Effects of Different Plant Growth Regulators on Growth Physiology and Photosynthetic Characteristics of Pinus koraiensis Seedlings

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

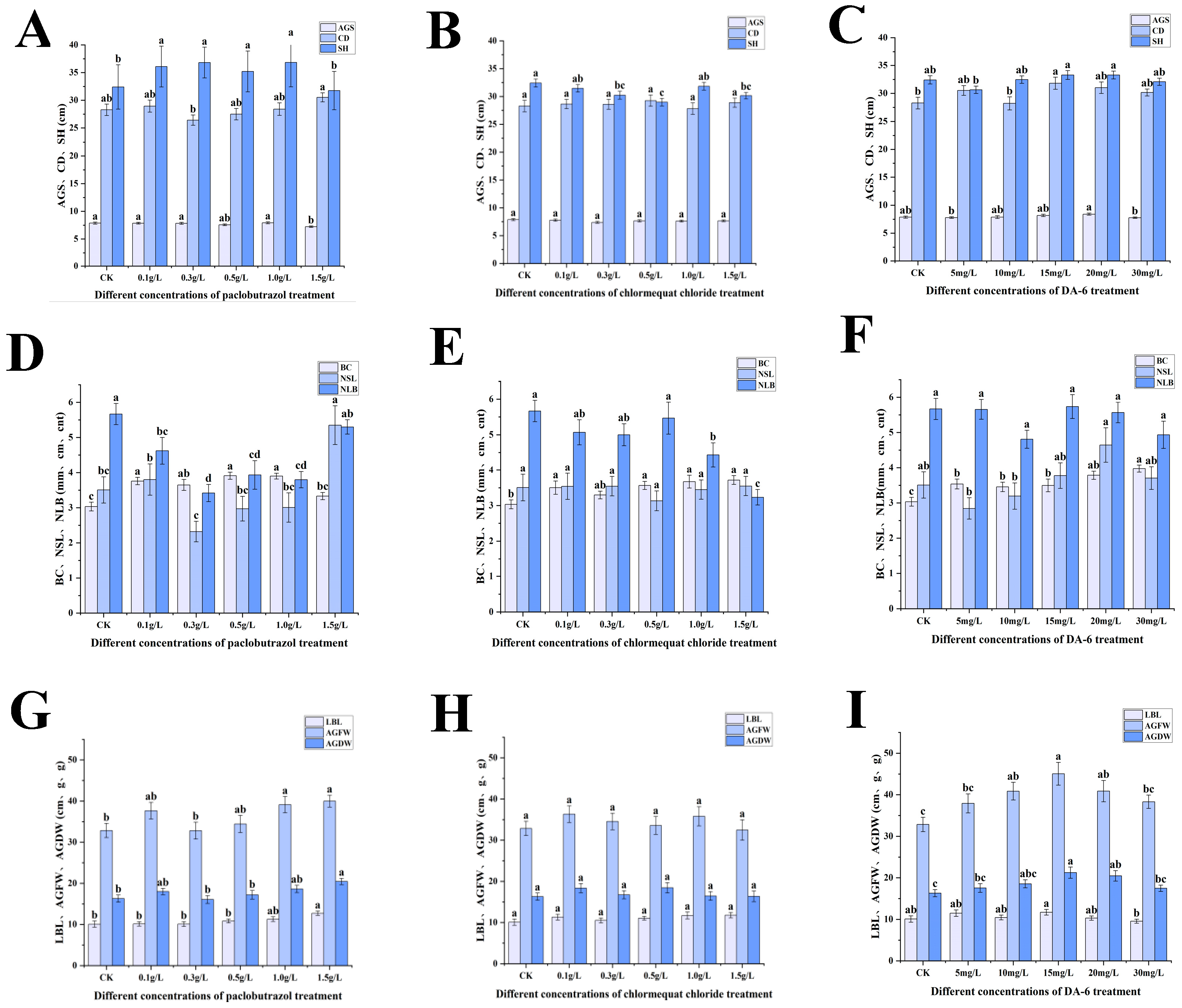

2.1. Growth Characteristics

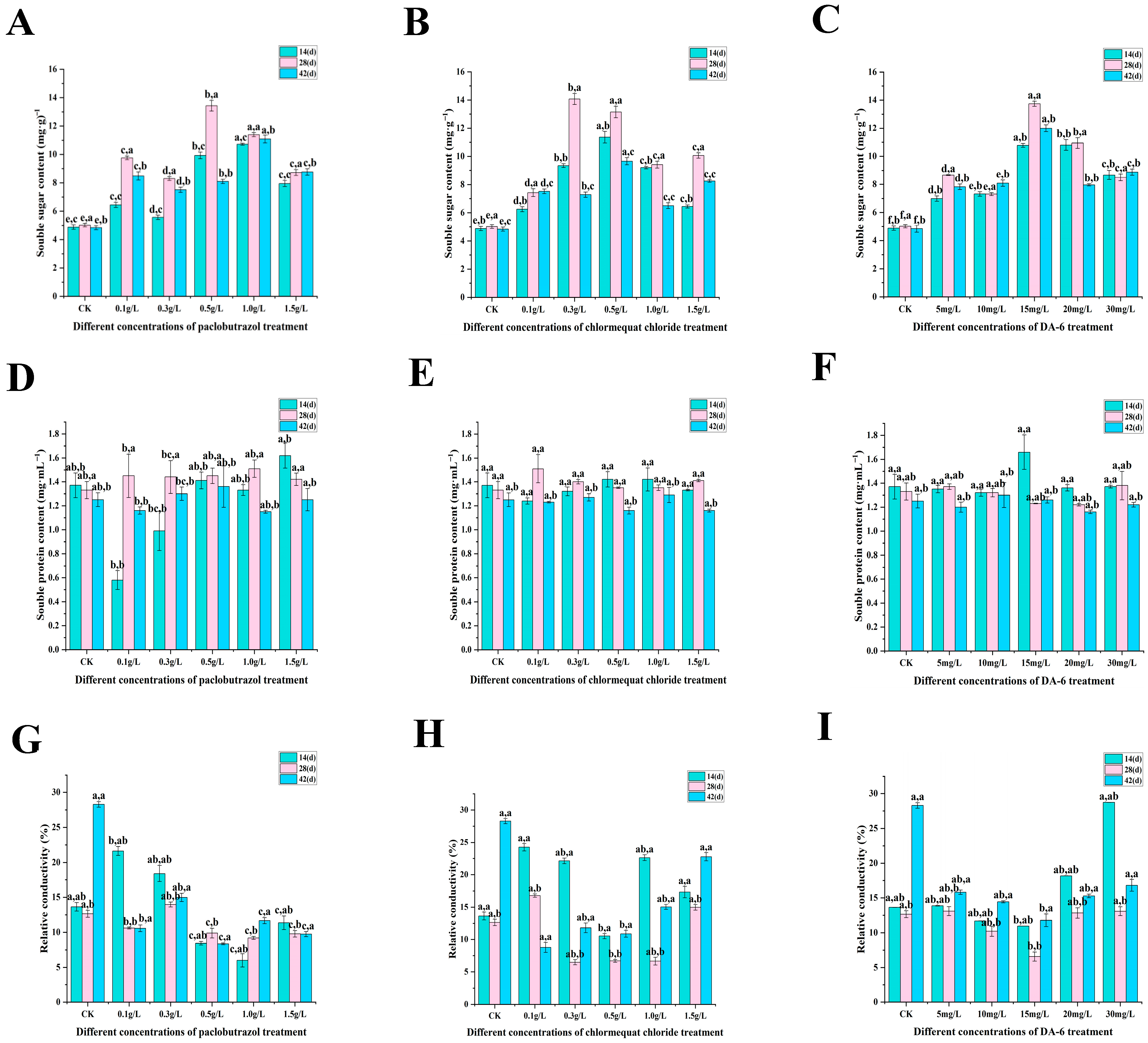

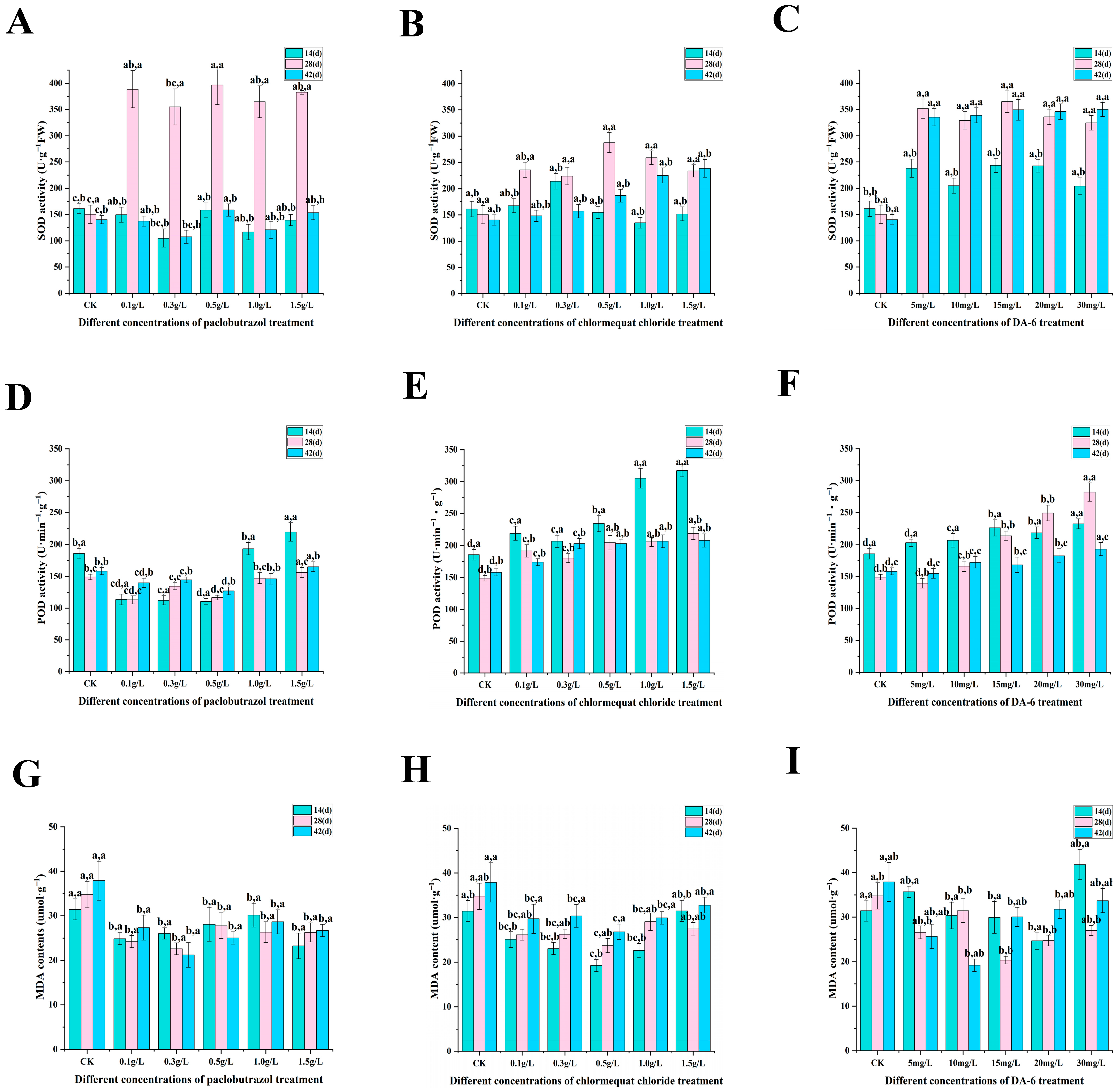

2.2. Physiological Characteristics

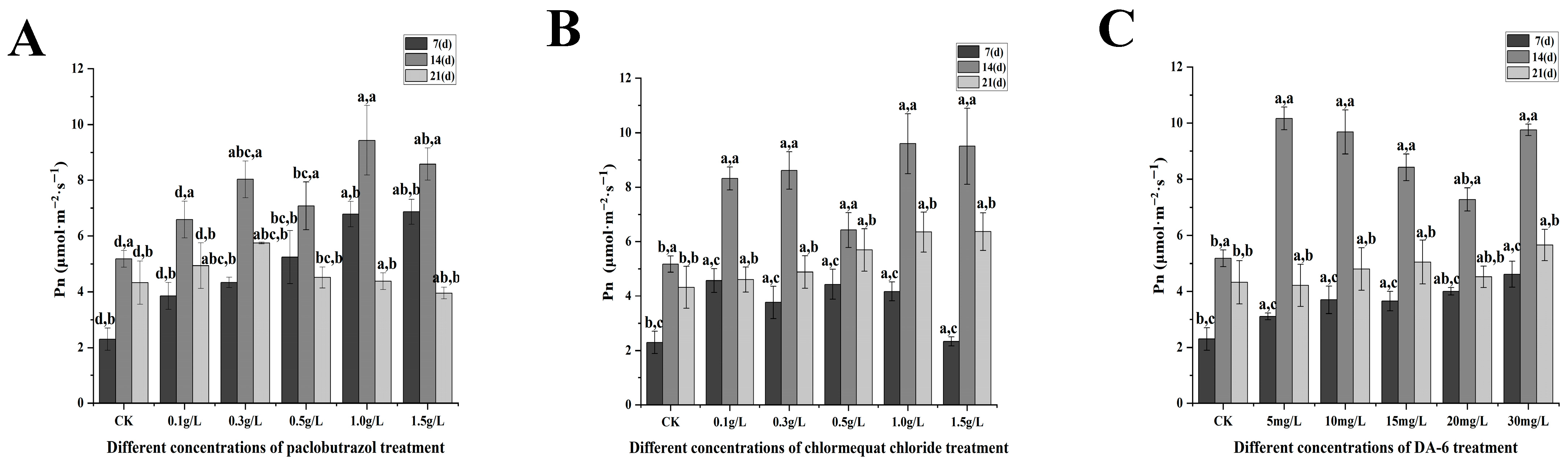

2.3. Photosynthetic Characteristics

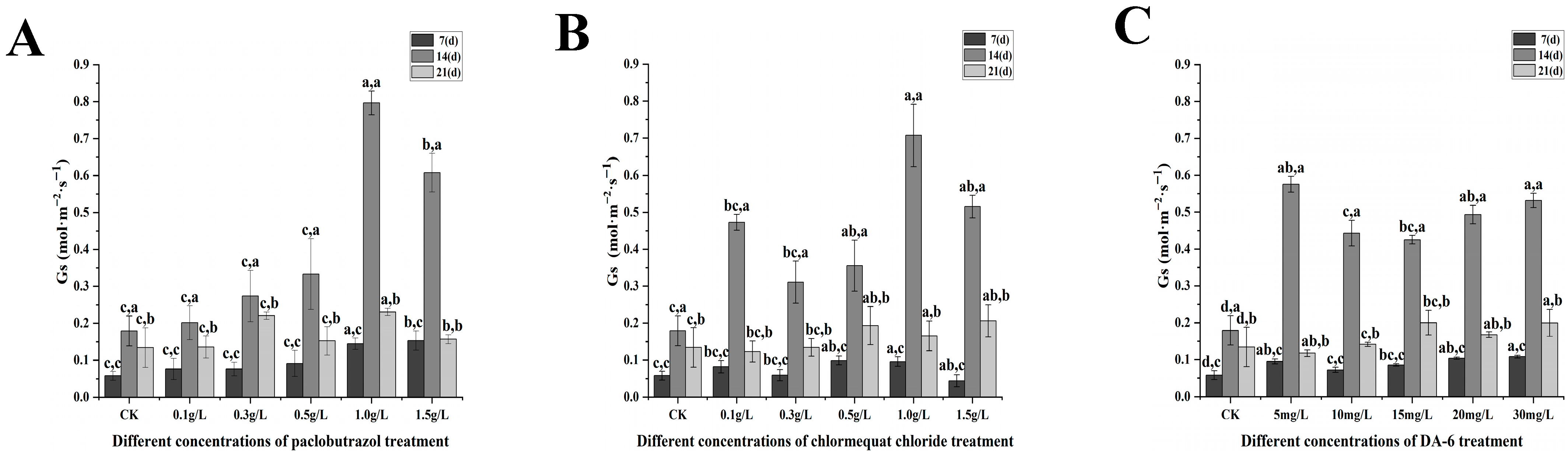

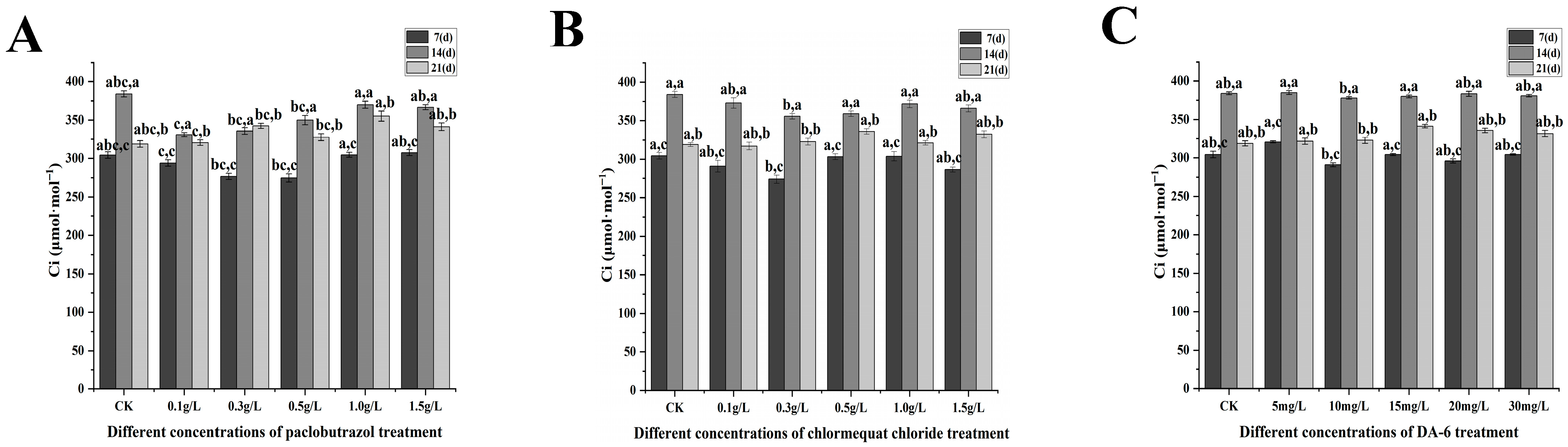

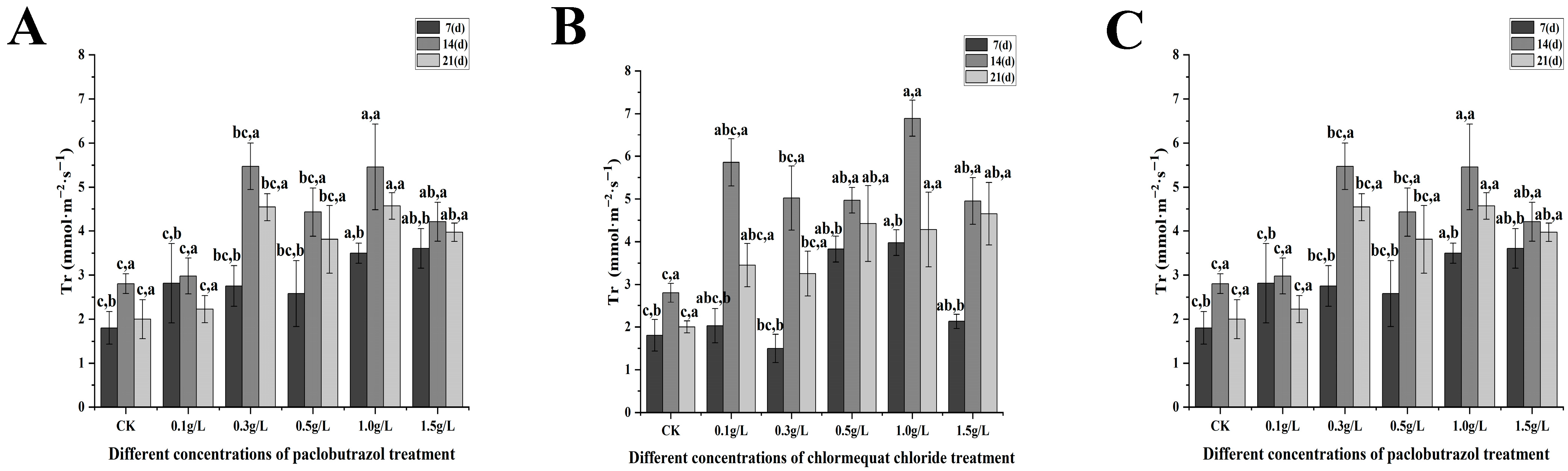

2.3.1. Changes in Photosynthetic Parameters Under Different Paclobutrazol, Chlormequat Chloride and DA-6 Dose Treatments

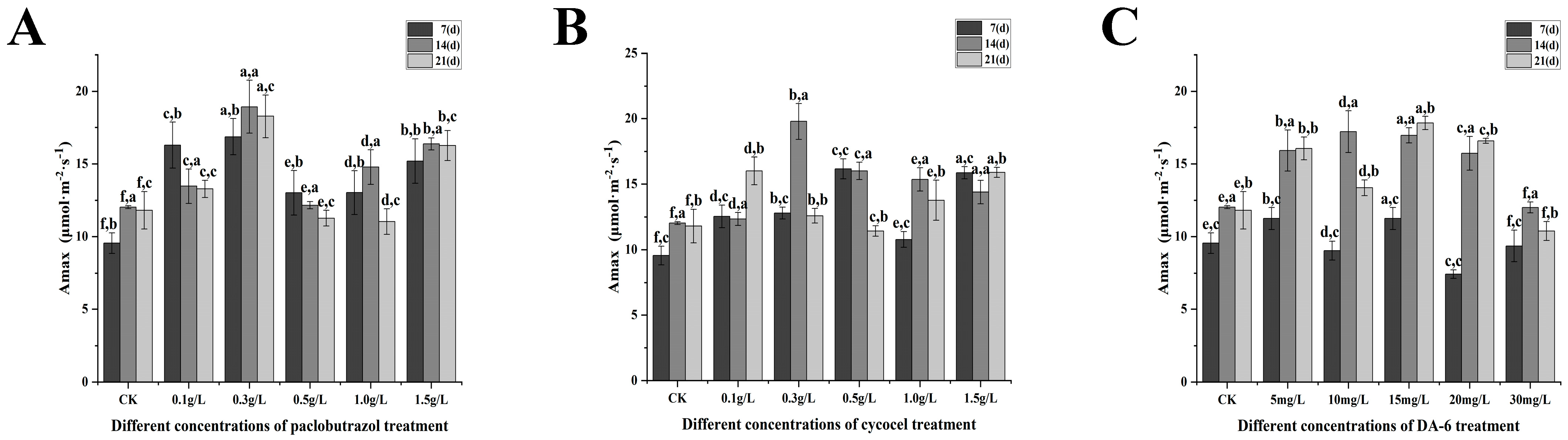

2.3.2. Changes in Maximum Net Photosynthetic Rate Under Different Paclobutrazol, Chlormequat Chloride, and DA-6 Dose Treatments

2.4. Correlation Analysis of Various Indicators Under PGR Treatments

2.4.1. Correlation Analysis Between Growth Indicators and Physiological Indicators

2.4.2. Correlation Analysis Between Growth Indicators and Photosynthetic Indicators

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Area and Materials

4.2. Experimental Design

4.3. Growth Parameter Measurement

4.4. Physiological Index Measurement

4.5. Photosynthetic Parameter Measurement

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Growth Index | Measurement Method | Unit |

| Ground diameter | The stem thickness was measured at 1 cm above the ground surface using a vernier caliper. | cm |

| Crown width | The length was measured from the top of the plant along the east–west direction using a tape measure. | cm |

| Seedling height | The seedling height was measured using a steel ruler, defined as the length from the soil surface to the terminal bud of Pinus koraiensis seedlings. | cm |

| Branch diameter | The branch thickness of the longest lateral branch at 1 cm from the main stem of each Pinus koraiensis seedling was measured using a vernier caliper. | cm |

Appendix A.2

| Physiological Index | Measurement Methods | Unit |

| Chlorophyll | 1. Needles from the middle part of Pinus koraiensis seedlings were collected, and 0.1 g was weighed and cut into approximately 0.2 cm pieces, then placed into a 50 mL centrifuge tube. 2. In the centrifuge tube, 0.5 mL of pure acetone and 10 mL of 80% acetone were added. The needle fragments adhering to the tube wall edges were carefully washed into the acetone solution. The tube was capped and placed in darkness at room temperature for overnight extraction, with shaking 3–4 times during the period. 3. The centrifuge tube was removed the next day. When the leaf tissue had completely turned white, indicating complete chlorophyll extraction, the solution was brought to 25 mL volume with 80% acetone. After centrifugation (25 °C, 3–5 min, 12,000 r·min−1), colorimetric determination was performed. 4. Colorimetric determination: The chloroplast pigment extract was transferred into a cuvette with a 1 cm light path. Absorbance was measured at wavelengths of 645 nm, 663 nm, and 652 nm using a spectrophotometer, with 80% acetone as the blank control. 5. The concentrations of chlorophyll a, b, and total chlorophyll (mg·L−1) were calculated using the following equation: Ca = 12.72 × A663 − 2.59 × A645 (concentration of chlorophyll a) Cb = 22.88 × A663 − 4.67 × A645 (concentration of chlorophyll b) CT = Ca + Cb = 20.29 × A645 + 8.05 × A663 | mg·L−1 |

| Lignin | 1. The main stems of Pinus koraiensis seedlings were collected and rapidly frozen with liquid nitrogen, followed by freeze-drying (overnight). The samples were ground into powder (<20 mesh). 2. The 10–15 mg of sample was weighed and placed into a 20 mL graduated test tube. 10 mL of deionized water was added, and the tube was heated in a 65 °C oven for 1 h with shaking every 10 min. 3. Each sample was filtered through GF/A glass fiber filter paper. The residue was successively rinsed three times each with water, ethanol, acetone, and diethyl ether, 1–2 min per rinse. 4. The filter paper was placed in a 20 mL scintillation vial (uncapped) and heated overnight in a 70 °C oven. 5. A 2.5 mL of 25% bromoacetyl-acetic acid solution was added to each scintillation vial, which was then heated in a 50 °C oven for 2 h (capped) with occasional shaking. 6. A 50 mL volumetric flask was prepared by adding 10 mL of 2 mol/L NaOH solution and 12 mL of glacial acetic acid. 7. After cooling the samples in a refrigerator, they were transferred to the volumetric flask. The filter paper was rinsed with glacial acetic acid, and the volume was brought to 50 mL. The solution was allowed to stand for 1 h. 8. Absorbance at 280 nm was measured. Lignin (mg/g dry weight) = 0.0294 × (ΔA − 0.0068) ÷ (W × T) ΔA: difference in absorbance at 280 nm between the test tube and blank tube W: sample mass (unit: g) T: dilution factor (1 if no dilution) | mg·g−1 |

| Electrical conductivity | 1. 1 g of fresh needles from Pinus koraiensis seedlings was weighed, rinsed with deionized water, cut into pieces, and placed in a 25 mL test tube. 20 mL of deionized water was added, and the tube was allowed to stand at room temperature for 3 h with shaking every half hour. The electrical conductivity of the solution was measured using a DDS-307 electrical conductivity meter, recorded as E1, avoiding contact between the instrument and the beaker wall during measurement. 2. The tube was then placed in a 100 °C water bath and boiled for 15 min, followed by cooling at room temperature. After thorough shaking, the electrical conductivity was measured again using the DDS-307 electrical conductivity meter and recorded as E2. The electrical conductivity of deionized water was measured and recorded as E0. Electrical conductivity (P) = [(E1 − E0)/(E2 − E0)] × 100% | % |

| Bound water to free water ratio | The collected Pinus koraiensis needles were cut into 0.3 cm segments. Three portions of 0.5 g needles each were weighed and placed into three weighing bottles, accurately weighed, then subjected to inactivation at 105 °C for 0.5 h, followed by drying at 80 °C to constant weight to determine tissue water content. Similarly, three additional portions of 0.5 g Pinus koraiensis needles were weighed and placed into three other weighing bottles, accurately weighed. 3 mL of 65% sucrose solution was added to each portion, and the bottles were accurately weighed again to calculate the sugar solution weight. The weighing bottles with added sucrose were placed in the dark for 5 h. After 5 h, the final sugar concentration was determined, along with the original sugar solution concentration. Finally, the free water and bound water contents in the needles were calculated. Equation: Tissue water content = fresh weight − dry weight Freewatercontent = {Sucrose concentration before soaking(%) − Sucrose concentration after soaking (%)} ÷ Sucrose concentration after soaking (%) × Sucrose solution weight (g) × 100% Bound water = tissue water content − free water content | % |

References

- Li, X.; Liu, X.-T.; Wei, J.-T.; Li, Y.; Tigabu, M.; Zhao, X.-Y. Genetic Improvement of Pinus koraiensis in China: Current Situation and Future Prospects. Forests 2020, 11, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Sun, W.; Deng, H.; Xiao, Y. Age Structure of Main Tree Species in Community of Tilia Broadleaf Korean Pine Forest on Northern Slope of Changbai Mountains. Sci. Silvae Sin. 2002, 38, 73–77. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Leon, S.G.; Valenzuela-Soto, E.M. Glycine Betaine is a Phytohormone-Like Plant Growth and Development Regulator Under Stress Conditions. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 42, 5029–5040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafqat, A.; Abbas, S.; Ambreen, M.; Bhatti, A.S.; Kausar, H.; Gull, T. Exploring the Vital Role of Phytohormones and Plant Growth Regulators in Orchestrating Plant Immunity. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2024, 133, 102359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.J.; Qi, H.; Cheng, B.; Hussain, S.; Peng, Y.; Liu, W.; Feng, G.; Zhao, J.; Li, Z. Enhanced Adaptability to Limited Water Supply Regulated by Diethyl Aminoethyl Hexanoate (Da-6) Associated with Lipidomic Reprogramming in Two White Clover Genotypes. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 879331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; He, D.; Yang, S.; Yin, D.; Zhao, H.; Xiao, C. Exogenous Diethylaminoethyl Hexanoate Highly Improved the Cold Tolerance of Early Japonica Rice at Booting. Agronomy 2022, 12, 3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Jiang, Z.; Dong, S. Effects of Da-6 and Mc on the Growth, Physiology, and Yield Characteristics of Soybean. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, K.; Yuan, X.; Zhang, K.; Xue, Y.; Fu, Z.; Lin, P.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Pu, T.; Qi, X.; et al. Diethyl Aminoethyl Hexanoate (Da-6) and Planting Density Optimize Soybean Growth and Yield Formation in Maize–Soybean Strip Intercropping. Crop. J. 2025, 13, 1259–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.-X.; Mou, Y.; Yang, M.-H.; Yu, J.; Tang, D.-Y.; Guo, F.; Gu, Z.; Luo, Z.-L.; Ma, X.-J. [Application and Safety Evaluation of Plant Growth Regulators in Traditional Chinese Medicine]. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 2020, 45, 1824–1832. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattarai, S.; Khanal, N.; Anderson, N.P.; Yoder, C.L. Plant Growth Regulator Effects on Red Fescue Seed Crops in Diverse Production Environments. Crop. Sci. 2024, 64, 3608–3618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, L.; Cao, S.; Li, J.; Yan, J.; Xiong, L.; Wang, F.; He, J. Dwarfing Effect of Plant Growth Retarders on Melaleuca Alternifolia. Forests 2023, 14, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Fan, J.J.; Peng, Q.; Song, W.; Zhou, Y.H.; Xia, C.L.; Ma, J.Z. Effects of Chlormequat Chloride and Paclobutrazol on the Growth and Chlorophyll Fluorescence Kinetics of Daphne Genkwa. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2023, 70, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Ding, W.; Chen, C.; Dai, M.; Chen, X.; Liang, J.; Xu, Y. Effect of Chlormequat Chloride on the Growth and Development of Panax Ginseng Seedlings. HortTechnology 2024, 34, 801–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodeta, K.B.; Ban, S.G.; Perica, S.; Dumicic, G.; Bucan, L. Response of Poinsettia to Drench Application of Growth Regulators. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2010, 8, 297–301. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, J.E. Applying Paclobutrazol at Dormancy Induction Inhibits Shoot Apical Meristem Activity During Terminal Bud Development in Picea Mariana Seedlings. Trees 2017, 31, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yao, R. Optimization of Rhizogenesis for in Vitro Shoot Culture of Pinus Massoniana Lamb. J. For. Res. 2021, 32, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talgø, V.; Stensvand, A.; Pettersson, M.; Fløistad, I.S. Management of Diseases in Norwegian Christmas Tree Plantations. Scand. J. For. Res. 2020, 35, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chorbadjian, R.; Bonello, P.; Herms, D. Effect of the Growth Regulator Paclobutrazol and Fertilization on Defensive Chemistry and Herbivore Resistance of Austrian Pine (Pinus Nigra) and Paper Birch (Betula Papyrifera). Arboric. Urban For. 2011, 37, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Shen, H.; Yang, J.; Wu, L.; Yang, L.; Zhang, P.; Guo, W.; Wang, Y. Effects of Exogenous Flavonoids on Embryogenic Callus Proliferation and Somatic Embryogenesis of Korean Pine. Bull. Bot. Res. 2025, 45, 130–138. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Fang, C.; Krishnan, S.; Chen, J.; Yu, H.; Murphy, A.S.; Merewitz, E.; Katin-Grazzini, L.; McAvoy, R.J.; Deng, Z.; et al. Elevated Auxin and Reduced Cytokinin Contents in Rootstocks Improve Their Performance and Grafting Success. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2017, 15, 1556–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, S.; Wang, M.; Chang, J.; Li, X. Brassinosteroids in Maize: Biosynthesis, Signaling Pathways, and Impacts on Agronomic Traits. Curr. Plant Biol. 2025, 42, 100465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, M.C.; De-La-Cruz-Chacón, I.; Campos, F.G.; Vieira, M.A.R.; Corrêa, P.L.C.; Marques, M.O.M.; Boaro, C.S.F.; Ferreira, G. Plant Growth Regulators Induce Differential Responses on Primary and Specialized Metabolism of Annona Emarginata (Annonaceae). Ind. Crop. Prod. 2022, 189, 115789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chen, Q.; Hou, X. A Study on the Growth and Physiological Traits of Leymus Chinensis in Artificial Grasslands under Exogenous Hormone Regulation. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 30098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, S.; Mohammad, F. Plant Growth Regulators Modulate Photosynthetic Efficiency, Antioxidant System, Root Cell Viability and Nutrient Acquisition to Promote Growth, Yield and Quality of Indian Mustard. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2022, 44, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamloo-Dashtpagerdi, R.; Lindlöf, A.; Aliakbari, M. The Cga1-Snat Regulatory Module Potentially Contributes to Cytokinin-Mediated Melatonin Biosynthesis and Drought Tolerance in Wheat. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutlu, S.; Ilhan, V.; Turkoglu, H.I. Mistletoe (Viscum Album) Infestation in the Scots Pine Stimulates Drought-Dependent Oxidative Damage in Summer. Tree Physiol. 2016, 36, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horemans, N.; Foyer, C.H.; Asard, H. Transport and Action of Ascorbate at the Plant Plasma Membrane. Trends Plant Sci. 2000, 5, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, S.; Pace, R.; Wydrzynski, T. Formation and Decay of Monodehydroascorbate Radicals in Illuminated Thylakoids as Determined by Epr Spectroscopy. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) Bioenerg. 1995, 1229, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Yin, F.; Song, M.; Cai, W.; Shuai, L. Methyl Jasmonate Treatment Alleviates Chilling Injury and Improves Antioxidant System of Okra Pod During Cold Storage. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 2049–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, F.J.D.; Junior, A.P.; Putti, F.F.; Rodrigues, J.D.; Ono, E.O.; Tecchio, M.A.; Leonel, S.; Silva, M.d.S. Effect of Plant Growth Regulators on Germination and Seedling Growth of Passiflora Alata and Passiflora Edulis. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Chen, S.; Jia, Z. The Dwarfing Effects of Different Plant Growth Retardants on Magnolia Wufengensis L.Y. Ma Et L. R. Wang. Forests 2021, 12, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Mu, Y.; Guan, L.; Wu, F.; Liu, K.; Li, M.; Wang, N.; Zhuang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Pwuwrky48 Confers Drought Tolerance in Populus Wulianensis. Forests 2024, 15, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wang, J.; Pan, Y.; Wang, H.; Dang, X.; Zhao, S.; Wang, Y. The Bhlh Transcription Factor Pubhlh66 Improves Salt Tolerance in Daqing Poplar (Populus Ussuriensis). Forests 2024, 15, 2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Wang, M.; Wu, Y.; Hua, Q.; Shen, Y. Study on Desiccation Tolerance and Biochemical Changes of Sassafras Tzumu (Hemsl.) Hemsl. Seeds. Forests 2023, 14, 2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Shen, Y.; Shi, F.; Li, C. Changes in Seed Germination Ability, Lipid Peroxidation and Antioxidant Enzyme Activities of Ginkgo Biloba Seed During Desiccation. Forests 2017, 8, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfim, R.A.A.D.; Cairo, P.A.R.; Barbosa, M.P.; da Silva, L.D.; Sá, M.C.; Almeida, M.F.; de Oliveira, L.S.; Brito, S.d.P.; Gomes, F.P. Effects of Plant Growth Regulators on Mitigating Water Deficit Stress in Young Yellow Passion Fruit Plants. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2024, 46, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.K.A.; Cairo, P.A.R.; Barbosa, R.P.; Lacerda, J.d.J.; Neto, C.d.S.M.; Macedo, T.H.d.J. Physiological Responses of Eucalyptus Urophylla Young Plants Treated with Biostimulant under Water Deficit. Cienc. Florest. 2019, 29, 1072–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, M.; Cordovilla, M.d.P. Plant Growth Regulators Application Enhance Tolerance to Salinity and Benefit the Halophyte Plantago Coronopus in Saline Agriculture. Plants 2021, 10, 1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ying, Y.; Yue, Y.; Huang, X.; Wang, H.; Mei, L.; Yu, W.; Zheng, B.; Wu, J. Salicylic acid induces physiological and biochemical changes in three red bayberry (Myric rubra) genotypes under water stress. Plant Growth Regul. 2013, 71, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Li, S.C.; Yang, Z.R. Effects of Pp333 Soil Application on Growth of Tall Fescue (Festuca Arundinacea Schreb.). Cienc. Florest 2006, 42, 621–624. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; He, P.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Yao, H.; Duan, J.; Hu, S.; Zhou, H.; Li, S. Exogenous diethyl aminoethyl hexanoate, a plant growth regulator, highly improved the salinity tolerance of important medicinal plant Cassia obtusifolia L. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2015, 35, 330–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Wu, Q.; Liu, N.; Zhang, R.; Ma, Z. Phthalanilic Acid with Biostimulatory Functions Affects Photosynthetic and Antioxidant Capacity and Improves Fruit Quality and Yield in Cowpea (Vigna Unguiculata (L.) Walp.). Agriculture 2021, 11, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, H.; Lu, S.; Nai, G.; Ma, W.; Ren, J.; Guo, L.; Chen, B.; Mao, J. The Role of Gibberellin Synthase Gene Vvga2ox7 Acts as a Positive Regulator to Salt Stress in Arabidopsis Thaliana. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.; Sehar, Z.; Fatma, M.; Mir, I.R.; Iqbal, N.; Tarighat, M.A.; Abdi, G.; Khan, N.A. Involvement of Ethylene in Melatonin-Modified Photosynthetic-N Use Efficiency and Antioxidant Activity to Improve Photosynthesis of Salt Grown Wheat. Physiol. Plant. 2022, 174, e13832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.W.; Juvik, J.A.; Spomer, L.A.; Fermanian, T.W. Growth Retardant Effects on Visual Quality and Nonstructural Carbohydrates of Creeping Bentgrass. HortScience 1998, 33, 1197–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidlova, L.; Verlinden, M.; Gloser, J.; Milbau, A.; Nijs, I. Which Plant Traits Promote Growth in the Low-Light Regimes of Vegetation Gaps? Plant Ecol. 2009, 200, 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenkanen, A.; Suprun, S.; Oksanen, E.; Keinänen, M.; Keski-Saari, S.; Kontunen-Soppela, S. Strategy by Latitude? Higher Photosynthetic Capacity and Root Mass Fraction in Northern Than Southern Silver Birch (Betula Pendula Roth) in Uniform Growing Conditions. Tree Physiol. 2021, 41, 974–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Nie, J.; Yao, X.; Guo, Y.; Ahmad, M.; Shah, S.A.A.; Hayat, F.; Niamat, Y.; Öztürk, H.I.; Sui, X. Influence of Nitrate Levels on Plant Growth and Carbon and Nitrogen Metabolism in Cucumber (Cucumis Sativus L.) under Low Light Stress. Turk Tarim Ve Orman. Derg. Turk. J. Agric. For. 2024, 48, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.; Guo, H.; Yan, L.-P.; Gao, L.; Zhai, S.; Xu, Y. Physiological, Photosynthetic and Stomatal Ultrastructural Responses of Quercus Acutissima Seedlings to Drought Stress and Rewatering. Forests 2024, 15, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mthiyane, P.; Aycan, M.; Mitsui, T. Integrating Biofertilizers with Organic Fertilizers Enhances Photosynthetic Efficiency and Upregulates Chlorophyll-Related Gene Expression in Rice. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Chiu, L.-W.; Hoyle, J.W.; Dewhirst, R.A.; Richey, C.; Rasmussen, K.; Du, J.; Mellor, P.; Kuiper, J.; Tucker, D.; et al. Enhanced Photosynthetic Efficiency for Increased Carbon Assimilation and Woody Biomass Production in Engineered Hybrid Poplar. Forests 2023, 14, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Tang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zang, Y.; Zhou, B. A Zostera Marina Manganese Superoxide Dismutase Gene Involved in the Responses to Temperature Stress. Gene 2016, 575 Pt 3, 718–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Didi, D.A.; Su, S.; Sam, F.E.; Tiika, R.J.; Zhang, X. Effect of Plant Growth Regulators on Osmotic Regulatory Substances and Antioxidant Enzyme Activity of Nitraria Tangutorum. Plants 2022, 11, 2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scagel, C.F.; Linderman, R.G. Modification of Root Iaa Concentrations, Tree Growth, and Survival by Application of Plant Growth Regulating Substances to Container-Grown Conifers. New For. 2001, 21, 159–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullman, G.S.; Zhang, Y.; Phan, B.H. Brassinolide Improves Embryogenic Tissue Initiation in Conifers and Rice. Plant Cell Rep. 2003, 22, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, J.A.; Matsumoto, S.N.; Trazzi, P.A.; Ramos, P.A.S.; de Oliveira, L.S.; Campoe, O.C. Morphophysiological Changes by Mepiquat Chloride Application in Eucalyptus Clones. Trees 2021, 35, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litwińczuk, W.; Jacek, B. Growth of Paulownia Ssp. Interspecific Hybrid ‘Oxytree’ Micropropagated Nursery Plants under the Influence of Plant-Growth Regulators. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, M.; Poor, P.; Kaur, H.; Aher, R.R.; Palakolanu, S.R.; Khan, M.I.R. Salt Stress Tolerance and Abscisic Acid in Plants: Associating Role of Plant Growth Regulators and Transcription Factors. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 228, 110303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Y.; Han, Z. Abscisic Acid, Paclobutrazol, and Salicylic Acid Alleviate Salt Stress in Populus Talassica × Populus Euphratica by Modulating Plant Root Architecture, Photosynthesis, and the Antioxidant Defense System. Forests 2022, 13, 1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Shen, W.; Guo, J.; Wang, C.; Zhao, Z. Regulating Growth of Betula Alnoides Buch. Ham. Ex D. Don Seedlings with Combined Application of Paclobutrazol and Gibberellin. Forests 2019, 10, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žiauka, J.; Striganavičiūtė, G.; Szyp-Borowska, I.; Kuusienė, S.; Niemczyk, M. Differences in Environmental and Hormonal Regulation of Growth Responses in Two Highly Productive Hybrid Populus Genotypes. Forests 2022, 13, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cregg, B.; Ellison-Smith, D.; Rouse, R. Managing Cone Formation and Leader Growth in Fraser Fir Christmas Tree Plantations with Plant Growth Regulators. Forests 2022, 14, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, S.; Farooqi, A.H.A.; Gupta, M.M.; Sangwan, R.S.; Khan, A. Effect of Ethrel, Chlormequat Chloride and Paclobutrazol on Growth and Pyrethrins Accumulation in Chrysanthemum Cinerariaefolium Vis. Plant Growth Regul. 2007, 51, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Gao, J.; Sun, J.; Pan, Z.; Liu, F.; Deng, X.; Han, W.; Yang, H.; Wang, B.; Wang, W. Effects of Chemical Regulation on the Growth, Yield and Fiber Quality of Cotton Varieties with Different Plant Architectures. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj-Napoca 2024, 52, 13393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Q.N.; Wang, A.A.; Long, Z.F.; Chen, H.F.; Dan, Z.H.; Chen, S.L.; Deng, J.B.; Zhou, X.A. Effects of Da-6 on the Characteristics, Yield and Quality of Soybean Varieties in South China. Soybean Sci. 2021, 40, 799–804. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, S.; Zhou, X.; Cui, X.; Liu, C.; Fan, Y.; McBride, M.B.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhuang, P. Exogenous Plant Growth Regulators Improved Phytoextraction Efficiency by Amaranths Hypochondriacus L. In Cadmium Contaminated Soil. Plant Growth Regul. 2020, 90, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, K.; Xie, C.; Wang, J.; Du, Q.; Cheng, P.; Wang, T.; Wu, Y.; Yang, W.; Yong, T. Uniconazole, 6-Benzyladenine, and Diethyl Aminoethyl Hexanoate Increase the Yield of Soybean by Improving the Photosynthetic Efficiency and Increasing Grain Filling in Maize–Soybean Relay Strip Intercropping System. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2021, 40, 1869–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.J.; Geng, W.; Zeng, W.; Raza, M.A.; Khan, I.; Iqbal, M.Z.; Peng, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Li, Z. Diethyl Aminoethyl Hexanoate Priming Ameliorates Seed Germination Via Involvement in Hormonal Changes, Osmotic Adjustment, and Dehydrins Accumulation in White Clover under Drought Stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 709187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, A.G.; Wu, X.; Kabra, A.N.; Kim, D.-P. Cultivation of an Indigenous Chlorella Sorokiniana with Phytohormones for Biomass and Lipid Production under N-Limitation. Algal Res. 2017, 23, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Huang, X.; Li, Z.; Li, M.; Wang, N.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Sun, T.; Wang, H. Effects of Chlormequat Chloride Treatment on the Growth and Physiological Indices of Wheat. Cereal Res. Commun. 2025, 53, 1147–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, S.; An, Y.; Peng, F.; Xiong, J.; Molidaxing, A.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, B. A Comparative Analysis of the Efficacy of Three Plant Growth Regulators and Dose Optimization for Improving Agronomic Traits and Seed Yield of Purple-Flowered Alfalfa (Medicago Sativa L.). Plants 2025, 14, 2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, R.; Gu, W.; Zhang, J.; Hao, L.; Zhang, M.; Duan, L.; Li, Z. Exogenous Diethyl Aminoethyl Hexanoate Enhanced Growth of Corn and Soybean Seedlings through Altered Photosynthesis and Phytohormone. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 2013, 7, 2021–2028. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Hao, W. Reproductive and Developmental Toxicity of Plant Growth Regulators in Humans and Animals. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2023, 196, 105640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiss, C.; Cummings, B. Experiments in Plant Physiology. Experiment 1994, 12, 1619–1624. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, D.; Gao, S.; Gao, H.; Qiu, N. The Details of Protein Content Determination by Coomassie Brilliant Blue Staining. Exp. Sci. Technol. 2018, 16, 143–147. [Google Scholar]

- Klukas, C.; Chen, D.; Pape, J.M. Integrated Analysis Platform: An Open-Source Information System for High-Throughput Plant Phenotyping. Plant Physiol. 2014, 165, 506–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arditti, J. Experimental Plant Physiology: Experiments in Cellular and Plant Physiology. Osterreichische Krankenpflegezeitschrift 1969, 37, 235–237. [Google Scholar]

- Villegas-Velázquez, I.; Zavaleta-Mancera, H.; Arévalo-Galarza, M.; Suarez-Espinosa, J.; Garcia-Osorio, C.; Padilla-Chacon, D.; Galvan-Escobedo, I.; Jimenez-Bremont, J. Chlorophyll Measurements in Alstroemeria Sp. Using Spad-502 Meter and the Color Space Cie L*a*B*, and Its Validation in Foliar Senescence. Photosynthetica 2022, 60, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Fu, J.; Meng, C.; Dai, L.; Baek, N.-W.; Gao, W.; Fan, X. Determination of the Lignin Content of Flax Fiber with the Acetyl Bromide-Ultraviolet Visible Spectrophotometry Method. Text. Res. J. 2023, 93, 2633–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuhata, M. Electrical Conductivity Measurement of Electrolyte Solution. Electrochemistry 2022, 90, 102011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malyshev, R.V. Definitions of Free and Bound Water in Plants and a Comparative Analysis of the Drying Method over a Dewatering Agent and Differential Scanning Calorimetry. Biol. Bull. Rev. 2021, 11, 640–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Lv, Y.; Liu, X.; Wei, Q.; Qi, Z.; Yang, S.; Liao, L. A General Non-Rectangular Hyperbola Equation for Photosynthetic Light Response Curve of Rice at Various Leaf Ages. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 9909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, W.; Li, C.; Li, Z.; Hu, N.; Cao, G.; Huang, J.; Yang, P.; Liu, H.; Bai, H.; Zhang, H. Effects of Different Plant Growth Regulators on Growth Physiology and Photosynthetic Characteristics of Pinus koraiensis Seedlings. Plants 2025, 14, 3671. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233671

Zhang W, Li C, Li Z, Hu N, Cao G, Huang J, Yang P, Liu H, Bai H, Zhang H. Effects of Different Plant Growth Regulators on Growth Physiology and Photosynthetic Characteristics of Pinus koraiensis Seedlings. Plants. 2025; 14(23):3671. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233671

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Wenbo, Chunming Li, Zhenghua Li, Naizhong Hu, Guanghao Cao, Jiaqi Huang, Panke Yang, Huanzhen Liu, Hui Bai, and Haifeng Zhang. 2025. "Effects of Different Plant Growth Regulators on Growth Physiology and Photosynthetic Characteristics of Pinus koraiensis Seedlings" Plants 14, no. 23: 3671. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233671

APA StyleZhang, W., Li, C., Li, Z., Hu, N., Cao, G., Huang, J., Yang, P., Liu, H., Bai, H., & Zhang, H. (2025). Effects of Different Plant Growth Regulators on Growth Physiology and Photosynthetic Characteristics of Pinus koraiensis Seedlings. Plants, 14(23), 3671. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233671