How Effective Are the Different Family Policies for Heritage Language Maintenance and Transmission in Australia?

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Home Language Policy: Type of Approach and Maintenance Level

1.2. Practical Difficulty in Defining Home Language Policy

1.3. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

Participants

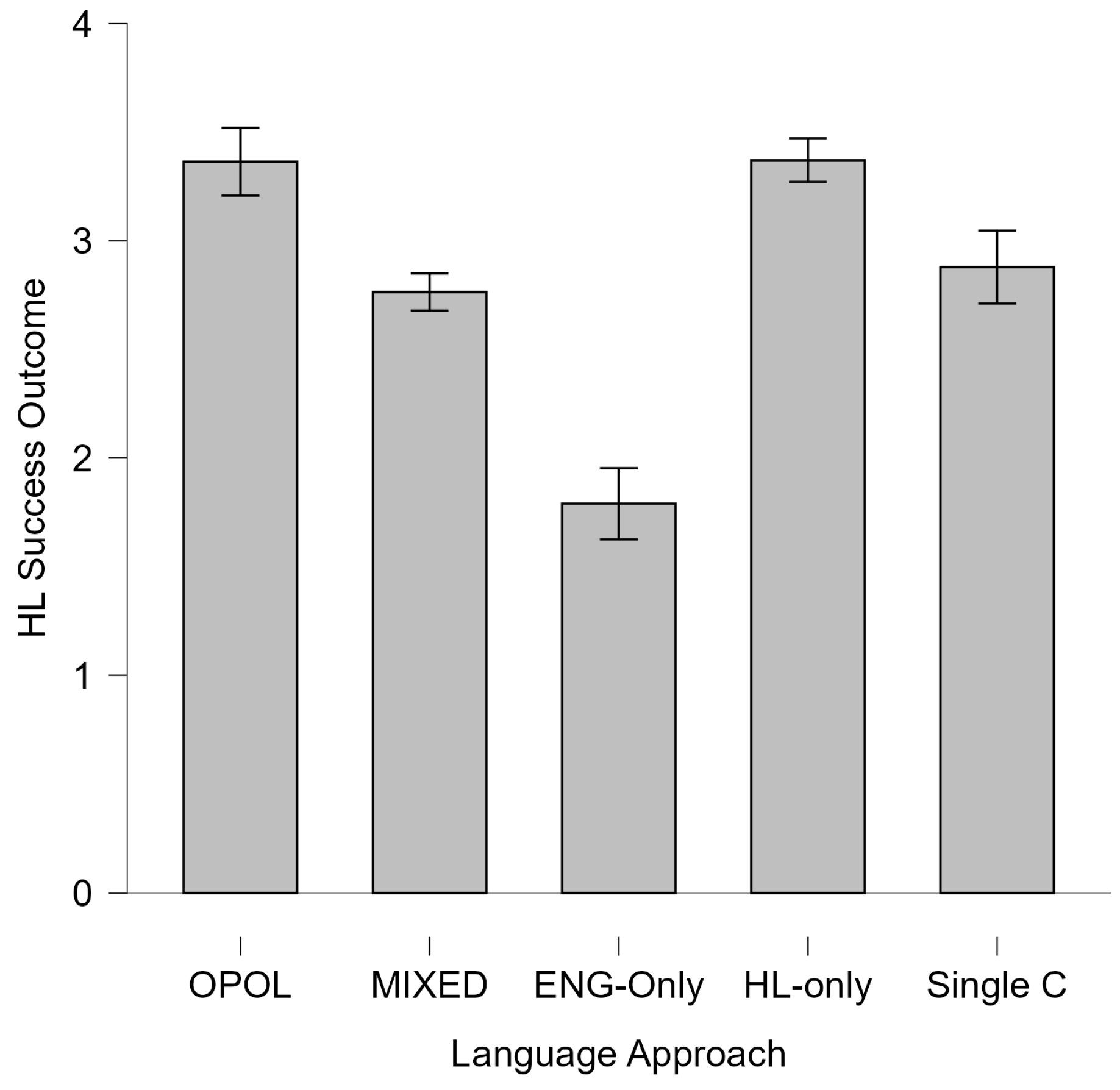

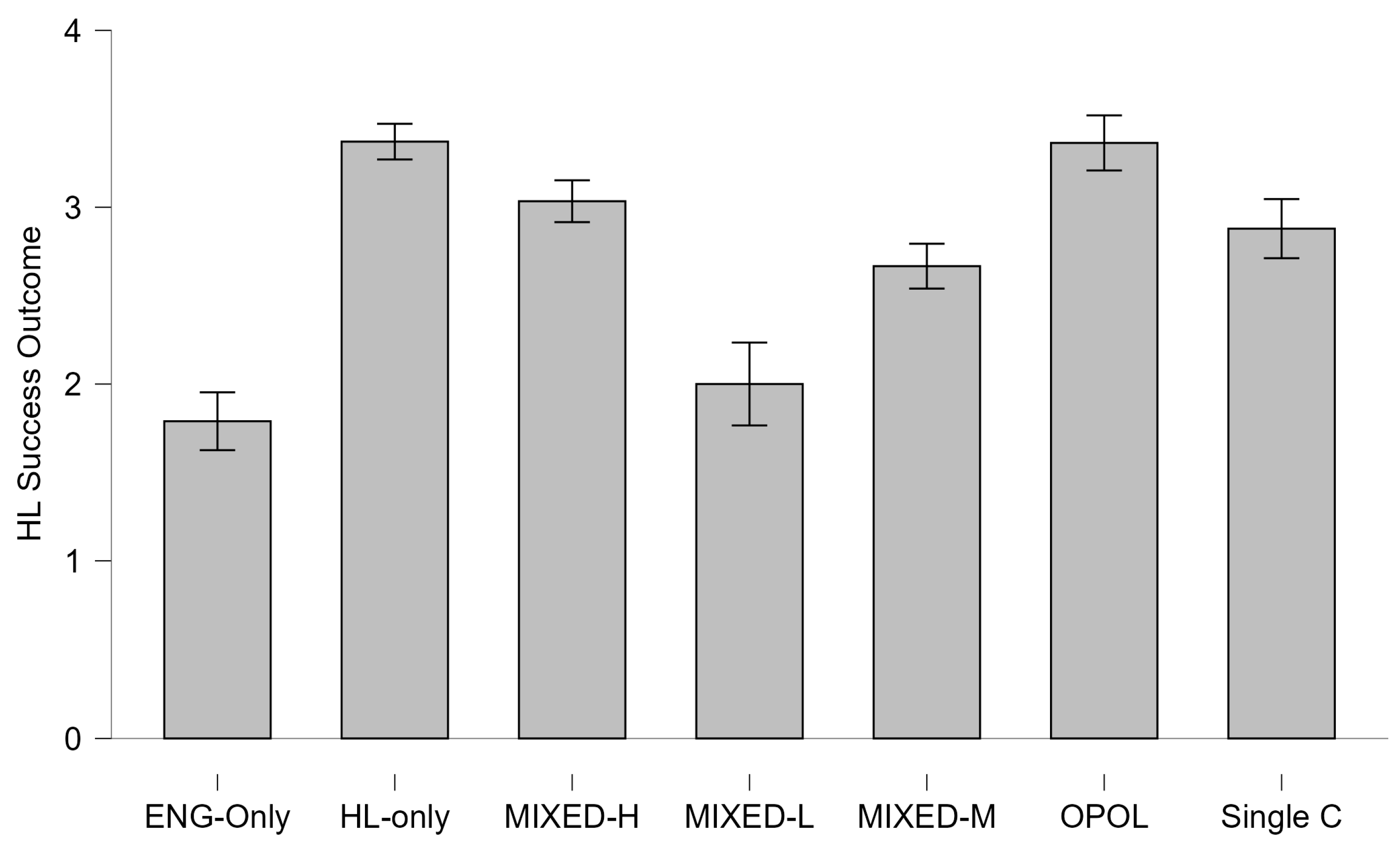

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Questions Used for Analyses | If Respondent Was the Primary Caregiver | If Respondent Was the Secondary Caregiver |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Caregiver role | Are you their primary caregiver? ☐ Yes—I am the primary caregiver ☐ No—I am the secondary caregiver | Are you their primary caregiver? ☐ Yes—I am the primary caregiver ☐ No—I am the secondary caregiver |

| 2. Relationship to children | ☐ Mother ☐ Father ☐ Grandmother ☐ Grandfather ☐ Foster carer ☐ Other—please specify ___________ | ☐ Mother ☐ Father ☐ Grandmother ☐ Grandfather ☐ Foster carer ☐ Other—please specify ___________ |

| 3. Time spent with children on a regular day, averaged over the week | ☐ 0% ☐ 25% ☐ 50% ☐ 75% ☐ 100% | ☐ 0% ☐ 25% ☐ 50% ☐ 75% ☐ 100% |

| 4. Languages spoken with children | (Dropdown of respondent’s previously selected language(s) to select) | (Dropdown of respondent’s previously selected language(s) to select) |

| 5. Percentage of time speaking each language to children; the total should not exceed 100 percent | (Dropdown with language(s) chosen in previous question and percentage section to fill in) | (Dropdown with language(s) chosen in previous question and percentage section to fill in) |

| 6. Presence of another caregiver | Do your children have a secondary caregiver? ☐ Yes ☐ No | ---Not applicable--- |

| 7. Relationship of other caregiver to children | How is your children’s secondary caregiver related to them? ☐ Mother ☐ Father ☐ Grandmother ☐ Grandfather ☐ Foster carer ☐ Other—please specify ___________ | How is your children’s primary caregiver related to them? ☐ Mother ☐ Father ☐ Grandmother ☐ Grandfather ☐ Foster carer ☐ Other—please specify ___________ |

| 8. Time the other caregiver spends with children on a regular day, averaged over the week | ☐ 0% ☐ 25% ☐ 50% ☐ 75% ☐ 100% | ☐ 0% ☐ 25% ☐ 50% ☐ 75% ☐ 100% |

| 9. Languages spoken by other caregiver with children | (Dropdown of previously indicated languages for secondary caregiver) | (Dropdown of previously indicated languages for primary caregiver) |

| 10. Percentage of time other caregiver speaks these languages to children; the total should not exceed 100 percent | (Dropdown with language(s) chosen in previous question and percentage section to fill in) | (Dropdown with language(s) chosen in previous question and percentage section to fill in) |

| 11. Perceived success in raising children multilingually | How would you rate your success in transferring and maintaining your home languages and raising your children multilingually? | How would you rate your success in transferring and maintaining your home languages and raising your children multilingually? |

References

- ABS—Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2022). Cultural diversity of Australia. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/cultural-diversity-australia (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Barron-Hauwaert, S. (2004). Language strategies for bilingual families: The one-parent-one-language approach. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Cangelosi, M., Borghetti, C., & Bonifacci, P. (2024). How parents’ perceived value of the heritage language predicts their children’s skills. Languages, 9(3), 80. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2226-471X/9/3/80 (accessed on 15 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Cho, G., Cho, K. S., & Tse, L. (1997). Why ethnic minorities want to develop their heritage language: The case of Korean-Americans. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 10(2), 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clyne, M. (2004). Empowerment through the community language—Does it work? In Empowerment through language (p. 22). Linguistic Agency. [Google Scholar]

- Curdt-Christiansen, X. L., & Palviainen, Å. (2023). Ten years later: What has become of FLP? Language Policy, 22(4), 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Houwer, A. (2007). Parental language input patterns and children’s bilingual use. Applied Psycholinguistics, 28(3), 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Houwer, A. (2011). Language input environments and language development in bilingual acquisition. Applied Linguistics Review, 2(2), 221–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Houwer, A. (2017). Bilingual language input environments, intake, maturity and practice. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 20(1), 19–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Houwer, A. (2020). 4 Harmonious Bilingualism: Well-being for families in bilingual settings. In Handbook of home language maintenance and development (pp. 63–83). De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diskin-Holdaway, C., & Escudero, P. (under review). Parental language attitudes towards their children’s accent: Findings from a nationwide survey in Australia. Languages. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenchlas, S. A., & Schalley, A. C. (2017). Reaching out to migrant and refugee communities to support home language maintenance. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escudero, P., Diskin-Holdaway, C., Pino Escobar, G., & Hajek, J. (2025a). Needs and demands for heritage language support in Australia: Results from a nationwide survey. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 46, 437–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escudero, P., Pino Escobar, G., Diskin-Holdaway, C., & Hajek, J. (2025b). Enhancing heritage and additional language learning in the preschool years: Longitudinal implementation of the Little Multilingual Minds program. Frontiers in Language Sciences, 4, 1604196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escudero, P., Pino Escobar, G., Tran, M. A., Tran, M. L., & Hajek, J. (under review a). Addressing the needs and demands of heritage language and additional language preschool learners: An evaluation of a Vietnamese immersion program in Australia.

- Escudero, P., Tran, M. A., Pino Escobar, G., & Diskin-Holdaway, C. (under review b). Parental attitudes toward Vietnamese language learning for heritage and non-heritage preschool children in Australia. Languages. [Google Scholar]

- Fishman, J. A. (1991). Reversing language shift: Theoretical and empirical foundations of assistance to threatened languages (Vol. 76). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Grasso, S. (2024). Navigating language maintenance challenges with health professionals: Reflections from Spanish speaking families in Australia. Australian Journal of Linguistics, 44(1), 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, A. W. (2010). The heart of heritage: Sociocultural dimensions of heritage language learning. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 30, 66–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoff, E., & Core, C. (2013). Input and language development in bilingually developing children. Seminars in Speech and Language, 34(4), 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humeau, C., Guimard, P., Nocus, I., & Galharret, J.-M. (2025). Parental language practices and children’s use of the minority language: The mediating role of children’s language attitudes. International Journal of Bilingualism, 29(1), 40–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JASP Team. (2024). JASP (Version 0.19.0) [Computer software]. Available online: https://jasp-stats.org/info/ (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Karidakis, M., & Arunachalam, D. (2016). Shift in the use of migrant community languages in Australia. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 37(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. H. O., & Starks, D. (2010). The role of fathers in language maintenance and language attrition: The case of Korean–English late bilinguals in New Zealand. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 13(3), 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, K. A., Fogle, L., & Logan-Terry, A. (2008). Family language policy. Language and Linguistics Compass, 2(5), 907–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelewijn, I. M., Hoevenaars, E., & Verhagen, J. (2023). How do parents think about multilingual upbringing? Comparing OPOL parents and parents who mix languages. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 46, 765–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanza, E. (2007). 2. Multilingualism and the family. In A. Peter, & W. Li (Eds.), Handbook of multilingualism and multilingual communication (pp. 45–68). De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanza, E., & Gomes, R. L. (2020). Family language policy: Foundations, theoretical perspectives and critical approaches. In Handbook of home language maintenance and development: Social and affective factors (Vol. 18, pp. 153–173). Walter de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Liddicoat, A. J. (2017). Indigenous and immigrant languages in Australia. In Heritage language policies around the world (pp. 237–253). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Montrul, S., & Silva-Corvalán, C. (2019). The social context contributes to the incomplete acquisition of aspects of heritage languages. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 41(2), 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauwels, A. (2005). Maintaining the community language in Australia: Challenges and roles for families. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 8(2–3), 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauwels, A. (2016). Language maintenance and shift. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, B. Z. (2008). Raising a bilingual child. Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Piller, I., Butorac, D., Farrell, E., Lising, L., Motaghi-Tabari, S., & Williams Tetteh, V. (2024). Life in a new language. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanowski, P. (2021). A deliberate language policy or a perceived lack of agency: Heritage language maintenance in the Polish community in Melbourne. International Journal of Bilingualism, 25(5), 1214–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanowski, P. (2022). Paternal agency in heritage language maintenance in Australia: Polish fathers in action. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 25(9), 3320–3332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawir, E. (2005). Language difficulties of international students in Australia: The effects of prior learning experience. International Education Journal, 6(5), 567–580. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ855010.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Schalley, A. C., & Eisenchlas, S. A. (2022). Parental Input in the Development of children’s multilingualism. In A. Stavans, & U. Jessner (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of childhood multilingualism (pp. 278–303). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, M., & Verschik, A. (2013). Achieving success in family language policy: Parents, children and educators in interaction. In Successful family language policy: Parents, children and educators in interaction (pp. 1–20). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, C., & Jiang, W. (2023). Parents’ planning, children’s agency and heritage language education: Re-storying the language experiences of three Chinese immigrant families in Australia. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spolsky, B. (2012). Family language policy—The critical domain. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 33(1), 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F., & Calafato, R. (2024). “You have to repeat Chinese to mother!”: Multilingual identity, emotions, and family language policy in transnational multilingual families. Applied Linguistics Review, 15(2), 427–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F., & Calafato, R. (2025). Family language policy: The impact of multilingual experiences at university and language practices at home. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 28(1), 92–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannenbaum, M., & Berkovich, M. (2005). Family relations and language maintenance: Implications for language educational policies. Language Policy, 4(3), 287–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannenbaum, M., & Howie, P. (2002). The association between language maintenance and family relations: Chinese immigrant children in Australia. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 23(5), 408–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torsh, H. I. (2022). ‘Maybe if you talk to her about it’: Intensive mothering expectations and heritage language maintenance. Multilingua, 41(5), 611–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torsh, H. I., & Lising, L. (2022). Multilingual family language policy in monolingual Australia: Multilingual desires and monolingual realities. Multilingua, 41(5), 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venables, E., Eisenchlas, S. A., & Schalley, A. C. (2014). One-parent-one-language (OPOL) families: Is the majority language-speaking parent instrumental in the minority language development? International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 17(4), 429–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhagen, J., Kuiken, F., & Andringa, S. (2022). Family language patterns in bilingual families and relationships with children’s language outcomes. Applied Psycholinguistics, 43(5), 1109–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J. A., Hajek, J., Loakes, D., Diskin-Holdaway, C., & Docherty, G. (2024). The sociolinguistics of urban multilingualism. In Multifaceted multilingualism (Vol. 66, p. 395). John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H., & Hatoss, A. (2024). Language policy and planning for heritage language maintenance: A scoping review. Current Issues in Language Planning, 25(5), 612–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Williams Tetteh, V., & Dube, S. (2023). Parental emotionality and power relations in heritage language maintenance: Experiences of Chinese and African immigrant families in Australia. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1076418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Primary Carer | n | % | Secondary Carer | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mother | 247 | 88.21 | Father | 198 | 70.71 |

| Father | 32 | 11.43 | Mother | 25 | 8.93 |

| Other | 1 | 0.36 | Other | 20 | 7.14 |

| No-SC | 37 | 13.21 | |||

| Total | 280 | 100.00 | Total | 280 | 100.00 |

| Relationship with Children (n) | % Time Spent with Children M (SD) | % Time Speaking HL to Children M (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PC | Mother (n = 216) | 0.63 (0.24) | 0.66 (0.37) |

| Father (n = 27) | 0.43 (0.18) | 0.60 (0.41) | |

| Single Carer (n = 37) | 0.57 (0.29) | 0.59 (0.38) | |

| SC | Mother (n = 25) | 0.48 (0.20) | 0.58 (0.43) |

| Father (n = 198) | 0.43 (0.20) | 0.46 (0.44) | |

| Other (n = 20) | 0.44 (0.26) | 0.51 (0.48) |

| OPOL n = 33 | ENG-Only n = 19 | No-SC n = 33 | MIXED n = 133 | HL-Only n = 62 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC | SC | PC | SC | PC | SC | PC | SC | PC | SC | |

| Mean | 0.96 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.66 | - | 0.54 | 0.38 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| SD | 0.17 | 0.31 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.34 | 0.31 | 0.36 | 0.01 | 0.00 | |

| Min | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.95 | 1.00 | |

| Max | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Success Level | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| 4 Very successful | 103 | 36.79 |

| 3 Moderately successful | 79 | 28.21 |

| 2 Somewhat successful | 74 | 26.43 |

| 1 Not successful | 24 | 8.57 |

| Total | 280 | 100 |

| Comparison | z | Wi | Wj | rrb | p | pbonf |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPOL–MIXED | 3.26 | 173.08 | 124.91 | 0.36 | 0.001 | 0.011 |

| OPOL–ENG-only | 5.42 | 173.08 | 55.05 | 0.79 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| OPOL–HL-only | 0.06 | 173.08 | 172.07 | 0.02 | 0.951 | 1 |

| OPOL–No-SC | 2.16 | 173.08 | 132.89 | 0.29 | 0.031 | 0.308 |

| MIXED–ENG-only | 3.76 | 124.91 | 55.05 | 0.55 | <0.001 | 0.002 |

| MIXED–HL-only | −4.03 | 124.91 | 172.07 | 0.35 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| MIXED–No-SC | −0.54 | 124.91 | 132.89 | 0.05 | 0.589 | 1 |

| ENG-only–HL-only | −5.90 | 55.05 | 172.07 | 0.81 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| ENG-only–No-SC | −3.58 | 55.05 | 132.89 | 0.59 | <0.001 | 0.003 |

| HL-only–No-SC | 2.41 | 172.07 | 132.89 | 0.29 | 0.016 | 0.162 |

| MIXED-H | MIXED-M | MIXED-L | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 59 | n = 54 | n = 14 | ||||

| PC | SC | PC | SC | PC | SC | |

| Mean | 0.75 | 0.56 | 0.38 | 0.27 | 0.10 | 0.05 |

| SD | 0.23 | 0.40 | 0.19 | 0.25 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Min | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.01 | 0 |

| Max | 1 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.2 | 0.13 |

| Comparison | z | Wi | Wj | rrb | p | pbonf |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ENG-Only–HL-only | −5.90 | 55.05 | 172.07 | 0.81 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| ENG-Only–MIXED-H | −4.53 | 55.05 | 145.28 | 0.68 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| ENG-Only–OPOL | −5.42 | 55.05 | 173.08 | 0.79 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| ENG-Only–No-SC | −3.58 | 55.05 | 132.89 | 0.59 | <0.001 | 0.007 |

| ENG-Only–MIXED-M | −3.07 | 55.05 | 116.98 | 0.51 | 0.002 | 0.045 |

| ENG-Only–MIXED-L | −0.55 | 55.05 | 69.64 | 0.12 | 0.584 | 1 |

| MIXED-L–MIXED-M | −2.09 | 69.64 | 116.98 | 0.40 | 0.037 | 0.773 |

| MIXED-L–OPOL | −4.29 | 69.64 | 173.08 | 0.69 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| MIXED-L–No-SC | −2.62 | 69.64 | 132.89 | 0.48 | 0.009 | 0.183 |

| MIXED-M–OPOL | −3.36 | 116.98 | 173.08 | 0.42 | <0.001 | 0.016 |

| MIXED-M–No-SC | −0.95 | 116.98 | 132.89 | 0.11 | 0.341 | 1 |

| MIXED-H–MIXED-L | 3.37 | 145.28 | 69.64 | 0.57 | <0.001 | 0.016 |

| MIXED-H–MIXED-M | 1.99 | 145.28 | 116.98 | 0.22 | 0.047 | 0.984 |

| MIXED-H–OPOL | −1.69 | 145.28 | 173.08 | 0.22 | 0.091 | 1 |

| MIXED-H–No-SC | 0.75 | 145.28 | 132.89 | 0.10 | 0.451 | 1 |

| HL-only–OPOL | −0.06 | 172.07 | 173.08 | 0.02 | 0.951 | 1 |

| HL-only–MIXED-H | 1.95 | 172.07 | 145.28 | 0.21 | 0.051 | 1 |

| HL-only–MIXED-M | 3.92 | 172.07 | 116.98 | 0.42 | <0.001 | 0.002 |

| HL-only–MIXED-L | 4.58 | 172.07 | 69.64 | 0.72 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| HL-only–No-SC | 2.41 | 172.07 | 132.89 | 0.29 | 0.016 | 0.34 |

| OPOL–No-SC | 2.16 | 173.08 | 132.89 | 0.29 | 0.031 | 0.648 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pino Escobar, G.; Diskin-Holdaway, C.; Escudero, P. How Effective Are the Different Family Policies for Heritage Language Maintenance and Transmission in Australia? Languages 2025, 10, 290. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10120290

Pino Escobar G, Diskin-Holdaway C, Escudero P. How Effective Are the Different Family Policies for Heritage Language Maintenance and Transmission in Australia? Languages. 2025; 10(12):290. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10120290

Chicago/Turabian StylePino Escobar, Gloria, Chloé Diskin-Holdaway, and Paola Escudero. 2025. "How Effective Are the Different Family Policies for Heritage Language Maintenance and Transmission in Australia?" Languages 10, no. 12: 290. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10120290

APA StylePino Escobar, G., Diskin-Holdaway, C., & Escudero, P. (2025). How Effective Are the Different Family Policies for Heritage Language Maintenance and Transmission in Australia? Languages, 10(12), 290. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10120290