Interpretation of Imperfective Past Tense in Spanish: How Do Child and Adult Language Varieties Differ?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. The Spanish Contrast Pretérito Indefinido and Imperfecto

| (1) | Cog-ío | en | brazos | al | niño, | que | llor-ó. |

| Take-PI.3SG | in | arms | the | boy, | who | cry-PI.3SG2 | |

| ‘He picked up the boy, who (then) cried’ | |||||||

| (2) | Cog-ío | en | brazos | al | niño, | que | llor-aba |

| Take-PI.3SG | in | arms | the | boy, | who | cry-IMP.3SG | |

| ‘He picked up the boy, who was crying’ | |||||||

| (3) | Pedró | entr-ó. | María | llam-aba | por | teléfono. |

| Pedro | enter-PI.3SG | María | call-IMP.3SG | by | phone | |

| ‘Pedro came in. María was calling on the phone.’ | ||||||

| (4) | a. | El | teléfono | son-aba |

| The | phone | ring-IMP.3SG | ||

| ‘The phone was ringing’ | ||||

| b. | El | teléfono | son-ó. | |

| The | phone | ring-PI.3SG | ||

| ‘The phone rang’ | ||||

| (5) | El | niño | lav-ó | al | perro, | #pero | no | termin-ó |

| The | boy | wash-PI.3SG | the | dog, | #but | not | finish-PI.3SG | |

| ‘The boy washed up the dog, #but he didn’t finish’ | ||||||||

| (6) | El | niño | lav-aba | al | perro, | pero | no | termin-ó |

| The | boy | wash-IMP.3SG | the | dog, | but | not | finish-PI.3SG | |

| ‘The boy was washing the dog, but he didn’t finish’ | ||||||||

2.2. Grammatical Aspect in Child Language

2.3. Present Study

- (i)

- To what extent can Spanish 5-year-olds distinguish IMP from PI, and do they have an adult-like understanding of the progressive reading of IMP?

- (ii)

- If children do not demonstrate adult-like understanding of Spanish IMP, which property, or properties, of IMP create the acquisition challenge: the lack of a completion entailment, the resolution of anaphoricity, and/or the event-projection issue as related to agent intentionality?

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Design

3.3. Procedure and Stimuli

| (7) | Narrative context setting. |

| (8) | Test sentences: | ||

| a. | El niño hizo el puzle | (PI) | |

| “The boy made the puzzle” | |||

| b. | El niño hacía el puzle | (IMP) | |

| “The boy was making the puzzle” |

3.4. Coding

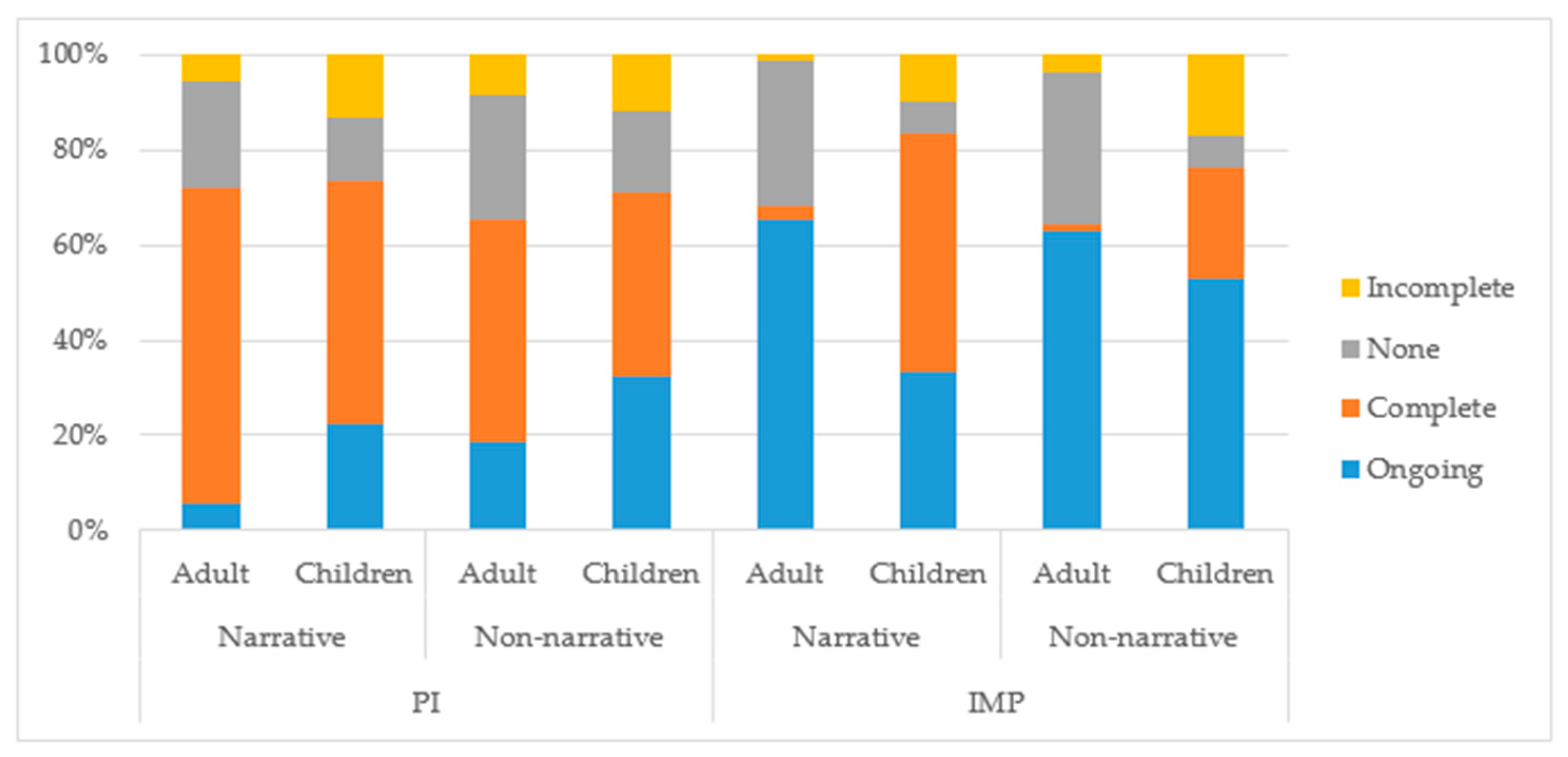

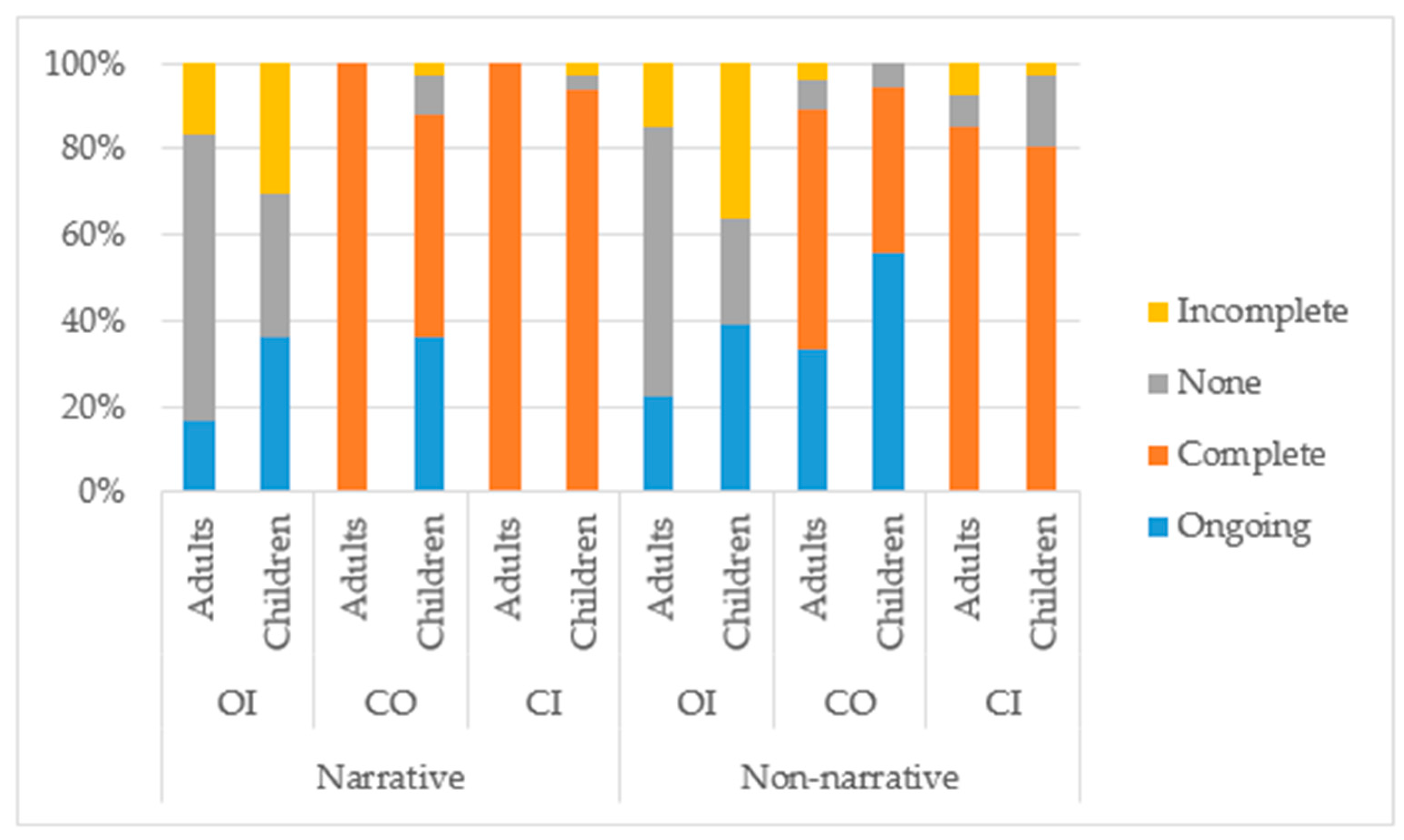

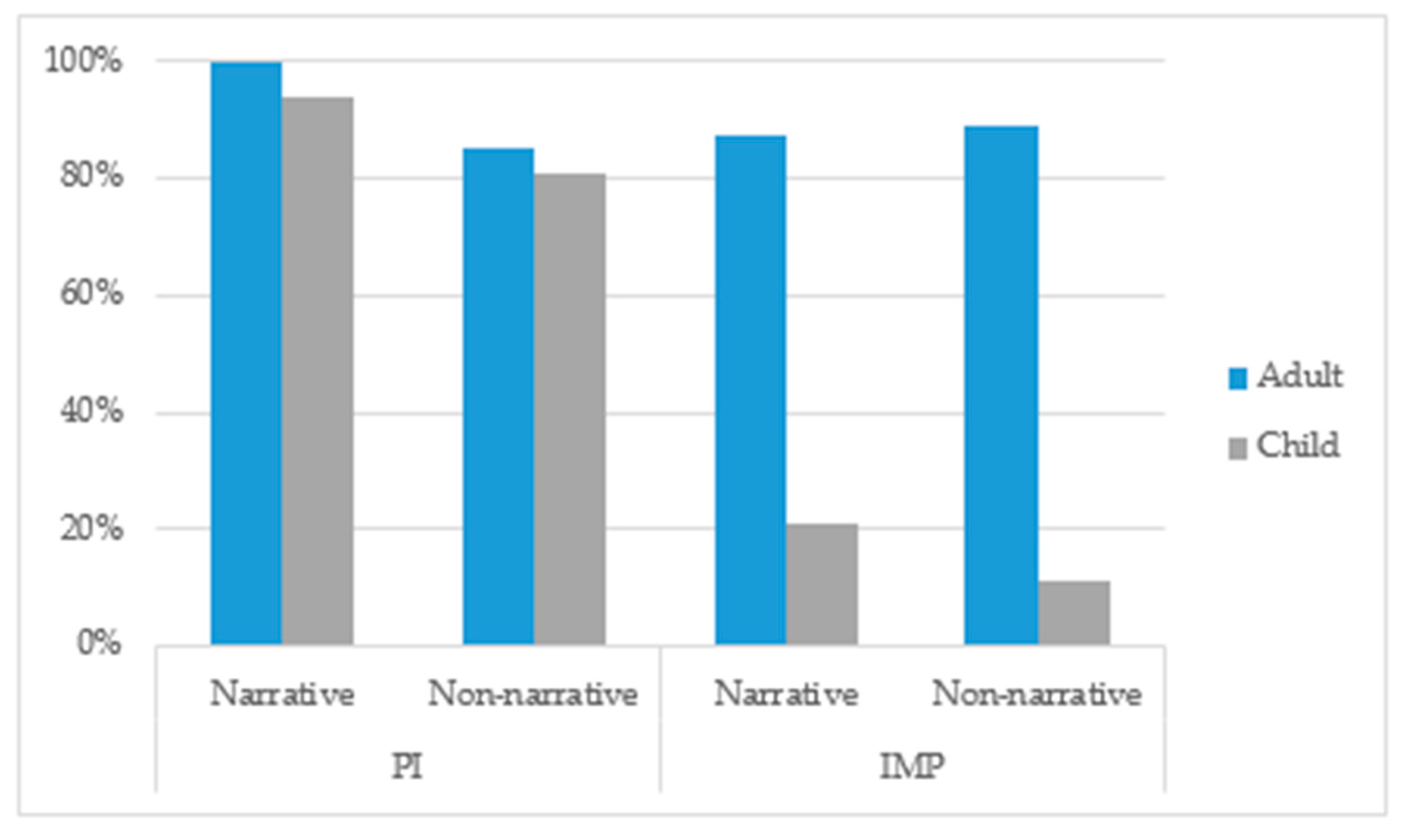

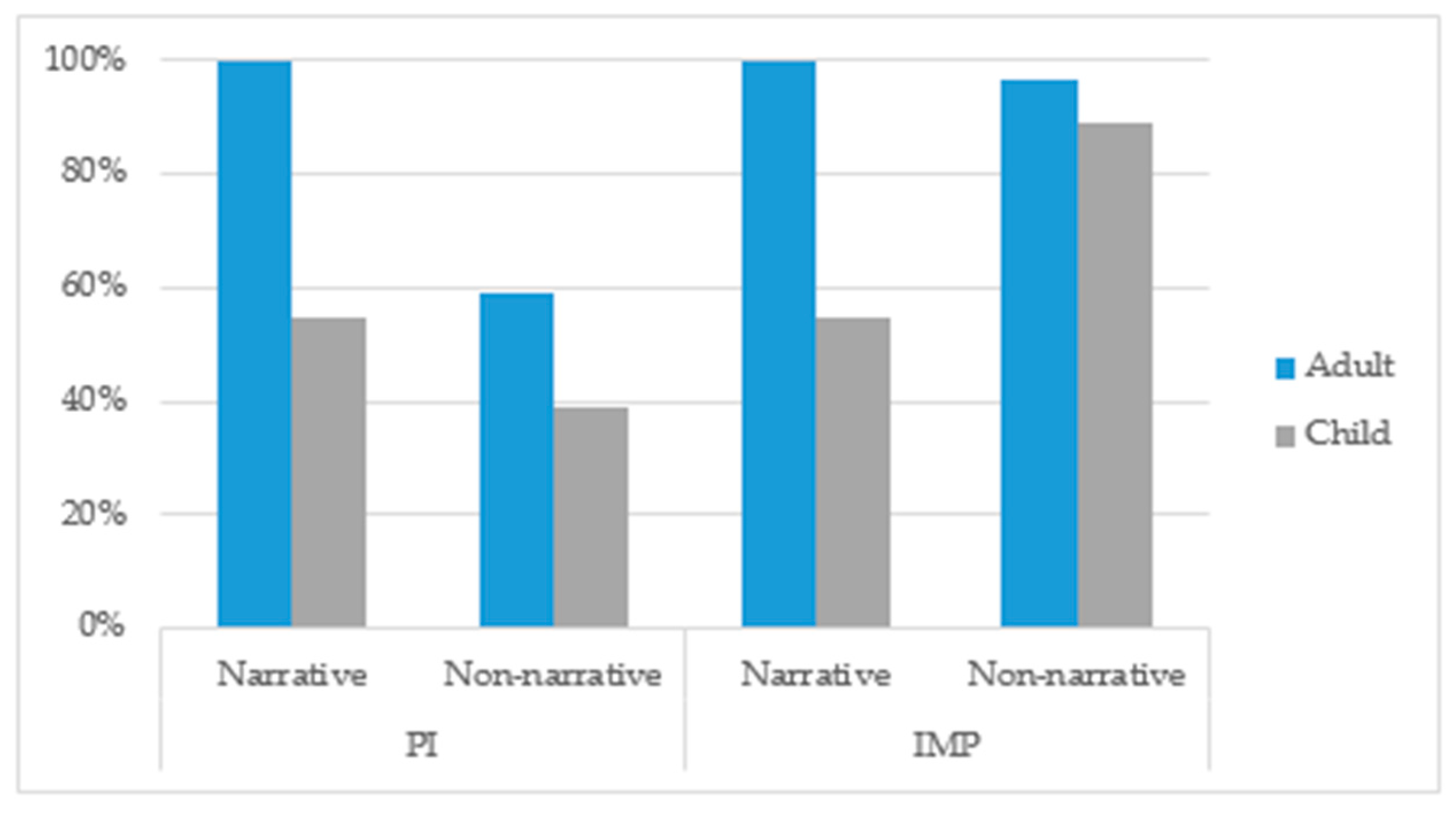

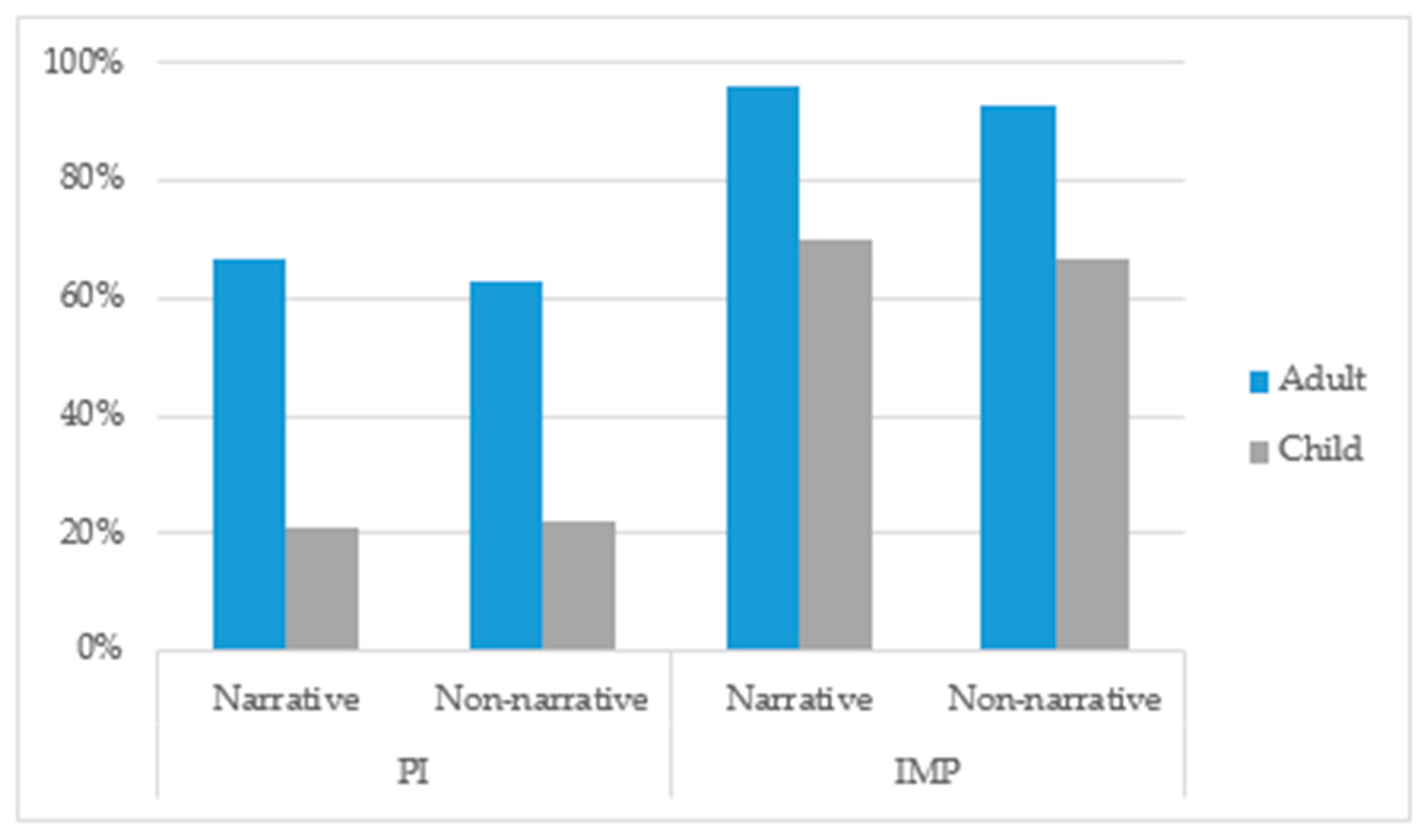

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Main Findings

5.2. Does the Absence of the Completion Entailment with IMP Pose an Acquisition Challenge?

5.3. Does Determining the Appropriate Reference Time for IMP Pose an Acquisition Challenge?

5.4. Does Event Projection Pose an Acquisition Challenge for IMP?

5.5. Does Ambiguity Pose an Acquisition Challenge for IMP?

5.6. Discourse Integration and Narrative Development

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| C–O Condition | C–I Condition | O–I Condition | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Session 1 | Hacer el puzzle Do the puzzle Lavar al perro Wash the dog Atarse el zapato Tie up the shoe | Dibujar el tigre Draw the tiger Cortarle la coleta a la niña Cut off the ponytail (to the girl) Doblar el papel Fold the paper | Construir el castillo Build the castle Comerse una zanahoria Eat up a carrot Recortar el círculo Cut out the circle |

| Session 2 | Leer el libro Read the book Escribir la carta Write a letter Comerse la sardina Eat up the sardine | Construir la torre Build the tower Dibujar una flor Draw a flower Cerrarse la chaqueta Tie up the jacket | Hacer un muñeco de plastilina Make a boy out of clay Borrar el círculo Erase the circle Descolgar la toalla Take the towel off the line |

| 1 | In the experimental setups in these studies, the events were presented in various forms: pictures showing two different situations (Weist et al. 1991); scenes acted out with props in front of the participants (Kazanina and Philips 2007); the result scenes of events that were acted out below the table (Wagner 2002); a series of pictures in a picture book presented with a story (van Hout 2005, 2007a, 2007b, 2008). These visual materials created either complete versus ongoing situations (Weist et al. 1991), or complete versus incomplete (interrupted) situations (the other studies). Given the nature of the task in these setups (assessing description or choosing a picture), imperfective aspect was expected to be acceptable, and indeed was for adults, for ongoing, incomplete, and complete versions of these events. See Section 2.2 for more details. |

| 2 | For easy reference, we have simplified the Leipzig Glosses convention and marked pretérito indefinido as PI and pretérito imperfecto as IMP. |

| 3 | This review of semantic theories of imperfective aspect is necessarily brief and is meant to introduce enough linguistic background to frame our acquisition study and describe the patterns in child language that we have found. It is not intended to be an exhaustive comparison of different theoretical approaches, nor do we suggest any conclusions as to which approach deals best with each property. |

| 4 | The term topic time in these approaches refers to the time that the story is about. We primarily use the term reference time in this paper, and occasionally topic time. For the purposes of the paper, the meaning of both terms is the same. |

| 5 | There is a parallel between the anaphoricity of definite and indefinite noun phrases and the anaphoricity of various tenses (Bennett and Partee 1972; Kamp and Rohrer 1983; Kamp and Reyle 1993; de Swart 1998, 2000; Vet 1999, a.o.). It would lead us too far afield to summarize this connection between nominal and temporal reference here. |

| 6 | According to Gehrke (2022) a fully compositional account of the discourse relations must integrate grammatical aspect with a number of other elements: the event type of the verb phrase, adverbials, the tense-aspect system in a given language (Gehrke discusses Russian and Czech), syntactic structure (subordinate vs. main clauses), and pragmatic reasoning based on the context or common sense. As Gehrke highlights, “a fully compositional account […] has to await future research” (Gehrke 2022, p. 14). In our study, we focus on the role of grammatical aspect, keeping everything else constant. |

| 7 | Following the tradition in Discourse Representation Theory (DRT), de Swart (1998) distinguishes three types of eventualities: state, process, event. These are similar to Vendler’s (1957) aspectual classes; his activity class is labeled in DRT as a process, and his two telic classes (accomplishments and achievements) are collapsed as events in DRT. |

| 8 | These approaches are called intensional as opposed to extensional approaches. Imperfective is defined in terms of the subinterval property: IMP(p) is true if the event e described by IMP(p) is part of an event e described by p. In intensional approaches, for an IMP to be true, it also must be associated to a complete event in at least one possible world (Bennett and Partee 1972). |

| 9 | The aspectual forms that were included in each language were: for Dutch, simple past (onvoltooid verleden tijd), present perfect (voltooid tegenwoordige tijd), and a past periphrastic progressive (aan-het construction) (van Hout 2007a, 2008); for Italian, imperfective past (imperfetto) and present perfect (passato prossimo) (van Hout and Hollebrandse 2001; van Hout 2008); for Polish, imperfective past (czas przeszb niedokonany) and perfective past (czas przeszb dokonany) (van Hout 2005, 2007b, 2008). We refer to the original papers for their motivation of these choices of perfective forms. The Italian data were originally presented in van Hout and Hollebrandse (2001). The current study used the same method; see Section 2 for more details. |

| 10 | |

| 11 | van Hout (2005) offers two other possible versions of an immature discourse grammar: (i) Children do not know or apply any discourse rules in the semantics-pragmatics interface and instead order events in a non-verbal manner (according to what seems most plausible to them); (ii) Children have discourse rules, but these are different from the adult rules. We will not discuss these other explanations further here. |

| 12 | In Kazanina and Philips’ (2007) experimental setting, there was exactly one reference time. This was different from van Hout’s (2005) setting that involved a story introducing a series of times. See Section 2 for more details, as the current study used Van Hout’s setup, and see Section 4 for detailed discussion. |

| 13 | Note that the conditions and the tasks were different across the various studies. While a sentence-picture verification task measures acceptance as well as rejection, a picture-selection task targets preferred interpretations (van Hout et al. 2010). For a detailed discussion of this issue for the acquisition of aspect, see García-del-Real et al. (2014). |

| 14 | In both settings, this question was formulated with PI or IMP, parallel with the tense in the test sentence. We thought that the use of the IMP in the preceding question would favor the progressive reading of the form in the test sentence. |

| 15 | Statistical analyses revealed no influence of item order (for PI: children χ2 = 2.968; p > 0.05 and adults χ2 = 0.629; p > 0.05; for IMP: children χ2 = 0.696; p > 0.05 and adults χ2 = 0.629; p > 0.05) or the order of sessions (for PI: children χ2 = 0.287; p > 0.05 and adults χ2 = 0.629; p > 0.05; for IMP: children χ2 = 0.001; p > 0.05 and adults χ2 = 0.993; p > 0.05). |

| 16 | Except for PI in the narrative setting, where adults, instead of always choosing the complete picture, sometimes chose the ongoing one. The same pattern was revealed for the children. This deviation from the target response will be discussed in Section 5. |

| 17 | This was mentioned in the informal feedback from adults after testing. |

| 18 | We thank Bert Le Bruyn, one of the editors of this special volume, for this insight. |

| 19 | Interestingly, agent intentionality played a (small) role for the adults with PI in the C–O condition in the non-narrative setting. Since the picture of a complete situation does not indicate if the character in the picture had performed the action, the adults sometimes preferred the ongoing situation for PI, remarking that there, they could be sure that the agent was indeed doing the action. |

| 20 | Martin et al.’s (2020) explanation also covers two other types of non-adult-like interpretation patterns of aspect interpretation that are not pertinent to the current discussion here; thus, their explanation has a wider coverage than just the challenge with imperfective aspect. |

| 21 | Grønn (2008) argues that the disambiguation of Russian imperfective aspect towards an imperfective reading in the adult grammar is easier in the presence of an explicit element providing a discourse referent for the reference time. When no such explicit element is present, the underspecified interval corresponds to “the whole past preceding the reference time” (Grønn 2008, p. 11), favoring a perfective interpretation. To obtain an imperfective reading where the reference time t refers to “some point in the past” (Grønn 2008, p. 11), accommodation is required. |

References

- Alarcos Llorach, Emilio. 1994. Gramática de la Lengua Española. Madrid: Espasa Calpe. [Google Scholar]

- Arche, María J. 2014. The construction of viewpoint aspect: The imperfective revisited. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 32: 791–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asher, Nicholas. 1992. A default, truth conditional semantics for the progressive. Linguistics and Philosophy 15: 463–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, Andrés. 1841. Análisis Ideológica de los Tiempos de la Conjugación Castellana. [Ed. 1951]. Caracas: Ministerio de Educación. [Google Scholar]

- Bello, Andrés. 1847. Gramática de la Lengua Castellana Destinada al Uso de los Americanos. [Ed. 1981]. Santa Cruz de Tenerife: Instituto Universitario de Lingüística. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, Michael, and Barbara H. Partee. 1972. Toward the logic of tense and aspect in English. In Compositionality in Formal Semantics: Selected Papers of Barbara Partee. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 59–109, Re-published in 2004 in Partee B. [Google Scholar]

- Berthonneau, Anne-Marie, and Georges Kleiber. 1993. Pour une nouvelle approche de l’imparfait: L’imparfait, un temps anaphorique méronomique. Langages 112: 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertinetto, Pier Marco. 1986. Tempo, Aspetto E Azione Nel Verbo Italiano. Firenze: Accademia della Crusca. [Google Scholar]

- Bronckart, Jean-Paul, and Hermine Sinclair. 1973. Time, tense and aspect. Cognition 2: 107–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, Laura, Maria J. Arche, and Florence Myles. 2017. Spanish Imperfect revisited: Exploring L1 influence in the reassembly of imperfective features onto new L2 forms. Second Language Research 33: 431–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowty, David. 1979. Word Meaning and Montague Grammar. Dordrecht: Reidel. [Google Scholar]

- Fábregas, Antonio. 2015. Imperfecto and indefinido in Spanish: What, where and how. Borealis 4: 1–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feagans, Lynne. 1980. Children’s understanding of some temporal terms denoting order, duration, and simultaneity. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 9: 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Fernández, Luis. 2000. La Gramática de los Complementos Temporales. Madrid: Visor. [Google Scholar]

- García Fernández, Luis. 2004. El pretérito imperfecto: Repaso histórico y bibliográfico. In El Pretérito Imperfecto. Edited by Luis García Fernández and Bruno Camus Bergareche. Madrid: Gredos, pp. 13–96. [Google Scholar]

- García-del-Real, Isabel, and Maria José Ezeizabarrena. 2012. Comprehension of grammatical and lexical aspect in early Spanish and Basque. In Selected Proceedings of the Romance Turn IV Workshop on the Acquisition of Romance Languages. Edited by Sandrine Ferré, Philippe Prévost and Laurie Tuller. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 82–103. [Google Scholar]

- García-del-Real, Isabel, Angeliek van Hout, and María José Ezeizabarrena. 2014. Comprehension and production of grammatical aspect in child Spanish: Semantics vs. pragmatics. In Selected Proceedings of the 5th Conference on Generative Approaches to Language Acquisition North America (GALANA 2012). Edited by Chia-Ying Chu, Caitlin E. Coughlin, Beatriz López Prego, Utako Minai and Annie Tremblay. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 99–110. [Google Scholar]

- Gehrke, Berit. 2022. Differences between Russian and Czech in the use of aspect in narrative discourse and factual contexts. Languages 7: 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, Alessandra, and Fabio Pianesi. 1998. Tense and Aspect: From Semantics to Morphosyntax. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grønn, Atle. 2008. Russian aspect as bidirectional optimization. In Studies in Formal Slavic Linguistics: Contributions from FDSL 6.5. Edited by Franc Lanko Marušić and Rok Zaucer. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, pp. 121–37. [Google Scholar]

- Hickmann, Maya. 2002. Children’s Discourse: Person, Space and Time across Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- van Hout, Angeliek. 2005. Imperfect imperfectives: On the acquisition of aspect in Polish. In Aspectual Inquiries. Edited by Paula Kempchinsky and Roumyana Slabakova. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 317–44. [Google Scholar]

- van Hout, Angeliek. 2007a. Optimal and non-optimal interpretations in the acquisition of Dutch past tenses. In Proceedings of the 2nd Conference on Generative Approaches to Language Acquisition North America (GALANA). Edited by Alyona Belikova, Luisa Meroni and Mari Umeda. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 159–70. [Google Scholar]

- van Hout, Angeliek. 2007b. Acquisition of aspectual meanings in a language with and a language without morphological aspect. In 31st BUCLD Proceedings Supplement. Edited by Heather Caunt-Nulton, Samantha Kulatilake and I-hao Woo. Somerville: Cascadilla Press. [Google Scholar]

- van Hout, Angeliek. 2008. Acquiring perfectivity and telicity in Dutch, Italian and Polish. Lingua 118: 1740–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hout, Angeliek. 2018. On the acquisition of event culmination. In Semantics in Language Acquisition. Edited by Kristen Syrett and Sudha Arunachalam. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 95–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hout, Angeliek, and Bart Hollebrandse. 2001. On the acquisition of the aspects in Italian. In The Proceedings of SULA: The Semantics of Under-Represented Languages in the Americas. Edited by Ji-Yung Kim and Adam Werle. UMOP 25. Amherst: GLSA, pp. 111–20. [Google Scholar]

- van Hout, Angeliek, Kaitlyn Harrigan, and Jill de Villiers. 2010. Asymmetries in the acquisition of definite and indefinite NPs. Lingua 120: 1973–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hout, Angeliek, and COST A33 Consortium. Forthcoming. Crosslinguistic Acquisition of Perfective-Imperfective Aspect: Universal and Language-Specific Patterns across 12 Child Languages, Ms. University of Groningen: In preparation.

- Kail, Michèle, and Maya Hickmann. 1992. French children’s ability to introduce referents in narratives as a function of mutual knowledge. First Language 12: 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamp, Hans, and Christian Rohrer. 1983. Tense in texts. In Meaning, Use and Interpretation of Language. Edited by Rainer Bäuerle, Christoph Schwarze and Arnim von Stechow. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 250–69. [Google Scholar]

- Kamp, Hans, and Uwe Reyle. 1993. From Discourse to Logic: Introduction to Modeltheoretic Semantics of Natural Language, Formal Logic and Discourse Representation Theory. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Karmiloff-Smith, Annette. 1979. A Functional Approach to Child Language: A Study of Determiners and Reference. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Karmiloff, Kyra, and Annette Karmiloff-Smith. 2001. Pathways to Language: From Fetus to Adolescent (The Developing Child). Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kazanina, Nina, and Colin Philips. 2007. A developmental perspective on the imperfective paradox. Cognition 105: 65–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenny, Anthony. 1963. Action, Emotion and Will. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, Wolfgang. 1994. Time in Language. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Landman, Fred. 1992. The progressive. Natural Language Semantics 1: 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonetti, Manuel. 2004. Por qué el imperfecto es anafórico. In El Pretérito Imperfecto. Edited by Bruno Camus and Luis García. Madrid: Gredos, pp. 481–507. [Google Scholar]

- Leonetti, Manuel. 2018. Temporal anaphora with Spanish Imperfecto. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 47: 391–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lidz, Jeffrey, Snyder William, and Joe Pater, eds. 2016. The Oxford Handbook of Developmental Linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, Fabienne, Hamida Demirdache, Isabel García-del-Real, Angeliek van Hout, and Nina Kazanina. 2020. Children’s non-adultlike interpretations of telic predicates across languages. Linguistics 58: 1447–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, Gijs, Gert-Jan Schoenmaker, Olaf Hoenselaar, and Helen de Hoop. 2022. Tense and aspect in a Spanish literary work and its translations. Languages 7: 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichenbach, Hans. 1947. Elements of Symbolic Logic. New York: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Rojo, Guilllermo. 1974. La temporalidad verbal en español. Verba 1: 68–149. [Google Scholar]

- Rojo, Guillermo, and Alexandre Veiga. 1999. El tiempo verbal: Los tiempos simples. In Gramática Descriptiva de la Lengua Española. Edited by Ignacio Bosque and Violeta Demonte. Madrid: Espasa, pp. 2867–935. [Google Scholar]

- de Swart, Henriëtte. 1998. Aspect shift and coercion. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 16: 347–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Swart, Henriëtte, and Henk J. Verkuyl. 1999. Tense and Aspect in Sentence and Discourse. Utrecht: ESSLLI. [Google Scholar]

- de Swart, Henriëtte. 2000. Tense, aspect and coercion in a cross-linguistic perspective. In Proceedings of the Berkeley Conference on Formal Grammar. Edited by Miriam Butt and Tracy Holloway King. Berkeley: CSLI Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Syrett, Kristen, and Sudha Arunachalam, eds. 2018. Semantics in Language Acquisition. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Vendler, Zeno. 1957. Verbs and times. Philosophical Review 66: 143–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vet, Co. 2000. Référence temporelle, aspect verbal et les dichotomies massif/comptable et connu/nouveau. In Référence Temporelle et Nominale. Actes du 3ème Cycle Romand des Sciences du Langage. Edited by Jacques Moeschler and Marie-Jose Bégelin. Bern: Peter Lang, pp. 146–66. [Google Scholar]

- Vet, Co. 1999. Les temps verbaux comme expressions anaphoriques: Chronique de la recherche. Travaux de Linguistique 39: 113–30. [Google Scholar]

- Vinnitskaya, Inna, and Ken Wexler. 2001. The role of pragmatics in the development of Russian aspect. First Language 21: 143–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Stutterheim, Christiane, Ute Halm, and Mary Carroll. 2012. Macrostructural principles and the development of narrative competence in L1 German: The role of grammar (8–14-year-olds). In Comparative Perspectives on Language Acquisition: A Tribute to Clive Perdue. Edited by Marezna Watorek, Sandra Benazzo and Maya Hickmann. Bristol: Multilingual Matters, pp. 559–85. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, Laura. 2002. Understanding completion entailments in the absence of agency cues. Journal of Child Language 29: 109–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Wagner, Laura. 2012. First language acquisition. In The Oxford Handbook of Tense and Aspect. Edited by Robert Binnick. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 458–80. [Google Scholar]

- Weist, Richard, Hanna Wysocka, and Paula Lyytinen. 1991. A cross-linguistic perspective on the development of temporal systems. Journal of Child Language 18: 67–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weist, Richard, Paula Lyytinen, Jolanta Wysocka, and Miroslava Atanassova. 1997. The interaction of language and thought in children’s language acquisition: A crosslinguistic study. Journal of Child Language 24: 81–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winskel, Heather. 2004. The acquisition of temporal reference cross-linguistically using two acting-out comprehension tasks. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 33: 333–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wubs, Ellen, Petra Hendriks, John Hoeks, and Charlotte Koster. 2009. Tell me a story! Children’s capacity for topic shift. In Proceedings of the 3rd Conference on Generative Approaches to Language Acquisition North America (GALANA 2008). Edited by Jean Crawford, Koichi Otaki and Masahiki Takahashi. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 313–24. [Google Scholar]

| Setting | PI > IMP | IMP > PI |

|---|---|---|

| Narrative | 5 children *; 4 adults | 6 children; 4 adults |

| Non-narrative | 6 children; 4 adults | 6 children; 5 adults |

| Picture Pair | PI | IMP |

|---|---|---|

| Complete-Ongoing (C–O) | Complete | Ongoing |

| Complete-Incomplete (C–I) | Complete | None |

| Ongoing-Incomplete (O–I) | None | Ongoing |

| Narrative | Non-Narrative | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Adults | PI | 8.00 | 0.756 | 6.44 | 1.810 |

| IMP | 8.50 | 0.535 | 8.44 | 1.014 | |

| Children | PI | 5.67 | 1.414 | 4.31 | 1.653 |

| IMP | 3.44 | 1.130 | 5.08 | 1.038 | |

| Model 1 Exp (coef) | Model 2 Exp (coef) | |

|---|---|---|

| Referential profile (intercept) | 4.08 *** (1) | 169.49 *** (2) |

| Age Children | 0.06 *** | 0.34 |

| Aspect IMP | 9.17 *** | 0.61 |

| Situation Non-narrative | 0.32 ** | 0.32 ** |

| Picture-pair C–O O–I | 2.98 *** 22.33 *** | -- |

| Target-answer Complete None | -- | 0.06 * 0.04 *** |

| Age x situation | 2.69 ** | 2.65 * |

| Aspect x picture pair C–O O–I | 0.49 0.00 *** | -- |

| Age x aspect | -- | 0.14 ** |

| Age x target-answer Complete None | -- | 0.47 0.21 (3) |

| Situation | Picture Choice | Adults | Children |

|---|---|---|---|

| Narrative | Ongoing | 24 | 13 |

| Complete | 0 | 17 | |

| None | 0 | 3 | |

| Non-narrative | Ongoing | 26 | 32 |

| Complete | 0 | 3 | |

| None | 1 | 1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García-del-Real, I.; van Hout, A. Interpretation of Imperfective Past Tense in Spanish: How Do Child and Adult Language Varieties Differ? Languages 2022, 7, 237. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7030237

García-del-Real I, van Hout A. Interpretation of Imperfective Past Tense in Spanish: How Do Child and Adult Language Varieties Differ? Languages. 2022; 7(3):237. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7030237

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía-del-Real, Isabel, and Angeliek van Hout. 2022. "Interpretation of Imperfective Past Tense in Spanish: How Do Child and Adult Language Varieties Differ?" Languages 7, no. 3: 237. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7030237

APA StyleGarcía-del-Real, I., & van Hout, A. (2022). Interpretation of Imperfective Past Tense in Spanish: How Do Child and Adult Language Varieties Differ? Languages, 7(3), 237. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7030237