Abstract

The current study reports on a reading intervention method titled Read Like Me. The intervention utilizes a stacked approach of research-based methods, including reading aloud, assisted reading, and repeated reading. The student involved was a second-grade boy reading below grade level who was identified as dyslexic and diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactive disorder. Using a single-case experimental design, the intervention was monitored in four phases, including a baseline, intervention coupled with regular schooling, intervention only, and a return to baseline. The results indicated that the intervention combined with regular schooling improved his reading expression and rate and also his decoding skills, word knowledge, and reading comprehension. In conclusion, the authors offer Read Like Me as one more intervention that may be a viable option for teachers in their effort to support developing readers.

1. Read Like Me: An Intervention for Struggling Readers

The theory of automaticity essentially purported that the more automatic readers become in word recognition, the more cognitive resources can be reallocated to higher-level reading processes, such as reading comprehension [1]. Stanovich [2] referred to the theory of automaticity as a critical precursor to many important reading theory developments. Decades later, it is still used to frame studies in reading, especially those that examine practiced-based methods [3,4,5,6]. The purpose of this study was to explore the effectiveness of a newly developed practice-based reading intervention for struggling elementary readers. The intervention, Read Like Me, is a multifaceted approach comprised of several researched interventions, including reading aloud, repeated readings, assisted reading, and the gradual release of responsibility. In light of the significant impact that the methods have on students’ reading, the methods were combined to create a synergistic and potentially effective intervention.

Struggling readers need expert, research-based instruction [7] especially as the expectations grow for young readers. Students are increasingly required to read texts that are too difficult, a requirement that contradicts previous research [8,9]. Gradually, however, that perspective has changed [10], and students are frequently engaged in texts that are far more challenging. Allington [7] adamantly opposes this practice and reminds us that adults would likely refuse to read books at only 98%-word recognition accuracy, which would amount to approximately six unknown words per page. Regardless, here we are putting difficult texts into the hands of struggling readers.

Recently, Strong, Amendum, and Conradi Smith [11] described a similarly dim outlook on the current perspectives on text difficulty in modern reading education. However, the authors continued on to describe some of the research that may help educators consider the appropriate contexts for utilizing challenging texts. Before selecting a text, a teacher should consider the reader and also how much assistance will be provided. Thus, it might be possible for teachers to use difficult texts when administering interventions that provide sufficient supports for the reader.

Read Two Impress (R2I) [12] is an example of an intervention that calls for challenging texts, within approximately one year of the students’ independent reading level. R2I is a hybrid of repeated readings [13] and the neurological impress method [14], both highly assistive methods for reading intervention. Read Two Impress has had large effects on students’ reading fluency [15] reading comprehension [16] and independent reading level [17].

Young, Mohr, and Rasinski [15] claimed that the texts, however, were not frustrational, necessarily, but, rather, on the outer limits of the students’ zone of proximal development [18] That is, adequate scaffolds were applied, and the students were able to engage in successful reading. Furthermore, texts were modeled and then practiced, essentially following the tenets of the gradual release of responsibility [19]. Thus, in this case, the higher-level texts did not impede their reading growth but, rather, enhanced it. Similarly, researchers have found challenging texts optimal when engaging in close reading protocols [10]. Read Two Impress has had similar success with challenging text since its inception and first use with a third-grade boy named, Emilio (pseudonym).

Emilio started something back in 2009, though his story was not told until 2012 by Mohr, Dixon, and Young. He was a struggling third grader who did not respond to multiple reading interventions and intense guided reading instruction in the classroom. He was approaching a place where students rarely catch their peers in reading—the rich were getting richer, and Emilio was getting poorer [20].

The reading specialist then did some research and presented a few potential interventions to the students. Emilio chose repeated readings [13]. After several weeks, his reading rate and comprehension had improved, and his stagnant reading level shifted positively for the first time in a long while. However, he still read in a monotone voice and appeared to not enjoy reading, despite his progress. Because of his improvement, the reading specialist was hesitant to remove repeated readings as an intervention, and so, it was decided to add neurological impress [14] to improve his reading prosody. The methods were combined and appeared to have a synergistic effect on Emilio’s reading. By the end of the ten-week intervention, Emilio was reading at grade level with adequate reading fluency and comprehension.

In addition, Emilio showed an interest in reading and claimed his favorite author was Jeff Kinney. This was important because he had no favorite authors or books at the beginning of the intervention [21]. It seemed that he was motivated by his progress, which is why the current study added an additional component to the R2I protocol, reading aloud. While R2I has been used successfully with struggling readers, it seemed there were two missing pieces, including a complete modeling of the text and an opportunity for the student to read the text aloud as a whole.

The genesis of Read Like Me resulted from the promising results of R2I, and while the method improved reading fluency and comprehension, it failed to improve students’ attitude [16]. It was decided that the method, while powerful, lacked authenticity. Students were not given the opportunity to read the text as a whole and feel the success of reading a challenging text from beginning to end. Therefore, the researchers added a few other elements, a concept often used with struggling readers typically referred to as “stacked instruction”. This approach takes multiple research-based interventions and stacks them to work in a more synergistic and powerful way [21].

Thus, the researchers framed Read Like Me based on a whole-part-whole instructional process in the hopes of adding authenticity while simultaneously stacking instruction. In Read Like Me, the tutor reads the entire text aloud and entertains the student with a prosodic read aloud, then the tutor and student use R2I to assist the student in developing mastery of the text, and finally, the student reads the entire text aloud—in the end, the student engages in successful authentic reading.

2. The Benefits of Reading Aloud

Reading aloud is one way to model how words printed on a page are converted into oral language with all of the variables of timing, phrasing, intonation, and emphasis (prosody) that speakers use. More simply, reading aloud models how the written word becomes the spoken word. The effects of good read alouds on literacy learning have been supported in the literature for many years [22,23,24,25]. These include fostering vocabulary growth [26,27], developing listening comprehension [28,29] and expanding an understanding of good sentence and story structure [30,31].

Beyond the cognitive benefits of read alouds (and perhaps more importantly) is the impact on affective factors. Choosing to read is determined by attitude and desire [32,33]. Reading aloud positively influences the attitudes of children toward reading and motivates them to want to read [23,34]. Hearing a story read in its entirety, being swept away by the words and the images they create, and experiencing the power of language to cause one to laugh or cry or wonder or hold your breath—all encourage youngsters to want more and, eventually, to be able to read it themselves. Having good models that bring text alive through the natural rhythm and beauty of language, encourages children to want to read just like that.

In Read Like Me, the interventionist begins the session with a powerful read aloud, allowing the child to hear the text in its entirety. Modeling the way language works to create vivid pictures of story, pulls the child into the text right from the start. As the text is revisited in smaller sections (using the impress method), the child is encouraged to use the same timing, phrasing, intonation, and emphasis. At the conclusion of the session, the child reads the whole book back.

As we know from years of research, perception of self as a reader, an affective factor, is an important determinate in reading success [35,36,37]. Using this intervention, Read Like Me, encourages children to see (and hear) themselves as good readers.

3. Significance of the Study

Early literacy was considered a hot topic and deemed the most important in the 2018 What’s Hot What’s Not survey [38]. Reading research has been conducted for centuries, but yet, there is still a need for additional reading interventions, as no one intervention will work for every student. Thus, teachers need access to a plethora of options to support young readers who find the process difficult. This research aimed to describe a newly developed option for reading intervention and to track the growth of a second-grade student who has difficulty reading for a variety of reasons. The research was guided by the following research question: What are the effects of Read Like Me as a supplemental and a standalone intervention for a second-grade student who struggles with reading?

4. Method

4.1. The Participant and the Interventionist

The participant in the experiment was a second-grade student (8 years old) at the time the intervention took place. The student received services under Section 504 for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and dyslexia. According to the American Psychiatry Association, ADHD is characterized by inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity—symptoms that arguably have a negative effect on one’s ability to focus on reading. Dyslexia, defined in the American Disabilities Act, is a neurobiological disorder that results in an unexpected difficulty learning to read and write.

The student was nearly two years below grade level in reading prior to the intervention. He lacked confidence in reading but loved science. The participant was an active student and enjoyed discussion of any topic. It was important to serve this need during the experiment to maintain student focus during the intervention.

The interventionist for this experiment was a senior-level, undergraduate, pre-service teacher. The interventionist had training in the ethics of research prior to the conducted experiment. A lack of training undermines and potentially inhibits the success of both the intervention and the student’s progress. The interventionist also had experience and training in components of the intervention including, but not limited to, tracking progress, collecting data, and selecting reading materials according to student needs. This provided the interventionist with background knowledge to ensure that accurate and appropriate measures were taken during the experiment. In addition, the interventionist had previously administered Read Like Me to a second-grade student for 700 minutes prior to the study.

4.2. Procedures

The purpose of this study was to explore the effectiveness of a newly developed reading intervention for struggling elementary readers. The intervention, Read Like Me, is a multifaceted approach composed of several researched interventions. The researchers employed the timeless practice of reading aloud [39] at the beginning of the intervention, followed by a practice-based method called Read Two Impress [12]. After sufficient practice, the student then read the text aloud to the interventionist. In this study, the student received the intervention three times per week for 12 weeks. The following are the steps used in each thirty-minute session:

- Choose a challenging text (approximately six months above the student’s reading level);

- Read the entire text aloud with appropriate expression while the student listens;

- Go back to the beginning and read a page or paragraph aloud together;

- Read slightly ahead of the student;

- Read with good expression that matches the meaning of the text;

- Have the student reread each page/paragraph aloud;

- Continue with subsequent page/paragraphs until the text is complete;

- Have the student read the book aloud as you did in the beginning (Read Like Me).

The intervention was given three days a week for 30 min each day and was conducted similarly during each session. To begin, the interventionist reads a book that is approximately six months above the student’s current independent reading level. If the text appears to be too difficult after following the Read Like Me protocol, dropping a level may be necessary. Conversely, levels can be increased if the student reads with ease. In this particular case, the chosen books increased by one level each week. However, it remains a case-by-case decision. It is important for the interventionist to read the book with the exact expression and fluency with which they want the student to read.

After reading the book, the interventionist and student reread it together using the R2I protocol. The interventionist starts off and reads at a pace that is comfortable for the student but still challenges their normal pace. The goal is to push them to reach their full potential without overwhelming or frustrating them. Hence, the interventionist sets the pace with the particular student in mind. This phase is done page by page. Once the page is read together, the student then reads the page himself to the interventionist. This continues until the book is finished or the reading for that day is completed.

The third and final phase of the intervention is done solely by the student. The student starts from the beginning of the book and now reads aloud to the interventionist on his own. The interventionist assists as needed on major miscues but allows the student as much independence in this phase as possible. This is the phase that builds the student’s confidence. The third phase completes the session for that day. It is important that the interventionist monitors the progress of the student throughout the treatment phase so that the levels of the books chosen are appropriate. This process continues for each session—three times a week for 30 min—for a minimum of 12 weeks. Following the twelve-week mark, data were reviewed and graphed to determine the results, and post assessments were administered to see if the progress remained or dissipated once the intervention ceased.

4.3. Design and Instrumentation

To complete the preliminary investigation, we planned a single-subject experimental ABCA design, meaning we established a baseline (A), introduced an intervention (B), modified the intervention (C), and returned to baseline (A). We used leveled reading passages to establish a baseline, monitor two treatment phases, and then returned to the baseline. For leveled passages, we used the Grade 2 Oral Reading Fluency passages from Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills (DIBELS-ORF) [40]. The weekly administration of DIBELS-ORF provided a word recognition automaticity score (words read correctly per minute). During the oral reading, we also scored the student’s reading prosody with the Multidimensional Fluency Scale (MDFS) [41]. Scores were independently reviewed to establish inter-rater reliability, and the resulting measure of agreement was considered outstanding (Kappa = 0.93, p < 0.001).

In addition, the primary researcher administered the Gates MacGinitie Reading Test (4th Edition) for second grade (GMRT-4) before and after the intervention phases. The GMRT-4 is a standardized reading assessment that measures a student’s reading comprehension, word knowledge, and decoding. Validity and reliability of the GMRT-4 is considered high. The correlations between the two forms (S for the pretest and T for the posttest) are strong on all three measures, including word decoding (r = 0.86), word knowledge (r = 0.86), and reading comprehension (r = 0.82). The overall scores between the forms are also strongly correlated (r = 0.90). Finally, the internal consistency and reliability is also considered high (KR-20 = 0.97; [42]).

5. Results

The entire study lasted for 21 weeks. The first five weeks was spent establishing a baseline using the DIBELS-ORF passages, and the student regularly attended school. The first treatment phase lasted six weeks and was comprised of regular schooling and after school Read Like Me tutoring. Neither DIBELS-ORF nor the MDFS was administered during the first week of tutoring, as the student was assessed at the end of the week prior by the primary researcher. The second treatment phase lasted six weeks and only included the Read Like Me tutoring because of the year-round school’s summer break. Overall the student engaged in Read Like Me tutoring for approximately 1080 minutes. Once the child resumed regular schooling, the tutoring was removed, and the student was assessed once per week to reestablish a baseline. The student also took the GMRT-4 the week before (form S) and after (form T) the intervention phase.

5.1. Word Recognition Automaticity

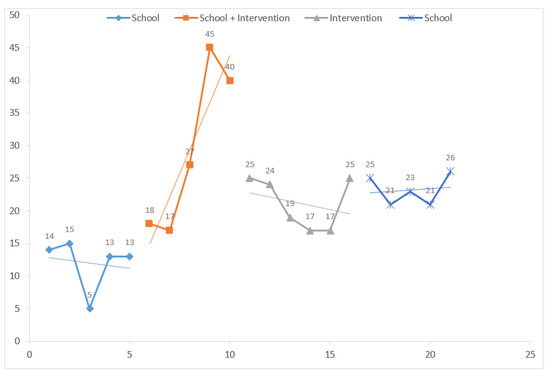

The initial baseline revealed, on average, that the student read around 12 words correctly per minute, and there appeared to be a slight downward trend (Figure 1). The student’s baseline was not perfectly stable because of one slight anomaly (test 3) where the student performed below normal. However, the remaining four assessments were quite consistent (14, 15, 13, 13). With this in mind, the researchers agreed that an adequate baseline was established.

Figure 1.

Weekly word recognition automaticity scores based on Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills (DIBELS-ORF).

During the school + intervention phase, there was an apparent steep positive trend. At the onset, the student read between 17 and 18 words correctly per minute, but after a few weeks, the student’s score was in the 40s. Conversely, during the intervention phase without regular schooling, the researchers observed a dip and another slight downward trend. However, on average, the student was still performing better (21 Words Read Correctly Per Minute; WCPM) than the baseline (12 WCPM). Finally, the baseline was reestablished and was considered relatively stable around 23 WCPM.

5.2. Reading Prosody

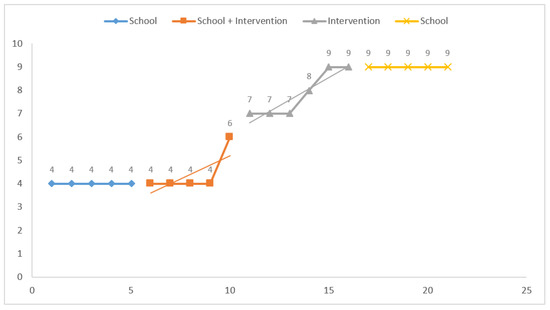

The initial baseline was stable, and the student was consistently rated a four using the MDFS rubric (Figure 2). During the school + intervention phrase, the student was rated a four until the final week, when he was rated at a level six. As can be seen in the next intervention phase, the student continued to grow in reading prosody, achieving a rating of nine the final two weeks. When the intervention was removed and school resumed, the student remained a nine but showed no further growth in reading prosody.

Figure 2.

Weekly prosody scores based on the Multidimensional Fluency Scale (MDFS).

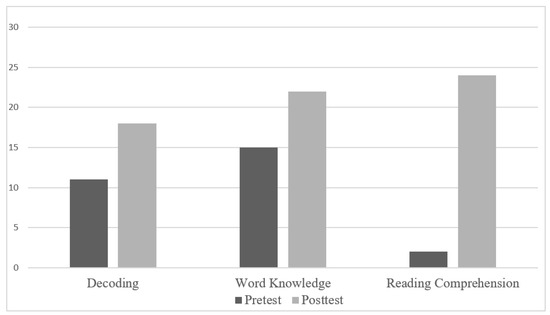

5.3. Decoding, Word Knowledge, and Reading Comprehension

Due to the length of the GMRT-4, and the limited forms, the assessment was not used in a single-subject experimental manner. Instead, the GMRT-4 was administered as a pre- and posttest to obtained standardized scores in order to measure growth of the student’s decoding skills, word knowledge, and reading comprehension. At the onset of the study, the student correctly answered 11 decoding questions, 15 questions in the word knowledge section, and only correctly answered two of the reading comprehension questions. Then, 12 weeks later, after receiving six weeks of school + intervention and intervention only, the student scored higher on all three measures, especially in reading comprehension where he scored 12 times better than before (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Pre- and posttest results from the Gates MacGinitie Reading Test (4th Edition) for second grade (GMRT-4).

6. Discussion

This study examined the effects of two intervention phases on a second-grade student’s reading development, including word recognition automaticity (WCPM), reading prosody (expression), decoding skills, work knowledge, and reading comprehension. Overall, the researchers observed growth on all of the assessments. Thus, Read Like Me might serve other students who have difficulty with reading.

According to the results of the word recognition automaticity and prosody probes, the intervention worked best when paired with regular instruction. The intervention adheres to the gradual release of responsibility method [19], which may serve to increase the student’s ability to quickly recognize words and read at an increased rate. The student first heard the story in its entirety and listened to the words read accurately. The second phase was an assisted reading approach that allowed students to practice alongside a proficient reader and then practice reading the words on their own, receiving feedback or assistance as necessary. In the end, the student has heard the words, read them with assistance, practiced the words, and essentially “performed” an oral reading of the text as a whole. In this case, multiple exposures to the words and the opportunity to learn and practice them served the student well.

It is important to note that continuation of the intervention over the break prevented the typical summer reading slide, where students often lose some of their reading gains [43]. This phenomenon is especially detrimental for struggling readers. It is also important to note that this student’s reading growth was stagnant for much of his second-grade year; therefore, any amount of growth warranted celebration. Albeit slow, Read Like Me successfully promoted, perhaps even kick-started, positive growth in reading rate and prosody.

Prosody has historically been neglected in reading instruction [44,45,46]. In a study [47] that employed reader theater and karaoke as reading activities, students in both the treatment and comparison groups made significant gains in word recognition automaticity, but only the treatment group made gains in reading prosody. The authors claim that this disparity was attributed to the types of instruction. Typical school instruction does, indeed, attend to reading rate but often neglects prosody. Because the interventions in the treatment (reader theater and karaoke) also focused on expressive reading, there was a much greater increase. Several components of Read Like Me focus on prosody. First, the initial read aloud provides a model of fluent and expressive reading [48]. Second, the added neurological impress component has been said to “etch” the interventionist’s prosodic renderings into the mind of the reader [14,49,50], and the immediate repeated reading allows the reader to demonstrate or mimic fluent and expressive reading. Finally, the student is asked to “read like me” and independently reads aloud the text similar to the initial oral reading done by the interventionist. Therefore, increases in reading prosody as a result of the intervention are likely.

When considering the results of the GMRT-4, the student made gains in all three areas tested. There was a 63% (7 points) increase on both the decoding and word knowledge portions of the assessment. In the comprehension section, the student scored 22 points higher, which was a 1100% increase. Clearly the time spent in class and on the intervention did more than help the student become a more fluent reader; it also helped him better understand text by increasing his decoding skills, word knowledge, and most importantly, reading comprehension—which is the main goal of reading.

Previous studies have confirmed that increasing foundational skills, such as decoding and word recognition automaticity, can lead to increased reading comprehension [51,52]. Research has also indicated that systematic instructional protocols can improve students’ reading ability, particularly those with ADHD [53] and dyslexia [54].

The increase in comprehension is also supported by the theoretical framework of this study, indicating that the student’s increased automatic reading freed cognitive resources that could then be allocated to reading comprehension [1]. When considering other theories, admittedly there was less of an emphasis on the transactional nature of reading experiences [55] and more of an emphasis on a previous theoretical understanding of reading, namely the New Criticism literacy theory [56]. The theory promotes intense close readings and focuses on text-dependent comprehension rather than a focus on prior experiences of readers—a strategy that has dominated reading instruction for decades [10]. While Read Like Me did not have an explicit reading comprehension component, the repetitive nature likely helped the reader understand the literal meanings of text. Moreover, the GMRT-4 comprehension section arguably tests student’s ability to understand text more explicitly than implicitly. Thus, the type of instruction used in the intervention closely matched the assessment employed.

7. Limitations and Further Research

Standardized tests are not without limitations, as they are snapshots taken on a single day, and they are not indicative of the precise potential of a student. However, the researchers felt that standardized tests would complement the progress monitoring measures administered throughout the study, as they added specific measures of decoding, word knowledge, and reading comprehension, which were not directly measured during the course of the intervention. Additional research should likely include some form of reading comprehension monitoring throughout the study.

There are inherent limitations in single-case experimental research, most notably the inability to generalize beyond the case. In this case, a second grader diagnosed with ADHD and dyslexia benefited from the intervention. There is no guarantee that Read Like Me will work with every student who struggles with reading, but it does serve as an additional option for teachers and interventionists. A larger experimental or quasi-experimental study with treatment and control groups could further examine the utility and effectiveness of the intervention.

8. Conclusions

Overall, supplementing regular instruction with Read Like Me successfully accelerated the reading development of the second grader involved in the study. The stacked approach increased the student’s word recognition automaticity, reading prosody, decoding skills, word knowledge, and reading comprehension. Although this study cannot be generalized, the results suggest that this may be a viable option for teachers or interventionists working with students who find reading difficult.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Y. and J.M.; methodology, C.Y.; validation, C.Y. and S.L.; formal analysis, C.Y. and S.L.; investigation, C.Y., S.L., and J.M.; resources, C.Y. and S.L.; data curation, S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, C.Y., S.L. and J.M.; writing—review and editing, C.Y., S.L. and J.M.; supervision, C.Y.; project administration, C.Y. and S.L.; funding acquisition, C.Y. and S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by EURECA Center at Sam Houston State University, grant number 29021.

Acknowledgments

We’d like to thank the participant, his family, and his teacher. We appreciate your willingness to try out a new intervention.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- LaBerge, D.; Samuels, S.J. Toward a theory of automatic information processing in reading. Cognit. Psychol. 1974, 6, 293–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanovich, K.E. The impact of automaticity theory. J. Learn. Disabil. 1987, 20, 167–168. [Google Scholar]

- Förster, N.; Kawohl, E.; Souvignier, E. Short- and long-term effects of assessment-based differentiated reading instruction in general education on reading fluency and reading comprehension. Learn. Instr. 2018, 56, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Yoon, S.Y. The Effects of Repeated Reading on Reading Fluency for Students with Reading Disabilities. J. Learn. Disabil. 2016, 50, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roembke, T.C.; Hazeltine, E.; Reed, D.K.; McMurray, B. Automaticity of word recognition is a unique predictor of reading fluency in middle-school students. J. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 111, 314–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadasy, P.F.; Sanders, E.A. Repeated reading intervention: Outcomes and interactions with readers’ skills and classroom instruction. J. Educ. Psychol. 2008, 100, 272–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allington, R.L. What Really Matters When Working With Struggling Readers. Read. Teach. 2013, 66, 520–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clay, M. Becoming Literate: The Construction of Inner Control; Heinemann: Portsmouth, NH, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Leslie, L.; Caldwell, J. Qualitative reading Inventory; Pearson Education, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, D.; Frey, N. Student and Teacher Perspectives on a Close Reading Protocol. Lit. Res. Instr. 2013, 53, 25–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, J.Z.; Amendum, S.; Smith, K.C. Supporting Elementary Students’ Reading of Difficult Texts. Read. Teach. 2018, 72, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, C.; Rasinski, T.; Mohr, K.A.J. Read Two Impress: An intervention for disfluent readers. Read. Teach. 2016, 69, 633–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuels, S.J. The method of repeated readings. Read. Teach. 1979, 41, 756–760. [Google Scholar]

- Heckelman, R. A Neurological-Impress Method of Remedial-Reading Instruction. Acad. Ther. 1969, 4, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, C.; Mohr, K.A.J.; Rasinski, T. Reading together: A successful reading fluency intervention. Lit. Res. Instr. 2015, 54, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, C.; Pearce, D.; Gomez, J.; Christensen, R.; Pletcher, B.; Fleming, K. Examining the effects of Read Two Impress and the Neurological Impress Method. J. Educ. Res. 2018, 111, 657–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, C.; Durham, P.; Rosenbaum-Martinez, C. A Stacked Approach to Reading Intervention: Increasing 2nd- and 3rd-Graders’ Independent Reading Levels With an Intervention Program. J. Res. Child. Educ. 2018, 32, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L.V. Mind in Society; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, M.; Pearson, P.D. The Instruction of Reading Comprehension in Contemporary Educational Psychology; Longman: White Plains, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Stanovich, K.E. Matthew Effects in Reading: Some Consequences of Individual Differences in the Acquisition of Literacy. Read. Res. Q. 1986, 21, 360–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, K.A.; Dixon, K.; Young, C. Effective and Efficient: Maximizing Literacy Assessment and Instruction. Theor. Models Learn. Lit. Dev. 2012, 1, 293–324. [Google Scholar]

- Heath, S.B. Ways with Words: Language, Life and Work in Communities and Classrooms; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Pegg, L.A.; Bartelheim, F.J. Effects of daily read-alouds on students’ sustained silent reading. Curr. Issues Educ. 2011, 14, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins, C.; Ehri, L.C. Reading storybooks to kindergarteners helps them learn new vocabulary words. J. Educ. Psychol. 1994, 86, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulanoff, S.; Pucci, S.L. Learning Words from Books: The Effects of Read-Aloud on Second Language Vocabulary Acquisition. Biling. Res. J. 1999, 23, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allington, R.L.; Cunningham, P.M. Schools that Work: Where All Children Read and Write; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Farrant, B.; Zubrick, S. Early vocabulary development: The importance of joint attention and parent-child book reading. First Lang. 2011, 32, 343–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, L.M.; Brittain, R. The nature of storybook reading in the elementary school: Current practices. In Reading Books to Children: Parents and Teachers; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 95–113. [Google Scholar]

- Opitz, M.; Rasinski, T. Good-Bye Round Robin; Heinemann Educational Books: Portsmouth, NH, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kalb, G.; Van Ours, J.C. Reading to young children: A head-start in life? Econ. Educ. Rev. 2014, 40, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.W.; Elley, W.B. How Children Learn to Read: Insights from the New Zealand Experience; Longman: Auckland, New Zealand, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- McKenna, M.C.; Kear, D.J.; Ellsworth, R.A. Children’s attitudes toward reading: A national survey. Read. Res. Q. 1995, 30, 4934–4956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olufowobi, O.O.; Makinde, S.O. Aliteracy: A threat to educational development. Educ. Res. 2011, 2, 824–827. [Google Scholar]

- Massaro, D.W. Reading Aloud to Children: Benefits and Implications for Acquiring Literacy Before Schooling Begins. Am. J. Psychol. 2017, 130, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, J.E. Enhancing the attitudes of children toward reading: Implications for teachers and principals. Read. Improv. 2002, 39, 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Zolgar-Jerkovic, I.; Jenko, N.; Lipec-Stopar, M. Affective factors and reading achievement in different groups of readers. Int. J. Spec. Educ. 2018, 33, 201–211. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, R.S.; Aricak, O.; Jewell, J. Influence of reading attitude on reading achievement: A test of the temporal-interaction model. Psychol. Sch. 2008, 45, 1010–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Literacy Association. What’s Hot in Literacy 2018 Report; International Literacy Association: Newark, DE, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell, E.J. Listen, My Children, and You Shall Read. Engl. J. 1966, 55, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Good, R.H.; Kaminski, R.A.; Dill, S. (Eds.) DIBELS Oral Reading Fluency. In Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills, 6th ed.; Institute for the Development of Educational Achievement: Eugene, OR, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zutell, J.; Rasinski, T.V. Training teachers to attend to their students’ oral reading fluency. Theory Pract. 1991, 30, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacGinitie, W.H.; MacGinitie, R.K.; Maria, K.; Dreyer, L.G. Gates-MacGinitie Reading Tests—Technical Report (Forms S and T), 4th ed.; Riverside: Rolling Meadows, IL, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Allington, R.L.; McGill-Franzen, A.; Camilli, G.; Williams, L.; Graff, J.; Zeig, J.; Zmach, C.; Nowak, R. Addressing Summer Reading Setback Among Economically Disadvantaged Elementary Students. Read. Psychol. 2010, 31, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowhower, S.L. Speaking of prosody: Fluency’s unattended bedfellow. Theory Pract. 1991, 30, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasinski, T.V. Why fluency should be hot! Read. Teach. 2012, 65, 516–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasinski, T. Is What’s Hot in Reading what should be Important for Reading Instruction? Lit. Res. Instr. 2016, 55, 134–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, C.; Valadez, C.; Gandara, C. Using performance methods to enhance students’ reading fluency. J. Educ. Res. 2016, 109, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.; Schwanenflugel, P.J. A Longitudinal Study of the Development of Reading Prosody as a Dimension of Oral Reading Fluency in Early Elementary School Children. Read. Res. Q. 2008, 43, 336–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollingsworth, P.M. An experiment with the impress method of teaching reading. Read. Teach. 1970, 24, 112–114. [Google Scholar]

- Hollingsworth, P.M. An experimental approach to the impress method of teaching reading. Read. Teach. 1978, 31, 624–626. [Google Scholar]

- Nichols, W.D.; Rupley, W.H.; Rasinski, T. Fluency in Learning to Read for Meaning: Going Beyond Repeated Readings. Lit. Res. Instr. 2008, 48, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilfong, L.G. Building Fluency, Word-Recognition Ability, and Confidence in Struggling Readers: The Poetry Academy. Read. Teach. 2008, 62, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamm, L.; Denton, C.A.; Epstein, J.N.; Schatschneider, C.; Taylor, H.; Arnold, L.E.; Bukstein, O.; Anixt, J.; Koshy, A.; Newman, N.C.; et al. Comparing treatments for children with ADHD and word reading difficulties: A randomized clinical trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2017, 85, 434–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foorman, B.; Beyler, N.; Borradaile, K.; Coyne, M.; Denton, C.A.; Dimino, J.; Furgeson, J.; Hayes, L.; Henke, J.; Justice, L.; et al. Foundational Skills to Support Reading for Understanding in Kindergarten through 3rd Grade (NCEE 2016-4008); National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance (NCEE), Institute of Education Sciences: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblatt, L.M. The Reader, the Text, the Poem: The Transactional Theory of Literacy Work; Southern Illinois University Press: Carbondale, IL, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Ransom, J.C. New Criticism literacy theory. Va. Q. Rev. 1937, 14, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).