From Nearly Unengaged to Transformative: A Typology of Austrian Physical Education Teachers’ Approaches to Social Justice

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Social Justice Pedagogies

1.2. State of Research

1.3. Research Aims

- How do Austrian PE teachers describe their teaching practices in relation to SJPs?

- And what patterns or types of engagement with SJPs emerge from their reported teaching strategies?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

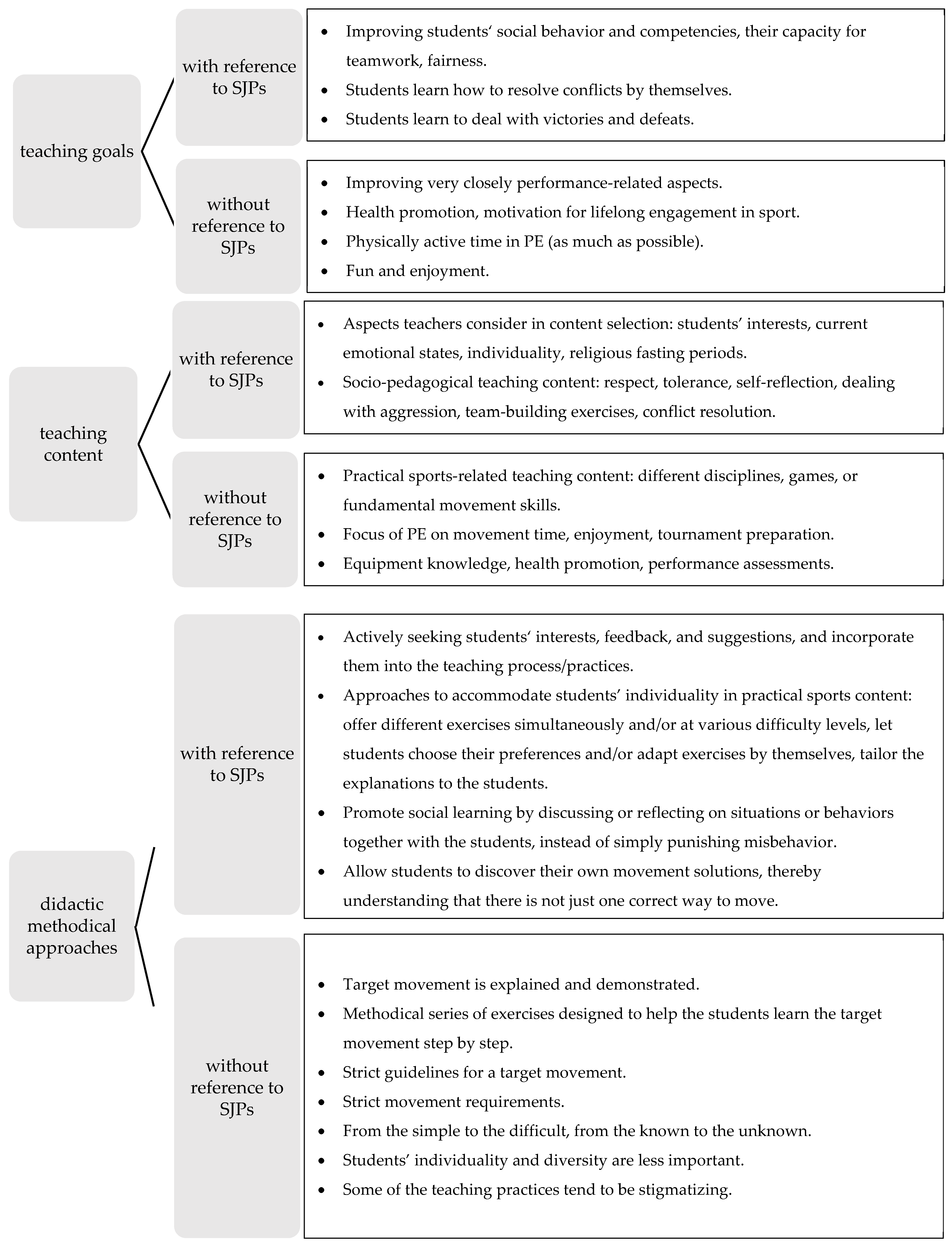

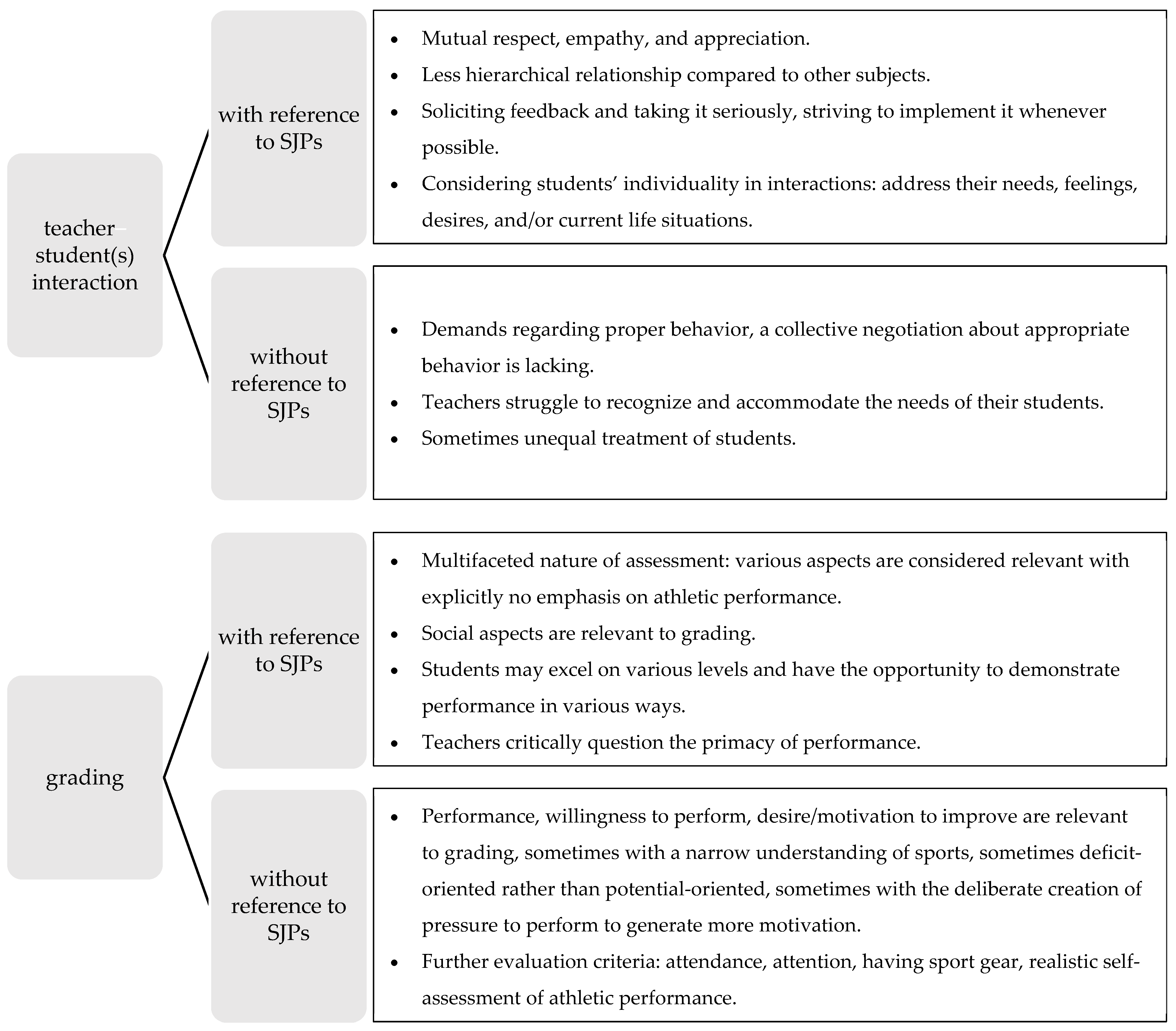

3.1. Teaching Practices with and Without Reference to SJPs

3.2. Results of the Type-Forming Analysis

3.2.1. Maeve—Nearly Unengaged

“I don’t know, social processes are certainly central in PE. I think there is definitely potential for students to engage in social learning. But it really depends on whether I, as a teacher, actively make it a focus—hmm, I’m not sure if I really do that. Maybe sometimes.”(Maeve, pos. 24)

“In planning, [the differences between students] are not really relevant. […] There are always differences—some students are more advanced or have prior experience, while others don’t—and you have to try to address that in class. But in practice, it’s often difficult. Most of the time, I structure exercises from easy to difficult, which means that sometimes it’s less suitable for some and other times less suitable for others. But in the end, everyone still does the same thing because, organizationally, there’s usually no other way.”(Maeve, pos. 20)

“I want to be understanding, and I actually believe that I am. But sometimes I get feedback that I’m not. Well… yeah, self-perception is often quite different from the feedback you receive—that’s actually quite interesting.”(Maeve, pos. 46)

“And it’s also difficult to track individual students’ improvement. I mean, of course, you have a sense of which students are more athletic, and you just assume that they will probably be much better at the beginning than others. But yeah… I actually think it would make more sense to assess individual progress, but measuring that is even more complicated. I would have to test at the beginning and then again at the end, and that would be a lot of effort.”(Maeve, pos. 66)

3.2.2. Maggie—Comprehensive but Contained

“For me, promoting social competence and fair play is extremely important, but in this particular class, it is very difficult to achieve. This includes helping each other, putting away equipment, providing support and assistance, and especially in ball games—where some students are highly competitive—encouraging fair play and social skills. However, as I said, in this group, it is particularly challenging.”(Maggie, pos. 18)

“Yes, student diversity definitely plays a role in my lesson planning. In one weekly PE session, I often try to divide the gym. One half is usually used for games—sometimes different games in each half—while the other half is dedicated to activities like rings, floor gymnastics, or partner acrobatics. By offering these two different options, I aim to better accommodate the students’ varying interests.”(Maggie, pos. 14)

“Everyone starts with the same exercise. Sometimes I specify, ‘You do this, and you do that,’ but most of the time, a natural dynamic develops on its own. Those who have already mastered the exercise tend to start adapting it, for example, by rallying back and forth. Students know they are allowed to modify exercises by themselves to better suit their needs.”(Maggie, pos. 36)

3.2.3. Nick—Transformative Practitioner

“Martial arts are currently very popular among young people. […] Fortunately, I have a lot of experience in this area and am open to incorporating it into my lessons. However, when I do so, I make sure to introduce it gradually. My focus is not solely on competition or the fight itself but also on the proper behavior that comes with it. This means we have a formal greeting at the beginning and a farewell after each match, regardless of the outcome. It is essential that both of these interactions take place with respect.”(Nick, pos. 8)

“Respectful behavior, refereeing, and also self-reflection—thinking about what went well in my role as a referee […] or taking a situation and discussing it with the students: What was right, or what felt right to you, and what was wrong, and why did you feel that way? They quickly realize how to rephrase things, and ‘I-statements’ often come up very naturally without referencing others, because they learn to consider these things from their own perspective. These are the learning processes I try to encourage.”(Nick, pos. 8)

“I completely leave it up to them; they are allowed to go into the equipment room […] and they can take out anything they want. This way, they also learn to handle the equipment and get to know their bodies […] they are free to choose on their own […] There are no restrictions on the types of support because I see no reason to limit their creativity, and they come up with great ideas.”(Nick, pos. 24)

“Dodgeball, the simplest ball game. […] The boys often look down on some girls with a dismissive attitude, thinking, ‘Well, you’re a girl, so it’s okay.‘ In such situations, either I or my colleague frequently join the game to support the girls. […] They need to see my female colleague succeed. Some students have even asked me, ‘Doesn’t it bother you when your colleague beats you?’ I tell them, ‘No, because she throws well. Everyone has their strengths and weaknesses. There are many things she excels at more than I do, and it has nothing to do with gender or physical capability. It’s sometimes about training, sometimes about talent. Just as one of you might be a better thrower, she might excel in mathematics or something else, and will find and enjoy her own talents […].’”(Nick, pos. 14)

“I involve them in decision-making processes and also give them the feeling that they can make a difference, […] that I’ve tried it a hundred thousand times and that it has worked a thousand times, yes, that’s great, but that still doesn’t mean it works for everyone. I’ve had classes where they say, first, that it’s a boring exercise, and second, that it’s a pointless exercise because everyone can do it right away. Well, that’s a statement I can live with, they’re right, it was a bad idea from me, let’s do something else.”(Nick, pos. 22)

“Our grades simply reflect whether someone has performed very well, well, satisfactorily, sufficiently, or not sufficiently. But why can’t someone who isn’t athletic perform their tasks well? I don’t understand that. I often have this discussion with other colleagues.”(Nick, pos. 16)

“And you can tell that this also carries over into school life. They draw a clear distinction between a combative situation and a conflict situation, and they tend to dismiss the latter more easily because they believe it doesn’t belong there. They feel that the important social aspects like respect, tolerance, and those kinds of things are missing.”(Nick, pos. 8)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adams, M. (2022). Roots of social justice pedagogies in social movements. In T. K. Chapman, & N. Hobbel (Eds.), Language, culture and teaching series. Social justice pedagogy across the curriculum: The practice of freedom (2nd ed., pp. 57–83). Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzarito, L., Macdonald, D., Dagkas, S., & Fisette, J. (2017). Revitalizing the physical education social-justice agenda in the global era: Where do we go from here? Quest, 69(2), 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, R. (2006). Physical education and sport in schools: A review of benefits and outcomes. Journal of School Health, 76(8), 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, R., Armour, K., Kirk, D., Jess, M., Pickup, I., Sandford, R., & BERA Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy Special Interest Group. (2009). The educational benefits claimed for physical education and school sport: An academic review. Research Papers in Education, 24(1), 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, L. A. (2016). Theoretical foundations for social justice education. In M. Adams, L. A. Bell, D. J. Goodman, & K. Y. Joshi (Eds.), Teaching for diversity and social justice (pp. 3–26). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Berti, C., Molinari, L., & Speltini, G. (2010). Classroom justice and psychological engagement: Students’ and teachers’ representations. Social Psychology of Education, 13(4), 541–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, G. (2008). Lesson planning (3rd ed.). Continuum International Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

- Dagkas, S. (2016). Problematizing social justice in health pedagogy and youth sport: Intersectionality of race, ethnicity, and class. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 87(3), 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dover, A. G. (2013). Getting “Up to Code”: Preparing for and confronting challenges when teaching for social justice in standards-based classrooms. Action in Teacher Education, 35(2), 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahlenbock, M., & Bindel, T. (2022). Der Wandel der Sportkultur—Von der Jugend in die universitäre Lehramtsausbildung. In A. Böttcher, S. Meier, A. Poweleit, & S. Ruin (Eds.), Schulsport im Spiegel der Zeit(en): Kontinuitäten und Diskontinuitäten im sportdidaktischen Diskurs (pp. 136–150). Meyer & Meyer Sportverlag. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Balboa, J.-M. (2017). A contrasting analysis of the neo-liberal and socio-critical structural strategies in health and physical education: Reflections on the emancipatory agenda within and beyond the limits of HPE. Sport, Education and Society, 22(5), 658–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine-Davis, M., & Faas, D. (2014). Equality and diversity in the classroom: A comparison of students’ and teachers’ attitudes in six European countries. Social Indicators Research, 119(3), 1319–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, K. (2019). What happened to critical pedagogy in physical education? An analysis of key critical work in the field. European Physical Education Review, 25(4), 1128–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, K., & Russell, D. (2015). On being critical in health and physical education. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 20(2), 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García López, L. M., & Kirk, D. (2022). Coaches’ perceptions of sport education: A response to precarity through a pedagogy of affect. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 27(4), 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerdin, G., Larsson, L., Schenker, K., Linnér, S., Mordal Moen, K., Westlie, K., Smith, W., & Philpot, R. (2020). Social justice pedagogies in school health and physical education-building relationships, teaching for social cohesion and addressing social inequities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(18), 6904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerdin, G., Philpot, R., Smith, W., Schenker, K., Mordal Moen, K., Larsson, L., Linnér, S., & Westlie, K. (2021). Teaching for student and societal wellbeing in HPE: Nine pedagogies for social justice. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 3, 702922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerdin, G., Schenker, K., & Linnér, S. (2024). Understandings and enactments of social justice pedagogies in Swedish physical education and health practice. European Physical Education Review, 1356336X241285619, Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerdin, G., Smith, W., Philpot, R., Schenker, K., Moen, K. M., Linnér, S., Westlie, K., & Larsson, L. (2022). Social justice pedagogies in health and physical education. Routledge studies in physical education and youth sport. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, M., Grant, C. A., & Mancheno, V. (2022). These are still revolutionary times: Human rights, social movements, and social justice education. In T. K. Chapman, & N. Hobbel (Eds.), Language, culture and teaching series. Social justice pedagogy across the curriculum: The practice of freedom (2nd ed., pp. 9–31). Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Heidrich, F., & Meier, S. (2025). Exploring social justice pedagogies in physical education in Austria: Teaching practices for diversity and equity. European Physical Education Review, 1356336X251327828, Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, D. (2020). Precarity, critical pedagogy and physical education. Routledge studies in physical education and youth sport. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Klinge, A. (2007). Entscheidungen am Körper: Zur Grundlegung von Kompetenzen in der Sportlehrerausbildung. In W.-D. Miethling, & P. Gieß-Stüber (Eds.), Beruf: Sportlehrer/in: Über Persönlichkeit, Kompetenzen und professionelles Selbst von Sport- und Bewegungslehrern (pp. 25–38). Schneider. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, M. (2019). Austria: Physical education and teacher education in austria. In A. MacPhail, D. Tannehill, & Z. Avsar (Eds.), European physical education teacher education practices (pp. 7–25). Meyer & Meyer Sport. [Google Scholar]

- Kuckartz, U. (2014). Qualitative text analysis: A guide to methods, practice & using software. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Landis, J. R., & Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33(1), 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnér, S., Larsson, L., Gerdin, G., Philpot, R., Schenker, K., Westlie, K., Mordal Moen, K., & Smith, W. (2022). The enactment of social justice in HPE practice: How context(s) comes to matter. Sport, Education and Society, 27(3), 228–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, S., & Curtner-Smith, M. (2019). ‘You have to find your slant, your groove:’ One physical education teacher’s efforts to employ transformative pedagogy. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 24(4), 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, S., Sutherland, S., & Walton-Fisette, J. (2020). The A–Z of Social Justice Physical Education: Part 1. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 91(4), 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, S., Walton-Fisette, J. L., & Luguetti, C. (2022). Pedagogies of social justice in physical education and youth sport. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, P. (2014). Qualitative content analysis: Theoretical foundation, basic procedures and software solution. Available online: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-395173 (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- McCall, L. (2005). The complexity of intersectionality. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 30(3), 1771–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, S., Raab, A., Höger, B., & Diketmüller, R. (2022). ‘Same, same, but different?!’ Investigating diversity issues in the current Austrian national curriculum for physical education. European Physical Education Review, 28(1), 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, S., & Bode, P. (2018). Affirming diversity: The sociopolitical context of multicultural education (7th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Opstoel, K., Chapelle, L., Prins, F. J., de Meester, A., Haerens, L., van Tartwijk, J., & Martelaer, K. d. (2020). Personal and social development in physical education and sports: A review study. European Physical Education Review, 26(4), 797–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philpot, R., Gerdin, G., Smith, W., Linnér, S., Schenker, K., Westlie, K., Mordal Moen, K., & Larsson, L. (2021). Taking action for social justice in HPE classrooms through explicit critical pedagogies. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 26(6), 662–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, S. Q., & Dumay, J. (2011). The qualitative research interview. Qualitative Research in Accounting & Management, 8(3), 238–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlon, D., Baker, K., & Tannehill, D. (2022). Developing a socially-just teaching personal and social responsibility (TPSR) approach: A pedagogy for social justice for physical education (teacher education). Physical Education & Sport Pedagogy, 29(5), 452–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheid, V., & Friedrich, G. (2015). Ansätze zur inklusiven Unterrichtsentwicklung. In S. Meier, & S. Ruin (Eds.), Schulsportforschung: Vol. 6. Inklusion als Herausforderung, Aufgabe und Chance für den Schulsport (pp. 35–52). Logos Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Shelley, K., & McCuaig, L. (2018). Close encounters with critical pedagogy in socio-critically informed health education teacher education. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 23(5), 510–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R., Farias, C., & Mesquita, I. (2021). Challenges faced by preservice and novice teachers in implementing student-centred models: A systematic review. European Physical Education Review, 27(4), 798–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W., Philpot, R., Gerdin, G., Schenker, K., Linnér, S., Larsson, L., Mordal Moen, K., & Westlie, K. (2021). School HPE: Its mandate, responsibility and role in educating for social cohesion. Sport, Education and Society, 26(5), 500–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadt Wien. (2020). Integrations- & Diversitätsmonitor: Wien 2020. Available online: https://www.digital.wienbibliothek.at/wbrup/download/pdf/3658833?originalFilename=true (accessed on 31 August 2022).

- Steyn, M. (2015). Critical diversity literacy: Essentials for the twenty-first century. In S. Vertovec (Ed.), Routledge international handbook of diversity studies (pp. 379–389). Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorjussen, I. M., & Sisjord, M. K. (2018). Students’ physical education experiences in a multi-ethnic class. Sport, Education and Society, 23(7), 694–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinning, R. (2020). Troubled thoughts on critical pedagogy for PETE. Sport, Education and Society, 25(9), 978–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Resolution adopted by the general assembly on 25 September 2015. Available online: https://www.nomos-elibrary.de/de/10.5771/9783748902065/sustainable-development-goals?page=1 (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- United Nations Office on Sport for Development and Peace. (2013). Annual report 2012. Available online: https://www.sportanddev.org/sites/default/files/downloads/unosdp_annual_report_2012_final.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- Universität Wien. (2022). Teilcurriculum für das Unterrichtsfach Bewegung und Sport im Rahmen des Bachelorstudiums zur Erlangung eines Lehramts im Bereich der Sekundarstufe (Allgemeinbildung) im Verbund Nord-Ost. Available online: https://senat.univie.ac.at/fileadmin/user_upload/s_senat/konsolidiert_Lehramt/Teilcurriculum_Bewegung_und_Sport_BA_Lehramt.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Vertovec, S. (2015). Introduction: Formulating diversity studies. In S. Vertovec (Ed.), Routledge International handbook of diversity studies (pp. 1–20). Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Vickerman, P., Walsh, B., & Money, J. (2021). Planing for an inclusive approach to learning and teaching. In S. Capel, J. Cliffe, & J. Lawrence (Eds.), Learning to teach physical education in the secondary school: A companion to school experience (5th ed., pp. 199–215). Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Walton-Fisette, J. L., & Sutherland, S. (2018). Moving forward with social justice education in physical education teacher education. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 23(5), 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J. (2004). Critical inquiry and problem-solving in physical education. In J. Wright, D. Macdonald, & L. Burrows (Eds.), Critical inquiry and problem-solving in physical education (pp. 3–15). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

| Teacher | Teaching Dimensions | Instructional Level | Transfer Level | Overall Strategy | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teacher’s name (pseudonym) | Teaching goals | Reported teaching goals with and without reference to SJPs | Reported teaching practices that aim at transfer. (Due to the limited number of teaching practices that seek transfer beyond the PE setting, I refrained from further subdividing this category into goals, content, didactic–methodical approaches, interactions, and grading.) | Summary of the overall strategy of the teacher | Teacher’s type |

| Teaching content | Reported teaching content with and without reference to SJPs | ||||

| Didactic–methodical approaches | Reported didactic–methodical approaches with and without reference to SJPs | ||||

| Teacher-student(s) interactions | Reported interactions with and without reference to SJPs | ||||

| Grading | Reported grading strategy with and without reference to SJPs |

| Transfer Level | ||||

| Yes | No | |||

| Instructional Level | Yes—adapting sport-related content |  |  |  |

| Yes—promoting social goals |  | |||

| No | Not applicable |  | ||

| Type | Amount |

|---|---|

| Nearly Unengaged | 10 |

| Sport-Centered Adjuster | 3 |

| Values-Oriented Teacher | 1 |

| Comprehensive but Contained | 3 |

| Transformative Practitioner | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Heidrich, F. From Nearly Unengaged to Transformative: A Typology of Austrian Physical Education Teachers’ Approaches to Social Justice. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1068. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15081068

Heidrich F. From Nearly Unengaged to Transformative: A Typology of Austrian Physical Education Teachers’ Approaches to Social Justice. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(8):1068. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15081068

Chicago/Turabian StyleHeidrich, Franziska. 2025. "From Nearly Unengaged to Transformative: A Typology of Austrian Physical Education Teachers’ Approaches to Social Justice" Education Sciences 15, no. 8: 1068. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15081068

APA StyleHeidrich, F. (2025). From Nearly Unengaged to Transformative: A Typology of Austrian Physical Education Teachers’ Approaches to Social Justice. Education Sciences, 15(8), 1068. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15081068