1. Introduction

In the virtual reality era, profound transformations are underway, reshaping the developmental pathways of children and young people as they navigate the intricate terrain of identity formation. In the context of this study, virtual reality can be understood as the contemporary manifestation of technology and the Internet in all their forms, providing individuals with a novel form of existence that blurs the boundaries between the physical and digital realms. With the integration of virtual reality technologies into their everyday lives, individuals are confronted with novel experiences that blur the lines between the physical and the digital realms. This dynamic interplay between the virtual and the real has created an intriguing interconnection between identity and body image, as perceptions of self become intricately woven with digital avatars and simulated environments [

1,

2].

The malleability of avatars and virtual profiles and the potential for customisation often prompt questions about the influence of these digital personas on individuals’ perceptions of their physical bodies. Intriguingly, the amalgamation of virtual and real experiences presents an unprecedented opportunity for educators to foster a holistic understanding of identity that encompasses both the corporeal and the digital. It also offers a valuable opportunity to rethink their educational approaches. Through a nuanced approach to teaching, educators can equip students with the critical skills to navigate the virtual landscape while nurturing a robust sense of self [

3], which is fundamental in a cultural scenario in which identities appear unstable and blurred.

Virtual reality has quickly entered the educational arena, heralding unique opportunities, potential contradictions, and its profound influence on identity development. Incorporating virtual reality into education opens the door to immersive learning experiences beyond the confines of the traditional classroom, allowing students to explore historical events, journey to far-off places, and interact with complex scientific phenomena in ways they could never have imagined before. However, this broadening of educational horizons comes with several paradoxical ideas. Virtual reality has the clear potential to improve education, but it also raises questions about how it will affect how children and young people develop their identities [

4,

5,

6].

The ability of virtual reality to immerse users in alternative realities and provide the opportunity to create idealised digital personas presents a paradox in and of itself. On the one hand, it gives students a place for self-expression and self-discovery and allows them to experiment with various facets of their identities. On the other hand, this malleability might eventually cause the distinction between reality and simulation, creating a gap between a person’s true identity and digital representation. This dissonance might make problems with self-esteem, body image, and a coherent sense of identity worse [

2]. As the lines between the virtual and physical realms become increasingly indistinct, a critical need emerges to untangle the intricate connections between identity formation, body perception, and the immersive capabilities of virtual reality in education. Equally vital is comprehending how to harness the positive opportunities presented by this digital age to propel educational methodologies forward. Furthermore, delving into educators’ role in guiding students through the intricate landscape of virtual existence holds significant importance.

This article delves into these dimensions, shedding light on children and young people’s transformative journey to shape their identities within the captivating realms of the virtual reality era [

4,

5]. By exploring the type of social media use and its potential effects, this study sought to contribute to a deeper understanding of the complex relationship between social media and children’s body image, ultimately informing strategies for promoting positive body image [

6,

7]. The study is based on an exploratory research intervention to investigate the relationship between social media usage and its potential effects on body image development among children aged 9 and 10. The hypothesis posited that the type of social media use, including exposure to idealised body images and altered/filtered images, comparisons with peers, and engagement with body-focused content, would be associated with adverse negative effects on children’s body image and a negative impact on children’s identity. However, an educational intervention aimed at developing what we term “body literacy” among children is expected to counteract these adverse effects.

1.1. Body and Body Image in the Virtual Reality Era

Body image is the personal representation of one’s body, and it can be considered a multidimensional concept used to define a person’s perceptions, feelings, thoughts, and behaviours related to one’s body [

4,

5,

8]. Body image construction begins consistently in early childhood, between the ages of 9 and 12 for girls and between 10 and 13 for boys, and continues throughout preadolescence and adolescence. In parallel, body dissatisfaction may emerge before puberty, as children, even pre-schoolers, can evaluate their body proportions and appearance and compare themselves to body models. As a result, starting from the age of 6, the body’s shape becomes more significant, as studies have shown that a considerable proportion of children aged 6 to 12 admit dissatisfaction with the size or shape of some part of their body [

4,

5,

9]. Hence, childhood emerges as a pivotal phase in the formation of body image, underscoring the need for interventions addressing body dissatisfaction to commence at this early age.

Broadly, body image attitudes are established during early childhood [

10]. This phase provides the foundation for the subsequent formation of the body image. Childhood comprises the period from birth to the onset of puberty/adolescence. This phase is highly relevant since it is configured as the basis of human formation and body image. Throughout life, body image is in permanent (de)construction. Weight concerns, body-related beliefs, and behaviours directed at improving physical appearance may begin during childhood. Thus, from an early age, the individual searching for an ideal body may have his or her body image affected [

11]. At as early as age 3, children frequently internalised body size stereotypes [

12], and children as young as age 5 have expressed body dissatisfaction [

13] and engaged in dietary restraint [

14].

The perception of one’s body often deviates from reality and is significantly influenced by various social factors, including family, peers, and social media. Thompson’s “Tripartite Influence Model” highlights the direct impact of these elements on body dissatisfaction and their indirect impact through two variables: internalisation of the social ideal body type and appearance comparison [

15]. This model provides valuable insights into understanding how these social influences contribute to developing body image issues. One crucial aspect linked to body image is the concept of satisfaction [

16,

17]. Body satisfaction is defined as how one thinks about one’s body. To increase their body satisfaction, pre-teens often engage in social comparisons [

18]. Physical changes during the following puberty phase tend to increase body dissatisfaction [

19,

20]. Improper digital experiences can significantly undermine body satisfaction and body esteem. Compared to others or the ideal standards of beauty perpetuated by the media, individuals’ self-judgment of their bodies may be distorted as a result [

21]. This highlights the powerful influence of digital platforms on shaping individuals’ perceptions of their bodies, often leading to adverse outcomes. Understanding and addressing the impact of these experiences is crucial to promoting healthier body image and well-being. These ideals are considered personal goals and standards and are perceived as real but unattainable.

Nowadays, the early use of social media during childhood has a central role in the onset of body image disorders. They might influence the perception of self, especially those focusing on visual communication, such as Instagram and Snapchat, which convey ideals of beauty and appearance [

22,

23]. In modern times, people spend a huge amount of time online, especially through smartphone use, which has many more features than just making calls and sending and receiving messages. In everyday life, it can be observed that children and youth are the ones who spend the most time on their smartphones surfing the Internet [

24,

25]. Moreover, thanks to the broader availability of at least one Internet-connected device, the time they spend online is increasing quickly, and Internet access is considered anticipated in pre-adolescence. Irrespective of potential age restrictions that may be in effect [

22], children initiate their exposure to social media at a notably young age [

26].

Consequently, this early exposure can give rise to various body-related concerns during the pre-teenage and childhood years [

27]. The proportion of children and young people using social media is very high in Italy. According to the Italian National Statistical Institute (ISTAT) data for 2021, 89.1% of children aged 6 to 10 use social media, and 55.5% use it every day [

28].

In more specific terms, recent research has revealed a significant correlation between social media usage and body image disorders. Social media platforms often portray stereotypical beauty ideals that are far from reality [

29,

30,

31]. As a result, individuals are continuously exposed to unrealistic body models, as online content is frequently edited and enhanced using various apps and tools. This highlights the detrimental effects of social media on young individuals’ body image perceptions and underscores the need for further exploration and awareness in this area. The appearance models conveyed by social networks are difficult to achieve [

32,

33] because the contents posted online are often carefully selected or modified using beauty filters to maximise attractive self-presentations [

34,

35]. Failing to meet these idealised standards can lead to feelings of body dissatisfaction, especially during childhood.

Most children exposed to these models do not feel up to par, which entails a gap between their perceived and ideal physical selves. This is associated with body concerns, such as an overweight preoccupation [

36] or body image avoidance [

37] and a conflict between the real and digital bodies. The appearance comparison processes that take place via social media and the constant engagement and exposure to content promoting specific societal appearance standards induce individuals to have an excessive investment in their virtual body and social reputation, so much so that they cannot differentiate the “real body” from the “virtual body” [

38]. This dualism can exacerbate issues related to the negative body and reinforce societal norms related to beauty, race, gender, and body type, potentially harming those who do not fit within those norms.

This process profoundly impacts body image during childhood, highlighting the importance of understanding and addressing the consequences of media internalisation on individuals’ well-being and self-perception during childhood.

1.2. Nurturing Body Literacy

To mitigate the negative impact of social media on children and youth, it is crucial to prioritise early reinforcement and enhancement of their ability to resist negative external influences that could hinder healthy body image development. There is a need to define a proactive approach to equip young individuals with the knowledge, skills, and resilience necessary to navigate the digital landscape and cultivate a positive body image [

39]. More generally, promoting a body-positive culture and a better understanding of the embodied existence that characterises individuals is needed.

The educational institution serves as the optimal environment for equipping individuals with the essential skills to navigate virtual reality. Furthermore, it provides a fitting context for assisting individuals in navigating the intricate journey of developing a body image, which is now intricately intertwined with the virtual reality landscape [

5,

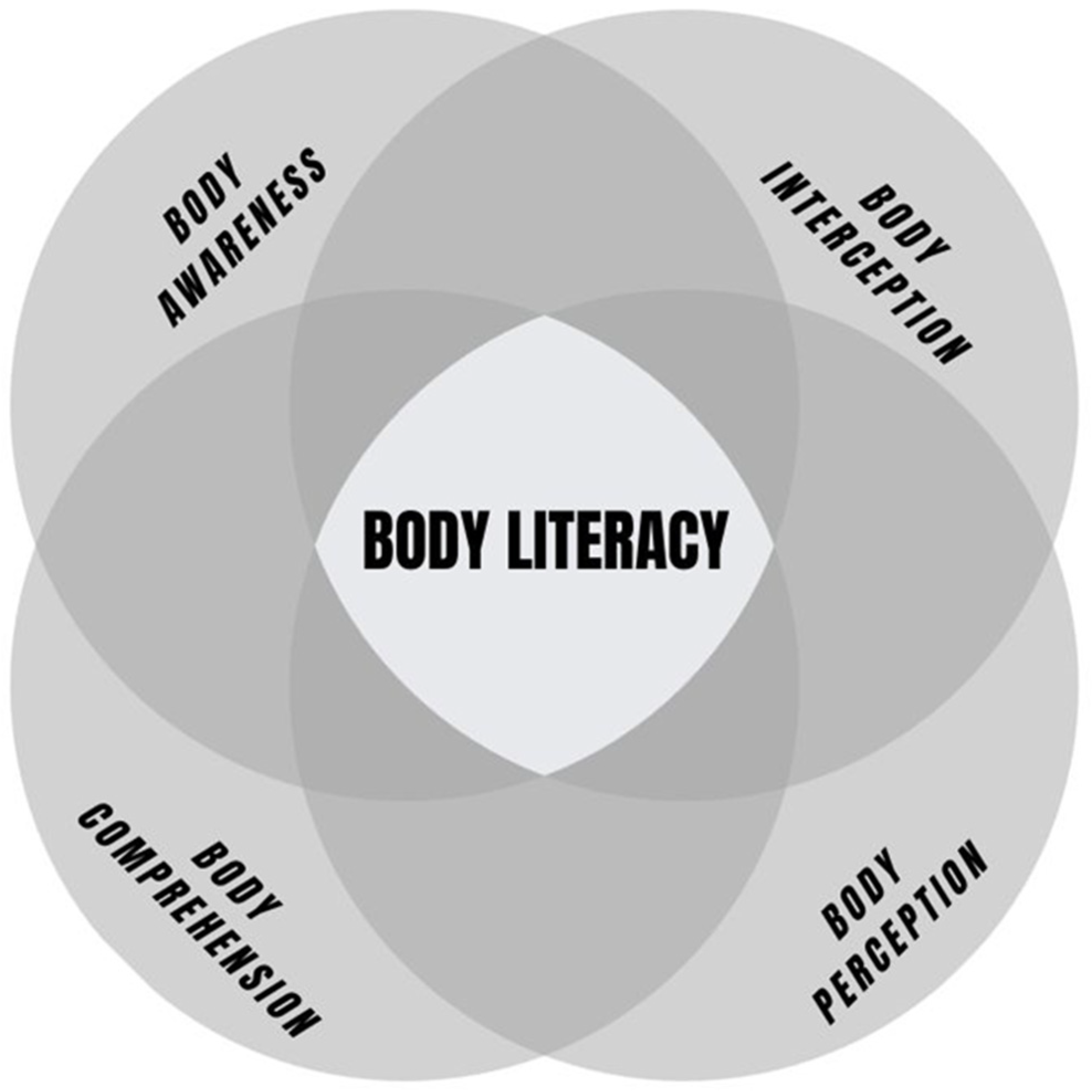

8]. Lastly, the school setting presents a unique opportunity to cultivate what we term “body literacy”—a holistic proficiency encompassing diverse facets, such as body awareness, interception, perception, and comprehension [

5] (the proposed model is represented in

Figure 1).

These key components can be described as follows: body awareness refers to the capacity to perceive and comprehend one’s own body in relation to the surrounding space, others, and the environment; body interception entails recognising and interpreting internal bodily sensations, emotions, and thoughts, thereby fostering an understanding of one’s body from within; body perception encompasses the subjective perception and evaluation of one’s own body, considering various factors, including socio-cultural elements such as culture, personal experiences, and the social environment; body comprehension pertains to the knowledge individuals possess about their bodies, including understanding how the body functions, how to maintain its well-being, and how to make informed and healthy choices regarding their bodies [

40].

Gender disparities play a crucial role in body image development, often influenced by the societal appearance ideals depicted in mass media. Therefore, it is imperative to acknowledge and consider these differences. Men may experience body dissatisfaction due to a perceived lack of muscle, while women often face pressure related to perceived excess weight. These differences reflect media messages emphasising a thin ideal for women and a V-shaped figure for men. Despite variations in male and female body ideals, excessive preoccupation with and internalisation of these standards contribute to body dissatisfaction among both genders. This dissatisfaction affects behaviours, self-esteem, mental well-being, and quality of life.

Emotional literacy is another aspect to consider. It encompasses emotional intelligence and emotion regulation, two key elements that are vital to positive body image. Emotional regulation refers to the processes of evaluating, monitoring, maintaining, and modifying emotional experiences. Emotional intelligence, on the other hand, involves perceiving, appraising, expressing, and regulating emotions effectively. Higher emotional intelligence is associated with positive attitudes, successful relationships, adaptability, and subjective physical health. Conversely, low emotional intelligence predicts body dissatisfaction and eating disorder symptoms among preadolescents and adolescents.

2. An Exploratory Research Intervention

The proposed study aimed to initiate an exploratory qualitative analysis of the suggested body literacy model, examining its connection with the attempt to understand the influence of social media on children and define strategies of intervention. Our primary goal was to examine the influence of social media usage on children’s body image development while also evaluating the effectiveness of an educational intervention to promote their body literacy. The overall scope was to inform teachers with evidence-based information and strategies to help them improve their educational approaches and equip educators with evidence-based insights and strategies, empowering them to enhance their pedagogical methodologies.

To this purpose, a sample of 50 children aged 9–10 attending a primary school in the city of Cassino (Italy) was recruited using convenience sampling. The decision to use convenience sampling was based on practical considerations of accessibility and feasibility in recruiting participants within the given time and resource constraints. While convenience sampling may limit the generalizability of the findings to a broader population, it allowed for efficient data collection. It also facilitated the exploration of the specific research objectives related to the impact of social media on children’s body image development and the effectiveness of the educational intervention [

41]. Children were recruited in collaboration with the schoolteachers, who offered their support for correctly implementing the selection process. Teachers also provided insights and guidance regarding the participants’ well-being and potential sensitivities related to body image issues. This collaboration also ensured the ethical and appropriate implementation of the study. The selection process considered children’s accessibility and willingness to participate and specific inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure a representative sample. The inclusion criteria focused on children who were actively engaged with social media platforms, considering the prevalence of social media usage among children in this age group, as indicated by previous studies [

41]. Moreover, conscious efforts were made to maintain a gender-balanced representation within the sample.

The study employed a qualitative research-intervention design to investigate the impact of an educational intervention on children’s body image development. It consisted of three phases: focus group discussions, educational intervention implementation, and post-intervention assessment. It was justified to utilise a qualitative technique to examine how social media affects kids’ body image since it allows for exploring individual experiences, perceptions, and meanings within a particular setting. The strategy used aimed to give a thorough grasp of children’s actual experiences and enable the investigation of intricate social phenomena [

42,

43]. Using a qualitative method made it possible to record the subtleties, emotions, and viewpoints. It also made it possible to investigate the larger social, cultural, and environmental aspects influencing how children use social media and view their bodies.

A comprehensive exploration of the research questions was undertaken by facilitating five distinct focus group discussions meticulously conducted within a rigorously controlled environment. Employing a semi-structured interview guide, participants were provided with a systematic framework to engage in multifaceted dialogues. These dialogues, characterised by their dynamic and interactive nature, facilitated the articulation of participants’ nuanced opinions, experiential narratives, and apprehensions regarding their interactions with social media platforms. The deliberate use of a semi-structured approach within the focus group discussions served as an invaluable tool. It not only fostered an atmosphere conducive to the unfolding of diverse viewpoints but also allowed for exploring participants’ cognitive processes, emotional resonances, and reflections. This methodological design thus facilitated a profound comprehension of the intricate ways in which social media influences the development of children’s body image. The controlled setting of the focus group discussions further ensured a consistent and controlled context, enabling a comparative analysis of participants’ responses across the various sessions. This analytical rigour, inherent in the structured methodology, aimed to uncover overarching trends, idiosyncratic narratives, and patterns that may shed light on the broader research objectives.

Following the focus group discussions, an educational intervention was designed to enhance children’s body literacy. The intervention was intricately crafted to foster the development of specific aspects of bodily consciousness, including body awareness, interception, perception, and comprehension. To cater to the age-specific requirements of the participants, a series of seven sessions were implemented, each extending over approximately three hours, resulting in a total duration of 21 activities. Each session followed a well-thought-out plan that incorporated various teaching methods, such as educational presentations, interactive exercises, group discussions, and hands-on activities. The educational presentations aimed to convey theoretical knowledge about concepts related to body image. Interactive exercises were strategically included to actively involve the children in kinaesthetic learning, establishing a direct link between theoretical knowledge and practical application. Group discussions provided a platform for collaborative learning, enabling participants to share their perspectives and collectively deepen their understanding. Additionally, hands-on activities were carefully integrated to enhance the experiential dimension of the intervention. These activities were designed to be tactile and participatory, encouraging a holistic engagement with the subject matter. The overarching objective was to create a dynamic and immersive learning environment that not only conveyed theoretical concepts but also allowed the children to actively experience and internalize the content. The iterative structure of the sessions, spanning multiple hours throughout the intervention, provided ample time for reinforcement, reflection, and assimilation of the acquired knowledge. The cumulative arrangement of the activities facilitated a thorough exploration of body-related concepts, ensuring a nuanced and enriched educational experience for the participants. The intervention content was developed based on theoretical frameworks and evidence from previous studies on body image development and educational interventions targeting children [

44]. The content was adapted to the specific needs and concerns identified during the focus group discussions. Specifically, within the conceptual framework of this study, the content encompassed a multifaceted construct comprising several dimensions, including self-awareness, positive body development, gender differences, emotional literacy, body dysmorphic disorder, and body acceptance. After the completion of the educational intervention, a follow-up focus group discussion (

n = 5) was conducted to assess the impact of the intervention on their body literacy development and awareness. The same inclusion criteria and age range were applied to selecting participants. After the intervention, the post-intervention focus group discussions explored changes in children’s body image perceptions, attitudes, and knowledge. Likewise, in Phase 1, the discussions were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim for analysis.

The qualitative methodology employed in this study adhered to Tuffour’s approach [

45], providing a robust framework for conducting thematic analysis. Thematic analysis was selected as the methodological tool to scrutinise and interpret the data collected through focus group discussions [

46]. This analytical approach aligns with the inductive nature of qualitative research, allowing for the exploration of patterns, themes, and meanings inherent in the rich and nuanced responses of the participants. The thematic analysis involves a systematic process of coding and categorisation, enabling the extraction of key insights and the identification of recurring themes within the dataset. Adopting this methodological framework ensures a rigorous and systematic examination of qualitative data, contributing to a deeper understanding of the participants’ perspectives and facilitating the extraction of valuable insights relevant to the study objectives. The iterative nature of thematic analysis permits the identification of patterns and nuances, allowing for a comprehensive exploration of the complex interplay of factors within the data. This methodological approach, grounded in Tuffour’s framework, strengthens the scientific rigour of the study, enhancing the validity and reliability of the findings derived from the qualitative analysis. This data collection method allows the researchers to have the flexibility of a guided exploration of the topic and to ask the participant to expand on what is said [

43]. NVivo was employed to speed up the data analysis process [

47]. The robust platform provided by NVivo for managing, organising, and analysing the qualitative data increased the effectiveness and precision of the theme analysis. The programme allowed for the systematic coding and categorisation of the transcribed data, enabling the discovery and study of important themes and ideas about the effects of social media on young people’s body image development.

3. Key Findings from the Exploratory Study: Use and Habits in the Digital Era

The thematic analysis of the data revealed several key themes related to the participant’s experiences and behaviours. Our study encompassed a wide range of themes, each providing valuable insights into various aspects of social media engagement:

Photo and video sharing: Participants shared their habits and preferences regarding sharing photos and videos on social media platforms.

Parental awareness: This theme investigated the degree of parental awareness and involvement in their children’s social media activities.

Perceived negative consequences: Participants expressed concerns and fears regarding potential negative outcomes associated with social media use, including cyberbullying and privacy issues.

Age disclosure: This theme focused on whether participants disclosed or concealed their real age on social media platforms.

Judgment of influencers and peers: Participants articulated their opinions and attitudes toward popular social media influencers and the activities of their peers on these platforms.

Judgment of adults: This aspect explored participants’ perceptions and judgments of adults’ utilisation of social media.

Self-perception: Our study delved into participants’ self-perception concerning their online presence and how social media affected their self-image.

Ownership of mobile phones: We examined participants’ ownership of mobile phones.

Time and mode of mobile device usage: This theme encompassed the time participants spent on mobile devices and their specific activities.

Use of filters: Participants discussed their use of filters to enhance their appearance in photos and videos on social media platforms.

Parents and family members: Our investigation extended to participants’ interactions and relationships with their parents and other family members on social media.

Use of social media: This theme provided insights into participants’ overall engagement with and usage of various social media platforms.

The themes identified in this study have been systematically organised into the categories presented in

Table 1. These categories serve as insightful lenses through which to examine participants’ experiences and behaviours pertaining to photo and video sharing, parental involvement, perceived consequences, self-perception, and their utilisation of mobile phones (or other devices) and social media platforms. Within

Table 1, essential quotes have been meticulously documented, providing a concise yet comprehensive overview of the thematic landscape. Featuring key quotes serves as a succinct representation of the identified categories and is a valuable resource for researchers and educators seeking a comprehensive grasp of the qualitative findings. The iterative and systematic nature of the thematic analysis, anchored in Tuffour’s approach, enhances the scientific rigour of the study, contributing to the validity and reliability of the insights gleaned from participants’ experiences. This methodological approach establishes a robust foundation for translating qualitative findings into practical applications for educational interventions, ultimately enriching the scholarly discourse on the complex interplay of factors in the realm of photo and video sharing, parental involvement, perceived consequences, self-perception, and technology usage.

Personal mobile devices are prevalent among the participants, with most owning their mobile phones. However, a few children (n = 4) mentioned not having personal mobile devices but being allowed to use their parents’ phones. It is worth noting that one child did not participate in the discussion due to not having his mobile phone, which made him feel embarrassed. Broadly, they are avid users, primarily engaging with popular apps, such as TikTok, Telegram, YouTube, and Twitch. Telegram is commonly used for messaging, WhatsApp for texting and sharing pictures with classmates, and YouTube for uploading videos (one child reported having his channel). At the same time, Discord, Twitter, Instagram, TikTok, Twitch, Roblox, and Snapchat are also popular among the participants. Notably, none of the participants reported using Facebook, as they perceived it as a platform for older individuals or because they preferred not to connect with their relatives on that platform.

When it comes to sharing pictures about their body image, varied opinions were observed, particularly among girls. Some girls (

n = 7) agreed with their parents posting their pictures only if they were satisfied with their appearance, while others mentioned enjoying being photographed and posted when they felt they looked good. Interestingly, three girls in the group were deemed “influencers” due to their ability to share captivating photos and videos, underscoring the importance of projecting an attractive image and adhering to societal beauty standards [

48]. This observation underscores the importance placed on physical appearance among children, particularly in the context of sharing pictures on social networks [

49]. Focusing on specific girls’ influence inside the group raises the possibility that social dynamics and peer acceptance influence young children’s views of attractiveness and their desire to fit in [

50]. Recent studies show that young children are greatly influenced by their classmates regarding looks and social acceptance, especially throughout their preadolescent years [

51]. Children’s self-esteem and body image can be greatly affected by the desire to be seen as attractive and to adhere to conventional beauty expectations [

52].

Moreover, it was evident that many girls habitually capture multiple photographs, carefully selecting the most attractive ones for sharing. This behaviour aligns with findings from recent literature in this field [

30,

53]. Notably, a sizable portion of participants—boys and girls alike—consciously withhold from sharing their pictures or films, either out of personal preference or due to parental restrictions [

24,

54].

Participants expressed their worries about coming across Internet haters, noting prior instances of being the target of insults and vitriol. These concerns reflect the potential detrimental influences of cyberbullying on young individuals’ behaviours. Not surprisingly, research studies have consistently demonstrated the prevalence and negative consequences of cyberbullying among children and adolescents [

55]. The experience of being subjected to insults and negative comments online can significantly contribute to feelings of self-consciousness, social anxiety, and body dissatisfaction [

51]. In this light, excessive social media usage was strongly opposed by one girl, who highlighted how it could foster negativity and hostility. On the contrary, some boys mentioned that they would only consider sharing their pictures or videos if they could monetise their content, even with strangers.

Beauty filters emerged as a common practice among the participants to enhance their body satisfaction. Recent research has highlighted the growing prevalence of filter use and image alteration among preadolescents [

50]. The data collected demonstrated that this behaviour starts early, even during primary school, as children become acquainted with these practices. Many children expressed dissatisfaction with their appearance in pictures and their reluctance to be posted on social networks. They found that using beauty filters made them feel better about themselves and often used them when sharing photos, modifying their appearance according to the filters. Interestingly, some girls mentioned refraining from using beauty filters because they felt they became less attractive once the filters were removed. They embraced their natural selves and only used funny filters when interacting with their siblings.

Using beauty filters to enhance their appearance and feel better about themselves further emphasises the influence of societal beauty standards on children’s body image. Beauty filters alter facial features, smooth out imperfections, and enhance certain aspects of one’s appearance. In many circumstances, children’s use of beauty filters is an attempt to conform to the idealised standards of beauty promoted by social media platforms and society at large. This underlying motivation was revealed, in particular, when children explained their use of filters to respond to the influence of “others”. Children expressed a need to use filters to enhance their appearance. They indicated they felt compelled to conform to the beauty standards they encountered on social media. Broadly, the reluctance to post unfiltered photos and the preference for using beauty filters when sharing pictures could indicate a desire to present an idealised version of themselves to others. Using beauty filters and the pursuit of conforming to idealised beauty standards on social media can lead to problems with body image among children. This can result in unrealistic standards, negative self-perception, emotional distress, disordered eating, and a detrimental impact on self-worth. Therefore, from an educational perspective, it becomes imperative to tackle these concerns by promoting self-acceptance and media literacy and cultivating positive self-esteem founded on individual qualities that extend beyond mere physical appearance.

Regarding parents’ awareness of their children’s social network activities, the data revealed diverse experiences among the participants. Some children stated that their parents needed to be made aware of their social media presence, indicating a lack of parental monitoring or limited communication about online activities. This finding aligns with previous research highlighting parents’ challenges in keeping track of their children’s digital behaviour [

56,

57]. In contrast, other children took active measures to prevent their family members from seeing their posts by blocking them. This behaviour may reflect a desire for privacy and autonomy in online spaces as children navigate their developing identities. Studies have highlighted the role of privacy concerns and the need for online personal space among adolescents [

58].

Interestingly, the participants displayed different approaches to seeking permission from their parents to use social media. While most of the children sought permission, some did not (

n = 6), suggesting varying degrees of parental involvement or permissiveness about social media use. Additionally, a subset of participants resorted to using pseudonyms or adjusting their age to create private accounts, potentially to maintain a sense of anonymity and control over their online presence. It is also expedient to overcome the age limitations many providers set. These findings are consistent with research emphasising using pseudonyms and privacy settings as young individuals’ strategies to manage their online identities [

57].

Furthermore, it is notable that some cases emerged where a girl blocked her mother from seeing her pictures, but her mother still published them against her wishes. This finding highlights a potential breach of trust and conflicts around consent within the parent–child relationship in the context of social media use. Further research could explore the dynamics and consequences of such instances to understand better the complexities of parent–child interactions and the negotiation of boundaries in the digital realm.

4. Discussions: What We Have Learned with a Focus on Body Image

As stated, the primary objective of this study was to examine the potential influence of early social media use on children (9–10 years), with a specific emphasis on its impact on their perceived body image and the broader process of body formation. By examining the correlation between children’s social media usage and body image, the study aspired to enhance our comprehension of the intricate factors influencing children’s perceptions and body-related experiences. Inextricably linked to this objective, it also sought to offer a better understanding of the intricate interplay between real-life and virtual existence and the resulting implications for educational strategies. In connection to this, the study, with the more applicative part, sought to promote a body-positive culture and a better understanding of the embodied existence that characterises individuals.

The obtained results contribute to extending the existing scientific evidence regarding the correlation between social media usage and body image concerns among children [

58,

59,

60]. This finding holds particular significance in an educational context. Notably, while preadolescents and adolescents are conventionally deemed the most susceptible age group to social influences during the identity formation process, it is imperative to acknowledge that the influence of social media on body image development initiates even earlier, during childhood. Childhood represents a critical phase in the developmental process of body image, as it encompasses significant changes in body, self-concept, mood, and social interactions. During this period, children are susceptible to internalising societal beauty ideals and comparing themselves to others, which can be amplified by exposure to social media [

61,

62].

In broad terms, children are growing aware of the potential risks associated with social media usage. However, a greater perception of its negative effects on body image development is still needed. This aspect still needs to be considered and warrants further attention and consideration. While some individuals may recognise the general risks associated with social media, they may not fully grasp its specific implications on shaping body image perceptions, particularly among children. Some children interviewed showed a certain understanding of the phenomenon, asking themselves doubts and questions regarding the risks; on the other hand, other children seemed more unaware of the risks, recognising only the playful and entertainment component of social media. Thus, there is still a need for greater understanding and acknowledgement of the extent to which social media influences body image development. Above all, there is a compelling educational imperative to assist children in cultivating a nuanced understanding of the intricate social dynamics that unfold within the virtual realm. This knowledge is essential for equipping them with the skills to navigate and engage responsibly in the digital environment, ultimately fostering their digital literacy and personal development.

The early use of social media has significant implications for developing and maintaining a positive body image in children, yet these effects often go unnoticed. Children heavily engaged in virtual realms struggle to differentiate between their natural bodies and the various idealised virtual bodies they encounter, leading to what is commonly referred to as the dualism between the real body and the virtual body [

30]. The constant exposure to stereotypical body ideals presented through social media platforms contributes to internalising these standards as the reference for body image. This internalisation perpetuates the divide between one’s physical reality and virtual representation, presenting a pronounced risk factor for developing body dissatisfaction. The immersive nature of social media platforms and the proliferation of carefully curated and idealised body representations create an environment where children constantly compare themselves to unrealistic beauty standards. These constant social comparisons and the pressure to conform to digitally altered and filtered images can erode children’s self-esteem and foster negative body image perceptions.

To address this issue, it is crucial to raise awareness among children, parents, educators, and policymakers about the potential impact of social media on body image development. Addressing these issues through comprehensive educational initiatives and awareness campaigns that promote a healthier and more realistic perspective on body and body image in the digital age is imperative. Prohibiting young people from social media is not the most effective strategy for mitigating its adverse effects. Instead, fostering media literacy and cultivating critical thinking skills can empower children to navigate the digital realm and cultivate a more grounded perspective on body diversity and acceptance, as advocated by Holland and Tiggemann [

63]. Additionally, it is imperative to enhance real-life experiences. Encouraging participation in positive offline activities, championing self-compassion, and nurturing supportive relationships all play pivotal roles in offsetting the adverse impacts of social media on body image.

The proposed intervention for the children was explicitly designed to foster body awareness, interception, perception, and comprehension. Age-appropriate educational activities and interactive sessions were strategically employed to reinforce this objective, with a specific focus on what was previously described as body literacy. Body literacy was considered a protective factor to reduce the negative effects of social media use. The thematic analysis of the post-intervention focus group underscored a notable enhancement in the children’s ability to recognise and discern the impact of social media on their body awareness, interception, perception, and comprehension. Moreover, the children increased their awareness of the interplay between their real lives and virtual personas. They also displayed a heightened inclination toward better caring for their bodies, recognising it as a pivotal element for their overall well-being.

Furthermore, the intervention engendered noteworthy enhancements in media literacy. Children were equipped with the competence to critically evaluate the veracity and potential ramifications of the content they encountered within social media environments. This newfound discernment facilitated their ability to differentiate between authentic information and potentially misleading or deleterious material. Equally significant were the observed improvements in self-image, as children exhibited greater self-assuredness in embracing their individuality, manifesting reduced proclivities for unfavourable self-comparisons vis-à-vis idealised online representations.

Additionally, an upswing in emotional resilience was manifested, rendering the children better equipped to navigate adversarial comments and peer pressures concerning body image. This transformation in outlook contributed to heightened self-esteem. Manifestations of this transformation were also noted in health-related behaviour, with several participants adopting healthier dietary choices and augmenting physical activity levels, acknowledging the intrinsic relationship between such habits and overall well-being.

The progression of “body literacy” appears consistent with this approach. By providing children with vital skills and knowledge, they can be empowered to nurture a positive body image and develop the capacity to forge a harmonious sense of identity that effectively bridges the gap between the real and virtual worlds. Body literacy is a comprehensive understanding and awareness of one’s body, encompassing physical, emotional, and social aspects. It is essential for children for several reasons.

The evolution of body literacy aligns seamlessly with this approach, emphasising the importance of equipping children with essential skills and knowledge that empower them to cultivate a positive body image. This holistic perspective fosters a healthy relationship with their physical selves. It enables the development of a well-rounded and harmonious sense of identity that effectively navigates the complexities of both the real and virtual worlds. Body literacy, in essence, signifies a comprehensive understanding and heightened awareness of one’s own body, encompassing physical, emotional, and social dimensions. This multifaceted awareness is particularly crucial for children for several compelling reasons. Firstly, it lays the foundation for a positive body image, instilling a sense of self-acceptance and appreciation for the diversity of body shapes and sizes. Moreover, by nurturing emotional intelligence in relation to their bodies, children can better navigate the emotional challenges associated with self-perception, peer dynamics, and societal expectations.

Body literacy equips children with the tools to make informed and healthy choices regarding their bodies. This includes understanding the impact of nutrition, physical activity, and overall well-being on their development. Children are better prepared to make choices, contributing to their overall health and resilience by fostering a sense of agency and autonomy over their bodies. In addition, body literacy becomes a crucial component in navigating the social aspects of self-presentation and interaction in an increasingly digital and interconnected world. Children are exposed to diverse representations of bodies through various media, including social platforms. Body literacy empowers them to critically evaluate and contextualise these images, fostering a resilient mindset that goes beyond superficial standards and encourages authentic self-expression.

Body literacy serves as a catalyst for the evolution of what can be termed “Onlife education”—an educational paradigm adept at seamlessly merging the virtual and tangible realms within a holistic framework. This innovative approach facilitates children’s growth and development within a hybrid societal context and imparts profound insights into the functioning of the human body and its requisites for maintaining health. Consequently, children are empowered to make informed choices that proactively contribute to their overall well-being.

In addition, by focusing on body literacy, educators can empower children to cultivate a healthy body image by adopting an educational approach rooted in body literacy. This involves guiding them in the art of valuing their bodies, irrespective of their size, shape, or outward appearance. Such an approach can significantly diminish the likelihood of body dissatisfaction, the onset of eating disorders, and the erosion of self-esteem, as demonstrated by Halliwell et al. in their study [

44]. Furthermore, this body-oriented approach can equip children to recognise early signs of health issues and take proactive steps towards seeking appropriate care. This knowledge becomes particularly invaluable in preventing and managing conditions like obesity, diabetes, and various mental health disorders, as underscored by Greenberg et al. in their research findings [

64].

Emotions are, finally, an important aspect that can be tackled. As part of the interventions encompassed in body literacy, educators can teach children how emotions can manifest physically and manage their emotional well-being through techniques like mindfulness and stress management [

65]. Educators can also contribute to teaching children about personal boundaries, consent, and understanding their own and others’ physical and emotional boundaries. This knowledge is crucial for developing positive and valuable personal relationships [

66].

5. Body Literacy: A Way Forward

The exploratory study has provided initial insights into the effectiveness of body literacy. This opens two distinct avenues for further exploration. Firstly, there is a need to delve deeper into this complex concept, analysing it rigorously to gain a more comprehensive understanding of its effectiveness and consistency. Secondly, there is a requirement to engage in a discourse regarding its potential practical application.

In relation to the last issue, the school environment emerges as the ideal setting for promoting body literacy among these conditions. In pursuit of this goal, several interventions are deemed essential. First and foremost, integrating body literacy into the school curriculum is a fundamental step. This integration should be thoughtfully structured to establish meaningful connections with biology, physical education, health education, and psychology. This interdisciplinary approach can provide students with a comprehensive understanding of their bodies and the emotional aspects associated with them. Equally vital is establishing a safe and inclusive learning environment within schools. Creating a space where students can openly discuss their bodies, emotions, and questions without apprehension of judgment or discrimination is essential. Such an environment fosters candid conversations and allows students to explore and express their thoughts and concerns about body image.

Moreover, the preparation of educators is paramount. Teachers should undergo specialised training to equip themselves with the necessary skills and knowledge to convey body literacy principles to their students effectively. These educators are pivotal in shaping students’ perceptions, attitudes, and behaviours concerning their bodies.

Lastly, a holistic approach to body literacy initiatives must include the active engagement of parents and the broader community. Collaboration with parents and community organisations ensures that the principles of body literacy are reinforced beyond the classroom setting. This collective effort strengthens the message and provides a consistent and supportive network for children’s development.

6. Conclusions

By investigating the impact of social media use on children’s body image development and implementing and testing an educational intervention targeting body literacy enhancement, we aimed to shed light on the potential effects of social media on body image and propose strategies to foster a more positive and informed relationship between children and their bodies. The implications of this research intervention extend beyond the realm of academia. By revealing the nuanced effects of social media on body image and proposing targeted strategies for nurturing body literacy, the overall scope is to provide educators, parents, and guardians with actionable insights. This information equips them to guide children towards a more resilient and positive relationship with their bodies in an age dominated by virtual influences.

Social media have become a ubiquitous presence in the lives of children, immersing them in a realm filled with unrealistic beauty standards against which they continually measure themselves. There is a clear need for heightened adult oversight and guidance, encompassing both the duration of exposure and the nature of the content consumed. However, it is important to note that there are more effective strategies to mitigate the adverse impacts of its use than simply restricting access to social media. To cultivate and sustain a positive body image, it is imperative to develop body literacy from the earliest stages of a child’s life to equip children with the skills necessary to navigate the complex landscape of body image in the digital age, ultimately bolstering their overall well-being.

The proposed concept of body literacy emerges as a promising and pivotal realm for research and intervention. Its application carries profound implications for the holistic development of children, encompassing both their physical and emotional well-being. In this context, educational institutions and educators are pivotal in disseminating this knowledge. By nurturing a comprehensive understanding of their bodies, children are empowered to make discerning choices that transcend health, relationships, and overall well-being. This lays the cornerstone for a future marked by enhanced health and a more enriched life experience across the real and the virtual domains.

Given the exploratory nature of this study, future research endeavours should delve more deeply into two critical areas. Firstly, it is pertinent to conduct extensive investigations into the effects of social media on the development of body image in children, allowing for a more comprehensive understanding of the dynamics at play in this context. Secondly, there is a need to advance and refine the concept of body literacy, culminating in constructing a robust theoretical reference model that can be applied across diverse contexts. Such endeavours will undoubtedly contribute to the body of knowledge in this field and pave the way for more effective interventions and support systems for children navigating the complexities of body image in today’s digital landscape.