Abstract

Bullying and cyberbullying were the focus of analysis in this study. The purpose of the study was to explore teachers’ perceptions, experiences and strategies in relation to these issues, as well as their training needs. A convergent mixed-methods design was used, consisting of a quantitative questionnaire applied to 224 teachers, 12 semi-structured interviews and a field diary. Quantitative results indicated a high level of awareness of the seriousness of bullying, but a lower perception of self-efficacy in its detection and intervention, especially in digital contexts. The internal reliability of the measured dimensions was high (α > 0.85) and differences were identified according to gender and professional experience. At the qualitative level, diverse meanings of bullying, intuitive teaching practices, institutional barriers and specific demands for applied training were evident. Triangulation confirmed the coherence between sources and revealed the need for a strong institutional architecture to support teaching. It was concluded that teachers require resources, support and ongoing training to take a proactive role in bullying prevention and intervention.

1. Introduction

Bullying and cyberbullying have become central to contemporary debates in education due to their persistence and psychosocial consequences, both short- and long-term. They have a clear impact on a range of factors: academic performance, mental health, victims’ self-esteem and group cohesion in the classroom, hence tackling them has become a priority in school systems. In this context, teachers occupy a unique position not only as agents of intervention, but also as key observers in the school microclimates in which this violence persistently takes place.

Educational research has shown that the role of teachers is crucial for the early detection, prevention and effective management of bullying among peers. However, it has also shown that this role is influenced by multiple factors: the teacher’s personal characteristics, experience, training, institutional conditions and the school culture in which they work (Baraldsnes & Caravita, 2025).

In particular, cyberbullying poses additional challenges for teaching teams, as it transcends the physical boundaries of the classroom, operates in the digital space and is often invisible to adults. Its anonymity, mass dissemination and continuity outside school hours generate a sense of helplessness in many teachers, who recognise that they feel ill-equipped to identify it and act effectively (Mishna et al., 2022b).

In a systematic review, Betts and Spenser (2017) concluded that a significant proportion of teachers have conceptual difficulties in clearly defining cyberbullying, which compromises the consistency of institutional responses. These conceptual gaps also contribute to the lack of specific protocols or their inapplicability when cases do not fit typical patterns of victimisation.

Recent literature has evidenced a diversity of teachers’ attitudes towards bullying, ranging from downplaying the conflict to active intervention. This variability is related to both individual perceptions and contextual factors, such as institutional support, school policies or family pressure (Dawes et al., 2024).

Malamut et al. (2025) conducted international research that demonstrated how teachers’ intervention intentions fluctuate significantly depending on whether the case at hand involves gender, race, disability or sexual orientation bias, revealing the existence of implicit judgements that affect the fairness of teacher performance.

One of the most relevant findings in the contemporary literature is the low level of situational awareness that many teachers display in the face of bullying incidents. Malamut et al. (2024) observed that low sensitivity to subtle or indirect cues limits early detection, allowing the dynamics of violence to be perpetuated over time.

Qualitative analysis of teacher narratives has contributed to understanding how the meanings attributed to bullying do not only respond to institutional definitions, but to personal interpretations influenced by professional background, previous experience, ethical frameworks and pedagogical ideologies (Peabody, 2023; Maran & Begotti, 2022).

In this sense, inclusive practices have emerged as crucial to reducing the incidence of bullying. According to Maran and Begotti (2022), teachers who create classroom dynamics based on cooperation, empathy and mutual respect achieve greater student involvement in managing conflicts and reporting situations of bullying.

The European context has been particularly active in generating anti-bullying policies; however, as Sainz and Martín-Moya (2021) point out, formal mechanisms do not always translate into real practices. The existence of protocols does not guarantee their effective implementation if teachers do not have adequate training and resources.

According to the latest studies, it has been found that 6.5% of students in Spain suffer frequent bullying, while 15.8% are victims several times a month and 10% have avoided going to school out of fear (Save the Children, 2025). In addition to this, the ColaCao Foundation, together with the Complutense University, reports that approximately one student per class (around 6.2%) is a recognised victim of bullying, 2.1% of students identify themselves as aggressors and 10.3% report repeated incidents of cyberbullying in the last two months, with almost half of those affected suffering both traditional and digital bullying (Fundación ColaCao & Universidad Complutense de Madrid, 2025). These updated statistics highlight the sustained prevalence and relevance of both forms of bullying in Spanish schools, providing a solid empirical basis for research into teachers’ perceptions and strategies.

After analysing the results of the interviews and questionnaires, the data points to a persistent disparity between formal anti-bullying frameworks and their practical application in schools. The fact that a significant proportion of students continue to suffer repeated bullying or cyberbullying—as demonstrated by the above incidence figures—underscores the urgency of closing this gap through mandatory, real-life-based professional training for teachers, focusing on early detection and effective response strategies (Fundación ColaCao & Universidad Complutense de Madrid, 2025). In addition, the systematic incorporation of social and emotional learning (SEL) programmes into school curricula could strengthen critical protective factors such as empathy, emotional regulation and moral commitment, and reinforce the impact of policies by combining the development of educators’ skills with students’ resilience.

The ecological model, widely adopted in recent studies, has made it possible to understand bullying as a systemic relational phenomenon. From this perspective, Mishna et al. (2022b) insist on the need to consider the multiple layers that shape interactions: classroom, school, family, community, digital social networks, etc.

Cultural factors also play a role in teachers’ interpretation of bullying. Halah (2023), in a study with Saudi teachers, showed that social, religious and family norms influenced how teachers assess the seriousness of incidents, which in turn determined their willingness to intervene.

Also, variables such as gender and professional experience cause relevant differences. Menabò et al. (2022) found that female teachers tended to adopt a more empathetic, personalised approach to bullying cases, while male teachers tended to apply more punitive or rational approaches.

Institutional structure also plays a decisive role. Zambuto and Martín-Moya (2021) note that schools that promote a culture of peer support, normative clarity and committed leadership facilitate teacher engagement in the face of bullying, while those that do not tend to favour passivity or silence.

In the face of this diversity of factors, Baraldsnes and Caravita (2025) propose an integrative view that allows us to understand how teachers’ individual characteristics, institutional environments and interpretative frameworks interact to shape different ways of dealing with bullying and cyberbullying. This perspective requires in-depth research that gives teachers a voice and places it at the centre of analysis.

The analysis of bullying and cyberbullying from the perspective of teachers is not only relevant, but urgent, given the sustained increase in reported incidents and the complexity of its manifestations. Understanding how teachers interpret, detect and deal with these situations allows us to advance more effective school intervention strategies, designed from the reality experienced in the classroom. This view is even more necessary if we consider that many existing policies are built from normative frameworks that are distant from the daily practices and perceptions of teachers, who are key actors in the institutional response (Dawes et al., 2024; Mishna et al., 2022b).

The general objective of this study is to analyse teachers’ perceptions, experiences and strategies in situations of bullying and cyberbullying at school, in order to understand their role as key agents of detection, prevention and intervention. In doing so, the study addresses a gap in the literature, as teachers’ voices have often been neglected in favour of students’ perspectives and institutional programmes. Specifically, the study aimed to: (1) describe the degree of awareness and knowledge of teachers about the phenomenon; (2) identify patterns of action in different types of bullying; (3) explore the factors that influence their decision-making; and (4) assess the training needs expressed by teachers in relation to prevention and intervention.

In terms of training, the literature shows that teacher training on maintaining classroom harmony, bullying and the ethical use of technology is limited or uneven, depending on national contexts and the degree to which schools are involved (Halah, 2023; Peabody, 2023). While there are general lines of action at European and Latin American levels, the success of these initiatives depends largely on how they are understood, harnessed and applied by teachers (Sainz & Martín-Moya, 2021). This dissonance between policy design and actual educational practice has been identified as one of the main challenges in the fight against bullying.

Furthermore, a review of recent research highlights the need to incorporate teachers’ voices in the design of preventive interventions and policies. Maran and Begotti (2022) highlight that measures emerging from participatory processes result in greater involvement, sustainability and effectiveness. In this sense, exploring how teachers interpret and deal with bullying and cyberbullying is not only a descriptive issue, but an indispensable basis for transforming the institutional practices and structural conditions that allow this phenomenon to persist.

With this approach, the study aims not only to provide an in-depth contextual understanding of the role of teachers in bullying, but also to provide an empirical basis for strengthening school policies and teacher training processes, in line with current recommendations in the scientific literature (Baraldsnes & Caravita, 2025; Malamut et al., 2025).

Teachers are fundamental in structuring the prevention, detection and management of bullying and cyberbullying in school contexts. Beyond their instructional role, teachers have a direct influence on the classroom climate, shaping a model of class harmony and the institutional response to peer violence. Recent literature has highlighted that teachers not only observe or intervene in these situations, but also make sense of them according to their experience, teaching ethos and the institutional conditions in which they work (Maran & Begotti, 2022; Peabody, 2023).

Several studies have shown that teachers’ performance is not uniform and is conditioned by multiple factors. These include training received, perceptions of self-efficacy, the type of relationship with students and the level of institutional support they perceive for the intervention (Dawes et al., 2024; Zambuto & Martín-Moya, 2021). In contexts where there are clear policies, committed school leadership and spaces for professional support, teachers are more likely to take an active role in dealing with bullying. On the contrary, in environments where a culture of silence or fear of reprisals prevails, they often opt for evasive or minimal intervention strategies.

With regard to cyberbullying, the role of teachers becomes even more complex. The intangible and transmedial nature of this type of bullying poses significant barriers to recognising and addressing it. Betts and Spenser (2017) identified that many teachers failed to clearly distinguish the boundaries between digital conflict and cyberbullying, which directly affected their ability to respond. This conceptual mismatch is not only due to a lack of training in digital skills, but also to a traditional conception of bullying as an exclusively physical or verbal phenomenon in the school environment.

Faced with this situation, fostering a preventive, proactive teaching approach has been proposed, whereby teachers assume a role of ethical, transformative leadership within the educational community. Such an approach implies not only intervening in cases that have already occurred, but also creating inclusive, relational and participatory classroom structures that limit the conditions conducive to bullying (Malamut et al., 2024; Sainz & Martín-Moya, 2021). To this end, it is essential to provide teachers with theoretical, methodological and reflective tools that enable them to act safely and coherently in complex scenarios.

However, the literature also warns that teachers should not be overburdened or deemed solely responsible. Baraldsnes and Caravita (2025) insist that effective intervention against bullying requires strong institutional architecture, combining ongoing training, collegial support, clear protocols and committed management. From this perspective, the teacher emerges as a key, but not isolated, actor in a network of educational co-responsibility that must be established in a structured, consistent way.

Specifically, the study does not intend to generate exhaustive policy recommendations, but rather to offer empirical evidence that can serve as a foundation for future work on strengthening school policies and teacher training.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study adopted a mixed-methods approach, integrating quantitative and qualitative data with the aim of exploring in depth the manifestations of bullying and cyberbullying from the teachers’ perspective. The decision to use a mixed design was based on the need to complement the statistical analysis of general patterns—drawn from the questionnaire applied to a significant sample—with a richer, more contextual understanding of teachers’ experiences, obtained through semi-structured interviews and a field diary. This type of design allowed triangulation of data obtained from different methods, strengthening the internal and external validity of the results (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018).

From the pragmatic paradigm, a convergent parallel mixed-methods design was used, in which the collection and analysis of qualitative and quantitative data were carried out independently and simultaneously, in order to later compare, contrast and interpret the findings jointly. The quantitative phase consisted of the application of a self-administered questionnaire with 224 valid responses, analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics v29 statistical software. This instrument collected data on teachers’ perception of bullying manifestations, action protocols, perceived self-efficacy, training needs and institutional response.

In parallel, a qualitative analysis was carried out through in-depth interviews with a purposive sample of practising teachers (n = 8), together with a focus group of four participants and a corpus of observations and reflections collected in a teacher field diary. All this material was processed with ATLAS.ti v23 software, using open, axial and selective coding (Strauss & Corbin, 2002), guided by Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) systemic ecological framework and the hermeneutic approach to interpretation.

The choice of a mixed design was also justified by the multidimensional nature of bullying and cyberbullying, phenomena that involve multiple levels of analysis (interpersonal, institutional, social and technological), and whose understanding requires both generalisable evidence and contextualised individual voices (Tashakkori & Teddlie, 2020). This approach was particularly relevant given the applied purpose of the study, which focused on detecting gaps in training and proposing specific lines of educational intervention based on the professional experience of teachers.

2.2. Participants and Sampling

The total sample of the study consisted of 224 practising teachers who participated in the quantitative phase through a self-administered questionnaire, and 12 teachers who took part in the qualitative phase through individual interviews, as well as 4 participants in a focus group. A systematic reflective field diary, constructed by a collaborating teacher based on her direct experience in six different schools, was also incorporated. Given the modest number of participants in the qualitative phase, this part of the study should be regarded as exploratory and cannot be generalised beyond the specific contexts analysed. All the participants carried out their professional activity in the Spanish education system, from pre-school to compulsory secondary education in public schools (i.e., state schools), state-subsidised and private schools, in urban, rural and semi-urban contexts.

For the quantitative phase, non-probabilistic convenience sampling was used, based on the questionnaire that was distributed via online professional networks, educational platforms and institutional channels. The inclusion criteria were being in active practice at the time of answering the questionnaire, and consenting to participate voluntarily and anonymously. Although we did not aim to obtain a statistically representative sample, the data collected allowed us to explore general trends in teachers’ perceptions of bullying and cyberbullying, as well as their training needs in terms of how to deal with them.

The qualitative phase was designed based on purposive and theoretical sampling (Strauss & Corbin, 2002), seeking to capture the diversity of experiences and positions among teachers with mixed institutional backgrounds, varied training in how to maintain harmony, and previous involvement (or lack of) in real situations of bullying. From the analysis of the interviews and the focus group, recurrent emerging categories were identified, which confirmed theoretical saturation of the discourse (Creswell & Poth, 2018).

The educational context reflected in the qualitative accounts was particularly illustrative, documenting real cases, institutional omissions, concealment practices by management teams, as well as a lack of initial and continuing training. The field diary, categorised by core themes (knowledge, detection, intervention, training demands), provided a cross-cutting framework for comparing and interpreting the results with a high level of reflection, in accordance with the principles of hermeneutic qualitative analysis (Flick, 2015).

2.3. Instruments

Data collection shown in Table 1 was carried out through the application of four distinct and complementary instruments: a structured questionnaire, semi-structured interviews, and a reflective field diary. This combination allowed us to triangulate the data from a convergent methodological perspective, generating both quantifiable evidence and interpretative accounts of the phenomenon of bullying and cyberbullying at school.

Table 1.

Structure of the teacher questionnaire with response options.

The main instrument for the quantitative phase was a self-administered questionnaire in digital format, designed ad hoc based on the review of specialised scientific literature, institutional recommendations (Sainz & Martín-Moya, 2021; Baraldsnes & Caravita, 2025), and validated by expert judgement. It had closed-ended items on a 5-point Likert-type scale (from “do not agree at all” to “strongly agree”), grouped into five dimensions: conceptual understanding of bullying and cyberbullying, detection skills, prevention strategies, incident intervention and assessment of the training received. It also included demographic questions on gender, age, autonomous community, educational level, employment status and years of teaching experience. The responses (n = 224) were analysed with IBM SPSS Statistics v29, allowing us to obtain descriptive statistics, frequencies and cross analyses relevant to the objectives of the study.

These instruments were validated by a team of five experts belonging to the SMEMIU Research Group (UNED) using a tool containing questions designed for both the questionnaire and the interviews, which featured a Likert scale from 1 to 5, ranging from ‘Very irrelevant/inappropriate’ to ‘Very relevant/appropriate’, as well as a space for comments. With regard to the questionnaire, all questions were rated with a score of 4 or 5. For the interview questions, the score also ranged from 4 to 5, taking into account the suggestions for improvement that had been proposed.

For the qualitative phase, semi-structured interviews were applied to an intentional group of twelve active teachers, from different educational stages, with a diversity of years of experience and training in coexistence. The interview guide was based on the dimensions of the questionnaire, adapted to encourage experiential accounts, reflective analysis and the identification of obstacles and strategies in the face of real or perceived cases of bullying. The interviews were recorded with informed consent and then transcribed in full. The material was processed in ATLAS.ti v23, following open, axial and selective coding procedures (Strauss & Corbin, 2002).

As a complementary technique, a focus group was developed with four teachers from different levels and centres, whose objective was to collectively contrast experiences, perceptions and solutions applied or desired in the face of bullying and cyberbullying. This dynamic made it possible to capture emerging discursive elements that were difficult to detect in individual interviews, as well as to assess consensus and divergence in responsibilities, institutional barriers and preventive practices. The sessions were also recorded, transcribed and subjected to the same analytical procedure.

The fourth instrument used was a reflective field diary, written by a collaborating teacher with more than six years of experience in different schools. The document contained systematic observations and personal assessments of specific situations experienced, as well as analytical comments on the institutional culture, the role of teachers, the response of management teams and training gaps. This source, structured in four analytical categories (knowledge, detection, intervention, and training demands), was integrated as a qualitative documentary unit in ATLAS.ti, allowing the findings to be triangulated with the rest of the instruments from an emic and longitudinal perspective (Flick, 2015).

The articulation between the four instruments responded to the principle of methodological complementarity, ensuring the internal validity of the mixed design through the convergence and contrast between quantitative and qualitative data (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018). This strategy allowed us to understand not only what teachers think about bullying and cyberbullying (Table 2), but also how they interpret, experience and act in specific situations in their professional environment.

Table 2.

Teachers’ Conceptions of Bullying and Cyberbullying.

2.4. Procedure

The fieldwork was carried out during the first semester of the 2023–2024 academic year, organised in three successive, partially overlapping phases: design and validation of instruments, simultaneous application of the quantitative and qualitative phase, and data processing. Each of these stages was executed in line with the ethical principles of social and educational research, including informed consent, confidentiality of information and participant anonymity.

First, a structured questionnaire was designed based on the theoretical dimensions of the phenomenon studied (conceptualisation, detection, prevention, intervention and teacher training in bullying and cyberbullying). The instrument was reviewed by two specialists in school coexistence and an expert in psycho-pedagogical assessment, in order to ensure its content validity. After the proposed adjustments, the form was digitised and hosted on an online forms platform (Google Forms), and subsequently disseminated through professional social networks, educational associations and institutional channels. Data collection was kept open for four weeks, obtaining a total of 224 valid responses, which were downloaded in CSV format and processed using IBM SPSS Statistics v29 software.

In parallel, the qualitative phase of the study was carried out. A purposive group of volunteer teachers was contacted individually, selected according to differences in educational stage, years of experience, institutional context and previous exposure to bullying situations. Each participant was provided with an information sheet detailing the objectives of the study, the use of the data and the conditions of confidentiality, together with an electronically signed informed consent form.

The semi-structured interviews were conducted by video call via secure platforms, with an average duration of 35–50 min. All were audio-recorded with prior authorisation, and then transcribed verbatim for processing in ATLAS.ti v23 software. The interview guide questions addressed perceptions, practices, institutional barriers and training proposals. Anonymity was guaranteed at all times by assigning pseudonyms and suppressing identifying information in the transcripts.

The focus group was organised virtually and involved four teachers from different educational levels. The one-hour session was conducted by the main researcher, who acted as moderator. A structured guideline with open questions was used, previously contrasted with the interview guide, and a digital recording system was used to preserve the material, which was then transcribed and codified.

Parallel to these activities, a reflective field diary, kept by a collaborating teacher over six years of professional experience in various schools, was produced. The document, structured in thematic entries and emerging categories, was considered an additional qualitative input and analysed as a coding unit in ATLAS.ti. This input was key to contextualise certain testimonies and to document institutional situations that were difficult to capture through questionnaires or formal interviews.

In compliance with the ethical standards established by the Ethics Committee for Educational Research, data protection, anonymised treatment of responses and confidentiality of sources were guaranteed. No participants were directly identified, and all documents were stored on encrypted devices with access restricted to the principal investigator.

2.5. Data Analysis

The data was processed following a convergent mixed-methods approach, in which quantitative and qualitative data were analysed in parallel, to be subsequently triangulated in the interpretation and discussion phases. This strategy made it possible to compare and contrast general trends with personal narratives, enriching the understanding of the research phenomenon through methodological complementarity (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018).

In the quantitative phase, the data obtained from the questionnaire (n = 224) were exported from Google Forms to CSV format and processed using IBM SPSS Statistics v29 software. The analysis focused on obtaining descriptive statistics (frequencies, percentages, means and standard deviations) for each of the items grouped into five dimensions: conceptualisation of bullying and cyberbullying, detection, prevention, intervention and teacher training. In addition, non-parametric inferential tests (Chi-square of independence and Mann–Whitney U tests) were applied to explore association between socio-demographic variables (such as level of education taught or years of experience) and teachers’ perceptions of the phenomenon. These tests were selected on the basis of the ordinal level of measurement of the items and the absence of normality in the distribution of the data (verified by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test).

For the qualitative phase, ATLAS.ti v23 software was used as the main analysis tool. The data analysed included twelve semi-structured interviews, one focus group session and a reflective field diary. The methodological procedure adopted was based on constructivist grounded theory, using open, axial and selective coding (Strauss & Corbin, 2002). Initially, a system of emergent codes was elaborated from an exploratory reading, which was subsequently organised into major analytical categories: teaching knowledge, detection barriers, intervention practices, institutional culture and training needs.

Theoretical saturation was reached progressively by observing the recurrence of key thematic contents in different cases and contexts. This saturation was corroborated by means of a record of code frequency and the lack of new significant categories arising in the last units analysed. In addition, a peer debriefing process was applied in which an external researcher reviewed the coding system, generating thematic concordance of over 90%.

The final integration of the results followed a methodological triangulation procedure in which quantitative and qualitative data were systematically compared in order to identify coincidences, divergences and interpretative tensions. This strategy was justified by the need to offer a deeper, holistic, contextual view of the role of teachers in bullying and cyberbullying, overcoming the limitations of purely descriptive or quantitative approaches (Flick, 2015).

3. Results

The results obtained are organised according to the theoretical dimensions established in the design of the instrument and the objectives of the study. Firstly, the findings from the quantitative analysis carried out using SPSS (v.29) are presented, focusing on the distribution of frequencies, measures of central tendency and contrast of socio-demographic variables with teachers’ perceptions of bullying and cyberbullying. Subsequently, the results of the qualitative phase are addressed, resulting from the thematic analysis carried out with ATLAS.ti (v.23) from semi-structured interviews, a focus group and the field diary.

The presentation of the quantitative data is structured in five blocks: (1) conceptual understanding of the phenomenon, (2) detection capacity, (3) attitudes towards prevention, (4) responses to intervention, and (5) assessment of the teacher training received and needed. For each, statistical descriptions accompanied by contextual interpretation are provided.

In the qualitative phase, emerging categories were identified that enrich and complement the numerical data, providing a deeper understanding of how teachers interpret, confront and evaluate their own skills and limitations in the face of bullying and cyberbullying. The triangulation of sources allowed us to compare and contrast general trends with personal narratives that offer relevant nuances for discussion.

3.1. Descriptive Analyses

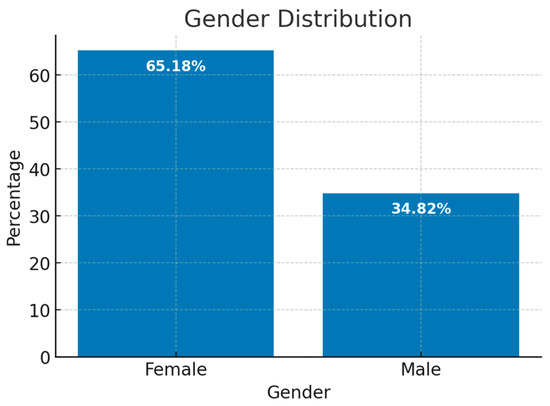

- Gender

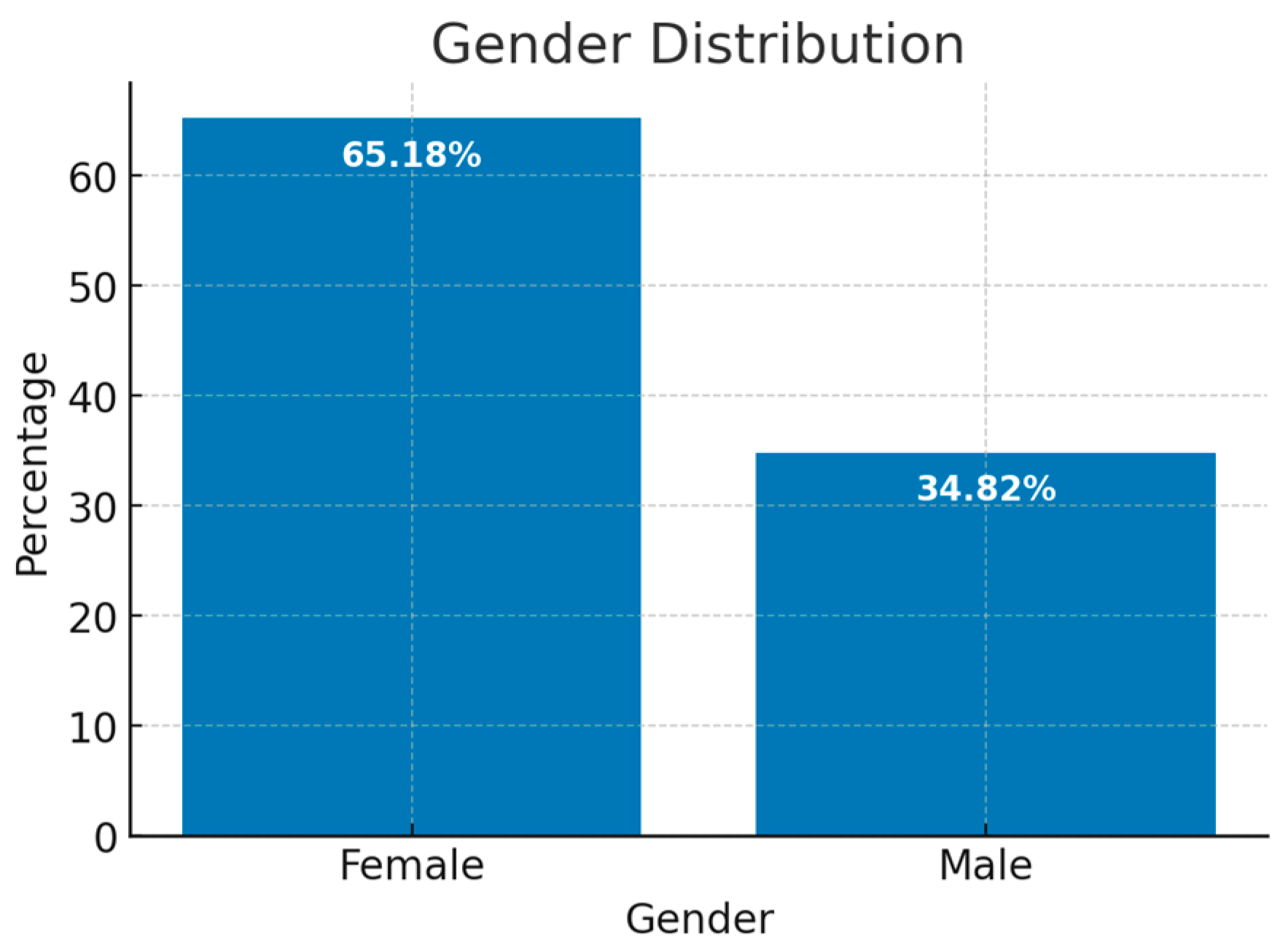

As illustrated in Figure 1, the gender distribution of the participants reflects the predominance of women within the teaching profession in Spain. The sample is mainly composed of women (65.18%), which is coherent with the historical feminisation of the teaching profession in the Spanish context. Men represent 34.82% of the total number of participants.

Figure 1.

Gender.

- Age

As shown in Figure 2, teachers between 42 and 65 predominate, with 32.14% in each of the two age groups (42–53 and 54–65), followed by the 30–41 age group (27.68%). The younger (18–29 years) and older (66 years and older) age groups are less represented, reflecting a teaching body with accumulated experience and professional maturity.

Figure 2.

Age distribution.

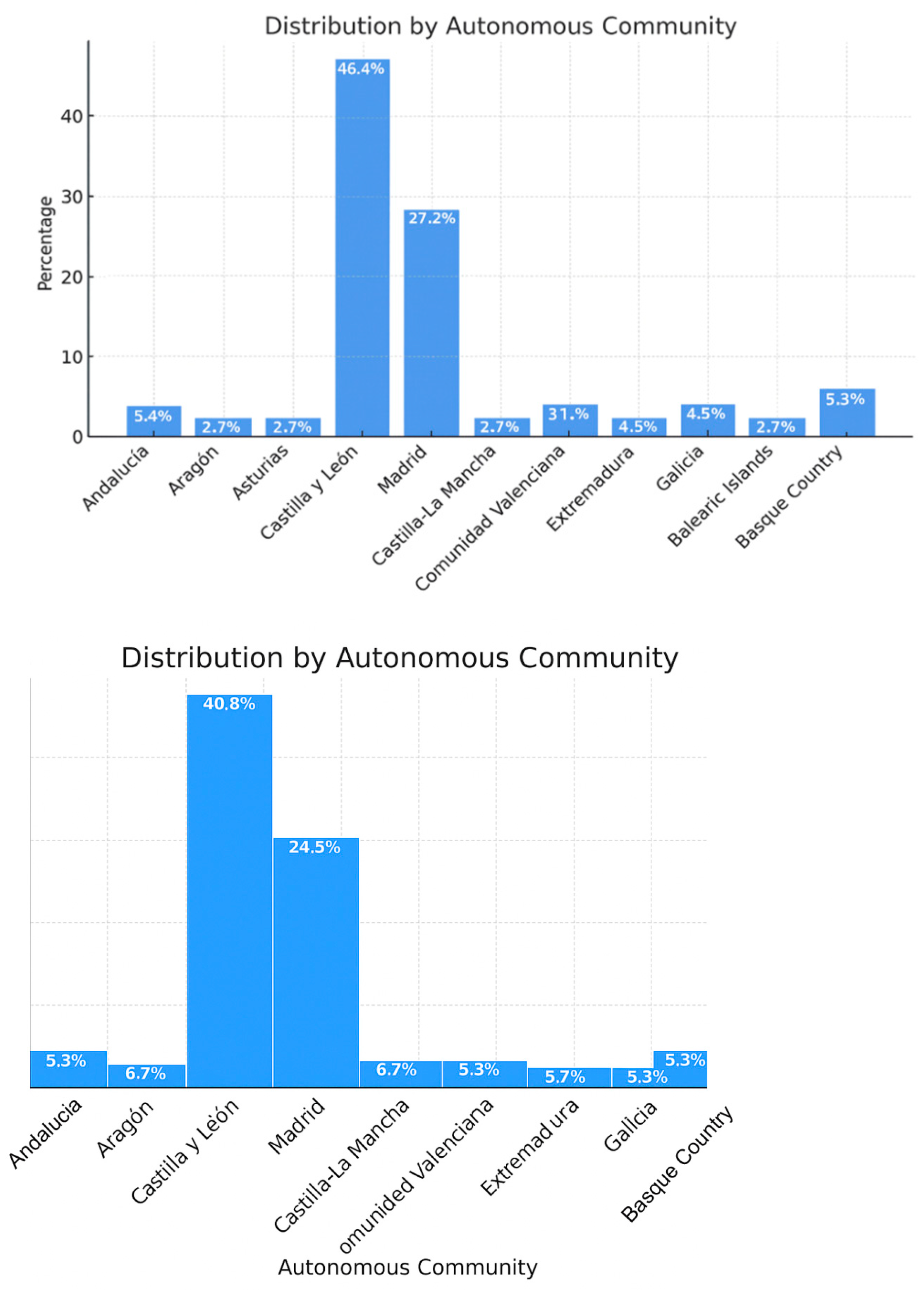

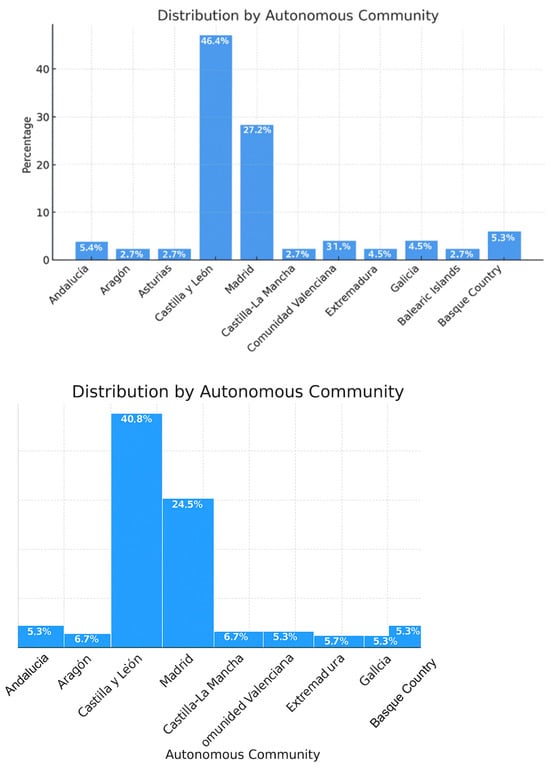

- Autonomous Community

As illustrated in Figure 3, most of the responses come from Castilla y León (46.43%), followed by the Community of Madrid (27.23%). The remaining communities are represented in minority proportions, which shows a significant territorial concentration in the centre-north of the country.

Figure 3.

Autonomous Community.

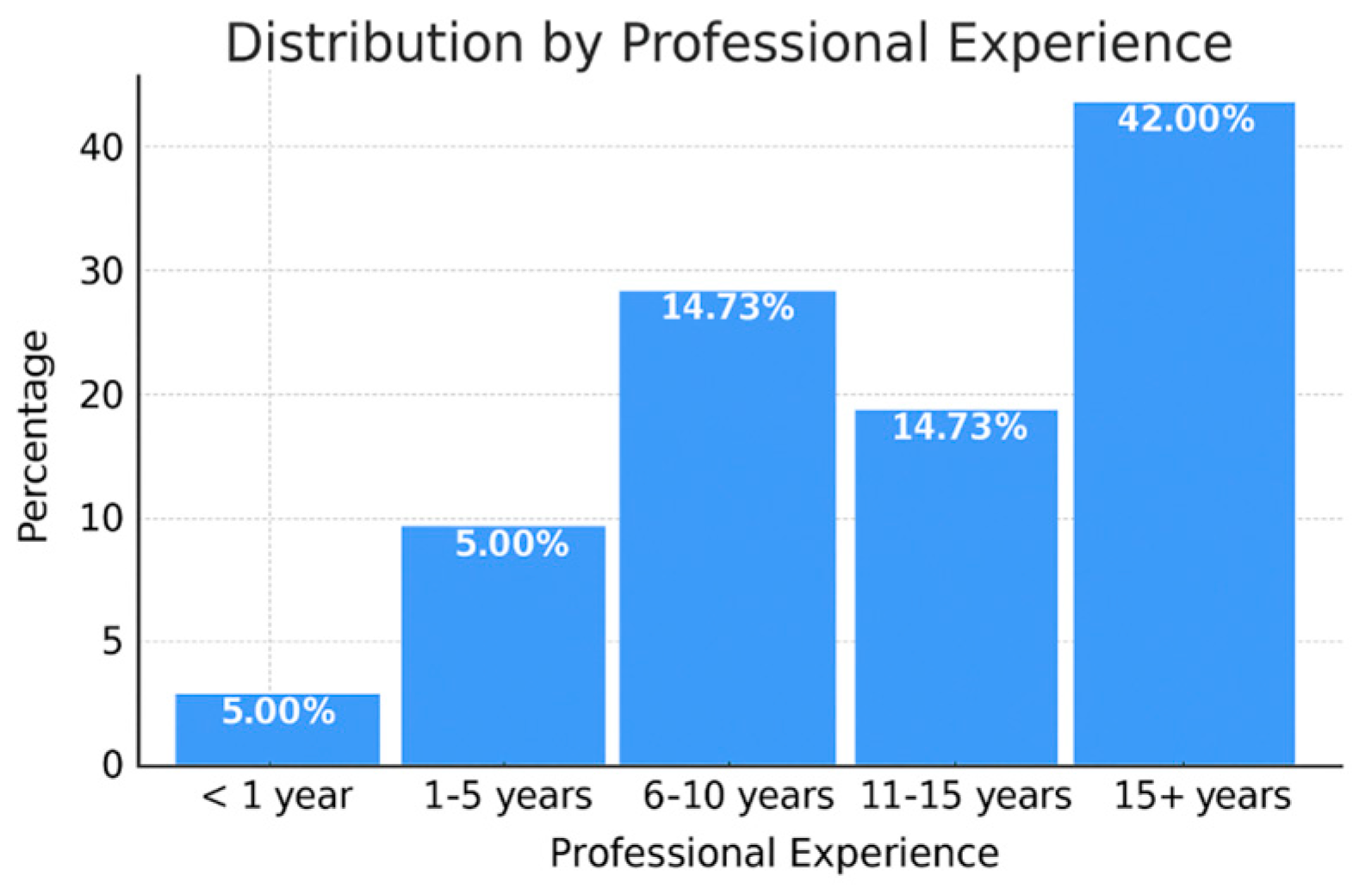

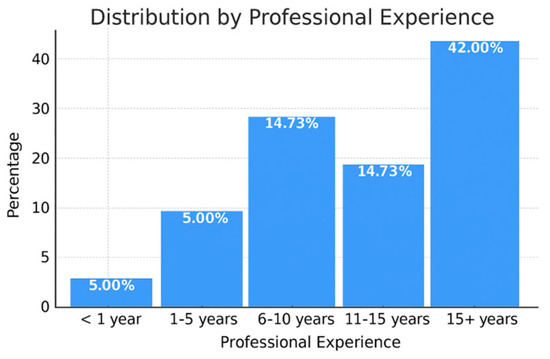

- Professional experience

Figure 4 displays teachers’ years of professional experience. The group with more than 15 years of experience constitutes the highest percentage (42.86%), followed by those with between 5 and 10 years (22.32%). This reinforces the trend observed in the age variable and suggests a sample composed of professionals with a consolidated trajectory in the educational field.

Figure 4.

Professional experience.

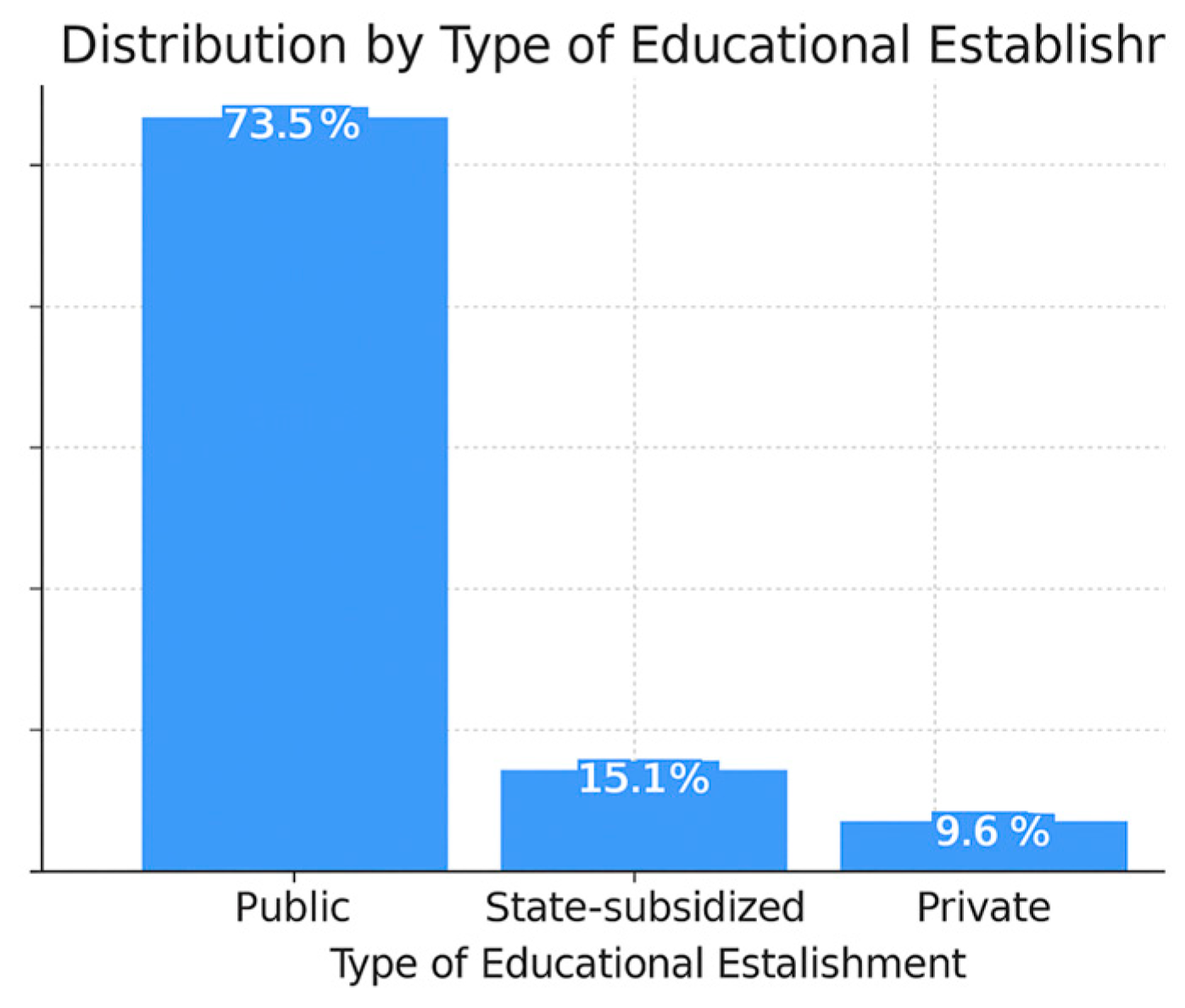

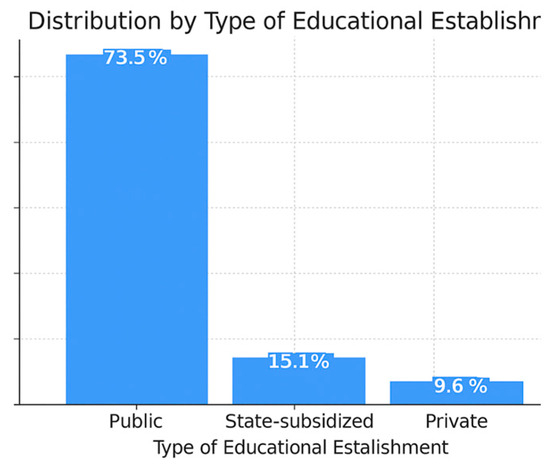

- Type of educational establishment

Figure 5 reflects that most participants work in public schools.Three out of four participants work in public schools (75.45%), while state-subsidised and private schools have lower percentages (15.18% and 9.38%, respectively). This distribution is representative of the Spanish education system, where the public network is home to the majority of students and teaching staff.

Figure 5.

Type of educational establishment.

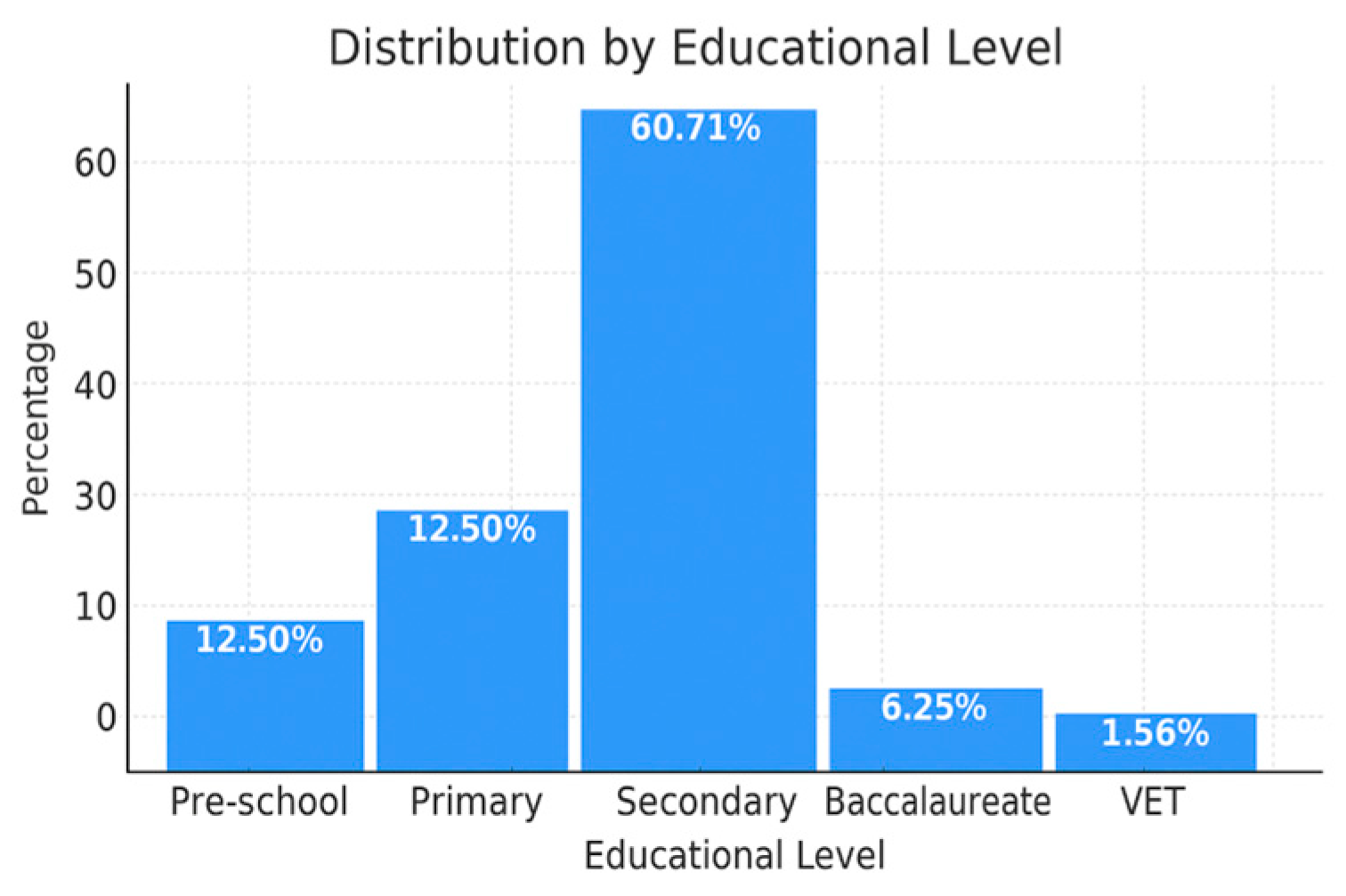

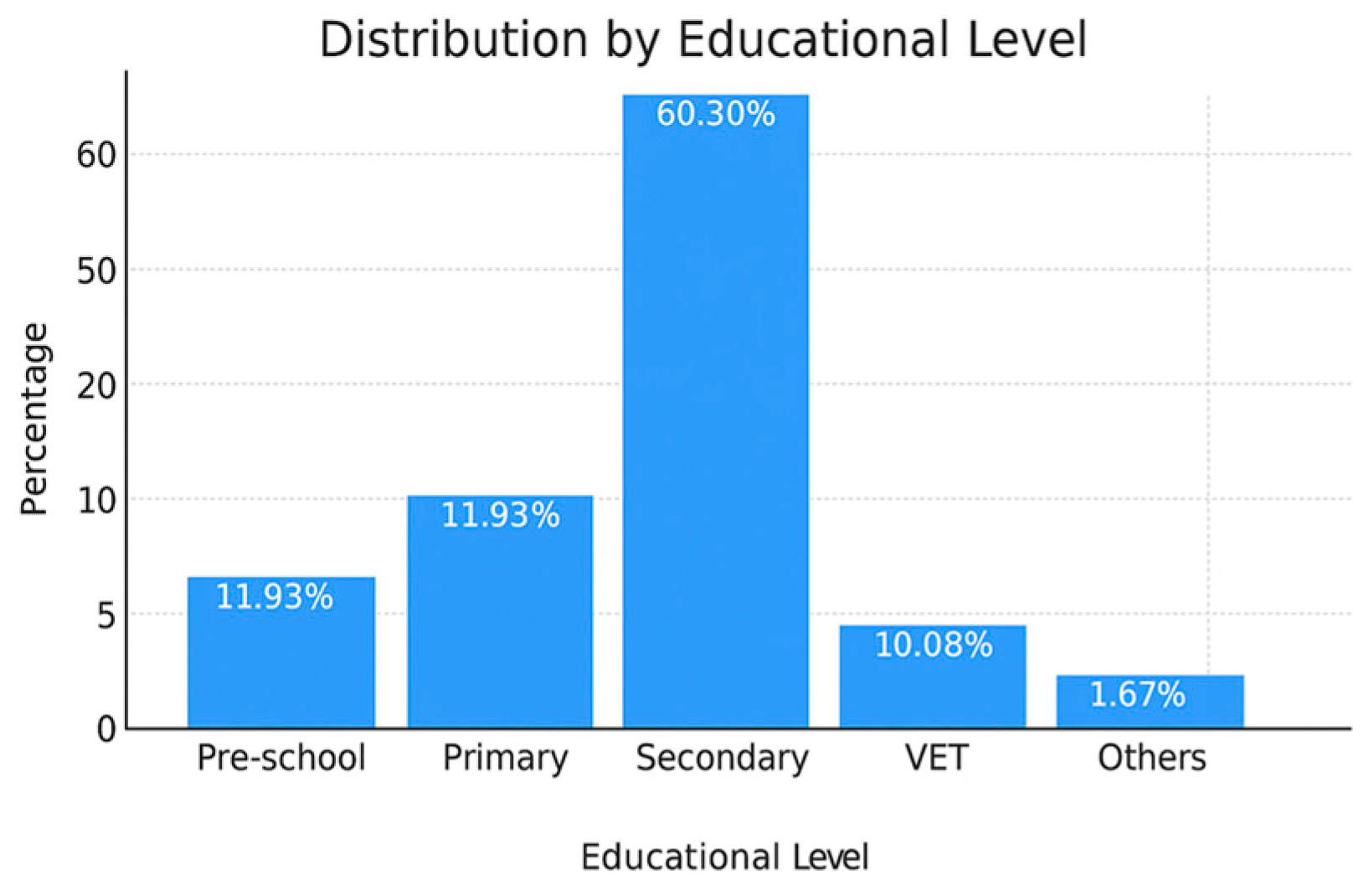

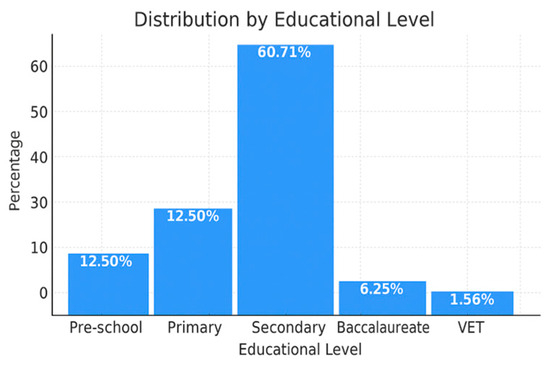

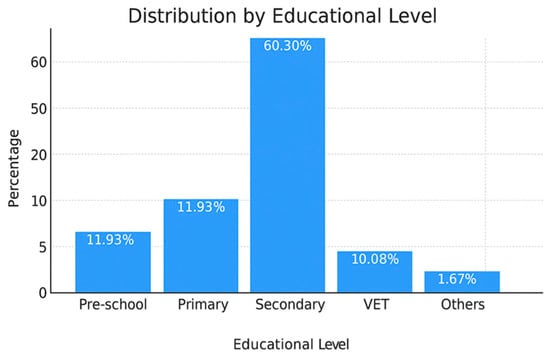

- Educational level at which they work

Figure 6 illustrates the educational levels at which teachers work. The predominant level of professional practice is secondary education (65.63%), followed at a distance by pre-school or primary education (12.95%). Other levels such as baccalaureate, vocational training or intermediate degrees have a reduced representation.

Figure 6.

Distribution by educational level.

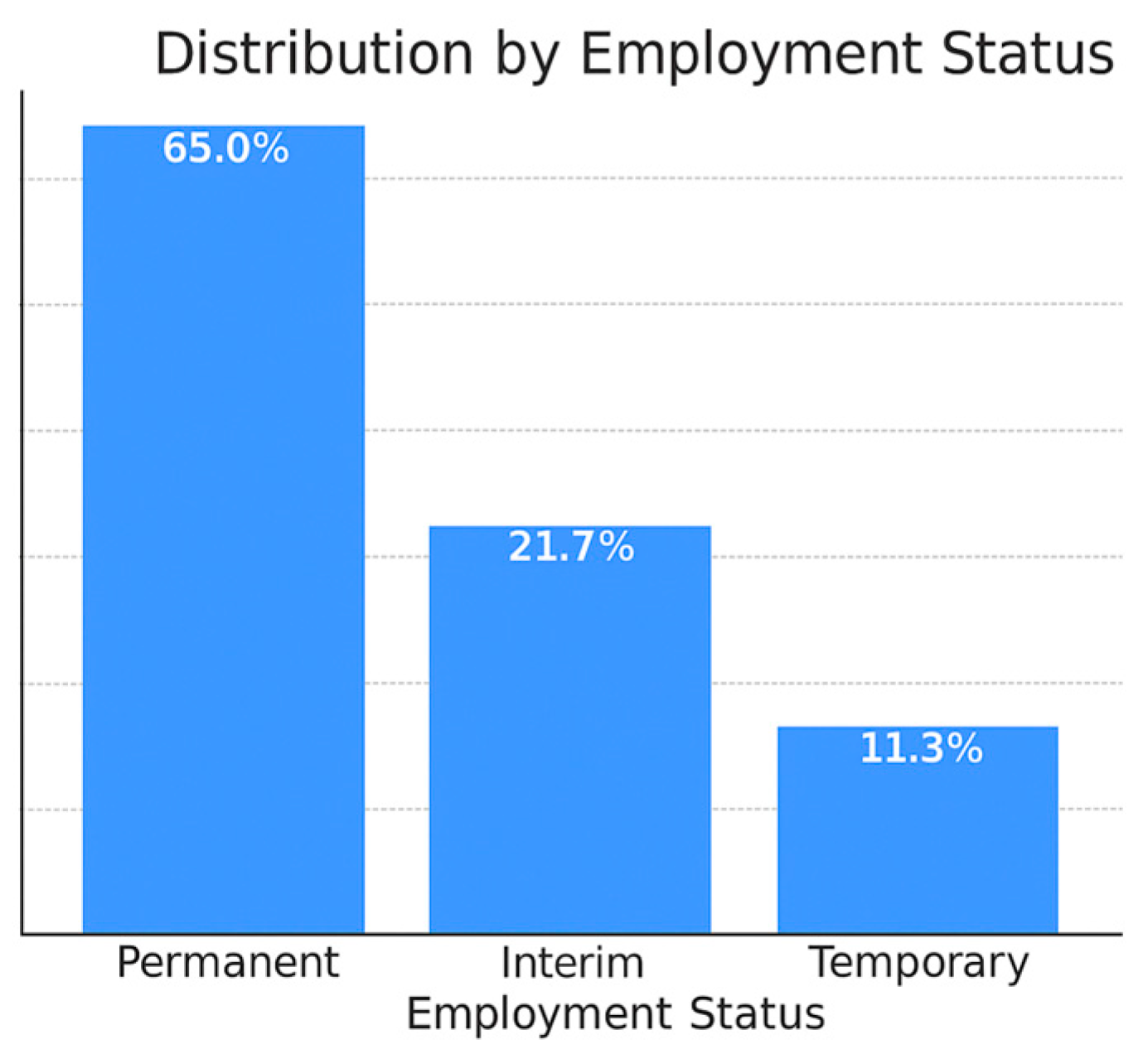

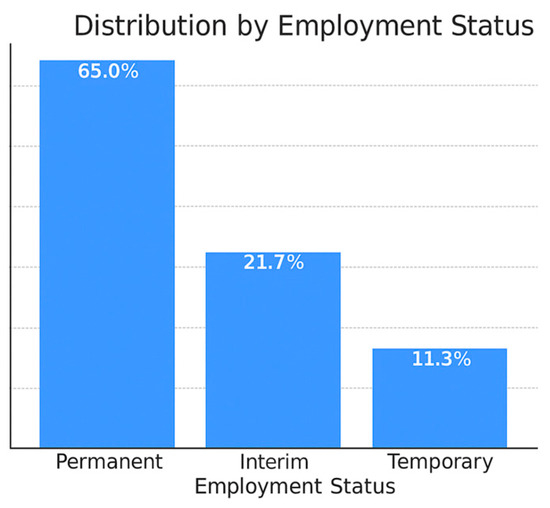

- Employment status

As can be seen in Figure 7, permanent positions predominate.Stability of employment is evidenced by the high proportion of permanent staff (66.96%), complemented by interim (22.77%) and temporary staff (8.48%). Trainee teachers represent a very small fraction (1.79%).

Figure 7.

Distribution by employment status.

3.2. Quantitative Results

3.2.1. Conceptual Understanding of Bullying and Cyberbullying

As shown in Table 3, the results obtained in this dimension reflect a high conceptual awareness among teachers regarding bullying and cyberbullying. In the item on the differentiated understanding between the two phenomena, 67.9% strongly agreed, and a further 21.4% agreed, indicating that almost 90% of the participants clearly recognise this distinction, but this only reflects their subjective perception of their ability, not an objective demonstration of diagnostic skill.

Table 3.

Teachers’ Conceptions of Bullying and Cyberbullying.

Regarding the perception of the seriousness of the problem, the item “Believes that bullying and cyberbullying affect the school environment” obtained 76.3% in the category “strongly agree” and 14.7% in “agree”, which shows a high sensitivity of teachers to the impact of these behaviours

In Table 4 you can see the results in relation to the importance of being informed, 79.9% of teachers strongly agreed and a further 11.6% agreed, which reinforces the value of conceptual training as a basis for intervention.

Table 4.

Importance Attributed to Bullying and Cyberbullying.

Table 5 reflects the reliability analysis, calculated using Cronbach’s alpha—a coefficient that assesses the internal consistency of a set of items designed to measure the same construct—yielded an excellent value (α = 0.904) across the three items. This result justifies their integration as a composite scale of conceptual understanding.

Table 5.

Comparative Analysis of Conceptual Understanding by Sociodemographic Variables.

However, normality tests (Kolmogorov–Smirnov, p < 0.001 in all cases) indicate a non-normal distribution of responses. Therefore, Spearman’s correlation was applied, which revealed significant and moderate associations between the items:

- Between 8.1 and 8.2: ρ = 0.592 (p < 0.001)

- Between 8.1 and 8.3: ρ = 0.531 (p < 0.001)

These results suggest that the three statements are closely related in teachers’ perceptions, supporting the internal validity of the block.

3.2.2. Detection Capability

The data obtained in this dimension show a moderate self-perception of teachers’ ability to detect bullying (Table 6) and cyberbullying (Table 7). On the item “Feels able to identify signs of bullying”, 37.1% agreed and only 14.7% strongly agreed, while a considerable part (37.9%) opted for a neutral position. This trend is repeated in the item on familiarity with signs of cyberbullying, where 35.7% chose the option “neither agree nor disagree”, and only 13.4% expressed total agreement.

Table 6.

Teachers’ Self-Perceived Ability to Detect Bullying.

Table 7.

Teachers’ Self-Perceived Ability to Detect Cybergbullying.

However, the majority recognised that it is essential to be vigilant in cases of bullying: 69.2% responded “strongly agree” and another 17.4% “agree”. This discrepancy suggests that although awareness of the importance of the issue is high, perceived self-efficacy is not equally high.

Almost all participants agreed with the statement about the importance of being vigilant in cases of harassment, with 69.2% in favour. In contrast, only 2.2% disagreed somewhat, while 11.2% took a neutral stance. These results highlight a broad consensus on the importance of being vigilant in situations of harassment (Table 8).

Table 8.

Teachers’ Attitudes Towards Vigilance.

The composite index of the three items exhibited an acceptable level of reliability (Table 9 and Table 10), as indicated by a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.766. This value reflects an adequate degree of internal consistency among the items, thereby supporting their joint consideration and justifying their use as a composite measure in the analysis.

Table 9.

Composite Reliability of Detection Items.

Table 10.

Comparative Analysis of Detection Capability by Gender.

Normality tests (Kolmogorov–Smirnov, p < 0.001) indicate that the three items do not follow a normal distribution, so non-parametric tests were applied.

3.2.3. Prevention of Bullying and Cyberbullying

The results show that teachers have a markedly positive attitude towards bullying prevention in schools. On the item ‘Prevention should be a school priority (Table 11), 58.0% strongly agreed and a further 27.2% agreed.

Table 11.

Prevention as a School Priority.

A similar distribution was observed for the item on the teaching role in social and emotional skills (Table 12), where 61.2% selected the option “strongly agree”, suggesting a clear perception of active responsibility on the part of teachers.

Table 12.

Teachers’ Role in Developing Social–Emotional Skills.

The item with the greatest consensus was “Collaboration between teachers, parents and students”(Table 13), where 74.1% responded “strongly agree” and another 16.5% “agree”. These data reinforce the idea that teachers see tackling bullying as a shared task, in which the educational community must act in a coordinated way.

Table 13.

Family-School Collaboration.

The block of items related to the dimension ‘perceived prevention’ demonstrated high internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.857. This result indicates strong reliability of the set, supporting the validity of the joint analysis of the three items and justifying their treatment as a scale representing this dimension (Table 14 and Table 15).

Table 14.

Comparative Analysis of Prevention Attitudes.

Table 15.

Comparative Analysis of Prevention Attitudes by Teaching Experience.

Tests for normality (Kolmogorov–Smirnov, p < 0.001 for all three items) confirm the non-normality of the data, so non-parametric analyses were used.

When applying the Kruskal–Wallis test to detect differences according to the type of educational institution (public, subsidised or private), no significant results were found (p > 0.05 in all items). This suggests that the valuation of prevention as a key element does not vary according to the type of institution, and can be considered a generalised perception among teachers.

3.2.4. Intervention in Cases of Harassment

The scale referring to teachers’ willingness to intervene in bullying situations showed high internal consistency (α = 0.862), which supports the reliability of the results. This dimension reflects the degree of active involvement and perceived responsibility in the need to act against bullying and cyberbullying.

The sub-block on disciplinary measures showed excellent reliability (α = 0.914), indicating a high consistency in the responses on teachers’ perception of the application of sanctions or corrective protocols in cases of bullying.

The overall bullying intervention index—which groups the different dimensions above—obtained an extremely high alpha value (α = 0.951), suggesting a very strong internal structure and a highly consistent pattern of responses within the teaching staff.

This smaller block showed acceptable reliability (α = 0.750), adequate for two-item scales. The results reflect the teachers’ position on the need to provide support to both victims and perpetrators after incidents.

The Wilcoxon signed-rank test (Table 16) revealed no significant differences between the perceived frequency of use of the criteria for identifying risk profiles and the behavioural observation indicators (p = 0.803), suggesting an equivalent valuation of both elements in schools.

Table 16.

Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test Comparing Risk Profile Identification Criteria and Behavioural Observation Indicators.

3.2.5. Institutional Presence and Teacher Training

The results reveal a generalised perception of inequality in the institutional implementation of measures against bullying and cyberbullying. The Chi-square test (Table 17) identified statistically significant differences in most of the items evaluated, both in relation to intervention strategies and the availability of organisational resources and teacher training. In terms of direct action, significant differences were observed in the willingness to intervene immediately (χ2 = 208.55; p < 0.001), in the assessment of consistent disciplinary measures (χ2 = 252.46; p < 0.001) and in the perception of support for victims and perpetrators (χ2 = 465.11; p < 0.001), which shows a wide variability in the practices and approaches adopted by schools. Differences were also found in the perception of the presence of protocols and tools such as the detection of behaviours in school documents (χ2 = 49.97; p < 0.001), behavioural observation indicators (χ2 = 34.57; p < 0.001), criteria for identifying risk profiles (χ2 = 21.49; p < 0.001), self-reports (χ2 = 16.40; p = 0.003) and screening tests (χ2 = 24 0.75; p < 0.001). However, the use of sociometric questionnaires did not show significant differences (χ2 = 8.37; p = 0.079), which might suggest a limited yet consistent application.

Table 17.

Statistical Comparison of Intervention and Prevention Instruments (Chi-Square Tests).

Regarding structural measures, significant differences were detected in the perception of the presence of prevention programmes (χ2 = 34.39; p < 0.001), intervention strategies (χ2 = 42.21; p < 0.001) and action guidelines (χ2 = 32.43; p < 0.001), behavioural patterns (χ2 = 30.73; p < 0.001) and evaluation methodologies (χ2 = 36.05; p < 0.001), indicating that these elements are not uniformly implemented in the schools. Significant differences were observed in the assessment of university (χ2 = 38.37; p < 0.001) and continuous (χ2 = 32.83; p < 0.001) teacher training, which shows diverse and, in many cases, insufficient training to meet the challenges of dealing with bullying.

3.2.6. Perceived Training Needs

The majority of teachers expressed a high need for training in bullying prevention (Table 18 and Table 19), with 63.4% “strongly agreeing” and 15.2% “agreeing”, reflecting a strong demand for proactive tools to prevent situations of bullying or cyberbullying.

Table 18.

Training needs in bullying prevention.

Table 19.

Training needs in bullying intervention.

In total, 63.8% of teachers strongly agreed with the need for more training in direct intervention, and a further 19.6% agreed, showing widespread concern that they do not have sufficient practical skills to act in an ongoing situation or after the case has been detected.

This item showed the highest percentage of total agreement (64.3%), indicating the perception that teachers prioritise learning concrete strategies and clear procedures to be applied in real situations. It is a central focus of training needs (Table 20).

Table 20.

Training needs in strategies.

In total, 61.6% of teachers strongly agreed that they needed training in behavioural patterns of bullying, reflecting the importance attributed to clear behavioural criteria to act consistently with different student profiles (Table 21).

Table 21.

Training needs in behavioural patterns.

Although slightly lower, 55.8% of teachers expressed full agreement in requiring more training in evaluation methodologies, indicating an interest in improving skills to detect, assess and systematically follow up cases, beyond immediate action (Table 22 and Table 23).

Table 22.

Training needs in evaluation methodologies.

Table 23.

Comparative Analysis of Training Needs in Bullying and Cyberbullying (Kruskal–Wallis Test).

The results of the Kruskal–Wallis test showed no statistically significant differences in any of the five items analysed (p > 0.05 in all cases), indicating that the perceived need for training in prevention, intervention, strategies, behavioural patterns and evaluation methodologies does not vary according to the educational level at which teachers work. This suggests that the demand for training is widely shared and transversal between pre-school, primary, secondary and other stages of education.

3.3. Qualitative Results (ATLAS.ti)

3.3.1. Meanings Attributed to Bullying and Cyberbullying

Central theme: Teachers’ personal conceptions and narratives of what they understand by bullying in its different forms (Table 24).

Table 24.

Teachers’ Perceptions of Training Needs in Bullying and Cyberbullying.

Categorical code matrix: Meanings attributed to bullying and cyberbullying.

- Three broad categories with six main subcategories were generated from the inductive analysis applied to the interviews.

- The quotes reveal varied conceptions: from structured definitions based on power imbalance and intentionality, to more ambiguous approaches in which the boundary between conflict and harassment is blurred.

- An emerging category is the evolution of the notion of bullying over time: several teachers reported that their current understanding of bullying is more nuanced and complex than when they started teaching.

3.3.2. Real Experiences and Barriers to Detection

Focus: Teachers’ perceived barriers to identifying bullying or cyberbullying in the educational environment, including cultural, institutional and technological factors.

Code categorical matrix: Barriers to the detection of bullying.

- Most accounts point to a structural difficulty in observing and confirming bullying, especially when it does not manifest itself physically.

- There is recurrent criticism of the lack of clear protocols and the lack of specialised training to detect early signs, which generates a sense of professional helplessness.

- The culture of silence—both among students and school structures—emerges as a critical barrier to addressing the phenomenon, reinforcing the idea that detection does not depend solely on the will of teachers, but on systemic conditions.

3.3.3. Teaching Strategies and Intervention Frameworks

Central theme: Specific practices that teachers have put in place to intervene in cases of bullying, as well as the perceived limits—personal and institutional—that condition such intervention (Table 25 and Table 26).

Table 25.

Teachers’ Perceptions of Criteria, Indicators and Strategies for the Detection and Intervention in Bullying and Cyberbullying.

Table 26.

Teachers’ Evaluation of Initial and In-Service Training on Bullying and Cyberbullying.

- Teachers show a willingness to intervene, but the strategies applied are often informal, intuitive and not systematised.

- There are strong emotional barriers linked to the fear of acting inappropriately or provoking conflicts with families or the management team.

- The absence of clear institutional frameworks means that responses to bullying depend more on individual judgement than on a common strategy, leading to inequality of care.

3.3.4. Training Demands and Expectations of Teachers

Central theme: Requirements expressed by teachers in relation to their professional preparation, the resources available and the institutional support needed to prevent and intervene appropriately in situations of bullying and cyberbullying (Table 27).

Table 27.

Teachers’ Evaluation of Criteria and Behavioural Indicators for Identifying Risk Profiles.

Categorical matrix of the code: Training demands and institutional support.

- Teachers ask for practical, contextual training, focused on real cases and concrete tools for action.

- A strong expectation of institutional support is evident: without managerial support or coordination, teachers feel unprotected.

- The demands are oriented not only to individual training, but also to the improvement of the organisational structure and resources, which shows a systemic perspective on the solution of the problem.

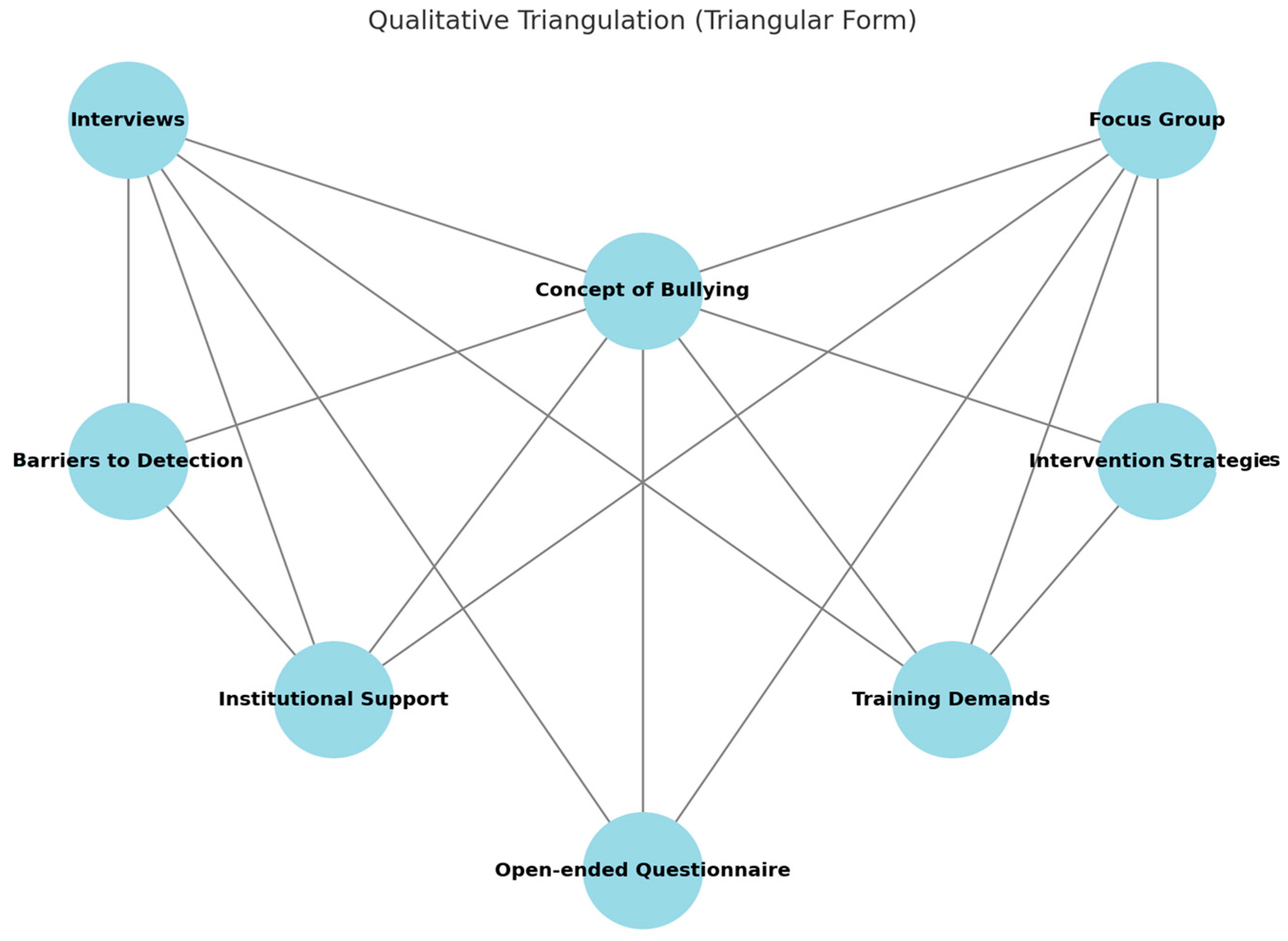

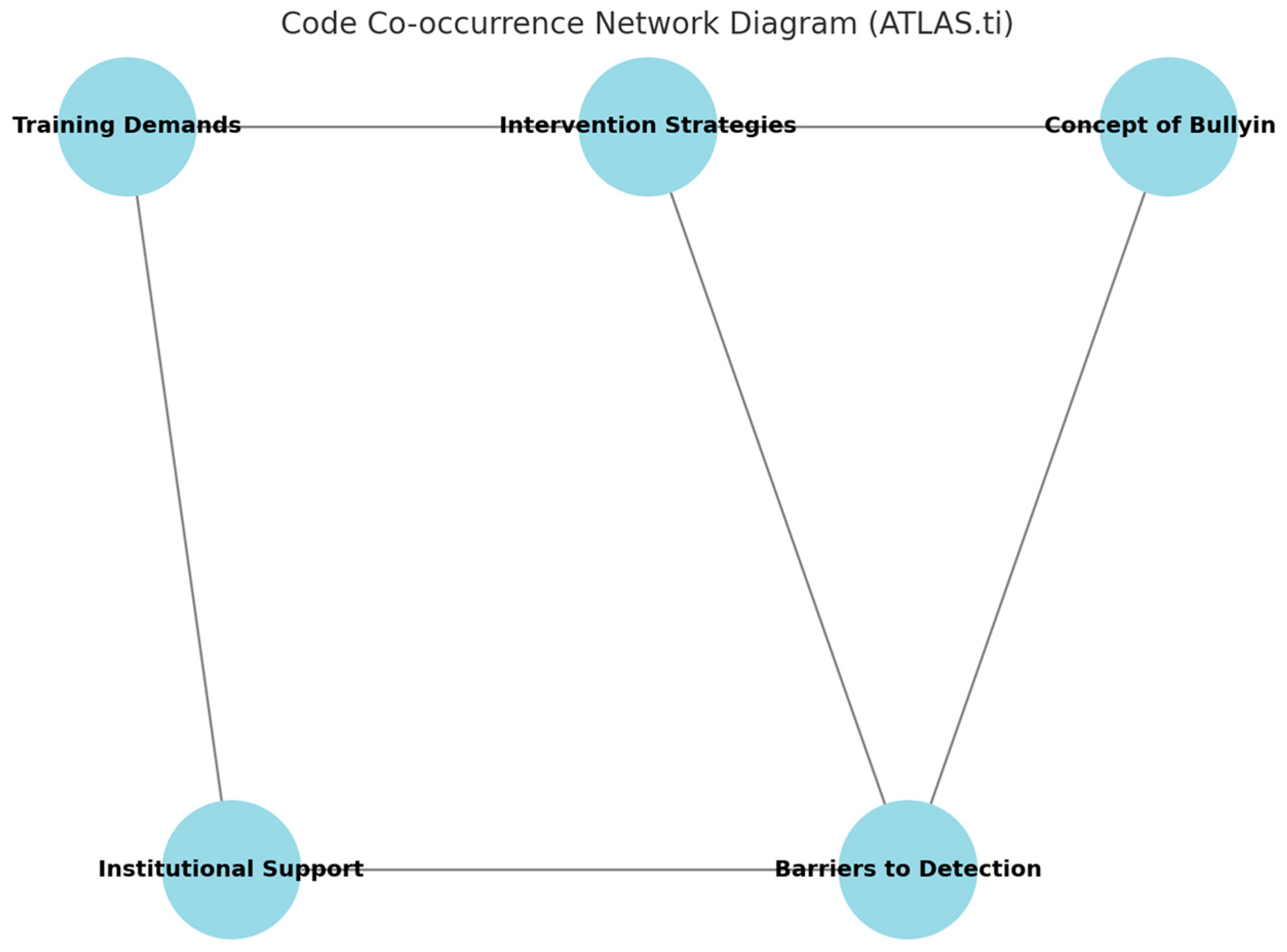

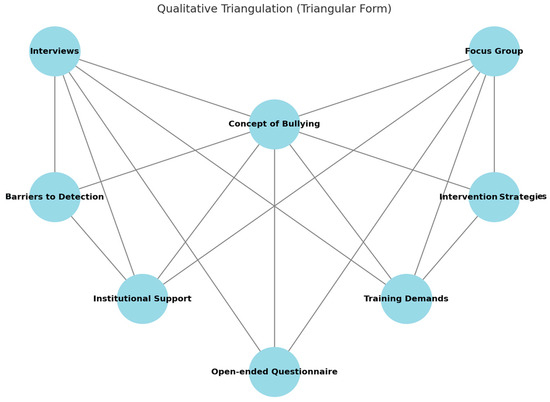

The qualitative analysis was based on the integration of three sources of information: semi-structured interviews with teachers and closed-ended questionnaires, which made it possible to establish a methodological triangulation as shown in Figure 8 that reinforces the validity of the findings.

Figure 8.

Qualitative Triangulations.

3.3.5. Teachers’ Conceptualisations and Barriers to Detection of Bullying and Cyberbullying

The interviews and the focus group consistently identified bullying and cyberbullying as structurally complex phenomena, with both explicit and subtle manifestations. Most teachers defined bullying as a practice sustained over time, based on power imbalance, while the focus group emphasised that the lack of clear conceptual tools hinders its early detection:

“Sometimes they fight and we wonder if it’s bullying or just a conflict between peers.”

“Perhaps if I hadn’t had prior information, I could have considered them as specific problems of coexistence.”

Across all three sources, the lack of specific training and defined protocols clearly emerged as the main barriers. Teachers reported experiences of institutional invisibilisation and lack of coordination, while the focus group denounced the hermeticism of some management teams in the face of real cases:

“We don’t have a clear protocol for action. Everyone does what they can.”

“Everything was dealt with by the head office, but the rest of the teaching staff were not told about it.”

In addition, both individual and collective accounts revealed perceived overlaps between bullying and cyberbullying. Many teachers acknowledged acting on intuition rather than following formal guidelines, often solving cases on the basis of personal experience or common sense. The absence of a shared organisational culture weakens the systematicity of responses:

“I prefer to talk to them before imposing a sanction. Listen first.”

“Addressing the issue through films and questionnaires can help, but it is not enough if there is no institutional follow-up.”

3.3.6. Constant Training Demands

The triangulation revealed complete convergence in the perception of gaps in training. None of the teachers interviewed, nor those who participated in the focus group, had received specific training during their initial training or subsequent professional development.

“They give us lectures, yes, but what we need is to know how to act step by step in a real case.”; “I did not receive any training related to bullying or cyberbullying during my master’s degree.”

The Table 28 suggests a high thematic consistency between the discourse analysed, with very high saturation levels that validate the robustness of the analysis. The small differences detected in the categories of institutional support and training demands raise questions about individual or contextual differences in the understanding of the teacher’s role in the face of bullying. These variations could be further explored in future research, taking into account variables such as professional seniority, type of school or educational level.

Table 28.

Synthesis of triangulation.

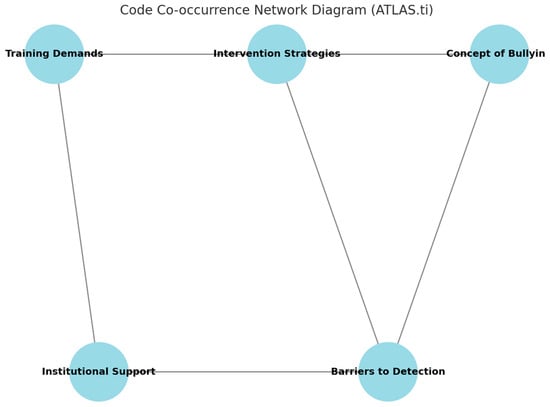

This code show in Figure 9 is connected to barriers, institutional support and training demands, indicating that the way teachers intervene is closely conditioned by the obstacles they perceive and the type of support and training they receive. This centrality confirms their defining role in the teachers’ narrative. The narratives show that an ambiguous understanding of bullying leads to limitations in its early detection. This relationship suggests that conceptual gaps directly affect teachers’ observation skills.

Figure 9.

Code Co-occurrence Network Diagram.

Their connection with barriers and training demands reveals that the perception of organisational support influences both constraints and possible solutions. “Training demands” are not directly linked to the definition of the phenomenon, which reinforces the idea that most of the needs expressed relate to the moment of action, rather than the initial conceptualisation.

4. Discussion

The findings obtained in this research confirm that teachers see bullying and cyberbullying as complex and multifactorial, in line with theories of ecological development (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) and more recent studies on the role of the teacher as a key agent in the identification, prevention and intervention of bullying (Baraldsnes & Caravita, 2025; Maran & Begotti, 2022). This broad understanding of the phenomenon is manifest both in the recognition of the intentional, persistent nature of bullying, and in the difficulty of delimiting it in ambiguous or digital contexts.

The interpretation of bullying as a phenomenon that is often invisible or normalised is supported by previous work highlighting the difficulty for teachers to identify early signs, especially in its digital form (Mishna et al., 2022a; Halah, 2023). Participants in this study reported a lack of specific training and a structural lack of school protocols, which reinforces Peabody’s (2023) point about the urgent need to train teachers in behavioural observation tools and coordinated action strategies.

On the other hand, teachers’ perceived high self-efficacy in their preventive role contrasts with the limited systematic intervention that is evident in practice, marked by intuitive, personal and individualised actions. This tension between teacher commitment and lack of institutional support has been documented in previous reviews (Dawes et al., 2024; Malamut et al., 2024), and is confirmed here through qualitative analysis. It should also be noted that the qualitative phase included twelve individual interviews and a focus group with four teachers, which should be regarded as exploratory and cannot be generalised beyond the specific contexts analysed. This discrepancy may constitute a source of bias, as teachers could provide confident answers in the survey without a fully clear or shared conceptualisation. Accordingly, the qualitative findings should be regarded as a pilot exploration that complements, but does not generalise beyond, the quantitative results. However, this contrast might also be interpreted as a manifestation of attribution bias, in which teachers overestimate their personal contribution while attributing low problem-solving efficacy to institutional factors (e.g., the school as an organisation (REVISION 2). The absence of strong school structures and the fear of reprisals or conflict with families act as barriers to action, increasing teachers’ sense of vulnerability.

From a methodological approach, the complementarity between quantitative and qualitative results coincides with the analytical value advocated by Creswell and Plano Clark (2018) and Tashakkori and Teddlie (2020), who stress that mixed designs allow us to better capture the complexity of the educational phenomenon. In this case, teachers’ perceptions of their own preparedness, together with the institutional limitations pointed out, generate a picture consistent with European studies that warn about the limited effectiveness of school policies when unaccompanied by consistent pedagogical strategies (Sainz & Martín-Moya, 2021).

Teachers also expressed the expectation of receiving continuous training, framed in and adapted to real classroom contexts, a claim that reinforces the literature on teachers’ professional development on issues of social harmony in schools (Menabò et al., 2022; Betts & Spenser, 2017). In particular, there is a demand for a training model that is not limited to theory, but provides contextualised intervention models, practical materials and professional support.

Critically, this study also allows us to observe how teacher intervention is not only limited by a lack of resources, but also by an institutional culture in which bullying is often downplayed, ignored or delegated to other actors. This structural de-responsibilisation has been identified as one of the factors that most weakens the educational response to bullying (Zambuto & Martín-Moya, 2021; Stauffer, 2011). Intervention thus becomes a solitary practice, where the teacher bears a responsibility that is not always shared or supported by the system.

The results corroborate the need to understand bullying and cyberbullying from a holistic approach, which considers not only the student–student interaction, but also the role of the educational institution and its normative, relational and formative frameworks (Malamut et al., 2025; Strauss & Corbin, 2002). The teachers’ perspective not only provides empirical evidence, but also directly challenges the political and administrative frameworks that govern harmony in schools. In addition to confirming previous findings, this research provides new clues for interpreting the phenomenon of bullying from a perspective shaped by the organisational culture of teachers, which allows us to overcome reductionist approaches focused solely on students. In this sense, the study agrees with authors such as Malamut et al. (2024) in demonstrating that teachers act not only as observers, but as emotionally, ethically and professionally involved actors whose actions are mediated by specific institutional structures, values and conditions.

One of the main practical contributions lies in the identification of tensions between perceived self-efficacy and operational efficacy, which makes it possible to question the assumption that awareness of the problem automatically leads to effective intervention. This nuance, little explored in previous studies, opens up the possibility of designing training and support systems that improving knowledge, but also address the cultural and relational conditioning factors that hinder teaching action.

The study also reveals that while there is consensus on the need for ongoing training, the content, format and applicability of such training remain a matter of debate. While some teachers call for standardised resources, others stress the need for context-specific materials with ongoing professional support, which raises the theoretical challenge of how to balance institutional standardisation with personalised intervention strategies (Creswell & Poth, 2018).

In terms of contradictions, although teachers’ discourse is aligned with the principles of active prevention and early detection, in practice we observe forms of structural passivity or delegation of responsibilities, especially when the cases affect students with high conflict profiles or involve tensions with families. This finding challenges the dominant “teacher-vigilante” narrative and suggests the need to rethink the role of the teacher not as a figure of control, but as a critical mediator within complex institutional networks (Strauss & Corbin, 2002).

In terms of the study’s limitations, while the mixed design allowed for a sound methodological triangulation, the qualitative sample concentrated on a small number of schools and regional contexts. This precludes a full generalisation of the results and underlines the importance of future studies with more geographically and socio-culturally diverse samples. Also, although thematic saturation was achieved, interviews with management staff or external figures such as counsellors, whose perspective would be a valuable contrast to teachers’ experiences, were not included.

In future research, it is recommended that collaborative models of intervention be explored, where teachers work together with guidance teams, families and external services. Similarly, it would be relevant to analyse how factors such as workload, organisational climate or teaching experience influence the ability to respond to cases of bullying. Finally, it is suggested that analysis be extended to university training contexts in order to understand how professional skills in dealing with bullying are built from the initial stage of teacher training (Tashakkori & Teddlie, 2020).

5. Conclusions

This study presents several limitations that should be taken into account when interpreting the findings. First, the teacher sample was obtained through non-probabilistic sampling and was territorially concentrated in certain autonomous communities, which restricts the generalisability of the results. In addition, the qualitative phase involved a small number of participants, meaning that their contributions should be regarded as exploratory. Another limitation lies in the reliance on teachers’ self-perceptions, which may not fully reflect their actual classroom practices. Finally, given the cross-sectional design, it was not possible to analyse changes in perceptions and strategies over time, nor to triangulate the results with other perspectives, such as those of students or families.

This study reaffirms that teachers are strategic actors in the understanding and management of bullying and cyberbullying in school contexts. From the mixed-methods approach, we have managed to capture both the quantitative dimension of their perceptions and the experiential depth of their discourse, which has in turn allowed us to identify shared patterns of interpretation, structural barriers and recurrent training demands. The findings show that, although there is a high awareness of the seriousness of the problem, there are still significant limitations in terms of detection capacity, systematic intervention and institutional support.

One of the main practical contributions of this work lies in the need to reconfigure teacher training around specific skills in promoting a peaceful school environment and bullying prevention. This training should go beyond theoretical approaches to include simulations, real case studies, critical analysis of ethical dilemmas and communication strategies adapted to the diversity of students. Moreover, the data analysed suggest that such training cannot be a one-off event, but an ongoing, contextualised process consistent with real classroom dynamics.

Similarly, it is necessary to strengthen institutional frameworks for action. The existence of school protocols must be accompanied by shared lines of action, spaces for professional deliberation and effective channels of communication between teachers, families and guidance teams. Intervention against bullying should be seen as a collective responsibility, where the teacher acts in a network with other agents, without working alone on a task that requires structural support.

As a final recommendation, it is urgent to design educational policies that integrate the perspective of teachers in decision-making, not only as implementers of rules, but also as generators of contextual knowledge. Only through this active inclusion will it be possible to build safer, more sustainable and fairer school environments for the entire educational community. Listening carefully to those who actually experience the classroom on a daily basis is the first step in transforming the conditions that perpetuate school violence and, at the same time, in empowering those who wish to eradicate it.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.B.M.P. and C.S.R.; methodology, E.B.M.P. and C.S.R.; software, E.B.M.P. and C.S.R.; validation, C.S.R.; formal analysis, E.B.M.P.; investigation, E.B.M.P.; resources, E.B.M.P.; data curation, E.B.M.P.; writing—original draft, E.B.M.P.; preparation, E.B.M.P. and C.S.R.; writing—review and editing, E.B.M.P. and C.S.R.; visualization, E.B.M.P. and C.S.R.; supervision C.S.R.; project administration, C.S.R.; funding acquisition, C.S.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Project TED2021-129132B-I00_PROXIMITY CYBERBULLYING: HOW TO AVOID IT THROUGGAMIFICATION WITH THE METAVERSE? Research project TED2021-129132B-I00_PROXIMITY CYBERBULLYING: HOW TO AVOID IT THROUGH GAMIFICATION WITH THE METAVERSE? Funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by the European Union NextGenerationEU/PRTR.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. In accordance with current legislation on educational research in Spain, this type of study does not require approval by an ethics committee as long as the voluntary participation, informed consent and anonymity of the participants is guaranteed, which was fully ensured.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants in the study. In the case of the questionnaire, consent was incorporated at the beginning of the digital form, where the objectives, conditions of participation, confidentiality and use of data were explained. For the interviews, the focus group and the field diary, a detailed information sheet was provided and express consent was obtained in written or digital form prior to the recording and transcription of the sessions.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon reasoned request to the corresponding author. As this is sensitive information from practising teachers, strict anonymisation criteria have been applied. Access to the datasets may be granted for academic purposes, subject to ethical evaluation and a commitment to confidentiality.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest related to the conduct of this study. No financial, institutional or commercial entity has influenced the design of the research, the collection or analysis of the data, the interpretation of the results, or the writing of the manuscript. Likewise, it is affirmed that no professional, academic or personal links are maintained that could partially or totally condition the contents presented here.

References

- Baraldsnes, D., & Caravita, S. C. S. (2025). The relations of teacher use of anti-bullying components at classroom and individual levels with teacher and school characteristics. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betts, L. R., & Spenser, K. A. (2017). Teachers’ perceptions towards cyberbullying: A systematic review. Nottingham Trent University IRep. Available online: https://irep.ntu.ac.uk/id/eprint/34401/1/11833_a1049_Betts.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications. Available online: https://bayanbox.ir/view/236051966444369258/9781483344379-Designing-and-Conducting-Mixed-Methods-Research-3e.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Dawes, M., Malamut, S. T., Guess, H., & Lohrbach, E. (2024). Teachers’ attitudes toward bullying and intervention responses: A systematic and meta-analytic review. Educational Psychology Review, 36, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flick, U. (2015). Introducing research methodology: A beginner’s guide to doing a research project (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Fundación ColaCao & Universidad Complutense de Madrid. (2025). First large-scale study on school bullying and cyberbullying in Spanish childhood and adolescence. Fundación ColaCao. [Google Scholar]

- Halah, A. (2023). Teachers’ perceptions of bullying in Saudi Arabian primary public schools: A convergent parallel mixed-method study. Children, 10(12), 1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malamut, S. T., Dawes, M., & Lohrbach, E. (2024). Teachers’ awareness and sensitivity to a bullying incident: A qualitative study. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 6(1), 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malamut, S. T., Dawes, M., & Lohrbach, E. (2025). An international investigation of variability in teacher perceptions of and intervention intentions in bias-based bullying situations. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 7, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maran, D. A., & Begotti, T. (2022). Teachers and inclusive practices against bullying: A qualitative study. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 31(2), 456–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menabò, L., Skrzypiec, G., Slee, P., & Guarini, A. (2022). What roles matter? An explorative study on bullying and cyberbullying. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 92(4), 1095–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishna, F., Birze, A., & Greenblatt, A. (2022a). Qualitative methods in school bullying and cyberbullying research. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 4(2), 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishna, F., Birze, A., & Greenblatt, A. (2022b). Understanding bullying and cyberbullying through an ecological systems framework: The value of qualitative interviewing in a mixed methods approach. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 4(2), 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peabody, A. D. (2023). A qualitative case study to examine teachers’ perceptions of bullying within K-12 institutions. World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews, 19(1), 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainz, M., & Martín-Moya, R. (2021). School interventions for bullying-cyberbullying prevention in adolescents: A European perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Save the Children. (2025). Breaking the silence on school bullying: National statistics 2025. Save the Children Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Stauffer, S. (2011). High school teachers’ perceptions of cyber bullying: Prevention and intervention strategies. Brigham Young University Scholars Archive. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264121964 (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (2002). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. SAGE Publications. Available online: https://methods.sagepub.com/book/mono/basics-of-qualitative-research/toc?utm_source=chatgpt.com#_ (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Tashakkori, A., & Teddlie, C. (2020). Foundations of mixed methods research: Integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches in the social and behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Zambuto, V., & Martín-Moya, R. (2021). Teachers’ perceptions and position regarding the problem of bullying in schools. Behavioral Sciences, 14(3), 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).