Cássio et al., 2020; Ball, 2016).

These interpretative lines converge to portray educational governance as a multilayered, contested, and evolving field that requires nuanced, critical, and actor-sensitive inquiry.

5. Limitations

This systematic review offers a comprehensive synthesis of how governance is conceptualized and enacted in the context of compulsory public education. However, several limitations must be acknowledged.

Methodological limitations include the exclusive focus on open-access, peer-reviewed articles published between 2019 and 2023. While this window captures post-pandemic transformations, it may exclude relevant earlier work. The review relied on manual, collaborative coding without the use of qualitative analysis software, which may have constrained coding depth despite traceability protocols. Additionally, although the review highlights significant qualitative richness, the analytical corpus includes only one quantitative and one mixed-method study, limiting the capacity to generalize findings or detect broader statistical patterns.

Sample limitations arise primarily from language filters, indexing asymmetries, and open-access constraints. Although the review included eligibility criteria for peer-reviewed articles published in English, Portuguese, Spanish, and French, the final sample was overwhelmingly composed of English-language publications (n = 30), with only two articles in Portuguese and none in French or Spanish. This is not merely a reflection of selection bias but also of broader systemic disparities in academic publishing, including the dominance of English-language journals in major databases and the uneven distribution of open access availability across regions. As a result, the review disproportionately represents Anglo-Saxon and Northern European contexts—particularly the UK and Nordic countries—while underrepresenting governance research from Latin America, Africa, and Asia. This regional skew may limit the diversity of educational governance models, actor roles, and policy dynamics analyzed, underscoring the need for future reviews to adopt broader search strategies and include more regionally and linguistically diverse sources.

Substantive limitations concern the thematic asymmetries in the literature. The review reveals a lack of integration between governance and leadership theories, even though leadership roles and practices are implicitly present in many studies. Future research could address this gap by explicitly connecting leadership frameworks (e.g., distributed leadership, instructional leadership) with governance arrangements and enactment processes at different levels (e.g., school, district, policy).

There is also a limited engagement with the governance of teaching and learning, despite frequent references to curriculum, assessment and accountability. Further empirical work could focus on how governance logics affect pedagogical practices and classroom-level decision-making, especially in relation to teacher agency and equity.

Moreover, few studies examined the transnational dimensions of governance beyond OECD and PISA-related dynamics. Similarly, the role of philanthropic actors, NGOs, and private foundations remains underexplored, despite their increasing presence in shaping education agendas, governance instruments, and evaluation practices across systems. Future reviews could explore alternative global actors, south–south cooperation, and emerging governance logics in underrepresented regions.

Finally, the review identifies a persistent asymmetry in actor representation, with some studies prioritizing policy narratives or institutional perspectives over the lived experiences and voices of school actors (teachers, students, families). More participatory and ethnographic research may help address this gap.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

This SLR aims to explore how governance has been conceptualized, problematized, and operationalized in recent empirical studies on compulsory public education. By analyzing 32 studies published from 2019 to 2023, the review identifies how governance is conceptualized as a dynamic, multi-scalar, and contested process, shaped by political, institutional, and epistemological tensions. Furthermore, it reveals a fragmented field characterized by theoretical diversity, unequal representation of actors, and several empirical gaps, including limited analysis at the micro level, underexplored digital influences, and insufficient attention to non-state actors’ influence, equity, and non-Western contexts.

Three key contributions emerge from the review. These contributions not only highlight the current state of research but also offer guidance for enhancing policy design, school leadership practices, and scholarly inquiry.

Mapping fragmentation and plurality: Governance is conceptualized through multiple and often competing lenses, such as network governance, performative governance, and meta-governance. This plurality, while enriching, calls for greater theoretical articulation.

Exposing conceptual and empirical gaps: The review uncovers asymmetries in actor representation, scale of analysis, and thematic focus. Micro-level enactments, classroom decision-making, and the symbolic dimensions of governance remain underexplored.

Bridging research and practice: The synthesis advances a structured mapping of research themes, analytical categories, theoretical approaches, and levels of analysis (Appendix E), serving as a heuristic tool to inform future studies.

Building on these findings, the review proposes actionable recommendations for different educational actors, including school leaders, policymakers, intermediary institutions, and researchers.

Recommendations for practice and research:

For school leaders: There is a growing demand for skills related to navigating complex policy environments, responding to accountability systems, managing data-driven practices, and engaging with non-state actors. These include the growing influence of digital governance technologies, data infrastructures, and EdTech platforms in shaping accountability, autonomy, and pedagogical decisions at the school level. Leadership development should therefore include critical governance literacy, enabling leaders to understand how governance logics—such as decentralization, performativity, or equity-oriented reforms—shape their autonomy, responsibilities, and strategic choices. Additionally, leaders must be prepared to critically engage with digital governance tools, such as data infrastructures and EdTech platforms, which increasingly influence pedagogical and organizational decisions.

For policymakers: Governance arrangements must be designed with attention to equity, contextual responsiveness, and actor agency. The review shows that top-down instruments, when disconnected from local realities, often produce unintended consequences. Policies should move beyond compliance-based models and foster participatory, context-sensitive processes that include frontline actors in their design and implementation. Furthermore, mechanisms should be in place to monitor the long-term impacts of governance reforms on educational quality, equity, and teacher professionalism.

For intermediary bodies (e.g., municipalities, education departments, evaluation agencies): These actors play a very important role in shaping the conditions of enactment between national policies and school-level practices. It is essential to invest in their institutional capacity to support schools, particularly in underserved or socioeconomically vulnerable areas. This includes technical, pedagogical, and organizational support, as well as ethical oversight of digital governance infrastructures and public–private partnerships. Intermediary bodies should also act as equity guarantors, ensuring that policy enactment aligns with democratic and redistributive commitments.

For researchers: Future research should address the gaps and asymmetries identified in this review by exploring how governance is enacted at the classroom level, where the effects of policies and accountability systems often become most tangible. There is also a need to critically examine digital governance and EdTech infrastructures, which increasingly shape decision-making, autonomy, and surveillance in education. Researchers are encouraged to connect leadership and governance theories, especially by analyzing how school leaders interpret and mediate governance instruments in practice. Finally, it is essential to include the voices of marginalized actors—such as teachers, students, and families—in governance research, using participatory and ethnographic approaches to better understand how governance is experienced, contested, or reshaped in everyday contexts. At the same time, future research should expand the methodological approach by integrating more quantitative and mixed-method studies, especially those capable of mapping governance effects across extensive systems or uncovering statistically supported correlations among governance structures, equity, and outcomes.

By aligning findings with four interpretative lines—(1) fragmentation of approaches, (2) need for articulation, (3) exposure of tensions and absences, and (4) future directions—the review contributes to positioning governance as a critical analytical lens for understanding the complexities of educational change. It also reinforces the importance of developing governance frameworks that are context-sensitive, inclusive, and analytically robust—offering a foundation for future empirical and policy-oriented work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.R. and M.S.; methodology, C.R.; validation, C.R., M.S., A.G. and A.N.-M.; formal analysis, C.R.; data curation, C.R.; writing—original draft preparation, C.R.; writing—review and editing, C.R. and A.G.; supervision, A.N.-M.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Funds through FCT- Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, I.P. (https://sciproj.ptcris.pt/157369UID (accessed on 4 February 2025)), under the project UIDB/00194/2020 regarding the Research Centre Didactics and Technology in the Education of Trainers (CIDTFF). https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/00194/2020.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EU | European Union |

| NGOs | Non-governmental organizations |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| SLR | Systematic literature review |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization |

Appendix A. Analytical Corpus

Table A1.

SLR analytical corpus.

Table A1.

SLR analytical corpus.

| Author(s) (Year) | Title | Keywords | Journal | Country/Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andrée and Hansson (2021) | Industry, science education, and teacher agency: A discourse analysis of teachers’ evaluations of industry-produced teaching resources | Discourse analysis, educational policy, governing, industry–school cooperation, science education, teacher agency, technology education | Science Education | Sweden |

| Antunes and Viseu (2019) | Education governance and privatization in Portugal: Media coverage on public and private education | Globalization; privatization; marginalization; media coverage; association contracts; Portugal | Education Policy Analysis Archives | Portugal |

| Bulgrin and Sayed (2023) | Discourses of international actors in the construction of the decentralisation policy: the case of Benin | Policy; education; decentralization; governance; discourse; critical discourse analysis; Foucault | Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education | Benin |

| Bulgrin and Semedeton (2022) | The importance of trust in education decentralisation in West Africa | Trust; education decentralization; governance; West Africa; post-colonialism; policy | Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education | Benin |

| Cássio et al. (2020) | Heterarquização do Estado e a Expansão das Fronteiras da Privatização da Educação em São Paulo | Políticas educacionais. Privatização da educação. Governança. Parceria público-privada. São Paulo (estado). | Educação & Sociedade | Brazil |

| Cuéllar et al. (2021) | Educational Continuity during the Pandemic: Challenges to Pedagogical Management in Segregated Chilean Schools | COVID-19; remote learning; educational continuity; pedagogical management; Chilean schools | Perspectives in Education | Chile |