Abstract

This paper looks at the effects of an intervention, based on fluency oriented reading instruction (FORI), on the motivation for reading among struggling readers in First Class in Irish primary schools. The intervention took place in learning support settings in three primary schools located in urban educationally disadvantaged communities in North Dublin. The study was conducted through a pragmatic lens with research questions framed to shed light on the motivation for reading of students in First Class from disadvantaged backgrounds. A mixed methods design with a concurrent triangulation strategy was employed, facilitating the exploration of multiple research questions using questionnaires and semi-structured interviews with teachers and parents and conversational interviews and surveys with students. The perspective of reading motivation guiding the study recognised the overlapping influences of teachers, parents and the student himself or herself. Findings, as reported by these research informants, indicate that the FORI intervention had a positive impact on the motivation for reading of struggling readers in First Class. In particular, the intervention was found to decrease students’ perceived difficulty with reading and increase their reading self-efficacy and orientation towards reading.

1. Introduction

In today’s society, it is critical that every child has the fullest opportunity to become an accomplished reader. Instructional strategies in reading are continually debated as the quality of an individual’s life is affected by their literacy competence, which in turn is essential for an individual’s personal and social fulfilment. The consequences of not learning to read proficiently are enormous, with those failing in this regard facing personal, social and economic limitations [1]. Internationally, there has been considerable interest in identifying ways in which to improve literacy standards and so avert the aforementioned consequences. In Ireland, despite the level of interest focused on improving literacy standards and the magnitude of policies in this regard, many students, particularly those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, continue to have difficulty achieving success in reading [2].

1.1. Background

The most common approach to assist children who present with reading difficulties in Irish primary schools is to withdraw them from the regular classroom and provide learning support tuition either individually or in smaller groups [3,4]. Research on the nature of reading instruction provided in these withdrawal settings indicates an emphasis on cognitive and metacognitive processes with less attention paid to motivational instruction and the role played by affective factors [5,6,7]. However, the affective aspects of reading have been shown to contribute unique variance to reading achievement, and differences in reading attitude and motivation have been implicated in the socioeconomic gaps in reading achievement found consistently worldwide [8,9,10,11]. Young students, who have difficulties in learning to read, need to be particularly motivated in order to engage in a process where they have already experienced failure [7]. The extent to which they are motivated by their early reading instruction, therefore, has a significant impact on the likelihood of them succeeding in reading, which in turn can impact on their school experiences in later years [12]. Consequently, finding ways to motivate young children to read is identified as a priority in reading research [13].

This paper presents the results of research carried out on the effects of fluency oriented reading instruction (FORI) on the motivation for reading among struggling readers from areas of low socioeconomic status. Research in the area of motivation has an extensive history and has long been regarded as having a key role in reading achievement [14]. Hence, a better understanding of the relationship between fluency oriented reading instruction and motivation to read has practical and theoretical implications. If this particular type of reading instruction is found to significantly impact on motivation to read, this would indicate a need to focus more on improving oral reading fluency skills. Conversely if motivation to read has a subsequent and sustainable effect on reading skill development, this would indicate a need to integrate more techniques into early reading instruction that are focused on improving student motivation to read as well as techniques that specific reading skills.

1.2. Description of Study

The study, which was conducted in three disadvantaged primary schools in the Dublin Northside Partnership catchment area, examined the effects of an on-site reading intervention on the motivation for reading of struggling readers. The intervention, which was based on fluency oriented reading instruction, took place in learning support classrooms in these schools. The research focused on students in First Class who were receiving learning support for reading and were identified as having poor motivation for reading. The study is specifically focused on students in First Class as research has shown this to be a critical period of rapid skill development that can take readers from word-by-word reading to fluent speech-like reading by the end of that grade [15,16].

1.3. Rationale for Fluency Oriented Reading Instruction

Helping students become fluent readers is a central goal of early reading instruction [17,18,19]. Students who do not develop reading fluency by the middle grades of primary school normally struggle with reading throughout their lives [20,21]. While numerous reading theories and a wide range of research have focused on explaining how children learn to read [20,22,23], there is still much debate amongst reading researchers, parents and teachers over which types of early reading instruction are most effective [24,25,26]. In addition to early reading instruction that focuses on phonics, word decoding skills, vocabulary development, and comprehension, reading instruction that builds a child’s oral reading fluency is now considered by some reading researchers to be a vital but often neglected element of a balanced reading programme [18,20,21,27].

Fluency oriented instruction was selected based on research indicating that reading fluency is an important factor when considering a reading intervention for students experiencing difficulties with reading in the early years of primary school [28]. Oral reading fluency is seen as fundamental to the holistic development of reading skills as children move from word-by-word to fluent, expressive reading [29,30,31]. It has been identified as a particularly salient factor when considering the achievement, or lack of achievement, for young struggling readers who have a greater deficit in reading fluency than in word recognition or comprehension [30,31]. Other research suggests that word recognition and reading fluency difficulties may be the key concern for upwards of 90% of children with significant problems in reading comprehension [32].

1.4. Fluency Oriented Instruction and Struggling Readers

Fluency in any activity is achieved largely through practice and repetition—the musician rehearses, the athlete engages in training drills, the actor spends time rehearsing pieces that will eventually be performed on stage, and the child learning to ride a bike spends hours repeating the same basic skills in a quest for competence. The practice referred to in these contexts involves the repetition of a particular tune, skill, movement, or composition many times. Similarly, fluency is achieved in reading through repeated practice of selected texts. While skilled and competent readers who have mastered decoding (word recognition) are often able to achieve and maintain fluency in reading through wide and independent reading, for poor readers, repeated reading of the same text is an essential method for achieving fluency [18,33]. Research on repeated reading as an instructional strategy indicates that when students orally practiced a piece of text they improved on their rate, accuracy and reading comprehension of that text [34]. Such an accomplishment is to be expected given the same text is revisited many times. However, it is also found that when students moved to new passages, their initial readings of those new pieces are read with higher levels of fluency and comprehension than the initial readings of the previous passage, even though the new passage was as difficult as or more challenging than the previous piece [33].

1.5. Motivation and Reading

Traditionally, research carried out on motivation as it pertained to education focused mainly on the concept of achievement or academic motivation as a broad construct generalized across all domains in a child’s academic experience. Only in the relatively recent past has research focused on the intersection of motivation and reading achievement [7,35]. Researchers and educators who have conducted investigations specifically in the field of motivation for reading have found the concept to be multifaceted with a recognition of the affective domain as a critical element in reading instruction [36,37]. Once the affective aspects of reading were recognised as important in skill development [36], a variety of constructs were posited by theorists to explain reading motivation and how it influences students’ reading engagement [38,39].

Since the ultimate goal of literacy instruction is ‘the development of readers who can read and who choose to read’ [40] (p. 19), it is now generally accepted by teachers of young children that reading motivation plays a critical role in reading development [41,42]. Research on motivation has thus provided compelling evidence that success in reading demands the integration of cognitive, language and motivational engagement [37]. Recently, there has been a growing interest in the impact of motivation in the early years, leading researchers to focus specifically on the motivation of readers in the lower grades [43,44,45]. Researchers in this area argue that it is still unclear how broad the construct of reading motivation needs to be to capture the early development of reading skills [46]. What is clear is that there are a variety of possible reading motivations that can influence children’s engagement in reading and their reading performance [47,48].

1.6. Importance of Motivation for Struggling Readers

Research has indicated that up to ten percent of the variance in reading performance measures of students in the higher primary class levels is attributed to reading motivation [49]. If individuals believe they can be successful at an activity they strive to master that task. As students become more motivated to engage in the reading process, they are subsequently more likely to be successful [50]. Therefore, students who experience instruction that increases their motivation for reading at an early stage in their schooling are more likely to have a positive academic self-concept. Conversely, a lack of student engagement with literacy is identified in the literature as a fundamental obstacle to achievement in our schools [51] with the likelihood that struggling readers become poorly motivated to read if they repeatedly experience failure in acquiring even the basic reading skills [52,53].

Some researchers have proposed that poor motivation may be a defining feature of reading failure [54,55]. Children at risk for reading failure are likely to hold more negative self-concepts [53,56,57], display less emotional self-regulation [58], and avoid reading activities [59,60]. Morgan and Fuchs [41] in reviewing the research on reading motivation presented a number of studies that point towards a bidirectional relationship between motivation to read and reading skill development. Students tend to read competently and more frequently and without fear of failure when they are motivated to engage in the process [47]. Conversely, children who struggle with reading frequently become de-motivated, read less and become even weaker readers as they progress through the grades [61]. For this reason, motivation can be a compensatory factor, potentially mediating other discrepancies of struggling readers by creating a cycle of increased competence, increased motivation, and increased reading amount [62].

2. Methodology

This study draws on the theoretical perspective of multiple goals in motivation [63]. In particular, the research is grounded in the work of Eccles on expectancy–value theory of motivation [64]. Consistent with expectancy–value perspectives, the study focuses on the research of Guthrie, Coddington and Wigfield [65], who suggest reading orientation and perceived reading difficulty as fundamental constructs in examining reading motivation and on the work of Wigfield et al. [49], who emphasised the role of self-efficacy in reading as a critical construct of motivation. Accordingly, these three constructs of motivation (self-efficacy, reading orientation, and perceived reading difficulty) were selected for this study based on their potential for influencing the development of reading skill in the early primary school years. In this study reading orientation relates predominantly to students’ interest in reading and their attitude toward reading.

The study was conducted through a pragmatic lens, with research questions framed to shed light on the motivation for reading of students in First Class from disadvantaged backgrounds. A mixed methods concurrent triangulation strategy was adopted to gather data from teachers (both class teachers and learning support teachers), students and their parents. In this triangulation approach both quantitative and qualitative data were collected concurrently providing cross-validation and an opportunity to determine whether there was convergence, differences or a combination of both in the data. A summary of the data sources including questionnaires and semi-structured interviews with teachers and parents and conversational interviews and surveys with students is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Data sources for assessing motivation for reading.

2.1. Research Questions

The research carried out in the course of the intervention examined the effects of fluency oriented reading instruction (FORI) on three reading motivation constructs: reading self-efficacy, reading orientation, and perceived difficulty with reading. In particular, the study sought to investigate the following research questions:

- What are the effects of FORI on the reading self-efficacy of struggling readers?

- What are the effects of FORI on the reading orientation of struggling readers?

- What are the effects FORI on the perceived difficulty with reading of struggling readers?

2.2. The Research Subjects and Participants

The research subjects for the intervention were fifteen students in First Class who were struggling readers and were identified as being poorly motivated for reading. All students (eight boys and seven girls) were between the ages of six years one month and seven years two months at the beginning of the study with a mean age of six years, ten months. The student cohort, located across three research sites, represented seven different nationalities and included one child from the travelling community. (The Travelling community is an Irish ethnic minority group whose members maintain a set of traditions language, culture and customs. The distinctive Traveller identity and culture, based on a nomadic tradition, sets Travellers apart from the sedentary population or ‘settled people’ of Ireland.) The other research participants for the intervention were three learning support teachers, five grade teachers (First Class) and the parents of the participating students.

2.3. Data Collection

The motivation for reading of struggling readers was assessed before and after the reading intervention using the Young Reader Motivation Questionnaire—Student Form (S—YRMQ). The items on this questionnaire were derived from two standard questionnaires—the Young Reader Motivation Questionnaire [43] and the Me and My Reading Survey [66]—and were adapted to the aims of the study. This survey was chosen over more commonly used instruments such as Wigfield, Guthrie, and McGough’s [67] Motivation for Reading Questionnaire because it was designed to be used with younger children. The S—YRMQ was composed of three subscales to represent the three motivational constructs to be assessed. The Efficacy for Reading subscale of the S—YRMQ included six items, e.g., “Do you think you read well?” and “Are you good at remembering words you have seen before?” The Reading Orientation subscale of the S—YRMQ included ten items, e.g., “Is it fun for you when you read books?” and “Do you like to read during your free time or do something else?” while the Perceptions of Difficulty subscale of the S—YRMQ included six items, e.g., “Are the books you read in class too hard?” and “Do you need to get some extra help in reading?” The S—YRMQ was administered to each child individually at the beginning of the intervention and again at the completion of their series of lessons.

Student’s motivation for reading was also assessed using the teacher form of the Young Reader Motivation to Read—Teacher Rating (T-YRMR). This form was designed to parallel the student rating form with questions worded to reflect teachers’ perceptions of their students’ motivation for reading. Class teachers and learning support teachers completed this questionnaire. The T-YRMR featured 20 items spread across three subscales: Perceptions of Student Self-Efficacy for Reading, Perceptions of Student Reading Orientation, and Perceptions of Student Difficulty in Reading. All items were worded in declarative format, e.g., “This student thinks he/she is good at remembering words”; “This student thinks it is fun to read books”. Teachers responded to each item on a 4-point scale (1 = No, Never; 2 = No, Not Usually; 3 = Yes, Sometimes; 4 = Yes, Always). Two additional Likert-style questions were included in the questionnaire to gauge teachers’ overall view of each child’s achievement level in reading for their age and their overall level of motivation for reading.

Qualitative measures were used to triangulate the evidence from these survey instruments by conducting semi-structured interviews with the teachers and conversational interviews with the students. These conversational interviews were also conducted with the students six months after the intervention to explore enduring effects of the intervention. Individual semi-structured interviews and focus group interviews were also held with parents to triangulate data on student’s motivation for reading. These interviews took place before and after the intervention and again six months later.

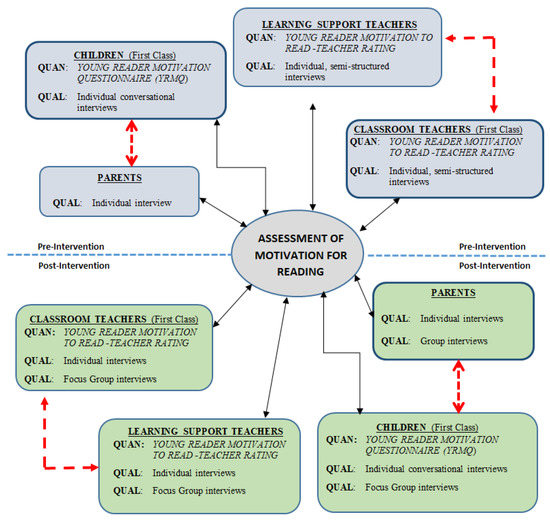

The concurrent gathering of information throughout this phase provided cross-validation and multiple opportunities to determine whether there was convergence in the data. An elucidation of the triangulation of data to ascertain motivation for reading is presented in Figure 1 where details of the research carried out is illustrated. Bi-directional dotted arrows indicate where comparison of data was used between students and parents and between classroom teachers and learning support teachers to triangulate assessment of student’s motivation for reading both pre and post intervention.

Figure 1.

Assessment of motivation for reading (concurrent triangulation design).

Teacher Questionnaire Validity

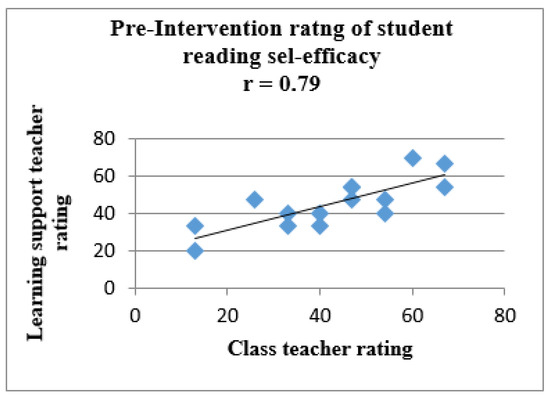

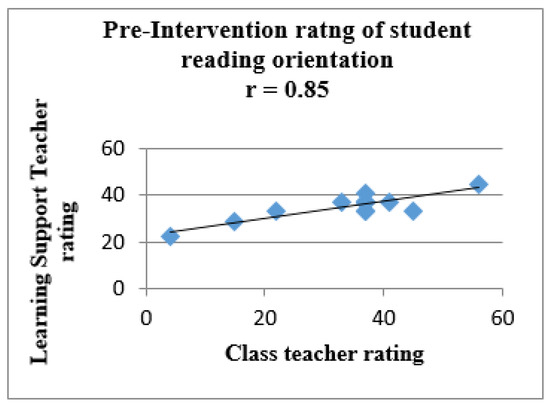

As the same questionnaire was completed independently for each student by learning support teachers and class teachers, a valuable validity check on the instrument was possible. Initial inspection of the scores reveals that learning support teachers and class teachers reported very similar ratings for individual students on the reading efficacy and reading orientation subscales. Closer statistical analysis carried out on the ratings reveal a close clustering of scores along the linear trendline, indicating positive correlation coefficients (r = 0.79; r = 0.85) between responses (see Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Correlation between teacher ratings of student reading self-efficacy.

Figure 3.

Correlation between teacher ratings of student reading orientation.

2.4. The Reading Intervention

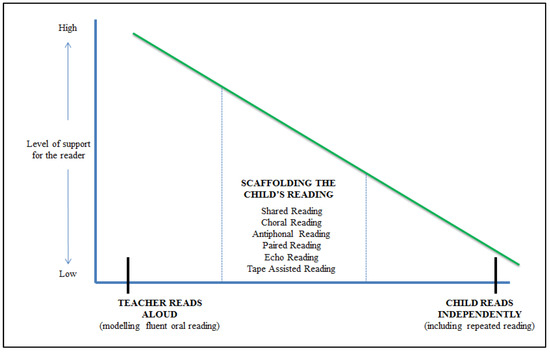

The intervention, based on fluency oriented reading instruction (FORI), took place over an eight-week period in three schools. Each day, learning support teachers in these schools instructed struggling readers who were withdrawn from their base class and were taught in groups of five in a learning support room. The fluency oriented reading instruction used in the study was an adaptation of an approach to reading instruction developed by Stahl and Huebach [68]. It was designed to increase the oral reading fluency of the students over the course of the intervention with the hypothesis that this type of instruction would also have a positive influence on their motivation for reading. The intervention featured the gradual release of support from a more knowledgeable reader (in this case the learning support teacher) towards independent reading by the students over the course of a unit of instruction (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Gradual release of responsibility: from modelling to independent reading.

At the beginning of each unit, the learning support teacher carried out full responsibility for modelling a fluent rendering of the text, with a view that the students would be able to read the same text independently by the end of the unit. The programme was agreed by the participating teachers and featured consistent elements such as modelling fluent reading, assisted guided oral reading instruction (e.g., echo reading, choral reading, antiphonal reading, and paired reading), partner reading and home reading. Word study and syntax activities were also integral elements of the intervention to ensure students had opportunities to build up their sight word knowledge in order to recognise words quickly.

Research on reading instruction indicates that students need plenty of opportunities to read significant amounts of connected text to learn to read fluently [68,69,70]. Hence, a feature of the intervention was the repeated reading and timed repeated reading of the same text to improve students’ automatic word recognition along with their use of appropriate expression. To ensure that students were not bored or fatigued by using the same text, a wide variety of fluency related activities were designed based on all texts. At the beginning of each unit the learning support teachers were furnished with multiple copies of the selected core text and a set of resources for each planned activity in the unit.

The intervention was divided into four units of instruction, with each one focused on fluency-related activities built around a single text. Each unit was taught over two consecutive weeks using a pre-determined fluency oriented reading instruction programme for each week (see Table 2). The first lesson of each unit commenced with the teachers presenting the text with a variety of pre-reading activities that introduced the characters and the seminal vocabulary of the narrative. The teachers read aloud from the appropriate text while the students followed along using their text. On the second day of the unit of instruction, the teachers asked the students to echo read the text.

Table 2.

Sample weekly plan for fluency oriented reading instruction (week one of a single unit).

On the third day of the unit, teachers asked their students to perform a choral reading of the passage. The students were engaged in partner reading of the text on day four of the unit. The fifth day of instruction each week involved performance-related activities designed to motivate pupils to continue to participate in the intervention and to engage students in activities such as timed repeated reading and cumulative choral reading.

A constant feature of the intervention was the requirement that students read passages from the core text at home each day and have a parent or guardian sign a home reading log. This was an important element of the intervention as it ensured that parents were kept informed of progress and remained involved in the process. In the second week of the instructional unit, the emphasis was on increasing students’ motivation to read by engaging in a variety of reading activities that encouraged the students to read with increased decoding speed and accuracy. Teachers recorded the use of these core fluency oriented activities (e.g., word dash, timed repeated reading, phrase reading) in an instructional log. The motivational aspect of the intervention was increased by the students recording their progress in these reading activities over the week in their FORI journals. Prosodic elements of fluent reading were also addressed in the second week of each unit when students were introduced to play scripts incorporating vocabulary from the core narratives. Students re-read these scripts in order to prepare for a Readers Theatre performance on the final day of each unit. This strategy, which combined reading practice and performing, enhanced students’ reading skills and confidence by having them practice reading with a purpose.

Intervention Fidelity

Learning support teachers were trained in all of the FORI lessons before administering them. Additionally, all lessons were written out as scripts to help ensure the planned lessons were adhered to and that there was uniformity of instruction across teachers and groups. To determine the fidelity of the lessons, a minimum of three instructional sessions were observed each week. For each lesson, teachers were expected to include a minimum of two core FORI activities. Similarly, for the sessions involving a performance lesson, the teachers were to afford each student the opportunity to perform independently on a previously rehearsed fluency oriented task. Finally, students were inevitably absent for an occasional instructional day due to illness, for example, or their class being involved in another activity. When students missed a lesson, catch-up sessions were held to instruct them on the content of the lesson, either in a group or individually. Across all sites and over the period of the intervention, a total of four students required such catch-up sessions. Thus, all students received instruction on all FORI lessons.

2.5. Teacher Professional Development

Prior to the intervention, the learning support teachers in this study participated in approximately fifteen hours professional development on fluency oriented reading instruction and aspects of reading intervention design. During the seminars, teachers were familiarised with the instructional models to be employed and were given sample lesson plans for the implementation of the proposed intervention. Seminars included videotapes that introduced oral reading fluency instructional strategies and that modelled the proper execution of fluency oriented instruction. Discussions were facilitated with the teachers regarding the integration of the proposed instructional approach into their own individual learning support programmes. During these seminars the teachers were encouraged to talk about what was going on in their respective classrooms and to work through any concerns and questions they had with implementing the proposed fluency oriented reading instruction. Materials for this instruction were identified (and in some cases designed) as part of the professional preparation for the intervention. In the course of these seminars, four levelled reading texts were identified and chosen as the focus for the intervention. These texts had reading levels that correlated closely to other books already in use in the three schools. The texts, though short, were interesting enough to warrant discussion and vocabulary instruction on individual words and were selected based on their suitability for the type of reading instruction planned. They had carefully controlled language, repetitive patterns and repeated vocabulary and were suitable for fluency oriented reading instruction and for repeated reading in particular.

2.6. Scoring the Motivation for Reading Questionnaires

For analysis purposes, and to triangulate the findings from the surveys with qualitative data, an overall reading motivation percentage score for each construct was derived from both the student questionnaires and the teacher questionnaires before and after the intervention.

2.6.1. Scoring the Student Survey (S—YRMQ)

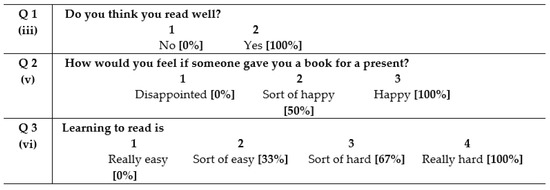

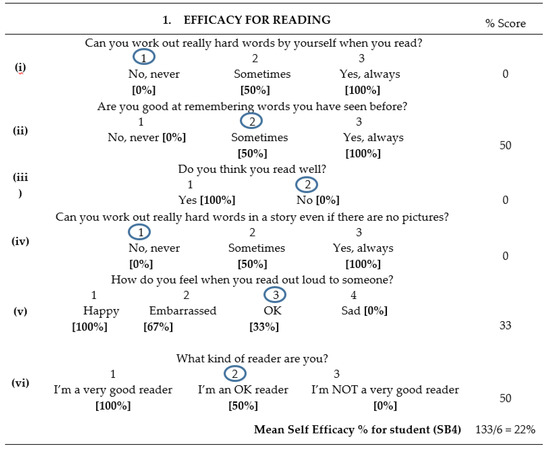

The Student Survey (S—YRMQ) comprised twenty-two multiple choice items with the set of potential answers for individual survey questions ranging from two to four possible responses. In order to quantify the level of motivation for each item, a percentage score was assigned to the nature of a response dependent on the number of answers to individual questions that were offered to students. For example, in the case of the sections assessing reading self-efficacy and reading orientation, zero percent (0%) was assigned to the most negative response with one hundred percent (100%) representing the optimum positive answer. Items in the third section that assessed students’ perceived reading difficulty were phrased in such a manner that if a student answered ‘yes’ or ‘always,’ it represented a high level of difficulty and percentages were assigned accordingly. Examples of percentages assigned to individual responses across the range of multiple choice questions can be seen in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Coding for motivation for reading survey (student form).

For analysis purposes, and to triangulate the findings from the surveys with qualitative data, an overall reading motivation percentage score for each construct was derived. This was achieved by scoring the individual student response on each item and then calculating the average percentage score for all students in each construct. The pre-intervention motivation scores for the students in one research site (School A) across all three constructs are presented in Table 3 as an example. The percentages included in this table represent the student self-rating responses only, with the reading efficacy percentage score for one student (SB4) highlighted for illustrative purposes. The figure of 22 percent for this student represents an average score for this construct derived from responses to the six items featured in the section on reading efficacy.

Table 3.

Example of student self-rating scores (pre-intervention).

The responses of this student (SB4) to questions on efficacy for reading, administered before the intervention, are presented in Figure 6 along with earned percentage scores.

Figure 6.

Example of scoring of quantitative measures (Student SB4: reading efficacy).

2.6.2. Scoring the Teacher Survey (T-YRMR)

The Teacher Survey (T-YRMR) comprised 20 statements organised in three sections reflecting the constructs of reading motivation assessed in the study. Teachers were asked to rate the likelihood of a particular behaviour occurring and were given a selection of four potential answers: (i) No, never, (ii) No, not usually, (iii) Yes, sometimes, or (iv) Yes, always. The optimum positive response (Yes, always) was assigned 100%, with scaled scores down to 0% for the most negative response. In instances where the statements were phrased in the negative form, e.g., ‘the student avoids participation in reading activities’, 100% was assigned to the “No, never” response with the scoring scaled down to 0% for the “Yes, always” response.

2.6.3. Data Analysis for Interviews

The transcripts for interviews with teachers and parents and for conversational interviews with students for this phase of the study were coded in order to identify the source of the data and to ensure quotes could be traced back to the original transcript. In coding all these variables, for convenience, the letters A, B and C were assigned to the three schools to identify the three different sites. For example, using this method, data from the learning support teacher in School A was coded as LSA1, data from a particular student in School B received the coding SB1, SB2 and data from a parent focus group in School C was coded as PFGC. Interviews were categorised according to four major themes reflecting the research questions for this phase of the study and were also assigned a descriptive code. For example, quotes referring to the motivational constructs of self-efficacy, reading orientation and perceived difficulty with reading were assigned SE, RO and PRD, respectively. After each piece of data had been assigned a code, a further layer of analysis was conducted to extract and deduce the meaning of each one. Each quote that warranted inclusion was then numbered within the category for reference purposes.

3. Results

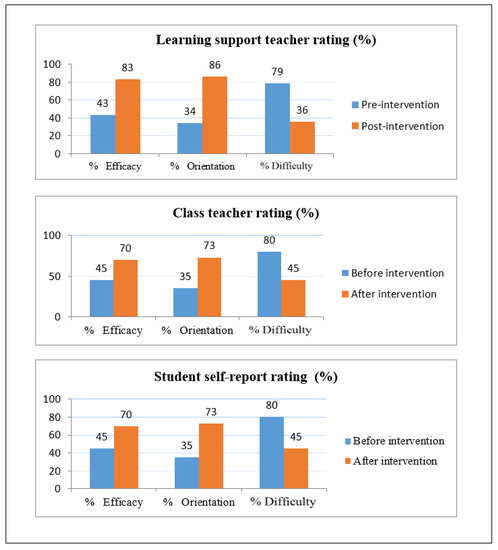

The impact of FORI on the motivation for reading were analysed in the context of a chorus of research voices representing teachers, parents and students. One major conclusion drawn from the study is that FORI, involving a gradual release of responsibility from the teacher to the student, impacts positively on the motivation for reading of struggling readers. This is based on a comprehensive set of data generated by teachers, parents and students on the assessment of reading self-efficacy, reading orientation and perceived reading difficulty before and after the intervention. The quantitative results of both teacher and student surveys of reading motivation are reported here in summative form. Qualitative data from the interviews conducted with all research informants support these findings and are included in the discussion section of this paper.

3.1. Reading Self-Efficacy of Students

The data from post-intervention surveys and interviews was analysed to directly examine the effects of FORI on the reading efficacy of the participating students. A comparison of the results from the surveys carried out pre- and post-intervention with teachers and students is presented in Table 4 with the mean percentage increase in the rating for reading efficacy for students identified.

Table 4.

Percentage rating for reading self-efficacy (pre- and post-intervention).

The findings and analysis suggest that the FORI method, as implemented in the current study, had a positive effect on the reading self-efficacy of struggling readers.

3.2. Reading Orientation of Students

The findings from the post-intervention surveys reveal the resoundingly positive impact that the FORI intervention had on students’ reading orientation as rated by learning support teachers, class teachers and students. The results from all surveys are presented in Table 5 with pre- and post-intervention data side by side for comparison purposes. The percentage increase in the reading orientation for students, as rated by teachers and students is highlighted with the overall mean rating for the cohort indicated in all cases.

Table 5.

Percentage rating for reading orientation (pre- and post-intervention).

A correlation coefficient of 0.69 for ratings by both sets of teachers indicated a convergence of views on the effects of the intervention on individual students. The mean increase in reading orientation for each student as calculated from all three surveys of 36 percent reported here represents a positive effect of the intervention on reading orientation.

3.3. Perceived Reading Difficulty of Students

The third motivational construct provided the context for examining the extent to which students perceived reading tasks as challenging or problematic. For the teachers, student reading difficulty was defined as the belief that ‘reading activities are hard or problematic’ for the child [71] (p. 154). The results of both surveys indicate a high percentage of perceived reading difficulty as reported at the outset of the study by teachers and students (see Table 6).

Table 6.

Percentage rating for perceived reading difficulty (pre- and post-intervention).

Results from quantitative measures employed after the intervention indicate that perceptions of reading difficulty as self-reported by students were significantly reduced. An overall mean rating for perceived reading difficulty of just 29 percent represented an average decrease of 39% per student over the period of the intervention. It is important to remember that, in the data analysis for this construct, a reduced percentage rating represents a positive effect of the intervention.

3.4. Statistical Analysis of Reading Motivation Findings

Were there changes over time in the responses in relation to students’ motivation for reading? In other words, did responses by teachers and students significantly differ from the time they were given the questionnaire before the intervention and, again, after the intervention? Total questionnaire responses (pre- versus post-intervention) were compared through the Wilcoxon signed-rank test (paired difference test). In testing the related samples for statistical significance, it was necessary to compare results for all three research informants across the three constructs of motivation included in this study. Hence, statistical information was required on nine discrete comparisons. Results indicated that responses of students did change over time in significant and positive ways. All nine comparisons showed a significant difference for pre- and post-intervention (see Table 7). For example, students’ responses on the post-intervention questionnaire in relation to their self-efficacy for reading (x̅ = 82.7, σ = 16.3) were significantly different from their responses on the questionnaire administered before the intervention (x̅ = 55.1, σ = 14.92), z = −3.4, p < 0.001. This means that for all three data sources a significant post-intervention improvement was found in perceptions of students’ reading efficacy, reading orientation and perceived reading difficulty.

Table 7.

Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

These statistically significant findings theoretically corroborate the relationship between motivation for reading and fluency oriented instruction [72,73]. This evidence strongly supports the hypothesis that fluency oriented reading instruction has a positive influence on the motivation for reading of struggling readers. A summary of quantitative measures of these effects, as reported by teachers and students, is presented compositely in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Impact of FORI on student motivation across three constructs.

4. Discussion

As demonstrated above, findings, as reported by all research informants, indicate that the FORI intervention had a positive impact on the motivation for reading of struggling readers in First Class. The impact on students’ motivation for reading derived from quantitative measures was supplemented by evidence gathered during the course of the intervention through interviews, reflective journals and field notes. The major assertion generated from this qualitative evidence after the intervention was that all students had an increased belief in their ability to read well and that the daunting task of reading challenging texts was no longer insurmountable. In addition to students’ growing belief in their ability to read due to mastering the basic skills, all teachers noted an increase in confidence among students reading without the fear of failure. This confidence in their ability as readers was attributed in some instances to the nature of the FORI activities, as exemplified by the comment of one learning support teacher:

“The way that we conducted the lessons for each unit had a real effect on the children’s confidence and self-concept around reading. When they are asked to read there is no fear of making a mistake....even the weakest readers in my group experienced success in every lesson. Of course they still struggled on individual words and needed a lot of support but I found the real key was the gradual release of responsibility.” [74]

This is consistent with research by Bandura [75] (p. 3), who points out that ‘successes build a robust belief in one’s personal efficacy. Failures undermine it, especially if failures occur before a sense of efficacy is firmly established’. In the course of the intervention, struggling readers experienced success with reading from the outset, through instruction that ranged from teachers modelling the reading process to assisting the student to read independently. Immediately, a high level of engagement among students in the reading process was evident. This engagement appeared to result from a confluence of several factors that can be identified as indicators of an increase in motivation for reading including the level of confidence with which students approached reading. This confidence set the stage for further enhancing students’ motivation for reading. Success begets success, and as students became more motivated to engage in the reading process, they subsequently read more frequently and were more successful in their efforts. Thus, a loop of motivation/success/motivation was created, which accounted for students’ high level of engagement with the FORI intervention.

While the data was collected and analysed separately in the context of reading efficacy, orientation and perceived difficulty, the findings also identified a synergy among these constructs. Analysis of the data from all research informants indicated that motivational behaviour, as interpreted by each construct individually, was also identifiable as a cohesive unit working together to propel students forward. For example, positive effects of FORI on student reading orientation, as defined by students’ interest and engagement in reading, fed into students’ self-efficacy for reading. This in turn had the effect of decreasing students’ perceived difficulty in reading and increased their confidence in reading, which is the factor that directly improves achievement [76].

In this regard, findings indicate that the impact of the FORI intervention on decreasing student’s perceived difficulty with reading was a key factor in establishing the relationship between constructs. Pre-intervention assessment of motivation in relation to this construct indicated that students perceived reading to be a difficult task, had negative attitudes towards reading, and avoided opportunities to read both at school and at home. This was corroborated by data from the assessment of students on the other constructs and was found to impact negatively on students’ orientation towards reading. Post-intervention assessment revealed a significant decrease in students’ perceived reading difficulty as reported by teachers which was supported by evidence from parents. This finding was attributed to the accessibility of reading for students through FORI activities such as choral reading and echo reading in conjunction with methodologies such as repeated reading. As one teacher commented in a review of the effects of FORI six months after the intervention:

“It was like someone unlocked the doors of the reading kingdom for children, turned on the lights and invited them to the party … and they came… and more importantly they stayed.” [77]

One explanation offered by learning support teachers for the decrease in perceived reading difficulty was the gradual release of responsibility model used in the course of the intervention. Some teachers attributed the more favourable ratings on this item to the advantages of using this model, with particular reference to the benefits of modelling reading:

“When you take responsibility and model the reading for the child, you remove the fear of making a mistake. At first I wasn’t totally convinced as I thought that they would just learn it off by heart but modelling the reading was so empowering.” [74]

“When you read for the children first, everybody experiences success at the same time. You could then release the responsibility at different rates with different children … it was real differentiation in action I suppose.” [78]

“Modelling first was the key for me. It was so effective. I recorded myself reading the text fluently and then we would all read with the recording … you know choral reading. Eventually even the weakest readers were reading with intonation. The way I looked at it was if I was teaching someone to bake a cake I would probably demonstrate first and then give assistance after that as I saw fit.” [78].

The ratings of these learning support teachers on students’ orientation towards reading also merit particular mention given these teachers were closest to the process as chief implementers of the FORI intervention. The data from their surveys represents an overall mean increase of 52 percent among students with respect to their reading orientation. The following excerpt from a post-intervention interview with one of these teachers is illuminating in the context of these ratings [77].

- R: The reading orientation ratings for some of your students increased dramatically from pre- to post-intervention. Can you tell me more about this?

- LSC1: These children were selected for the intervention because of their lack of motivation for reading and particularly their low level of interest. They would rarely ever read unless you asked them to and would never ask to bring books home. At free play time it was unlikely that they would ever choose a book as their activity even when we had the star system going for the most books read in a week.

- R: And what happened that changed your opinion?

- LSC1: It was amazing to see the transformation as the intervention went on. They loved the games we played each day and were really competitive. I know that they had to bring the FORI books home every night but they also asked to bring other books as well. One child XXXX was so motivated to improve her time on the word dash activity that she wrote all the words down in her copy to practice them at home …. and the amount they were reading was another dramatic change. It was strange because it wasn’t as if they suddenly became excellent readers. It was that they enjoyed reading and as a result they read more.

The reference here to the increase in the amount of reading by students is representative of findings from all three research sites and is significant in the light of research on intrinsic motivation and reading. The amount that children read influences further growth in reading [79,80,81] and it is documented that students who are intrinsically motivated spend up to three times more time reading than students who have low intrinsic motivation for reading [50]. This is because intrinsically motivated students are more likely to choose to read [37].

The findings relating to the effects of FORI on the motivation for reading also identified some limitations of its efficacy. It was found in the course of the intervention that students’ motivation for reading was influenced very strongly by the degree to which they perceived reading to be difficult. Teachers reported that a student’s confidence in his or her reading ability was often diminished when confronted with text that was too difficult. This was particularly relevant where students continued to have significant difficulties with decoding. Findings thus suggest that FORI strategies may not be effective for students who hold high levels of perceived difficulty in reading unless measures are taken to specifically improve their basic decoding skills. It was found that when students improved in this regard, their perceived difficulty with reading was lessened and they were more likely to regain confidence and to be oriented towards reading. Focusing on decreasing levels of perceived difficulty may help these students improve in reading more than focusing on increasing their interest in reading.

4.1. Role of Parents

An important finding in this study was the positive role parents played in motivating their children to read. The manner in which they responded to their children was identified by teachers as a critical factor in increasing motivation for reading among students. Many reading initiatives fail because the role of parents as a critical component of the literacy process is overlooked by the school environment [82]. Parents play a central role in determining a student’s success at school and have a particularly important role in orienting children towards reading [83]. As part of the FORI intervention, parents were required to read with their child each night, and to sign a home reading log. They were also invited to attend ‘reading with your child’ sessions organised by teachers. To facilitate this requirement, teachers met with parents and provided specific advice on what to read with their children, how much to read, how long to read, how to respond to mistakes, and how to keep the experience enjoyable [84]. This social aspect of reading was highlighted, in interviews with parents and teachers, as being a significant factor in motivating students to read. Teachers were unanimous in acknowledging the important role that parents played in the improvement in reading orientation in particular among students over the course of the study. They reported that the parents’ part in the FORI programme was ‘invaluable in motivating the young struggling readers’ [74] and ‘paid rich dividends when it came to rating children’s orientation for reading’ [77].

The findings have implications for the role that parents play in motivating struggling readers. They converge in suggesting that children who experience literacy-relevant activities at home, view reading more positively, engage in more leisure reading, and have higher motivation for reading.

4.2. Practical Implications

While a single study such as this one cannot provide exclusive guidelines on the ways to improve reading instruction for struggling readers, there are some practical implications for teachers that can be learned. The study has found that there is a relationship between fluency oriented reading instruction and motivation for reading. Without recognition of this critical relationship, teachers and particularly learning support teachers may miss out on instructional methods that addresses students’ reading deficits and that can enhance their enjoyment of reading. Instructional approaches that do not consider motivational strategies for reading, may not capitalise on the added influence that improving students’ motivation for reading has on their long term development as skilled readers. Hence, instruction for struggling readers should be designed in a way that addresses their motivation for reading while simultaneously developing core reading skills.

There are also potential implications for the practice of classroom teachers in primary schools emanating from this study. Findings suggest that practitioners interested in maximising reading achievement among all students should include motivational components in their literacy teaching [85]. The FORI strategies employed in this study are not exclusively designed for the learning support class. Techniques and activities such as choral reading, echo-reading, reader’s theatre and antiphonal reading are readily transferrable to the mainstream classroom. In this regard, the study demonstrates that promoting oral reading fluency among students is an imperative responsibility for all teachers of reading.

4.3. Limitations

There were limitations to this research that require acknowledgement. This is a relatively small-scale project that involved fifteen students from three schools. A larger sample would be more sensitive to possible effect differences in reading motivation among students with particular reading difficulties. Secondly, since the result of this study are based on a limited sample composed of students from schools designated as educationally disadvantaged, care should be taken in over-generalising results. Teachers and students in these intervention schools were operating under more challenging conditions than may be found in other less disadvantaged communities and so the findings from this study may not have the same implications in other schools. Finally, the study was conducted intentionally with struggling readers in First Class because of the critical period this age represents in a student’s reading development. Therefore, we must be careful not to over-generalise the results to primary school students in more senior classes.

4.4. Recommendations for future research

Research has documented that primary schools include large numbers of alliterate students who are capable readers but choose not to read [86]. Given the positive influence of FORI in this study in increasing students’ orientation towards reading and interest in reading, there is a need for further research studies that explore the effects of FORI on these students. In other words, enhancing reading motivation should be a concern not only for struggling readers but for all readers.

Additional research featuring a population that differs from the student population in this study is also recommended. This study was conducted in schools comprised of students predominantly from disadvantaged backgrounds. Future research needs to be conducted with struggling readers in schools from non-DEIS backgrounds. These studies would need to include a no-treatment group so specific fluency-building procedures could be contrasted with a control group and contrasted against each other.

There is also a need for longitudinal research that examines the impact of fluency oriented reading instruction on the motivation for reading of different types of readers at different points along the age continuum. Longitudinal studies of the impact of these procedures could clarify how long the intervention benefits can be maintained.

5. Conclusions

This study set out to explore the effects of fluency oriented reading instruction on motivation among struggling readers in First Class in Irish primary schools. The findings suggest that reading difficulties for these emergent readers are far from insurmountable. However, the current practice of learning support teachers in teaching struggling readers is disproportionally focused on a bottom–up approach to reading instruction rather than on affective processes. In order for struggling readers to overcome skill deficiencies in reading and to be motivated to continue to read, it is imperative that any negative achievement-related self-beliefs are simultaneously addressed.

To achieve this, there needs to be a shift from a purely cognitive interpretation of reading instruction to a motivational and emotional co-determination of beginning reading skills. A conception of compensatory education for students with reading difficulties would thus embrace the engagement perspective while integrating cognitive, motivational, and social aspects of reading. The fluency oriented reading instruction employed in this study aligns with this conception and has been found to positively influence the motivation for reading of young struggling readers in this study.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Acknowledgments

The author is indebted to the teachers and parents who generously gave their time to participate in this research. Additionally, I would like to acknowledge the role played by the students who participated in this study. They embraced each activity with gusto and kept the intervention afloat on a tide of enthusiasm.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest

References and Notes

- OECD. Skills Matter: Results from the Survey of Adult Skills, OECD Skills Studies; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiel, G.; Kelleher, C.; McKeown, C.; Denner, S. Future ready? The Performance of 15-Year-Olds in Ireland on Science, Reading Literacy and Mathematics in PISA 2015; Educational Research Centre: Dublin, Ireland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Education and Science (DES). Special Educational Needs: A Continuum of Support; The Stationery Office: Dublin, Ireland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Eurydice. Teaching Reading in Europe: Contexts, Policies and Practices; Education, Audiovisual and Cultural Executive Agency: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Allington, R.L. What Really Matters for Struggling Readers: Designing Research-Based Programs, 3rd ed.; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, R.T.; McAtee, R. Turning a new page to life and literacy. J. Adolesc. Adult Lit. 2003, 46, 476–481. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, M.; McElvany, N.; Kortenbruck, M. Intrinsic and extrinsic reading motivation as predictors of reading literacy: A longitudinal study. J. Educ. Psychol. 2010, 102, 773–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGeown, S.P.; Osborne, C.; Warhurst, A.; Norgate, R.; Duncan, L.G. Understanding children’s reading activities: Reading motivation, skill and child characteristics as predictors. J. Res. Read. 2016, 39, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigfield, A.; Guthrie, J.T. Relations of children’s motivation for reading to the amount and breadth of their reading. J. Educ. Psychol. 1997, 89, 420–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petscher, Y. A meta-analysis of the relationship between student attitudes towards reading and achievement in reading. J. Res. Read. 2010, 33, 335–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nag, S.; Vagh, S.B.; Dulay, K.M.; Snowling, M.J. Home literacy, school Language and children literacy attainments: A systematic review of evidence from low- and middle-income countries. Rev. Educ. 2019, 7, 91–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poskiparta, E.; Niemi, P.; Lepola, J.; Ahtola, A.; Laine, P. Motivational-emotional vulnerability and difficulties in learning to read and spell. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2003, 73, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral-Marquez, C. Motivating Readers: Helping students set and attain personal reading goals. Read. Teach. 2015, 68, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmunds, K.M.; Bauserman, K.L. International Reading Association. What Teachers Can Learn about Reading Motivation through Conversations with Children. Read. Teach. 2006, 59, 414–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, S.A.; Heubach, K.M.; Cramond, B. Fluency-Oriented Reading Instruction; (Research Report No. 79); National Reading Research Center, University of Georgia and University of Maryland: Athens, GA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, J.; Schwanenflugel, P.J. A longitudinal study of the development of reading prosody as a dimension of oral reading fluency in early elementary school children. Read. Res. Q. 2008, 43, 336–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Early Reading Expert Panel. A Guide to Effective Instruction in Reading: Kindergarten to Grade 3; Ministry of Education: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2003.

- Rasinski, T.V. Creating Fluent Readers. Educ. Leadersh. 2004, 61, 46–51. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, M. Be a good detective: Solve the case of oral reading fluency. Read. Teach. 2000, 53, 534–539. [Google Scholar]

- National Reading Panel. Teaching Children to Read: An Evidence Based Assessment of the Scientific Research Literature on Reading and its Implications for Reading Instruction; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, US Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Osborn, J.; Lehr, F.; Hiebert, E. A Focus on Fluency; Pacific Resources for Education and Learning: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kamil, M.L.; Pearson, P.D.; Moje, E.B.; Afflerbach, P.P. Handbook of Reading Research; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2011; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, M.R.; Stahl, S.A. Fluency: A review of developmental and remedial strategies. J. Educ. Psychol. 2003, 95, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center, Y. Beginning Reading: A Balanced Approach to Reading Instruction in the First Three Years at School; Allen & Unwin: Sydney, Australia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Neuman, S.; Dickinson, D. (Eds.) Handbook of Early Literacy Research; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Paris, S.G. Developmental differences in early reading skills. In Handbook of Early Literacy Research; Neuman, S., Dickinson, D., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; Volume 3, pp. 228–241. [Google Scholar]

- Samuels, S.J. Reading fluency: Its development and assessment. In What Research Has to Say about Reading Instruction, 3rd ed.; Farstrup, A.E., Samuels, S.J., Eds.; International Reading Association: Newark, DE, USA, 2002; pp. 166–183. [Google Scholar]

- Stahl, S.A.; Heubach, K.M. Fluency-oriented reading instruction. J. Lit. Res. 2005, 37, 25–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwanenflugel, P.J.; Hamilton, A.M.; Kuhn, M.R.; Wisenbaker, J.M.; Stahl, S.A. Becoming a fluent reader: Reading skill and prosodic features in the oral reading of young readers. J. Educ. Psychol. 2004, 96, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, J.; Schwanenflugel, P.J. Prosody of syntactically complex sentences in the oral reading of young children. J. Educ. Psychol. 2006, 98, 839–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhn, M.R.; Stahl, S.A. Fluency: A review of developmental and remedial practices. In Theoretical Models and Processes of Reading, 5th ed.; Ruddell, R.B., Unrau, N.J., Eds.; International Reading Association: Newark, DE, USA, 2004; pp. 412–453. [Google Scholar]

- Duke, N.K.; Pressley, M.; Hilden, K. Difficulties in reading comprehension. In Handbook of Language and Literacy; Development and Disorders; Stone, C.A., Silliman, E.R., Ehren, B.J., Apel, K., Eds.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 501–520. [Google Scholar]

- Samuels, S.J.; Farstrup, A.E. What Research Has to Say about Reading Instruction, 4th ed.; International Reading Association: Newark, DE, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Samuels, S.J. The method of repeated readings. Read. Teach. 1979, 32, 403–408. [Google Scholar]

- Gambrell, L.B. Motivation in the School Reading Curriculum. J. Read. Educ. 2011, 37, 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, L.; Wigfield, A. Dimensions of children’s motivation for reading and their relations to reading activity and reading achievement. Read. Res. Q. 1999, 34, 452–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, J.T.; Coddington, C.S. Reading motivation. In Handbook of Motivation at School; Wentzel, K.R., Wigfield, A., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 503–525. [Google Scholar]

- Wigfield, A.; Eccles, J.S.; Rodriguez, D. The development of children’s motivation in school contexts. In Review of Research in Education 23; Iran-Nejad, A., Pearson, P.D., Eds.; American Educational Research Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1998; pp. 73–118. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, B.M.; Codling, R.M.; Gambrell, L.B. In their own words: What elementary students have to say about motivation to read. Read. Teach. 1994, 48, 176–178. [Google Scholar]

- Gambrell, L.B.; Malloy, J.A.; Mazzoni, S.A. Evidenced based practices for comprehensive literacy instruction. In Best Practices in Literacy Instruction; Gambrell, L.B., Morrow, L.M., Pressley, M., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 11–29. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, L.P.; Fuchs, D. Is there a bidirectional relationship between childrens’ reading skills and reading motivation? Except. Child. 2007, 73, 165–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweet, A.P.; Guthrie, J.T.; Ng, M. Teachers’ perceptions and students’ reading motivations. J. Educ. Psychol. 1998, 90, 210–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coddington, S.C.; Guthrie, T.J. Teacher and student perceptions of boys’ and girls’ reading motivation. Read. Psychol. 2009, 30, 225–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, J.W.; Tunmer, W.E.; Prochnow, J.E. Early reading-related skills and performance, reading self-concept, and the development of academic self-concept: A longitudinal study. J. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 92, 703–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, K.B.; Marshall, T.R.; Wray, E. A longitudinal study of the role of reading motivation in primary students’ reading comprehension: Implications for a less simple view of reading. Read. Psychol. 2016, 37, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirk, M.; Schwanenflugel, P.J.; Webb, M. A Short-Term Longitudinal Study of the Relationship between Motivation to Read and Reading Fluency Skill in Second Grade. J. Lit. Res. JLR 2009, 41, 196–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, J.T.; Anderson, E. Engagement in reading: Processes of motivated, strategic, knowledgeable, social readers. In Engaged Reading: Processes, Practices, and Policy Implications; Guthrie, J.T., Alvermann, D.E., Eds.; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 17–45. [Google Scholar]

- Oldfather, P.; Wigfield, A. Children’s motivations to read. In Developing Engaged Readers in School and Home Communities; Baker, L., Afflerbach, P., Reinking, D., Eds.; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1996; pp. 89–113. [Google Scholar]

- Wigfield, A.; Wilde, K.; Baker, L.; Fernandez-Fein, S.; Scher, D. The Nature of Children’s Reading Motivations, and Their Relations to Reading Fluency and Reading Performance; National Reading Research Center: Athens, GA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Wigfield, A.; Guthrie, J.T. Motivation for reading: Individual, home, textual, and classroom perspective. Educ. Psychol. 1997, 32, 57–135. [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie, J.T.; Humenick, N.M. Motivating students to read: Evidence for classroom practices that increase reading motivation and achievement. In The Voice of Evidence in Reading Research; McCardle, P., Chhabra, V., Eds.; Brookes Publishing: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2004; pp. 329–354. [Google Scholar]

- Aunola, K.; Leskinen, E.; Onatsu-Arvilommi, T.; Nurmi, J.E. Three methods for studying developmental change: A case of reading skills and self-concept. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2002, 72, 343–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, J.W.; Tunmer, W.E. Reading difficulties, reading-related self-perceptions, and strategies for overcoming negative self-beliefs. Read. Writ. Q. Overcoming Learn. Diffic. 2003, 19, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepola, J.; Poskiparta, E.; Laakkonen, E.; Niemi, P. Developmental Interaction of Phonological and Motivational Processes and Naming Speed in Predicting Word Recognition in Grade 1. Sci. Stud. Read. 2005, 9, 365–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sideridis, G.D.; Morgan, P.L.; Botsas, G.; Padeliadu, S.; Fuchs, D. Identification of students with learning difficulties based on motivation, metacognition, and psychopathology: A ROC analysis. J. Learning Disabil. 2006, 39, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, J.W. Learning disabled children’s self-concepts. Rev. Educ. Res. 1998, 58, 347–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanovich, P.J.; Jordan, A.; Perot, J. Relative differences in academic self-concept and peer acceptance among students in inclusive classrooms. Remedial Spec. Educ. 1998, 19, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulk, B.M.; Brigham, F.J.; Lohman, D.A. (Eds.) Motivation and self-regulation: A comparison of students with learning and behaviour problems. Remedial Spec. Educ. 1998, 19, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malloy, J.A.; Marinak, B.A.; Gambrell, L.B. (Eds.) Essential Readings in Motivation; International Reading Association: Newark, DE, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Salonen, P.; Lepola, J.; Niemi, P. The development of first graders’ reading skill as a function of pre-school motivational orientation and phonemic awareness. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 1998, 13, 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.M.; Manset-Williamson, G. The impact of explicit, self-regulatory reading comprehension strategy instruction on the reading-specific self-efficacy attributions, and affect of students with reading disabilities. Learn. Disabil. Q. 2006, 29, 213–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, J.T.; Wigfield, A.; Metsala, J.L.; Cox, K.E. Motivational and cognitive predictors of text comprehension and reading amount. Sci. Stud. Read. 1999, 3, 231–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintrich, P.R. Multiple goals, multiple pathways: The role of goal orientation in learning and achievement. J. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 92, 544–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J.; Adler, T.F.; Futterman, R.; Goff, S.B.; Kaczala, C.M.; Meece, J.; Midgley, C. Expectancies, values and academic behaviours. In Achievement and Achievement Motives; Spence, J.T., Ed.; W.H. Freeman: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie, J.T.; Coddington, C.S.; Wigfield, A. Profiles of reading motivation among African American and Caucasian students. J. Lit. Res. 2009, 41, 317–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzoni, S.A.; Gambrell, L.B.; Korkeamaki, R.L. A cross-cultural perspective of early literacy motivation. J. Read. Psychol. 1999, 20, 237–253. [Google Scholar]

- Wigfield, A.; Guthrie, J.T.; McGough, K. A Questionnaire Measure of Children’s Motivations for Reading; National Reading Research Center: Athens, GA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, M.R.; Schwanenflugel, P.J. Fluency in the Classroom. The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Schwanenflugel, P.J.; Kuhn, M.R.; Morris, R.D.; Morrow, L.M.; Meisinger, E.B.; Woo, D.G.; Quirk, M.; Sevcik, R. Insights into fluency instruction: Short- and long-term effects of two reading programs. Lit. Res. Instr. 2009, 48, 318–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehigan, G. Oral reading fluency: A link from word reading efficiency to comprehension. In From Literacy Research to Classroom Practice: Insights and Inspiration; Willoughby, K., Culligan, B., Kelly, A., Mehigan, G., Eds.; Reading Association of Ireland: Dublin, Ireland, 2012; pp. 99–113. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, J.W.; Tunmer, W.E. Development of young children’s reading self-concepts: An examination of emerging subcomponents and their relationship with reading achievement. J. Educ. Psychol. 1995, 87, 154–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, L.M.; Asbury, E. Current practices in early literacy development. In Best Practices in Literacy Instruction; Morrow, L.M., Gambrell, L.B., Pressley, M., Eds.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2003; Volume 2, pp. 43–63. [Google Scholar]

- Optiz, M.F.; Rasinski, T.V. Good-Bye Round Robin Reading: 25 Effective Oral Reading Strategies; Heinemann: Portsmouth, NH, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Field notes of interview with learning support teacher in School A.

- Bandura, A. (Ed.) Exercise of personal and collective efficacy in changing societies. In Self-Efficacy in Changing Societies; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995; pp. 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Cambria, J.; Guthrie, J.T. Motivating and Engaging Students in Reading. N. Engl. Read. Assoc. J. 2010, 46, 16–29. [Google Scholar]

- Field notes of interview with learning support teacher in School C.

- Field notes of interview with learning support teacher in School B.

- Baker, L.; Dreher, M.J.; Guthrie, J.T. (Eds.) Engaging Young Readers: Promoting Achievement and Motivation; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Stanovich, K.E.; West, R.F.; Cunningham, A.E.; Cipielewski, J.; Siddiqui, S. The role of inadequate print exposure as a determinant of reading comprehension problems. In Reading Comprehension Difficulties: Processes and Interventions; Cornoldi, C., Oakhill, J., Eds.; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1996; pp. 15–32. [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie, J.T.; Wigfield, A. Engagement and motivation in reading. In Reading Research Handbook; Kamil, M.L., Mosenthal, P.B., Pearson, P.D., Barr, R., Eds.; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2000; Volume 3, pp. 403–424. [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenschein, S.; Baker, L.; Serpell, R.; Schmidt, D. Reading is a source of entertainment: The importance of the home perspective for children’s literacy development. In Play and Literacy in Early Childhood: Research from Multiple Perspectives; Roskos, K.A., Christie, J.F., Eds.; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2000; pp. 125–137. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, L.; Serpell, R.; Sonnenschein, S. Opportunities for literacy learning in the homes of urban preschoolers. In Family Literacy: Connections in Schools and Communities; Morrow, L.M., Ed.; International Reading Association: Newark, DE, USA, 1995; pp. 236–252. [Google Scholar]

- Ollila, L.O.; Mayfield, M.I. Home and school together: Helping beginning readers succeed. In What Research Has to Say about Reading Instruction; Samuels, S.J., Farstrup, A.E., Eds.; International Reading Association: Newark, DE, USA, 1992; pp. 17–45. [Google Scholar]

- Afflerbach, P.; Cho, B.Y. The classroom assessment of reading. In Handbook of Reading Research; Kamil, M.L., Pearson, P.D., Moje, E.B., Afflerbach, P.P., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2011; Volume 4, pp. 478–541. [Google Scholar]

- Agee, J. Literacy, aliteracy, and lifelong learning. New Libr. World 2005, 106, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).