Traditionally, agreement patterns in English (and other modern Germanic languages) are discussed in terms of there being two numbers, singular and plural, three genders, masculine, feminine and neuter, and three persons, first, second and third, and agreement (or concord) patterns are defined in terms of these categories. However, as briefly discussed at the end of the introductory section, these categories have limited, if any, usefulness in the grammatical system of English, given the very restricted agreement patterns displayed. In order to account for gender and number agreement between anaphoric and reflexive pronouns and their antecedents, the collocational constraints on determiner plus noun combinations and the vestigial subject–verb agreement, I do not mimic such grammatical categories directly and propose instead to reference the forms of agreeing words to capture the allowable collocations. To this end, I introduce a new label (for ‘morphological dependency’) which takes as values sets of phonological forms, i.e., sets of ordered sets of phonemes. As will become evident during the discussion, the set of forms that need to be set up to act as values to the label is not only finite but very small and restricted to closed-class expressions such as pronouns and determiners. I begin by analysing anaphoric agreement, and then move on to determiner–noun concord and finally to subject–verb agreement.

3.1. Anaphora

I start my analysis by reviewing the theory of third person anaphora introduced in

Kempson et al. (

2001), which skirts around the problem of matching gendered pronouns with appropriate antecedents, merely subscripting metavariables with labels like

masc, fem, pl, etc. without addressing what these subscripts are actually mean. Such matching is, of course, profoundly important in understanding (and producing) utterances as illustrated in the short dialogue in (13):

| (13) | A: Mike gave Jean some daffodils. |

| B: Did he? Did she like them? |

For anyone like me, for whom

Mike is a name for males and

Jean for females, the most accessible antecedents are

Mike for

he,

Jean for

she and

the daffodils for

them, but the rule of

Substitution introduced in

Kempson et al. (

2001), which selects some type-matched formula in context and substitutes that for a metavariable projected by an anaphor, cannot ensure this and allows any of the potential antecedents to be associated with any of the pronouns in (13). A proper analysis of what it is that determines the correct dependencies needs a sound theoretical basis within the tenets of DS.

A potential solution is to treat the subscripts on metavariables as semantic in nature, so that a metavariable like entails (or presupposes) that any substituent must have a plural meaning. Of course, this fails immediately because grammatical number is not isomorphic with the mental concepts that it can express. While the plural markers in English often indicate that some concept is to be taken as a real plurality, this may not be the case, and the denotata may be singular such as with trousers, scissors, etc. Such expressions nevertheless require a pronominal anaphor to be plural they not singular it. Conversely, the fact that an expression is not morphologically plural only weakly implicates that what it denotes does not consist of discrete parts, as with nouns like committee and furniture.

Similarly, it cannot be taken for granted that she or he necessarily always refers to female or male entities. So dog may be referred to with any of the third singular pronouns, bull with he or it, ship with she or it and so on. And in our flexibly gendered times, the pronoun that might be used for the biological gender of a human baby may not, in fact, be applicable, either through choice or biology.

To account for these facts, I take up and develop an idea proposed in

Cann (

2000) where it is suggested that there is a significant cognitive distinction between ‘lexical’ and ‘functional’ categories: the former are defined intensionally in terms of overarching syntactic categories or semantic types and the latter simply in terms of sets of word forms. While I do not accept the hypothesis that there is a real cognitive dichotomy involved, nevertheless I here adopt the proposal that certain, closed-class expressions, individually or in sets, per se, may play an important part in the grammars of natural languages, independently of any syntactic or semantic categorisation. It is the phonological forms of these expressions that I take to define the possible values for the

label mentioned above. This label encodes the set of expressions with which another expression or set of expressions such as nouns and verbs can be linked to, or collocated with. While being a purely morpho-syntactic label, not ultimately grounded in meaning,

is nevertheless grounded in the objective obverse of meaning, phonology and ultimately in phonetics realised as sound waves.

Dependent forms, such as anaphoric pronouns, are sensitive to particular values of an

label. Hence, I treat nouns as associated with the set of phonological representations of the various forms of the personal pronouns that are associated with them as possible co-referring expressions. So we have labels such as

h,i

h,ɪ,m

h,ɪ,z

or

ʃ,i

h,ə,r

or even

h,i

h,ɪ,m

h,ɪ,z

ʃ,i

h,ə,r

ɪ,t

ɪ,t,s

. The parse of a common noun I thus take as involving not just projecting type, formula and phonological labels but also an

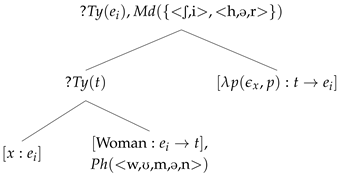

label which decorates the dominating term node. As an example, (14) shows the lexical entry for

woman and (15) the tree that results in parsing

a woman:

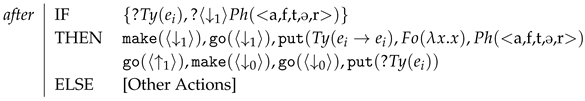

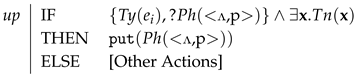

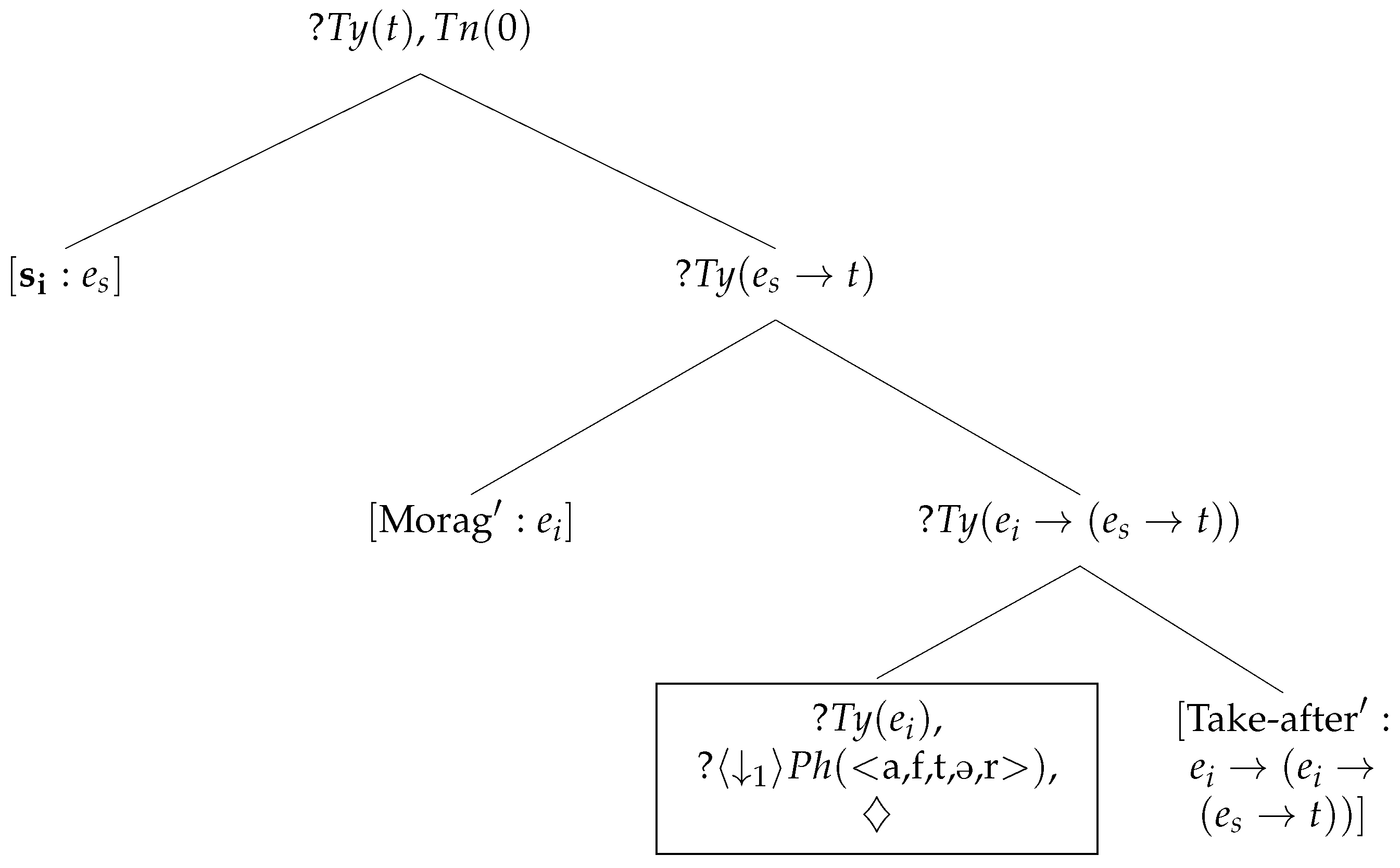

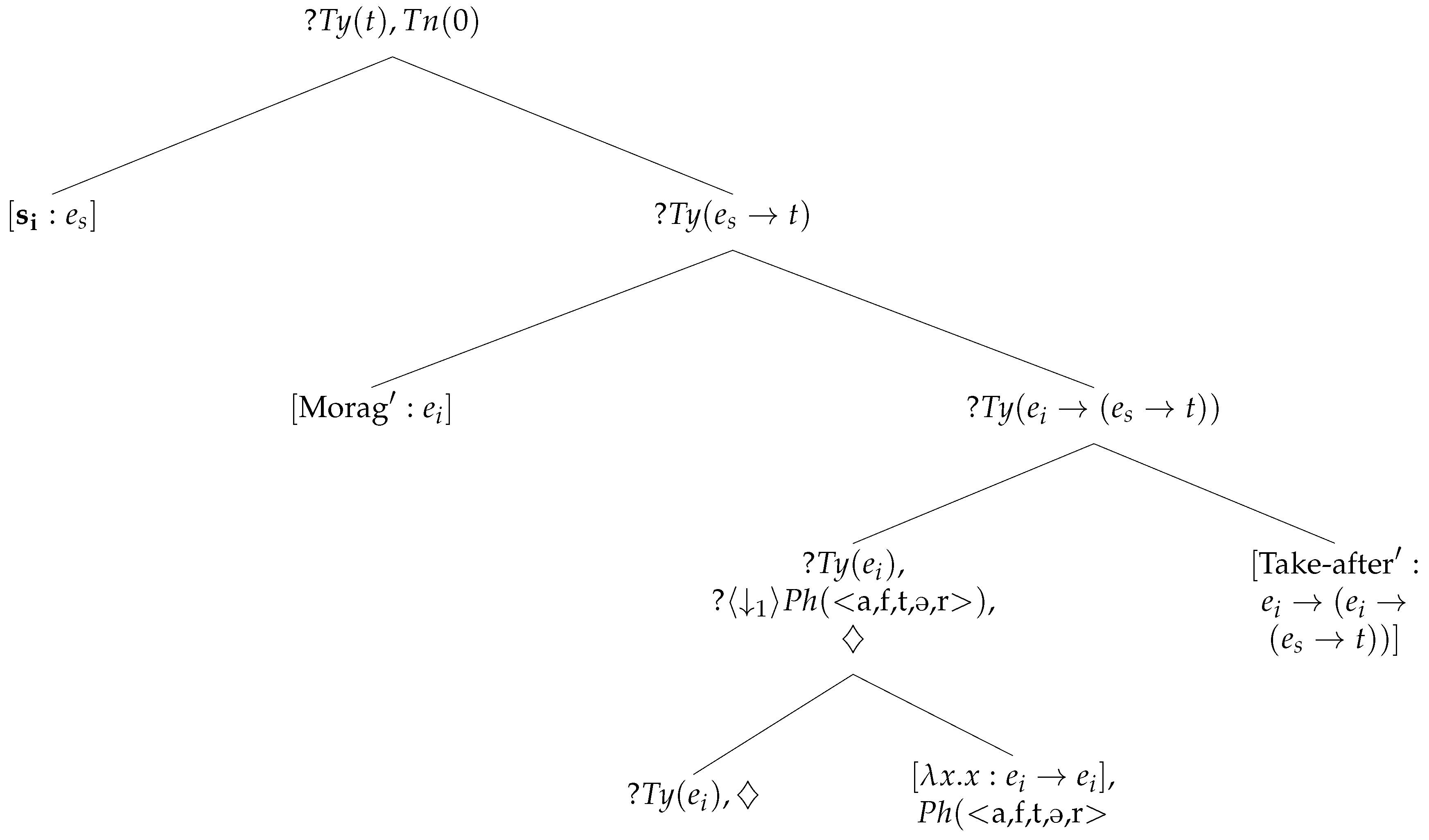

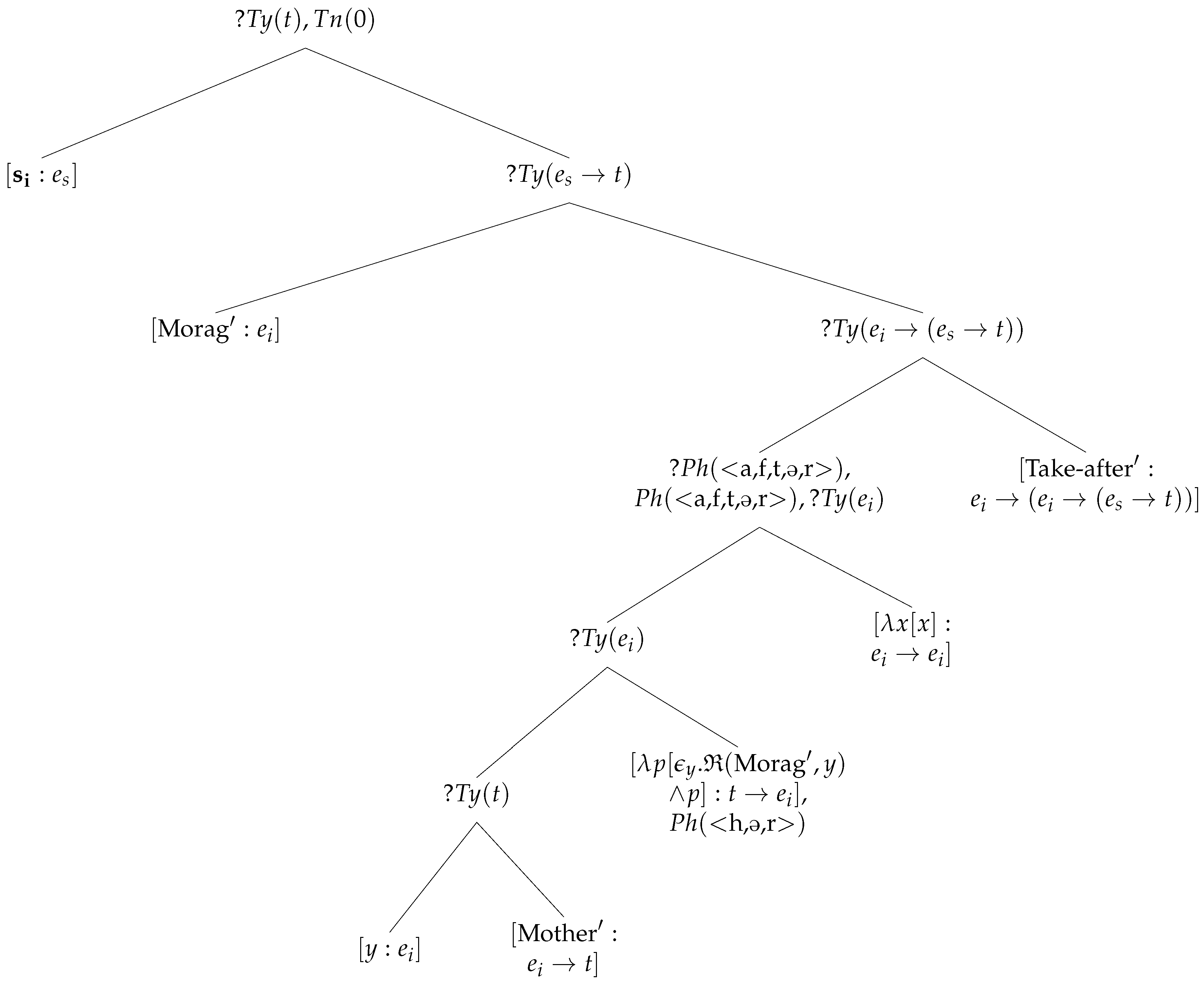

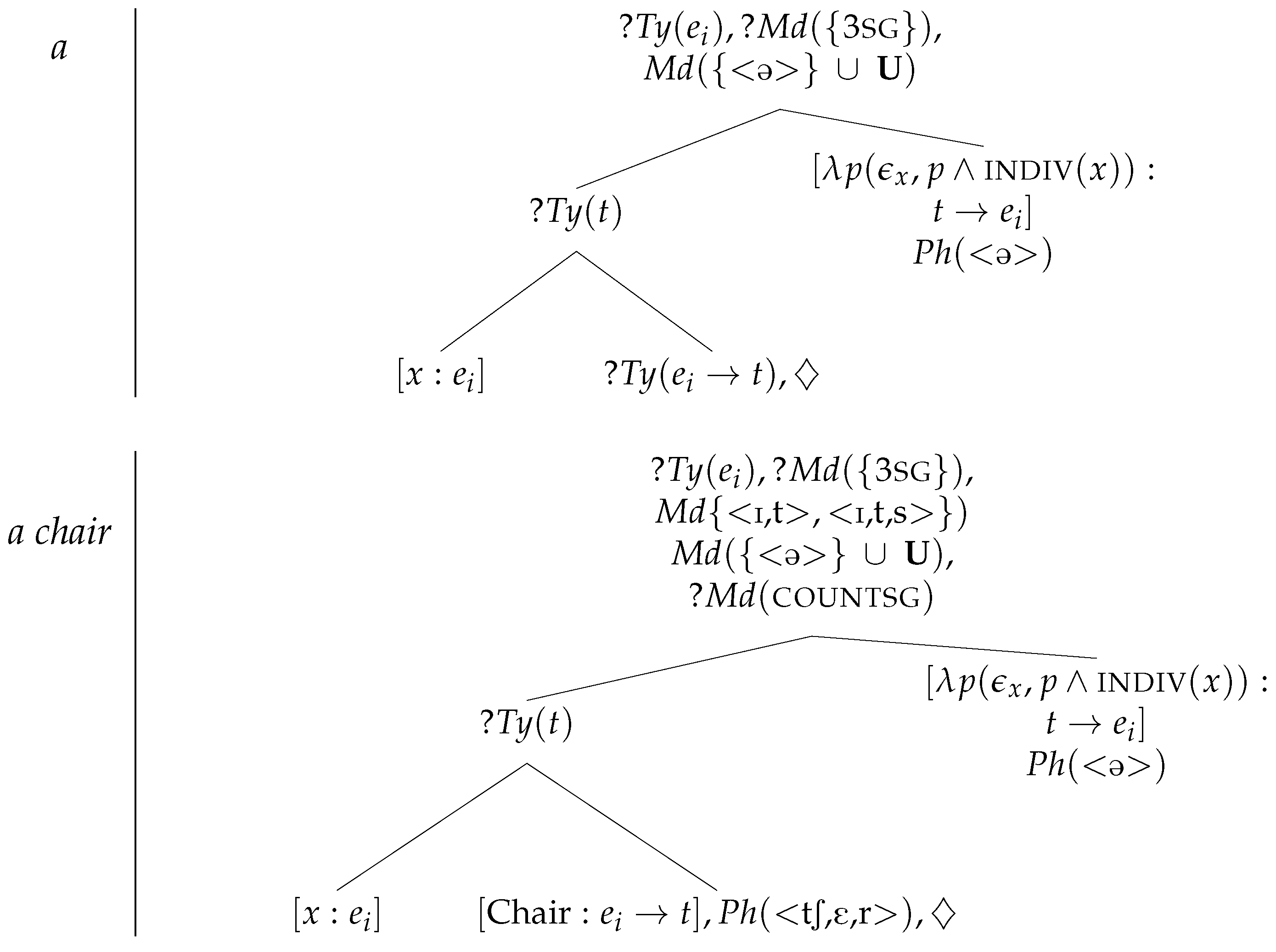

9| (14) | ![Languages 10 00289 i003 Languages 10 00289 i003]() |

| (15) | Parsing a woman: | ![Languages 10 00289 i004 Languages 10 00289 i004]() |

Pronouns are also associated with

values so that

she, her like

woman and other feminine nouns project

ʃ,i

h,ə,r

in addition to a metavariable and associated formula requirement. The process of

Substitution assumed in

Kempson et al. (

2001),

Cann et al. (

2005) and many others replaces a metavariable with some other type-matching formula from the current context.

10 To ensure a proper match between antecedents and pronouns, this process needs also to be made sensitive to the

values of both anaphor and antecedent. Hence, the rule targets a tree

in a context

that contains a node with a formula value not only of a matching type but also a matching

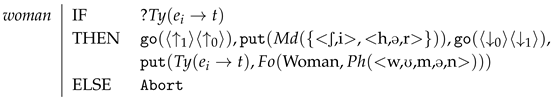

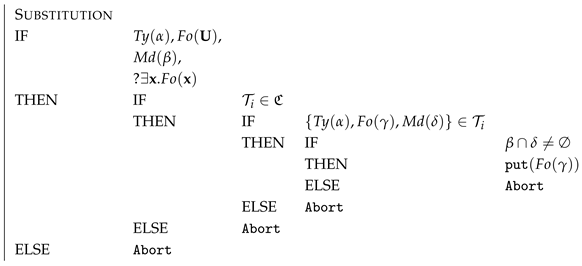

value. The relevant actions are given in (16):

11,12| (16) | ![Languages 10 00289 i005 Languages 10 00289 i005]() |

Notice that the relation between the values is one of non-empty intersection, not identity. This is because words like dog, bull, and ship mentioned above carry an value that covers more than one set of potential anaphoric forms. So cow projects ʃ,ih,ə,rɪ,tɪ,t,s, which needs to match both feminine (ʃ,ih,ə,r) and neuter (ɪ,tɪ,t,s) pronouns. The rule of Substitution in (16) ensures that the pronouns in (13) are paired with the appropriate antecedents under the following assumptions: the referent of Mike is, for the speaker, male, and so the word is associated with h,ih,ɪ,mh,ɪ,z as is the pronoun he; the speaker’s intended referent for Jean is female and so associated with ʃ,ih,ə,r as is she; and plural noun phrases like the daffodils and forms of the third person plural pronoun are associated with ð,ɛ,ið,ɛ,mð,ɛ,r. Given that the requirement for values on anaphors and antecedents have a non-null intersection, no other construal is possible.

The same sort of analysis for agreement with pronominal anaphors and antecedents can be used for reflexives. The third person reflexive pronouns

himself, herself, itself, and

themselves all require agreement with their local antecedent (where, as usual in DS, ‘local’ signifies the minimal propositional domain containing some node):

| (17) | a. | Mary doesn’t like herself/*itself/*himself/*themselves very much at the moment. |

| b. | I told that man to get himself/*herself/*itself/*themselves together. |

| c. | Someone sent me the students’ pictures of themselves/*himself/*herself/*itself. |

As in

Kempson et al. (

2001) and

Cann et al. (

2005), I adopt an analysis which provides lexical actions for the reflexive pronouns that mimic a local version of

Substitution which excludes the possibility of there being a discourse or non-local antecedent. However, no metavariable is projected by these actions, so no actual substitution is involved. So

herself unlike

she, her is restricted to local (proposition internal) antecedents with an

value

ʃ,i

h,ə,r

as shown in the lexical actions in (18):

| (18) | herself | | | |

| IF | | | |

| THEN | | | |

| ʃ,ih,ə,r | | |

| | | |

| | | |

| IF | | |

| THEN | IF | ʃ,ih,ə,r |

| | THEN | |

| | | |

| | ELSE | Abort |

| ELSE | Abort | |

| ELSE | Abort | | |

The actions thus add the appropriate type and

labels to the trigger node, target the closest propositional node, seek a locally dominated node of type

decorated with a formula value

and an

value that has a non-null intersection with the feminine value and then return the pointer to the original node and copy the formula

. So for the datum in (17a), the grammatical version yields the desired output:

.

Another thing to note about the theory of agreement presented in this paper is that it is not fully deterministic. If it were, then it should be impossible to resolve the antecedent for the pronoun

they/them in examples like those in (19):

| (19) | a. | Every dog adores whoever feeds it. They are such fickle creatures. |

| b. | No student came to the tutorial. None of them had done the set work. |

The reason that it should be impossible to resolve

they to

every dog or

them to

no student is that the

values do not share at least one value, so that singular referents should not be compatible with plural anaphors. What, of course, is happening here is that the plural third person pronoun, while not entailing plurality, implicates it, and this implicature induces pragmatic enrichment of the formula of the antecedent to yield an appropriate group referent for the pronoun. Thus, in (19a), the substitution of the antecedent formula for the metavariable projected by the anaphor does not pick up the quantificational force of the antecedent but refers to some contextually maximal group of dogs (in this case the kind), while in (19b), it identifies the maximal group of students who are in the tutorial group. Hence,

Substitution that involves matching

values can be overridden just in case any implicature of the anaphor can be used to create an appropriate referent based on the semantic properties of the putative antecedent and, in particular, the head noun that incorporates the content of the relevant implicature.

The same sort of semantic/pragmatic agreement occurs with respect to the third person plural pronouns whose antecedents are conjoined singular NPs as with

Malcolm and John hugged each other. They were lovers once. While easy enough to explain under the assumption that the NP

Malcolm and John denotes a group (however defined) and

they implicates a group antecedent, as with the examples in (19), the implicature allows the anaphoric link between the pronoun and the conjoined NP, as desired. There is, however, a problem. Consider, for example,

Gordon and Sarah said they were not going to the USA this year. The analysis of co-ordinate structures in DS involves a

link relation between two type-identical nodes, here

, where

linked trees relate to, but are independent of, the parse tree under construction (

Cann et al., 2005, ch. 3). A

link Evaluation rule then combines the two formulae on the

linked nodes using generalised semantic conjunction, here yielding

as the evaluated output. The problem arises with respect to

values. Since

Gordon is parsed first, it will host the conjoined formula, but the node is decorated with the masculine singular

value.

Substitution, as defined above, will entail an interpretation of

Gordon and Sarah said he was not going to the USA this year to mean

Gordon and Sarah said Gordon and Sarah were not going to the USA this year because the

values of

he and that of the head node of the

link structure match, and the latter, after evaluation, has as

value the conjoined individual terms. A solution would be to modify the

link Evaluation rule to not only combine the

linked formulae but also to non-monotonically replace the masculine

value with the third plural one. This would allow the straightforward substitution of the conjoined formula for the metavariable projected by the parse of a third plural pronoun without the need to resort to pragmatics. In turn, however, this will pose another problem. In an example like

Gordon and Sarah said they were not going to the USA this year, because he despises the current administration, substituting

(

) for

is no longer straightforward, as there would be no masculine singular

value for

Substitution to target, and a pragmatic strategy would be needed to satisfy the formula requirement of

he by means of the male implicature of the pronoun to identify Gordon as the antecedent. So it seems that one way or another, there does need to be a semantic/pragmatic means of construing anaphors in addition to the purely mechanical approach taken above. My preference in the current instance is to proceed with the non-monotonic modification to

Conjunction link Evaluation as envisaged above for two reasons. Firstly, my intuition is that the example with anaphoric

he requires the word to be stressed, which generally induces the hearer to infer that some pragmatic process is involved in identifying the antecedent (possibly indicating some contrast with Sarah). Secondly, the modification does not give rise to problems in unacceptable interpretations of singular pronouns with plural referents. The non-monotonicity of the replacement of one

value with another, though not ideal, nevertheless occurs in other instances of ‘disagreement’, such as the use of plural verbs with group-denoting singular nouns in British English, and the use of mass determiners with count nouns and vice versa, as discussed below.

Before moving on to an analysis of nominal agreement in English, it is important to note that my analysis of gender and number agreement of anaphors and antecedents makes no reference at all to any notions of gender or number as reified categories within the grammar. Although I refer to masculine or plural values, the grammar itself is blind to such concepts. All that the grammar encodes are collocational restrictions between nouns and pronouns, learned, I assume, during successful linguistic interactions during the language acquisition process. I return to this topic briefly at the end of the paper.

3.2. Nominal Agreement

The treatment of anaphoric agreement of the previous section provides many of the means to ensure agreement between nouns and verbs and determiners and nouns. I begin by reviewing the properties of nominal selection by determiners as in (20):

13| (20) | Determiner Agreement: |

| a. | this, that, every all select for singular nouns: a dog/*dogs, this computer/*computers, that announcement/*announcements. |

| b. | a(n) selects for singular count nouns: an owl, #a rice. |

| c. | these, those, many, fewer etc. select plural count nouns: these words/*word, those trends/*trend, many thoughts/*thought, fewer mistakes/*mistake. |

| d. | much, less select for singular mass nouns: much rice, #much human, less fussing, ??less eye. |

| e. | more selects for singular mass nouns and plurals: more food, more dogs/#dog. |

| f. | the, some, any and the genitive pronouns have no selection requirements: the dog/dogs/rice, some idea/ideas/furniture. |

To analyse the determiners that are sensitive only to number such as the demonstratives, we can simply assume that they decorate their dominating term node with a requirement for an

value of the appropriate sort: either

ɪ,t

ɪ,t,s

ʃ,i

h,ə,r

h,i

h,ɪ,m

h,ɪ,z

for singular or

ð,ei

ð,ɛ,m

ð,ɛ,r

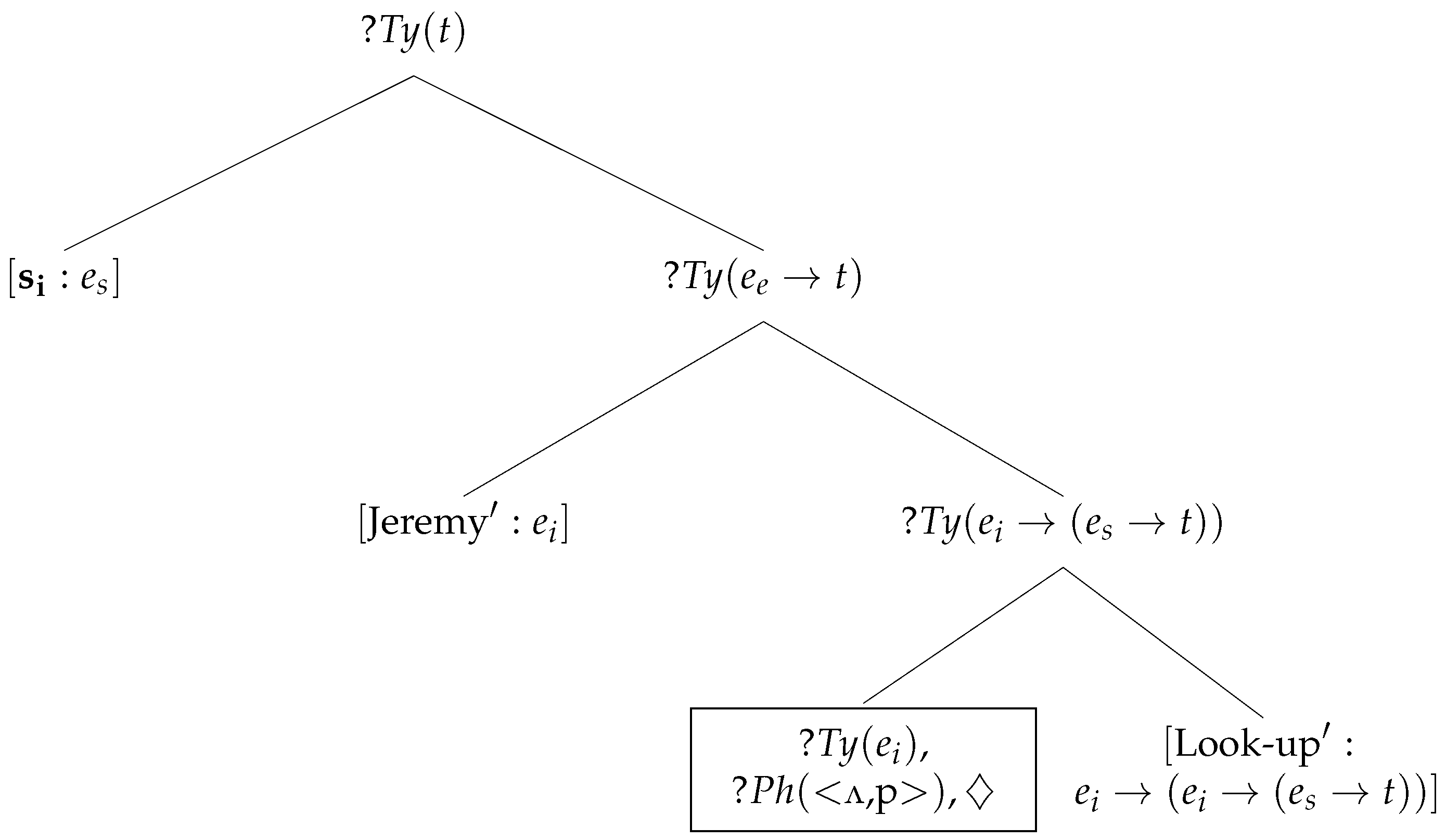

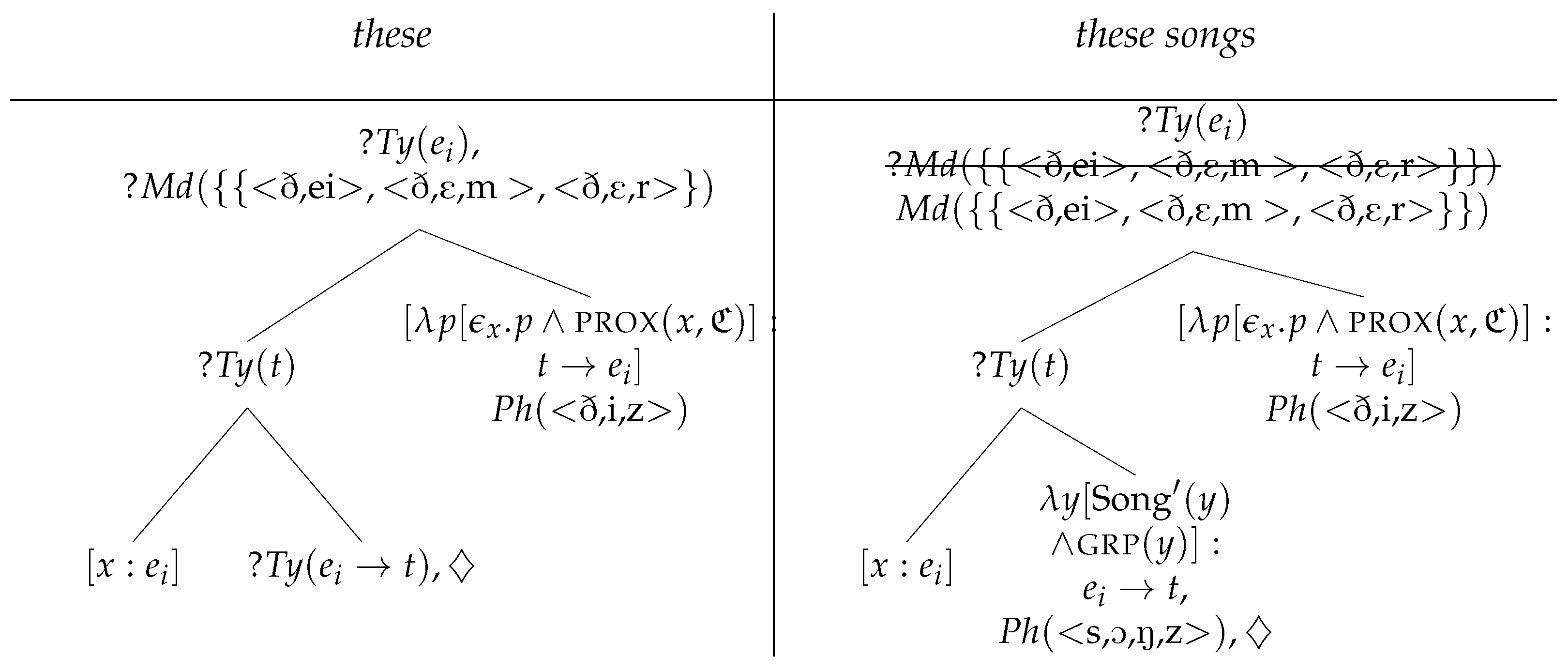

for plural. So we have analyses like the one shown in

Figure 6 for

these songs.

14As the

value projected by the noun matches that of the requirement,

Thinning applies to eliminate the requirement (indicated by strikethrough). However, for singular NPs like

this song or

that bull, matters are not so straightforward, as the values projected by the nouns may not exactly match those of the requirement, as nouns only project the relevant set of pronominal forms to ensure correct anaphoric relations. So,

song projects only third singular neuter values and

bull third singular neuter and masculine singular ones. In order to eliminate the requirement, the rule of

Thinning must be revised to allow a projected

value that subsumes the requirement value to satisfy the requirement. This is sufficient to allow the acceptable combination of singular demonstratives with singular nouns and exclude singular forms in combination with plural ones:

*this dogs,

*those song. (21) provides the appropriate rule with

standing for any label:

| (21) | Thinning |

| IF | | |

| THEN | IF | |

| | THEN | Delete |

| | ELSE | Abort |

| ELSE | Abort | |

The use of the personal pronominal forms as

values is sufficient to capture simple number agreement between determiners and their collocated nouns. However, when it comes to characterising the mass/count distinction, this is not sufficient, as all common nouns are third person, so there must be some other forms that differentiate them. There is much ink spilled in discussing the difference between count nouns and mass nouns, principally from a semantic perspective (

Bunt, 1985;

Link, 1983;

Gillon, 1992,

1999;

Meulen, 1981;

Joosten, 2003;

Moltmann, 1998;

Nicolas, 2002, amongst many others). While there is undoubtedly a human cognitive ability to conceptualise objects in terms of individuation or substance, semantic accounts of mass and count terms are controversial. One of the problems is the arbitrariness within any language and certainly cross-linguistically in terms of which nouns are treated as typically mass or count. This makes a universal characterisation of the distinction problematic, if not impossible. There is, for example, no ontological reason why

rice but not

bean is mass (cf, earlier English mass noun

pease from which the count noun

pea/peas is derived by back-formation) or why

hair should be mass in English but

cheveux should be count in French. Fortunately, to account for determiner agreement per se, we can leave aside any serious discussion of the various semantic theories and only consider morpho-syntactic behaviour, at least with respect to the common usage of nouns as mass or count.

Because of the arbitrary way nouns are treated as mass or count, the distinction can really only be determined by the most common syntactic behaviour of a given noun in a given language, dialect or sociolect.

Bloomfield (

1935) provides a set of morpho-syntactic properties of different nouns in English. These are summarised in

Bale and Barner (

2018, p. 4) and reproduced in (22):

| (22) | a. | Singular–Plural Contrast: Count nouns have alternate forms corresponding to singular and plural. Most mass nouns only have a singular form (though there are some with only a plural form). |

| b. | Antecedents: Only noun phrases headed by count nouns in the singular serve as antecedents for the pronouns another and one. |

| c. | Quantifier Distribution: The indefinite article a, the determiners each, every, either and neither and the cardinal numeral one modify only count nouns in the singular. The determiners few, a few, fewer, many and several and the cardinal numerals greater than or less than one modify only count nouns in the plural. The determiners all, enough and more may modify mass nouns or plural count nouns, but not singular count nouns; and mass nouns and plural count nouns, but not singular count nouns, may occur without a determiner. The quantifiers little, a little, less and much modify only mass nouns. |

Building on this description, a morpho-syntactic approach is proposed here using the

label. Common nouns, in addition to being associated with third person pronominal forms, must also record the sorts of determiners that they are typically collocated with, without any need for further inferential processing. Consider singular count nouns which all require a determiner, and the only non-general determiners (like the definite and demonstrative ones) they can appear with are, as noted above, the indefinite article,

each, every, neither, either and

one. So, including the two associated anaphoric forms in (22b), the associated

value of count nouns is as follows:

| (23) | Singular count nouns: |

| əə,ni,tʃɛ,v,r,iw,ʌ,nə,n,ʌ,θ,ə,rn,i,ð,ə,ri,ð,ə,r |

As this is rather unwieldy, I will abbreviate this value as

countsg in the discussion that follows, and I will abbreviate the third person singular

value as

3sg. Note that these are just abbreviations for sets of phonological forms not grammatical categories as such.

15The analysis of count and mass noun phrases differs from that of demonstrative ones, although the basic idea is the same. All mass and count determiners follow the same general procedures, which involve the projection of a requirement for third person while at the same time asserting an value that consists of the phonological form of the individual determiner and a metavariable with which it unifies. Thus, each will decorate the top term node with i,tʃ. The function of this metavariable is discussed below.

In addition, a more complex set of actions has to be associated with the parse of a common noun. In addition to projecting a person

value on the top term node, the actions check for an existing

value on that node. If there is one, a requirement

countsg) is imposed to ensure that the existing

value is that of a singular count determiner. Then, the pointer returns to the nominal predicate node and adds formula, type and

values as normal. If there is no

value, such as with the definite article and the demonstratives, no requirement for a singular count determiner is imposed, and type, formula and

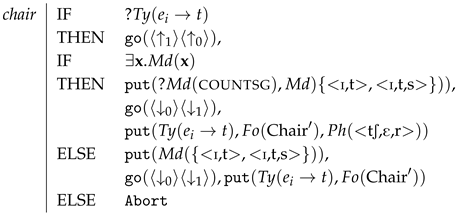

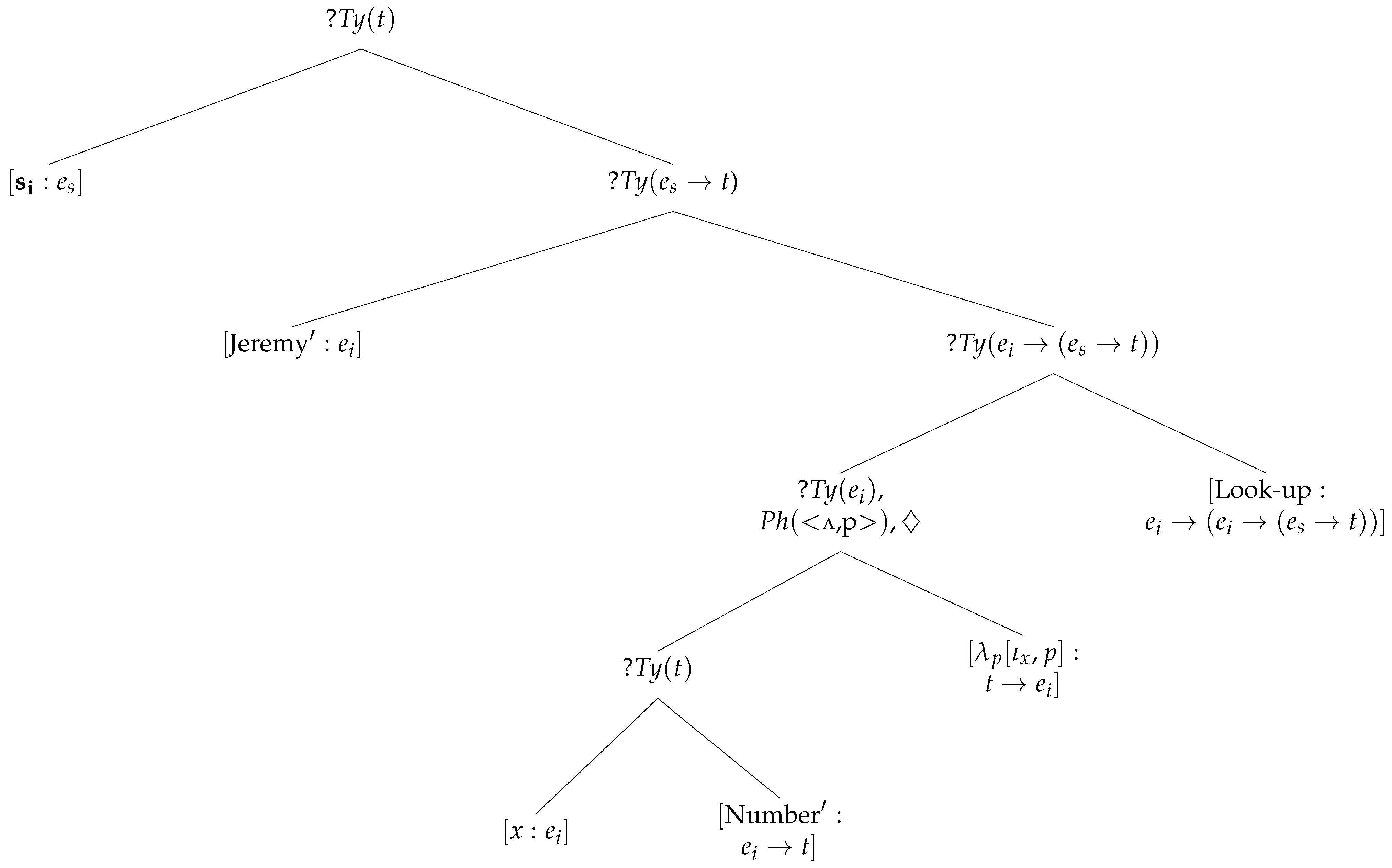

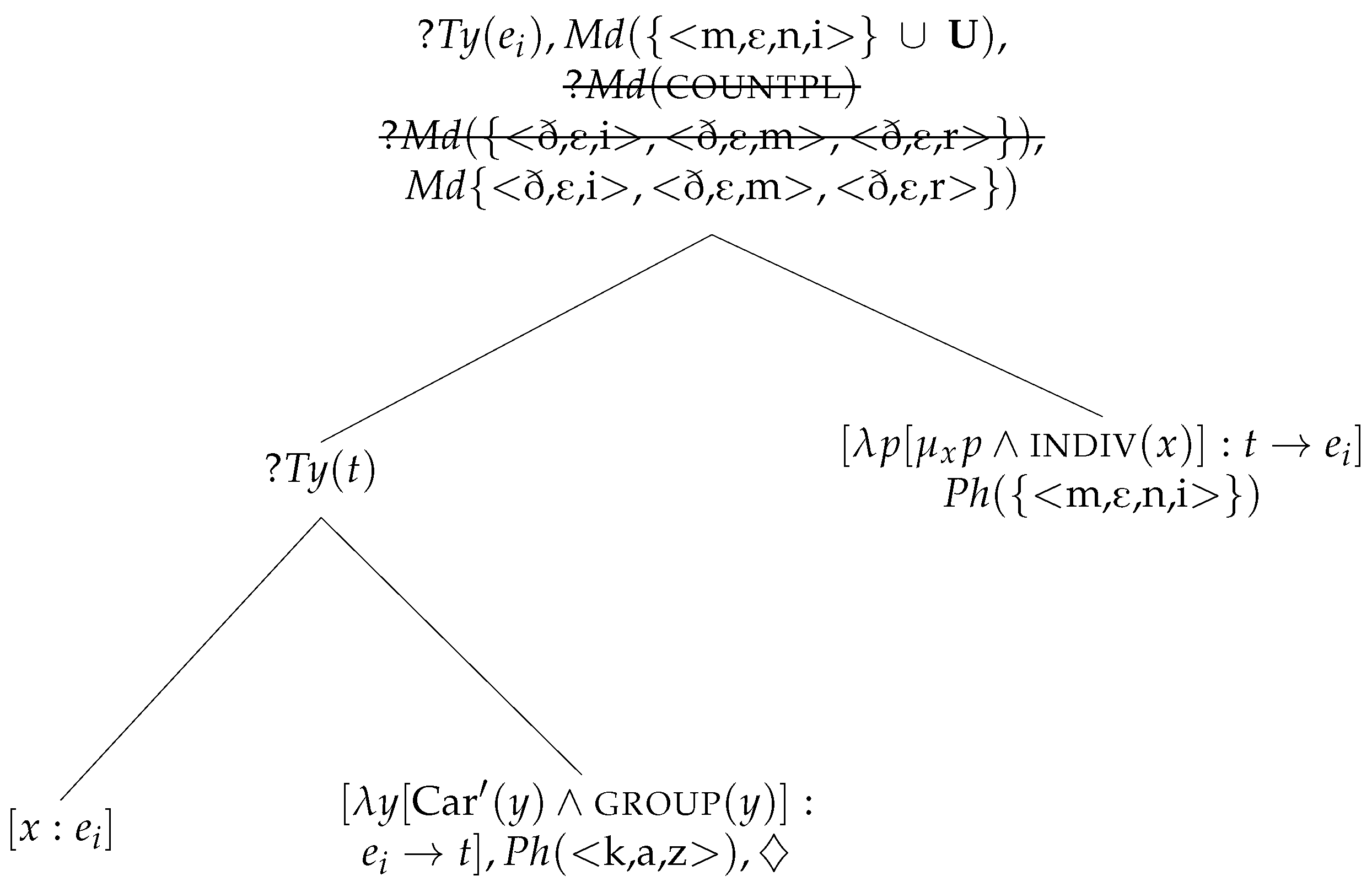

values are asserted. The actions associated with parsing

chair are thus as given in (24), and taking the count noun

chair and the indefinite article as exemplars,

Figure 7 illustrates the parse of the noun phrase

a chair.

| (24) | ![Languages 10 00289 i006 Languages 10 00289 i006]() |

Note that I am assuming that the determiner encodes an individuating predicate

indiv, following

Allan (

1980)’s division of determiners into individuating and non-individuating types which can be defined within

Link (

1983)’s lattice-theoretic semantics of plural and mass terms.

In the second tree, on the top node, there are two

requirements and two values. Both requirements can be eliminated straightforwardly through subsumption, as discussed above, but after compilation, this node contains two non-subsuming

values,

ɪ,t

ɪ,t,s

and

ə

, which should abort the parse. This is where the metavariable projected by the determiner comes into play. If the third singular

value substitutes for the metavariable, then the resulting value,

ə

ɪ,t

ɪ,t,s

, is subsumed by the third neuter singular value. Given that a node may contain two different instances of the same label just in case one value subsumes the other, the analysis presented here is fully licensed by the grammar.

16Nouns that are typically used as mass terms are not associated with forms of the indefinite article, but they can be analysed similarly to singular count terms by referring to the forms of the mass determiners:

| (25) | Singular mass nouns (masssg): |

| l,ɛ,sm,ɔl,ɪ,t,li,n,ʌ,fm,ʌ,tʃ |

As with count NPs, singular mass determiners assert an

value containing its phonological form plus a metavariable and project a third person singular requirement. Mass nouns then check whether there is an

value on the top term node, adding a requirement

(

masssg) before projecting their associated

value and returning to the triggering node and decorating it with

, formula and type values. Again, if there is no initial

value on the top term node, then the pointer simply returns to the nominal predicate node and adds type, formula and

values. Hence, a parse of a mass NP like

less rice proceeds exactly as one of

a chair except for the different

requirement and with the determiner formula involving a predicate

subst, indicating that the entity referred to is a non-individuated substance (has m-parts in

Link (

1983)’s terminology).

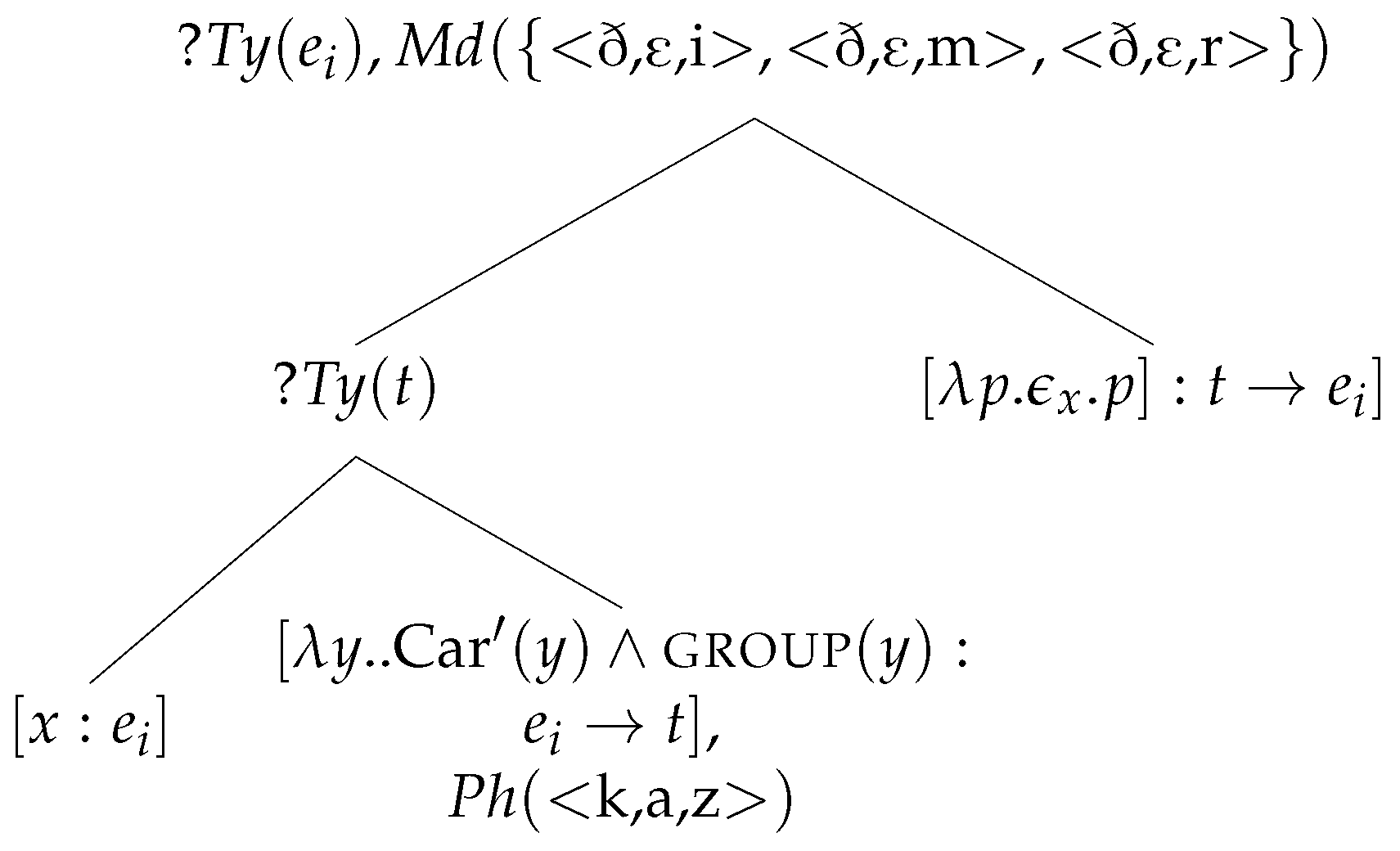

Plural count NPs like

many cars, several bushes, fewer children and the like can again be analysed in exactly the same way, despite, of course, showing different morphological dependencies. So plural NPs involve the annotation of the trigger node with its phonological form and metavariable as the

value and the plural requirement

ð,ɛ,i

ð,ɛ,m

ð,ɛ,r

, while building the internal structure of the term. Plural nouns then check for an

value on the top term node and, if found, add a plural determiner requirement

m,ɔ,r

f,j,u

f,j,u,w,ə,r

m,ɛ,n,i

s,ɛ,v,ə,r,ə,l

before adding formula,

and type values to the nominal predicate node.

Figure 8 shows the parse of

many cars before compilation, where

stands for whatever content is given to the operator provided by the determiner. As before, I am assuming that the third plural

value substitutes for the metavariable projected by the determiner to yield a single value for the top node

m,ɛ,n,i

ð,ɛ,i

ð,ɛ,m

ð,ɛ,r

.

Unlike singular count nouns but like singular mass nouns, plural count nouns can appear without any determiner at all. To handle these, I take the position that the parse of a plural count noun or a singular mass noun has two potential triggers: a predicate requirement constructed by the parse of a plural or mass determiner and a term requirement with no dominated nodes. In the latter environment, the parser constructs an epsilon operator and then builds the term as normal.

Figure 9 gives the structure of the term node after parsing

cars and the compiled output is

group(

x).

That, of course, is not the whole story of nominal agreement in English. Nouns typically used as mass terms can take individuating determiners, giving rise to interpretations as kinds or specified quantities (26), while at the same time, nouns typically used as count may appear in non-individuating contexts, giving rise to interpretations of substances of some inferred sort (27).

| (26) | Mass noun disagreement |

| a. | Three coffees, please. | [Quantity] |

| b. | That shop stocks at least a dozen coffees from all over the world. | [Kind] |

| c. | Every coffee seems to taste different. | [Quantity/Kind] |

| (27) | Count noun disagreement |

| a. | After the accident with the butcher’s van, there was a lot of pig all over the road. | [Meat] |

| b. | I could have done with less Martin in that meeting! | [Personality] |

| c. | My sister’s guide dog is more goat than dog. | [Property] |

The analyses of such examples yield trees that have a mismatch between

requirements and projected values, clashes that need to be resolved for the tree to compile. For example, the term node in (26c) will have the set of decorations in (28a), and that of (27a) will have that in (28b).

17| (28) | a. | ɛ,v,r,i

ɪ,tɪ,t,s} |

| b. | ə,l,ɔ,t,ə,v

ɪ,tɪ,t,s} |

What is needed is some sort of rule to delete the non-matching

requirement on the inconsistent term node and to modify the formula value. Of course, this violates the general DS condition that tree growth is monotonic. However, disagreement phenomena like those in (26) and (27), where there is always a semantic or strong pragmatic effect, is widespread enough cross-linguistically that it is necessary to countenance non-monotonic tree transitions in limited, specified contexts as a sort of ‘last resort’ mechanism. Rules that specify these transitions, which I will refer to as non-monotonic resolution rules, affect only a single node in a tree and license a new tree with modified decorations on that node.

The rule I propose for the resolution of mass-count disagreement is given in (29), where the symbol ⇝ indicates a non-monotonic tree transition:

18| (29) | |

| ⇝ |

| |

| where and . |

In the output, the offending requirement is eliminated and the formula value modified. The quantifier expressed by the determiner (

) is maintained and a contextual/pragmatic relation

is introduced that relates the bound variable to an epsilon term containing the property

P of the original formula (the property derived from the common noun phrase argument of the determiner). At the same time, the individual or substance predicate of the input formula is maintained. The pragmatic variable, which is not a metavariable as its value may never be realised, then relies on context in the broad sense for updating to an appropriate relation between a substance and an individual or vice versa. This rule yields the output for

every coffees in (30) and for

a lot of pig in (31).

| (30) | Every coffee |

| ɛ,v,r,iɪ,tɪ,t,s |

| (31) | A lot of pig |

| ə,l,ɔ,t,ə,vɪ,tɪ,t,s |

Exactly how is instantiated depends on many factors: the semantics of both noun and determiner, the context in which the utterance occurs and the interactional concerns of the speech participants. So with regard to the instances of coffee in the examples in (26), the first naturally gives rise to an interpretation ‘relevant portion of’ with exactly what portion that is being dependent on who the speaker is talking to and where they are. In a restaurant, the portion is likely to be a cup; in a takeaway a plastic or paper container; and in a friend’s house a mug. The same variability in precise interpretation applies to all examples of count–mass mismatch.

Not all nouns can be used felicitously as either count or mass. So

#much bean, #many admirations, #five waters, #less table, etc., are peculiar, although they could be acceptable given a rich enough context.

19 It is possible that frequency of use of certain determiners in certain contexts is involved in the acceptability of typically mass or count terms being used in atypical constructions. There is certainly a familiarity effect that makes some uses more acceptable than others. Thus, replacing instances of

coffee in (26) with

rice is less acceptable, although interpretable, while substituting

furniture is not really acceptable at all. Equally, not all count nouns are felicitous in non-individuating contexts, as illustrated in (32) and (33).

| (32) | a. | Three #rices/?*funitures, please. |

| b. | That shop stocks at least twenty not often seen #rices/*furnitures from all over the world. |

| c. | I won’t touch a #rice/*furniture in the evening. |

| (33) | a. | After the accident with the butcher’s van, there was a lot of #eagle/*seat all over the road. |

| b. | The room was buzzing, with ?*idea all over it. |

| c. | I could have done with less #chair/?*idea in that meeting! |

Resolution rules for plural mass terms and for singular count nouns appearing without a determiner do not involve non-monotonic tree transitions, as both must involve a new set of actions involved in parsing particular nouns. This is most obvious with plural mass terms which involve the addition of a plural morph to a mass noun, which would also necessitate a plural

value, a plural count

requirement and modification of a formula value. There is no theory of lexical processes in DS that I am aware of, but one might envisage a lexical process like that given in (34), where

stands for a macro of lexical actions:

| (34) | IF | |

| ɪ,tɪ,t,s |

| THEN | IF |

| THEN make-new |

| ELSE | Abort |

| ELSE | Abort |

| where | | IF | |

| THEN | |

| IF | |

| THEN | ð,eið,ɛ,mð,ɛ,r |

| | |

| | |

| | where szɪ,z |

| ELSE | Abort |

This rule checks to see if a lexical entry

contains a sequence of actions that moves the pointer up to a dominating open term node and adds a mass singular

requirement and a third neuter singular

value. If there is, there is a further check to see if there is an action that adds a predicate type, a formula

and phonological form

. If the condition is met, a new lexical entry is created whose actions are triggered on an open predicate node and involve the following: moving the pointer to the closest dominating open term node; checking if there is an

value; adding a plural count

requirement and a third plural

value, if an

value already decorates the node; and then finally moving the pointer down to the open predicate node, adding a predicate type value, a phonological form that appends a plural morph to

and a formula value that has a plural epsilon operator that binds a variable that is pragmatically related to an epsilon term whose restrictor is

.

This lexical rule would license a macro of lexical actions for the word

coffees, allowing the parse of phrases like

three coffees in exactly the same way as with

less coffee where the compiled formula value that results from a parse of the former is as follows:

Notice that this provides a lexical instantiation of the generalised resolution rule in (29), and it is possible that the rule is derived from repeated exposure to plural mass terms and allows an agent to essentially routinise encounters with particular terms used in this way, circumventing the need to apply the resolution rule every time the word in question is parsed or produced. A lexical approach would certainly explain the gaps in acceptable instances of mass–count disagreement, as illustrated above. Furthermore, such a lexical approach can be assumed to routinise all common instances of count–mass disagreement, leaving the resolution rule to apply only in novel or uncommon instances.

3.3. Verbal Agreement

As noted in the introduction, verbal agreement in English is limited to the present tense in main verbs,

have and

do, but is visible in both present and past with the copula

be. (35) provides a summary of the patterns:

| (35) | a. | Main verbs, have, do: Those forms marked by the suffix -s (and phonological variants) require a third person singular subject; unmarked base forms appear with third plural and first and second person subjects; forms in past tense allow any subject. |

| b. | Copula be: am requires a first person singular subject; is requires a third person singular subject; are requires a second person or plural first and third person subject; was requires a singular subject; were requires a second person or plural subject. |

| c. | Auxiliary verbs: These allow any subjects. |

The analysis of person and number agreement follows that of gender and number above: no categories as such, just sets of forms that collocate with other forms. Third person values are those already used for gender and number agreement, i.e., ɪ,tɪ,t,s, ʃ,ih,ə,r, and h,ih,ɪ,mh,ɪ,z for the singular and ð,e,ið,ɛ,rð,ɛ,r} for the plural. First and second person pronouns are again associated with values for their various forms: first singular aım,im,ai, first plural w,iʌ,sau,r and second j,uj,ɔ,r.

Under the analysis of auxiliary and main verbs in

Cann (

2011), tensed main verbs can only be parsed (or generated) in the context of there being a locally unfixed node that represents the content of the local subject, where locality as mentioned earlier indicates the minimal propositional structure containing the current node.

20 To handle agreement, verbal actions need to require such a node to be decorated with an appropriate

value. Third singular present tense verbs thus require any of the nominative third singular values on their subjects, which must form part of the triggering environment for a successful parse, as illustrated in the partial entry specifying the initial triggering environment for

sings in (36) (

is the ‘locally dominates’ modality associated with

Local*Adjunction; see

Cann et al., 2005, pp. 234 ff.).

21| (36) | sings | | | |

| IF | | | |

| THEN | IF | | |

| THEN | Abort | |

| ELSE | IF | |

| | | where ʃ,ih,iɪ,t |

| | THEN | [Other Actions] |

Conversely, finite base forms will require reference to nominative non-third person

values:

22| (37) | sing | | | |

| IF | | | |

| THEN | IF | | |

| THEN | Abort | |

| ELSE | IF | |

| | | where ð,eiaij,uw,i |

| | THEN | [Other Actions] |

The initial restriction in (36) and (37), which requires there to be a locally unfixed node that the trigger node dominates and which the verbal actions fix as the grammatical subject, means that there only needs to be a match with person

values. However, because of Subject Auxiliary Inversion,

have, do and

be lack this restriction. Instead, a parse of their forms induces the construction of a locally unfixed node on which the relevant

value is imposed, which must subsume, or be subsumed by, that projected by a subject nominal for the appropriate

value.

23The different forms of the copula

be are analysed similarly but involve different requirements, analogous to the description in (35b):

| (38) | a. | am projects ai. |

| b. | is projects ʃ,ih,iɪ,t. |

| c. | are projects j,uw,ið,ei |

| d. | was projects aiʃ,ih,iɪ,t. |

| e. | were projects j,uw,ið,ei |

Have and

do follow the pattern of the main verbs like

sing/sings above, except that they impose

values on the locally unfixed node that must subsume or be subsumed by that projected by a subject nominal as with

be.

To close this section, I turn to a short discussion of the one type of verbal disagreement in British English: the use of present tense base verb forms with group-denoting singular nouns as exemplified in (39).

| (39) | a. | The committee are currently considering your request. |

| b. | This flock of sparrows take to the air every evening at dusk. |

It seems that only definite NPs are truly felicitous in this context (my acceptability judgements):

| (40) | a. | ?No committee make decisions on a Thursday. |

| b. | *A committee are considering your appeal. |

| c. | *Every committee make decisions on a Thursday. |

Note that anaphoric reference to these examples requires the plural third person pronoun:

| (41) | The committee are considering your application. They/*it usually meet on Mondays to make final decisions. |

It is clear that what we have here is a case of semantic agreement as

they picks out the group of entities that comprise the denotation of the noun, and again, some rule is needed to resolve the clash of

values and to provide a semantic representation of the effect of the morphological disagreement. In the current case, I propose the non-monotonic resolution rule in (42), which again uses ⇝ to indicate such tree growth:

24| (42) | j,uw,ið,eiɪ,tɪ,t,s |

| ⇝ |

| ð,e,ið,ɛ,mð,ɛ,r |

This rule essentially deletes the original

values projected by the noun and verb, replacing them with the third person plural value, while at the same time altering the original formula to pick out a group of individuals whose atomic parts (

) are all atomic parts of the object denoted by the original iota term. Under the assumption that the predicate

group requires there to be at least two entities, this semantic representation ensures that only group-denoting nouns can be resolved in this way and that it may only be a subset of the relevant group that engages in the event expressed by the rest of the sentence. Hence, (39) could be true even if not all members of the committee actually do consider the applications.