High and Low Arguments in Northern and Pontic Greek

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Historical Background

2.1. The Ancient Greek Dative and Its Loss in Early Medieval Greek (5th–10th c. AD)

| (1) | δὸς ἐμοί [DAT] /ðˈos emˈy/ | “give me” (l. 20) |

| εἴρηκά σου [GEN] /ˈirikˌa su/ | “I have told you” (l. 20) | |

| σε [ACC] δίδω /se ðˈiðo/ | “I give you” (l. 24) | |

| P.Oxy. XIV 1683 (4th c. AD, Oxyrhynchos) | ||

| (2) | a-/i-masculines and feminines singular |

| ClGdat.sg [tɔ̂:i neanía:i]/acc.sg[tὸn neanía:n](<neanías “young man”[M]) | |

| → | LHellG/EMedG dat.sg [to neanˈia]/ acc.sg[ton neanˈia(n)] |

| ClG dat.sg [tɛ̂:i phɛ́:mε:i]/acc.sg [tɛ̀:n phɛ́:mε:n](<phɛ́:mε: “fame” [F]) | |

| → | LHellG/EMedG dat.sg [ti fˈimi]/ acc.sg [ti(n) fˈimi(n)] |

| (3) | a-/i-masculines and feminines plural |

| ClG dat.pl [toîs neaníais]/acc.pl [tù:s neanía:s](<neanías “young man” [M]) | |

| → | EMedG dat.pl [tys neanˈies]/ acc.pl [tus neanˈies] |

| ClG dat.pl [taîs phɛ́:mais]/acc.sg [tà:s phɛ́:ma:s](<phɛ́:mε: “fame” [F]) | |

| → | EMedG dat.pl [tes fˈimes]/ acc.pl [tas/tes fˈimes] |

| (4) | o-masculines, feminines and neuters singular |

| ClG dat.sg [tɔ̂:i dɔ́:rɔ:i]/nom/acc.sg [tὸ dɔ̂:ron] (<dɔ̂:ron “gift” [N]) | |

| → | LHellG/EMedG dat.sg [to ðˈoro]/ nom.acc.sg [to ðˈoro(n)] |

| (5) | neuters of non-personal pronouns |

| ClG dat.sg [autɔ̂:i]/nom/acc.sg [autó] (<autós/ autɛ́:/ autó “the same/this”) | |

| LHellG/EMedG dat.sg=acc.sg [aftˈo] |

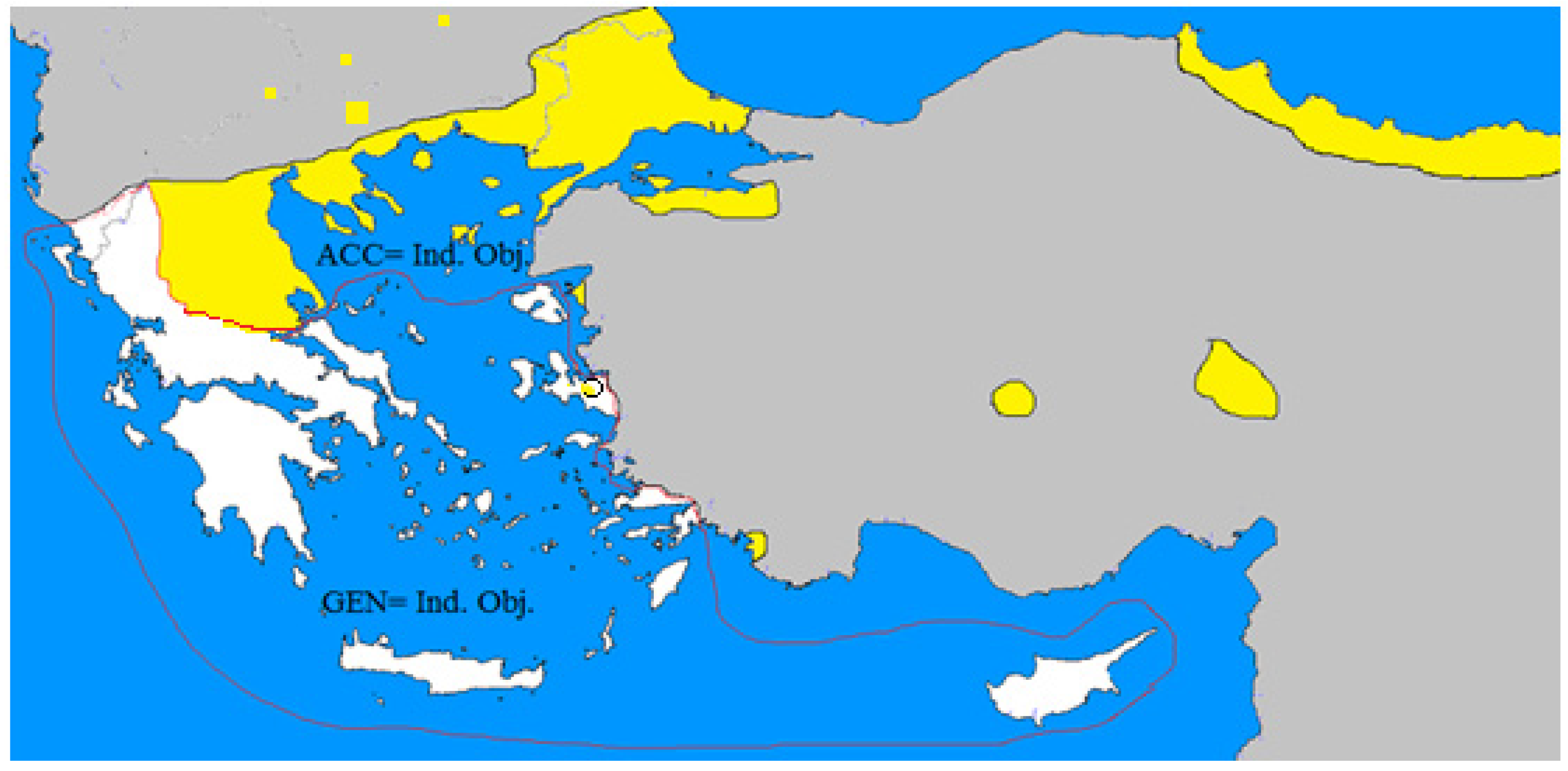

2.2. The Split between ACC=IO and GEN=IO Dialects

- Mani, Peloponnese: The variety of western inner Mani exhibits the parallel use of gen. and acc. forms in the first and second person and the genitive in every other domain, as with the rest of Peloponnesian. This variation could be attributed to three possible factors: (i) it could reflect an earlier stage of IO marking with free variation of the two cases, (ii) it could constitute an influence of the syncretic 1st and 2nd person acc/gen.pl mas/sas on the acc.sg me/se, or (iii) it could reflect contact with the Constantinopolitans (ACC=IO variety) who settled in south-eastern Peloponnese in the 15th c.

- North-eastern Rhodes and Kastellorizo: Despite the fact that the Dodecanesian varieties are GEN=IO, the north-eastern variety of Rhodes is ACC=IO and there is attestation of some ACC=IO constructions from Kastellorizo. This seems to be the result of settlements from or contact with the neighboring varieties that used to be spoken in Makri and Livisi in south-western Asia Minor (ACC=IO varieties).

- Siatista (and possibly other Thessalo-Macedonian varieties): Siatista employs genitive IOs for the pronominal clitics but the accusative with NPs. Manolessou and Beis (2006, p. 230) mentioned a structure with a nominal genitive IO, ου άντρας τ’ς λέει τ’ς υναίκας [u ˈadras ts lej ts inˈekas] “the husband tells his wife…”, but this clitic-doubling construction seems to reflect the influence of the case on the case of the noun, as such nominal genitive IOs have not been documented in our data. The origin of this complementary distribution of the two cases is attributed to the Aromanian substratum of the town, but this explanation is not satisfactory because similar structures are not found in other varieties with a possible Aromanian substratum, e.g., Naousa. An alternative explanation would be to attribute this feature to the settlement of speakers of Epirot GEN=IO varieties in the area.

2.3. Dative Alternation in Greek

3. Methodology

3.1. Classification of Structures Inherited from the Ancient Dative in Modern Greek (Expressed by the Genitive in GEN=IO and the Accusative in ACC=IO Dialects)

3.2. The Fieldwork

3.2.1. Location, Informants and Limitations

3.2.2. Collection of the Data

4. Northern Greek

4.1. The Data

4.1.1. Goal Ditransitives

4.1.2. Source Ditransitives

4.1.3. IO-like Benefactives/Malefactives

4.1.4. Experiencers

4.1.5. Affected Arguments

4.1.6. Comitatives

4.1.7. Motion Verbs with Goals

4.1.8. Motion Verbs with Sources

4.1.9. External Possessors

4.1.10. Ethical Datives

4.2. Summary

5. Pontic

5.1. The Data

5.1.1. Goal Ditransitive

5.1.2. Source Ditransitive

5.1.3. IO-like Benefactives/Malefactives

5.1.4. Experiencers

5.1.5. Affected Arguments

5.1.6. Comitatives

5.1.7. Motion Verbs (Goal)

5.1.8. Motion Verbs (Sources)

5.1.9. External Possessors

5.1.10. Ethical Datives

5.2. Summary

6. Discussion

6.1. Empirical Generalizations, Previous Analyses

- Goal, source, and benefactive/malefactive ditransitives, which we may call prototypical ditransitives, behave alike in both varieties.

- Clitic doubling is an extensively employed strategy in Northern Greek (but not across the board) and is entirely absent from Pontic.

- Clitic doubling in NG is obligatory in all NP-movement environments and optional in transitive environments, i.e., ditransitive structures and comitatives, exactly as in SMG in accordance with the generalization by Anagnostopoulou (2003).

- Pontic, which always has enclitics, differs from NG and SMG in always having a strict IO–DO order with clitics in the three prototypical environments that feature two clitics (ditransitives). In contrast, NG and SMG are allowed to switch the order of clitics from IO–DO to DO–IO in the contexts of enclisis (imperatives and gerunds; see the work of (Terzi 1999) for theoretical discussion).

- Pontic has a much more extensive use of prepositional alternations, not only with the predictable cases of goal and source ditransitives and benefactives/malefactives but also with experiencers as does SMG (Anagnostopoulou 1999).

- Ethical datives and external possessors consistently pattern together and set the two varieties apart (cf. Oikonomou et al. 2021, for relevant acquisition evidence). Pontic seems not to be able to license high arguments in these two structures.

6.2. Previous Literature

6.3. Towards an Analysis

| (6) | ?*To vivlio | charistike | tis Marias | ||

| The book-NOM award-Nact | the Maria-GEN | ||||

| apo | ton Petro | ||||

| from the Petros | |||||

| “?*The book was awarded Mary by Peter” | |||||

| (7) | To | vivlio | tis | charistike | (tis Marias) |

| The book-NOM Cl-GEN | award-Nact | the Maria-GEN | |||

| “The book was awarded to Mary” | |||||

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | All examples in Greek are given in phonetic transcription in the IPA. The stress accent is marked by the acute on the stressed vowel. Examples in Northern Greek mark the deletion of unstressed vowels with an apostrophe. The only phenomenon not phonetically transcribed is the deletion or the fusion of the final /n/ of the acc.sg of the definite article and the third person with the initial consonants of the following noun, e.g., /ton patera/ [to(m) batera] “the father”. We omitted this phonetic element so that there is no confusion between the masculine acc.sg. [to(n)] and the neuter [to]. |

| 2 | Apart from set expressions of ecclesiastical origin, which have always been based on ClG and HellG, e.g., ðόksa to θeό “glory to the Lord” [identical to an accusative]. |

| 3 | When variation exists (e.g., korákois instead of kόraksi), it seems either to be based on metrical preferences in verse texts or to arise from solecisms and poor knowledge of the archaistic language. |

| 4 | A small number of varieties only exhibit only one of the two features, e.g., there is only raising in Naousa, Macedonia and only deletion in Preveza, Epirus. Regarding the role of [u] in the evolution of the dative, an anonymous reviewer pointed out that the vowel /y/ survived as /y/ quite late, as late as 19th c. in some areas, and only subsequently evolved into /u/ or /i/ (as seen in recent discussions in (Mendez Dosuna 2021; Pantelidis 2021). In our view, while this has possibly affected the evolution of the dative, we do not regard it as a crucial factor. |

| 5 | Some conservative GEN=IO varieties (especially in southern Aegean and Cyprus) have replaced the ancient dative with the genitive, e.g., akluθó tu ɣéru “I follow the old man”. |

| 6 | The verbs listed in the table are standard SMG verbs that exemplify this class. In our fieldwork, we tried to use the standard verb or in its absence the dialectal cognate. Failing this, we used a synonym or ultimately moved to another verb from that group. |

| 7 | It could be that classes 4 and 5 are actually one and the same class, and we expect them to behave similarly. However, because the verbs in class 5 are not, strictly speaking, psychological, we have them in separate classes. |

| 8 | These verbs are characterized as comitatives because when they occur with a PP this PP is headed by the preposition “with” in contrast to the other “low applicative” verbs where the PP variant either surfaces with a “to” or “from” preposition. A practical criterion for drawing a distinction between high and low applicatives in Greek is the availability of a PP variant for the relevant constructions. We characterize those constructions where a PP variant is available as low applicatives, and by this criterion, benefactive verbs of the type “cook”/”buy” qualify as low applicatives similarly to experiencer verbs and affected constructions of the type seen in 4 and 5 where a “to” of “from” PP is possible. On the other hand, what we call high applicatives do not have the option of alternating with PPs. We are using the terms “high” and “low” not in the strict sense of, e.g., Pylkkänen ([2002] 2008), but rather as a descriptive way of drawing a distinction that, as we will see, is very crucial for the phenomena discussed in this paper. What we call a high applicative here always has an external possessor/affected/causer flavor (Schäfer 2008; Deal 2017; Bosse et al. 2012; Anagnostopoulou and Sevdali 2020) or an ethical dative flavor (Michelioudakis and Kapogianni 2013). |

| 9 | Most benefactives behave like IOs, while if there are benefactives that qualify as benefactives without falling in the category of either external possessors or experiencers/affected arguments, then they could be labeled as “free beneficiaries” and could be classified together with ethical datives. According to Michelioudakis (2012, p. 182), free benefactives are optional and “appear (even) with mono-eventive predicates, e.g., transitive and unergative verbs with simple event structures, e.g., “activities”, “statives”, and “achievements”. We believe that the class described by Michelioudakis should probably be reclassified into several distinct classes of the type illustrated in Table 2. If it nevertheless exists as a separate class, then it can be classified together with our last class, that of ethical datives, to which they are quite similar in many ways. Notice, though, that in the most conservative literature, ethical datives are reserved for datives encoding perspective, which do not surface as DPs at all, are typically first or second person, and occur very high in the clause. |

| 10 | We would like to thank the informants and also everyone that helped us locate the speakers and introduced us to them: Vassilios Spyropoulos (Assistant Professor, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens), Dr. Dimitris Gkaraliakos (Research Centre for Modern Greek Dialects, Academy of Athens), Dimitris Tsintzilidas, Ilias Giotas, Anastasios Dardas, Vasilis Paradisopoulos, Vasilis Terzidis, Paris Papageorgiou, and Pantelis Eleftheriadis. Information and data from our fieldwork can be found here: https://www.ulster.ac.uk/faculties/arts-humanities-and-social-sciences/communication-and-media/research/investigating-variation-and-change/corpusdata/fieldwork, accessed on 12 July 2022. |

| 11 | An anonymous reviewer urged us compare our findings with prior existing material from fieldwork on Pontic during the 19th and the 20th century. They claimed that this would make the results of the syntactic description more reliable, and this material may contain instances of all the construction types discussed in the paper. While we thank the reviewer for this suggestion, we must leave this comparison, useful as it may be, for another time. |

| 12 | An anonymous reviewer stated that it would be highly improbable that the clitic [ts] surfacing in the case of two consecutive accusative clitics is the feminine genitive singular [tis], as this would presuppose that (a) the genitive IO suddenly surface in an exclusively acc.-IO dialect and (b) the feminine generalize over the masculine. We agree with the reviewer and therefore we consider the second possibility as the most probable one. We include them both for the sake of completeness. For a thorough discussion on the expression of indirect objects in Medieval Greek, see the work of Lendari and Manolessou (2003). |

| 13 | Variation with respect to word order, number/gender/definiteness does not seem to play a role in the acceptability of any structures, although there is a preference for IO–DO structures and definite IOs. This is the same with source ditransitives, as seen in Section 4.1.2, and benefactives malefactives, as seen in Section 4.1.3. |

| 14 | e.g., *ðos aton ato “give him that”. A strong form is used instead, e.g., ðosa to atónene “give it to him”. |

| 15 | An anonymous reviewer madea point regarding the relationship between Pontic and Standard Greek. In particular, they claimed that Pontic has been cut off from the development of the main body of Greek since at least the 15th c. and would therefore not be expected to pattern with Standard MG or the Northern MG dialects in the matter of innovative syntactic phenomena, as some of the constructions examined here had not yet developed in Greek at the time of the split-off of Pontic. They further claimed that for the absence of construction X or Y to be characteristic of Pontic specifically, its date of appearance should first be determined. While we agree that the diachrony of these varieties is important, especially in relation to properties of Medieval Greek, this is beyond the scope of the present work. The reviewer specifically singled out the absence of clitic doubling, especially given that it is allegedly absent from Medieval Greek (as argued by Soltic 2013). While this is an important point, a systematic comparison between Medieval Greek and Pontic lies beyond the scope of this paper and must be left for future work. |

| 16 | It is interesting to note that dative alternation seems to be more limited for some speakers with experiencers, which may be paralleled in Cypriot Greek (Michelioudakis and Sitaridou 2012, p. 238) and the rare attestation of se with aréso in vernacular Medieval/early Modern texts. |

| 17 | The symbol ✓/✗ in the table above illustrates either variation among speakers or grammaticality and ungrammaticality in different environments, in particular whether the DO is a DP or a clause. |

References

- Anagnostopoulou, Elena. 1999. On experiencers. In Studies in Greek Syntax. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 67–93. [Google Scholar]

- Anagnostopoulou, Elena. 2003. The Syntax of Ditransitives: Evidence from Clitics. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, vol. 54. [Google Scholar]

- Anagnostopoulou, Elena. 2017. Defective intervention effects in two Greek varieties and their implications for φ-incorporation as Agree. In Order and Structure in Syntax II. Berlin: Language Science Press, p. 153. [Google Scholar]

- Anagnostopoulou, Elena, and Christina Sevdali. 2020. Two modes of dative and genitive case assignment: Evidence from two stages of Greek. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 38: 987–1051. [Google Scholar]

- Anagnostopoulou, Elena, Morgan Macleod, Dionysios Mertyris, and Christina Sevdali. forthcoming. Genitives and Datives with Ancient Greek three-place predicates. In The Place of Case in Grammar. Oxford: Oxford University Press, to appear.

- Angelopoulos, Nikos, and Dominique Sportiche. 2021. Clitic dislocations and clitics in French and Greek. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 39: 959–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Benvenuto, Maria Carmela, and Flavia Pompeo. 2012. Expressions of predicative possession in Ancient Greek: “εἶναι plus dative” and “εἶναι plus genitive” constructions. AION–Annali del Dipartimento di Studi Letterari, Linguistici e Comparati 1: 77–104. [Google Scholar]

- Bonet, Eulalía. 1991. Morphology after Syntax: Pronominal Clitics in Romance. Ph.D. dissertation, MIT, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Bortone, Pietro. 2010. Greek Prepositions from Antiquity to the Present. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bosse, Solveig, Benjamin Bruening, and Masahiro Yamada. 2012. Affected experiencers. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 30: 1185–230. [Google Scholar]

- Cardinaletti, Anna, and Michal Starke. 1999. The typology of structural deficiency. In Clitics in the Languages of Europe. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, pp. 145–233. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzikyriakidis, Stergios. 2010. Clitics in Four Dialects of Modern Greek: A Dynamic Account. Ph.D. thesis, University of London, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Condoravdi, Cleo, and Paul Kiparsky. 2002. Clitics and clause structure. Journal of Greek Linguistics 2: 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuervo, Maria Cristina. 2003. Datives at Large. Doctoral dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Deal, Amy Rose. 2017. External possession and possessor raising. In The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Syntax, 2nd ed. Hoboken: Wiley, pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Demonte, Violeta. 1995. Dative alternation in Spanish. Probus 7: 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriadis, Alexis. 1999. On Clitics, Prepositions and Case Licensing in Standard and Macedonian Greek. In Studies in Greek Syntax, Studies in Natural Language and Linguistic Theory. Edited by Artemis Alexiadou, Geoffrey Horrocks and Melita Stavrou. Dordrecht: Kluwer, vol. 43, pp. 95–112. [Google Scholar]

- Georgakopoulos, Athanasios. 2011. ΓνωσιακήπροσέγγισητηςσημασιολογικήςαλλαγήςτωνπροθέσεωντηςΕλληνικής: ηπερίπτωσητηςεἰς. Ph.D. thesis, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece. [Google Scholar]

- Horrocks, Geoffrey. 2010. Greek: A History of the Language and Its Speakers, 2nd ed. London: Wiley-Blackwell. First published 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Humbert, Jean. 1930. La disparition du datifengrec du Ièr au Xèm Siècle. Paris: Champion. [Google Scholar]

- Karatsareas, Petros. 2011. A study of Cappadocian Greek Nominal Morphology from a Diachronic and Dialectological Perspective. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Kisilier, Maxim, and Nikolaos Liosis. forthcoming. Τοωσενεοελληνικέςδιαλέκτους: δωδεκανησιακά, κρητικά, κατωιταλικά, μανιάτικα, τσακώνικα. Paper presented at the 9th International Conference on Modern Greek Dialects and Linguistic Theory, Global, Greece, January 18–20.

- Lendari, Tina, and Io Manolessou. 2003. H εκφορά του έμμεσου αντικειμένου στη μεσαιωνική ελληνική: εκδοτικά και γλωσσολογικά προβλήματα. Studies in Greek Linguistics 23: 394–405. [Google Scholar]

- Luraghi, Silvia. 2003. On the Meaning of Prepositions and Cases: The Expression of Semantic Roles in Ancient Greek. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Μanolessou, Io, and Stamatis Beis. 2006. Syntactic isoglosses in Modern Greek dialects. The case of the indirect object. In Modern Greek Dialects and Linguistic Theory. Patras: University of Patras, pp. 230–35. [Google Scholar]

- Markopoulos, Theodore. 2010. Case Overlap in Medieval Cypriot Greek: A socio-historical perspective. Folia Linguistica Historica 31: 89–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez Dosuna, Julian. 2021. The pronunciation of Ypsilon and related matters: A U-turn. In The Early Greek Alphabets: Origin, Diffusion, Uses. Edited by Robert Parker and Philippa Steele. Oxford: OUP, pp. 119–45. [Google Scholar]

- Mertyris, Dionysios. 2014. The Loss of the Genitive in Greek: A Diachronic and Dialectological Analysis. Ph.D. thesis, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Michelioudakis, Dimitris. 2012. Dative Arguments and Abstract Case in Greek. Ph.D. thesis, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Michelioudakis, Dimitris, and Eleni Kapogianni. 2013. Ethical Datives: A Puzzle for Syntax, Semantics, Pragmatics, and Their Interfaces. In Syntax and Its Limits. Edited by Raffaella Folli, Christina Sevdali and Robert Truswell. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 345–69. [Google Scholar]

- Michelioudakis, Dimitris, and Ioanna Sitaridou. 2012. Syntactic micro-variation in Pontic Greek: Dative constructions. In Variation in Datives: A Microcomparative Perspective. Edited by Beatriz Fernandez and Ricardo Etxepare. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 212–55. [Google Scholar]

- Minas, Konstantinos. 1994. H γλώσσα των δημοσιευμένων μεσαιωνικών ελληνικών εγγράφων της Κάτω Ιταλίας και της Σικελίας. Athens: Academy of Athens. [Google Scholar]

- Nevins, Andrew. 2007. The representation of third person and its consequences for person-case effects. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 25: 273–313. [Google Scholar]

- Nevins, Andrew. 2011. Multiple agree with clitics: Person complementarity vs. omnivorous number. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 29: 939–71. [Google Scholar]

- Oikonomou, Despoina, Elena Anagnostopoulou, and Vina Tsakali. 2021. The Development of DATIVE Arguments: Evidence from Modern Greek Clitics. Paper presented at the 45th Annual Boston University Conference on Language Development, Virtually, November 4–7; Somerville: Cascadilla Press, pp. 584–97. [Google Scholar]

- Pantelidis, Nikos. 2021. Aπό την ιστορία του ελληνικού φωνηεντισμού: Το «έκτο» φωνήεν. Paper presented at the ICGL 14, Patras, Greece, September 5–8; pp. 967–77. [Google Scholar]

- Preminger, Omer. 2019. The PCC, the No-Null-Agreement Generalization, and Clitic Doubling as Long Head Movement. Talk. Available online: https://omer.lingsite.org/files/Preminger-HPC-Tromso-handout.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Pylkkänen, Liina. 2008. Introducing Arguments. Linguistic Inquiry Monograph 49. Cambridge: MIT Press. First published 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Schäfer, Florian. 2008. The Syntax of (Anti-) Causatives: External Arguments in Change-of-State Contexts. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing, vol. 126. [Google Scholar]

- Soltic, Jorie. 2013. Clitic doubling in vernacular Medieval Greek. Transactions of the Philological Society 111: 379–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sportiche, Dominique. 1996. Clitic constructions. In Phrase Structure and the Lexicon. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 213–76. [Google Scholar]

- Stolk, Joanne V. 2017. Dative Alternation and Dative Case Syncretism in Greek: The Use of Dative, Accusative and Prepositional Phrases in Documentary Papyri. Transactions of the Philological Society 115: 212–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzi, Arhonto. 1999. Clitic combinations, their hosts and their ordering. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 17: 85–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, Werner. 1971. Formal frequency and linguistic change: Some preliminary comments. Folia Historica 5: 55–81. [Google Scholar]

| DATIVE PROPER | INSTRUMENTAL | LOCATIVE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| direct object | +animacy, +contact | -animacy | -animacy |

| indirect object | recipient, addressee, beneficiary/maleficiary, experiencer | - | - |

| possessive | Predicative/adnominal (+proximity) | - | - |

| prepositional | epí “on”: purpose | sún “with”: comitative | en “in” etc. |

| adverbial | agent, purpose | manner, instrument, cause | location (rare) |

| Class | Examples |

|---|---|

| /ðíno/ “give”, /léo/ “say”, /stélno/ “send”, /ðanízo/ “lend” etc. |

| /zitáo/ “ask from”, /krívo/ “hide”, /pérno/ “take from” etc. |

| /ftiáxno/ “make”, /maɣirévo/ “cook”, /aɣorázo/ “buy” etc. |

| /arési/ “appeals”, /fénome/ “seem” etc. |

| /aksízi/ “befits”, /lípi/ “misses”, /ftáni/ “suffices” |

| /miláo “speak (with)”, /miázo/ “look like”, /teriázo/ “match” etc. |

| /érxome/ “come”, /epistréfome/ “return” |

| /ksefévɣo/ “escape”, /krívome/ “hide from”, /kseɣlistráo/ “sneak away”. |

| /péfto/ “fall”, /krató/ “hold”, /ponáo/ “hurt”, /spáo/ “break” /kóvome/ “cut” |

| /filáo/ “kiss” /pandrévome/ “marry”, /steonoxoriéme/ “sadden”, /θimóno/ “get upset” |

| Clitics |

|

| Undoubled IO vs. Clitic doubling |

|

| Alternation |

|

| Passivization |

|

| Clitics |

|

| Undoubled IO vs. Clitic doubling |

|

| Alternation |

|

| Passivization |

|

| Clitics |

|

| Undoubled IO vs. Clitic doubling |

|

| Alternation |

|

| Passivization |

|

| Clitics |

|

| Undoubled IO vs. Clitic doubling |

|

| Alternation |

|

| Passivization |

|

| Clitics |

|

| Undoubled IO vs. Clitic doubling |

|

| Alternation |

|

| Passivization |

|

| Clitics |

|

| Undoubled IO vs. Clitic doubling |

|

| Alternation |

|

| Passivization |

|

| Clitics |

|

| Undoubled IO vs. Clitic doubling |

|

| Alternation |

|

| Passivization |

|

| Clitics |

|

| Undoubled IO vs. Clitic doubling |

|

| Alternation |

|

| Passivization |

|

| Clitics |

|

| Undoubled IO vs. Clitic doubling |

|

| Alternation |

|

| Passivization |

|

| Clitics |

|

| Undoubled IO vs. Clitic doubling |

|

| Alternation |

|

| Passivization |

|

| 1st Person | 2nd Person | 3rd Masculine | 3rd Feminine | 3rd Neuter | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | eme(n) em me(n) m | ese(n) es se(n) s | aton æton | aten atine(n) æten ætine(n) | at(o) a(t) æto æ(t) |

| Plural | ema(s) | esa(s) | ats | ats | ata |

| emasen(e) | esasen(e) | atsen(e) | atsen(e) | a | |

| ma(s) | sa(s) | æts | æts | æta | |

| masen(e) | sasen(e) | ætsen(e) | ætsen(e) | æ |

| Clitics |

|

| Undoubled IO vs. Clitic doubling |

|

| Alternation |

|

| Passivization |

|

| Clitics |

|

| Undoubled IO vs. Clitic doubling |

|

| Alternation |

|

| Passivization |

|

| Clitics |

|

| Undoubled IO vs. Clitic doubling |

|

| Alternation |

|

| Passivization |

|

| Clitics |

|

| Undoubled IO vs. Clitic doubling |

|

| Alternation |

|

| Passivization |

|

| Clitics |

|

| Undoubled IO vs. Clitic doubling |

|

| Alternation |

|

| Passivization |

|

| Clitics |

|

| Undoubled IO vs. Clitic doubling |

|

| Alternation |

|

| Passivization |

|

| Clitics |

|

| Undoubled IO vs. Clitic doubling |

|

| Alternation |

|

| Passivization |

|

| Clitics |

|

| Undoubled IO vs. Clitic doubling |

|

| Alternation |

|

| Passivization |

|

| Clitics |

|

| Undoubled IO vs. Clitic doubling |

|

| Alternation |

|

| Passivization |

|

| Clitics |

|

| Undoubled IO vs. Clitic doubling |

|

| Alternation |

|

| Passivization |

|

| Northern Greek | Pontic Greek | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clitic | Undoubl. DP | Cl. Doubl | PP alt | Pass/on | Clitic | Undoubl. DP | CL. Doubl | PP alt | Pass/on | |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ *U-DP | ✓ Strict order | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| ✓ | DO=CP ✓/DO=DP✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ Strict order | DO=CP ✓/DO=DP✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ Strict order | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | -- | ✓ | ✓/✗ | ✗ | ✓ | -- |

| ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | -- | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | -- |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | -- | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | -- |

| ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | -- | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | -- |

| ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | -- | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | -- |

| ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | -- | -- | ✗ | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| ✓ | -- | -- | -- | -- | ✗ | -- | -- | -- | -- |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Anagnostopoulou, E.; Mertyris, D.; Sevdali, C. High and Low Arguments in Northern and Pontic Greek. Languages 2022, 7, 238. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7030238

Anagnostopoulou E, Mertyris D, Sevdali C. High and Low Arguments in Northern and Pontic Greek. Languages. 2022; 7(3):238. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7030238

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnagnostopoulou, Elena, Dionysios Mertyris, and Christina Sevdali. 2022. "High and Low Arguments in Northern and Pontic Greek" Languages 7, no. 3: 238. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7030238

APA StyleAnagnostopoulou, E., Mertyris, D., & Sevdali, C. (2022). High and Low Arguments in Northern and Pontic Greek. Languages, 7(3), 238. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7030238