Abstract

Inclusive education in early childhood is pivotal for fostering equitable learning opportunities and promoting diversity from a young age. Administrators play a key role in implementing inclusive practices effectively within educational settings. This systematic review synthesizes the attitudes of early childhood education administrators towards inclusion, examining how these attitudes influence the successful integration of inclusive practices and identifying the factors that impact these perspectives. A total of 18 studies were identified through a systematic search procedure and included in this review. The results reveal a generally positive attitude towards inclusion among administrators, tempered by notable challenges, such as insufficient training and inadequate resources. These challenges align with variations in administrators’ readiness to implement inclusive practices. This review also highlights variability in how administrators perceive their roles in inclusive education, ranging from instructional leaders to supportive facilitators. Although some studies identified influencing factors, such as gender, education level, and school location, these were more strongly associated with overall attitudes towards inclusion rather than role perception specifically. The implications for policy involve strengthening resource allocation and training for administrators to support inclusive practices effectively. For practice, there is a need to develop robust support structures and targeted professional development programs that address the specific needs of administrators in fostering inclusivity. Future research should expand to include diverse global perspectives and explore the nuances of administrative roles in different cultural and educational settings.

1. Introduction

Inclusive education is founded on the principle of providing equitable educational opportunities for all students, regardless of their abilities or disabilities, within mainstream classroom settings (Florian, 2012). Inclusion, in the context of early childhood, signifies a commitment to the principles, policies, and actions that uphold the entitlement of every infant and young child, along with their family, to engage fully in a diverse array of activities and environments as valued contributors to families, communities, and society (Balikci, 2025). The ultimate goals of inclusive experiences for both children with and without disabilities and their families encompass fostering a sense of belonging, cultivating positive social connections and friendships, and facilitating holistic development and learning to enable each child to achieve their maximum potential (DEC/NAEYC, 2009).

This approach fosters a collaborative and supportive environment that adapts to the diverse needs of all learners, promoting access to high-quality education and facilitating social, emotional, and academic development (Ainscow & Miles, 2008). Early childhood education, in particular, benefits significantly from inclusive practices as they lay the foundation for children’s lifelong learning and social development, influencing their attitudes towards diversity throughout their educational journey (Balikci, 2025; Black-Hawkins et al., 2007; Ostrosky et al., 2006).

While there has been progress in implementing inclusive education in early childhood settings, significant challenges persist (Alquraini, 2011). Resource constraints remain a common barrier to effective inclusion (Ravet & Mtika, 2024). Schools often struggle with insufficient funding to provide necessary materials, specialized equipment, or support staff, such as special education teachers and aides (Steed et al., 2024). The lack of funding can impede schools’ ability to make necessary modifications to facilities and classrooms, as well as hinder the availability of training for staff on inclusive practices (Ferguson, 2008). Moreover, the limited availability of training programs for educators and administrators presents another hurdle. Without proper training, teachers and school leaders may lack the confidence or expertise needed to adapt instruction to meet the diverse needs of all students (Balikci, 2025; Russell et al., 2023). This lack of preparedness can perpetuate resistance to change and limit the successful integration of inclusive education. Acceptance of inclusive practices also varies across early childhood settings. Some educators and administrators may hold misconceptions about the benefits of inclusion, such as concerns about negative impacts on students without disabilities or doubts about whether students with disabilities can achieve the same outcomes as their peers (Odom et al., 2011). These attitudes can hinder the widespread adoption of inclusive education.

Furthermore, there is ongoing debate within the field regarding the best approaches to inclusion. Finding the right balance between full inclusion and specialized support for students with more significant needs can be challenging (Winter & O’Raw, 2010). Determining the most effective methods of supporting diverse learners while also maintaining an inclusive environment requires thoughtful consideration and collaboration among educators, administrators, and policymakers (Slee, 2011). Despite these obstacles, there is a growing commitment to creating more inclusive early childhood educational environments (Loreman et al., 2011).

While inclusive education is often understood as encompassing various learner characteristics, including disability, language background, socioeconomic status, and cultural identity, this systematic review specifically focuses on inclusion in relation to disability. This focus reflects the scope of the existing research and aligns with our aim to understand how early childhood administrators perceive and support disability-related inclusion. Their leadership is essential in shaping inclusive environments, guiding teacher practice, and ensuring effective implementation of inclusive policies (Balikci & Bayrakdar, 2024).

In this context, an administrator is defined as an individual who holds a leadership or managerial role in a program, center, institution, or school, with responsibilities for overseeing operations, policies, and resource allocation (Starratt, 2003). For this review, administrators include directors, principals, or associate directors working in early childhood education settings, such as preschools, kindergartens, and childcare centers. These professionals are central to setting the tone for inclusive practice across diverse service types.

Early childhood administrators are instrumental in actualizing inclusive education within their institutions. They hold the authority to shape and guide school culture, which includes implementing policies that prioritize inclusive practices, allocating resources effectively, and supporting ongoing professional development for educators (Steed et al., 2024). By setting clear expectations and providing necessary backing, administrators can empower teachers to integrate inclusive practices into their classrooms and create an environment conducive to learning for all students (Rakap, 2024; Sakız et al., 2023). Moreover, administrators’ perspectives and attitudes towards inclusive education play a crucial role in influencing the overall commitment to and success of inclusion initiatives (Avramidis & Norwich, 2002). Positive attitudes and proactive support from leadership can lead to meaningful change, fostering an educational environment that embraces diversity and addresses students’ individual needs (Pijl & Meijer, 1997). Conversely, a lack of support or reluctance to fully embrace inclusive education may hinder the successful implementation of inclusion initiatives, potentially limiting students’ opportunities for success. Thus, understanding administrators’ attitudes towards inclusive education is essential for identifying areas for improvement and promoting effective inclusive practices (Florian & Black-Hawkins, 2011; Steed et al., 2024).

Several studies have indicated that attitudes predict or correlate with changes in behavior (e.g., Glasman & Albarracín, 2006; Kraus, 1995; Stangor, 2014). For instance, research has shown that teachers’ positive attitudes towards inclusive education are linked to the successful implementation of inclusive practices (Avramidis & Norwich, 2002; De Boer et al., 2010; Rakap & Kaczmarek, 2010). Similarly, administrators’ supportive attitudes can lead to a more effective allocation of resources, better training programs, and a more inclusive school culture (Balikci, 2025; Pijl & Meijer, 1997). Understanding administrators’ attitudes towards inclusion can help identify areas where additional support, training, or resources are needed to enhance the effectiveness of inclusion efforts.

Currently, there is a growing body of individual studies that investigate administrators’ attitudes towards inclusion in early childhood settings (Buell et al., 1999). These studies provide valuable insights into how administrators perceive inclusive education and the obstacles they face in implementing it. However, the literature lacks a systematic review synthesizing these findings, leaving a gap in our understanding of the broader trends and factors shaping administrators’ perspectives on inclusion. While the existing literature includes several reviews of teachers’ (Avramidis & Norwich, 2002; Lautenbach & Heyder, 2019; Van Steen & Wilson, 2020), parents’ (De Boer et al., 2010), and children’s (De Boer et al., 2012; Freer, 2023) perceptions and attitudes towards inclusion, there is a noticeable absence of reviews that focus specifically on administrators’ attitudes and perceptions in the early childhood education field.

The purpose of this systematic review is to synthesize early childhood administrators’ attitudes towards inclusion and explore the factors that influence these attitudes. By synthesizing the existing research, this review aims to contribute valuable insights that can inform future policies, training, and improvements in practice to foster inclusion in early childhood settings. This review is guided by the following research questions: (1) What are the descriptive characteristics of studies investigating attitudes of early childhood administrators towards inclusion? (2) What is the quality of studies included in this review? (3) What are the attitudes of early childhood administrators towards inclusion?

2. Method

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

Studies were included in this systematic review if they: (1) examined attitudes or perceptions of early childhood education administrators (such as principals, leaders, directors, schoolmasters) towards inclusion, (2) involved administrators from preschool, kindergarten, or early childhood centers, (3) reported original research data, (4) were published in peer-reviewed journals or as theses/dissertations, and (5) were available in English. Studies evaluating administrators’ attitudes alongside other stakeholders, like teachers, were considered if they provided specific data for administrators.

2.2. Search Procedures and Results

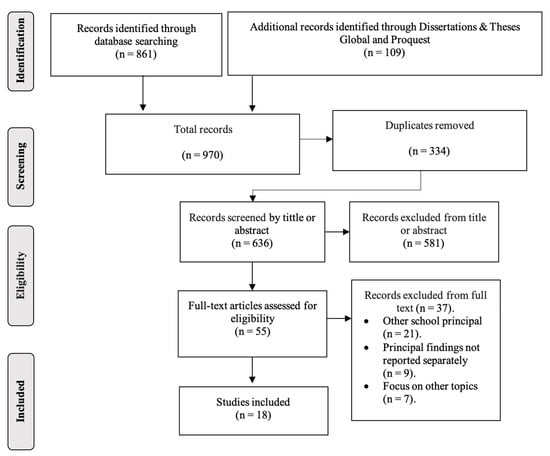

The search, conducted in February 2024, spanned several databases, including Academic Search Complete, Educational Resources Information Center, Education Full Text, PsychINFO, Scopus, Web of Science, Dissertations & Theses Global, and Proquest. The search terms included combinations of keywords related to educational leadership and attitudes, such as “principal,” “leader,” “administrator,” “director,” “schoolmaster,” “preschool,” “kindergarten,” “early childhood,” “attitude,” “perception,” “opinion,” “inclusion,” and “inclusive education.” No time restrictions were applied, and filters were set to retrieve only peer-reviewed articles and English full-texts. The search yielded 970 records, which were narrowed down to 636 unique records after removing duplicates. The initial screening of titles and abstracts excluded 582 studies, leaving 55 for full-text review. Of these, 37 were excluded for various reasons, such as not focusing on early childhood or lacking specific administrator data. Eighteen studies met all inclusion criteria. The search results and process are visually summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Procedural steps for identifying studies included in this review.

Microsoft Excel was used throughout the review process to organize and manage all collected records. Excel spreadsheets were used to store retrieved studies, remove duplicates, and document inclusion and exclusion decisions during screening. Descriptive data coding and extraction were completed in Excel using a structured template. Thematic analysis of qualitative findings was performed manually, following line-by-line coding in Microsoft Word documents, and emerging codes and themes were then synthesized and organized in Excel. Quantitative findings were summarized using basic descriptive statistics in Excel. Quality appraisal scores from the MMAT were also recorded, calculated, and compared using Excel to ensure consistency and transparency across reviewers.

2.3. Descriptive Coding

A coding spreadsheet was utilized to systematically extract descriptive data from the studies deemed eligible for inclusion in this review. The variables included in the coding sheet encompassed (a) author(s), publication year, and country in which the study was conducted, (b) publication type (thesis/dissertation vs. research article), (c) research method utilized, (d) tool or measure employed for data collection, (e) data analysis strategy, (f) demographic information of study participants, including job title, age, gender, ethnicity, years of experience, (g) types of disabilities observed among children in the schools where the participants worked, (h) school type in which the participants worked, and (i) overall result concerning attitudes towards inclusion (i.e., positive, mixed, negative; see Table 1 for descriptive variables).

Table 1.

Descriptive features of studies.

2.4. Quality Assessment

To evaluate the methodological quality of the studies included in this review, we employed the 2018 version of the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT; Hong et al., 2018). The MMAT is designed to appraise studies using quantitative (randomized controlled, nonrandomized, and descriptive), qualitative, and mixed-methods approaches. The appraisal framework of the MMAT comprises twenty-five criteria—five for each of the five research designs—and two screening questions. While the screening questions were universal for all studies, five specific criteria were applied to each study based on its design. Each criterion was assessed as “yes,” “no,” or “cannot tell.” A final quality score was calculated by dividing the number of criteria met by five and then multiplying the result by 100 to express it as a percentage. The criteria varied based on the study design and addressed various aspects, such as research questions, sampling, data collection, and analysis. Study quality was categorized on a scale from 0% (indicating poor quality; no criteria met) to 100% (indicating excellent quality; all criteria met). Each study was independently assessed by the first two authors, and any discrepancies were resolved through discussion until a consensus was reached. We included all studies in our data analysis without exclusion based on the quality appraisal.

2.5. Coding Results for Administrator Attitudes Towards Inclusion

The qualitative data from the studies were analyzed using a two-step process. Initially, an initial code list was created by detailed line-by-line examination of the results sections in four articles, with the researcher annotating and highlighting key information (Miles et al., 2014). Subsequently, a constant comparative method (Strauss & Corbin, 1998) was used to code the remaining articles, adjusting and adding new codes as necessary. This iterative coding process culminated in the identification of overarching themes according to thematic analysis principles (Maxwell, 2013). Findings from studies utilizing quantitative methods were summarized separately. Findings of the mixed-method study were interpreted within the framework of both qualitative and quantitative data, as outlined above.

2.6. Inter-Rater Reliability

Inter-rater reliability (IRR) coefficients were calculated for screening, application of quality indicators, and coding for descriptive characteristics and administrator attitudes towards inclusion tasks based on independent work carried out by two researchers. The secondary researcher coded all articles in the screening, descriptive coding, and application of quality indicators phases and 20% of the articles for coding findings regarding administrator attitudes. The initial ratings formed the basis for calculating the IRR, with any disagreements being resolved through mediation. The IRR coefficients achieved were 100% for screening, 99% for descriptive coding (range 91–100%), 96% for coding findings on administrator attitudes (range 92–98%), and 98% for the application of quality indicators (range 91–100%).

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Features of the Included Studies

3.1.1. Author/Country, Publication Type, and Methodology

The studies were conducted in six different countries by eighteen different groups of researchers. The majority of studies originated from the USA (61%), followed by Türkiye (11%), Australia (6%), Saudi Arabia (6%), China (6%), Hong Kong (6%), and Israel (6%). Twelve were research articles (67%), and six were doctoral dissertations (33%). The research methods were primarily qualitative (67%), with phenomenology, case studies, and action research being common. Quantitative (28%) and mixed methods (6%) were also represented.

3.1.2. Participant Characteristics

Age/Gender/Ethnicity. Age details were reported in only 22% of the studies, with participant ages ranging from 27 to 60 years. Gender information was available in 61% of the studies, documenting 402 females and 141 males; however, gender was not reported for 202 participants in seven studies. Ethnicity was specified in only 33% of the studies, identifying the participants as Turkish, Arab, White, Black, Latino, and Chinese.

Job Title/Year of Experience. The studies involved 735 participants, including principals (50%), administrators (22%), directors (17%), and school leaders (6%). Data from both principals and assistant principals were included in one study (Rakap, 2024). About 56% of the studies reported on the duration of experience, with years of experience among administrators ranging from 1 to 31 years.

3.1.3. Student Disability Types

In 94% of the studies, specific types of disabilities among children in inclusive education programs were not detailed. One exception was Brotherson et al. (2001), which noted the inclusion of students considered at risk.

3.1.4. Setting

Thirty-nine percent of the studies were conducted with administrators in preschool settings. The other studies focused on administrators in primary schools (22%), K-12 schools (11%), and laboratory schools with preschool classrooms (6%). Additionally, two studies targeted childcare center administrators.

3.1.5. Data Collection Tool/Measure

Most qualitative studies (n = 11) primarily used interviews for data collection. One dissertation study (Jordan, 2015) expanded the methods to include interviews, observations, field notes, and document analysis. Half of these studies (50%) provided their interview questions and explained their development process. The quantitative studies employed various surveys, including the Principals’ Attitudes Towards Inclusive Education (Bailey, 2004) Scale, the Multidimensional Attitudes toward Inclusive Education Scale (Mahat, 2008), and the Principals and Inclusion Survey (Ball & Green, 2014). Two studies did not specify the surveys used. The sole mixed-methods study combined the Autism Inclusion Questionnaire (Segall, 2011) for quantitative data with interviews for qualitative insights.

3.1.6. Data Analysis Strategy

Content analysis was the primary method in the majority of qualitative studies (n = 7). Individual studies applied specific techniques, such as constant comparison analysis (Brotherson et al., 2001) and open coding analysis (Alexander, 2023). Another study (Steed et al., 2024) combined open coding with constant comparison methods. However, two studies (Hu & Roberts, 2011; Manar & Murad, 2022) did not specify their analysis techniques. The quantitative studies employed a variety of methods, including descriptive analysis (n = 5), Pearson correlation (n = 3), MANOVA (n = 2), and ANOVA (n = 1), with some studies using multiple techniques simultaneously. The mixed-methods study utilized both descriptive analysis and the Kruskal–Wallis test for data analysis.

3.2. Quality of Studies Included in This Review

The studies in this review were evaluated using the MMAT (Hong et al., 2018), with scores ranging from 40% to 100%, and an average methodological quality score of 70%. The qualitative studies averaged a quality score of 73% (range = 40–100%), while the quantitative studies averaged 64% (range = 40–80%). The mixed-methods study scored 60%. The qualitative studies showed limitations in linking data to findings (67% of the studies), interpreting results robustly (25% of the studies), and maintaining coherence in data collection, analysis, and interpretation (58% of the studies). The quantitative studies often faced a significant risk of nonresponse bias (80%) and had issues with the relevance of sampling strategies (40%) and sample representativeness (60%). The mixed-methods study struggled with effectively integrating and interpreting qualitative and quantitative elements, showing inconsistencies between the two strands.

3.3. Administrator Attitudes Towards Inclusion

3.3.1. Qualitative Findings

Qualitative data from included studies revealed eight key themes on early childhood administrators’ attitudes towards inclusion: positive attitudes, role perception, challenges, factors influencing attitudes, training needs, severity of disabilities considerations, relationship with teacher perceptions, and advocacy for increased awareness (see Table 2 for themes, theme definitions, associated codes and examples).

Table 2.

Themes, theme descriptions, associated codes, and examples.

Positive Attitudes Towards Inclusion. Early childhood administrators consistently expressed positive attitudes towards inclusion, recognizing its significance in promoting diversity and fostering an inclusive learning environment. This sentiment was echoed across multiple studies, with the participants affirming the importance of implementing inclusive education practices at an early age (Alqadhi, 2019). Principals and directors alike emphasized the value of inclusion for children with disabilities and highlighted the societal shift towards greater acceptance and support for inclusive education (Hu & Roberts, 2011; Steed et al., 2024). Their positive attitudes reflected a commitment to creating equitable opportunities for all children within early childhood settings.

Role Perception and Influence. Administrators demonstrated variability in their perception of their role within inclusive education frameworks. Some administrators viewed themselves as influencers, actively shaping instructional and structural resources for inclusive classrooms (Alexander, 2023). However, others acknowledged their role in supporting teachers within inclusive settings, emphasizing personalized decision-making norms (Yazicioglu, 2021). This diversity in role perception underscores the complexity of leadership within inclusive education contexts and highlights the importance of collaboration and flexibility in meeting the diverse needs of children.

Challenges and Complexities. Early childhood administrators encountered multifaceted challenges and complexities in implementing inclusive practices. Issues such as limited resources, geographic disparities, and individual background knowledge presented barriers to effective inclusive education (Brotherson et al., 2001; Graham & Spandagou, 2011; Yazicioglu, 2021). These challenges underlined the need for tailored support and resources to address the diverse needs of children within inclusive settings. Additionally, administrators must navigate community dynamics and individualized needs to create inclusive environments that support all learners.

Factors Influencing Attitudes. Administrators’ attitudes towards inclusion were influenced by a range of factors, including their conceptualization of inclusion, characteristics of the school community, and attitudes of staff. The success of inclusive practices within schools was significantly affected by administrators’ perceptions of inclusion and their ability to engineer inclusive practices within their school community (Graham & Spandagou, 2011). These factors highlight the importance of comprehensive professional development and collaborative leadership approaches in fostering inclusive school cultures.

Need for Training and Support: Early childhood administrators emphasized the need for comprehensive training and support in inclusive practices. This included enhancing understanding of various disabilities, promoting parental partnership, addressing infrastructure issues, and improving teachers’ knowledge and skills (Manar & Murad, 2022; Yazicioglu, 2021). Administrators stressed the importance of ongoing professional development to effectively implement inclusive education practices, recognizing the critical role of continuous learning in creating inclusive environments.

Consideration of Severity of Disabilities. Some administrators expressed reservations regarding the severity of disabilities and the level of support needed for full inclusion. Concerns about the degree of medical or therapeutic support required for children with disabilities may impact administrators’ perspectives on inclusive practices (Steed et al., 2024). These considerations highlight the need for individualized approaches to inclusion that address the unique needs of each child, while also advocating for sufficient support and resources to promote their success.

Relationship with Teacher Perception. There was a notable relationship between administrators’ positive attitudes towards inclusion and teachers’ perceptions. Administrators who held positive attitudes towards inclusion were more likely to foster inclusive environments within their schools, influencing teachers’ perceptions and practices (Smith & Larwin, 2021). This alignment emphasizes the importance of shared vision and collaborative leadership in promoting inclusive practices that support all members of the school community.

Call for Increased Awareness and Advocacy. Administrators advocated for increased awareness among parents and society regarding the benefits of inclusive education. They emphasized the importance of advocating for improved support and resources to facilitate the successful implementation of inclusive practices (Yazicioglu, 2021). This call for advocacy underscores the collaborative effort needed to promote inclusive education at both the institutional and societal levels. By raising awareness and advocating for inclusive practices, administrators play a crucial role in fostering inclusive school cultures that promote diversity and equity.

3.3.2. Quantitative Findings

The quantitative findings indicate a generally positive perception of inclusion among educational administrators, though challenges and the need for enhanced professional development are also prominent. Amsbary et al. (2023) found that most directors recognize the importance of inclusion but face significant barriers like inadequate training and resources. D’Agostino and Douglas (2021) noted positive attitudes towards including children with autism spectrum disorder, though there was variability in the perceived need for special settings. F. L. M. Lee et al. (2015) observed that experiences with inclusion can positively influence attitudes, which may vary depending on disability type and educational setting. Rakap (2024) highlighted that factors such as gender, educational background, and urban versus rural settings affect attitudes, with more experienced and educated administrators showing greater support. Smith and Larwin (2021) pointed out that principals generally have more positive perceptions of inclusion than teachers, suggesting a potential influence of broader oversight and administrative roles on these perceptions. Additionally, White et al. (2021) identified a significant training and experience gap among principals regarding inclusive practices, emphasizing the importance of addressing these gaps to foster supportive environments for inclusion.

4. Discussion

This systematic review synthesizes early childhood administrators’ attitudes towards inclusion and explores influencing factors. Administrators generally hold positive attitudes but face challenges, such as limited resources, insufficient training, and diverse backgrounds, which affect their ability to implement inclusive practices effectively. Attitudes vary with factors like gender, educational level, administrative role, school location, and experience, highlighting the need for personalized understanding of these perspectives. Below, we discuss the key findings in relation to the existing literature. Limitations and recommendations for future research are presented.

The majority of the studies were based in the United States, highlighting its commitment to inclusive practices in early childhood education. This focus reflects a well-established tradition of promoting educational equity and accessibility (D’Agostino & Douglas, 2021; Steed et al., 2024). The influence of U.S. policies is significant, shaping not only domestic approaches but also serving as a model globally (Guralnick & Bruder, 2016). Studies from other countries, such as Türkiye and Australia, though fewer, provide critical insights that suggest how cultural and educational settings influence attitudes towards inclusion, highlighting the need for more focused research in diverse contexts (Rakap, 2024).

The extensive use of qualitative research methods across the reviewed studies reflects a concerted effort to delve deeply into early childhood administrators’ nuanced perspectives on inclusion, exploring the intricacies of their attitudes, which are shaped by personal beliefs, values, and experiences. While these methods provide a valuable in-depth understanding, they are constrained by their inability to engage large participant groups because of their intensive nature (Leko et al., 2021). In contrast, quantitative methods, though less frequently employed, reach larger groups and provide a broader view of attitudes towards inclusion, albeit sometimes at the expense of depth (Rahman, 2017). The use of mixed methods in one study integrates the strengths of both qualitative and quantitative research to offer a comprehensive understanding of administrators’ attitudes by synthesizing the insights of qualitative data with the coverage of quantitative analysis (Corr et al., 2020). This approach may provide nuanced insights into the complex dynamics of inclusion in early childhood education settings.

Participant characteristics, such as age, gender, ethnicity, teaching experience, and special education training, are crucial yet often underreported in the studies reviewed, aligning with broader research findings on the scarcity of such data (Billingsley & Bettini, 2019). These characteristics influence administrators’ attitudes towards inclusion and their ability to implement effective practices (Balikci & Bayrakdar, 2024; F. L. M. Lee et al., 2015; Rakap, 2024; White et al., 2021). For example, more experienced administrators might better understand the nuances of inclusion and the complexities involved, whereas training in special education greatly enhances their competence in addressing diverse learning needs (Amsbary et al., 2023). Furthermore, the type of disabilities in children—mild, moderate, or severe—can also impact administrators’ perceptions and approaches, with only one study addressing this aspect, highlighting the need for detailed reporting to understand the varied challenges in fostering inclusive environments (Balikci, 2025; Steed et al., 2024).

The data collection methods in the reviewed studies reveal areas of concern that could potentially impact the validity and reliability of the research findings. In many cases, there was insufficient disclosure about how interview questions were developed or details about the questionnaires and surveys used, which raises questions about the accuracy and reproducibility of the data (Protogerou & Hagger, 2020). This lack of detailed documentation is problematic as it limits readers’ ability to assess the appropriateness of the tools used, particularly when instruments are adapted to different cultural or educational contexts without thorough validation, potentially leading to biased and inaccurate results (Mohler et al., 2011; Gjersing et al., 2010). Properly reporting the development and adaptation processes of data collection tools is essential for ensuring research integrity and relevance across diverse settings.

The quality assessment of the studies in this review showed varying levels of methodological rigor, highlighting the need for greater methodological quality in future research. The qualitative studies often lacked transparency in documenting interview questions and data recording processes, affecting their reliability and credibility. The quantitative studies commonly did not define variables clearly or report participant characteristics sufficiently, both essential for establishing valid causal relationships and ensuring findings’ generalizability. Additionally, the sole mixed-methods study encountered difficulties in integrating qualitative and quantitative results. Non-experimental quantitative studies, including correlational and descriptive designs, are vital for elucidating the relationships between variables and for describing phenomena within the context of special education (Cook & Cook, 2016). Nonetheless, these studies sometimes lack rigorous methodological scrutiny, which can undermine the validity and reliability of their findings. On the other hand, qualitative studies provide deep insights into the lived experiences, perspectives, and attitudes of early childhood administrators towards inclusion, yet the variability in their methodological quality can significantly affect the trustworthiness and rigor of their conclusions. Clear and transparent reporting of methods, robust data collection procedures, and thoughtful integration of qualitative and quantitative approaches are essential for advancing knowledge (Guetterman & Fetters, 2018).

In synthesizing the qualitative and quantitative findings, a multifaceted understanding of early childhood administrators’ attitudes towards inclusion emerges. The qualitative results reveal a predominantly positive attitude towards inclusion, highlighting its importance in promoting diversity and creating inclusive educational environments (Steed et al., 2024). Despite these positive attitudes, administrators also report significant challenges in implementing inclusive education, such as limited resources, insufficient training, and the influence of their background knowledge, which pose practical obstacles to effective inclusion (Brotherson et al., 2001; Graham & Spandagou, 2011; Yazicioglu, 2021). Moreover, the qualitative findings reveal a diversity in how administrators perceive their roles, suggesting the need for tailored approaches to address their specific challenges and responsibilities in fostering inclusive practices (Alexander, 2023). Additionally, factors such as the administrators’ conceptualization of inclusion, the characteristics of the school community, and the attitudes of staff are shown to significantly influence their perspectives (Graham & Spandagou, 2011). The studies also emphasize the crucial role of comprehensive training and ongoing professional development in equipping administrators to meet the diverse needs within inclusive settings effectively (Manar & Murad, 2022; Yazicioglu, 2021).

Complementing these qualitative insights, the quantitative data generally reflect a positive disposition towards inclusion among administrators, albeit with noted variations in readiness and specific challenges that align with different demographic and experiential factors, such as gender, education level, role, and location (Amsbary et al., 2023; Rakap, 2024). These quantitative findings underline the complex and layered nature of administrators’ attitudes towards inclusion and reinforce the importance of considering both individual and contextual factors in comprehensively understanding these attitudes.

4.1. Limitations

While this systematic review offers insights into early childhood administrators’ attitudes towards inclusion, it is important to recognize several limitations that could impact the interpretation of the findings. First, this review was restricted to studies published in English, potentially omitting pertinent research conducted in other languages. This limitation may skew the understanding of global perspectives on administrators’ attitudes towards inclusion, as non-English studies could offer additional insights from different cultural and educational contexts. Second, the scope of this review was confined to peer-reviewed journals and theses/dissertations, which might exclude valuable data from unpublished studies or the grey literature that could provide a more comprehensive view of the topic. Third, although the search did not limit studies by publication date, the dependence on specific databases and predefined search terms might have led to the exclusion of older or less accessible studies not indexed in the selected databases. Additionally, while the search terms were designed to align with this review’s focus on disability-related inclusion, it is possible that relevant studies using alternative terms such as “special educational needs” or “anti-bias” were unintentionally excluded. These terms are often associated with different educational frameworks or focal points (e.g., K–12 systems, curriculum strategies) and may not have captured administrator-specific perspectives on disability inclusion in early childhood settings. Finally, the methodological challenges identified in the reviewed studies, such as insufficient transparency in data collection methods and variable methodological rigor across different study designs, might have influenced the reliability and validity of the findings presented.

4.2. Recommendation for Future Research

Addressing the limitations in the current research on early childhood administrators’ attitudes towards inclusion is crucial for enhancing our understanding and improving educational systems. A significant limitation is the predominant focus on studies from the United States, limiting the diversity of perspectives and the generalizability of findings. Future research should expand to include perspectives from countries that are actively developing inclusive policies. Another major concern is the varied methodological rigor across the studies, especially issues related to data collection and analysis transparency. Future studies should adhere to rigorous methodologies and transparent reporting to enhance reliability and validity. This includes detailed descriptions of data collection processes and consistent application of rigorous analysis techniques.

Additionally, employing mixed methods could provide a more comprehensive understanding of attitudes towards inclusion by combining qualitative depth with quantitative breadth. It is also essential to report comprehensive participant characteristics, like age, gender, ethnicity, experience, and training, to understand how these factors influence attitudes towards inclusion. Finally, researchers should ensure that the development and selection of interview questions and surveys are transparent and detailed, facilitating study replicability and reliability verification. The use of culturally appropriate research tools, especially in diverse cultural contexts, is critical. This approach will ensure that the data collected are both accurate and relevant, helping to broaden our understanding of early childhood administrators’ attitudes and support the development of effective inclusive education practices globally.

4.3. Implications for Policy and Practice

The findings from this systematic review on early childhood administrators’ attitudes towards inclusion have important implications for both policy and practice to enhance inclusive education. Administrators generally show a positive disposition towards inclusion but face significant challenges, like resource constraints and insufficient training, which highlight areas requiring immediate attention. To foster effective inclusion, there is a need for enhanced resource allocation, with policies directing more funding to early childhood education for resources and support services. Comprehensive training programs should be mandated, ensuring that administrators are well-versed in inclusive practices and legal frameworks. On the practical side, institutions should focus on providing ongoing training to administrators, emphasizing skills to manage diverse classrooms and engage with the community effectively. Clarifying the roles of administrators in promoting inclusion within their schools will empower them to implement necessary changes confidently. Additionally, fostering cultural competence among all educational staff will aid in addressing the varied needs of students, making education more accessible. Schools should also develop robust evaluation and feedback mechanisms to continuously refine and improve inclusion strategies based on real-world feedback and outcomes. By addressing these policy and practice implications, educational leaders will be better equipped to lead and sustain inclusive educational environments, which ultimately lead to more equitable educational outcomes for all children.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this systematic review has synthesized the existing literature to explore early childhood administrators’ attitudes towards inclusive education. Although positive attitudes prevail, notable challenges, such as inadequate training and resource constraints, impact the effective implementation of inclusive practices. These findings stress the importance of continuous professional development and robust support systems to assist administrators in successfully advocating for and maintaining inclusive environments.

Moreover, this review indicates a need for more diversified studies that extend into various cultural and educational contexts, enriching our understanding of global practices and challenges in inclusive education. It also calls for improvements in research methodologies, particularly advocating for the adoption of mixed-methods approaches that merge quantitative rigor with qualitative insights. By addressing these research gaps, future studies can enhance our comprehension of how early childhood administrators’ attitudes influence the landscape of inclusive education, leading to more effective policies and practices that uphold the principles of equity and inclusion.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.B.; Methodology, S.B.; Formal analysis, S.B.; Investigation, S.B.; Data curation, S.B.; Validation, E.G.; Quality assessment, S.B., E.G. and S.R.; Writing—original draft, S.B.; Writing-review & editing, S.B., E.G. and S.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- Ainscow, M., & Miles, S. (2008). Making education for all inclusive: Where next? Prospects, 38(1), 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, D. (2023). Principals’ perceptions of quality inclusion in Pre-K programs [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Walden University.

- Alqadhi, R. (2019). Moving forward toward implementing inclusion in early childhood education in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia: Exploring parents’, teachers’ and administrators’ knowledge and perception [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Washington State University.

- Alquraini, T. A. (2011). Teachers’ perspectives of inclusion of the students with severe disabilities in elementary schools in Saudi Arabia [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Ohio University.

- Amsbary, J., Yang, H. W., Sam, A., Lim, C. I., & Vinh, M. (2023). Practitioner and director perceptions, beliefs, and practices related to STEM and inclusion in early childhood. Early Childhood Education Journal, 52(2024), 705–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avramidis, E., & Norwich, B. (2002). Teachers’ attitudes towards integration/inclusion: A review of the literature. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 17(2), 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, J. (2004). The validation of a scale to measure school principals’ attitudes toward the inclusion of students with disabilities in regular schools. Australian Psychologist, 39(1), 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balikci, S. (2025). Attitudes and perspectives of early childcare center directors toward inclusion of young children with disabilities [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of North Carolina Greensboro.

- Balikci, S., & Bayrakdar, U. (2024). How do early childhood leaders perceive inclusion of young children with disabilities in general education classrooms? Turkish Journal of Special Education Research and Practice, 6(2), 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, K., & Green, R. L. (2014). An investigation of the attitudes of school leaders toward the inclusion of students with disabilities in the general education setting. National Forum of Applied Educational Research Journal, 27(1/2), 57–76. [Google Scholar]

- Billingsley, B., & Bettini, E. (2019). Special education teacher attrition and retention: A review of the literature. Review of Educational Research, 89(5), 697–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black-Hawkins, K., Florian, L., & Rouse, M. (2007). Achievement and inclusion in schools. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Brotherson, M. J., Sheriff, G., Milburn, P., & Schertz, M. (2001). Elementary school principals and their needs and issues for inclusive early childhood programs. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 21(1), 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buell, M. J., Hallam, R., Gamel-McCormick, M., & Scheer, S. B. (1999). A survey of general and special education teachers’ perceptions and inservice needs concerning inclusion. International Journal of Disability, Development & Education, 46(2), 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, B. G., & Cook, L. (2016). Research designs and special education research: Different designs address different questions. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 31(4), 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corr, C., Snodgrass, M. R., Greene, J. C., Meadan, H., & Santos, R. M. (2020). Mixed methods in early childhood special education research: Purposes, challenges, and guidance. Journal of Early Intervention, 42(1), 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agostino, S. R., & Douglas, S. N. (2021). Early childhood educators’ perceptions of inclusion for children with autism spectrum disorder. Early Childhood Education Journal, 49, 725–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer, A., Pijl, S. J., & Minnaert, A. (2010). Attitudes of parents towards inclusive education: A review of the literature. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 25(2), 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer, A., Pijl, S. J., & Minnaert, A. (2012). Students’ attitudes towards peers with disabilities: A review of the literature. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 59(4), 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DEC/NAEYC. (2009). Early childhood inclusion: A joint position statement of the Division for Early Childhood (DEC) and the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC). The University of North Carolina, FPG Child Development Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, D. L. (2008). International trends in inclusive education: The continuing challenge to teach one and everyone. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 23(2), 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florian, L. (2012). Preparing teachers to work in inclusive classrooms: Key lessons for the professional development of teacher educators from Scotland’s inclusive development. Journal of Teacher Education, 63(4), 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florian, L., & Black-Hawkins, K. (2011). Exploring inclusive pedagogy. British Educational Research Journal, 37(5), 813–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freer, J. R. (2023). Students’ attitudes toward disability: A systematic literature review (2012–2019). International Journal of Inclusive Education, 27(5), 652–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjersing, L., Caplehorn, J. R., & Clausen, T. (2010). Cross-cultural adaptation of research instruments: Language, setting, time and statistical considerations. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasman, L. R., & Albarracín, D. (2006). Forming attitudes that predict future behavior: A meta-analysis of the attitude-behavior relation. Psychological Bulletin, 132(5), 778–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, L. J., & Spandagou, I. (2011). From vision to reality: Views of primary school principals on inclusive education in New South Wales, Australia. Disability & Society, 26(2), 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guetterman, T. C., & Fetters, M. D. (2018). Two methodological approaches to the integration of mixed methods and case study designs: A systematic review. American Behavioral Scientist, 62(7), 900–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guralnick, M. J., & Bruder, M. B. (2016). Early childhood inclusion in the United States: Goals, current status, and future directions. Infants & Young Children, 29(3), 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q. N., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M.-P., Griffiths, F., Nicolau, B., O’Cathain, A., Rousseau, M.-C., Vedel, I., & Pluye, P. (2018). The mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Education for Information, 34, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B. Y., & Roberts, S. K. (2011). When inclusion is innovation: An examination of administrator perspectives on inclusion in China. Journal of School Leadership, 21(4), 548–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, M. C. (2015). Inclusive leadership in early childhood education: Practices and perspectives of program administrators [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. The University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

- Kraus, S. J. (1995). Attitudes and the prediction of behavior: A meta-analysis of the empirical literature. Personality And Social Psychology Bulletin, 21(1), 58–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lautenbach, F., & Heyder, A. (2019). Changing attitudes to inclusion in preservice teacher education: A systematic review. Educational Research, 61(2), 231–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A. E. (2022). Attitudes, beliefs, and professional behaviors regarding preschool inclusion: A director’s perspective [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Wilkes University.

- Lee, F. L. M., Yeung, A. S., Tracey, D., & Barker, K. (2015). Inclusion of children with special needs in early childhood education: What teacher characteristics matter. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 35(2), 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leko, M. M., Cook, B. G., & Cook, L. (2021). Qualitative methods in special education research. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 36(4), 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loreman, T., Sharma, U., & Forlin, C. (2011). Do preservice teachers feel ready to teach in inclusive classrooms? Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 38(1), 27–44. [Google Scholar]

- Mahat, M. (2008). The development of a psychometrically-sound instrument to measure teachers’ multidimensional attitudes toward inclusive education. International Journal of Special Education, 23(1), 82–92. [Google Scholar]

- Manar, S., & Murad, T. (2022). Integration of children with special needs in regular kindergartens in the Arab sector in Israel, from the perspective of kindergarten teachers and principals. International Journal of Early Childhood Special Education, 14(3), 3449–3462. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, J. A. (2013). Qualitative research design: An interactive approach. SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook. SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Mohler, P., Dorer, B., De Jong, J., & Hu, M. (2011). Guidelines for best practice in cross-cultural surveys. Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Odom, S. L., Buysse, V., & Soukakou, E. (2011). Inclusion for young children with disabilities: A quarter century of research perspectives. Journal of Early Intervention, 33(4), 344–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrosky, M. M., Laumann, B. M., & Hsieh, W. (2006). Early childhood teachers’ beliefs and attitudes about inclusion: What does the research tell us? In B. Spodek, & O. N. Saracho (Eds.), Handbook of research on the education of young children (pp. 411–422). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Pijl, S. J., & Meijer, C. J. W. (1997). Factors in inclusion, a framework. In S. J. Pijl, C. J. W. Meijer, & S. Hegarty (Eds.), Inclusive education: A global agenda (pp. 8–13). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Protogerou, C., & Hagger, M. S. (2020). A checklist to assess the quality of survey studies in psychology. Methods in Psychology, 3(2020), 100031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M. S. (2017). The advantages and disadvantages of using qualitative and quantitative approaches and methods in language “testing and assessment” research: A literature review. Journal of Education and Learning, 6(1), 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakap, S. (2024). Pathways to inclusion: Exploring early childhood school administrators’ attitudes toward including children with disabilities in Türkiye. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 39(3), 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakap, S., & Kaczmarek, L. (2010). Teachers’ attitudes towards inclusion in Turkey. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 25, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravet, J., & Mtika, P. (2024). Educational inclusion in resource-constrained contexts: A study of rural primary schools in Cambodia. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 28(1), 16–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, C. D. (2019). Child care center directors’ perceptions of their efforts to create inclusive environments in a Quality Rating and Improvement System (QRIS) [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Drexel University.

- Russell, A., Scriney, A., & Smyth, S. (2023). Educator attitudes towards the inclusion of students with autism spectrum disorders in mainstream education: A systematic review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 10(3), 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakız, H., Ergün, N., & Göksu, İ. (2023). Developing and validating the Attitudes Towards Inclusive Education Scale (AIES) around contemporary paradigms of inclusion. The Asia-PacificEducation Researcher, 33, 1053–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segall, M. J. (2011). Inclusion of students with autism spectrum disorder: Educator experience, knowledge, and attitudes [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Georgia, Athens.

- Slee, R. (2011). The irregular school: Exclusion, schooling, and inclusive education. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, E., & Larwin, K. H. (2021). Will they be welcomed in? The impact of K-12 teachers’ and principals’ perceptions of inclusion of students with disabilities. Journal of Organizational and Educational Leadership, 6(3), 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Stangor, D. C. (2014). Principles of social psychology (1st ed.). BCcampus. [Google Scholar]

- Starratt, R. J. (2003). Centering educational administration: Cultivating meaning, community, responsibility. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Steed, E. A., Strain, P. S., Rausch, A., Hodges, A., & Bold, E. (2024). Early childhood administrator perspectives about preschool inclusion: A Qualitative interview study. Early Childhood Education Journal, 52(3), 527–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Syring, L. K. (2018). Administrators’ perspectives on inclusion in preschool: A qualitative multiple case study [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Northcentral University.

- Van Steen, T., & Wilson, C. (2020). Individual and cultural factors in teachers’ attitudes towards inclusion: A meta-analysis. Teaching and Teacher Education, 95, 103127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K. M., Hunter, W., Green, R. L., & Mueller, C. E. (2021). Principals’ attitudes toward the inclusion of students with exceptionalities in the general education classroom. Journal of Special Education Leadership, 34(2), 72–81. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, E., & O’Raw, P. (2010). Literature review of the principles and practices relating to inclusive education for children with special educational needs. National Council for Special Education. [Google Scholar]

- Yazicioglu, T. (2021). Views of the school principals about the inclusive education and practices. International Journal of Progressive Education, 17(5), 241–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).