Abstract

In this paper, we investigate zero-derived nouns based on irregular verbs in Greek. This is an under-explored area in Greek morpho-syntax, and in this paper, we will make three main contributions. First, we will discuss the fact that the overwhelming majority of these nouns are feminine, while neuter nouns are considerably less represented and masculine nouns are almost nonexistent. As feminine is taken to be the semantically marked gender in the case of animate nouns, asserting female sex, and neuter is argued to be the default gender in Greek for inanimates, the fact that zero abstract nouns are feminine is surprising. We will argue that feminine is the default in the case of zero derivation by exploiting an analysis of flavors of n. Second, we will show that, contrary to the findings in earlier literature, certain zero-derived nouns do have argument structure, similarly to their affixed counterparts. As not all zero-derived nouns have argument structure, we will appeal to complex head formation to explain the properties of those zero-derived nouns that have an eventive interpretation but do not surface with arguments. Finally, we will turn to an examination of the size of the domain that is nominalized. Since, in our cases, we observe root allomorphy conditioned by a nominal affix in the presence of a zero verbal head, we will suggest that Pruning is the mechanism that allows this.

1. Introduction

While there is extensive research on Greek nominalizations focusing on affixed derivations (see, e.g., Markantonatou 1992; Kolliakou 1995; and Alexiadou 2001, among others), in this paper we are concerned with a survey of zero-derived nouns based on irregular verbs in Greek. Zero-derived nouns pose at least three puzzles, which we will discuss here. First, the nominalizations of verbs listed as irregular in Holton et al. (1997) are mostly feminine, while neuter nouns are considerably less represented and masculine nouns are almost nonexistent. (1) offers some examples of feminine zero-derived nouns, where the affix is a declension class (DC) marker, Ralli (2000):

| (1) | a. | vaf-o | vaf-i |

| paint.1SG | paint.DCFEM | ||

| b. | trep-o | trop-i | |

| turn.1SG | turn.DCFEM | ||

| c. | thref-o | trof-i | |

| feed.1SG | food. DCFEM | ||

| d. | pin-a-o | pin-a | |

| hunger.ThV.1SG | hunger. DCFEM |

This is an interesting state of affairs, as this distribution mirrors the gender specification of affixed derived nouns: a large subset of deverbal nouns, especially action and result nouns ending in -s-iDC are feminine. In fact, several of the verbs listed as irregular in Holton et al. (1997) give -s- feminine nominalizations: ta-s-i ‘tendency’, kli-s-i ‘call’, the-s-i ‘position’, etc. This raises interesting questions about the representation of gender and the link between feminine gender and abstract nominal interpretation. Building on Kramer (2015) and Alexiadou (2017), we assume that the fact that deverbal nominalizations are gendered constitutes an argument that gender resides on the little n head, which hosts the nominalizing affixes, and is not a property of roots. The fact that in many Indo-European languages nominalizing affixes bear feminine gender has been widely discussed in historical linguistics (see, e.g., Luraghi 2013). For instance, as discussed in Luraghi (2013), in German deverbal abstract nouns take the feminine affix -ung. This fact is attributed to the emergence of a three-gender system that led to the following gender specification for nominal forms: neuter appears on mass nouns, masculine on individuated nouns, and feminine on abstract nouns (Vogel 2000; Weber 2001). The interesting finding of our investigation is that the same state of affairs holds for zero-derived nominals, and we will explore the reasons for this behavior.

Second, in the literature, zero-derived nominals are typically taken to lack argument structure, see Grimshaw (1990). We will show that this does not hold in Greek: zero-derived nominals may have argument structure, similarly to what has been argued for other languages. This in turn means that they may contain verbal layers and cannot simply be nominalizations of a root.

Third, we will demonstrate that looking at this particular class of nouns raises interesting questions concerning the size of the domain that is nominalized. Specifically, as we will see, there are several stem changes in the nominal derivations we are interested in, see, e.g., (1b) and (1c). Within the framework of Distributed Morphology, it is typically assumed that two morphemes must be linearly or structurally adjacent in order to influence each other (see, e.g., Embick 2010; Bobaljik 2012; Merchant 2015; Moskal 2015; Christopoulos and Petrosino 2018; and others). In our concrete cases, we would expect stem allomorphy to be conditioned by the nominalizing head, which is adjacent to the root. However, as we will show, one or more verbal heads may intervene; thus, we will suggest that Pruning (Embick 2010) is the mechanism that allows allomorphic triggering between elements that are structurally non-adjacent, as long as the nodes that intervene between the trigger and the target are realized as zero. Specifically, if zero nominals have argument structure, we must conclude that they are verb-derived, leaving Pruning as a mechanism to explain stem internal changes. As we will show, stem internal changes also occur in affixed nominalizations, under the condition that there is no overt verbalizer.

Our discussion is cast within the framework of Distributed Morphology, a framework that assumes that syntax operates on abstract morphemes and the realization (exponence) of these morphemes takes place after syntax (Bobaljik 2017, for discussion). As we will discuss in detail in Section 3, syntactic word formation manipulates acategorial roots that receive categorial specification in combination with so-called categorial heads, such as n and v, see Embick (2010).

The study of zero-derived nouns in English has received attention within Distributed Morphology in Arad (2003), who argued that zero-derived pairs offer evidence for two layers of word-formation: root-derived forms (hammer-hammer) and word-derived forms (nail-nail), see also Acquaviva (2009), but cf. Borer (2013). As far as we know, Greek zero-derived nouns have not been discussed in the literature at all. Moreover, the question of how their gender relates to their derivational history or whether they have argument structure has not been addressed, while some discussion of their root vs. word-derived nature is offered in Alexiadou (2009). This paper is a first attempt to fill this gap.

2. Greek (Zero) Derived Nominals

2.1. Greek Nominalizations from Irregular Verbs

To begin with, it is important to emphasize that Greek lacks zero-derived nouns of the English type: as in, e.g., Spanish (Fábregas 2014, p. 102), (2), the term zero-derived nouns in Greek applies to nouns that are derived from a verb in the absence of an overt nominalizer. As we see in (2), the Spanish verbal-nominal pair shares the same stem, but each form combines with a verbal vs. nominal thematic vowel, respectively. Specifically, in (2a), the stem combines with the verbal thematic vowel (ThV) and the result is a verb, while in (2b), the stem combines with the noun marker (NM) -a, and the result is a noun. Such markers cannot be analyzed as lexical categorizers: as Fábregas points out, in (2c) and (2d), we see that lexical verbalizers (vbz) can co-occur thematic vowels and lexical nominalizers (nmz) with noun markers:

| (2) | a. | abandon-oV |

| abandon.ThV | ||

| ‘abandon’ | ||

| b. | abandona-aN | |

| abandon.NM | ||

| ‘abandonment’ | ||

| c. | re-al-iz-a | |

| re-al-vbz.ThV | ||

| ‘realize’ | ||

| d. | mov-i-ment-o | |

| move.ThV.nmz.NM | ||

| ‘movement’ |

Similarly, the Greek pairs in (3) also share the same stem; the verbal forms surface with verbal agreement morphology, and they may contain ThVs (3a), while the nominal ones combine with DC markers. As in Spanish, the DC marker can appear next to the stem (3a) or after an overt nominalizer (3b):

| (3) | a. | pin-a-o | pin-a |

| hunger.ThV.1SG | hunger.DCFEM | ||

| b. | ana-li-o | ana-li-s-i | |

| prefix.solve.1SG | prefix.solve.nmz.DCFEM | ||

| ‘analyze’ | ‘analysis’ |

Let us now offer a more detailed survey of Greek (zero) nominalizations. As mentioned, we are concerned with nominalizations based on verbs that Holton et al. (1997, p. 262 ff.) classify as irregular. Greek has two verbal conjugations, and the basic distinction between the two relates to the position of the stress associated with the form of the 1st person present active tense: first conjugation verbs bear stress on the last syllable of their stem, e.g., gráf-o ‘write.1SG’, while second conjugation verbs bear stress on the last vowel, e.g., agap-ó ‘love.1SG’. These stems are used to form active and passive simple past as well as the perfective imperative, the perfect passive participle, and the non-finite forms used in the perfect tenses. According to Holton, Mackridge, and Philippaki-Warburton, verbs that do not conform to the general patterns of Greek verbal conjugation are considered irregular. In addition, second conjugation verbs that do not form the perfective stem with -is- (active) or -ith- (passive) and verbs that have irregular perfect passive participles are considered irregular.

Several of the verbs listed as irregular in Holton et al. (1997) have -s- nominalizations. -s- nominalizations are all feminine, suggesting that -s- realizes little n, see Alexiadou (2009, 2017).1 As we can see in (4), in several instances, an internal stem change can be observed, e.g., tino vs. tasi. Note that in the examples below, some of the verbs contain a thematic vowel which, following Spyropoulos et al. (2015), we analyze as signaling the presence of a v layer. It is interesting that the nominalization may also contain this vowel, as in (4a), or an alllomorph thereof, as in (4c). Others lack an overt realization of v, e.g., (4f). As we will discuss in Section 3, this in turn suggests that -s- nouns contain a v layer, which in some cases is realized as zero, so that the nominalizer can trigger a stem change across it:

| (4) | a. | apo-sp-a-o | ‘detach’ | apo-sp-a-s-i | ‘detachment’ |

| prefix.break.ThV.1SG. | prefix.break.ThV.nmz.DCFEM | ||||

| b. | kal-o | ‘call’ | kli-s-i | ‘call’ | |

| call.1SG | call.nmz. DCFEM | ||||

| c. | kata-fron-e-o ‘scorn’ | kata-fron-i-s-i | ‘scorning’ | ||

| prefix.know.ThV.1SG. | prefix.know.ThV.nmz.DCFEM | ||||

| d. | math-en-o | ‘learn’ | math/i-s-i | ‘learning’ | |

| learn.vbz.1SG | learn.ThV.nmz. DCFEM | ||||

| e. | ple-n-o | ‘wash’ | pli-s-i | ‘wash’ | |

| wash.vbz.1SG | wash.nmz. DCFEM | ||||

| f. | tin-o | ‘tend’ | ta-s-i | ‘tendency’ | |

| tend.1SG | tend.nmz.DCFEM | ||||

| g. | thet-o | ‘place’ | the-s-i | ‘position’ | |

| place.1Sg | place.nmz. DCFEM | ||||

As -s- nouns are always feminine, these are cases of gendered nominalizations of the type discussed in Kramer (2015) and Alexiadou (2017).

Several irregular verbs yield neuter nouns, (5), while there are also some masculine ones, which, however, are a minority. Such nominalizations can be both zero and affix-derived. In (5a), we see that often the nominal form contains a different verbalizer than the verb, e.g., kernao vs. kerasma. Originally, however, the verbalizer was -an-, which shifts to the allomorph -as- in the context of the nominalizer -m-. In (5b), we note that DC markers mostly attach directly to the stem.

| (5) | a. | Neuter2 | ||

| gdér-n-o ‘skin’ | gdár-sim-o ‘skinning’ | |||

| skin.vbz.1SG | skin.nmz. DCNEUT | |||

| gel-á-o ‘laugh’ | gél-io | ‘laugh’ | ||

| laugh.ThV.1SG | laugh.DCNEUT | |||

| ker-n-á-o ‘treat’ | kér-as-m-a | ‘treat’ | ||

| treat.vbz.ThV.1SG | treat.vbz.nmz. DCNEUT | |||

| pid-á-o ‘jump’ | píd-i-m-a ‘jump’ | |||

| jump.ThV.1SG | jump.ThV.nmz. DCNEUT | |||

| sp-á-o ‘break’ | sp-á-sim-o ‘breaking’ | |||

| break.ThV.1SG | break.ThV.nmz. DCNEUT | |||

| b. | Masculine | |||

| epen-é-o ‘praise’ | épen-os ‘praise’ | |||

| praise.ThV.1SG | praise.DCMASC | |||

| pon-á-o ‘feel pain’ | pón-os ‘pain’ | |||

| pain.ThV.1SG | pain. DCMASC | |||

| psél-n-o ‘chant’ | psal-m-ós ‘chant’ | |||

| chant.vbz.1SG | chant.nmz. DCMASC | |||

| psél-o ‘chant’ | ||||

| chant.1SG | ||||

Turning now to zero-derived feminine nouns derived from irregular verbs, we observe the following. First of all, none of these verbs contain a verbalizer. Second, they seem to belong to three groups, whereby the first group contains more zero forms. In (6), we see that the nominalization is marked by vowel gradation: the nouns formed contain -o-, while the verbal stem contains the vowel -e- or -i-. This pattern has been characterized in the literature as templatic (Pooth 2020), and is inherited from Proto-Indo-european. According to Pooth (2020), -o- is interpreted as a de-transitivizing marker. As we see, several of these base verbs contain prefixes:

| Verb | Noun | |||

| (6) | ana-val-o ‘postpone’ | ana-vol-i | ‘postponement’ | |

| prefix.throw.1SG | prefix.throw.DCFEM | |||

| vreh-o ‘rain’ | vroh-i | ‘rain’ | ||

| rain.1SG | rain. DCFEM | |||

| ek-leg-o ‘elect’ | ek-log-i | ‘election’ | ||

| prefix.say.1SG | prefix.say.DCFEM | |||

| apo-nem-o ‘award’ | apo-nom-i ‘award’ | |||

| prefix.take.1SG | prefix.take.DCFEM | |||

| klev-o ‘steal’ | klop-i | ‘theft’ | ||

| steal.1SG | steal. DCFEM | |||

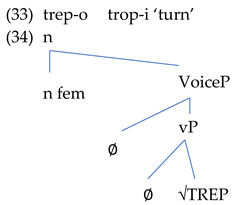

| trep-o ‘change’ | trop-i | ‘turn’ | ||

| turn.1SG | turn. DCFEM | |||

| tref-o ‘feed’ | trof-i | ‘food’ | ||

| feed.1SG | food. DCFEM | |||

| fthir-o ‘corrupt’ | fthor-a | ‘corruption’ | ||

| corrupt.1SG | corrupt. DCFEM | |||

Several other nominalizations do not show such a gradation and maintain the verbal stem vowel, as illustrated in (7):

| (7) | vosk-á-o ‘graze’ | vosk-í | ‘grazing’ |

| graze.ThV.1SG | graze.DCFEM | ||

| vut-á-o ‘dive’ | vút-a | ‘dive’ | |

| dive.ThV.1SG | dive.DCFEM | ||

| dips-á-o ‘am thirsty’ | díps-a | ‘thurst’ | |

| thurst.ThV.1SG | thurst.DCFEM | ||

| meth-á-o ‘get drunk’ | méth-i | ‘intoxication’ | |

| drunk.ThV.1SG | drunk.DCFEM | ||

| váf-o ‘paint’ | vaf-í | ‘paint’ | |

| paint.1SG | paint.DCFEM | ||

Finally, there are some examples where the nominal form contains a different vowel, namely the one that corresponds to the perfective verbal stem:

| (8) | févg-o | ‘I leave’ | fig-í ‘escape’ | efig-a ‘I escaped’ |

| leave.1SG | leave.DCFEM | left.1SG | ||

| her-ome ‘I am glad’ | har-á ‘cheerfulness’ | hárika ‘I was glad’ | ||

| glad.1SGNACT | cheer. DCFEM | cheered.1SGNACT | ||

Note that doublets are also found, whereby both a neuter and a feminine, zero or affixed, or a masculine and a neuter, affixed or zero nominalization, are possible. In such cases, e.g., (9a–b) and (10), the -m-/-sim- noun is interpreted as a process nominal, Alexiadou (2009), while the other forms may receive a more specialized meaning. In (9c), we have a feminine-neuter pair: the neuter noun contains the same stem as the verb, while the feminine noun is characterized by gradation. In (11), both nominalizations are zero-derived. However, while the feminine noun bears a meaning related to that of the corresponding verbs, the masculine noun bears an idiomatic/non-compositional interpretation:

| (9) | Verb | Feminine | Neuter | |

| a. | ké-o ‘burn’ | káf-s-i ‘burn’ | káp-sim-o ‘cutting’ | |

| b. | kóv-o ‘cut’ | kop-í ‘cut’ | kóp-sim-o ‘burning’ | |

| c. | févg-o | fig-í ‘leave’ | fevg-ió ‘leaving’ | |

| (10) | Verb | Masculine | Neuter | |

| víh-o ‘cough’ | víh-as ‘cough’ | vik-sim-o ‘coughing’ | ||

| (11) | Verb | Feminine | Massculine | |

| tém-n-o ‘cut’ | tom-í ‘cut, cutting’ | tóm-os ‘book’ | ||

| trép-o ‘turn’ | trop-í ‘turn’ | tróp-os ‘manner’ |

A further characteristic of zero-derived feminine nouns is that when they are derived from verbs that bear stress on the stem vowel, they show stress shift: the stress is on the final vowel of the derived noun, e.g., tropí, tomí, volí, vs. trépo, témno, válo, etc. According to Revithiadou (1999), Greek derivational affixes generally determine the stress of the derived word, which is expected if we take forms to contain a nominal categorizing head.

2.2. Derived Nominals and Argument Structure

Affixed derived nominals in Greek have been discussed in the literature in some detail. For instance, it has been shown that neuter -m--/sim- neuter nouns are argument supporting, see Kolliakou (1995), Alexiadou (2001, 2009). -M- and -sim- are taken to be allomorphic realizations of the same affix depending on the number of syllables of the stem: -sim- attaches to stems with one syllable, and -m- is the elsewhere form (Malikouti-Drachman and Drachman 1995). As argued for in Alexiadou (2009), -s- nouns behave like argument supporting nominals in the sense of Grimshaw (1990): not only are they eventive, as they can appear in eventive contexts (12a), but they can also appear together with an internal argument in the genitive, can be modified by aspectual modifiers such as frequent and license agentive by phrases similarly to -m-/-sim- nouns, (12c):3

| (12) | a. | i plisi kratai | 10 lepta | ||

| the wash lasts | 10 min | ||||

| b. | i sihni | apospasi | prosopiku | apo ti diikisi | |

| the frequent | detachment personel.GEN by the directorate | ||||

| the frequent detachment of personel | |||||

| c. | to kapsimo tu vivliu | apo to Jani | |||

| the burning the book.GEN by the John | |||||

Turning now to the question of whether or not zero-derived feminine nouns are expected to be argument-supporting, we note here that this has been controversially discussed in the literature. Grimshaw (1990) claimed that zero nouns lack argument structure and may only have result and simple event interpretations. A similar claim was made in Borer (2013), who looked at the properties of zero-derived nominals in English in some detail. According to Borer (2013, p. 332), contrasts such as the ones in (13) suggest that zero nouns are not argument-supporting. Specifically, as the examples in (13) show, zero-derived nouns in English do not allow the realization of the internal argument in an of-phrase and the external one in a by-PP, nor do they license aspectual PPs:

| (13) | a. | the salutation/*the salute of the officers by the subordinate |

| b. | the walking/*the walk of the dog for three hours |

The second argument Borer makes is that zero-derived nouns in English show a stress shift from verb final stress to nominal initial stress, as shown in (14), see also Kiparsky (1997):

| (14) | to tormént vs. the tórment |

Alexiadou and Grimshaw (2008), by contrast, claimed that only nouns derived from verbs license argument structure, so if it can be shown that zero-derived nominals are argument-supporting, then this means that they are verb-derived. This has been recently discussed at length in Iordăchioaia (2021, p. 244) for English, who challenges Borer’s view and shows that zero nominals do in fact license argument structure, see also Lieber (2016). After conducting searches in English corpora, Iordăchioaia (op.cit.) shows that, in fact, argument-supporting readings for certain zero nominals are possible, as we see in (25):

| (15) | a. | Trump defended his salute of one of Kim’s generals. (News On the Web Corpus) |

| b. | I have made the conscious choice not to exercise much beyond a brisky walk | |

| of the dog. (Corpus of Global Web-based English) |

Iordăchioaia then argues that the availability of argument structure licensing correlates with the root of the base verb: change of state verbs yield argument-supporting nominalizations. From this perspective, zero is just another potential realization of the nominalizer, as already alluded to in Alexiadou and Grimshaw (2008).

A further point made by Iordăchioaia (2021, p. 204) is that zero nouns derived from particle verbs may also license argument structure, irrespectively of the position of the particle:

| (16) | a. | outbreak of cholera |

| b. | buildout of renewable energy |

Crucially, then, the point Iordăchioaia makes for English is that not all zero nominals lack argument structure. We show here that this also holds for Greek. Applying Grimshaw’s diagnostics to Greek zero-derived nominals, we observe that certainly several of these, derived from both prefixed but also bare verbs, can be argument-supporting: as shown in (17), they appear together with an internal argument bearing genitive case, as well as a causative by-PP:

| (17) | a. | i anavoli ton eklogon apo tin kivernisi |

| the postponement of the elections by the government | ||

| b. | i fthora ton pragmaton apo to hrono | |

| the corruption of things by time |

However, not all zero-derived nominals are able to support argument structure. For instance, several zeros have eventive readings, e.g., vrohi ‘rain’, dipsa ‘thurst’, or trofi ‘food’, but lack argument structure.

To summarize this section: we have introduced three puzzles that we need to account for. First, the presence of feminine gender on zero nominals; second, the fact that they license argument structure; and third, the root allomorphy pattern observed in both zero and suffixed nominalizations, e.g., (4e) and (6).

3. Towards an Analysis

3.1. Theoretical Assumptions

Our analysis is cast within the framework of Distributed Morphology. Distributed Morphology adopts the idea that all words are internally complex as they are derived from combining roots with functional elements. Embick (2010, p. 21) defines the basic units of word formation as in (18) and (19):

| (18) | Functional Morphemes: Terminal nodes consisting of (bundles of) grammatical |

| features, such as [past] or [pl], etc.; these do not have phonological representations. | |

| (19) | Roots: Members of embers of the open-class or ‘lexical’ vocabulary: items such as |

| √CAT √OX, etc. |

Roots are taken to lack a category. Categorization is introduced in the syntax when the root combines with a so-called category-defining head, e.g., n, v, a.

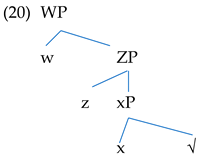

There are two main insights from Embick’s work that we appeal to. First of all, in a structure such as (20), x and z differ: x is root attached, while z attaches in a domain where it is not local to the root but attached in the outer domain.

According to Embick (2010), there are interpretational differences between root derived words and words that involve roots in combination with several other heads (21):

| (21) | Interpretation: The combination of root-attached x and the root might yield a |

| special interpretation. The heads x attached in the outer domain yield predictable | |

| interpretations. |

From this perspective, structures in which a category-defining head x is merged with a root are somehow special. By contrast, outer heads could not show root-specific interactions, as such heads are not present in the same cycle as the root. For example, an n in combination with a root can yield a variety of non-compositional interpretations. If, however, n combines with a verb, i.e., a root that has been categorized by a v head, then the interpretation of the nominalization is compositional, meaning that it carries the verbal meaning.

Related ideas were developed in Arad (2003, 2005), who was specifically concerned with zero derivation and proposed that roots may be assigned a variety of interpretations in different morpho-phonological environments, e.g., when a root combines with distinct categorizing heads. According to Arad, these interpretations, though retaining some shared core meaning of the root, are often semantically far apart from one another and are by no means predictable from the combination of the root and the word-creating head. However, once the root has merged with a category head and formed a word (n, v, etc.), its interpretation is fixed and will be carried along throughout the derivation. This locality constraint is universal; see also Anagnostopoulou and Samioti (2013, 2014) and Marantz (2013), who emphasize that categorizing heads fix the meaning of the root (see, e.g., Marantz 2013, p. 105), unless they are semantically empty, the semantic analogue to the visibility condition in (23) discussed right below.

There is a further mechanism that we will use, namely Pruning. This was introduced in Embick (2010) and is used in subsequent literature dealing with the question of which heads can act as triggers of allomorphy. In a structure, such as (22), a head y cannot trigger root allomorphy, as x intervenes, unless x is phonologically empty, as stated in the Visibility Condition in (23):

| (22) | [ y [ x [ √ ]]] |

| (23) | Features on node Y can condition allomorphy on a node X if Y is linearly adjacent |

| to X |

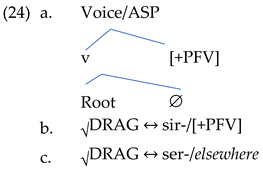

The basic insight of Embick’s Pruning operation is that it removes zero nodes from being relevant for allomorphy, allowing long-distance interactions that do not obey strict adjacency. Christopoulos and Petrosino (2018) employ Pruning to treat root allomorphy in the Greek verbal domain, see also Paparounas (2022). We will adopt their insights here. Specifically, the authors note that in Greek, if a verbal form shows root allomorphy, this form lacks an overt verbalizer. With verbs like serno ‘drag’, by contrast, where root-allomorphy is triggered by the feature [+PFV], (24b–c),4 allomorphy does take place under linear adjacency, as there is no overt intervener between the trigger and the target, as in (24a), where v is pruned:

Following Christopoulos and Petrosino (2018) as well as Paparounas’s (2022), we will treat root allomorphy in the nominal domain along the same lines: in a structure such as (25), n can trigger root allomorphy, but only if v and maybe other intervening heads receive zero exponence:

| (25) | [n [v [Root]]] |

The final assumption we will adopt is the view that gender is on n, see Kramer (2015) for a general such claim and Merchant (2014), Alexiadou (2017), Anagnostopoulou (2017), Markopoulos (2017, 2018), Sudo and Spathas (2020), and Adamson and Anagnostopoulou (2021) for Greek. As already mentioned, the fact that affixed nominalizations are gendered in Greek provides further support for this view. We have seen that all –s- nominals are feminine, while m/sim ones are neuter, and certain masculine forms bear the affix -m-, which is a case of accidental homophony. Moreover, feminine nominalizations all belong to Ralli’s (2000) DC3, while neuter ones belong to DC5 and DC7, and masculine ones to DC 1 and 2. While, as we will explain in the next section, gender is related to particular feature combinations on n, we assume that DC information is inserted post-syntactically on n (Kramer 2015 for a general such claim).

| (26) | [nGender/DC s/m/sim∅ [ ]] |

3.2. The Structure of Feminine Nouns

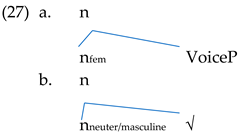

We begin with the argument structure properties. We propose two structures for zero nominals in Greek, (27a) and (27b). The two structures distinguish between argument supporting and non-argument supporting nominals in that the presence of a VoiceP signals the presence of argument structure, while the absence of verbal layers suggests root derivation:

(27a) does not differ from suffixed nominalizations discussed in Alexiadou (2001, 2009): Alexiadou noted the strong tendency to interpret -m- as ‘passive’. Taking the licensing of the agentive PP to be a reflex of the presence of Voice, Alexiadou et al. (2015), this suggests that Voice is contained in the structure of the nominals irrespectively of the presence of an affix (12) and (17).

However, we have seen that there are zero-derived nouns that support eventive readings, as can be seen by the fact that they permit eventive modification (28), but disallow argument structure, e.g., dipsa ‘thurst’:

| (28) | paratetameni dipsa |

| prolonged thurst |

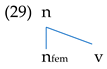

This type of nominal has been classified as a simple event nominal by Grimshaw (1990) and has been shown by subsequent work to generally allow event modification across languages, see e.g., Moulton (2014) for English and Alexiadou (2009) for Greek. Moulton’s take on these nominals can be summarized as follows: these are eventive root nominalizations. Roots may include an internal argument and an eventuality argument. In the case of simple event nominals, existential closure of the internal argument allows the noun to denote an eventuality. If, however, roots come without any arguments (as argued most notably in Borer 2013), the event reading present has to emerge from the presence of a v layer in their morpho-syntax, Alexiadou (2009). The analysis we would like to pursue to explain the difference between simple event nouns and argument supporting nouns is the following: argument supporting nominals amend themselves to what Wood (2021) calls the phrasal layering analysis, i.e., the nominalization is built on top of full verbal phrases, as in (27a). By contrast, simple event nominals are built by combining n and v directly, i.e., they are complex heads in the sense of Wood (2021): what is nominalized is simply a v, not a verbal phrase, hence arguments are not licensed, see (29).5

Turning now to the feminine gender question, we adapt Markopoulos’s (2017) ‘flavors of n’ analysis of Modern Greek, which views gender as the manifestation of different feature combinations on n. Specifically, Markopoulos takes the semantic features that are used cross-linguistically and categorize nouns to be different ways of nominalizing and assigning nouns to a particular cluster. The inventory of n in Greek includes, according to Markopoulos, both natural and arbitrary gender features, as shown in (30), where gender is basically the morphological realization of a particular n head:

| (30) | a. | n[+human, +fem] | Feminine |

| b. | n[+human, -fem] | Masculine | |

| c. | n[-human, +concrete] | Neuter | |

| d. | n[-human, -concrete] | Feminine |

(30d) is arbitrarily mapped to feminine exponents, capturing, as claimed in Markopoulos (2017),6 the correlation between abstract nouns and feminine gender. In his view, arbitrary gender features (±fem) are assigned by contextually specific rules to a closed class of nouns; thus, gender assignment in new word formations is predictable. Note that (30d) is also the combination that is unspecified and thus acts as the default. Further evidence for this comes from the observation made in Markopoulos that newly coined words with a non-concrete referent (e.g., a feeling) are assigned to feminine DC3, (31):

| (31) | ápla ‘comfort’ | dágla ‘drowsiness’ |

This is in sharp contrast to feminine on human nouns, which is semantically and morphologically more marked than masculine in Greek, as in several Indo-European languages, as evidenced by a variety of diagnostics (Merchant 2014; Alexiadou 2017; Sudo and Spathas 2020; Adamson and Anagnostopoulou 2021). By contrast, the default nature of feminine with abstract nouns seems to be related to the original function of the feminine affix in Indo-European. In the three-gender system of Indo-European, the original function of the feminine affix was to derive abstract nouns. This led to the following gender specification for nominal forms (Luraghi 2013): neuter appears on mass nouns, masculine on individuated nouns, and feminine on abstract nouns (see also Vogel 2000; Weber 2001). In fact, Luraghi (2013) points out that this is a more general strategy, not only found in Indo-European: for example, in Afro-Asiatic, feminine affixes also occur in abstract nouns and collectives.7

In the spirit of what is proposed in Acquaviva (2009) for Dutch, the selection of a particular n is sensitive to the root in the context of neuter and masculine nouns, while feminine is the default (32). Moreover, in the structure in (27b), root allomorphy (and allosemy) is expected, as n is local to the root.

| (32) | a. | [nNMZ: neuter] ⟷ ∅ / {ROOT}_______ (ROOT = Gel ‘laugh’... ) |

| b. | [nNMZ: masculine] ⟷ ∅ / {ROOT}_______ (ROOT = EPEN ‘praise’... ) | |

| c. | [nNMZ: feminine ] ⟷ ∅ |

Recall that we noted the templatic nature of several zero-derived forms, i.e., zero nominalization triggers root allomorphy (25). Typically, root allomorphy is negotiated locally, i.e., in the context of the categorizing head, obeying (23). However, on the basis of what we have argued in several cases, verbal layers intervene (34). To explain root allomorphy in this case, we will appeal to the role of Pruning which deletes nodes with ∅-exponence, see (25) above. As discussed in the previous section, Pruning removes zero nodes from the linearization statements, thus allowing nodes that normally do not interact to interact. Thus, structurally/linearly non-adjacent nodes can also interact, which explains vowel gradation. As Paparounas (2022) discusses in detail, Pruning is a last resort operation and is triggered under specific conditions. In fact, the conditioning of allomorphy here is very similar to the cases Christopoulos and Petrosino (2018), as well as Paparounas (2022), discuss for the verbal domain. n, being a phase head, defines the domain that is spelled out (Embick 2010).

Note here that in (34), it does not matter if the nominalizer itself has ∅-exponence or is realized by -s-, as long as v and Voice have ∅-exponence. Pruning will apply and trigger root allomorphy. On the other hand, these two layers intervene for selection and allosemy, and therefore feminine nouns are not sensitive to particular roots and do not give rise to non-compositional interpretations. This analysis crucially predicts that in the presence of an overt verbalizer, there should be no root allomorphy, and as far as we can tell, this is borne out, similarly to the verbal cases discussed in Christopoulos and Petrosino (2018):8

| (35) | kathar-iz-o | kathar-is-m-a |

| clean.vbz.1SG | clean.bvz.nmz.DCNEUT | |

| adi-az-o | adi-as-m-a | |

| empty.vbz.1SG | empty.vbz.nmz.DCNEUT |

4. Conclusions

In this paper, we discussed feminine zero-derived nouns, which raise interesting questions about the representation of gender and the link between feminine gender and nominal interpretation. The fact that deverbal nominalizations in Greek are gendered constitutes an argument that gender resides on little n, which hosts the nominalizing affixes and is not a property of roots. Abstract nouns bear feminine gender as a result of the emergence of a three-gender system (Luraghi 2013) that led to feminine gender as the default specification of abstract nouns. This characterization of feminine holds irrespectively of the overtly zero nature of the nominal affix. With concrete nouns, neuter is the default gender for inanimate nouns and masculine is the default for animate ones in languages like Modern Greek, as proposed by Markopoulos (2017) and argued for at length in Anagnostopoulou (2017) and Adamson and Anagnostopoulou (2021) on the basis of evidence from coordination resolution. We proposed a Distributed Morphology analysis by adopting the flavors of the n analysis in Markopoulos (2017). The data discussed further support the main claim of Distributed Morphology, according to which syntactic word formation manipulates acategorial roots that receive categorial specification in combination with so-called categorial heads, such as n and v. Greek zero-derived pairs offer further evidence for two layers of word formation: root-derived forms and word-derived forms.

In addition, we showed that zero-derived nominals license argument structure, and thus they may contain the same amount of verbal structure as their affixed counterparts. Furthermore, we looked at cases of root allomorphy across verbal layers with zero exponence and adopted Pruning to account for them.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A.A. and E.A., formal analysis. A.A. and E.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Deutsche Foschungsgemeinschaft grant AL 554/8-1 (Alexiadou) and by an Alexander von Humboldt Research Award Winners for Renewed Research Stays Grant (Anagnostopoulou). The APC was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) and the Open Access Publication Fund of Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to our three anonymous reviewers and our editors for their insightful comments towards improving this contribution. We are grateful to the participants of the Research Seminar at Humboldt University of Berlin for their comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | One could argue that -s- is a realization of perfective Aspect. However, as we see in the examples in (4), the stem of several nominal forms is not the one of their corresponding perfective verbal stem, e.g., pleno’wash’-eplina ’washed-PERF’, plisi ’washN’ or kalo ’callV’-kalesa ‘called-PERF’, klisi ‘callN’. | ||||||||||||

| 2 | Following Paparounas (2022), we analyze -n- in the verbal forms in (5) as a verbalizer. | ||||||||||||

| 3 | We note here that -s- nouns derived from unergative verbs do not give rise to argument supporting nominalizations, as discusssed Alexiadou (2001), and see Paparounas (2022), where (i) comes from, for a more recent discussion:

| ||||||||||||

| 4 | Note here that if -n- in ser-n-o is a verblalizer, as stated in note 2, its absence in the perfective makes Pruning possible. The authors assume that Voice and Aspect form a single node in Greek, formed via post-syntactic rebracketing, see Paparounas (2022) for arguments against this. | ||||||||||||

| 5 | We note here that Wood (2021) assumes that the complex head analysis is the input to both argument supporting and simple event nominals. | ||||||||||||

| 6 | We refer here to Markopoulos (2017) and not Markopoulos (2018), as the latter system does not employ (30d), i.e. [±concrete] is no longer part of the feature system of Greek nouns. However, for the set of data we are interested in, it seems that the former system makes the correct predictions. This is further motivated by the diachrony of Greek nouns: as discussed in Civilleri (2013), feminine derived nouns tend to have abstract semantics, while neuter ones tend to have concrete semantics. | ||||||||||||

| 7 | Interestingly, Markopoulos (2018) maintains that the [±concrete] feature distinction is relevant for e.g., Hebrew. | ||||||||||||

| 8 | Many thanks to an anonymous reviewer for pointing this out to us. | ||||||||||||

References

- Acquaviva, Paolo. 2009. Roots and lexicality in Distributed Morphology. Paper presented at 5th York-Essex Morphology Meeting, University of York, February 9–10; Issue 10. Available online: http://www.york.ac.uk/language/ypl/ypl2issue10/YPL_Issue_10_YEMM_Complete.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2022).

- Adamson, Luke, and Elena Anagnostopoulou. 2021. Interpretability and gender features in coordination: Evidence from Greek. To appear Proceedings of WCCFL 31. [Google Scholar]

- Alexiadou, Artemis, and Jane Grimshaw. 2008. Verbs, nouns and affixation. In SinSpeC (1): Working Papers of the SFB 732. Edited by Florian Schäfer. Stuttgart: University of Stuttgart, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Alexiadou, Artemis, Elena Anagnostopoulou, and Florian Schäfer. 2015. External Arguments in Transitivity Alternations: A Layering Approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alexiadou, Artemis. 2001. Functional Structure in Nominals: Nominalization and Ergativity. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Alexiadou, Artemis. 2009. On the role of syntactic locality in morphological processes: The case of (Greek) derived nominals. In Quantification, Definiteness and Nominalization. Edited by Anastasia Giannakidou and Monika Rathert. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 253–80. [Google Scholar]

- Alexiadou, Artemis. 2017. Gender and nominal ellipsis. In A Schrift to Fest Kyle Johnson. Edited by Nicholas LaCara, Keir Moulton and Ann-Michelle Tessier. Amherst: Linguistics Open Access Publications, University of Massachusetts at Amherst, pp. 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Anagnostopoulou, Elena, and Yota Samioti. 2013. Allosemy, idioms and their domains: Evidence from adjectival passives. In Syntax and its Limits. Edited by Rafaella Folli, Christina Sevdali and Robert Truswell. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 218–50. [Google Scholar]

- Anagnostopoulou, Elena, and Yota Samioti. 2014. Domains within words and their meanings: A case study. In The Syntax of Roots and the Roots of Syntax. Edited by Artemis Alexiadou, Hagit Borer and Florian Schäfer. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 81–111. [Google Scholar]

- Anagnostopoulou, Elena. 2017. Gender and defaults. In A Schrift to Fest Kyle Johnson. Edited by Nicholas LaCara, Keir Moulton and Ann-Michelle Tessier. Amherst: Linguistics Open Access Publications, University of Massachusetts at Amherst, pp. 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Arad, Maya. 2003. Locality constraints on the interpretation of roots: The case of Hebrew denominal verbs. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 21: 737–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arad, Maya. 2005. Roots and Patterns. Dordrecht: Kluwer. [Google Scholar]

- Bobaljik, Jonathan. 2012. Universals in Comparative Morphology: Suppletion, Superlatives and the Structure of Words. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bobaljik, Jonathan. 2017. Distributed Morphology. Oxford Research Encyclopedia: Linguistics. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borer, Hagit. 2013. Structuring Sense Vol. III Taking Form. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Christopoulos, Christos, and Roberto Petrosino. 2018. Greek root allomorphy without spans. In Proceedings of the 35th West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics. Edited by Wm G. Bennett, Lindsay Hracs and Dennis Ryan Storoshenko. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 151–60. [Google Scholar]

- Civilleri, Germana Olga. 2013. Abstract nouns. Encyclopedia of Ancient Greek Language and Linguistics, Edited by Georgios K. Giannakis. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embick, David. 2010. Localism and Globalism in Morphology and Phonology. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fábregas, Antonio. 2014. Argument structure and morphologically underived nouns in Spanish and in English. Lingua 141: 97–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimshaw, Jane. 1990. Argument Structure. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Holton, David, Peter Mackridge, and Irene Philippaki-Warburton. 1997. Greek: A Comprehensive Grammar of the Modern Language. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Iordăchioaia, Gianina. 2021. Compositional Structure and Idiosyncracy in Nominalizations. Berlin: Habilitationsshrift, Humboldt Universität zu Berlin. [Google Scholar]

- Kiparsky, Paul. 1997. Remarks on denominal verbs. In Argument Structure. Edited by Alex Alsina, Joan Bresnan and Peter Sells. Stanford: CSLI, pp. 473–99. [Google Scholar]

- Kolliakou, Dimitra. 1995. Definites and Possessives in Modern Greek: An HPSG Syntax for Noun Phrases. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, Ruth. 2015. The Morpho-Syntax of Gender. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lieber, Rochelle. 2016. English Nouns: The Ecology of Nominalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Luraghi, Silvia. 2013. Gender and word formation: The PIE gender system in cross-linguistic perspective. In Studies on the Collective and Feminine in Indo-European from a Diachronic and Typological Perspective. Edited by Sergio Neri and Roland Schuhmann. Leiden: Brill, pp. 199–231. [Google Scholar]

- Malikouti-Drachman, Angeliki, and Gaberell Drachman. 1995. Prosodic circumsription and Optimality Theory. In Studies in Greek Linguistics 1994. Thessaloniki: Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, pp. 143–61. [Google Scholar]

- Marantz, Alec. 2013. Phases and words. In Phases in the Theory of Grammar. Edited by Sook-Hee Choe. Seoul: Dong In, pp. 191–222. [Google Scholar]

- Markantonatou, Stela. 1992. The Syntax of Modern Greek Noun Phrases with a Derived Nominal Head. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Essex, Essex, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Markopoulos, Giorgos. 2017. Gender as n Realization: A Cross-Linguistic Study. London: Talk Given at the UCL Syntax reading group, February 8. [Google Scholar]

- Markopoulos, Giorgos. 2018. Phonological Realization of Morpho-Syntactic Features. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece. [Google Scholar]

- Merchant, Jason. 2014. Gender mismatches under nominal ellipsis. Lingua 151: 9–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchant, Jason. 2015. How much context is enough? Two cases of span-conditioned stem allomorphy. Linguistic Inquiry 46: 273–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskal, Beata. 2015. Limits on allomorphy: A case-study in nominal suppletion. Linguistic Inquiry 46: 363–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulton, Keir. 2014. Simple event nominalizations. In Crosslinguistic Investigations of Nominalization Patterns. Edited by Ilana Paul. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 119–44. [Google Scholar]

- Paparounas, Lefteris. 2022. Voice from Syntax to Syncretism. Ph.D. thesis, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Pooth, Roland. 2020. The original functions of Indo-European ablaut: Some remarks n Proto-Indo-European noun gradation and ablaut. New Trends in Indo-European Linguistics 1: 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Ralli, Angela. 2000. A feature-based analysis of Greek nominal inflection. Glossologia 11–12: 201–27. [Google Scholar]

- Revithiadou, Anthi. 1999. HeadmostAaccent Wins: Head Dominance and Ideal Prosodic form in Lexical Accentt Systems. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Leiden, Leiden, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Spyropoulos, Vassilios, Anthi Revithiadou, and Pheovos Panagiotidis. 2015. Verbalizers leave marks: Evidence from Greek. Morphology 25: 299–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudo, Yasutada, and Giorgos Spathas. 2020. Gender and interpretation in Greeek: Comments on Merchant (2014). Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics 5: 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, Petra. 2000. Nominal abstracts and gender in Modern German: A ‘quantitative’ approach towards the function of gender. In Gender in Grammar and Cognition. Edited by Barbara Unterbeck, Matti Rissanen, Terttu Nevalainen and Mirja Saari. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 461–93. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, Doris. 2001. Genus. Zur Funktion einer Nominalkategorie, exemplarisch dargestellt am Deutschen. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, Jim. 2021. Icelandic Nominalizations and Allosemy. Available online: https://ling.auf.net/lingbuzz/005004 (accessed on 15 June 2022).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).