1. Introduction

Medicine integrates science to cure the affected body part, but it heavily relies on effective communication between doctors and patients (

de Haes and Bensing 2009, p. 287;

Panda 2006, p. 138). Given that over half of the world’s population is multilingual (

Grosjean 2021, p. 28), language barriers often arise in medical consultations, especially in regions with more than one official language.

Multilingual communication can pose significant challenges to healthcare, especially when doctors and patients do not share the same first language or possess different levels of language proficiency, leading to various communication approaches. To overcome these barriers and ensure good communication, several strategies can be adopted: simplification of language, using interpreters, and incorporating visual aids are a few examples. Additionally, if the parties involved are bilingual, they may switch between two or more languages during a conversation, a linguistic phenomenon called code-switching (

Gardner-Chloros 2009, p. 202).

This study analyzes the patterns associated with language choice and code-switching in bilingual medical consultations in Galicia, a Spanish region with two official languages, Galician and Spanish, two Romance languages with a high level of intelligibility and high level of bilingualism, at least passively (over 95% claims to understand both languages,

IGE 2018). More specifically, the paper examines the general linguistic behavior outside the doctor’s office to understand the specific linguistic behavior of bilingual family doctors and patients. Patients and healthcare professionals have the right to use either language in healthcare settings. However, Spanish traditionally holds higher social prestige and is the language usually associated with professional settings such as medicine or law. The research question was as follows:

- -

What general and specific linguistic behavior patterns in bilingual medical consultations can be identified in this Galician social context? Does the reported linguistic behavior differ from the actual behavior in medical consultations?

The hypothesis proposes that bilingual speakers (doctors and patients) negotiate their language use in each interaction due to their language competencies and preferences, as well as other extra-linguistic factors related to the social and communicative context. A medical consultation, which combines interpersonal and transactional goals, might be a setting with a higher tendency to employ code-switching as a communication strategy. However, speakers might consider that they alternate between Galician and Spanish less often than they do in reality.

By exploring these sociolinguistic dynamics, this research contributes to the understanding of language negotiation and code-switching in bilingual medical consultations, highlighting its complexity and the potential need for reevaluating language-proficiency requirements for healthcare professionals in Galicia. Furthermore, this study aims to deepen the understanding of healthcare interactions as a semi-formal and professional environment, a less explored area than colloquial contexts (

Mondada 2007, p. 298). This study also proposes to open the debate on language-proficiency requirements in the Galician healthcare system.

This paper first presents the theoretical background of code-switching, the Galician sociolinguistic context, and bilingual healthcare.

Section 3 explains the methodology and dataset used in this study.

Section 4 presents the main findings from the analysis, which are discussed in

Section 5. The paper concludes with some final remarks and briefly outlines potential future research and implications in linguistic politics emerging from this study.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Code-Switching

Code-switching is a common phenomenon among bilinguals, involving the alternating use of two or more languages within a conversation (

Matras 2009, p. 101;

Gardner-Chloros 2009, p. 202). This is not just a random occurrence but a deliberate communication strategy, i.e., a functional and driven language process that acquires social, discourse, or referential meaning in the conversation (

Matras 2009, p. 105;

Heller 1988, pp. 3–4).

Gumperz (

1982) defined code-switching as a conversational or discursive strategy, describing it as a way to indicate connections between themes, differentiate old information from new, and convey the speaker’s perspective on the discourse (

Heller 1988, p. 4). This study adheres to a socio-discursive approach to code-switching, using the turn as the basic unit since spoken language does not always operate in terms of complete sentences (

Moreno Fernández [1998] 2015, p. 261). Thus, language alternation can take place between turns (the equivalent to inter-sentential switches) or within turns (intra-sentential switches) (

Poplack 1980;

Muysken 2013). Single-word switches are described as “exceedingly rare” but still accepted (

Poplack 2013, p. 13;

Bullock and Toribio 2009, p. 2).

The focus of the socio-discursive is on the speakers and their social context, including “social constructs such as power and prestige” (

Bullock and Toribio 2009, p. 14). The socio-discursive approach analyses this language contact phenomenon as a social-embedded discursive practice in interactions between speakers responding to exiting rules in a specific speech community (

Heller 1988, p. 82;

Poplack 2013;

Myers-Scotton 1993;

Gardner-Chloros 2009). In bilingual communities, language alternation is a routine part of life; speakers frequently switch between languages. Thus, it can offer a better understanding of how the individual is articulated within a social context and is “highly variable between communities and between individuals” (

Gardner-Chloros 2009, p. 18). The primary function of code-switching is communicative, facilitating communication among bilinguals (

Gardner-Chloros 2009, p. 202). It is distinct from code-mixing, a non-functional alternation of languages (

Auer 2009, p. 491).

Finally, language choice, language accommodation, and code-switching are closely related phenomena. Bilingual speakers can select the most appropriate language (as well as varieties, registers, etc.) to speak in each context, accommodating the other’s language or alternating languages, thus fulfilling socio-discursive functions. Some studies even present code-switching as a form of speech accommodation (

Prys et al. 2012, p. 420). This theory, originally a sociopsychological model developed in the 1970s (

Giles and Ogay 2007), can be combined with code-switching, as it is in this study, understanding both phenomena as complementary strategies to regulate the communicative distance between speakers.

2.2. Galician Context

Galicia has two official Romance languages that are closely related and highly intelligible. Thus, the Galician speakers have a high level of bilingual competence among speakers, at least in a passive capacity. According to the latest official survey (

IGE 2018), nearly the entire population claims to be able to understand Galician (95.46%), while 88.05% report being able to speak the local language. Furthermore, approximately half of the population speaks only Galician or Spanish daily, while 44.69% are active bilinguals, meaning that they speak both languages with a predominance of either Galician (21.55%) or Spanish (24.21%). However, reading and writing competencies are less balanced. Specifically, 14.95% of the population report difficulties in reading, and 37.86% report low written skills in Galician. Most of these individuals are older adults who received their education during the dictatorship (1939–1975), when Spanish was the only language in school. This situation changed with the advent of the democratic era. Galician is more commonly spoken among older individuals residing in rural areas and with lower levels of education, which has traditionally attributed the local language to a lower prestigious status compared to Spanish, the preferred language for younger and higher-educated speakers in urban areas.

Due to centuries of intense contact, both languages have been heavily influenced by each other. Galician presents an intriguing case for study; it is described as a “dynamic and lively scenario of language shift” (

Kabatek 2017, p. 42). It is, therefore, an ideal sociolinguistic scenario in which to observe the dynamics of language change beyond linguistic necessity. This aspect is especially relevant in a communicative context, such as a medical consultation, where efficient and clear communication is essential to solve the health problem. This study focuses on semi-urban areas, which represent a shift towards bilingualism and an increasing preference for Spanish (

Monteagudo et al. 2021, p. 9), making them ideal for examining the dynamics of code-switching.

As a result of the linguistic and social proximity between Galician and Spanish, both languages have undergone processes of linguistic displacement in both directions (

Soto Andión 2014, p. 220). Hence, code, in this context, refers to a language and its varieties that “a person chooses to use on any occasion, a system used for communication between two or more parties” (

Wardhaugh [1996] 1992, p. 102). It is viewed as a strategic communication tool within interactional negotiations. Although research in this area is less extensive than in other bilingual contexts, several studies have contributed valuable insights (

Álvarez Cáccamo 1990,

2013;

Prego Vázquez 1997,

2010;

Vázquez Veiga 2003;

Acuña Ferreira 2013,

2017;

Diz Ferreira 2017;

Pawlikowska [2015] 2020).

The study of code-switching in Galicia is often intertwined with other language contact phenomena, such as borrowings and interferences, contributing to discussions about preserving Galician in its standard variety. Code-switching has become more prevalent in modern society as bilingualism stabilizes, contrasting with earlier associations of Galician and Spanish with different socioeconomic groups in rural and urban areas (

Silva Valdivia 2013, p. 305).

2.3. Bilingualism in Healthcare

2.3.1. Bilingual Medical Consultations

Healthcare has been conducted primarily through spoken encounters in the form of medical consultations (

Brown et al. 2006, p. 81), which are unique communicative settings characterized by specific purposes, fixed spatial settings, structured communicative formats, limited timeframes, and participants with asymmetrical interactional roles (

Pilnick and Dingwall 2011;

Hernández López 2009). In a doctor’s office, two institutions are combined in a medical consultation: a government (public healthcare) and a workplace (clinic), sharing features with other institutions, such as administrations or schools (

House and Rehbein 2004, p. 5;

Ehlich and Rehbein 1994). Consultations between a doctor and a patient are defined as “meetings between experts in which different kinds of expertise are shared through dialogue and discussion to facilitate decision-making” (

van Eemeren et al. 2021, p. 11). This different expertise alludes to how physicians and patients work together to gather relevant information and identify and provide a medical solution to a health problem. Thus, good communication skills are fundamental to delivering good service; otherwise, “neither a diagnosis nor a treatment plan can be established” (

de Haes and Bensing 2009, p. 287).

Medical consultations in the public healthcare system within bilingual or multilingual regions are required to provide a service in all official languages, such as Canada (

Drolet et al. 2014), Switzerland (

Lüdi et al. 2016), or regions of Spain (e.g., Galicia) and the UK (e.g.,

Wales, Roberts and Paden 2000;

Roberts et al. 2007). In the non-official bilingual or multilingual contexts often seen in migrant communities, consultations may involve switching to assist patients with limited national language proficiency.

Effective bilingual healthcare communication encompasses two main strategies: utilizing one’s communicative repertoire and leveraging the linguistic skills of others. Speakers can simplify the language, reformulate the message, use body language, or employ extra-linguistic techniques like drawings. Further, other possibilities exist, such as mediated communication through professional or ad hoc interpreters or multilingual written materials. Hence, the linguistic competencies of the patient and healthcare professional, as well as the availability of resources, influence the choice of strategy.

Healthcare professionals utilize various strategies, such as adjusting tone, employing colloquial terms, or reducing physical distance to improve patient rapport and understanding (

Milmoe et al. 1967;

Vickers and Goble 2018). In contemporary healthcare interactions, code-switching has been described as a strategy to help communication effectiveness, which is crucial for patient well-being (

Anderson 2012). In bilingual settings, alternating languages can fulfill discursive and interpersonal objectives, fostering a sense of kinship and trust between doctor and patient (

Hall et al. 1981;

Wood 2018). Language alternation has been studied in non-mediated consultations, fulfilling socio-discursive functions, such as greetings, building interpersonal relationships, relaxing tension, assuring patients, and explaining sensitive or complex information (

Odebunmi 2010,

2013;

Singo 2014). These bilingual communicative strategies highlight the potential of code-switching to improve medical communication and address challenges in patient–physician interactions.

2.3.2. Galician Healthcare System

Bilingual healthcare in Galicia operates under a legal framework that recognizes Galician and Spanish as official languages (Article 3,

Constitución Española 1978). The Galician Linguistic Normalization Law (

Parlamento de Galicia 1983) and the General Plan for the Normalization of Galician (

Xunta de Galicia 2004) are the two primary legal references for promoting the use of Galician, particularly in public domains like healthcare. These regulations aim to increase awareness, prevent linguistic discrimination, and encourage the use of Galician in healthcare settings.

In practice, however, the presence of Galician in the medical field is limited. At the University of Santiago de Compostela, only 2.36% of teaching hours in the Degree of Medicine are conducted in Galician (

USC 2021). This predominance of Spanish is attributed to the influence of non-local students and a tradition of teaching mainly in Spanish. The General Plan for the Normalization of Galician (

Xunta de Galicia 2004) argues that using Galician can improve doctor–patient relationships and healthcare efficiency, challenging the notion that Spanish is more suited for professional contexts.

Despite legal protections and policy initiatives, Galician faces several challenges in healthcare. The PNL’s analysis reveals a disparity between the theoretical benefits of Galician and its actual application in healthcare settings. For instance, while Galician is widely spoken in the region, its use in medical interactions is less common, especially in writing. This discrepancy is attributed to a lack of written proficiency and the association of writing with standard language varieties. However, the Style Manual of the Galician Public Healthcare Service (

SERGAS 2015) published by the SERGAS (Galician Healthcare Service) promotes communication in the patient’s native language, not specifying further instructions. In other words, the employer recommends that the clinic personnel accommodate the patients’ language, whether they speak Galician or Spanish.

According to the Report of the Observatory of the Galician Language (

OLG 2008, hereafter Report OLG), Galician is the preferred language for oral interactions with patients in primary care. However, Spanish is still the preferred language for interactions between professionals, internal meetings, and written documents (Report

OLG 2008, pp. 62–66). Language attitudes among healthcare professionals are generally positive towards Galician, especially when interacting with elderly patients (63.6% of interviewed doctors consider Galician an advantage for workers in primary care) (Report

OLG 2008, p. 75). Only 12.7% report insufficient use of Galician in primary care (Report

OLG 2008, p. 78). Legal provisions ensure patients’ rights to communicate in their preferred language, Galician or Spanish. Nevertheless, in practice, this is not always the case. While the public healthcare system includes language requirements for Galician, it is considered an additional merit (5 out of 60 points); however, it is not a reason to discard candidates.

3. Materials and Methods

The current study investigates the linguistic phenomenon of code-switching within the sociolinguistic Galician framework, particularly focusing on bilingual medical consultations in primary care. Thus, I conduct a sociolinguistic and discursive analysis using a mixed-methods approach with a two-fold dataset, as detailed in the following chapter.

3.1. Data Collection

The data collection combines a two-fold dataset. The first is a corpus with 586 audio-recorded consultations and eight semi-structured interviews with all the family doctors and resident doctors who participated in the recordings (

de Oliveira and Hernández Flores 2014). The second comprises 208 questionnaires and 15 sociolinguistic interviews with informants (own collection in 2021). The total material processed in this study amounts to circa 102 recorded hours.

3.1.1. Corpus Data: Audio-Recorded Consultations

The corpus was collected from a primary care clinic in a semi-urban Galician town with circa 10,000 inhabitants, serving urban and rural populations (

de Oliveira and Hernández Flores 2014) (see

Institutional Review Board Statement). The consultations were recorded during a week in 2014 without the presence of the researchers in the doctor’s office during the recordings.

The entire corpus encompasses approximately 800 consultations (the corpus remains not fully explored), including primary care, emergency room, and pediatric consultations. This research focuses on primary care consultations, a total of 586 consultations from six family doctors (see

Table 1). All family doctors in the corpus are between 50 and 60 years old. On average, each consultation is 8 min and 31 s. Out of 586 consultations, 178 interactions have instances of language alternation.

3.1.2. Questionnaires

The questionnaires were conducted in 2021 in a semi-urban town with demographic and sociolinguistic characteristics similar to the town where the corpus with consultations was recorded (see

Appendix A). Adhering to the PRESEEA methodology (

Moreno Fernández [1996] 2021), these questionnaires were stratified across key social variables such as sex, age, and education level. The informants provided a rich dataset on language use, knowledge, and attitudes towards bilingualism and code-switching, thus offering a multifaceted view of the sociolinguistic dynamics.

The sample was carefully constructed to ensure representation, with a minimum of three participants per quota. In total, 208 responses were received, with a higher proportion of participation from women with higher education (see

Table 2). Some demographic profiles were more challenging to locate than others due to the specific characteristics of the community represented (e.g., young individuals with only primary education), leading to a lower number of responses in these groups. However, the actual distribution, concerning both population and education levels, corresponds to the sample:

Sex: 29.3% are men, and 70.7% are women;

Population: 66.3% live in rural areas and 33.7% in the urban area;

Education level: 16.82% have primary education, 33.18% completed secondary school, and 50% of the informants have high education.

Table 2.

The final sample collected for this study (208 questionnaires).

Table 2.

The final sample collected for this study (208 questionnaires).

| Age | 18–34 | 35–49 | 50–64 | +65 |

| Education | W | M | W | M | W | M | W | M |

| Primary | 4 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| Secondary | 18 | 5 | 18 | 10 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 3 |

| Superior | 28 | 12 | 41 | 6 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| Total | 71 | 84 | 32 | 21 |

The wide age range of these informants, from 18 to 89 years old (mean = 43.28 years old), allowed for a comprehensive exploration of linguistic practices across generations of people from different backgrounds.

3.1.3. Semi-Structured Interviews

Semi-structured interviews further enriched the methodology to contextualize the results obtained from the survey and the language behavior observed in the audio-recorded consultations. First, the dataset comprises interviews with eight doctors, including six family doctors and two residents, as part of the “Corpus de interacción médico-paciente” (

de Oliveira and Hernández Flores 2014). These interviews were conducted in Spanish because the interviewer could not speak Galician, and the total was nearly six hours. The family physicians (three men and three women), ranging from 25 to 33 years of medical experience, and the two female resident doctors (first-year and third-year) displayed varied language preferences and backgrounds. In the second dataset, the semi-structured interviews were collected by this author in the same town as the questionnaires (see

Appendix B). The selection of fifteen informants, who did not participate in the questionnaires and had no previous relation with the researcher and interviewer, was conducted based on sex, age, education level, population (urban or rural), and linguistic behavior (Spanish speaker, Galician speaker, or active bilingual in their everyday life). Interviews in the second dataset were conducted by the researcher, mainly in Galician; only two out of fifteen were conducted in Spanish, accommodating the participant’s language preferences. With their varied sociolinguistic backgrounds, the interviewees brought a broad spectrum of perspectives on bilingualism and language use in healthcare to the forefront. This second dataset contains circa fourteen hours of recordings.

3.2. Methodology

This paper follows a mixed-methods approach, integrating sociolinguistics and sociopragmatics through quantitative and qualitative methods. This research is part of a more significant project, a doctoral dissertation (

Rodríguez Tembrás 2022), which presents the findings on code-switching in bilingual medical consultations divided into three dimensions, as follows: (a) social dynamics (overview and contextualization of the phenomenon); (b) interpersonal dynamics (CS as a distance regulator); and (c) situational dynamics (CS as a communicative strategy within the consultation). This division responds to understanding a doctor–patient interaction as an intersection of a medical and a social arena, which allows addressing “a variety of dilemmas inhabiting the medical visit” (

Heritage and Maynard 2006, p. 19).

Data from questionnaires, semi-structured interviews, and audio-recorded consultations were combined to analyze the three dimensions. Ensuring the ethical integrity of the study, the data collection process adhered to all anonymity protocols and comprehensive legal guidelines. First, the corpus with audio-recorded consultations and interviews with doctors (

de Oliveira and Hernández Flores 2014) involved securing written informed consent from multiple entities: the Galician healthcare authorities (regional Ethics Committee), clinic managers, healthcare workers, and the patients. Before recording, the doctors informed the patients about the study and their rights and asked them to sign a written consent. The researchers were not inside the doctor’s office during the recordings. The informants in the second dataset, semi-structured interviews, and questionnaires accepted participation in the study when sending the response and signing an informed written consent form for the recording.

This study juxtaposes reported language behavior from questionnaires and sociolinguistic interviews with observed natural language behavior in the audio-recorded consultations, offering a comprehensive view of linguistic dynamics. This paper focuses on the social dynamics, i.e., the analysis of how the social context influences interactions between family doctors and patients who switch between Spanish and Galician during medical consultations.

3.2.1. Social Dynamics

The social dynamics explain the language use and attitudes towards Spanish and Galician in a small semi-urban town, focusing on the specific language behavior inside and outside the doctor’s office. This paper focuses on social dynamics regarding language use and attitudes inside and outside the doctor’s office, analyzing code-switching patterns with additional contextual information about language choice and accommodation. First, I listened to all the data and organized the results using an Excel document. Interviews and audio-recorded consultations were manually anonymized (data protection), annotated (using deductive and inductive coding strategies), and transcribed using the Val.Es.Co transcription system.

The responses to the questionnaires and metadata from the audio-recorded consultations were exported and investigated using Python in Jupyter Notebook to carry out a descriptive and correlational statistical analysis (Chi-Square and Cramer’s V) and visualize the data. All absolute and relative frequencies related to monolingual and bilingual medical consultations were extracted regarding the corpus metadata. Likewise, the frequencies were crossed with the available sociolinguistic data about doctors and patients and other metadata about the consultation, applying the corresponding correlational tests. Excerpts of the interviews and medical consultations were used to combine the statistical data from the questionnaires and audio-recording consultations, focusing on language selection and code-switching inside and outside the doctor’s office.

3.2.2. Hybrid Bilingual Practices

This paper adheres to a socio-discursive approach to study language choice, accommodation, and code-switching. This acknowledges the linguistic continuum between Spanish and Galician, where interferences, borrowings, and code-switching intermingle in speech. Distinguishing where one language ends and the other begins is challenging due to their close relationship. Within this context, contact phenomena can simultaneously affect a speech segment, complicating the identification of specific languages (

Rodríguez Yáñez and Casares Berg 2003, p. 363). This continuum is seen in hybrid bilingual practices across various socio-economic and situational contexts, particularly in colloquial oral interactions (

Pawlikowska [2015] 2020, p. 176). Consequently, we do not classify the following as code-switching and they are, therefore, not included in the analysis if: (a) Galician diminutives in Spanish reflecting grammatical transfers (e.g.,

le duelen las maniñas your little hands hurt); (b) borrowings in both directions (e.g., G > S:

dolor, sangre; S > G:

colo, leira); and (c) the conversational routines in Spanish, as greetings and farewells in Spanish in Galician conversations. In the example below, collected from the audio-recorded consultations, Standard and Colloquial Galician, as well as Spanish, are mixed in the farewell in a consultation where the doctor (D) and patient (P) speak Galician:

| 1 D: veña/hasta loguiño |

| alright, see you (colloquial GAL) |

| 2 P: hasta luego/[bos días] |

| see you! (SPA), good morning (GAL) |

| 3 D: [hasta logo!] |

| see you (colloquial GAL) |

4. Results

In the following, this section will present the main results regarding (1) language accommodation and (2) language choice (monolingual and bilingual consultations), as a complement to the focus of this analysis, the (3) patterns associated with code-switching in medical consultations. Data from the first dataset, comprising questionnaires and interviews with doctors (

de Oliveira and Hernández Flores 2014), and from the second dataset (questionnaires and semi-structured interviews) will be combined in the analysis.

4.1. Language Accommodation

The data on language accommodation reveals a significant correlation: 37.98% of participants in the survey claim to be active bilinguals. This closely matches the 38.46% who admit to adapting their language when speaking with another bilingual speaker (see

Figure 1). When asked, “If I talk with someone who can speak Galician and Spanish…” around 40% of the respondents would choose to mirror their interlocutor’s language, regardless of their own preference. In contrast, six out of ten prefer to keep their regular language, confident that the other person will comprehend. This reflects an underlying language negotiation process, where individuals either shift their language to match their conversation partner or mutually agree to speak in their languages without causing any issues.

Active bilinguals choose which language to speak according to the situational context or their role. For instance, the professional speakers use Galician to perform their duties as, typically, public servants working in public administration:

We here (

Town Hall), what we do is if someone speaks to us in Galician, we reply in Galician, and if they speak in Spanish… Well, those who speak in Galician, speak in Galician. I tend to speak Spanish. For instance, if someone talks to me in Spanish, but well, in my work, I use Galician a lot. I always try to start with Galician, you know? I initiate the conversation. That is where I became more fluent at work because before, to be honest, Galician was very difficult for me, and now I feel quite comfortable speaking Galician.

1(Informant 1: woman, 38 years old, superior education)

Doctors in the public healthcare system and public servants also deal with patients with Galician or Spanish as their first language. Dr. E from the corpus with audio-recorded consultations, a bilingual female physician with Galician as her preferred language, is aware of her tendency to accommodate and code-switch (“I also mix”) between her two native languages.

Interviewer: You initially addressed them in Galician.

Dr E: Yes, because most of them speak Galician. So, I address them in Galician, and then, depending on how they speak to me, I answer them in Spanish or Galician. And sometimes, I also mix.

When considering a scenario where the physician adapts to the patient’s language at the start of the consultation, the informants’ perception (questionnaires) is generally neutral. If the doctor adjusts his or her language to match the patient’s:

The majority (69.56%, n = 144) reacts neutrally to this hypothetical language accommodation, as explained by an informant in the semi-structured interviews:

Informant: For example, I had another doctor, and everything was in Galician, everything (…) but everything was in Galician, everything.

Interviewer: And did you feel more comfortable with him because he was speaking …?

Informant: Well, it does not matter to me. (Informant 14: woman, 77 years old, primary education);

22.22% (n = 46) recognize they would feel more comfortable inside the doctor’s office if the doctor accommodated their preferred language, as defended by an informant in the interviews:

Everyone was speaking Galician in the line, in the queue. We were talking with others in Galician. There was no Spanish anywhere. Maybe some were, but ninety percent and surely more of us were speaking in Galician. And we arrived there, and the nurse who let us in to arrange us was speaking in Spanish. I said ‘Madam!’, I protested, ‘Madam!’ I told her what I just told you: ‘Most of us here speak Galician and you come with your Spanish’. And a nurse who was behind said, ‘there you go’, already agreeing with me. She changed. She changed, she started (…). (Informant 5: man, 77 years old, superior education);

4.2. Language Choice: Monolingual and Bilingual Interactions

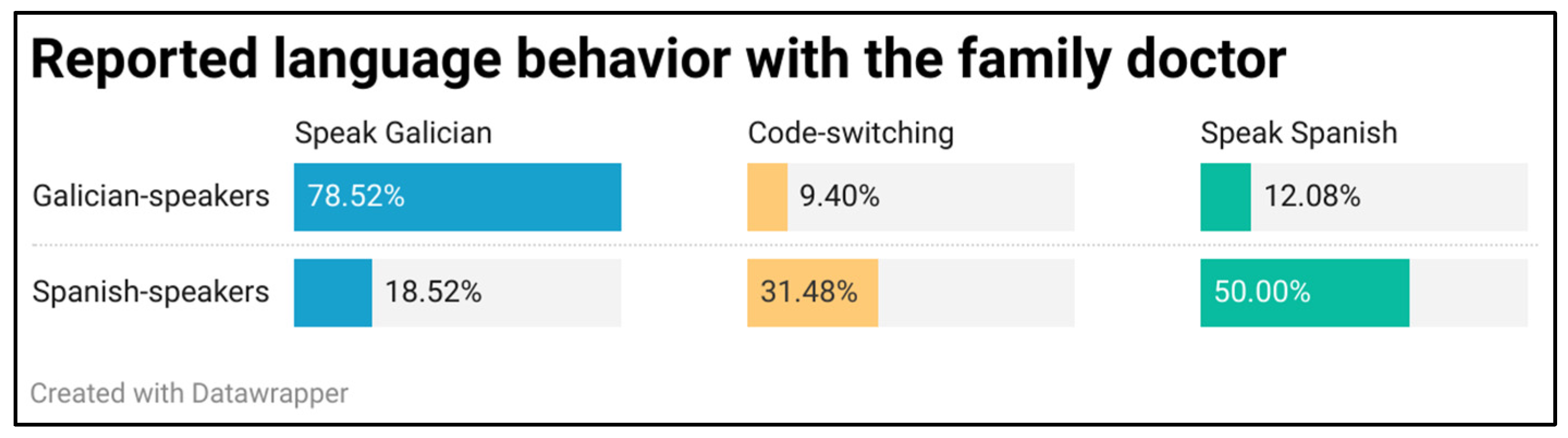

Galician speakers demonstrate greater consistency in their language choices at the doctor’s office compared to Spanish speakers (see

Figure 2). A significant majority, eight in ten (78.52%, n = 117), consistently use their everyday language, Galician, with their physician. Only a small fraction, one in ten (9.40%, n = 14), report switching between Galician and Spanish, similar to the proportion who opt to speak Spanish from the outset (12.08%, n = 18).

In contrast, Spanish speakers claim to be more flexible in their language use in medical settings. Only half (50%, n = 27) consistently speak Spanish with their doctor. Three in ten (31.48%, n = 17) alternate between Spanish and Galician, while two in ten (18.52%, n = 10) choose to speak Galician from the beginning of the interaction.

In the corpus (

de Oliveira and Hernández Flores 2014) consisting of 586 consultations, 57.67% (n = 338) of the interactions are monolingual. Of these monolingual consultations, 35.32% (n = 207) are in Galician, and 22.35% (n =131) are in Spanish. Thus, the doctor and the patient speak the same language in six out of ten consultations. The remaining 42.32% (n = 248) are bilingual, with 11.94% (n = 70) of interactions where each speaker maintains their preferred language, and 30.38% (n = 178) involve code-switching to varying extents.

When comparing the results obtained in the survey (reported linguistic behavior) and the corpus (actual linguistic behavior), some similarities and differences can be found. The survey and the corpus have a similar balanced distribution between consultations with and without language negotiation, i.e., bilingual and monolingual consultations:

Despite the apparent balance between monolingual and bilingual consultations in the corpus, when delving deeper into the audio-recorded encounters, we observed that Spanish-speaking physicians usually stay in the same language; they speak exclusively Spanish in 96.79% of the consultations. Consequently, this inflexibility from the doctor’s side contextualizes the higher incidence of bilingual consultations without code-switching in the combination Doctor-Spanish/Patient-Galician (11.77%) (see

Table 3). The survey and the corpus indicate that consultations involving Spanish-speaking patients and Galician-speaking doctors are relatively rare, at 1.46% and 0.17%, respectively. This suggests that Galician-speaking doctors are more likely to adjust their language to the patient’s language, as opposed to their Spanish-speaking counterparts. Informant 13 observed this inflexibility:

They can spend there fifty years. Maybe they will say some basic little phrase or an alphabet from time to time, but no, they do not change.

(Informant 13: man, 62 years old, secondary education)

For some speakers, maintaining Galician while interacting with a Spanish-speaking doctor goes beyond mere preference; it becomes almost an ideological choice. They believe in their right to speak their preferred language, particularly in public services such as primary healthcare, as explained by Informant 5:

No, I refuse. In the case that the doctor speaks to me in Spanish, I speak to him in Galician. And he continues speaking in Spanish and I continue speaking in Galician. There are some who change, but the majority do not try. They keep speaking Spanish and I (speak) in Galician.

(Informant 5: man, 77 years old, superior education)

Example 1. Doctor speaks Spanish and patient speaks Galician.

The patient (P) (woman, age range: old adult) suffers from heartburn and discomfort. P is a Galician speaker, and the doctor (D) is a non-Galician Spanish speaker. After a brief exploration of the stomach, the woman refers to a lump in her breast. The doctor is not concerned about the lump and prescribes an antacid. The consultation usually proceeds with both speakers maintaining their preferred language.

| 1 D: muy bien/ entonces/ ahora me dice// ¿qué le pasa? |

| very well, so now tell me, what seems to be the problem? |

| 2 P: mire/ doime o estómago moito/ pola mañán xa me levanto con asidez no estómago |

| look, my stomach hurts a lot, in the morning I already wake up with acid in my stomach |

| 3 e despois pola tarde= |

| and then in the afternoon |

| 4 D: ¿y la acidez? |

| and the acidity? |

| 5 P: =árdeme moitísimo |

| it burns me a lot |

| 6 D: ¿por dónde nota la acidez? |

| where do you feel the acidity? |

| 7 P: si/ por aquí/ que me chega hasta a boca// e dolor así aquí na espalda e máis dolor de cabeza |

| yes, right here, it reaches up to my mouth, and there is this pain here in my back and more headaches |

| 8 D: ¿y desde cuando tiene esta acidez? |

| and how long have you had this acidity? |

| 9 P: a asidez/ xa hai moito tempo que a teño/ pero como estaba tomando o protector/ |

| the acidity, I have had it for a long time, but because I was taking the protector |

| 10 non notaba [moito/ pero ahora ó deixar→] |

| I did not notice it much, but now after stopping→ |

4.3. Code-Switching

Nearly half of the participants in the survey (49.04%, n = 102) reported switching languages in specific public settings, a proportion exceeding the number of functional bilinguals (37.98%). This question aimed to understand language dynamics in medical environments and whether language choices are influenced by the context, presenting a wide range of public domains. Participants could select more than one option. The context in which they claim to switch more is the public administration (48.04%), followed by the healthcare domain in second place. 27.45% of respondents reported adopting the doctor’s language instead of their preferred one upon entering the doctor’s office.

Nearly 30% of participants in the questionnaire (28.85%, n = 58) self-reported switching languages at some point during doctor–patient interactions. The primary self-reported reasons for code-switching, in order of frequency, include: (a) explaining essential details, (b) asking about treatment, (c) emphasizing an opinion, (d) discussing sensitive personal matters, and (e) joking. These motivations reflect both social and discursive elements. Participants could cite multiple reasons (up to five) or suggest their own, as detailed in

Figure 3, summarizing the survey responses.

The top three reasons (explanations, inquiries, emphasis) align with the transactional objective of the consultation, where both patients and doctors aim to resolve medical issues clearly and efficiently. This approach involves utilizing various communication strategies to prevent misunderstandings and achieve a resolution quickly. The primary goal is to meet the consultation’s transactional needs while ensuring the patient’s voice is heard, thereby balancing the asymmetry between patient and doctor.

The remaining two reasons pertain to the interpersonal aspect of the doctor–patient relationship. The results show that 18.96% (n = 11) switch languages when discussing profoundly personal or sensitive topics, possibly choosing the language they associate most with emotions, and that 12.07% (n = 7) use code-switching for humor. Discussing sensitive issues or employing humor seems to help participants bridge the gap with their interlocutors in their roles as patients and physicians.

A similar incidence of code-switching was observed in natural interactions. There is language alternation in three out of ten consultations, constituting 30.38% (178 out of 586) of all consultations. The extent of code-switching can vary, with some interactions featuring more frequent switching than others. Correspondingly, 28.85% of survey respondents admit they switch languages during visits to the doctor’s office. The pattern of code-switching is typically one-sided, with either the patient or doctor switching languages (25.26%, n = 148) rather than both parties (5.12%, n = 30). Furthermore, it is more common for patients (15.53%, n = 91) to code-switch than for doctors (9.73%, n = 57).

Table 4 displays a total count of all consultations in the corpus where speakers employ code-switching in the different possible combinations.

Example 2. Doctor speaks Spanish and patient code-switches.

A patient (P) (woman, age range: old adult) visits the family doctor (man, approximately 55 years old, Spanish speaker) on behalf of her husband. The reason for the appointment is to obtain the blood test results. Further, she is also concerned about the swelling of her husband’s legs and asks about the possible cause. The woman alternates constantly between Galician and Spanish, while the doctor always speaks in his preferred language, Spanish. This combination (P-CS/D-Spa) is the primary one in the corpus regarding code-switching. The patient switches to Spanish (in bold), the doctor’s language, for emphasis (line 3), mitigation (line 10), and for providing simple answers that do not require much elaboration (line 12).

| 1 P: bueno/mire/ eh→/escoite unha cousa/que vou desir eu//e o das pernas// |

| well, look, listen to one thing, what I am going to say, about the legs |

| 2 e logho de que será?/ou é (( )) que hinchan e hínchanlle as pernas// |

| and what could it be? Or is it (()) that they swell and his legs swell |

| 3 y ese es el problema que tiene |

| and that is the problem he has |

| 4 D: pero/¿le hinchan mucho/ mucho/ mucho? |

| but, do they swell a lot, a lot, a lot? |

| 5 P: bueno |

| well |

| 6 D: ¿sólo a la tarde-noche? |

| only in the afternoon-night? |

| 7 P: home/claro |

| well, of course |

| 8 D: se levanta con ellas |

| he wakes up with them |

| 9 P: no//levántase con elas baixas/pero despois/os tobillos e así un pouco pa’riba// |

| no, he gets up with them not swollen, but then, the ankles and so a little bit up |

| 10 pero/el xa toma eso pa…mear/pero→ |

| but he already takes that to…urinate, but |

| 11 D: ¿a qué hora está tomando la Furusemida? |

| at what time is he taking the Furosemide? |

| 12 P: a la mañana |

| in the morning |

| 13 D: pues que la pase al mediodía |

| then he should move it to midday |

5. Discussion

In light of the results described in this study, doctors and patients seem to strategically select and switch between Spanish and Galician to achieve interpersonal and communication goals. Approximately half of the consultations are bilingual, either with or without code-switching (with varying degrees), underscoring the significance of language negotiation. Galician-speaking patients show greater linguistic flexibility while Spanish-speaking doctors infrequently switch to Galician. This behavior contradicts the reported behavior provided in the questionnaire, where more Spanish speakers than Galician speakers affirmed that they substantially employed code-switching (31.48% versus 9.40%). This behavior suggests persistent power imbalances between doctors and patients, at least in contexts with older doctors (between 50–60 years old) in semi-urban towns, with Spanish maintaining its prestige as the dominant language within the medical profession. This trend conflicts with the PNL’s recommendation for physicians to initiate consultations in Galician and switch to Spanish when necessary (

Xunta de Galicia 2004, p. 167). It also contrasts with the

OLG (

2008, pp. 60–87), which advocates for Galician as the default language for physicians at the beginning of consultations.

The findings also indicate that, although most speakers can at least understand both languages flawlessly, about half of the medical consultations involve bilingual communication through code-switching or mixed conversations. Moreover, a similar incidence between reported and natural language behavior shows consistency in the data. Notably, patient-initiated code-switching is more common when doctors speak Spanish, and is twice as prevalent as doctor-initiated code-switching. This reflects the persistent impact of social hierarchies on language choices in medical settings. Spanish-speaking doctors in the audio-recording consultations keep their preferred languages in 96.79% of the interactions. These robust data indicate a possible association with the most common patterns in bilingual consultations without code-switching, i.e., interactions where the doctor speaks Spanish, and the patient speaks Galician. The same occurs with the most usual combination related to recorded consultations with code-switching (the patient employs code-switching, and the doctor speaks Spanish). The two main reported motivations behind code-switching (questionnaires) are discursive (conducting consultations and explanations). However, a greater tendency to alternate languages is observed if the doctor speaks Spanish, perhaps in order to balance the communicative power dynamics in the interaction.

Four out of ten informants in the survey claim to accommodate the other’s languages. The attitudes towards language accommodation by the doctor are primarily neutral (“I would not care”, ≈70%) or positive (≈20%). Only a tenth part of the participants do not approve of this behavior. This refusal seems linked to the informants’ proficiency in both languages, at least passively, not seeing this accommodation as necessary. The questionnaire also shows that almost all respondents (97.57%) do not consider Spanish a communication barrier in medical consultations. Likewise, the same happens with positive attitudes. This suggests that patients received a positive effect due to language accommodation motivated by extra-linguistic factors.

The debate surrounding the requirement of Galician proficiency for public health physicians is complex. Nowadays, Galician proficiency is a merit, not a requirement. For instance, in Catalonia, another bilingual region of Spain, public doctors must demonstrate a C1 level in Catalan (CEFR). Although most Galicians understand both languages, the interaction with a doctor in any of the official languages often seems to transcend mere comprehension.

6. Conclusions

This paper has focused on the social dynamics of bilingualism in medical settings, specifically how doctors and patients communicate in primary care clinics in semi-urban environments. The study has examined the patterns of linguistic behavior both outside and inside the doctor’s office. Healthcare encounters appear to be a setting with a high incidence of bilingualism. Contrary to the proposed hypothesis, the reported linguistic behavior aligns with the observed behavior in the audio-recorded consultations. The data from the surveys concerning monolingual and bilingual consultations differ by approximately ten points.

To the best of our knowledge, this research constitutes the first exhaustive empirical study of code-switching in bilingual medical consultations (Galician–Spanish), combining data from questionnaires, semi-structured interviews, and audio-recording consultations. Further, it represents a novel study on language use in an institutional setting (healthcare), with significant resonance for society. This research unveils significant insights into code-switching in bilingual medical consultations in Galicia, in addition to language accommodation and language choice. It highlights code-switching as a strategy for language negotiation and meeting socio-discursive needs. The findings suggest reevaluating the requirement for healthcare professionals in Galicia to be proficient in Galician. Moreover, beyond linguistic implications, this study provides insights valuable for healthcare professionals, policymakers, and language planners in formulating strategies to enhance communication, increase patient satisfaction, and potentially improve healthcare outcomes in bilingual communities.

Future research will explore the motivations for code-switching related to the dual objectives of medical consultations: interpersonal, i.e., maintaining a trusting relationship, and transactional, i.e., maximizing communication effectiveness to find a professional solution to a medical issue.

Funding

Funding for data collection was provided by the University of Copenhagen (Project UC-CARE, 2013–2016) and Heidelberg University (Ph.D. thesis).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The corpus data collection (“Corpus de interacción medico-paciente”,

de Oliveira and Hernández Flores 2014) was conducted in accordance with the legal framework of the University of Copenhagen (514-0033/194000), and approved by the Comité Autonómico de Ética de Investigación de Galicia SERGAS (Approval Code 2014/013).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the University of Copenhagen and Heidelberg University.

Data Availability Statement

Questionnaire answers and transcriptions of the semi-structured interviews are available upon request from the corresponding author. Corpus data is not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions. The authors, Nieves Hernández Flores and Sandi de Oliveira, representing the University of Copenhagen, granted the researcher permission to use the data.

Acknowledgments

We thank the three anonymous reviewers and the editors for their insightful comments and suggestions, which significantly improved the quality of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Questionnaire

The original questionnaire was distributed in a bilingual version (Galician/Spanish). The translation into English is provided below in this appendix:

How old are you?

What studies have you completed?

Do you live in an urban or rural area?

What is your occupation (currently or before retirement/unemployment)?

- 5.

In which language did you learn to speak?

- 6.

In which language did you learn to read and write?

- 7.

In which language do you usually speak?

- 8.

In which language do/did your parents usually speak?

- 9.

In which language do you perform better in speaking, reading, and writing?

- 10.

Which language do you speak with your family: grandparents, parents, siblings, partner, children, grandchildren?

- 11.

Which language do you speak with the following people: friends, classmates/coworkers, boss, and clients?

- 12.

In which language do you engage in the following activities: reading, watching television, using the Internet or social media, and writing emails, letters, or other documents?

- 13.

On a scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree): (a) Galician is a cultural asset of Galicia, (b) Galician is useful in private life, and (c) Galician is useful in professional life.

- 14.

Where do you think Galician could be used more: in the media, in school, in healthcare, in church, in public administration, in businesses, and others?

- 15.

On a scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree): (a) Spanish is a cultural asset of Galicia, (b) Spanish is useful in private life, and (c) Spanish is useful in professional life.

- 16.

If I speak with someone who knows how to speak both Spanish and Galician: (a) I always answer in my habitual language; (b) I answer in the language they speak to me, whether mine or not; (c) others.

- 17.

If you sometimes switch languages in Galicia, on what occasions do you do so (besides speaking with someone who does not understand Galician): for shopping at local stores, shopping in city stores, talking to the doctor; for administrative procedures, in meetings at your children’s school or in the neighborhood community; for speaking with lawyers or banking personnel.

- 18.

In which language do they speak at the family doctor’s appointment?

- 19.

How often do you go to the family doctor?

- 20.

How long have you had your current family doctor?

- 21.

Do you see your family doctor in other places (as a neighbor)?

- 22.

Do you feel you can speak confidently with your doctor during the appointment?

- 23.

If the doctor speaks in Spanish, are there communication problems?

- 24.

Would you feel more comfortable if the doctor switched to the language you spoke at the beginning of the appointment?

- 25.

If the doctor does not speak your habitual language, do you switch languages at any point during the appointment?

- 26.

If you answered yes to the previous question, when do you switch languages? Options: to explain something important, ask about the guidelines for my treatment, talk about something personal, make jokes, or emphasize my opinion.

- 27.

When you go to an appointment with a specialist doctor at the hospital, which language do you speak?

- 28.

What do you do if you usually speak in Galician and the hospital doctor starts speaking to you in Spanish?

Appendix B. Interview Template

The original interview was conducted in Galician or Spanish, depending on the participant’s preference. The questions were adapted to the sociolinguistic characteristics of each participant. The translation into English is provided below in this appendix:

Section 1: General Data

Interview Date:

Interview Location:

Name (for anonymization):

Gender:

Place and year of birth:

Year of arrival in the town (if born elsewhere):

Life experience outside the town:

Residence (rural/urban):

Education and place:

Occupation and workplace:

Spoken languages:

General observations about the informant:

How is (town) to live in? Do you live in an urban or rural area? Where were you born? (If not in the area) How long have you been living here?

Have you ever lived elsewhere? (If yes) Where? How long? What did you do there? What motivated you to return? Is it very different from living here in Galicia?

In which language did you learn to speak at home? In which language do you usually speak? In which language do/did your parents usually speak? And your grandparents? (If they do not match) In which language did your parents speak to you? Why did they not speak in their everyday language?

Have you always spoken the same language you speak today? (If not) Why did you decide to switch the language?

What did you study? (In the case of older people without studies) How long did you go to school? How was the school at that time (during the dictatorship)? Was it very different from now? How? Was the language spoken in school different from the one spoken at home?

(In the case of informants with studies) Where did you study? How was that experience? In which language did you study? How did you speak with your classmates? Do you think the university environment influences language change?

Which languages do you feel more comfortable reading and writing? (if they are different regarding the spoken language)? Why? What about watching television, listening to the radio, using the internet and apps, posting on social media, watching advertisements, etc.?

Do you think the Galician spoken on RTVG is the same as what people speak?

When you speak with your family (list of different family members), in which language do you speak? (If different) Why? And with friends?

- 10.

How is (town) spoken? Is it different from other parts of Galicia? Do you think there is somewhere where Galician is spoken “better”? Are there cities or towns that are more Galician-speaking or Spanish-speaking?

- 11.

From your point of view, which language is more useful in private life: Galician or Spanish? Or are they equal? Why? And in the case of professional life? Why?

- 12.

Do you think Galician should be protected more, less, or equally? How do you assess the current situation (spoken less, more, or the same)? Furthermore, what do you think is the Galician’s future?

- 13.

What do you think of those who believe parents should transmit Spanish to their children or those who think Spanish (and other languages) should be prioritized in school? Moreover, do you know any cases of Galician-speaking parents who speak to their children in Spanish?

- 14.

Could Galician be used more in (town) or in general? Where? (Indicate some of the answers obtained in the survey)

- 15.

Was there ever a moment when you felt uncomfortable or discriminated against for using one language or another? Do you think some people are discriminated against for speaking a specific language?

- 16.

When you have to speak with someone who speaks (language), do you always answer in your habitual language, or do you adapt to the other person’s language?

- 17.

(If you change) Why? Do you sometimes change languages or mix both? Are you aware of this? In what situations do you change (communicative contexts)?

- 18.

What do you think of people who alternate between Galician and Spanish?

- 19.

How is the primary care clinic in your town?

- 20.

How would you rate your relationship with your family doctor? How long have you had the same doctor? Is he/she a neighbor in the town? Do you feel confident when you talk to him/her?

- 21.

Do you go accompanied to the doctor? Who goes with you? Does that person also participate in the consultation and help you?

- 22.

Have you ever had a doctor or nurse who was not Galician? Did they understand Galician? Do you think there was any communication problem? What happens when a healthcare professional is not a Galician?

- 23.

Which language does your doctor speak? Which language do you speak with him/her? Do they address you informally or formally? (If it does not match the informant’s L1) Would you prefer them to speak your language, or is it irrelevant?

- 24.

Do they mix Spanish and Galician in the consultation? Does the doctor switch the language with you? And do you with him/her? If they changed upon hearing you, would you feel more comfortable?

- 25.

Have you ever noticed that the language changed during the consultation? (If yes) Why did it change?

- 26.

Suppose you go to the clinic for a doctor’s appointment. When you enter the consultation room, how do you greet/say goodbye to the doctor?

- 27.

What do you think about doctors not being required to know how to speak Galician to have a position in SERGAS? Do you think they should be proficient, or is it less important than being a good doctor?

- 28.

Is it different from going to the primary care clinic? Why?

- 29.

In what language do doctors speak at the hospital? Is it like talking to the family doctor? (If not) Why do you think it is so? (If not matching the informant’s L1) Do you find it more difficult to understand or to make yourself understood?

- 30.

(Non-coincidence of L1) If the doctor speaks in X, would you change to that language or keep speaking in your preferred language?

- 31.

Do you think more, less, or the same Galician is spoken in the hospital? Why?

- 32.

Is there anything that should be improved regarding communication to offer better healthcare in Galicia?

Note

| 1 | The original quotations are either in Galician or Spanish. All translations into English are mine. |

References

- Acuña Ferreira, Virginia. 2013. Funciones socio-discursivas de las alternancias de gallego y español en la realización bilingüe de cotilleo. Spanish in Context 10: 199–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuña Ferreira, Virginia. 2017. Code-switching and emotions display in Spanish/Galician bilingual conversation. Text & Talk 37: 47–69. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Laurie. 2012. Code-switching and coordination in interpreter-mediated interaction. In Coordinating Participation in Dialogue Interpreting. Edited by Claudio Baraldi and Laura Gavioli. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: Benjamins Translation Library, pp. 115–48. [Google Scholar]

- Auer, Peter. 2009. Bilingual conversation. In The New Sociolinguistics Reader. Edited by Nikolas Coupland and Adam Jaworski. Houndmills: Palgrave, pp. 490–511. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez Cáccamo, Celso. 1990. The Institutionalization of Galician: Linguistic Practices, Power, and Ideology in Public Discourse. Ph.D. thesis (unpublished), University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez Cáccamo, Celso. 2013. “From ‘switching code’ to ‘codeswitching’: Towards a reconceptualisation of communicative codes”. In Code-Switching in Conversation: Language, Interaction and Identity. Edited by Peter Auer. London: Routledge, pp. 29–48. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Brian, Paul Crawford, and Ronald Carter. 2006. Evidence-Based Health Communication. Berkshire: McGraw-Hill Education. [Google Scholar]

- Bullock, Barbara, and Almeida Jacqueline Toribio. 2009. The Cambridge Handbook of Linguistic Code-Switching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Constitución Española. 1978. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 29 December 1978, 311. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/c/1978/12/27/(1)/con (accessed on 23 May 2024).

- de Haes, Hanneke, and Jozien Bensing. 2009. Endpoints in medical communication research, proposing a framework of functions and outcomes. Patient Education and Counseling 74: 287–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira, Sandi Michele, and Nieves Hernández Flores. 2014. Corpus de Interacción Médico-Paciente en Galicia. Unpublished. Copenhagen: University of Copenhagen. [Google Scholar]

- Diz Ferreira, Jorge. 2017. A construción da identidade rural na interacción bilingüe a través da negociación da escolla de código en secuencias de apertura. Estudos de Lingüística Galega 9: 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drolet, Marie, Josée Benoît Jacinthe Savard, Sébastien Savard Isabelle Arcand, Sylvie Lauzon Josée Lagacé, and Claire-Jehanne Dubouloz. 2014. Health Services for Linguistic Minorities in a Bilingual Setting: Challenges for Bilingual Professionals. Qualitative Health Research 24: 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehlich, Konrad, and Jochen Rehbein. 1994. Institutionsanalyse: Prolegomena zur Untersuchung von Kommunikation in Institutionen. In Texte und Diskurse. Edited by Gisela Brünner and Gisela Gräfen. Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag, pp. 287–327. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner-Chloros, Penelope. 2009. Code-Switching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Giles, Howard, and Tania Ogay. 2007. Communication accommodation theory. In Explaining Communication: Contemporary Theories and Exemplars. Edited by Bryan Whaley and Wendy Samter. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 293–310. [Google Scholar]

- Grosjean, François. 2021. Life as a Bilingual: Knowing and Using Two or More Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gumperz, John J. 1982. Discourse Strategies. No. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Judith A., Debra L. Roter, and Cynthia S. Rand. 1981. Communication of affect between patient and physician. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 22: 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, Monica. 1988. Codeswitching: Anthropological and Sociolinguistic Perspectives. Contribution to the Sociology of Language 48. New York and Amsterdam: Mounton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Heritage, John, and Douglas W. Maynard, eds. 2006. Communication in Medical Care: Interaction between Primary Care Physicians and Patients. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, vol. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández López, María de la O. 2009. La gestión de las Relaciones Interpersonales en la Interacción Médico-Paciente: Estudio Contrastivo Inglés Británico—Español Peninsular. Ph.D. thesis (unpublished), Universidad Pablo de Olavide, Sevilla, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- House, Juliane, and Jochen Rehbein, eds. 2004. Multilingual Communication. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Galego de Estatística (IGE). 2018. Enquisa Estrutural a Fogares. Coñecemento e Uso do Galego. Available online: https://www.ige.gal/web/mostrar_actividade_estatistica.jsp?codigo=0206004 (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Kabatek, Johannes. 2017. Dez teses sobre o cambio lingüístico (e unha nota sobre o galego). In Estudos Sobre o Cambio Lingüístico no Galego Actual. Edited by Xosé Luis Regueira and Elisa Fernández Rei. Santiago de Compostela: Consello da Cultura Galega, pp. 21–43. [Google Scholar]

- Lüdi, George, Nathalie Asensio, and Fabia Longhi. 2016. “Doctor, are you plurilingual?” Communication in multilingual health settings. In Managing Plurilingual and Intercultural Practices in the Workplace. Edited by George Lüdi, Katharine Höchle and Patchareerat Yanaprasart. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 139–52. [Google Scholar]

- Matras, Yaron. 2009. Language Contact. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Milmoe, Susan, Robert Rosenthal, Howard T. Blane, Morris E. Chafetz, and Irving Wolf. 1967. The doctor’s voice: Postdictor of successful referral of alcoholic patients. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 72: 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mondada, Lorenza. 2007. Bilingualism and the analysis of talk at work: Code-switching as a resource for the organization of action and interaction. In Bilingualism: A Social Approach. Edited by Monica Heller. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 297–318. [Google Scholar]

- Monteagudo, Henrique, Xaquín Loredo, Lidia Gómez, and Gabino S. Vázquez-Grandío. 2021. Mapa Sociolingüístico Escolar de Ames. Santiago de Compostela: Real Academia Galega. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno Fernández, Francisco. 2015. Principios de Sociolingüística y Sociología del Lenguaje. Barcelona: Editorial Ariel. First published 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno Fernández, Francisco. 2021. Metodología del ‘Proyecto para el estudio sociolingüístico del español de España y de América (PRESEEA)’. Lingüística 8: 257–87. First published 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Muysken, Peter. 2013. Language contact outcomes as the result of bilingual optimization strategies. Bilingualism, Language and Cognition 16: 709–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers-Scotton, Carol. 1993. Social Motivations for Codeswitching: Evidence from Africa. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Observatorio da Lingua Galega (OLG). 2008. Situación da Lingua Galega na Sociedade. Observación no Ámbito da Sanidade. Available online: https://www.observatoriodalingua.gal/sites/w_obslin/files/documentos/OLG_informe_sanidade.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2024).

- Odebunmi, Akin. 2010. Code selection at first meetings: A pragmatic analysis of doctor-client conversations in Nigeria. InLiSt 48: 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Odebunmi, Akin. 2013. Multiple codes, multiple impressions: An analysis of doctor-client encounters in Nigeria. Multilingua 32: 373–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, Sadhu Charan. 2006. Medicine: Science or art? Mens Sana Monogr 4: 127–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parlamento de Galicia. 1983. Lei 3/1983, do 15 de xuño, de normalización lingüística. Available online: https://www.parlamentodegalicia.es/sitios/web/BibliotecaLeisdeGalicia/Lei3_1983.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2024).

- Pawlikowska, Marta. 2020. El gallego y el castellano en contacto: Code-switching, convergencias y otros fenómenos de contacto entre lenguas. Ph.D. thesis. First published 2015. Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego, Łódz, Poland. First published 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pilnick, Alison, and Robert Dingwall. 2011. On the remarkable persistence of asymmetry in doctor/patient interaction: A critical review. Social Science & Medicine 72: 1374–82. [Google Scholar]

- Poplack, Shana. 1980. Sometimes I’ll start a sentence in Spanish y termino en Espanol?: Toward a typology of code-switching. Linguistics 18: 581–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poplack, Shana. 2013. Introductory comments by the author. Linguistics 51: 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prego Vázquez, Gabriela. 1997. Alianzas discursivas, alternancia de códigos y negociación de identidades en la Galicia rural. Interlingüística 7: 171–76. [Google Scholar]

- Prego Vázquez, Gabriela. 2010. Communicative styles of code-switching in service encounters: The frames manipulation and ideologies of ‘authenticity’ in institutional discourse. Sociolinguistic Studies 4: 371–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prys, Myfyr, Margaret Deuchar, and Gwerfyl Roberts. 2012. Measuring bilingual accommodation in Welsh rural pharmacies. In Multilingual Individuals and Multilingual Societies. Edited by Kurt Braunmüller and Christoph Gabriel. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 419–36. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, Gwerfyl Wyn, and Liz Paden. 2000. Identifying the factors influencing minority language use in health care education settings: A European perspective. Journal of Advanced Nursing 32: 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, Gwerfyl Wyn, Peter Reece Jones Fiona Elizabeth Irvine, Colin Ronald Baker Llinos Haf Spencer, and Cen Williams. 2007. Language awareness in the bilingual healthcare setting: A national survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies 44: 1177–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Tembrás, Vanesa. 2022. Code-Switching in Bilingual Medical Consultations (Galician-Spanish). Ph.D. thesis, Universität Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Yáñez, Xoán Paulo, and Hakan Casares Berg. 2003. The Corpus of Galicia/Spanish Bilingual Speech of the University of Vigo: Codes tagging and automatic annotation. Sociolinguistic Studies 4: 358–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servizo Galego de Saúde (SERGAS). 2015. Manual de Estilo dos Profesionais do Servizo Galego de Saúde: Recomendacións para Unha Comunicación Efectiva co Paciente. Available online: https://www.sergas.es/Calidade-e-seguridade-do-paciente/Documents/5/Manual_de_Estilo_Profesionais_gal%20definitivo_10_febreiro.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2024).

- Silva Valdivia, Benito. 2013. Galego e castelán: Entre o contacto e a converxencia. In Contacto de Linguas, Hibrididade, Cambio: Contextos, Procesos e Consecuencias. Edited by Eva Gugenberger, Henrique Monteagudo and Gabriel Rei-Doval. Santiago de Compostela: Consello da Cultura, pp. 289–317. [Google Scholar]

- Singo, Josephine. 2014. Code-switching in doctor-patient communication. NJHS 8: 48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Soto Andión, Xosé. 2014. Contacto y desplazamiento lingüístico en dos municipios del interior de Galicia. Vox Romanica 73: 218–46. [Google Scholar]

- Universidade de Santiago de Compostela (USC). 2021. A Boa Medicina. Available online: https://www.usc.gal/gl/servizos/area/normalizacion-linguistica/promover/campanas-dinamizacion-linguistica/boa-medicina (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- van Eemeren, Frans H., Bart Garssen, and Nanon Labrie. 2021. Argumentation between Doctors and Patients: Understanding Clinical Argumentative Discourse. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez Veiga, Nancy. 2003. Pero ya hablé gallego, lle dixen eu…: Análisis de un caso de alternancia de códigos en una situación bilingüe. ELUA. Estudios de Lingüística 17: 589–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickers, Caroline H., and Ryan Goble. 2018. Politeness and prosody in the construction of medical provider persona styles and patient relationships. Journal of Applied Linguistics & Professional Practice 11: 202–26. [Google Scholar]

- Wardhaugh, Ronald. 1992. An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. Blackwell Textbooks in Linguistics 4. Malden, Oxford and Victoria: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. First published 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, Nathan. 2018. Departing from Doctor-Speak: A Perspective on Code-Switching in the Medical Setting. Journal of General Internal Medicine 34: 464–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xunta de Galicia. 2004. Plan xeral de normalización da lingua galega. Xunta de Galicia. Available online: https://www.lingua.gal/c/document_library/get_file?folderId=1647062&name=DLFE-8928.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2024).

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).