Abstract

This study investigates how students of English Language and Literature Studies and those of Translation at the University of Maribor, Slovenia, perceive and engage with digital tools in academic and language learning contexts. Although students report high levels of confidence in their digital skills and express positive attitudes towards educational technologies, the survey results reveal a significant gap between perceived competence and actual usage. The study identifies the underutilization of institutional tools, limited awareness of resources available, and a reliance on general-purpose search engines rather than academic platforms. These findings highlight the need for improved digital literacy training, structured onboarding, and integration of digital tools into discipline-specific curricula. By focusing on a student population specializing in linguistics and translation in a Central and Eastern European context, this research contributes a localized perspective to broader discussions on digital transformation in higher education. The study offers applicable recommendations for enhancing institutional strategies and supporting students in becoming competent and critical users of educational technology.

1. Introduction

The digitalization of higher education has redefined the way students perceive knowledge and engage with both academic tasks and learning environments. Digital tools available to university students offer considerable potential to improve learning efficiency, language competence, and research output: from AI-supported writing assistants to academic databases and collaborative cloud platforms (Pikhart et al., 2024; Tutton & Cohen, 2025). Yet, as the digital learning landscape grows in complexity, it is clearer that mere availability of digital tools does not ensure their effective use (Selwyn, 2022; Ahmed & Roche, 2022). Many students struggle with digital literacy and the ability to integrate these tools into their academic work. The issue is often not addressed, particularly in regional and discipline-specific contexts (Yi & Wang, 2025; Mokhtar et al., 2024).

This gap is particularly present in language-intensive disciplines such as English and Translation Studies, where students are expected to master advanced writing, critical reading, and research tasks, which can all be supported by digital technologies (Karasaliu, 2024; Al-Ali, 2025). Tica and Krsmanović (2024) observe that today’s students are “born as ‘digital natives’,” to the extent that “the very notion of teaching and learning English without technology has become inconceivable” (p. 130). Yet, despite this, young people’s digital skills are generally heterogeneous and often unspectacular, and there is limited empirical evidence specifically on how language students at European universities engage with digital tools in their academic work. Current studies often treat digital competence as a general issue rather than a skillset shaped by academic discipline, pedagogical support, and local infrastructure (Ravikumar et al., 2024; Rodríguez et al., 2024).

In recent years, universities have responded to global digital education strategies by investing in digital transformation initiatives. The University of Maribor (UM) has adopted this broader trend through its 2021–2030 strategic plan (Univerza v Mariboru, 2021, p. 28), which emphasizes access to research and teaching technologies, scalable information and communication technology (ICT) infrastructure, and digital learning environments. These efforts mirror priorities found in the Rome Ministerial Communiqué (BFUG, 2020), the Magna Charta Universitatum (MAGNA, 2020), and the European Commission’s Digital Education Action Plan 2021–2027—ANDI (European Commission, 2023). UM’s digital support system includes a range of free-to-use digital tools—from licensed productivity software to academic databases and online learning platforms—with multilingual access designed to serve both Slovenian and international students.

While the institutional framework is ambitious, the degree to which students are aware of, utilize, and benefit from these tools remains underexplored, especially in Slovenia. This case study addresses that gap by examining how students of English and those of Translation at the Faculty of Arts in Maribor perceive and engage with the university-provided digital tools. Through a quantitative self-reported survey, it investigates students’ socio-demographic characteristics, usage habits, awareness levels, perceptions of tool effectiveness, and the non-technical challenges they face in digital learning environments. We surveyed students of English and Translation Studies—fields that have distinct curricula, yet share a common English language core, such as research tasks, engagement with English-language sources, and advanced writing tasks –, who both use similar digital tools in their studies, and compared them along the vertical (BA and MA) and horizontal line (English and Translation students).

By analyzing these dynamics, the study contributes to the research into digital literacy and educational technology in higher education. It offers insights for improving digital orientation, integrating tools into language-focused study programs, and strengthening institutional support for student engagement with modern digital technologies. What is more, by focusing on students in Slovenia, this study also acknowledges the influence of local linguistic and educational contexts on digital tool engagement. English holds a prominent position in Slovenian academia and society, mirroring broader globalization trends. As Šabec (2022) observes, English as a global lingua franca increasingly permeates even traditionally monolingual environments; in Slovenia, as in other Central European countries, national languages do not merely coexist with English in theory but interact with it in everyday academic, professional, and social practice (p. 16).

The article first reviews relevant international and Slovenian studies on digital transformation, digital literacy, and the use of digital tools in academic and language learning contexts in Section 2. Section 3 presents the methodology, participant profile, and survey design. Section 4 outlines the results, organized into five categories aligned with the research aims. Section 5 brings a discussion of key findings, relating these to broader theoretical and practical context, and in Section 6 we articulate the findings and their implications for the subject matter.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Digital Transformation in Higher Education Institutions

Digital transformation in higher education institutions (HEIs) has emerged as a comprehensive response to technological, pedagogical, and societal pressures shaping the academic landscape. While many HEIs are investing in digital infrastructure and innovation, the adoption of digital transformation strategies varies widely in scope and execution. Rivera-Gutiérrez et al. (2024) emphasize the need for solid strategic planning and adaptability in this domain, pointing to digitized content, personalized learning, and inter-institutional collaboration as key opportunities. Similarly, Benavides et al. (2020) describe digital transformation in higher education as an emerging but fragmented field, with most institutions adopting isolated rather than holistic approaches. Alenezi (2021) and Díaz-García et al. (2023) stress the necessity for aligning technological change with cultural adaptation, participative leadership, and data-informed decision-making. These studies underline that transformation goes beyond tools and platforms; it requires shifts in institutional values, governance, and mindset.

Digital transformation also demands attention to sustainability and equity. Shenkoya and Kim (2023) note that it enables educational innovation and sustainability through Education 4.0 practices, yet Kim et al. (2021) and Selwyn (2022) caution against uncritical adoption, highlighting digital divides and the need for ethical, inclusive integration of technology. As Gkrimpizi et al. (2024) argue, HEIs are unique entities, and their digital transformation processes must reflect their pedagogical missions and social roles. Notably, the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated these shifts (Akour & Alenezi, 2022), forcing institutions to reimagine education through flexible, digitally mediated models, and requiring teachers to upskill their creativity and strengthen their digital competence (Skrbinjek et al., 2024). Still, as Iftode (2020) points out, the tension between tradition and innovation persists, requiring deliberate management and long-term vision.

Recent studies indicate that successful digital transformation in higher education frequently depends less on technological availability and more on organizational and human factors, including stakeholder engagement, alignment with pedagogical objectives, institutional capacity, and cost (Singun, 2025; Feng et al., 2025; Gkrimpizi et al., 2023). Similarly, a global report by McKinsey & Company (2022) identifies a lack of awareness, limited deployment capabilities, and cost as the primary barriers to adopting digital learning tools, with lack of awareness being the most significant obstacle. Additionally, meaningful engagement with digital resources requires interactive, competence-focused learning environments (Malysheva et al., 2022), as well as balanced pedagogical approaches that complement rather than replace critical thinking and interpersonal interactions (Al-Ali, 2025; Tutton & Cohen, 2025). These insights directly informed our survey’s inclusion of items measuring student awareness, tool usage patterns, and perceived non-technical barriers such as training, digital overload, and institutional support.

2.2. Digital Literacy and Competence

As higher education relies increasingly on digital platforms for instruction, assessment, and communication, digital literacy has become a foundational academic competence. It is now widely acknowledged that digital literacy is not a single skill but a multidimensional set of capabilities ranging from technical proficiency to critical thinking and information evaluation, all of which are essential for navigating digital academic environments (Burgos & Anthony, 2024; Jiang, 2025; Ahmed & Roche, 2022; Yi & Wang, 2025). Digital literacy in academic contexts is not only about familiarity with a tool’s interface or basic functionality but also about meaningful and strategic use. In the context of this study, these terms refer to the deliberate selection of appropriate tools for specific academic or language learning goals, the ability to leverage advanced features to enhance efficiency and accuracy, and the critical evaluation of both the tool’s output and the information it processes.

Digital skills can also be regarded as “capitals”, defined as “socially valued, rare, and stratified sets of resources that are mobilized by individuals to improve their social status” and to “generate [other] social benefits” (Rodríguez-Camacho et al., 2024, p. 3). Some scholars (e.g., Calderón Gómez, 2021) see digital capital as a form of cultural capital (Bourdieu, 1986, 1996), which comprises competences, knowledge, and skills in various areas of culture. In Slovenia, several studies have shown the importance of cultural capital for educational (Kirbiš, 2020) and health literacy (Kirbiš, 2022), suggesting by analogy that digital competence may similarly impact student success.

Building on this conceptual foundation, recent studies have explored how students’ digital literacy levels directly affect their academic performance and experiences. Romi (2024) demonstrated that students’ academic effectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction are significantly influenced by their proficiency across common, educational, and advanced digital skills. Similarly, Rodríguez et al. (2024) report a positive correlation between digital competence and academic performance, although socioeconomic factors such as parental education and financial status also played a role. These studies highlight the benefits of strong digital skills but often offer broad generalizations across disciplines, without accounting for regional or cultural differences.

Furthermore, research emphasizes that digital literacy does not function in isolation but is influenced by learning strategies, access to institutional resources, and broader social and cognitive factors. For instance, Ravikumar et al. (2024) highlighted the mediating role of critical thinking and found that digital literacy positively offsets the negative impact of unstructured digital learning environments. Likewise, Zheng and Kim (2025) argued that metacognitive self-regulation and resource management strategies are key to transforming digital literacy into responsible academic behavior. Vodă et al. (2022) and Salazar Palomino et al. (2025) further emphasize the role of collaborative and communication-based digital skills, particularly among social sciences and humanities students. On the other hand, persistent gaps remain. Mokhtar et al. (2024) noted that students still face challenges in information-seeking and in evaluating digital sources effectively. Yi and Wang (2025) identified urban-rural gaps, especially in privacy and digital security awareness. These findings echo concerns from Ahmed and Roche (2022) about the uneven development and application of digital literacy frameworks across institutions. Taken together, the literature suggests that improving student digital literacy requires both individualized learning strategies and supportive institutional frameworks to ensure consistent, equitable, and context-aware skill development. This backdrop together with established frameworks (e.g., EU DigComp 2.1 or the upcoming DigComp 3.0) informed our survey design by motivating a dedicated section on digital competences, where students self-assessed their proficiency in key digital skill areas. This enabled a comparison between their self-perceptions and known strengths and gaps in digital competence.

2.3. Digital Tools in Language Education

Digital technologies in language learning, particularly in higher education, have recently acquired considerable importance. It has influenced all aspects of language learning, from the four skills to vocabulary, grammar, and communication. Researchers constantly report on the benefits of these tools, stressing their ability to increase learner’s engagement and motivation. They also provide tailored practice, and offer immediate feedback alongside rich multimedia input (Schilling et al., 2024; Pikhart et al., 2024; Paee, 2025; Deen & Mahmoud, 2025). Ram (2025) reports that “the adoption of digital technologies promotes motivation and engagement among learners in addition to facilitating language acquisition through the provision of immersive and interactive experiences” (p. 10).

These findings are supported by meta-analyses, showing that in higher education contexts, interactive digital tools have a positive influence on vocabulary retention, grammar proficiency, writing fluency, speaking confidence, and overall learner motivation (J. Li et al., 2025; Bobkina et al., 2025; Al Shihri et al., 2025). The combination of Computer-Assisted Language Learning (CALL) and AI-assisted pedagogical models further boosts motivation, participation, writing quality, and oral proficiency (Bahari et al., 2025). Also, immersive strategies, such as corpus-based instruction and computer-supported collaborative learning (CSCL), promote incidental vocabulary learning, reduce anxiety, and improve speaking skills (Reynolds et al., 2023; Dooly, 2007), while mobile-assisted language learning (MALL) promotes vocabulary growth and alleviates speaking anxiety by enabling practice in low-pressure settings (Cai & Zhang, 2023; R. Li et al., 2023).

AI-driven tools such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT (OpenAI, 2025), Google’s Gemini (Google, 2025), Anthropic’s Claude (Anthropic, 2025), and advanced machine translation systems (e.g., DeepL) are increasingly used by students to test understanding, simulate conversations, receive instant feedback on grammar and translation accuracy (Deep et al., 2025; Tutton & Cohen, 2025; Al-Ali, 2025), and gain insight into context-based language use (Karasaliu, 2024; Ahmad et al., 2024). In addition, the integration of digital tools into translation pedagogy has improved curriculum efficiency by automating assessment and reducing instructor workload (Khasawneh & Shawaqfeh, 2024). Studies indicate that such AI tools can foster learner autonomy, personalized learning, and fluency when used appropriately. For instance, interacting with conversational AI (chatbots or voice assistants) gives students on-demand speaking practice and individualized feedback, which can supplement human interaction. ChatGPT and similar models have even been used to explain grammar or suggest writing improvements, acting as always-available tutors.

Another key advantage of digital tools in language learning is their capacity to provide immediate feedback and promote active learner involvement. Karasaliu (2024) demonstrated this in an English for Specific Purposes course, where university students used Google Translate, ChatGPT, and My AI to translate economy-related texts. With instructor guidance, students compared outputs, identified translation errors, and proposed improvements, thereby strengthening their contextual understanding and translation awareness. The study highlighted enhanced comprehension, instant feedback, and personalized learning experiences as key benefits of integrating such tools into ESP instruction. In writing instruction, tools like machine translation and grammar checkers (e.g., DeepL, Grammarly) can serve as scaffolding by offering models and feedback that support language development. Research shows that DeepL helps English as a Foreign Language (EFL) learners improve syntactic complexity and accuracy by exposing them to more natural target-language input (Liang, 2024). Likewise, Vietnamese English majors using Grammarly reported gains in grammatical accuracy, sentence clarity, and writing confidence, while also noting limitations in handling complex or academic language and occasional suggestion errors (Nguyễn, 2025). Similarly, in listening and speaking, multimedia resources and speech recognition software enable learners to practice with authentic materials and get real-time evaluation. For example, automatic speech recognition technology (ASR) with corrective feedback leads to measurable improvements in pronunciation by displaying feedback on their spoken output (Ngo et al., 2023).

Additionally, digital collaboration frameworks such as Collaborative Online International Learning (COIL) and virtual exchange programs strengthen digital literacy, intercultural competence, and collaborative skills by providing wholesome learning experiences across institutions and cultures (Hackett et al., 2023; Hackett et al., 2024). Social media platforms, when employed strategically, further enhance digital competence and communication efficiency, complementing formal digital learning environments (J. Li et al., 2025).

Despite many benefits of digital tools in language education, the literature also points to key limitations. As Bobkina et al. (2025) emphasize, the effectiveness of these tools depends greatly on thoughtful integration into pedagogy. Without careful design, some digital resources may lead to superficial engagement or cognitive overload rather than meaningful learning. Over-reliance on AI and machine translation tools can obstruct critical thinking and creativity, as students may bypass the necessary cognitive effort involved in language learning (Gerlich, 2025; Zhai et al., 2024). There are also ethical concerns, since uncritical use of generative AI tools can undermine originality and learning integrity (Perkins, 2023).

In summary, research portrays a balanced view: digital tools offer great support for language learning—enhancing vocabulary, grammar and speaking practice, writing feedback, listening input—but their success depends on mindful implementation and overcoming challenges such as resource quality, inequitable access, and the need for digital pedagogy training. Scholars call for continued research and innovation to maximize benefits, such as AI-driven personalized tutors, or game-based learning, and avoid drawbacks, such as plagiarism, screen fatigue, or privacy issues. It is crucial to ensure that technology truly enriches language education rather than diminishes it.

2.4. Digital Situation in the Slovenian HEI Context

Turning to the Slovenian context, studies show that the trends observed globally are largely mirrored among Slovenian students and educators—with high awareness of digital tools’ potential but also gaps in digital literacy and inconsistent integration into formal language education. Slovenia has actively pursued digital transformation in education, aligning with European initiatives. Notably, the government adopted the European Union’s Digital Education Action Plan 2021–2027 (Akcijski načrt digitalnega izobraževanja—ANDI) in April 2022, which aims to establish a robust digital learning environment aligned with EU frameworks and prepare learners for life in a digital society (European Commission, 2023). The plan prioritizes the development of digital infrastructure, teacher training, and seamless ICT integration across education levels. The University of Maribor (UM) has aligned itself with this broader trend through its 2021–2030 strategic plan (Univerza v Mariboru, 2021), which emphasizes equitable access to research and teaching technologies, scalable ICT infrastructure, and digital learning environments.

Research on Slovenian students’ digital literacy and use of educational technology provides insight into how these policies translate into practice. While several other types of literacy among Slovenian young people and adults have previously been examined, for example, health literacy (Kirbiš et al., 2025; Lubej & Kirbiš, 2025) and climate literacy (Lubej et al., 2025), research on digital literacy among Slovenian young people remains limited and shows mixed results. Šorgo, Dolenc and Ploj Virtič (Šorgo et al., 2023; Dolenc et al., 2021) report that despite the forced transfer to online teaching during the COVID-19 period, the students’ digital literacy has, surprisingly, not improved considerably. Also, contrary to expectations, the usage of digital tools has not increased either, except for MS Teams. Building on these concerns, a recent study by Ferjan and Bernik (2024) examined digital competencies in Slovenia’s formal education system and revealed a significant imbalance: formal curricula dedicate relatively little time to explicit digital skills training, so students acquire most digital competencies informally or via a “hidden curriculum.” They found that by the time students reach higher education, their self-assessed digital competence is moderate: on the EU’s DigComp scale, most rated themselves at proficiency level 5 (out of 8), meaning they are comfortable using digital tools for routine tasks and personal needs, but have not progressed much further. A similar study by Pičulin et al. (2023) found that university students’ self-assessment results indicate the highest competence level as being in communicating, collaborating, and handling information using ICT; moderate competence in protecting devices and data, and the lowest competence level in digital content creation and technical problem-solving. In other words, Slovenian students tend to be proficient end-users of everyday technology (smartphones, social media, basic office software) yet may lack advanced skills or critical digital literacy. This plateau at intermediate skill levels underscores the need for more systematic development of digital competencies through formal instruction—a need that ANDI (European Commission, 2023) and the University of Maribor’s strategic plan (2021) seek to address.

Closely related is the question of students’ and teachers’ attitudes towards using digital tools for learning. Research by Štemberger and Čotar Konrad (2021) is instructive: they surveyed Slovenian teacher trainees (i.e., pre-service teachers) regarding educational technology use. Encouragingly, attitudes were predominantly positive—the vast majority believed digital tools can enhance teaching and learning, and they expressed willingness to use them in their future classrooms. However, a notable finding was that while Slovenian teacher trainees predominantly hold positive attitudes towards using digital technologies in education, they assess themselves as low-level users. This gap between attitude and self-assessed ability suggests that teacher education programs need to provide more hands-on experience with integrating ICT into lesson design.

Among university students, including language majors, engagement with digital technology is high, yet its use for language learning remains inconsistent and often lacks meaningful or strategic intent. Lazović and Jakupčević (2024) conducted a cross-border survey of tertiary-level students’ ICT use in English classes, focusing on Slovenia and Croatia. Students enrolled in the English study program at the Faculty of Arts, University of Ljubljana, reported frequent access to and positive attitudes toward ICT tools, which they found easy to use and helpful for developing English skills. They made regular use of institutional platforms like Moodle and various websites in the classroom. However, many students also indicated that they could study without ICT, and some expressed discomfort or nervousness when using digital tools for language learning. These findings suggest that while students are surrounded by technology and recognize its benefits, they may not consistently use it strategically for language development. The authors emphasize that effective ICT integration requires thoughtful planning and support, especially to help students become more autonomous and purposeful in their digital learning habits. One of the aims of our study is to examine whether this is also the case with the English and Translation students at the University of Maribor.

Another aspect of the Slovenian context is information literacy, which overlaps with digital competency in language learning. Boh Podgornik et al. (2016) had earlier drawn attention to Slovenian students’ information literacy levels, finding that many students struggled with higher-order skills such as critically evaluating online information and discerning reliable sources. They noted that being a confident user of gadgets does not automatically equate to being information-literate. This is highly relevant for language education today: students might, for example, use Google Translate or ChatGPT, but without guidance they may not question the output or quality of these sources. The 2016 study spurred efforts in universities to incorporate information literacy training (e.g., how to do research in English, how to use databases and digital libraries for language studies). In this context, our study analyzes whether and how students fact-check the information they receive online.

In summary, the convergence of findings from broad international research and specific Slovenian studies underlines the relevance of examining digital tool usage in language education—it is a timely issue with global significance and local urgency. Slovenia’s experience with digital tools in education exemplifies both the promise and the complexity of digital transformation. The adoption of Institutional initiatives like ANDI (European Commission, 2023) and universities’ own strategies have established strong foundations in infrastructure and policy, and students show enthusiasm for technology use. However, challenges remain in bridging the gap between general digital usage and purposeful academic application, enhancing formal digital literacy education, and supporting educators’ effective technology integration. Notably, research focusing specifically on digital engagement among language-focused students in Slovenia is scarce. This study aims to fill this gap by investigating English and Translation students at the University of Maribor, providing localized insights that complement Slovenian and broader European and global research on digital transformation in higher education.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design and Objectives

This study employed a quantitative, cross-sectional survey design to examine how students in English Language and Literature and Translation Studies at the Faculty of Arts, University of Maribor perceive and engage with university-provided digital tools in the context of academic and language learning. The study focused on both usage behaviors and perceived barriers to digital tool adoption.

For the purposes of this research, digital tools are defined as software, platforms, and online services offered or officially endorsed by the University of Maribor that have direct relevance to academic work and, in particular, to language learning. While the university provides access to a broad range of digital resources, we have included tools that are used or could be of use to language students, while excluding digital tools used primarily in other fields (e.g., specialized engineering software such as National Instruments’ LabVIEW (National Instruments, 2025a) and Multisim (National Instruments, 2025b), or MathWorks’ MATLAB (MathWorks, 2025a) and Simulink (MathWorks, 2025b)). These include productivity tools (e.g., Microsoft Word (Microsoft, 2025d), PowerPoint (Microsoft, 2025c), and Outlook (Microsoft, 2025b)), academic databases (e.g., UM:NIK (Univerzitetna knjižnica Maribor, 2025), ProQuest (ProQuest, 2025), Scopus (Elsevier, 2025)), virtual learning environments (e.g., Moodle (Moodle HQ, 2025), MS Teams (Microsoft, 2025a)), and specialized services such as the Slovenian-language proofreading tool Amebis Besana (Amebis, 2025) and cloud-based document sharing platforms. In addition to these university-provided resources, the survey also considered students’ perception and use of external tools, such as Grammarly (Grammarly Inc., 2025) and ChatGPT, where they were relevant to language learning.

To guide the investigation, the following research questions were posed:

- To what extent are students of English and Translation Studies at the University of Maribor aware of and engaged with digital tools provided by the university for academic purposes?

- How do students use digital tools to support specific language learning activities, including writing, grammar, vocabulary development, and translation tasks?

- What are students’ practices and levels of engagement with academic research tools, citation management software, and digital literacy behaviors such as fact-checking and upholding academic integrity?

- What non-technical barriers do students face in accessing and effectively using digital tools, and how do these challenges impact their learning experience?

Furthermore, the study also compares these findings across both academic levels (BA and MA) and both fields (English and Translation Studies).

3.2. Participants and Sampling

Participants were students enrolled in two BA study programs (years 1 to 3 and the additional year (Slov. absolvent)): English Language and Literature program, and Translation Studies—English program, and in three MA study programs (years 1, 2 and the additional year): English Teacher Training program, Non-Pedagogical English Studies program and English Translation and Interpreting program, all at the Faculty of Arts, University of Maribor. The responses of the BA and MA students were analyzed separately, while those within each study cycle were so homogenous that they were analyzed together. Given the substantial curricular overlap, particularly in linguistic and cultural content, the two programs were treated as a single population for the purpose of this study on language-focused digital tool engagement. Nevertheless, we also compared results between the fields, as even minor differences could reveal meaningful patterns in how students engage with these tools.

The survey was distributed to approximately 230 students (ca 160 in English Studies and ca 70 in Translation Studies), using a non-probability convenience sampling method. A total of 131 students responded, including exchange students and students on academic leave. By academic level, the respondents comprised 94 BA students and 34 MA students; by field, 91 were in English Studies and 37 in Translation Studies. The three Erasmus students were excluded from BA–MA and field-based comparisons, as they were not formally enrolled in the University of Maribor programs.

3.3. Survey Instrument

We developed a 43-item questionnaire to capture students’ digital practices and perceptions. The instrument included multiple-choice, Likert-scale, yes/no, and a few open-ended questions. The open-ended items invited students to describe challenges, perceived advantages, or suggestions related to digital tool use (e.g., barriers to adoption, reasons for non-use).

The survey consisted of a socio-demographic section and four thematic sections (see Table 1), each aligned with one of the study’s four research questions and grounded in relevant literature (see Section 2):

Table 1.

Survey Structure and Contents.

The instrument was developed with reference to digital education frameworks (e.g., DigCompEdu, DigComp 2.1) and refined through consultation with faculty experienced in digital literacy research. A pilot study conducted with a small group of students (5) aimed to assess clarity, comprehensibility, and completion time (~9–10 min), and to improve the survey’s face validity.

3.4. Procedure and Data Analysis

The survey was designed in Microsoft Forms. Students were invited to participate through class mailing lists and via student representatives. Responses were collected anonymously, and data were securely stored.

We analyzed quantitative data with descriptive statistics (means, frequencies, and percentages) and, where appropriate, we used inferential statistics such as chi-square tests to examine relationships between variables (e.g., year of study vs. tool usage).

Open-ended responses were analyzed separately using inductive thematic coding. Two researchers independently reviewed the responses, developed initial codes, and reached consensus on recurring categories (e.g., “paywall barriers,” “tool overload,” “lack of guidance”). Selected themes and illustrative examples of these qualitative insights are integrated into the Results (Section 4) to complement the quantitative findings.

While the survey was designed based on an extensive literature review and underwent expert validation, no formal psychometric validation (e.g., reliability testing, factor analysis) was conducted. This limits the ability to confirm the internal consistency or conceptual coherence of the instrument.

3.5. Ethical Considerations

Participation in the survey was voluntary. We obtained the participants’ consent at the beginning, after having explained the purpose of the research. We informed the participants that participation was anonymous and that they could withdraw at any point. No personally identifiable information (PII) was collected. All data were reported in aggregate form to ensure confidentiality.

4. Results

4.1. Socio-Demographic Profile of Participants

The majority of 131 participants identified as female (96; 73.3%), followed by male (28; 21.4%). A small number (5; 3.8%) preferred not to disclose their gender, and two (1.5%) identified with a different gender category (“other”). The respondents were primarily students of English Studies (91; 69.5%) and Translation Studies (37; 28.2%), with three Erasmus exchange students (2.3%) also participating.

Regarding the level of study, the largest group were first-year undergraduate (BA) students (46; 36.0%), followed by second-year (28; 21.9%), and third-year BA students (20; 15.6%), then second-year MA (19; 14.8%), and first-year MA students (11; 8.6%). Four participants (3.1%) were recent MA graduates (Slov. absolvent), while no recent BA graduates responded.

In terms of residence, 48 students (approx. 36.6%) reported living in rural environments, and 34 (26%) in urban areas. An additional 31 students (23.7%) selected environments “more rural than urban,” and 18 students (13.7%) settings “more urban than rural.”

When asked about the reliability of their internet connection, 52 students (39.7%) described their internet as fully reliable, and 69 (52.7%) as considerably reliable. Only ten students (7.6%) reported unreliable internet, and none reported having no access.

Students reported high levels of access to digital devices. Smartphones were the most common (123; 93.9%), followed closely by laptops (120; 91.6%). Tablets were used by 51 students (38.9%), desktop computers by 35 (26.7%), and smartwatches by 13 (9.9%). Only one student (0.8%) reported having no access to any of these devices.

4.2. General Digital Habits and Awareness

Most students expressed strong support for the role of digital tools in academic learning. Specifically, 92.4% of respondents (121) either agreed or strongly agreed that digital tools were useful for learning a language, while 87.8% (115) reported that these tools were beneficial for studying linguistics, literature, and/or translation.

Self-assessment of digital competences was similarly positive. A total of 86.3% of students (113) agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that they are proficient in using modern digital tools for academic tasks. However, such self-perceptions may not always align with actual digital skills; prior studies (Selwyn, 2009; Sciumbata, 2020) argue that students often self-identify as digitally competent but fail to engage with discipline-specific digital practice, which was also observed in our survey results. There were no major differences between BA and MA students or between English or Translation students in expressing strong support for digital tools use in academic learning and self-assessment of digital tools proficiency.

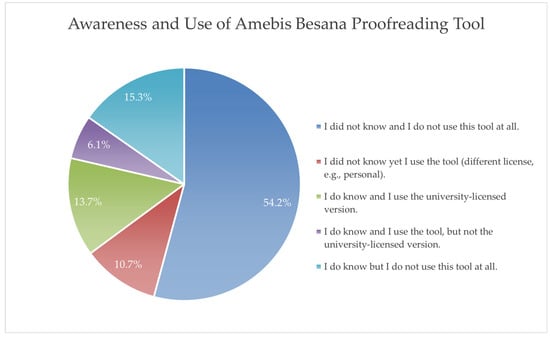

When asked about awareness and use of university-provided digital tools, students’ responses varied by tool. Among the most recognized and frequently used tools were Microsoft Word and PowerPoint, with 60.3% (79) and 61.1% of students (80) using the university-licensed versions. A further 24.4% (32) and 23.7% (31) used these programs, but not through the university. Outlook (94; 71.8%) and Microsoft Teams (99; 75.6%) also had high usage rates, along with Eduroam (92; 70.2%). Less commonly used tools included Foxit PDF Editor Pro (Foxit Software Inc., 2025) and the Slovenian-language automatic proofreading tool Amebis Besana (see Figure 1), as most students were unaware of their availability. Again, there were no major differences between BA and MA or English and Translation student responses in comparing the most frequently used tools, the only exception being the Amebis Besana proofreading tool, where 59% (55) of BA students were unaware that the university offers this tool, nor do they use it compared to 44% (15) of MA students, representing a reduction by a factor of 1.34 from BA to MA level. The results also differed between fields: 59% (54) of English Studies students do not know or use the tool compared to only 43% (16) of Translation students (a difference of a factor of 1.37). In line with this, more Translation Studies students use the tool through the university-provided license (19% (7), compared to 12% (11)) of the English Studies students. A further 16% (6) of Translation students use the tool, yet were unaware that the tool is offered by the university (compared to 9% (8) of English Studies students).

Figure 1.

Awareness and Use of the Slovenian-Language Proofreading Tool Amebis Besana.

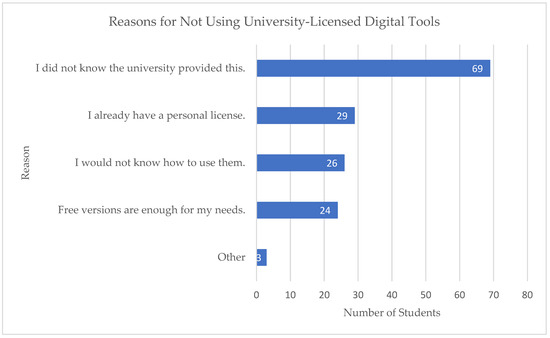

The most common reason cited for not using university-provided tools was a lack of awareness, selected by 69 students (52.7%). Other reasons they included in this multiple-choice question were as follows: already owning a personal license (29 students; 22.1%), not knowing how to use the tools (26 students; 19.8%), and finding free versions sufficient (24 students; 18.3%). Additionally, three students (2.3%) cited other reasons, such as not caring about the tools, not needing them personally, or having trouble with the setup process. These responses have been grouped under the category “Other” in Figure 2, which visualizes the main reasons students gave for not using university-licensed tools. In comparing undergraduate and graduate responses, a similar trend could be observed as in the Amebis Besana usage responses. Compared to BA students, fewer MA students reported being unaware the university provided the tools (41% (14) MA compared to 57% (54) BA students); that they would not know how to use the tools (9% (3) MA compared to 23% (22) BA students), and that the free versions suffice for their work (9% (3) MA compared to 22% (21) BA students). Moreover, MA students use the university-licensed tools in higher numbers than BA students (44% (15) MA compared to 30% (28) BA). There were no major differences between English and Translation students in this respect.

Figure 2.

Reasons for Not Using University-Licensed Digital Tools.

4.3. Use of Digital Tools for Language Learning

When asked about their use of digital tools specifically for language learning purposes, students generally reported a high appreciation for their effectiveness. A total of 72.5% (95) “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that grammar and language editing tools helped improve their writing. However, actual usage rates were significantly lower: only 34.4% (45) reported “always” using such tools for academic writing, and 22.9% (30) used them often. Among these, Grammarly was the most frequently recognized grammar and language editing tool. The remaining 42.7% (56) reported using them occasionally, rarely, or never. MA students reported slightly higher use than BA students (from 58% (51) at BA to 65% (22) at MA level), yet more of them also “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that grammar and language editing tools improved their writing (from 69% (65) to 79% (27)). A seemingly counterintuitive difference occurred between fields: only 65% (24) of Translation students “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that grammar tools improved their writing compared to 75% (68) of English Studies students, with only 46% (17) of them using grammar tools “always” or “often”, a considerable decrease compared to English Studies students (62% (56)).

A total of 113 out of 131 students (86.3%) reported that Microsoft Word was their primary word-processing software for academic writing. Google Docs was selected by 14 students (10.7%), while Notion and Apple Pages were each cited by one student (0.8% each); two students reported using other tools. Overall, 124 students (94.7%) indicated that they used word-processing software “always” or “often” for drafting, editing, and completing written assignments. There were no major differences between BA and MA students or between fields here.

Generative AI tools such as ChatGPT, Bing, and Bard were recognized by many students, but their integration into writing tasks was varied. According to the dataset, 14 students (10.7%) reported “always” using generative AI tools for writing tasks, and 29 students (22.1%) used them “often,” totaling 43 students (32.8%) who frequently relied on these tools for tasks such as paraphrasing, grammar checking, or generating ideas. An additional 30 students (22.9%) used generative AI tools occasionally, while 29 students (22.1%) used them rarely, and 29 students (22.1%) never used them at all. MA students reported increased use of generative AI tools (44% (15) compared to 28% (26) BA students), while Translation students and English Studies students utilize generative AI to a similar degree (approximately 32% (12 and 29 students, respectively)).

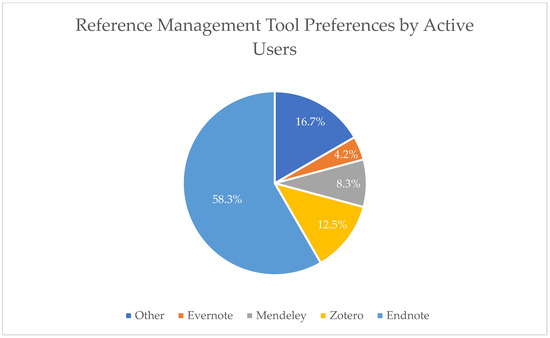

Students generally reported low engagement with reference management tools. Only 18.4% (24) indicated frequent use (selecting “always” or “often”), while a combined 66.4% (87) reported using them “rarely” or “never”. The situation slightly improves from BA to MA, with a 1.7 increase in use; nevertheless, the overall percentages remain very low, as only 14% (13) of all BA and 24% (8) of all MA students reported “always” or “often” using reference management software. There were no significant differences here between fields. Among the small group of active users of reference management software, EndNote emerged as the most often used (14 students; 10.7%), followed by Zotero (3 students; 2.3%), Mendeley (2 students; 1.5%), and Evernote (1 student; 0.8%). An additional four students mentioned other tools such as Mybib, Scribbr, or built-in citation features in word-processing software (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Reference Management Tool Preferences by Active Users.

4.4. Use of Academic Resources and Digital Literacy Practices

Regarding academic research practices, most students reported heavy reliance on general search engines. Platforms like Google, Microsoft Bing, and DuckDuckGo were used “always” or “often” by 110 students (84%). In contrast, only 37.4% (49 students) reported “always” or “often” using the university’s UM:NIK platform, with 38.9% (51 students) stating they “rarely” or “never” used it. MA students use the platform more often (from 33% (31) at BA to 53% (18) MA level), while the analysis showed no differences between fields.

Google Scholar emerged as the most frequently used academic research platform, with 43 students (32.8%) using it “always” and 36 (27.5%) “often.” JSTOR is “always” used by 27 students (20.6%) and “often” by 20 students (15.3%), but usage dropped significantly for more specialized databases: only two students (1.5%) reported using ProQuest “always”, and 2 (1.5%) “often,” while 106 students (80.9%) said they “never” used it. Similarly, Scopus is “always” used by just one student (0.8%) and “often” by 3 (2.3%), while 103 students (78.6%) reported never using it. Web of Science scored slightly better, with five students (3.8%) reporting it as “always” used and 11 (8,4%) “often,” yet 83 students (63.4%) still reported never having accessed it. MA students reported a significantly higher usage of JSTOR (from 26% (24) at BA to 65% (25) in MA students). Nevertheless, the overall usage of other academic research platforms (ProQuest, Scopus, and Web of Science) at both levels of study remains extremely low, used only by individual students. Between fields, results also show no differences in the usage of ProQuest, Scopus, or Web of Science; however, results for JSTOR show that 44% (40) of English Studies students use it “always” or “often” compared to only 16% (6) of Translation students, representing a significant deviation.

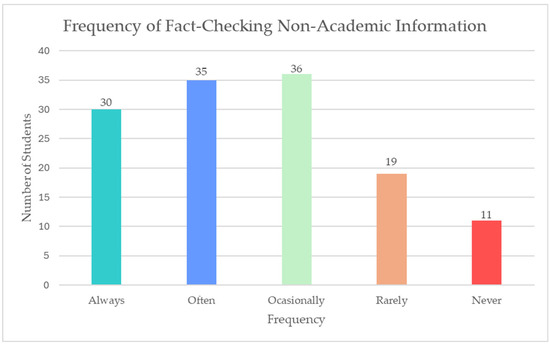

In terms of digital literacy and critical evaluation, student fact-checking practices for non-academic information, depicted in Figure 4, revealed a mixed picture. Only 30 students (22.9%) reported that they “always” verify the accuracy of information from sources such as blogs, Wikipedia, or social media, while 35 students (26.7%) said they did so “often.” The remaining 66 students (50.4%) indicated that they verified information only “occasionally,” “rarely,” or “never.” MA students reported better practices than BA students in this respect, with 65% (22) “always” or “often” fact-checking non-academic information (compared to 47% (44) of BA students). There were no differences between fields here.

Figure 4.

Frequency of Fact-Checking Non-Academic Information.

Among those who actively engage in fact-checking, commonly reported strategies included consulting academic sources, cross-referencing multiple websites, checking the reliability and credibility of the publication or platform, and reviewing the author’s credentials.

4.5. Non-Technical Challenges in Digital Learning

In addition to technical barriers, students identified several non-technical challenges that negatively affected their ability to effectively use digital tools in academic settings. Of the 36 (27%) students who reported facing such issues, 12 (9%) specifically highlighted limited access to academic materials, including full journal articles and e-books, as a major obstacle. These students described situations where they were only able to access abstracts or encountered content behind paywalls, resulting in frustration and difficulty completing academic tasks. For example, one student remarked: “University of Maribor doesn’t cover all of the paid resources, so I have to search a lot.”

Furthermore, concerns about information reliability and source credibility were a recurring theme. Several respondents mentioned uncertainty when using platforms like Google Scholar, particularly in the context of distinguishing between peer-reviewed and non-peer-reviewed content. This underuse may contribute to confusion about the trustworthiness of sources encountered online.

Students also expressed significant concern over the lack of structured guidance from the university or instructors regarding how to access and navigate institutional platforms. In open-ended responses, students repeatedly noted that while tools like UM:NIK or Moodle were available, they lacked training on how to use them effectively. Given that 42% of students rarely or never used UM:NIK, and over 60% never accessed major academic databases such as Scopus, Wiley, or Web of Science, the problem appears to be rooted less in access and more in awareness and skill gaps.

5. Discussion

The findings of this survey provide a nuanced picture of how students in the English and Translation Studies programs at the University of Maribor interact with digital tools in their academic and language learning routines. A major takeaway is the discrepancy between self-perceived proficiency and actual usage patterns. While 86.3% (113) of students considered themselves proficient with digital tools, their reported practices reveal more limited and selective engagement. The data confirm earlier concerns raised in the literature about students’ overestimation of their digital competence, while also highlighting structural gaps in awareness, training, and institutional support for digital tools (Ahmed & Roche, 2022; Yi & Wang, 2025). This also reinforces the notion that possession of digital capital, in the form of skills, knowledge, and access, does not automatically translate into its meaningful or strategic deployment for academic and language learning purposes.

To relate to the first RQ (awareness and engagement with digital tools), the survey revealed a considerable lack of awareness of the university-provided digital tools among students. The most frequently mentioned reason for non-use of Microsoft 365 apps, Foxit PDF Editor Pro, and automatic proofreading tools for Slovenian was simply that students were unaware that such tools are available—an issue also raised by Mokhtar et al. (2024) in the context of students’ information-seeking difficulties. Despite high general use of tools like Microsoft Word and PowerPoint, students were often unaware of their university-licensed versions. Notably, 52.7% (69) of respondents indicated they simply did not know the university provided at least one of the digital tools mentioned in the survey. This supports findings by Schilling et al. (2024), who emphasized that information about digital tools must be effectively communicated and accessible to impact student engagement and tool uptake. The situation improves at the MA level, with more students using the university-licensed tools in general, and with fewer reporting that they were unaware of the university offer (41% (14) versus 57% (54) at the BA level); that they would not know how to use the tools (9% (3) MA vs. 23% (22) at BA), or that the free versions suffice for their work (9% (3) MA vs. 22% (21) at BA). This could be explained by the fact that an MA student had more opportunities to come across the tools or the information about the university’s offer during their time at the university, or that their advanced work demanded additional effort on their part to seek out advanced versions of the tools. Nevertheless, although a greater share of MA students uses university-licensed tools compared to BA students, the overall numbers still show that, after studying for more than three years, fewer than half of MA students (44% (15)) use these tools, and that 41% (14) were unaware that the university provided them. This strongly suggests that the introduction of digital tools should be systematized.

Our second RQ focused on using digital tools for language studies and language learning. Perhaps the most striking finding here was the underutilization of grammar and editing tools, despite a strong belief in their effectiveness. While 72.5% (95) of students believed grammar and editing tools improve writing, only 57.3% used them “often” or “always”. Moreover, more than half the participants (71; 54.2%) were unaware of the university’s Slovenian proofreading tool Amebis Besana—an alarming statistic considering that most students are required to produce work in both English and Slovenian. This reflects not just a lack of awareness but a missed opportunity for improving multilingual academic writing through technology. While MA students reported higher usage (65% (22)) than BA students (58% (51)), a greater share of them also “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that grammar and language editing tools improved their writing (from 69% (65) at BA to 79% (27) at MA). The discrepancy between the reported usefulness of the tools and their actual usage, therefore, remained. Comparing the results between fields, a smaller proportion of Translation students believe that grammar tools improve their work (65% (68) compared to 75% (24)). Translation students also use grammar tools to a lesser extent (46% (17) to 62% (56)). On the other hand, Translation students utilize the Slovenian proof-reading tool (Amebis Besana) to a greater extent: a higher proportion of Translation students use the university-provided license (19% (7) compared to 12% (11)), and a greater share of Translation students (16% (6) compared to 9% (8) English Studies students) use the tool despite not knowing the university offers the license were unaware that the tool is offered by the university. How to explain this apparent anomaly?

One of the aspects in which the Translation Studies curriculum differs from the English Studies one is a stronger focus on the Slovenian language and grammar, with several courses dedicated to it throughout the study program. The teaching staff thus often mentions and encourages (critical) use of Amebis Besana, which could explain the discrepancy between English and Translation students in this respect and could imply that discipline-specific actions do affect adoption and usage of digital tools. While this explains the higher usage of the Slovenian proofreading tool, it fails to explain a lower confidence in and use of grammar and editing tools in general. The reason for the latter could be the nature of translation, where students find grammar and editing tools less useful for technical, financial, medical, and legal translation (since a tool like Grammarly flags the established discourse of the field and offers unusable stylistic “improvements,” such as clarity or delivery), especially when translating into a foreign language (English). On the other hand, more coursework submitted in the Slovenian language necessitates more frequent usage of the Amebis Besana proofreading tool, regardless of its lesser effectiveness. This anomaly might, therefore, not be a first or second language issue.

Students also reported low levels of engagement with generative AI tools in their studies, with only 32.8% (43) reporting using such tools “always” or “often.” Surprisingly, usage of such tools was higher in MA students (44% (15) compared to 28% (26), implying that “older” students are more proficient in this area, further substantiating the “digital native” myth about younger students (Selwyn, 2009). These findings also mirror concerns from Briggs (2018) and Al-Ali (2025), who highlight student skepticism about AI tools and a lack of training in how to use them meaningfully in multilingual and translation contexts.

Our third RQ focused on identifying the gaps in academic digital literacy, which turned out to be significant. Students relied overwhelmingly on general-purpose search engines such as Google or Microsoft Bing (used “always” or “often” by 84% (110) of respondents), while far fewer used specialized academic resources. For example, 90.1% (118) of students “rarely” or “never” used ProQuest, and only 31.3% (41) used UM:NIK consistently. While MA students used JSTOR more often (from 26% (24) at BA to 65% (25) at MA), the overall usage of other academic research platforms (ProQuest, Scopus, and Web of Science) remained low at both levels of study. The slightly higher usage at the MA level may be due to students having more opportunities during their studies to encounter these tools or learn about them, as well as to their more advanced academic needs. Between fields, there was a significant discrepancy in JSTOR use: 44% (40) of English Studies students reported using it “always” or “often,” compared to only 16% (6) of Translation students. We believe this could be owing to the staff at the English Department often recommending the usage of JSTOR, and occasionally also showcasing its use, which seems to translate into higher adoption and usage among English Studies students. This also demonstrates that greater exposure to the tool can result in greater tool adoption and usage.

Alongside the low usage of specialized academic resources, very few students also used reference management tools, with only 18.4% (24) using them “always” or “often,” and the situation is not improved significantly at the MA level, as only 24% (8) of all MA students use such tools “always” or “often.” The low adoption rate and limited diversity of tools open a broader issue of underexposure and insufficient guidance. The qualitative responses confirm that lack of training and confidence is a major barrier. One student explained, “They are hard to learn how to use,” while another noted, “…I am not yet proficient in using them, therefore I often cite articles manually.” This is especially concerning given the importance of reference management for academic writing tasks that involve engagement with source material, citation formatting, and bibliography organization.

These results suggest a clear trend: although students engage heavily with digital tools for academic work, their interaction with university-provided or specialized academic databases remains minimal. This points to a gap in either student awareness of available institutional resources or their training for and comfort in navigating them—both of which are prerequisites for the meaningful use of digital tools as defined earlier in this study.

Results also show a worrying trend regarding students’ fact-checking practices. Only 49.6% (65) “always” or “often” fact-check the accuracy of non-academic sources. MA students perform slightly better (65% (22)), suggesting that the incentive to promote critical thinking is somewhat effective, yet these numbers cannot be considered sufficient for the university-educated population. While the reported strategies for fact-checking, such as cross-referencing or authenticating source credibility, were appropriate (Yi & Wang, 2025), their low use implies a lack of structured training. Students may be tech-comfortable in general, but not necessarily tech-competent in academic contexts. Milošević (2022) provides a conceptual backbone for this argument: he asserts that today’s education must promote critical thinking, problem solving, collaboration, and creativity, complemented by digital literacy and information literacy. Our findings thus substantiate Milošević’s point: without targeted efforts to build academic digital literacy, students will continue to use digital tools superficially (for instance, Googling answers) rather than strategically (using databases, evaluating sources, leveraging advanced features). This emphasizes the need for more systematized integration of digital literacy skills, particularly those related to critical thinking, source evaluation, and academic research.

These trends thus imply a larger issue: students do not struggle with access, but with guidance. This was confirmed in the open-ended responses, where students expressed uncertainty about which tools to use, how to find credible academic content, and how to distinguish between reliable and unreliable information. Students are not digitally incompetent in principle, but they are navigating a fragmented and poorly scaffolded digital landscape. This aligns with findings by Sciumbata (2020), who argued that humanities students rate their skills as high while displaying significant gaps across the DigiComp framework.

Finally, students also identified non-technical challenges, including paywalls, restricted database access, and information overload. At UM, the tools may exist, but the infrastructure for their effective adoption appears fragmented. As Peterson and Finn (2024) note, institutional investment in digital infrastructure must be matched by support for training and integration, not left to faculty or students to navigate independently.

These results collectively point to a critical discrepancy between the availability of digital tools and students’ actual capacity to use them meaningfully and strategically—that is, a deliberate, goal-oriented, and critically informed way. The problem is not that tools do not exist—it is that students are unaware of them, untrained in their use, or unconvinced of their value. To address this, universities must design digital ecosystems that are not only technologically robust but also pedagogically intentional, inclusive, and student-centered. What is more, this calls for university-wide digital literacy frameworks that are consistent, inclusive, and tailored to students’ evolving needs (Ahmed & Roche, 2022). Similarly, Ravikumar et al. (2024) and Zheng and Kim (2025) argue that learning strategies, especially metacognitive self-regulation, are key to transforming digital access into competent, ethical, and independent tool use.

Finally, some limitations are to be considered. Given the non-probability sampling method and the focus on a specific field of study, the findings may not be directly generalizable to the entire student body at the University of Maribor. Additionally, since participation in the survey was voluntary, students with a stronger interest in or opinions about digital learning tools may have been more inclined to respond, potentially introducing bias toward certain viewpoints. Another limitation is the reliance on self-reported data, which may be affected by inaccuracies stemming from participants’ memory, perception, or desire to present themselves in a certain way.

6. Conclusions and Implications

This study, conducted at the University of Maribor, examined the perceptions and beliefs of the English and Translation students about their perception of and engagement with digital tools in academic and language learning contexts. While students generally express positive attitudes towards digital tools and report high confidence in their digital skills, the survey reveals a consistent gap between self-perception and actual usage, which is a finding detected in broader studies that critique assumptions about “digital natives” (Selwyn, 2009; Selwyn, 2022; Rodríguez et al., 2024).

The underutilization of university-provided tools, including reference management software and academic databases, points to structural issues related to tool awareness and usage (Ahmed & Roche, 2022; Alwerthan, 2025). The most common reported reason for not using the university-provided licenses was the unawareness of the university, and a total of 19.8% of students reported that they would not know how to use the tools anyway. Despite higher reported awareness and competence by MA students, 41% (14) remained unaware of the university’s offer at the graduate level. This strongly suggests that institutions ought to communicate the availability of digital tools and provide training in a systematic way.

The survey also revealed a disagreement between students’ recognition that digital tools are useful and their actual behavior. While grammar and language tools are widely regarded as useful by the majority, only 57.3% use them regularly. The discrepancy remains at the MA level—while students there report a higher usage, more of them also agree on their usefulness. Furthermore, over half the students were unaware of the automatic Slovenian proofreading tool Amebis Besana; surprisingly, Translation students used the tool more often than English Studies students, while reporting an overall lower grammar tools usage and usefulness. The reason could be (a combination of) more encouragement to use Amebis Besana at the Translation Department, the nature of translation, where such tools might be perceived as less useful for, e.g., technical or legal translations, or simply a higher share of coursework they need to submit in the Slovenian language. Students also report an unusually low use of generative AI across the board (less than a third), although MA students report slightly higher usage (less than half). This further highlights the need for systematic, formalized training on using generative AI for academic and language learning purposes.

The study reveals a major gap in the use of academic platforms: for their study purposes, students mostly rely on search engines like Google or Bing, and the majority practically never uses specialized academic resources or the university’s research platform UM:NIK. The only notable exception to this was the use of JSTOR, which was used by 26% of BA students and 65% of MA students. However, further analysis revealed that higher use of JSTOR is field-specific: only 6% of Translation students use it. We believe this can be attributed to the English Department staff, who often recommend and demonstrate its usage to students, further demonstrating that a higher adoption of specialized tools occurs when these are appropriately introduced to the students. Reference management tools are also rarely used (only 18.4%), and the situation does not improve notably at the MA level (24%). Similarly, we do not believe the reason to be student incompetence but rather a lack of exposure and formal training in this respect.

The study also showed that not enough students fact-check the accuracy of information required online (only 47% at the BA and 65% at the MA level); however, the reported fact-checking practices are appropriate. This again demonstrates that students are competent but require targeted and systematic efforts in areas like critical thinking, source evaluation, and research to become digitally literate. Open-ended responses further confirmed this, as students expressed uncertainty about which tools to use for finding credible academic content and distinguishing between reliable and unreliable information.

Finally, the study showed that students face non-technical challenges, like paywalls, restricted database access, and an overload of information. While the university has the necessary tools and infrastructure, it lacks the essential training in digital tools that would result in students utilizing these resources. This echoes the findings in Peterson and Finn (2024): institutional investment in digital infrastructure must be matched by support for training and integration, not left to faculty or students to navigate independently. Universities must design digital ecosystems that are not only technologically robust but also pedagogically intentional, inclusive, and student-centered.

The findings suggest that institutional efforts to support digital learning, while strategically aligned with European and global policy frameworks, have not yet been fully translated into consistent student engagement. As with the challenges identified in other higher education contexts, students of English and Translation studies at the UM often navigate digital learning environments without adequate training, guidance, or integration of tools into their curricula (Peterson & Finn, 2024; Pakaya, 2025).

In response to the findings, higher education institutions, especially those facing similar challenges, may consider several targeted actions. Introducing mandatory digital literacy orientation sessions for incoming students, particularly in writing- and research-intensive programs, can ensure a strong foundational skillset from the outset. Faculty should receive training and support to integrate digital tools into coursework in meaningful ways, helping students engage with these technologies in an academic context. To further support student development, writing and academic skills workshops should demonstrate the use of grammar checkers, citation tools, and academic search engines.

Ultimately, this research contributes new data on a population that has thus far been overlooked in digital education research: language-focused students at a regional Central and Eastern European institution. By focusing on a specific academic and institutional context, the case study adds a localized perspective to broader discussions on digital transformation and student digital literacy in higher education. The alignment of digital infrastructure with strategic communication and pedagogical support in institutions such as the University of Maribor may contribute to improved academic outcomes and better support students in navigating the increasingly digital academic and professional environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.L., T.O., T.T., J.U. and D.H.; Methodology, B.L., T.O., T.T., J.U. and D.H.; Software, T.T., J.U. and D.H.; Validation, B.L., T.O., T.T. and D.H.; Formal analysis, B.L., T.O., T.T., J.U. and D.H.; Investigation, B.L., T.O., T.T. and D.H.; Resources, B.L., T.O., T.T. and D.H.; Data curation, B.L., T.O., T.T., J.U. and D.H.; Writing – original draft, B.L. and D.H.; Writing – review & editing, T.O. and D.H.; Visualization, J.U. and D.H.; Supervision, B.L. and D.H.; Project administration, B.L. and D.H.; Funding acquisition, T.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted using a fully anonymous survey that did not involve the collection of personal or sensitive data, and participation was entirely voluntary. Following the decision of the faculty Ethics Committee, it was determined that ethical approval was not required for this research.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was not required for this study, as no personally identifiable or sensitive information was collected. The survey did not request names, contact details, or any other data that could reveal participant identities. All responses were collected in anonymized form.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article can be made available by the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

Jurij Urh was employed by the company Ledinek Engineering d.o.o. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ahmad, A., Zulfiqar, M., & Batool, B. (2024). Impact of technology on language learning: A study of translation apps and their usage at undergraduate level in university education. Journal of Social Sciences Review, 4(4), 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S., & Roche, T. (2022). Digital literacy and academic staff in an English medium instruction university: A case study. International Journal of Computer-Assisted Language Learning and Teaching (IJCALLT), 12(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akour, M., & Alenezi, M. (2022). Higher education future in the era of digital transformation. Education Sciences, 12(11), 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ali, A. (2025). The influence of AI on improving translation skills: A survey study. Wasit Journal of Humanities, 21(1), 919–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenezi, M. (2021). Deep dive into digital transformation in higher education institutions. Education Sciences, 11(12), 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Shihri, H. B. S. G., Mahfoodh, O. H. A., & Bin Mohd Ayub Khan, A. B. (2025). Examining the effect of the integration of multiple MALL applications on EFL students’ academic vocabulary acquisition: A mixed-methods study. Cogent Education, 12(1), 2473229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwerthan, T. (2025). Time efficiency as a mediator between institutional support and higher education student engagement during e-learning. PLoS ONE, 20(1), e0315420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amebis. (2025). Besana Avtomatska lektorica. Amebis. Available online: https://www.amebis.si/besana-predstavitev (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Anthropic. (2025). Claude. Anthropic. Available online: https://www.anthropic.com/claude (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Bahari, A., Han, F., & Strzelecki, A. (2025). Integrating CALL and AIALL for an interactive pedagogical model of language learning. Education and Information Technologies, 30, 14305–14333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavides, L. M. C., Tamayo Arias, J. A., Arango Serna, M. D., Branch Bedoya, J. W., & Burgos, D. (2020). Digital transformation in higher education institutions: A systematic literature review. Sensors, 20(11), 3291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobkina, J., Baluyan, S., & Dominguez Romero, E. (2025). Tech-enhanced vocabulary acquisition: Exploring the use of student-created video learning materials in the tertiary-level EFL (english as a foreign language) flipped classroom. Education Sciences, 15(4), 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boh Podgornik, B., Dolničar, D., Šorgo, A., & Bartol, T. (2016). Evaluation of information literacy of Slovenian university students. In S. Kurbanoglu, J. Boustany, S. Špiranec, E. Grassian, & D. Mizrachi (Eds.), Information literacy: Moving toward sustainability. ECIL 2015 (vol. 552, pp. 499–508). Communications in Computer and Information Science. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bologna Follow-Up Group (BFUG). (2020). Rome ministerial communiqué. European Higher Education Area. Available online: https://ehea2020rome.it/storage/uploads/5d29d1cd-4616-4dfe-a2af-29140a02ec09/BFUG_Final_Draft_Rome_Communique-link.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241–258). Greenwood. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. (1996). Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste (8th ed.). Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Briggs, N. (2018). Neural machine translation tools in the language learning classroom: Students’ use, perceptions, and analyses. The JALT CALL Journal, 14(1), 59–76. [Google Scholar]

- Burgos, M. V., & Anthony, J. E. S. (2024). Digital literacy and language learning: The role of information technology in enhancing English proficiency. American Journal of Education and Technology, 3(4), 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y., & Zhang, L. J. (2023). Effects of mobile-supervised question-driven collaborative dialogues on EFL learners’ communication strategy use and academic oral English performance. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1142651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calderón Gómez, D. (2021). The third digital divide and Bourdieu: Bidirectional conversion of economic, cultural, and social capital to (and from) digital capital among young people in Madrid. New Media & Society, 23, 2534–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deen, A., & Mahmoud, M. (2025). Instructional technology and learning English as a foreign language (EFL): Insights into digital literacy from Saudi environment. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 15(2), 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deep, P. D., Martirosyan, N., Ghosh, N., & Rahaman, M. S. (2025). ChatGPT in ESL higher education: Enhancing writing, engagement, and learning outcomes. Information, 16(4), 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-García, V., Montero-Navarro, A., Rodríguez-Sánchez, J.-L., & Gallego-Losada, R. (2023). Managing digital transformation: A case study in a higher education institution. Electronics, 12(11), 2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolenc, K., Šorgo, A., & Ploj Virtič, M. (2021). The difference in views of educators and students on Forced Online Distance Education can lead to unintentional side effects. Education and Information Technologies, 26(6), 7079–7105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooly, M. (2007). Joining forces: Promoting metalinguistic awareness through computer-supported collaborative learning. Language Awareness, 16(1), 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsevier. (2025). Scopus. Elsevier. Available online: https://www.scopus.com (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- European Commission, Directorate-general for education, youth, sport and culture. (2023). Digital education action plan 2021–2027: Improving the provision of digital skills in education and training. Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/33b83a7a-ddf9-11ed-a05c-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Feng, J., Yu, B., Tan, W. H., Dai, Z., & Li, Z. (2025). Key factors influencing educational technology adoption in higher education: A systematic review. PLoS Digital Health, 4(4), e0000764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferjan, M., & Bernik, M. (2024). Digital competencies in formal and hidden curriculum. Organizacija, 57(3), 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foxit Software Inc. (2025). Foxit PDF Editor Pro. Foxit Software Inc. Available online: https://www.foxit.com/pdf-editor (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Gerlich, M. (2025). AI tools in society: Impacts on cognitive offloading and the future of critical thinking. Societies, 15(1), 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkrimpizi, T., Peristeras, V., & Magnisalis, I. (2023). Classification of barriers to digital transformation in higher education institutions: Systematic literature review. Education Sciences, 13(7), 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkrimpizi, T., Peristeras, V., & Magnisalis, I. (2024). Defining the meaning and scope of digital transformation in higher education institutions. Administrative Sciences, 14(3), 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]