Co-Teaching as a Dynamic System to Support Students with Disabilities: A Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Co-Teaching in the Literature

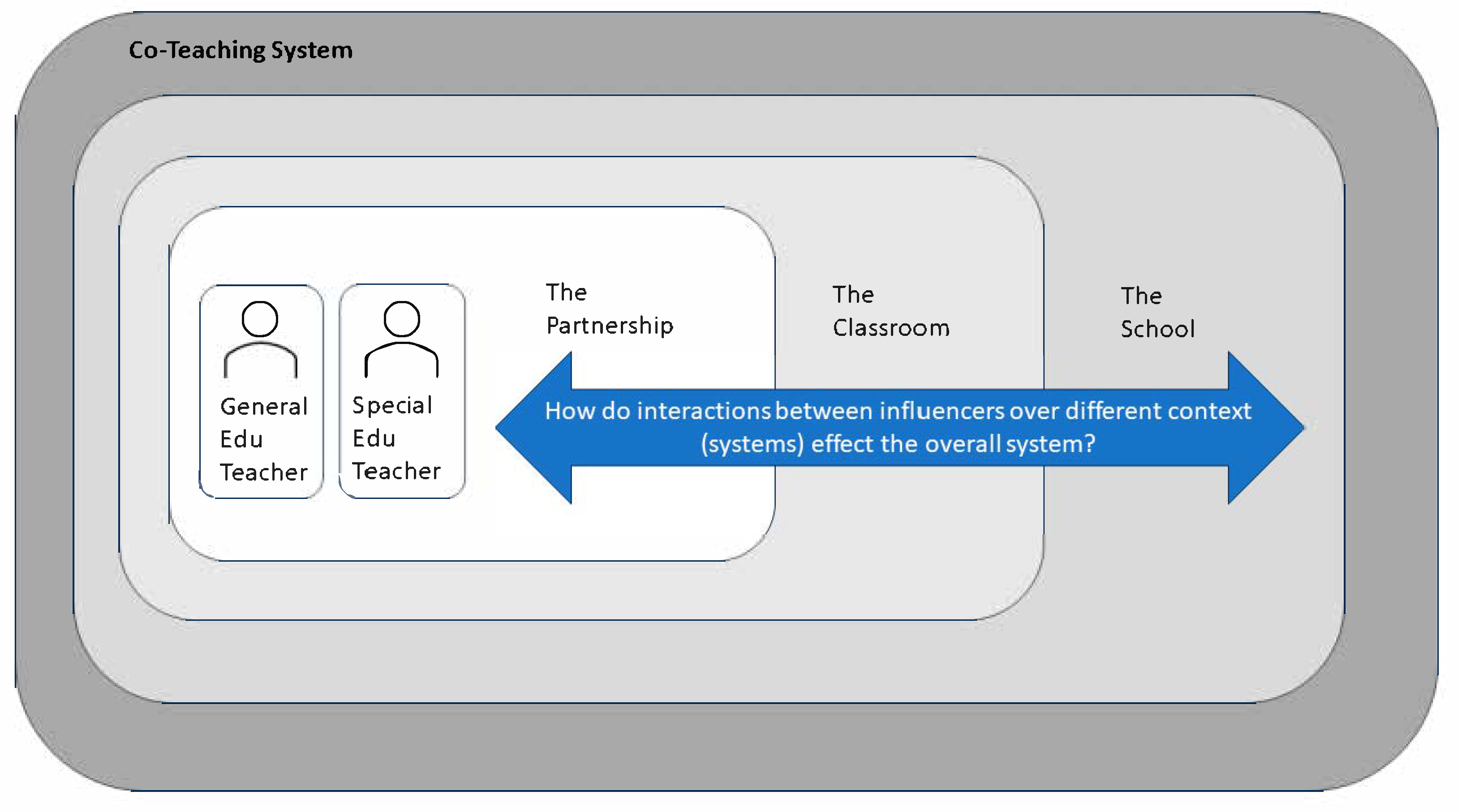

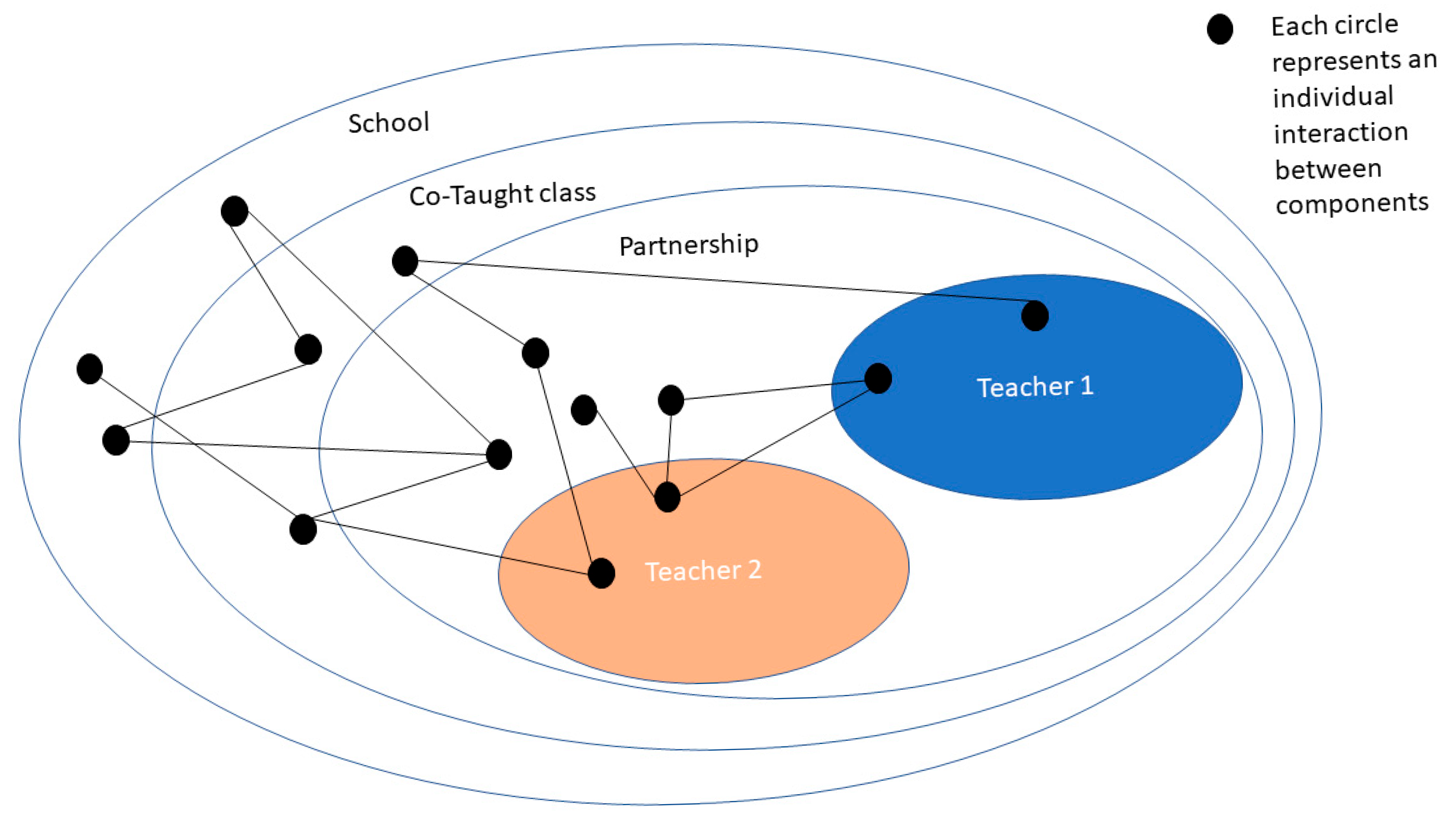

1.2. Dynamic Systems Theory

1.3. The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Positionality

2.2. Ethical Considerations and Trustworthiness

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Setting and Participants

2.5.1. Partnership 1: Mark and Bethany

2.5.2. Partnership 2: Lynn and Amy

3. Findings

3.1. Components of the System and the Effects

3.1.1. Level 1: Individual Teacher

…she [Bethany] is an expert in special education and knows exactly individuals learning difficulties or learning problems… while I read the IEP, she’s more versed in what works. I think I’m more on the math side where I know where the problems are for kids grabbing content or making connections with content.

I’ve [Amy] had a very, very unusual co teaching experience, because it’s always been positive, has always been amazing. Some people are not, [they are] never welcomed in the room. They’re handed copies, so they’re told to go make copies. They don’t have any input on anything.

3.1.2. Level 2: Co-Teaching Partnership Components

In hindsight, I wish she [Bethany] would have been along for the course planning the other math PLC [professional learning community] teacher and I did last year. I think when we were making the plan I [Mark] wasn’t thinking about how I would do this as a co teacher. We [Mark and Bethany] probably should have planned ahead for some of those activities.

They [math department] have the algebra PLC. In general, they had planned out last year, like, the timeline and everything. So he [Mark] already has that set. But we’ll talk almost daily about like, should we get rid of this part? Should we do this instead? You know, second block didn’t really get this part so fourth block, should we change it up this way? So we definitely plan and talk about it every day.

3.1.3. Level 3: Classroom Components

3.1.4. Level 4: School-Level Components

You get a good pairing and you leave it… you have the allowance in the master schedule to identify a good thing and keep it going. With that same allowance, you identify a bad thing and you abandon it and you fix it.

4. Discussion

4.1. Duration of the System

4.2. Instructional Decision-Making

4.3. Co-Teaching as a Dynamic System

4.4. Implications for Practice and Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SWDs | Students with disabilities |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Code | Definition | Interview Transcript Example |

|---|---|---|

| Components of Co-teaching | This category of coding brings together what each teacher identified as components of their co-teaching experience. These could be daily components, expectations of the school, prior experiences of the individual, and responsibilities of the individual. | |

| a. Individual teacher | Aspects that the individual teacher brings to the co-teaching system (ex.: prior experience, beliefs) | …we work together, but I think we are still learning about each other’s individual strengths and weaknesses, or we don’t want to step on each other’s toes in the process. So best of intentions to be equals. But we’re not quite there yet in the execution. |

| b. Partnership | Aspects of the co-teaching system that involve both teachers working together | She (the special education teacher) moved into the classroom at the end of the year, last year. And immediately we kind of started talking about like, how do we run that class? What’s important to you? What’s important to me? I think both of our concerns were, you know, this is what’s been successful with for the students. |

| c. Class | The classroom-level components that effect the system (ex.: class size, content) | It is different, because I’ve been in both. And last year, I was in math and English. And the way that we worked was just different depending on the subject. |

| d. School | The school expectations that play a role in the co-teaching system (ex.: teacher duty, planning blocks, assigning classes) | Yes, we have co-planning. Yeah, it’s (co-planning) super great. Yeah. There was one year that I co taught with someone, I can’t remember who and we did not have the same planning. It was just really hard to like touch base, and I would walk in, and then she would change the plans |

| Effects of the components | This coding category brings together how different co-teaching components affect how their system functions. This coding reveals the results of the different parts of co-teaching. | |

| a. Communication | How is communication affected by components of the system? | In hindsight, I wish she would have been along for the course planning that the other math PLC teacher and I did last year. I think when we were making the plan with the other math teacher or making the course plan, I wasn’t thinking about how would I do this as a co-teacher |

| b. Time in class | How does the system affect the amount of time a teacher is in class? | So like, with the other special education teacher, he was my co-teacher from one of the class periods. And, but he was never in the class, because he was doing that administrative kind of like trying to be an administrator. So he was never really present in the class. |

| c. Instructional choices | How does the system play a role in instructional choices? | “So you would think that, you’re saying that, the longevity of it makes a difference?” It’s a huge difference. And the other thing that makes a difference is not just the partnership with the person. But that I’ve been in English for six years so I have content knowledge. I’ve done it seven different ways with seven different people and everyone had a different approach. So I can think of that, planning wise, and give that input |

| Components needed for a successful system | This category establishes what the participants believe is necessary for a successful system. Some responses in this code are also coded in the general components category. | |

| a. Necessary elements for a successful system | What supports or elements must be in place or considered (e.g., external influencers) | “you get a good pairing and you leave it yeah, don’t mess with it. you have the allowance in the master schedule, to identify a good thing and keep going” |

Appendix A.2

- How long have you been working with your co-teaching partner?

- Co-teaching is a fully collaborative experience, as I am sure you know, I was hoping you could describe your partner’s role in planning and teaching for your co-taught class?

- Could you also describe your role in planning and teaching the class?

- Does the process you just described differ from your planning for a “solo” taught class?

- What is a strength of your co-teaching implementation? What is an area of growth?

- Which of the six would you say you are most familiar with?

- Which of the six would you say you are least familiar with?

- Now that you have read a little about each one, can you share with me how you think each method could be used or why you think it could not be used in your instruction? (If you have used a method, can you share with me how you have done that?)

- Let’s review the photo you shared with me that represents your experience with co-teaching, can you share some insight about why you selected this photo?

- Imagine the perfect co-teaching world, what does that entail?

References

- Bessette, H. J. (2008). Using students’ drawings to elicit general and special educators’ perceptions of co-teaching. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24(5), 1376–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottge, B. A., Cohen, A. S., & Choi, H. J. (2018). Comparisons of mathematics intervention effects in resource and inclusive classrooms. Exceptional Children, 84(2), 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brantlinger, E., Jimenez, R., Klingner, J., Pugach, M., & Richardson, V. (2005). Qualitative studies in special education. Exceptional Children, 71(2), 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burks-Keeley, R. G., & Brown, M. R. (2014). Student and teacher perceptions of the five co-teaching models: A pilot study. Journal of the American Academy of Special Education Professionals, 149, 185. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2016). Thematic analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(3), 297–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colson, T., Xiang, Y., & Smothers, M. (2021). How professional development in co-teaching impacts self-efficacy among rural high school teachers. The Rural Educator, 42(1), 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, L., & Friend, M. (1995). Co-teaching: Guidelines for creating effective practices. Focus on Exceptional Children, 28(3), 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Friend, M. (2015). Welcome to co-teaching 2.0. (general and special education integration to achieve the goals of individualized education program). Educational Leadership, 73(4), 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Grenier, M. A. (2011). Coteaching in physical education: A strategy for inclusive practice. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 28(2), 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haggis, T. (2008). ‘Knowledge must be contextual’: Some possible implications of complexity and dynamic systems theories for educational research. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 40(1), 158–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, Q., & Rabren, K. (2009). An examination of co-teaching: Perspectives and efficacy indicators. Remedial and Special Education, 30(5), 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IDEA. (2004). Individuals with disabilities education act of 2004, 20 USC 1400 (IDEA). Available online: http://idea.ed.gov/download/statute.html (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Keeley, R. G., Brown, M. R., & Knapp, D. (2017). Evaluation of the student experience in the co-taught classroom. International Journal of Special Education, 32(3), 520–537. [Google Scholar]

- King-Sears, M. E., Jenkins, M. C., & Brawand, A. (2020). Co-teaching perspectives from middle school algebra co-teachers and their students with and without disabilities. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 24(4), 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King-Sears, M. E., Stefanidis, A., Berkeley, S., & Strogilos, V. (2021). Does co-teaching improve academic achievement for students with disabilities? A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 34, 100405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losinski, M., Sanders, S., Parks-Ennis, R., Wiseman, N., Nelson, J., & Katsiyannis, A. (2019). An investigation of co-teaching to improve academic achievement of students with disabilities: A meta-analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Special Education Professionals, 149, 170. [Google Scholar]

- Magiera, K., & Zigmond, N. (2005). Co-teaching in middle school classrooms under routine conditions: Does the instructional experience differ for SWD in co-taught and solo-taught classes? Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 20(2), 79–85. [Google Scholar]

- McLeskey, J., Barringer, M.-D., Billingsley, B., Brownell, M., Jackson, D., Kennedy, M., Lewis, T., Maheady, L., Rodriguez, J., Scheeler, M. C., Winn, J., & Ziegler, D. (2017). Council for exceptional children, & collaboration for effective educator development, accountability and reform. In High-leverage practices in special education. Council for Exceptional Children. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, M. L., & Caniglia, J. (2018). Co-teacher noticing: Implications for professional development. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 22(12), 1345–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moin, L. J., Magiera, K., & Zigmond, N. (2009). Instructional activities and group work in the US inclusive high school co-taught science class. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 7(4), 677–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murawski, W. W. (2006). Student outcomes in co-taught secondary English classes: How can we improve? Reading & Writing Quarterly, 22(3), 227–247. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services. (2022). 44th annual report to congress on the implementation of individuals with disabilities education act. U.S. Department of Education. Available online: https://sites.ed.gov/idea/annual-reports-to-congress/ (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Packard, A. L., Hazelkorn, M., Harris, K. P., & McLeod, R. (2011). Academic achievement of secondary students with learning disabilities in co-taught and resource rooms. Journal of Research in Education, 21(2), 100–117. [Google Scholar]

- Pancsofar, N., & Petroff, J. G. (2016). Teachers’ experiences with co-teaching as a model for inclusive education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 20(10), 1043–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, W. J., Weiss, M. P., & Ismail, H. A. (2021). Defining specially designed instruction: A systematic literature review. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 36(2), 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, J. M. (2015). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Stemler, S. (2001). An overview of content analysis. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 7(1), 17. [Google Scholar]

- Strogilos, V., & King-Sears, M. E. (2019). Co-teaching is extra help and fun: Perspectives on co-teaching from middle school students and co-teachers. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 19(2), 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strogilos, V., King-Sears, M. E., Tragoulia, E., Voulagka, A., & Stefanidis, A. (2023). A meta-synthesis of co-teaching students with and without disabilities. Educational Research Review, 38, 100504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strogilos, V., Stefanidis, A., & Tragoulia, E. (2016). Co-teachers’ attitudes towards planning and instructional activities for students with disabilities. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 31(3), 344–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strogilos, V., & Tragoulia, E. (2013). Inclusive and collaborative practices in co-taught classrooms: Roles and responsibilities for teachers and parents. Teaching and Teacher Education, 35(1), 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strogilos, V., Tragoulia, E., & Kaila, M. (2015). Curriculum issues and benefits in supportive co-taught classes for students with intellectual disabilities. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 61(1), 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thelen, E. (2005). Dynamic systems theory and the complexity of change. Psychoanalytic Dialogues, 15(2), 255–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurmond, V. A. (2001). The point of triangulation. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 33(3), 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremblay, P. (2013). Comparative outcomes of two instructional models for students with learning disabilities: Inclusion with co-teaching and solo-taught special education. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 13(4), 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Office of Civil Rights Data Collection. (2020). View state profiles. Available online: https://civilrightsdata.ed.gov/view (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Weiss, M. P., & Rodgers, W. (2020). Instruction in co-taught secondary classrooms: An exploratory case study in algebra 1. Journal of the American Academy of Special Education Professionals, 119, 133. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R. K. (2018). Case study research and applications (Vol. 6). Sage. [Google Scholar]

| Model | Visual | Description |

|---|---|---|

| One Teach/One Observe |  | One teacher is the lead of whole group’s instruction while the other teacher is observing students. The teacher observing is gathering data on an individual student, group, or the whole class. |

| One Teach/One Assist |  | One teacher is the lead of whole group’s instruction while the other teacher moves around the room to support individual student needs. Some examples of what the assisting teacher could be doing are answering questions, briefly reteaching a concept, and keeping students on task. |

| Parallel Teaching |  | The class is divided into two groups, with one teacher working with a group. Students can be grouped by academic need or just to reduce the student-to-teacher ratio for instruction. Teachers could be working on the same activity with both groups or providing instruction in a different way for differing academic needs. |

| Station Teaching |  | Teachers group students to complete learning activities in different stations. The teachers can lead the learning in a specific station, as well as monitor independent student work. Students can be grouped by academic need. Students rotate to different stations either when they have completed the activity or after a specified amount of time. |

| Alternative Teaching |  | While most students stay in a whole-group setting, a small group is assigned to the other teacher to engage in different instruction. This small-group work could include activities like reteaching, accommodated assessment, or previewing upcoming instruction. |

| Team Teaching |  | In whole group’s instruction, both teachers lead portions of the direct instruction. Both teacher’s contributions on instruction are integrated throughout the lesson. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qualls, L.W.; Arastoopour Irgens, G.; Hirsch, S.E. Co-Teaching as a Dynamic System to Support Students with Disabilities: A Case Study. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 733. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060733

Qualls LW, Arastoopour Irgens G, Hirsch SE. Co-Teaching as a Dynamic System to Support Students with Disabilities: A Case Study. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(6):733. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060733

Chicago/Turabian StyleQualls, Logan W., Golnaz Arastoopour Irgens, and Shanna E. Hirsch. 2025. "Co-Teaching as a Dynamic System to Support Students with Disabilities: A Case Study" Education Sciences 15, no. 6: 733. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060733

APA StyleQualls, L. W., Arastoopour Irgens, G., & Hirsch, S. E. (2025). Co-Teaching as a Dynamic System to Support Students with Disabilities: A Case Study. Education Sciences, 15(6), 733. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060733