Effects of Light Quality on Flowering and Physiological Parameters of Cymbidium ensifolium ‘Longyan Su’

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Effects of Light Quality on Flowering Time and Inflorescence Flowering Duration in C. ensifolium

2.2. Effect of Light Quality on the Flower Quality of C. ensifolium

2.3. Effects of Light Quality on on Chlorophyll Content in C. ensifolium Leaves

2.4. Effects of Light Quality on Soluble Protein and Soluble Sugar in C. ensifolium Leaves

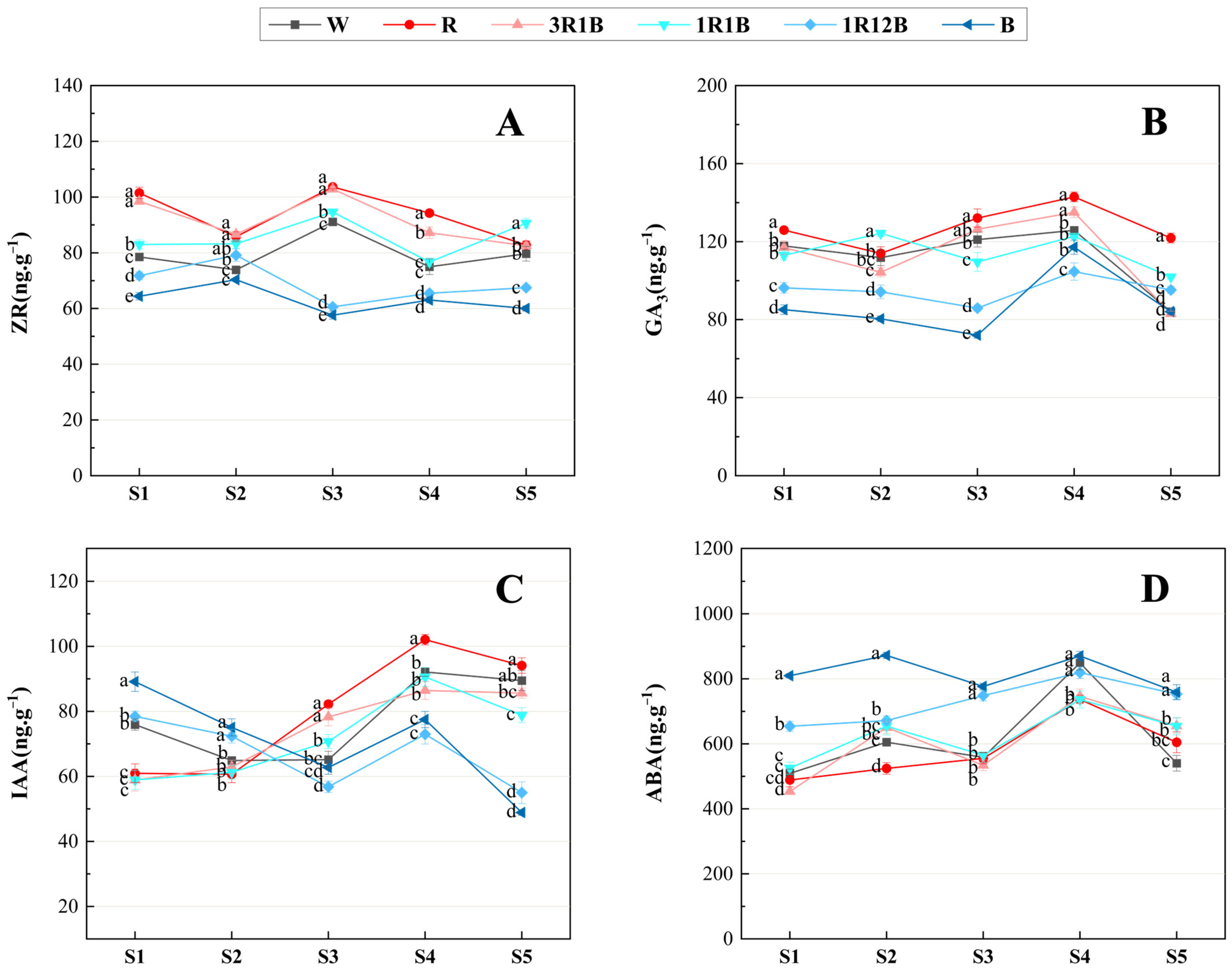

2.5. Effects of Light Quality on the Endogenous Hormone Content in C. ensifolium Leaves

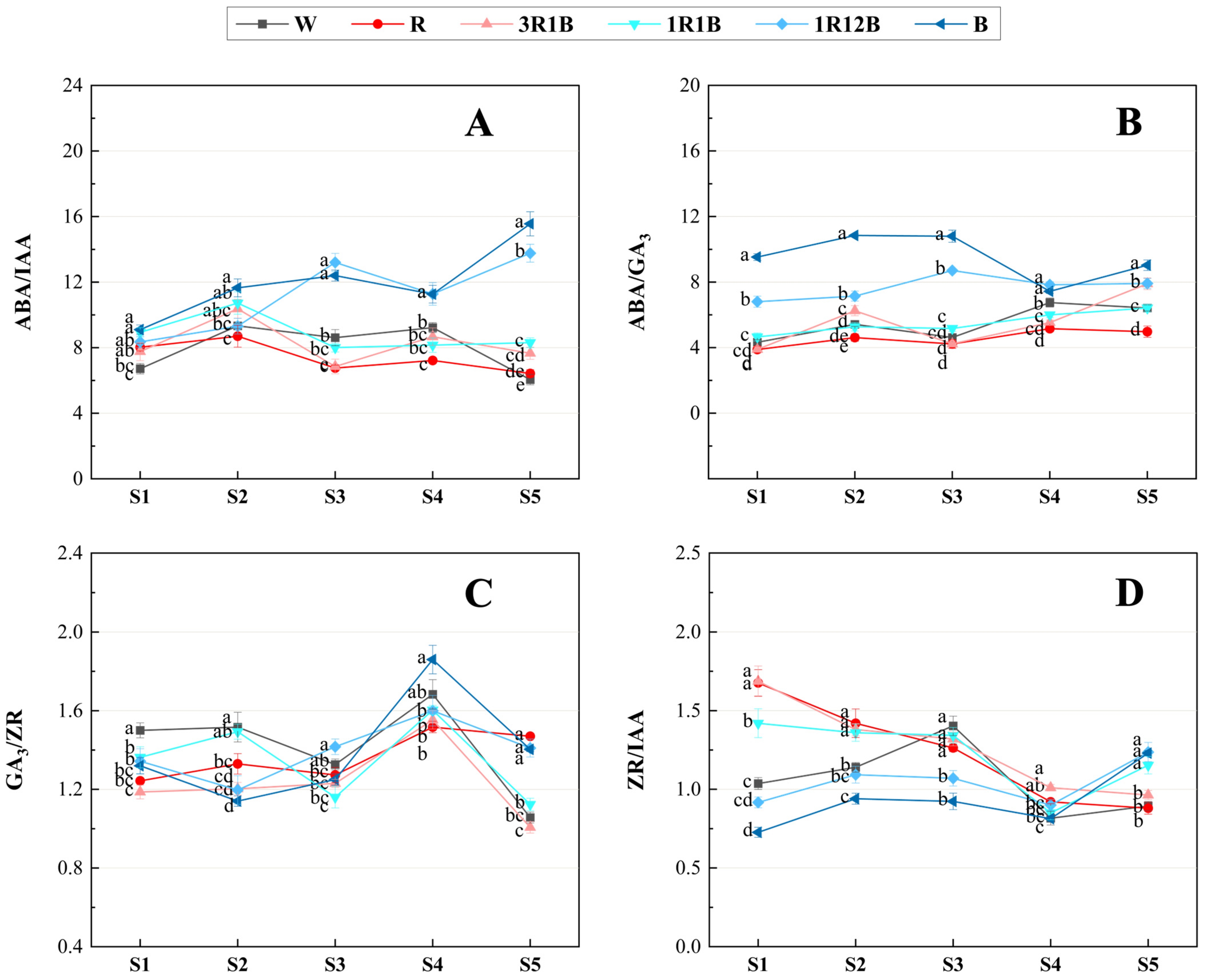

2.6. Effects of Light Quality on Endogenous Hormone Ratios in C. ensifolium Leaves

3. Discussion

3.1. Influence of Light Quality on Flowering Time and Flower Quality of C. ensifolium

3.2. Influence of Light Quality on Soluble Protein and Soluble Sugar Contents in Leaves of C. ensifolium

3.3. Influence of Light Quality on Hormone Contents in Leaves of C. ensifolium

4. Materials and Methods

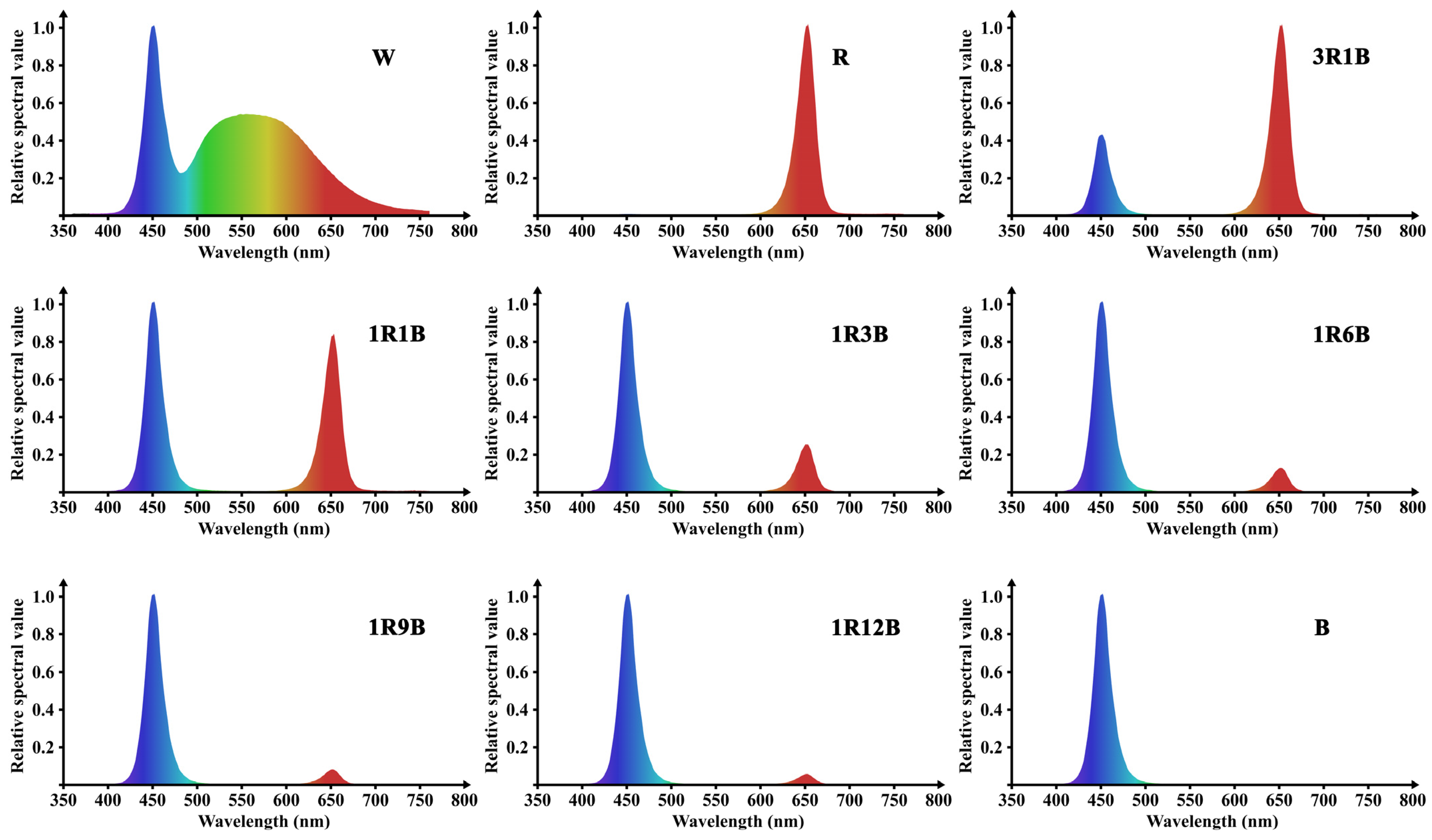

4.1. Experimental Material Schemes

4.2. Experimental Treatments

4.3. Recording of Flowering Time and Inflorescence Flowering Duration

4.4. Measurement of Flowering Quality Indicators

4.5. Measurement of Plant Physiological Parameters

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ramya, M.; Park, P.H.; Chuang, Y.C.; Kwon, O.K.; An, H.R.; Park, P.M.; Baek, Y.S.; Kang, B.C.; Tsai, W.C.; Chen, H.H. RNA sequencing analysis of Cymbidium goeringii identifies floral scent biosynthesis related genes. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, A.; Chen, Z.; Ma, J.; Liu, D.; Escalona, V.H.; Qian, G.; Yu, X.; Huang, H.; et al. Integrated metabolome and transcriptome analysis revealed color formation in purple leaf mustard (Brassica juncea). Sci. Hortic. 2024, 337, 113526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvão, V.C.; Fankhauser, C. Sensing the light environment in plants: Photoreceptors and early signaling steps. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2015, 34, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Xu, A.; Cheng, Z. Effects of light emitting diode lights on plant growth, development and traits a meta-analysis. Hortic. Plant J. 2021, 7, 552–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.; Huang, M.; Hsu, M. Morphological and physiological response in green and purple basil plants (Ocimum basilicum) under different proportions of red, green, and blue LED lightings. Sci. Hortic. 2021, 275, 109677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Sun, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Xu, Y.; Liu, B.; Li, Q. Effects of Red and Blue Light on the Growth, Photosynthesis, and Subsequent Growth under Fluctuating Light of Cucumber Seedlings. Plants 2024, 13, 1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clack, T.; Mathews, S.; Sharrock, R.A. The phytochrome apoprotein family in Arabidopsis is encoded by five genes: The sequences and expression of PHYD and PHYE. Plant Mol. Biol. 1994, 25, 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aalifar, M.; Aliniaeifard, S.; Arab, M.; Zare Mehrjerdi, M.; Dianati Daylami, S.; Serek, M.; Woltering, E.; Li, T. Blue Light Improves Vase Life of Carnation Cut Flowers Through Its Effect on the Antioxidant Defense System. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ait-Ali, T.; Frances, S.; Weller, J.L.; Reid, J.B.; Kendrick, R.E.; Kamiya, Y. Regulation of gibberellin 20-oxidase and gibberellin 3beta-hydroxylase transcript accumulation during De-etiolation of pea seedlings. Plant Physiol. 1999, 121, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trouwborst, G.; Hogewoning, S.W.; van Kooten, O.; Harbinson, J.; van Ieperen, W. Plasticity of photosynthesis after the ‘red light syndrome’ in cucumber. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2016, 121, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Chen, L.; Liang, R.; Huang, S.; Li, X.; Huang, B.; Luo, H.; Zhang, M.; Wang, X.; Zhu, H. The role of light in regulating plant growth, development and sugar metabolism: A review. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1507628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowska, R.; Hanus-Fajerska, E.; Kamińska, I.; Koźmińska, A.; Długosz-Grochowska, O.; Kapczyńska, A. High ratio of red-to-blue LED light improves the quality of Lachenalia ‘Rupert’ inflorescence. Folia Hortic. 2019, 31, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, W.G.; Meng, Q.; Lopez, R.G. Promotion of Flowering from Far-red Radiation Depends on the Photosynthetic Daily Light Integral. HortScience 2018, 53, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.; Lee, C.; Hosakatte, N.; Paek, K. Influence of light quality and photoperiod on flowering of Cyclamen persicum Mill. cv. ‘Dixie White’. Plant Growth Regul. 2003, 40, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, S.; Kafi, M.; Aliniaeifard, S.; Moosavi-Nezhad, M.; Pedersen, C.; Gruda, N.; Salami, S.A. Monochromatic blue light enhances crocin and picrocrocin content by upregulating the expression of underlying biosynthetic pathway genes in saffron (Crocus sativus L.). Front. Hortic. 2022, 1, 960423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharti Magar, Y.; Noguchi, A.; Furufuji, S.; Kato, H.; Amaki, W. Effects of light quality during supplemental lighting on Phalaenopsis flowering. Acta Hortic. 2019, 1262, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Li, Z.; Shang, Z.; Zhao, L.; Bai, J.; Wang, Y. Effects of different light quality of LED on flowering of Dendrobium officinale Kimura et Migoin vitro. J. South. Agric. 2019, 50, 1550–1556. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Mo, L.; Zhang, W.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, H.; Wang, Z.; Song, X.; Meng, X. Different combinations of red and blue LED light affect the growth, physiology metabolism and photosynthesis of in vitro-cultured Dendrobium nobile ‘Zixia’. Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 2023, 64, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Wang, G.; Yao, C.; Xing, Q.; Xie, J.; Huang, Z.; Pu, S.; Fan, Y.; Luo, A. Effect of Light Quality on Morphological and Physiological Indexes of Dendrobium denneanum. J. Sichuan For. Sci. Technol. 2022, 43, 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Wei, Q.; Li, C.; Jiang, C.; Zhang, H. Comparative Proteomic Analysis Provides Insights into the Regulation of Flower Bud Differentiation in Crocus sativus L. J. Food Biochem. 2016, 40, 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, D.; Ding, M.; Tang, F.; Mo, R.; Teng, Y. Determination of Four Endogenous Phytohormones in Bamboo Shoots by Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Chin. J. Anal. Chem. 2013, 41, 1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Chen, Q.; Callow, P.; Mandujano, M.; Han, X.; Cuenca, B.; Bonito, G.; Medina-Mora, C.; Fulbright, D.W.; Guyer, D.E. Efficient Micropropagation of Chestnut Hybrids (Castanea spp.) Using Modified Woody Plant Medium and Zeatin Riboside. Hortic. Plant J. 2021, 7, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rademacher, W. Plant Growth Regulators: Backgrounds and Uses in Plant Production. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2015, 34, 845–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, B.; Zhu, J.; Kong, X.; Ding, Z. Light participates in the auxin-dependent regulation of plant growth. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2021, 63, 819–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riboni, M.; Robustelli Test, A.; Galbiati, M.; Tonelli, C.; Conti, L. ABA-dependent control of GIGANTEA signalling enables drought escape via up-regulation of FLOWERING LOCUS T in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, 6309–6322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putterill, J.; Laurie, R.; Macknight, R. It’s time to flower: The genetic control of flowering time. BioEssays News Rev. Mol. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2004, 26, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibuya, T.; Kanayama, Y. Flowering response to blue light and its molecular mechanisms in Arabidopsis and horticultural plants. Adv. Hort. Sci. 2014, 28, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Zheng, Y. Complex Signaling Networks Underlying Blue-Light-Mediated Floral Transition in Plants. Plants 2025, 14, 1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, N.; Ajima, C.; Yukawa, T.; Olsen, J.E. Antagonistic action of blue and red light on shoot elongation in petunia depends on gibberellin, but the effects on flowering are not generally linked to gibberellin. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2016, 121, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, X.; Liu, X.; Xue, J.; Ren, X.; Zhai, Y.; Zhang, X. The red/blue light ratios from light-emitting diodes affect growth and flower quality of Hippeastrum hybridum ‘Red Lion’. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1048770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.G.; Jeong, B.R. Night interruption light quality changes morphogenesis, flowering, and gene expression in Dendranthema grandiflorum. Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 2019, 60, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukamoto, A.; Hirai, T.; Chin, D.P.; Mii, M.; Mizoguchi, T.; Mizuta, D.; Yoshida, H.; Olsen, J.E.; Ezura, H.; Fukuda, N. The FT-like gene PehFT in petunia responds to photoperiod and light quality but is not the main gene promoting light quality-associated flowering. Plant Biotechnol. 2016, 33, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajdu, A.; Dobos, O.; Domijan, M.; Bálint, B.; Nagy, I.; Nagy, F.; Kozma-Bognár, L. Elongated Hypocotyl 5 mediates blue light signalling to the Arabidopsis circadian clock. Plant J. 2018, 96, 1242–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Z.; Heng, Y.; Bian, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhao, X.; Jiang, Y.; Deng, X.W.; Xu, D. BBX11 promotes red light-mediated photomorphogenic development by modulating phyB-PIF4 signaling. aBIOTECH 2021, 2, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.V.; Lucyshyn, D.; Jaeger, K.E.; Alós, E.; Alvey, E.; Harberd, N.P.; Wigge, P.A. Transcription factor PIF4 controls the thermosensory activation of flowering. Nature 2012, 484, 242–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Yamaguchi, S.; Lim, S.; Oh, E.; Park, J.; Hanada, A.; Kamiya, Y.; Choi, G. SOMNUS, a CCCH-type zinc finger protein in Arabidopsis, negatively regulates light-dependent seed germination downstream of PIL5. Plant Cell 2008, 20, 1260–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xu, Z.; Tang, C. Effect of light-emitting diodes on growth and morphogenesis of upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) plantlets in vitro. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2010, 103, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; He, H.; Song, W. Application of Light-emitting Diodes and the Effect of Light Quality on Horticultural Crops: A Review. HortScience 2019, 54, 1656–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.; Qi, Y.; Wang, Y.N.; Wang, C.Z.; Zhu, J.; Wang, C.P.; Ma, L.; Zhang, J.H.; Lv, X.H. Screening of flower bud differentiation conditions and changes in metabolite content of Phalaenopsis pulcherrima. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2024, 171, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S. Mechanism of Flower Development and Early Flowering Technique of Cymbidium sinense. Master’s Thesis, Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, Fuzhou, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Luo, T.; Zhang, H.; Shao, J.; Peng, J.; Sun, J. Variation of Endogenous Hormones during Flower and Leaf Buds Development in ‘Tianhong 2’ Apple. HortScience 2020, 55, 1794–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, W.G.; Ramireddy, E.; Heyl, A.; Schmülling, T. Gene regulation by cytokinin in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2012, 3, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mornya, P.M.P.; Cheng, F. Effect of Combined Chilling and GA3 Treatment on Bud Abortion in Forced ‘Luoyanghong’ Tree Peony (Paeonia suffruticosa Andr.). Hortic. Plant J. 2018, 4, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurepin, L.V.; Emery, R.J.; Pharis, R.P.; Reid, D.M. Uncoupling light quality from light irradiance effects in Helianthus annuus shoots: Putative roles for plant hormones in leaf and internode growth. J. Exp. Bot. 2007, 58, 2145–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yu, X.; Foo, E.; Symons, G.M.; Lopez, J.; Bendehakkalu, K.T.; Xiang, J.; Weller, J.L.; Liu, X.; Reid, J.B.; et al. A study of gibberellin homeostasis and cryptochrome-mediated blue light inhibition of hypocotyl elongation. Plant Physiol. 2007, 145, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aalifar, M.; Aliniaeifard, S.; Arab, M.; Mehrjerdi, M.Z.; Serek, M. Blue light postpones senescence of carnation flowers through regulation of ethylene and abscisic acid pathway-related genes. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 151, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Zheng, Y. Multiple Signals Can Be Integrated into Pathways of Blue-Light-Mediated Floral Transition: Possible Explanations on Diverse Flowering Responses to Blue Light Manipulation. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, P.; Wang, W.; Guo, Y.; Hao, X.; Du, L.; Zhou, C. The Exploration of Flowering Mechanisms in Cherry Plants. Plants 2023, 12, 3980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Shi, Z.; Fu, X.; Zhao, P.; Tian, M.; Sun, D.; Wang, J. Flower Bud Differentiation and Endogenous Hormone Changes of Camellia ‘High Fragrance’. Mol. Plant Breed. 2024; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Gharti Magar, Y.; Ohyama, K.; Noguchi, A.; Amaki, W.; Furufuji, S. Effects of light quality during supplemental lighting on the flowering in an everbearing strawberry. Acta Hortic. 2018, 1206, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lymperopoulos, P.; Msanne, J.; Rabara, R. Phytochrome and Phytohormones: Working in Tandem for Plant Growth and Development. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, H.; Gu, W.; Wang, H.; Luo, M.; Zhao, Q.; Zhu, Z.; Xing, Y.; Song, Y. Dynamic Changes of Endogenous hormones in Vanilla Leaf during Flower Bud Differentiation. Chin. J. Trop. Agric. 2018, 38, 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Lian, X.; Wang, L. Study on the Regulation Mechanism of Endogenous Hormones in Delayed Flowering of Lonicera japonica. Acta Hortic. Sin. 2019, 46, 1399–1408. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Zeng, L.; Du, X.; Peng, Y.; Tao, Y.; LI, Y.; Qin, J. Flower Bud Differentiation and Endogenous Hormone Changes of Rosa ‘Angela’. Bull. Bot. Res. 2024, 41, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda, N.; Nishimura, S.; Nogi, M. Effects of localized light quality from light emitting diodes on geranium peduncle elongation. Acta Hortic. 2002, 580, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taixiang, X.; Rongrong, Y.; Juan, C.; Lu, C.; Ye, A. Photosynthetic Pigments Content and Chlorophyll Fluorescence Kinetics Parameters of a Leaf Mutant Cultivar of Cymbidium ensifolium. Subtrop. Plant Sci. 2019, 48, 232–236. [Google Scholar]

- Zahedi, S.M.; Hosseini, M.S.; Daneshvar Hakimi Meybodi, N.; Abadía, J.; Germ, M.; Gholami, R.; Abdelrahman, M. Evaluation of drought tolerance in three commercial pomegranate cultivars using photosynthetic pigments, yield parameters and biochemical traits as biomarkers. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 261, 107357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrololomi, S.M.J.; Raeini Sarjaz, M.; Pirdashti, H. The effect of drought stress on the activity of antioxidant enzymes, malondialdehyde, soluble protein and leaf total nitrogen contents of soybean (Glycine max L.). Environ. Stress Crop Sci. 2019, 12, 17–28. [Google Scholar]

| Treatments | Ratio (Red:Blue) | PPFD (μmol·m−2·s−1) | Photoperiod |

|---|---|---|---|

| W(CK) | white | 80 | 7:00–19:00 |

| R | red | 80 | 7:00–19:00 |

| 3R1B | red/blue = 3:1 | 80 | 7:00–19:00 |

| 1R1B | red/blue = 1:1 | 80 | 7:00–19:00 |

| 1R3B | red/blue = 1:3 | 80 | 7:00–19:00 |

| 1R6B | red/blue = 1:6 | 80 | 7:00–19:00 |

| 1R9B | red/blue = 1:9 | 80 | 7:00–19:00 |

| 1R12B | red/blue = 1:12 | 80 | 7:00–19:00 |

| B | blue | 80 | 7:00–19:00 |

| Measurement Indicators | Specific Methods |

|---|---|

| Flower scape length/cm | The distance from the base of the pseudobulb to the tip of the flower |

| Flower scape diameter/mm | The diameter of the internode between the first and second flower from bottom to top |

| Flower transverse diameter/cm | The maximum horizontal width of the second flower from the bottom |

| Flower longitudinal diameter/cm | The maximum vertical length of the second flower from the bottom |

| Floret spacing/cm | The distance between the first flower and the second flower from bottom to top |

| Number of flowers/n | The total number of flowers on a single flower scape |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xue, L.; Duan, Y.; Li, X.; Li, C.; Chen, X.; Wang, F.; Ji, Y.; Chen, J.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, Z.; et al. Effects of Light Quality on Flowering and Physiological Parameters of Cymbidium ensifolium ‘Longyan Su’. Plants 2025, 14, 3670. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233670

Xue L, Duan Y, Li X, Li C, Chen X, Wang F, Ji Y, Chen J, Jiang Y, Liu Z, et al. Effects of Light Quality on Flowering and Physiological Parameters of Cymbidium ensifolium ‘Longyan Su’. Plants. 2025; 14(23):3670. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233670

Chicago/Turabian StyleXue, Luyu, Yanru Duan, Xiuling Li, Chenye Li, Xiuming Chen, Fei Wang, Yulu Ji, Jinliao Chen, Yu Jiang, Zifu Liu, and et al. 2025. "Effects of Light Quality on Flowering and Physiological Parameters of Cymbidium ensifolium ‘Longyan Su’" Plants 14, no. 23: 3670. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233670

APA StyleXue, L., Duan, Y., Li, X., Li, C., Chen, X., Wang, F., Ji, Y., Chen, J., Jiang, Y., Liu, Z., Liu, N., & Peng, D. (2025). Effects of Light Quality on Flowering and Physiological Parameters of Cymbidium ensifolium ‘Longyan Su’. Plants, 14(23), 3670. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233670