Student-Created Screencasts: A Constructivist Response to the Challenges of Generative AI in Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Potential of Screencasts as a Pedagogical Tool

1.2. Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT)

- “Performance Expectancy (PE): the degree to which an individual believes that using the system will help them to attain gains in the job” (Venkatesh et al., 2003, p. 447).

- “Effort Expectancy (EE): the degree of ease associated with using the system” (Venkatesh et al., 2003, p. 450).

- “Facilitating Conditions (FC): the degree to which an individual believes that an organizational and technical infrastructure exists to support the use of the system” (Venkatesh et al., 2003, p. 453).

- “Social Influence (SI): the degree to which an individual perceives whether others believe they should use the new system” (Venkatesh et al., 2003, p. 451).

1.3. Future Utility

2. Literature Review

2.1. Connecting Constructivism, Authentic Assessment, and Self-Explanation Through Student-Created Content

2.2. Revisiting Assessment Redesign in the AI Era

2.3. Gaps in Existent Research on Student-Created Screencasts

2.4. The Modified Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT)

2.4.1. Effort Expectancy (EE)

2.4.2. Performance Expectancy (PE)

2.4.3. Future Utility (FU)

2.4.4. Attitude (ATT)

2.4.5. Behavioral Intention (BI)

3. Research Model and Hypotheses

3.1. Research Hypotheses

3.2. Moderators

4. Methodology

4.1. Research Method and Participants

4.2. Research Instrument

5. Results and Discussions

5.1. Measurement Model Assessment

- This measure of reliability takes into account the different outer loadings of the indicator variables

5.2. Structural Model Assessment

5.3. Moderating Effect

5.4. Multi-Group Analysis (MGA)

5.5. Students’ Attitudes (ATT) Towards SCSs

5.6. Practical Implications

6. Conclusions

6.1. Limitations

6.2. Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SCS | Student-Created Screencast/Student-Created Screencasts |

| UTAUT | Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology |

| EE | Effort Expectancy |

| PE | Performance Expectancy |

| FU | Future Utility |

| ATT | Attitude |

| BI | Behavioral Intention |

| MGA | Multi-Group Analysis |

References

- Ab Hamid, M. R., Sami, W., & Sidek, M. M. (2017,Discriminant validity assessment: Use of Fornell & Larcker criterion versus HTMT criterion. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 890(1), 012163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkouk, W. A., & Khlaif, Z. N. (2024). AI-resistant assessments in higher education: Practical insights from faculty training workshops. Frontiers in Education, 9, 1499495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R. P. (2007). The legacy of the technology acceptance model and a proposal for a paradigm shift. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 8(4), 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernacki, M. L., Chavez, M. M., & Uesbeck, P. M. (2020). Predicting achievement and providing support before STEM majors begin to fail. Computers & Education, 158, 103999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindu, M. R., & Manikandan, R. (2020). Can humans take medicines to become immortal? A review of Amish Tripathi’s shiva trilogy. European Journal of Molecular & Clinical Medicine, 7(3), 4894–4897. Available online: https://www.ejmcm.com/archives/volume-7/issue-3/7447 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Buabeng-Andoh, C., & Baah, C. (2020). Pre-service teachers’ intention to use learning management system: An integration of UTAUT and TAM. Interactive Technology and Smart Education, 17(4), 455–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardace, A., Hefferon, K., Levina, A., Linn, M., Salehi, S., & Sato, B. K. (2024). Versatile video assignment improves undergraduates’ learning and confidence. Active Learning in Higher Education. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaka, C. (2023a). Detecting AI content in responses generated by ChatGPT, YouChat, and Chatsonic: The case of five AI content detection tools. Journal of Applied Learning and Teaching, 6(2), 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaka, C. (2023b). Stylised-facts view of fourth industrial revolution technologies impacting digital learning and workplace environments: ChatGPT and critical reflections. Frontiers in Education, 8, 1150499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, M. T. H., De Leeuw, N., Chiu, M.-H., & LaVancher, C. (1994). Eliciting self-explanations improves understanding. Cognitive Science, 18(3), 439–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehouche, N. (2021). Plagiarism in the age of massive Generative Pre-trained Transformers (GPT-3). Ethics in Science and Environmental Politics, 21, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Din Eak, P. N., & Annamalai, N. (2024). Enhancing online learning: A systematic literature review exploring the impact of screencast feedback on student learning outcomes. Asian Association of Open Universities Journal, 19(1), 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, P. K., McDonald, C., & Loch, B. (2015). StatsCasts: Screencasts for complementing lectures in statistics courses. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 46(4), 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, C. P. H., Wedel, K., & Rothlauf, F. (2014, August 7–9). Students’ acceptance of e-learning technologies: Combining the technology acceptance model with the didactic circle. Twentieth Americas Conference on Information Systems, Savannah, GA, USA. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/288103752_Students’_acceptance_of_e-learning_technologies_Combining_the_technology_acceptance_model_with_the_didactic_circle (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Ghilay, Y., & Ghilay, R. (2015). Computer courses in higher-education: Improving learning by screencast technology. i-manager’s Journal on Educational Technology, 11(4), 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). Sage Publications Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Howard, M. C., & Nitzl, C. (2020). Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. Journal of Business Research, 109, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, M., Rasmussen, L. M., & Resnik, D. B. (2023). Using AI to write scholarly publications. Accountability in Research, 31, 715–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, F., Herrmann, A., Meyer, F., Vogel, J., & Vollhardt, K. (2007). Kausalmodellierung mit partial least squares: Eine anwendungsorientierte einführung. Gabler. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M., & Sheridan, L. (2015). Back translation: An emerging sophisticated cyber strategy to subvert advances in ‘digital age’ plagiarism detection and prevention. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 40(5), 712–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawaf, F. (2019). Capturing digital experience: The method of video videography. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 36(2), 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khechine, H., Lakhal, S., Pascot, D., & Bytha, A. (2014). UTAUT model for blended learning: The role of gender and age in the intention to use webinars. Interdisciplinary Journal of E-Learning and Learning Objects, 10(1), 33–52. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1058362 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Khlaif, Z. N. (2024). Rethinking educational assessment in the age of artificial intelligence. In Advances in educational technologies and instructional design book series (pp. 89–115). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killam, L. A., Montgomery, P., Luhanga, F. L., Adamic, S., & Carter, L. M. (2024). Co-creation as authentic assessment to support student learning and readiness for practice: A conceptual framework. Teaching and Learning in Nursing, 19(1), e276–e282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kono, S., & Sato, M. (2023). The potentials of partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) in leisure research. Journal of Leisure Research, 54(3), 309–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, S., & Öz, H. (2021). Using Kahoot to improve reading comprehension of English as a foreign language learner. International Online Journal of Education and Teaching (IOJET), 8(2), 1138–1150. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1294319 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Lombardi, M. M. (2008). Making the grade: The role of assessment in authentic learning. EDUCAUSE Learning Initiative. Available online: https://library.educause.edu/resources/2008/1/making-the-grade-the-role-of-assessment-in-authentic-learning (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Lye, C. Y., & Lim, L. (2024). Generative artificial intelligence in tertiary education: Assessment redesign principles and considerations. Education Sciences, 14(6), 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, M. (2019, October 15). Types of classroom interventions. Available online: https://www.theedadvocate.org/types-of-classroom-interventions/ (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Malkawi, N., Awajan, N. W., Alghazo, K. M., & Harafsheh, H. A. (2023). The effectiveness of using student-created questions for assessing their performance in English grammar/case study of “King Abdullah II schools for excellence”. World Journal of English Language, 13(5), 156–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, Y. J., & Hwang, Y. H. (2016). A study of effects of UTAUT-based factors on acceptance of smart health care services. In Advanced multimedia and ubiquitous engineering: Future information technology volume 2 (pp. 317–324). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, C., & Chikwa, G. (2014). Videos: How effective are they and how do students engage with them? Active Learning in Higher Education, 15(1), 25–37. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1469787413514654 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Mullamphy, D. F., Higgins, P. J., Belward, S. R., & Ward, L. M. (2010). To screencast or not to screencast. The ANZIAM Journal, 51, C446–C460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negahban, A., & Chung, C.-H. (2014). Discovering determinants of users perception of mobile device functionality fit. Computers in Human Behavior, 35, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H., & Nguyen, V. A. (2024). An application of model unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT): A use case for a system of personalized learning based on learning styles. International Journal of Information and Education Technology, 14(11), 1574–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Or, C. (2023). The role of attitude in the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology: A meta-analytic structural equation modelling study. International Journal of Technology in Education and Science, 7(4), 552–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orús, C., Barlés, M. J., Belanche, D., Casaló, L., Fraj, E., & Gurrea, R. (2016). The effects of learner-generated videos for YouTube on learning outcomes and satisfaction. Computers & Education, 95, 254–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osamor, A. (2023). Rethinking online assessment strategies: Authenticity versus AI chatbot intervention. Journal of Applied Learning and Teaching, 6(2), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penn, M., & Brown, M. (2022). Is screencast feedback better than text feedback for student learning in higher education? A systematic review. Ubiquitous Learning: An international Journal, 15(2), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, J., Echeazarra, L., Sanz-Santamaría, S., & Gutiérrez, J. (2014). Student-generated online videos to develop cross-curricular and curricular competencies in Nursing Studies. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 580–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, E. (2007). Incorporating videos in online teaching. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 8(3), 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinder-Grover, T., Green, K. R., & Millunchick, J. M. (2011). The efficacy of screencasts to address the diverse academic needs of students in a large lecture course. Advances in Engineering Education, 2(3), 1–13. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1076056 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Qureshi, F. Z. (2024). Redesigning assessments in business education: Addressing generative AI’s impact on academic integrity. International Journal of Science and Research, 13(10), 1659–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A., & Willson, V. L. (2017). One-sample t-test. In Basic and advanced statistical tests. SensePublishers. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, N. P. W. P., Duong, M. P. T., Li, D., Nguyen, M. H., & Vuong, Q. H. (2024). Rethinking the effects of performance expectancy and effort expectancy on new technology adoption: Evidence from Moroccan nursing students. Teaching and Learning in Nursing, 19(3), e557–e565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shieh, R. S. (2012). The impact of Technology-Enabled Active Learning (TEAL) implementation on student learning and teachers’ teaching in a high school context. Computers & Education, 59(2), 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Walt, L., & Bosch, C. (2025). Co-creating OERs in computer science education to foster intrinsic motivation. Education Sciences, 15(7), 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, B., Macgilchrist, F., & Potter, J. (2023). Re-examining AI, automation and datafication in education. Learning, Media and Technology, 48(1), 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winship, C., & Zhuo, X. (2020). Interpreting t-statistics under publication bias: Rough rules of thumb. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 36(2), 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C., Delante, N. L., & Wang, P. (2017). Using PELA to predict international business students’ English writing performance with contextualised English writing workshops as intervention program. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 14(1), 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B., & Chen, X. (2017). Continuance intention to use MOOCs: Integrating the technology acceptance model (TAM) and task technology fit (TTF) model. Computers in Human Behavior, 67, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yankova, D. (2020). On translated plagiarism in academic discourse. English Studies at NBU, 6(2), 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Creator | Focus | Author(s) | Main Research Task(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Teachers | Supplementary Learning Materials | Morris and Chikwa (2014) | Examined customized screencast as optional additional learning resources. |

| Mullamphy et al. (2010) | Documented mathematics lecturers creating screencasts for student support | ||

| Teachers | Feedback Delivery | Din Eak and Annamalai (2024) | Reviewed screencast feedback in online higher education |

| Penn & Brown (2022) | Conducted a systematic review comparing screencast feedback with text feedback | ||

| Teachers | Lecture Enhancement and Recording | Pinder-Grover et al. (2011) | Documented instructor-developed screencasts posted to supplement lectures |

| Ghilay and Ghilay (2015) | Examined courses fully covered by instructor-produced screencast videos | ||

| Teachers | Specialized Subject Support | Dunn et al. (2015) | Analyzed “StatsCats” with lecturer-provided narration |

| Mullamphy et al. (2010) | Documented mathematics lecturers creating screencasts for student support | ||

| Students | Optional Assessment alternative | Orús et al. (2016) | Allowed students to create videos to explain some marketing concepts to replace a written report. |

| Subject Code | Subject Name | Academic Year | Number of Respondents |

|---|---|---|---|

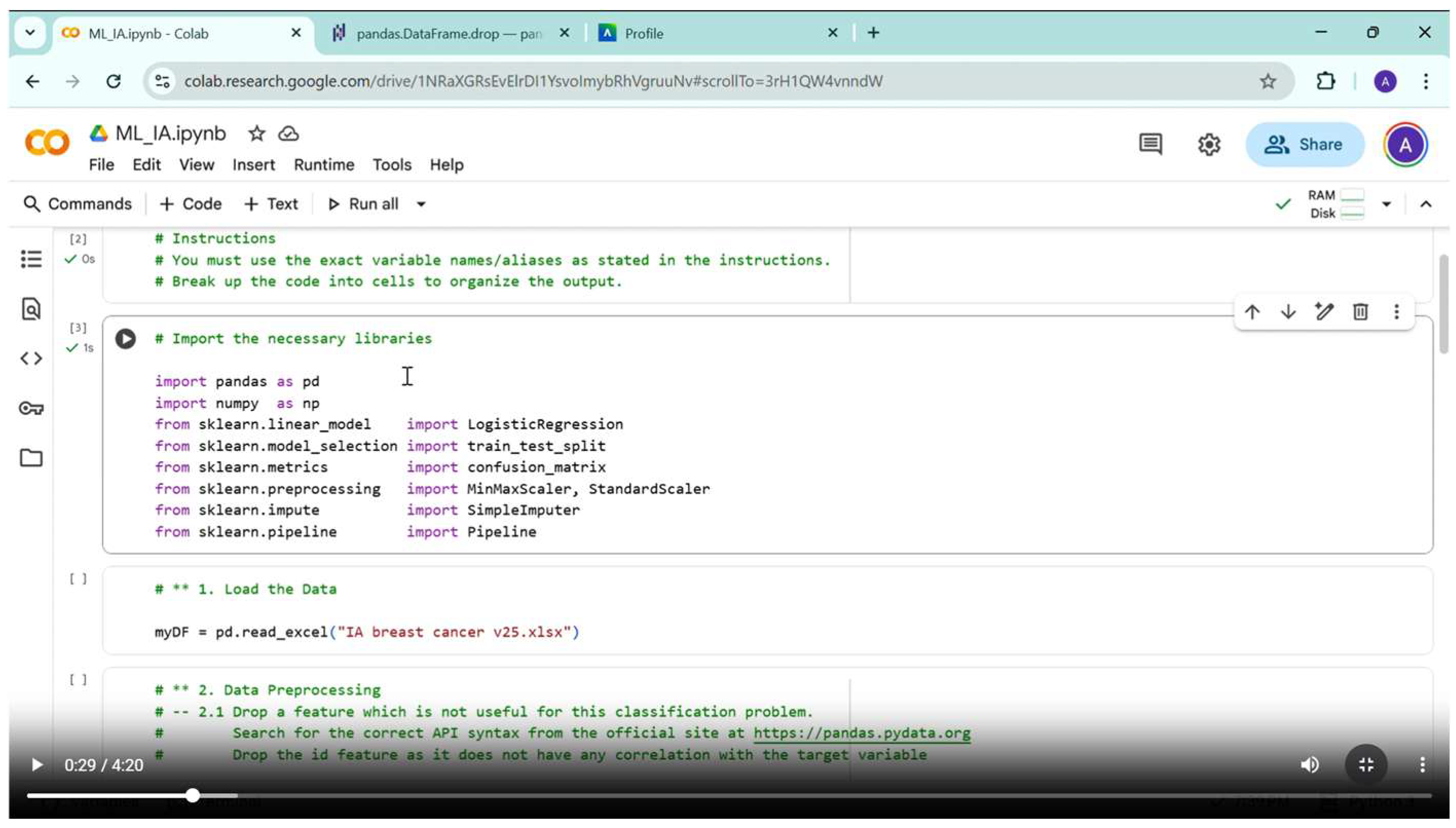

| SEHS4696 | Machine Learning for Data Mining | 24/25 | 49 |

| SEHS2307 | Computer Programming Concepts | 22/23 | 37 |

| SEHH2042 | Computer Programming | 24/25 | 33 |

| SEHS4517 | Web Application Development and Management | 22/23 | 29 |

| SEHS4678 | Artificial Intelligence | 22/23 | 26 |

| LCS3175 | Effective Professional Communication in English | 24/25 | 21 |

| SEHS4678 | Artificial Intelligence | 24/25 | 8 |

| Characteristics | Items | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 165 | 81.28 |

| Female | 38 | 18.72 | |

| Discipline of Study | Science | 162 | 79.80 |

| Non-Science | 40 | 19.70 | |

| Not answered | 1 | ||

| Mode of Study | Full-time | 169 | 83.25 |

| Part-time | 33 | 16.26 | |

| Not answered | 1 | ||

| Year of Study | Junior year | 33 | 16.26 |

| Senior year | 170 | 83.74 |

| Constructs/Questionnaire Items (5-Point Likert Scale) | Source |

|---|---|

| Performance Expectancy (PE) | |

| Creating screencasts improves the quality of my learning activities. | Adapted from Khechine et al. (2014) |

| Creating screencasts makes my learning activities more effective. | |

| If I create screencasts, I will improve the skills I want to learn. | |

| Effort Expectancy (EE) | |

| It will be easy for me to create screencasts. | Adapted from Khechine et al. (2014) |

| The steps to create screencasts are clear to me. | |

| It’ll be easy for me to become skillful at creating screencasts. | |

| Future Utility (FU) | |

| I can use my screencasts to help me revise my learning tasks. | Authors of this research |

| I can use my screencasts to help me demonstrate my work to my colleagues at work. | |

| Attitude (ATT) | |

| I believe that creating screencasts is a good idea in this subject. | Adapted from Wu and Chen (2017) |

| I believe that creating screencasts is good advice in this subject. | |

| I have good impression about screencasts. | |

| Behavioral Intention (BI) | |

| I intend to create screencasts in future. | Adapted from Khechine et al. (2014) |

| I predict I will create screencasts in future. | |

| I plan to create screencasts in future. | |

| Latent Construct | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability (CR) | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Effort Expectancy | 0.891 | 0.932 | 0.820 |

| Performance Expectancy | 0.910 | 0.943 | 0.848 |

| Future Utility | 0.866 | 0.937 | 0.882 |

| Attitude | 0.954 | 0.970 | 0.915 |

| Behavioral intention | 0.964 | 0.977 | 0.933 |

| EE | PE | FU | ATT | BI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EE | 0.906 | ||||

| PE | 0.634 | 0.921 | |||

| FU | 0.582 | 0.760 | 0.939 | ||

| ATT | 0.651 | 0.805 | 0.828 | 0.957 | |

| BI | 0.569 | 0.718 | 0.739 | 0.806 | 0.966 |

| Path | VIF |

|---|---|

| EE → ATT | 1.740 |

| PE → ATT | 2.729 |

| FU → ATT | 2.467 |

| ATT → BI | 1.000 |

| H | Path | Coefficients | t Values | p Values | R2 | f2 | Confirmed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | EE → ATT | 0.157 | 2.755 | 0.006 | 0.773 | 0.062 | Yes |

| H2 | PE → ATT | 0.344 | 5.092 | 0.000 | 0.773 | 0.190 | Yes |

| H3 | FU → ATT | 0.476 | 7.328 | 0.000 | 0.773 | 0.404 | Yes |

| H4 | ATT → BI | 0.806 | 24.563 | 0.000 | 0.650 | 1.859 | Yes |

| H | Path | Coefficient | p Values | Moderating Effect (p < 0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | Gender × EE → ATT | −0.188 | 0.152 | No |

| H2a | Gender × PE → ATT | 0.074 | 0.639 | No |

| H3a | Gender × FU → ATT | 0.018 | 0.895 | No |

| H1b | Year of Study × EE → ATT | −0.103 | 0.020 | Yes |

| H2b | Year of Study × PE → ATT | 0.000 | 0.996 | No |

| H3b | Year of Study × FU → ATT | 0.045 | 0.637 | No |

| H1c | Discipline of Study × EE → ATT | −0.081 | 0.446 | No |

| H2c | Discipline of Study × PE → ATT | −0.033 | 0.835 | No |

| H3c | Discipline of Study × FU → ATT | 0.068 | 0.655 | No |

| H1d | Mode of Study × EE → ATT | 0.093 | 0.454 | No |

| H2d | Mode of Study × PE → ATT | −0.371 | 0.071 | No |

| H3d | Mode of Study × FU → ATT | 0.273 | 0.123 | No |

| Path Coeff. | Path Coeff. | Path Diff. | 1-Tailed p Value | 2-Tailed p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Male | Female | ||||

| EE → ATT | 0.127 | 0.285 | −0.168 | 0.899 | 0.203 |

| PE → ATT | 0.339 | 0.291 | 0.048 | 0.391 | 0.782 |

| FU → ATT | 0.497 | 0.445 | 0.053 | 0.345 | 0.690 |

| ATT → BI | 0.787 | 0.879 | −0.092 | 0.913 | 0.173 |

| Discipline of Study | |||||

| Science | Non-science | ||||

| EE → ATT | 0.135 | 0.210 | −0.075 | 0.768 | 0.464 |

| PE → ATT | 0.342 | 0.427 | −0.085 | 0.747 | 0.506 |

| FU → ATT | 0.485 | 0.463 | 0.022 | 0.442 | 0.884 |

| ATT → BI | 0.828 | 0.780 | 0.048 | 0.270 | 0.539 |

| Mode of Study | |||||

| Full-time | Part-time | ||||

| EE → ATT | 0.159 | 0.077 | 0.082 | 0.264 | 0.528 |

| PE → ATT | 0.314 | 0.642 | −0.327 | 0.967 | 0.065 |

| FU → ATT | 0.504 | 0.244 | 0.260 | 0.065 | 0.130 |

| ATT → BI | 0.826 | 0.764 | 0.063 | 0.282 | 0.564 |

| Year of Study | |||||

| Junior year | Senior year | ||||

| EE → ATT | 0.349 | 0.108 | 0.241 | 0.021 | 0.042 |

| PE → ATT | 0.351 | 0.295 | 0.056 | 0.336 | 0.672 |

| FU → ATT | 0.322 | 0.549 | −0.227 | 0.964 | 0.072 |

| ATT → BI | 0.916 | 0.763 | 0.154 | 0.007 | 0.013 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wong, A.; Tsang, K.; Lin, S.; Chan, L.L. Student-Created Screencasts: A Constructivist Response to the Challenges of Generative AI in Education. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1701. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121701

Wong A, Tsang K, Lin S, Chan LL. Student-Created Screencasts: A Constructivist Response to the Challenges of Generative AI in Education. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1701. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121701

Chicago/Turabian StyleWong, Adam, Ken Tsang, Shuyang Lin, and Lai Lam Chan. 2025. "Student-Created Screencasts: A Constructivist Response to the Challenges of Generative AI in Education" Education Sciences 15, no. 12: 1701. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121701

APA StyleWong, A., Tsang, K., Lin, S., & Chan, L. L. (2025). Student-Created Screencasts: A Constructivist Response to the Challenges of Generative AI in Education. Education Sciences, 15(12), 1701. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121701