‘We Just Do What the Teacher Says’—Students’ Perspectives on Participation in ‘Inclusive’ Physical Education Classes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Approach

2.2. Sample and Data Collection

- “If you had to describe how you feel in PE with one word, what would you say? Can you explain why you chose the word?”

- “What does it mean for you to “perform” or “achieve something” in PE?”

- How do you feel about the assessment of performance in PE? Would you prefer it to be different? How?”

2.3. Data Analysis

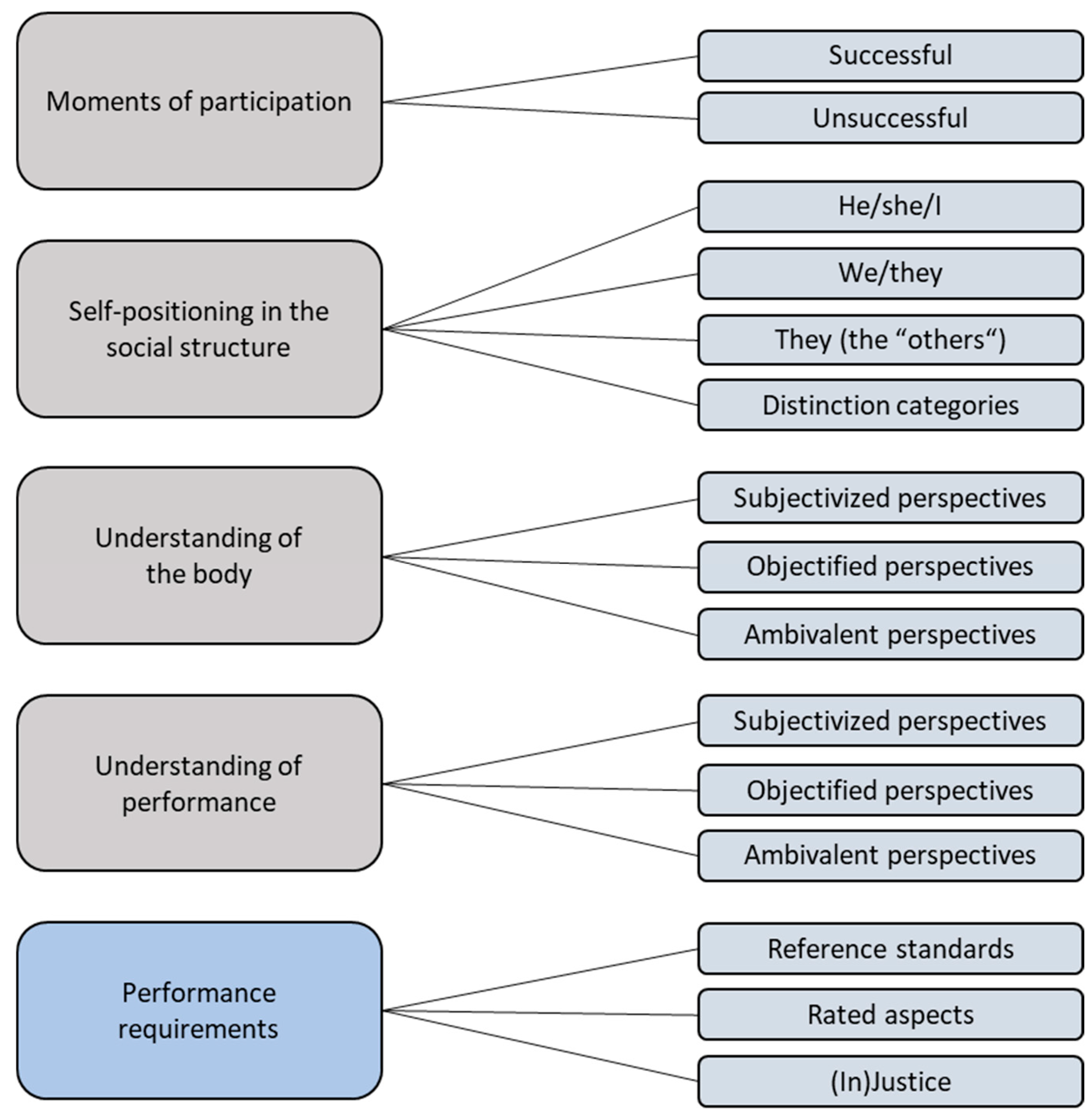

- Moments of participation

- Self-positioning in the social structure

- Conceptualizations of the body

- Understanding of performance

3. Results

3.1. Findings Across the Sample by Categories

3.1.1. Moments of Participation

3.1.2. Self-Positioning

3.1.3. Understanding of the Body

3.1.4. Understanding of Performance

3.1.5. Performance Requirements

3.2. Portraits

3.2.1. Portrait of Anna

3.2.2. Portrait of Felix

3.2.3. Portrait of Marta

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Andersen, M. L., & Hill Collins, P. (Eds.). (2020). Race, class, and gender: Intersections and inequalities (10th ed.). Cengage. [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum, P. M. (2002). Multicultural and diversity education: A reference handbook. ABC-CLIO. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, D., Varea, V., Bergentoft, H., & Schubring, A. (2023). Body image in physical education: A narrative review. Sport, Education and Society, 28(7), 824–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, D., & Große Prues, P. (2025). Demokratiebildung als querschnittsaufgabe: Fachdidaktische zugänge, perspektiven und potenziale (1st ed.). Wochenschau Verlag Dr. Kurt Debus GmbH. [Google Scholar]

- Bartsch, F., Wagner, I., & Rulofs, B. (2021). Students from refugee backgrounds in physical education: A survey of teachers’ perceptions. European Physical Education Review, 27(4), 854–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrán-Carrillo, V. J., Devís-Devís, J., & Peiró-Velert, C. (2018). The influence of body discourses on adolescents’ (non)participation in physical activity. Sport, Education and Society, 23(3), 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesta, G. J. J. (2022). World-centred education: A view for the present. Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Brink, C., & Block, M. (2024). Navigating middle school physical education with a physical disability: Personal experiences and challenges. European Journal of Adapted Physical Activity, 17, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhlke, N. (2020). Psychosoziale normalitätsanforderungen im schulsport. Exemplarische ableitungen aus erkenntnissen zu Sichtweisen jugendlicher mit einer zugeschriebenen psychischen Störung. Leipziger Sportwissenschaftliche Beiträge, 61(1), 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, F., & Magnusson, J. (2006). Taking part counts: Adolescents’ experiences of the transition from inactivity to active participation in school-based physical education. Health Education Research, 21(6), 872–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Curran, T., & Standage, M. (2017). Psychological needs and the quality of student engagement in physical education: Teachers as key facilitators. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 36(3), 262–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eikel, A. (2007). Demokratische partizipation in der schule. In A. Eikel, & G. Haan (Eds.), Demokratische partizipation in der schule. Ermöglichen, fördern, umsetzen (pp. 7–41). Wochenschau-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, J., & Penney, D. (2008). Levels on the playing field: The social construction of physical ‘ability’ in the physical education curriculum. Physical Education & Sport Pedagogy, 13(1), 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, H. (2005). Still feeling like a spare piece of luggage? Embodied experiences of (dis)ability in physical education and school sport. Physical Education & Sport Pedagogy, 10(1), 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flick, U. (2018). An introduction to qualitative research (6th ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Gerdin, G. (2025). ‘Level the playing field’—pupils’ experiences of inclusion and social justice in physical education and health. Sport, Education and Society, 30(4), 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giese, M., & Grenier, M. (2025). “…it’s so funny to just throw off the blind girl” subjective experiences of barriers in physical education with visually impaired students—An emancipatory bad practice approach. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 7, 1515458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giese, M., & Hoffmann, T. (2024). Die ausgeschlossenen? “Leistungsgerechtigkeit” im inklusiven sportunterricht: Eine ableismkritische analyse aus behinderten- und inklusionspädagogischer perspektive. German Journal of Exercise and Sport Research, 54(4), 552–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, P. A., Stringfellow, A., Johnson, J. L., Dixon, C. E., Hollett, N., & Ward, K. (2022). Examining the concept of engagement in physical education. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 27(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollibaugh, C. (2023). Grading strategies in physical education. Strategies, 36(5), 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutzler, Y., Meier, S., Reuker, S., & Zitomer, M. (2019). Attitudes and self-efficacy of physical education teachers toward inclusion of children with disabilities: A narrative review of international literature. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 24(3), 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenssen, A. R. (2018). Inclusion and democratic values in physical education. Association for Teacher Education in Europe, 42, 206–219. [Google Scholar]

- Kreinbucher-Bekerle, C., & Mikosch, J. (2023). Students’ perspectives on school sports trips in the context of participation and democratic education. Children, 10(4), 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreinbucher-Bekerle, C., & Ruin, S. (2025). Entwicklung und erprobung eines fragebogens zu beteiligungsmöglichkeiten von schüler:innen im sportunterricht (BEM-SU-S). German Journal of Exercise and Sport Research, 55, 566–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krijgsman, C., Vansteenkiste, M., Van Tartwijk, J., Maes, J., Borghouts, L., Cardon, G., Mainhard, T., & Haerens, L. (2017). Performance grading and motivational functioning and fear in physical education: A self-determination theory perspective. Learning and Individual Differences, 55, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckartz, U., & Rädiker, S. (2023). Qualitative content analysis: Methods, practice and software (2nd ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Mastagli, M., Van Hoye, A., Hainaut, J.-P., & Bolmont, B. (2022). The role of an empowering motivational climate on pupils’ concentration and distraction in physical education. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 41(2), 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecheril, P. (2008). “Kompetenzlosigkeitskompetenz”. Pädagogisches Handeln unter Einwanderungsbedingungen. In Interkulturelle Kompetenz und pädagogische Professionalität (pp. 15–34). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, S. (2023). Leisten, leistung, leistungsbewertung in einem diversitätssensiblen sportunterricht. In S. Meier (Ed.), Leistung und Diversität im schulsport (pp. 111–130). Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milton, D., Appleton, P. R., Quested, E., Bryant, A., & Duda, J. L. (2025). Examining the mediating role of motivation in the relationships between teacher-created motivational climates and quality of engagement in secondary school physical education. PLoS ONE, 20(1), e0316729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, J., & Böhlke, N. (2023). Physical education from LGBTQ+ students’ perspective. A systematic review of qualitative studies. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 28(6), 601–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patall, E. A. (2024). Agentic engagement: Transcending passive motivation. Motivation Science, 10(3), 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prengel, A. (2019). Pädagogik der Vielfalt: Verschiedenheit und Gleichberechtigung in interkultureller, feministischer und integrativer Pädagogik. Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J., & Shin, S. H. (2020). How teachers can support students’ agentic engagement. Theory Into Practice, 59(2), 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruin, S. (2023). Vielfalt im schulsport—Zum anspruch einer diversitätssensiblen fachdidaktik. In G. Stibbe, & S. Ruin (Eds.), Sportdidaktik und schulsport: Zentrale Themen einer diversitätssensiblen fachdidaktik (pp. 53–77). Hofmann. [Google Scholar]

- Ruin, S., Haegele, J. A., Giese, M., & Baumgärtner, J. (2023). Barriers and challenges for visually impaired students in PE—An interview study with students in Austria, Germany, and the USA. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(22), 7081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruin, S., & Meier, S. (2017). Body and performance in (inclusive) PE settings—An examination of teacher attitudes. International Journal of Physical Education, 54(3), 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rulofs, B. (2014). “Diversität” und “diversitätsmanagement”. Auslegungen der konzepte für die entwicklung von sportorganisa-tionen. In DOSB [Deutscher Olympischer Sportbund] (Ed.), Expertise. “diversität, inklusion, integration und interkulturalität—Leitbegriffe der politik, sportwissenschaftliche diskurse und empfehlung für den DOSB und die dsj” (pp. 7–13). DOSB. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer-Cavaliere, N., & Watkinson, E. J. (2010). Inclusion understood from the perspectives of children with disability. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 27(4), 275–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringfellow, A., Wang, C., Farias, C. F. G., & Hastie, P. A. (2024). The development of an “Engagement in Physical Education” scale. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 6, 1460267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczupał, B. (2017). Incapacitation as a mean of protecting the dignity of the persons with disabilities in the view of convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. Psycho-Educational Research Reviews, 6(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, S. D., & Penney, D. (2021). Setting policy and student agency in physical education: Students as policy actors. Sport, Education and Society, 26(3), 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimlich, M., & Reuter, C. (2024). Perspectives of students with intellectual disabilities on inclusive physical education in Germany. European Journal of Adapted Physical Activity, 17, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Student Names 1 | Age | Grade | School | Interviewer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maria | 13 | 4 | 1 | Emma |

| Marlene | 14 | 4 | 1 | Arthur |

| Markus | 13 | 4 | 1 | Arthur |

| Lisa | 13 | 4 | 1 | Oskar |

| Cornelia | 10 | 1 | 2 | Emma |

| Patrick | 10 | 1 | 2 | Leo |

| Kevin | 10 | 1 | 2 | Leo |

| Melissa | 10 | 1 | 2 | Emma |

| Ken | 11 | 2 | 2 | Emma |

| Liam | 11 | 2 | 2 | Arthur |

| Ismael | 12 | 2 | 2 | Emma |

| Bilal | 12 | 2 | 2 | Emma |

| Sofija | 12 | 2 | 2 | Arthur |

| Markus | 11 | 1 | 2 | Mia |

| Laura | 11 | 1 | 2 | Mia |

| Linda | 10 | 1 | 2 | Mia |

| Samantha | 11 | 1 | 2 | Leo |

| Milan | 10 | 1 | 2 | Leo |

| Stefan | 11 | 2 | 2 | Mia |

| Mario | 12 | 2 | 2 | Mia |

| Ada | 11 | 2 | 2 | Mia |

| Marta | 13 | 2 | 2 | Arthur |

| Felix | 13 | 3 | 2 | Arthur |

| Lucas | 12 | 3 | 2 | Mia |

| Simone | 12 | 2 | 2 | Arthur |

| Lea | 12 | 2 | 2 | Emma |

| Matteo | 11 | 2 | 2 | Emma |

| Carmen | 12 | 2 | 2 | Emma |

| Axel | 14 | 3 | 2 | Mia |

| Elina | 12 | 3 | 2 | Mia |

| Imani | 11 | 1 | 3 | Mia |

| Yusuf | 11 | 1 | 3 | Mia |

| Anna | 11 | 1 | 3 | Oskar |

| Florian | 11 | 1 | 3 | Oskar |

| Miro | 10 | 2 | 3 | Oskar |

| Andreas | 11 | 2 | 3 | Oskar |

| Sandro | 12 | 2 | 3 | Julia |

| Anton | 12 | 2 | 3 | Oskar |

| Taher | 14 | 2 | 3 | Oskar |

| Ben | 12 | 2 | 3 | Oskar |

| Main Category | Subcategory | Anchor Example |

|---|---|---|

| Moments of participation | Successful | “We can also always ask in class if we could play a game like this next time or run or something, we can always say that” (School 2, Matteo, pos 78). |

| Unsuccessful | “Some people in my class don’t like PE lessons that much […]. Sometimes they just sit on the bench on the side and don’t join in, […] if I had to guess, I would say […] that they don’t like PE lessons that much” (School 3, Taher, pos. 36). | |

| Self-positioning in the social structure | He/she/I | “[…] I’m almost one of the best in the class, so if you talk to Florian, he’s also a friend of mine, he’s about as good as I am. It’s simply because I’m the best, so no one dares to say anything […]” (School 3, Yusuf, pos. 97). |

| We/they | “For example, like, most of the boys want us, who are not that sporty, to be more strenuous. The girls would perhaps choose something else […]” (School 3, Anna, pos. 30). | |

| They (the others) | “For example, Yusuf, who is more of a sportsman, he would describe it [PE] as somehow ‘boring’ because he’s a football player and all that” (School 3, Florian, pos 33). | |

| Distinction categories | “[…] I don’t think she’s that sporty and maybe she doesn’t like PE lessons that much” (School 3, Imani, pos. 42). “[…] I’m a bit, let’s say bigger, I’ve got actually a few kilograms more than some others in the class […]” (School 2, Felix, Pos. 30). | |

| Understanding of the body | Subjectivized perspectives | “I mean, I’ve talked to a few others about it and they feel the same way, so they feel, most of them feel like they’re not good enough or something, just because they’re a bit bigger” (School 3, Anna, pos. 38). |

| Objectified perspectives | “Yes, I think it’s good, it’s also healthy for the body to move, because if you just sit around doing nothing all the time, you can easily get ill and various diseases can develop” (School 2, Lea, Pos. 60). | |

| Ambivalent perspectives | “There are sporty girls who really like doing sport and a few who don’t like it that much and don’t like … running so fast, which I don’t think is a bad thing in itself” (School 3, Anna, pos. 34). | |

| Understanding of performance | Subjectivized perspectives | “[…] you should just try to be a bit better than last time” (School 1, Maria, pos. 55). |

| Objectified perspectives | “[…] Performance means that you accomplish something, I would say that you achieve something” (School 2, Kevin, pos. 51). | |

| Ambivalent perspectives | For me, performance is when I accomplish something that I have practiced, something that I always wanted to accomplish. (School 2, Melissa, pos. 48). | |

| Performance requirements | Reference standards | “If we do stretch exercises and you can’t do them, the PE teachers said you have to practice them at home, then you should be able to do them at the end of the school year” (School 2, Martin, pos. 68). |

| Rated aspects | “So I think it makes sense to have an assessment in PE lessons so that you can keep improving and so on. But I also think that it’s hard for some people to work with it and some people can’t sit still when new things are explained and that’s then of course subject of assessment and then of course you get a lower grade if you can’t listen” (School 1, Maria, pos. 65). “I would say by participating and yes and by listening and not doing other things, but doing what the teachers say” (School 2, Kevin, Pos. 59). | |

| (In)-Justice | “[…] I think they are simply graded too hard” (School 3, Anna, pos. 57). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sandbichler, B.; Kreinbucher-Bekerle, C.; Ruin, S. ‘We Just Do What the Teacher Says’—Students’ Perspectives on Participation in ‘Inclusive’ Physical Education Classes. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1700. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121700

Sandbichler B, Kreinbucher-Bekerle C, Ruin S. ‘We Just Do What the Teacher Says’—Students’ Perspectives on Participation in ‘Inclusive’ Physical Education Classes. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1700. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121700

Chicago/Turabian StyleSandbichler, Bianca, Christoph Kreinbucher-Bekerle, and Sebastian Ruin. 2025. "‘We Just Do What the Teacher Says’—Students’ Perspectives on Participation in ‘Inclusive’ Physical Education Classes" Education Sciences 15, no. 12: 1700. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121700

APA StyleSandbichler, B., Kreinbucher-Bekerle, C., & Ruin, S. (2025). ‘We Just Do What the Teacher Says’—Students’ Perspectives on Participation in ‘Inclusive’ Physical Education Classes. Education Sciences, 15(12), 1700. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121700