Abstract

The study was focused on understanding emotional and spiritual intelligence, and leadership linkages. The aim of the study was to explore the relationship between emotional and spiritual intelligence and self-leadership skills of university students in the fields of management, as potential future leaders. The data were collected using three scales: Emotional Intelligence Scale (WLEIS), Spiritual Intelligence Inventory (SISRI-24), and Self-Leadership questionnaire. The study was conducted among 190 university students. The results obtained show that there are connections between emotional and spiritual intelligence and self-leadership. The study may be a good starting point for further research in this field and lead to reflection about spiritual knowledge on the leadership education program.

1. Introduction

Leadership education programs in universities have traditionally focused on such competencies as management and economics [1] in order to prepare good managers for organizations. It was related with the belief that only a leader with high intelligent quotient (IQ) can better understand and optimize organizational systems and their complexities. Many previous studies in the leadership literature have focused on the rational intelligence of leaders. The IQ for assessing human intelligence is commonly accepted as a ratio of rational and logical knowledge [1] that allow leaders to gain success. However, many employees who want to be leaders are eventually eliminated, despite their high logical intelligence [1]; and highly intelligent leaders are not necessarily more effective [2]. As a result of the further search for what makes a leader effective, attention was paid to emotional intelligence (EI), that was an important challenge for future leaders [3]. EI tried to explain why some employees are better as leaders than the others [4]. Some research has pointed out that feelings are the most crucial factor for leaders [5] and leaders and followers should possess rather emotional knowledge than technical knowledge [6]. Another research has indicated the link between EI and the performance of leadership [7,8]. Thus, teaching managers to build better relationships was crucial to the propagation of organizational performance systems [1]. Leadership education programs have focused on emotional intelligence as desired knowledge. However, in today’s ever-changing business environment, there is a need for something more. After a period of fascination with the IQ and EI of a leader, the time has come for a new kind of intelligence. Beyond the awareness of intellect and relationship, the ability to find inner security in that external environment is a key for effective leadership. The term “spiritual intelligence” (SI) has appeared [9], and is considered as the foundation of both rational and emotional intelligence [10] (p. 57). In response to the need to meet the challenges of unpredictable circumstances, spiritual knowledge should be included in leadership training [1].

The IQ responses on how to lead; the EI—who you lead; and the SI—why you lead [1]. These questions can be starting points for leadership education development, because all three intelligences: IQ, EI and SI, make up leadership intelligence [2]. This is important because of a limited number of research-linking intelligence, leadership and education [11]. Leadership education needs to be guided by a strong, up-to-date curriculum and cutting-edge knowledge, which provides the crucial leadership skills and competencies that students need to develop and sustain as future leaders. Although management is related to logical intelligence, decision making is based on beliefs and values as a guideline; this means spiritual knowledge [12,13,14]. Making managerial decision based only on cogent intelligence and reducing emotional and spiritual side of employees is ‘a mistake’ [12]. Modern leadership education should also include emotional and spiritual intelligence.

This study was focused on both emotional (EI) and spiritual intelligence (SI). Firstly, the study examined the level of EI and SI of university students in the field of management. This enabled the study to determine the needs for leadership education programs in the topics. Secondly, the study explored the correlation between the constructs: emotional intelligence, spiritual intelligence and self-leadership. Thirdly, it offered a study of the correlation between the subscales of these constructs.

This paper is structured as follows. The first section describes emotional and spiritual intelligence on leadership. Hypotheses of the field study were then developed under this section. The next section describes the methods and the data analysis that were used to support the field study. The remaining part of the paper concludes the findings, with directions for further research for leadership development in education.

2. Emotional and Spiritual Intelligence on Leadership

2.1. Emotional Intelligence of a Leader

The theory of emotional intelligence (EI) was popularized and linked to leadership by Daniel Goleman [7,15], and since that time, it has been considered as the most significant skill, necessary competency and proper behaviour of a leader [16]. EI is labelled as the awareness, assessment, and management of one’s own emotions, as well as others’ emotions [17,18,19,20]. Over the years, several EI models were proposed, to broaden knowledge about the abilities, personalities, and skills related to emotional side of man [21,22]. The commonly used metrics of emotional intelligence indicate four dimensions: appraisal of self-emotion, appraisal of others’ emotion, use of emotion, and regulation of emotion, according to Emotional Intelligence Scale WLEIS [23]. The self-emotion appraisal dimension is related to the capability to recognize and express one’s own emotions. The appraisal of others’ emotion is related to the ability to observe and distinguish the emotions of other people. The use of emotion focuses on the skill to use emotions constructively. The regulation of emotion means regulating one’s own emotions and managing one’s own emotional experiences. This model was used in this study.

In the context of leadership, managers should not only identify the emotional states of their employees, but also regulate them [24]. Some research presents positive links between leaders with high EI and the happiness, satisfaction, mindfulness, trust, faith and commitment of workers [25,26,27]. It is related to a leader’s ability to better understand their employees and adjust their leadership conduct suitably [28]. However, EI is not the only determinant of employee well-being, but has a profound impact on leadership effectiveness and success [29,30,31]. The managing of EI has a strong impact on success [32]. Many researchers have also stated that leaders with high EI influence organizational results [33], the functioning of a group and a team [32,34]; organizational change [35,36]; potential sustainable growth [37]. Many researchers’ studies also included the relationship among emotional knowledge and leadership styles, like transformational or visionary leadership [38,39]. To summarize, the hypothesis is as follows:

Hypothesis 1:

Emotional intelligence has a positive relationship with self-leadership.

2.2. Spiritual Intelligence of a Leader

Spiritual intelligence connects intelligence with spirituality as a new construct [10], and as a quotient of the level of spiritual leadership [40]. While spirituality is a sense of higher-consciousness and divine existence [10], spiritual intelligence is related to the skills to use divine aspects to enable goals achieving and problems solving [41] (p. 59). Spiritual intelligence is an internal ability, related to mind and spirit and its connections to the world [42]. However, this internal ability influences external ability. Thanks to spiritual intelligence, we can discover a deeper sense and use it to solve the complex problems of the present. Spiritual intelligence can develop a constructive trait and enable one to make use of the capability to face danger and anger. People with a high spiritual intelligence rate are more tolerant, honest, and full of affection to others in their life [43]. Spiritual intelligence allows us to also draw knowledge from the richness of our heart and the universe. Many authors have reported that it is a kind of intelligence that allows a sense of contact with people, the whole, a sense of its own fullness, seeing connections between diverse things [44]; and also understanding the significance of relationships to support the interconnections [10,45]. It is an ability to see spiritual aspects of the self and others, and interconnectedness [46]. Spiritual intelligence is an internal compass between what is internal and what is external, providing a sense of meaning and a significance to experiences of which we are the co-creators. Many authors have pointed to this sense of higher meaning and purpose [41,44,47] and critical approach to them [46]. One of the most important aspects of spiritual knowledge are questions ‘why’ or ‘what if’ to seek fundamental answers [44]. Spiritual intelligence is a self-consciousness that teaches us how to go beyond the sphere of ego closest to us and reach deeper layers of the potential hidden within us [44], for a better existence [48].

Many authors have stated the core elements of spiritual intelligence [41,48,49,50]. Although the elements of spiritual intelligence differ slightly, most of them are overlapping. The most frequently used words are ability, capacity and capabilities. Besides such capabilities as high consciousness, self-awareness, transcendence, mastery, sense of the sacred or divine, altruistic love, freedom [48,50], which may sound abstract, many other abilities can support us in everyday situations, for example, understanding and embracing everyday experiences, events, and relationships, using spirituality to solve everyday difficulties, engaging in moral behaviour, feeling a sense of meaning, trusting for oneself and others, and developing responsibility for wise behaviour [49]. It means that spiritual intelligence not only allows us to feel higher and deeper feelings in certain moments, but also helps us in our everyday personal and work life. It is very important, because we are not different at workplaces and outside our workplaces. We are the same both in our personal and our work-life situations, with a certain perspective, consciousness, self-knowledge, approach to difficult situations, solving problems or building relationships with people. Thus, what we think and do is expressed not only in our personal life but also in our workplaces. One of the concepts of spiritual intelligence includes critical thinking about existence, that is related to thinking about the spirit, the world, and the existence; personal meaning production—related to seeking a sense of meaning and purpose in the experiences of one’s life; the expansion of conscious state—related to control of getting in the higher states of awareness; transcendental consciousness—related to recognizing the ways of attending transcendence; [46]. This model was used in this study.

Spiritual intelligence is crucial for leaders, in order to create spirituality in the workplace for followers. In a dynamic business environment, leaders have to seek inner peace [51]. Spirituality is needed for leaders to grow their own sense of identity, to find the purpose of their own work, and to support follower’s values with a strong sense of meaning [52]. Spiritual leadership is based on the essential needs of people in order to gain a harmony of vision and value among individual employees and whole groups, which can increase organizational results [53]. Many studies have indicated that spiritual leadership is necessary for spirituality at all level of work: the individual, team, and organization [54,55]. It affects life and job satisfaction [56], motivation and commitment [57], organizational efficiency [58], productivity and performance excellence [59] and the flexibility and creativity of the organization [60]. Spiritual intelligence might be considered as a driving power for a leader [61]. To summarize, the hypothesis is as follows:

Hypothesis 2:

Spiritual intelligence has a positive relationship with self-leadership.

2.3. Relationship of Emotional and Spiritual Intelligence

Emotional and spiritual intelligence supports organizational principles, ethical values and all organizational decisions. However, there are only a few studies that have shown the need for all leaders to have emotional intelligence with spiritual strength and lead with more meaningful behavior, or the importance of the relationship between emotional and spiritual intelligence, and the efficiency of leaders [62]. The studies showed that emotional intelligence and spiritual intelligence are interrelated [48] and strengthen each other [63]. Spirituality growth enhances emotional awareness. This, in turn, impacts the competence of managing and controlling emotions, which further reinforces spiritual development [64]. Thus, emotional intelligence level affects one’s use of spiritual intelligence [10]. Spiritual knowledge facilitates understanding reason and emotion [23]. Many elements of both emotional and spiritual intelligence are common. Spirituality develops the intrapersonal and interpersonal competences [44] that are the components of emotional intelligence. Emotional intelligence with the understanding of emotions—both our own and of others—is closely related to such good attitudes as humility, forgiveness and thankfulness [43].

However, there is still insufficient research to show the relationship between emotional and spiritual intelligence. Moreover, many research studies are theoretical or conceptual studies and were derived from an Eastern context. Thus, this leads to the follow hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3:

Emotional intelligence has a positive relationship with spiritual intelligence.

3. Method

The study used an online questionnaire among students from Bialystok University of Technology in Poland. The data were collected in November 2019 from 190 students. The questionnaire contained three dimensions: spiritual intelligence, emotional intelligence and self-leadership. In this study, the SISRI-24 (Spiritual Intelligence Self-Report Inventory) was used [41]. The SISRI-24 questionnaire was primarily used for a sample of university students with satisfactory validity. Thus, the SISRI-24 was applied in this study to measure spiritual intelligence with its subscales: CET, TA, PMP, CES. In the SISRI-24 questionnaire, five-point scales from 0—‘not at all true’ to 4—‘completely true’ was used.

Next, the Emotional Intelligence Scale (WLEIS) proposed by Wong and Law [65] with four subscales: SE, OE, UE and RE were adopted in this study. The WLEIS also had sufficient reliability, with validation in many countries [65]. In this questionnaire, a five-point Likert scale, from 0—‘totally disagree’ to 4—‘totally agree’, was used.

In order to determine the abilities of leadership inherent in the students, the Self-Leadership questionnaire (SL), according to Houghton [66], was used with five dimensions: (LS1) self-goal setting related to set specific goals for yourself; (LS2) evaluating beliefs and assumptions related to ability to evaluate the accuracy own beliefs and articulate them; (LS3) self-observation related to awareness of own progress and keeping a track; (LS4) focusing on natural rewards related to among others seeking pleasant rather than the unpleasant aspects of own’s work; (LS5) self-cueing with using concrete reminders (e.g., notes and lists) to help focus on activities. In this questionnaire, a five-point Likert scale from 0—‘totally disagree’ to 4—‘totally agree’ was also used.

The SISRI-24, WLEIS and Self-Leadership questionnaires were used in the Polish language.

3.1. Data Analyses

Descriptive statistics, reliability and validity were calculated for the SISRI-24, the WLEIS and the Self-Leadership questionnaire and the subscales. The Cronbach’s alpha estimated the internal consistency of each priori scale and subscale. Pearson correlations between the SISRI-24 total and the subscales: CET, TA, PMP, CES; and the WLEIS total and the subscales: SE, OE, UE, RE; and the Self-Leadership questionnaire and the subscales: LS1, LS2, LS3, LS4, LS5. The confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed using structural equation modelling (SEM) with the STATISTICA program.

3.2. Participants

The study was conducted among 190 students from Faculty of Engineering Management at the Bialystok University of Technology in Poland. The students are educating themselves to become managers in the near future, thus they are potential future leaders. The survey allowed one to gather the information on the field of study, gender and years. Sixty-six percent (66%) of the respondents were female and thirty-four percent (34%) male; the students were from 18 to 24 years old; and all respondents study on different kinds of specialization in the faculty; however, all specializations were related to management.

4. Results

The descriptive statistics and Cronbach’s coefficient alpha of the SISRI-24, the WLEIS and the Self-Leadership questionnaire, are presented in Table 1. Cronbach’s alpha were: 0.90 for the SISRI-24 total; 0.92 for the WLEIS total and 0.90 for Self-Leadership total. The reliability indicates an acceptable internal consistency (i.e., alpha = 0.70 or above). The reliability is also acceptable for all subscales. The means of the SISRI-24, WLEIS and Self-Leadership were assessed as average. Self-Leadership was assessed as the highest by the respondents (mean_2.98, stand. deviat_0.64); next was emotional intelligence (mean_2.38, stand. deviat_1.24). The average of emotional intelligence is slightly higher than spiritual intelligence that has the lowest rate (mean_2.06, stand. deviat_1,29). It can be noticed that the particular subscales were assessed differently—from 1.65 (CSE) to 3.11 (SL3). The results obtained show that students possess skills to manage their own tasks, they can set and achieve the goals, and they are reflexive, because they can analyze their performance and try to focus on the good aspects of their work. These skills can also be good for them as future leaders. The students also possess quite good abilities of management, especially controlling their own emotions. Appraisals of other emotions are more difficult for the respondents. The subscales of spiritual intelligence were assessed to be low. The lowest rate reached a conscious state expansion that, in general, sounds quite abstract.

Table 1.

Mean, standard deviation and Cronbach’s alpha of SISRI-24, the WLEIS and Self-Leadership.

The results of correlations between the SI, EI and SL and their subscales are shown in Table 2. There are positive and significant (p > 0.01) correlations between SI and EI (0.508); SI and LS (0.462); and EI and LS (0.631). The results support the hypotheses. All subscales of three constructs: spiritual intelligence, emotional intelligence and self-leadership, have positive correlations (from 0.195 to 0.556). The strongest correlations are between personal meaning production (PMP) and use of emotion (UE) (0.556, p > 0.01), appraisals of self-emotion (SE) (0.540, p > 0.01), and appraisals of other’s emotion (OE) (0.444, p > 0.01). Moreover, the rest of the subscales of spiritual intelligence, as well as emotional intelligence, have positive and significance correlations between each other, and with self-leadership. This means that these constructs and their subscales may influence each other and increase these abilities.

Table 2.

Correlation among the subscales of spiritual intelligence (SI), emotional intelligence (EI) and self-leadership (SL).

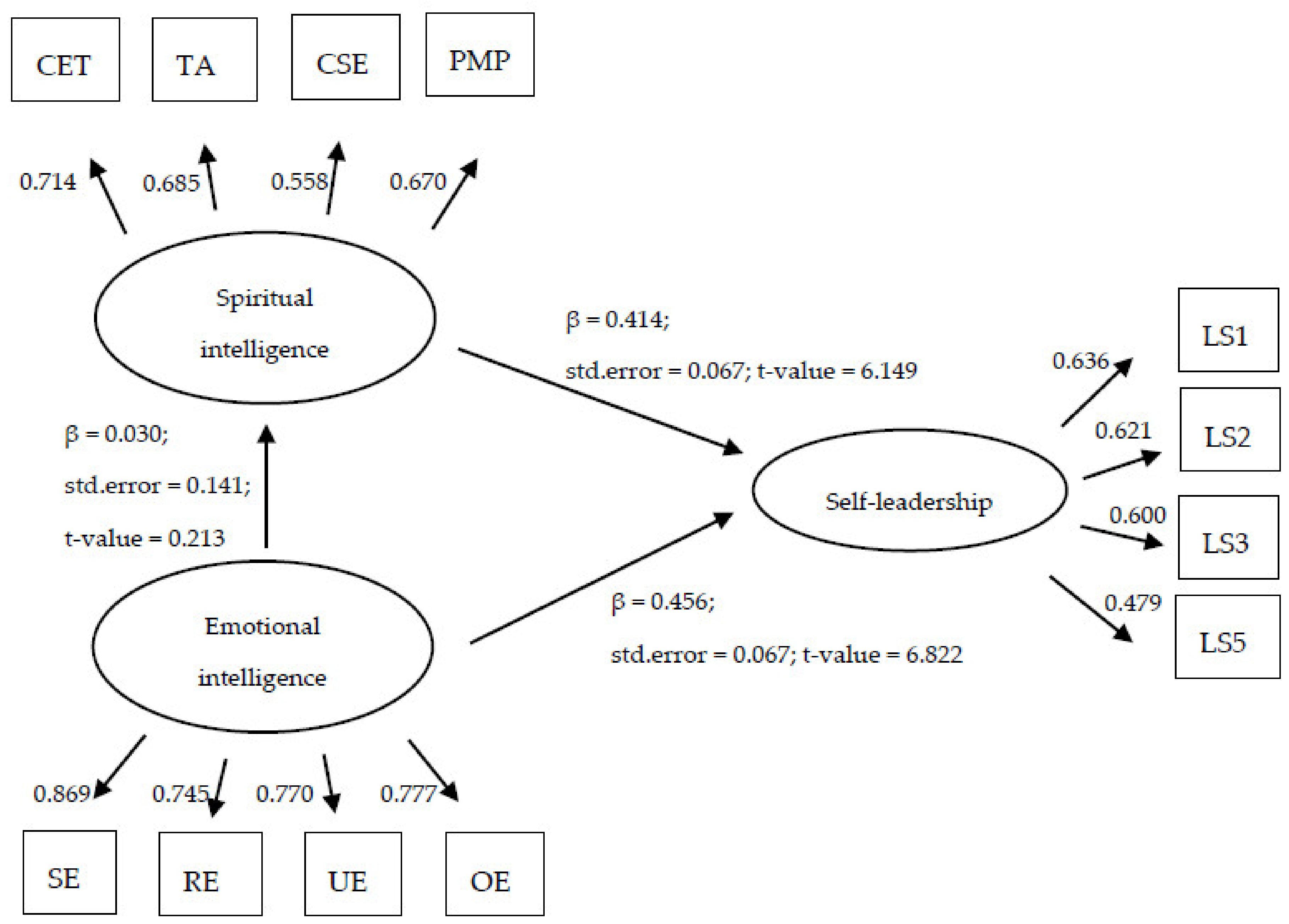

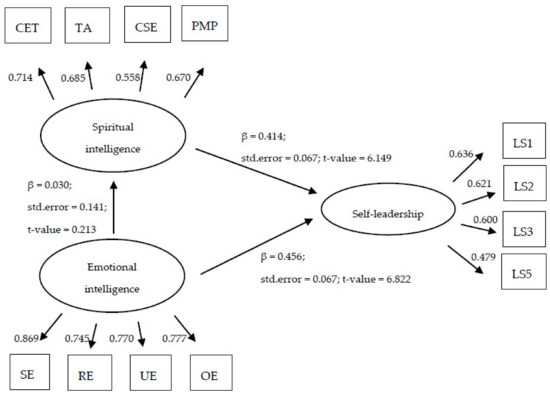

Table 3 and Figure 1 show the results of the structural model from the GLS-ML output. The confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to test the validity of the constructs. The Chi-square value, df, root mean square error approximation (RMSEA), goodness-of-fit index (GFI) and normed fit index (NFI) was applied for p > 0.05. RMSEA in both constructs: spiritual intelligence and self-leadership, is below 0.01 which means a very good fit; in the case of emotional intelligence, this is below 0.05, which means a satisfactory fit. Moreover, GFI (>0.9) and NFI (>0.9) confirm a good fit. However, the subscale SL4 (focus on natural reward) which forms the construct of self-leadership was removed, because of a poor fit. It should be noted that SL4 had the lowest Cronbach’s alpha indicator, as well as low Pearson correlations with other subscales from the above analysis.

Table 3.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) of the constructs of SI, EI and SL.

Figure 1.

SEM model of emotional and spiritual intelligence and self-leadership.

The SEM was used to test the factors that determine self-leadership (Figure 1). Perceived emotional intelligence was a significant predictor of self-leadership (β = 0.456, p > 0.05). Thus, the Hypothesis 1 was supported. The results obtained show that spiritual intelligence is also a significant factor (β = 0.414, p > 0.05) that supports the Hypothesis 2. These relationships mean that the higher the level of emotional and spiritual intelligence, the higher the level of self-leadership. It should be noted that spiritual intelligence is positively related to emotional intelligence (β = 0.030, p > 0.05), however, this relationship is not sufficient. Thus, this finding did not support Hypothesis 3.

The results of effects analysis for subscales of all three constructs presented significant positive correlations. CET (β = 0.714, p = 0.000), TA (β = 0.785, p = 0.000), CSE (β = 0.558, p = 0.000) and PMP (β = 0.670, p = 0.000) showed positive values with spiritual intelligence. SE (β = 0.869, p = 0.000), RE (β = 0.745, p = 0.000), UE (β = 0.770, p = 0.000) and OE (β = 0.777, p = 0.000) had positive values with emotional intelligence. All subscales of self-leadership also had positive values with the latent variable: LS1 (β = 0.636, p = 0.000), LS2 (β = 0.621, p = 0.000), LS3 (β = 0.600, p = 0.000) and LS5 (β = 0.479, p = 0.000).

5. Conclusions

The results of the study indicate that there is a significant and positive link between emotional and spiritual intelligence and the self-leadership of the students. Meanwhile, many previous research have indicated the correlation between emotional intelligence and leadership; this study draws attention to the fact that spiritual intelligence may also be important for leadership skills. Both kinds of intelligence are predictors of the ability of self-leadership. Self-leadership competence of the students can be useful in the future, when these students become leaders. To enhance leadership skills, emotional knowledge and spiritual knowledge may be considered as a subject in the leadership education program.

The results also presented that there is a link between emotional intelligence and spiritual intelligence, although it can be noticed that emotional intelligence is not a predictor of spiritual intelligence. Moreover, the results presented that both the spiritual intelligence and the emotional intelligence of the students had been assessed to be at quite average levels. Thus, the gap in possessing this kind of intelligence indicates that they should be strengthened under leadership courses for the development of leadership intelligence.

The results allow for the conclusion of some findings about the connection of spiritual and emotional intelligence and self-leadership in the context of education. The results showed that emotional knowledge should be further developed under the leadership education program, while spiritual knowledge should be introduced as a subject to the leadership education program. Education cannot be reduced to rational knowledge (as it is now) or emotional knowledge (which exists more often), but enhanced to include spiritual knowledge. Spirituality according to literature becomes a crucial success factor for an organization by creating a positive work environment, and has effects on positive emotions. Leadership education often pressures the significance of self-interest and profit-making as a main potency of building competitive advantage. However, the dynamic, volatile, and unpredictable circumstances in organizational environment force changes in the approach to leadership education. Thus, it seems that the theory of spiritual intelligence is worth being further developed and introduced to the leadership education program. It is significant for improving the quality of leadership education.

As a further direction of the research, it would be worth it to conduct other surveys to confirm the above results. Firstly, the quantitative survey using a questionnaire is based on self-reported data. This causes the questionnaire to measure the subjective perception of one’s own intelligence. Secondly, the structural equation modeling does not confirm the impact of emotional intelligence on spiritual intelligence. However, there is a positive link between these two constructs. It should be further developed to clearly confirm or exclude the correlation.

In conclusion, this study sheds light on recognition of the significance of emotional and spiritual intelligence of leaders. It can be inspired for expanding the theory of intelligence, especially spiritual intelligence that is still under research in the context of leadership education.

Funding

This research is supported by research work no. WI/WIZ-INZ/1/2020 at the Bialystok University of technology and financed from a subsidy provided by the Minister Of Science and Higher Education.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hacker, S.K.; Washington, M. Spiritual Intelligence: Going Beyond IQ and EQ to Develop Resilient Leaders. Glob. Bus. Org. Excel. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, N.S. Intelligence, Emotional and Spiritual Quotient as Elements of Effective Leadership. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Hum. 2013, 21, 315–328. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, R.K.; Sawaf, A. Executive EQ: Emotional Intelligence in Leadership and Organizations, Gosset; Putnam: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ljungholm, D.P. Emotional intelligence in organizational behavior. Econ. Manag. Financ. Mark. 2014, 9, 128–133. [Google Scholar]

- Stanescu, D.F.; Cicei, C.C. Leadership Styles and Emotional Intelligence of Romanian Public Managers. Evidences from an Exploratory Pilot Study. Rev. Res. Soc. Interv. 2012, 38, 107–121. [Google Scholar]

- Drigas, A.; Papoutsi, C. Emotional Intelligence as an Important Asset for HR in Organizations: Leaders and Employees. Int. J. Adv. Corp. Learn. 2019, 12, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goleman, D. Working with Emotional Intelligence; Bantam Books: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- McKee, A. The Public Sphere: An. Introduction; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zohar, D. ReWiring the Corporate Brain: Using the New Science to Rethink How We Structure and Lead Organizations; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Zohar, D.; Marshal, I. SQ: Spiritual Intelligence, the Ultimate Intelligence; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, S.J.; Shankman, M.L.; Migue, R.F. Emotionally Intelligent Leadership: An Integrative, Process-Oriented Theory of Student Leadership. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2012, 11, 177–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratianu, C. Emotional and Spiritual Knowledge. In Knowledge and Project Management: A Shared Approach to Improve Performance; Handzic, M., Bassi, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 69–94. [Google Scholar]

- Ariely, D. Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces that Shape Our Decisions; Harper Collins Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, D. Thinking, Fast and Slow; Farrar, Straus and Giroux: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Goleman, D. Emotional Intelligence; Bantam Books: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Day, D.V. Leadership development: A review in context. Leadersh. Q. 2000, 11, 581–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J.D.; Roberts, R.D.; Barsade, S.G. Human abilities: Emotional intelligence. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2008, 59, 507–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, L.; Stough, C. Examining the relationship between leadership and emotional intelligence in senior level managers. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2002, 23, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shutte, N.S.; Malouff, M.J.; Thorsteinsson, B.E. Increasing Emotional Intelligence through Training: Current Status and Future Directions. J. Emot. Educ. 2013, 5, 56–57. [Google Scholar]

- Maul, A. The Validity of the Mayer–Salovey–Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT) as a Measure of Emotional Intelligence. Emot. Rev. 2012, 4, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-On, R.; Parker, J.D.A. Emotional Quotient Inventory: Youth Version™ (EQ-i:YV™); Multi-Health Systems: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Goleman, D. What makes a leader? Harv. Bus. Rev. 1998, 76, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wong, C.S.; Law, K.S. The effects of leader and follower emotional intelligence on performance and attitude: An exploratory study. Leadersh. Q. 2002, 13, 243–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellett, J.B.; Humphrey, R.H.; Sleeth, R.G. Empathy and complex task performance: Two routes to leadership. Leadersh. Q. 2002, 13, 523–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, M.; Korkut, A. Spiritual Leadership in Primary Schools in Turkey. J. Educ. Soc. Res. 2015, 5, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Darwin, J. Emotional Intelligence and Mindfulness. 2015. Available online: http://mindfulenhance.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Emotional-Intelligence-andMindfulness.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2020).

- Rodríguez-Ledo, C.; Orejudo, S.; Cardoso, M.J.; Balaguer, Á.; Zarza-Alzugaray, J. Emotional Intelligence and Mindfulness: Relation and Enhancement in the Classroom with Adolescents. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 21–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, D.R.; Mayer, J.D.; Salovey, P. Relation of an ability measure of emotional intelligence to personality. J. Personal. Assess. 2002, 79, 306–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J.D.; Peter, S.; Caruso, D.R.; Sitareonis, G. Emotional intelligence as a standard intelligence. Am. Psychol. Assoc. 2001, 1, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, L.M.; Douglas, C.; Ferris, G.R.; Ammeter, A.P.; Buckley, M.R. Emotional intelligence, leadership effectiveness and team outcomes. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2003, 11, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kernbach, S.; Schutte, N.S. The impact of service provider emotional intelligence on customer satisfaction. J. Mark. 2005, 19, 330–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, M. Are Foreign Banks in China Homogenous? Classification of their Business Patterns. J. Account. Bus. Financ. Res. 2018, 3, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Bass, M.B. Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire Technical Manual, 3rd ed.; Mind Garden, Inc.: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; George, G.M. Awakening employee creativity: The role of leader emotional intelligence. Leadersh. Q. 2003, 14, 545–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahal, P.K. Influence of Emotional Intelligence on Employee Satisfaction: An Empirical Study of Banking Sector. J. Strateg. Hum. Res. Manag. 2016, 5, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, K.R.; Kumar, S. Emotional Intelligence and Managerial Effectiveness: A Comparative Study of Male and Female Managers. Indian J. Health Wellbeing 2016, 7, 244–247. [Google Scholar]

- Suan, S.C.T.; Anantharaman, R.N.; Kin, D.T.Y. Emotional Intelligence and Organizational Performance: A Framework. Glob. Bus. Manag. Res. 2015, 7, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.S.; Huang, T.C. The relationship of transformational leadership with group cohesiveness and emotional intelligence. Soc. Behav. Personal. 2009, 37, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, K.; McEnrue, M.P. Choosing among tests of emotional intelligence: What is the evidence? Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2006, 17, 9–42. [Google Scholar]

- Amram, Y.; Dryer, D.C. The integrated spiritual intelligence scale (ISIS): Development and preliminary validation. Presented at the 116th Annual Conference of the American Psychological Association, Boston, MA, USA, 14–17 August 2008. [Google Scholar]

- King, D.B. Rethinking Claims of Spiritual Intelligence: A Definition, Model, and Measure. Master’s Thesis, Trent University, Peterborough, Ontario, 2008. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Emmons, R.A. Spirituality and intelligence: Problems and prospects. Int. J. Psychol. Relig. 2000, 10, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, F. What is spiritual intelligence? J. Human. Psychol. 2002, 42, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, M. Spiritual Intelligence, Awakening the Power of Your Spirituality and Intuition; Hodder & Stoughton: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Emmons, R.A. Is spirituality an intelligence? Motivation, cognition, and the psychology of ultimate concern. Int. J. Psychol. Relig. 2000, 10, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, K.D. Spiritual intelligence: A new frame of mind. Adv. Dev. 2000, 9, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Wigglesworth, C. SQ21: The Twenty-One Skills of Spiritual Intelligence; SelectBooks, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dåderman, A.M.; Ronthy, M.; Ekegren, M.; Mårdberg, B.E. Managing with my heart, brain and soul: The development of the leadership intelligence questionnaire. J. Coop. Educ. Internsh. 2013, 47, 61–77. [Google Scholar]

- King, D.B.; DeCicco, T.L. A viable model and self-report measure of spiritual intelligence. Int. J. Transpers. Stud. 2009, 28, 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, W.L. Spiritual Leadership; Springer International Publishing: Basel, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronthy, M. Leader Intelligence: How You Can Develop Your Leader Intelligence with the Help of Your Soul, Heart and Mind; Amfora Future Dialogue AB: Stockholm, Sweden, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Selver, P. Spiritual Values In Leadership and the Effects on Organizational Performance: A Literature Review; University of Northern British, Columbia: Prince George, BC, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fry, L.W.; Cohen, M.P. Spiritual leadership as a paradigm for organizational transformation and recovery from extended work hour cultures. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 84, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J. Business and the spirit: Management practices that sustain values. In Handbook of Workplace Spirituality and Organizational Performance; Giacalone, R.A., Jurkiewicz, C.L., Eds.; M.E. Sharp. Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 27–43. [Google Scholar]

- Samul, J. Spiritual leadership: Meaning in the sustainable workplace. Sustainability 2020, 12, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunsaker, W.D. Spiritual leadership and organizational citizenship behavior: Relationship with Confucian values. J. Manag. Spiritual. Relig. 2016, 13, 206–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Saane, J. Personal leadership as form of spirituality. In Leading in a VUCA World: Integrating Leadership, Discernment and Spirituality; Kok, J.K., van den Heuvel, S.C., Eds.; Contributions to Management Science, Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, L.H.; Ramos, R.R.; Ramos, S.R. Spiritual behaviour in the workplace as a topic for research. J. Manag. Spiritual. Relig. 2009, 6, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, K.S.; Passmore, D.L.; Lee, C.; Hunsaker, W. Spiritual leadership: A validation study in a Korean context. J. Manag. Spiritual. Relig. 2013, 10, 342–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zellers, K.L.; Perrewe, P.L. Handbook of Workplace Spirituality and Organizational Performance; Giacalone, R.A., Jurkiewicz, C.L., Eds.; M.E. Sharp. Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 300–313. [Google Scholar]

- Geula, K. Emotional intelligence and spiritual development. Paper Presented at the Forum for Integrated Education and Educational Reform sponsored by the Council for Global Integrative Education, Santa Cruz, CA, USA, 28–30 October 2004; Available online: http://chiron.valdosta.edu/whuitt/CGIE/guela.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2020).

- Kurniawan, A.; Syakur, A. The Correlation of Emotional Intelligence and Spiritual of Intelligence to Effectiveness Principals of Leadership. Int. J. Psychol. Brain Sci. 2017, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, M.A.; Gani, A.M.O.; Rahman, M.S. Effects of spiritual intelligence from Islamic perspective on emotional intelligence. J. Islamic Account. Bus. Res. 2020, 11, 216–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selman, V.; Selman, R.C.; Selman, J.; Selman, E. Spiritual-Intelligence/-quotient. Coll. Teach. Methods Styles J. 2005, 1, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libbrecht, N.; Lievens, F.; Schollaert, E. Measurement Equivalence of the Wong and Law Emotional Intelligence Scale Across Self and Other Ratings. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2010, 70, 1007–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghton, J.D.; Neck, C.P. The revised self-leadership questionnaire: Testing a hierarchical factor structure for self-leadership. J. Manag. Psychol. 2002, 17, 672–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).